Nisse (folklore)

A nisse (Danish: [ˈne̝sə], Norwegian: [ˈnɪ̂sːə]), tomte (Swedish: [ˈtɔ̂mːtɛ]), tomtenisse, or tonttu (Finnish: [ˈtontːu]) is a mythological creature from Nordic folklore today typically associated with the winter solstice and the Christmas season. They are generally described as being short, having a long white beard, and wearing a conical or knit cap in gray, red or some other bright colour. They often have an appearance somewhat similar to that of a garden gnome.

The nisse is one of the most familiar creatures of Scandinavian folklore, and he has appeared in many works of Scandinavian literature. With the romanticisation and collection of folklore during the 19th century, the nisse gained popularity.

Terminology

The word nisse is a pan-Scandinavian term.[3] Its current use in Norway into the 19th century is evidenced in Asbjørnsen's collection.[1][2] The Norwegian tufte is also equated to nisse or tomte.[4][5]

English translations

While the term nisse in the native Norwegian is retained in Pat Shaw Iversen's English translation (1960), appended with the parenthetical remark that it is a household spirit,[6] H. L. Braekstad (1881) chose to substitute nisse with "brownie".[1][2] Brynildsen's dictionary (1927) glossed nisse as 'goblin' or 'hobgoblin'.[7]

In the English editions of the Hans Christian Andersen's fairy tales the Danish word nisse has been translated as 'goblin', for example, in the tale "The Goblin at the Grocer's".[8]

Dialects

Forms such as tufte have been seen as dialect. Aasen noted the variant form tuftekall to be prevalent in the Nordland and Trondheim areas of Norway,[4] and the tale "Tuftefolket på Sandflesa" published by Asbjørnsen is localized in Træna in Nordland.[a] Another synonym is tunkall ("yard fellow"[10]) also found in the north and west.[11]

Thus ostensibly tomte prevails in eastern Norway (and adjoining Sweden),[12][13] although there are caveats attached to such over-generalizations by linguist Oddrun Grønvik.[13][14][b] It might also be conceded that tomte is more a Swedish term than Norwegian.[15] In Scania, Halland and Blekinge the Nisse also known as goanisse (Godnisse, Goenisse≈the good Nisse).[16]

Reidar Thoralf Christiansen remarked that the "belief in the nisse is confined to the south and east" of Norway,[11] and theorized the nisse was introduced to Norway (from Denmark) in the 17th century, but there is already mention of "Nisse pugen" in a Norwegian legal tract c. 1600 or earlier, and Emil Birkeli (1938) believed the introduction to be as early as 13 to 14c.[17] The Norsk Allkunnebok encyclopedia was of the view that nisse was introduced from Denmark relatively late, and that native names found in Norway such as tomte, tomtegubbe, tufte, tuftekall, gardvord, etc., date much older.[3][18]

Etymology

The term nisse may be derived from Old Norse niðsi, meaning "dear little relative".[19] Another explanation is that it is a corruption of Nils, the Scandinavian form of Nicholas.[10][3] A conjecture has also been advanced that nisse might be related to the "nixie",[20][21] but this is a water sprite and the proper cognate is the nøkk, not the nisse.[22]

The tomte ("homestead man"), gardvord ("farm guardian"), and tunkall ("yard fellow") bear names that associated them with the farmstead.[10] The Finnish tonttu is also derived from the term for a place of residence and area of influence: the house lot, tontti (Finnish).[citation needed]

Additional synonyms

Norwegian gardvord is a synonym for nisse,[21][23][c] or has become conflated with it.[25] Likewise turvord is a synonym.[21]

- Near synonyms

According to Oddrun Grønvik, the nisse has a distinct connotation and is not synonymous with the haugkall or haugebonde (from the Old Norse haugr 'mound'), although the latter has become indistinguishable with tuss, as evident from the form haugtuss.[26][d]

History and cultural relevance

According to tradition, the nisse lives in the houses and barns of the farmstead, and secretly acts as their guardian.[28] If treated well, they protect the family and animals from evil and misfortune,[29] and may also aid the chores and farm work.[30] However, they are known to be short tempered, especially when offended. Once insulted, they will usually play tricks, steal items and even maim or kill livestock.[31]

Appearance

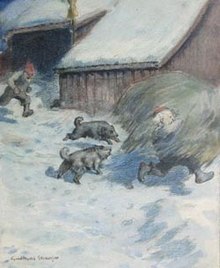

The nisse/tomte was often imagined as a small, elderly man (size varies from a few inches to about half the height of an adult man), often with a full beard; dressed in the traditional farmer garb, consisting of a pull-over woolen tunic belted at the waist and knee breeches with stockings. This was still the common male dress in rural Scandinavia in the 17th century, giving an indication of when the idea of the nisse spread. However, there are also folktales where he is believed to be a shapeshifter able to take a shape far larger than an adult man, and other tales where the nisse is believed to have a single, Cyclopean eye. In modern Denmark, nisser are often seen as beardless, wearing grey and red woolens with a red cap. Since nisser are thought to be skilled in illusions and sometimes able to make themselves invisible, one was unlikely to get more than brief glimpses of him no matter what he looked like. Norwegian folklore states that he has four fingers, and sometimes with pointed ears and eyes reflecting light in the dark, like those of a cat. [32]

Height

The Tomte's height is anywhere from 60 cm (2 ft) to no taller than 90 cm (3 ft) according to one Swedish-American source,[33] whereas the tomte (pl. tomtarna) were just 1 aln tall (an aln or Swedish ell being just shy of 60 cm or 2 ft), according to one local Swedish tradition.[e][34]

Temperament

This section needs additional citations for verification. (March 2024) |

Despite his small size, nisse possess immense strength.[35] They are easily offended by carelessness, lack of proper respect, and lazy farmers.[36] As the protector of the farm and caretaker of livestock, their retributions for bad practices range from small pranks like a hard strike to the ear to more severe punishment like killing of livestock or ruining of the farm's fortune. Observance of traditions is thought to be important to the nisse, as they do not like changes in the way things are done at their farms. They are also easily offended by rudeness; farm workers swearing, urinating in the barns, or not treating the creatures well can frequently lead to a sound thrashing by the tomte/nisse. If anyone spills something on the floor in the nisse's house, it is considered proper to shout a warning to the tomte below.

One is also expected to please nisse with gifts (see Blót) – a traditional gift is a bowl of porridge on Christmas Eve. If the tomte is not given his gift, he might leave the farm or house or engage in mischief such as tying the cows' tails together in the barn, turning objects upside-down, and breaking things (like a troll). The nisse likes his porridge with a pat of butter on the top. In an often retold story,[37] a farmer put the butter underneath the porridge. When the nisse of his farmstead found that the butter was missing, he was filled with rage and killed the cow resting in the barn. But, as he thus became hungry, he went back to his porridge (ricepudding) and ate it, and so found the butter at the bottom of the bowl. Full of grief, he then hurried to search the lands to find another farmer with an identical cow, and replaced the former with the latter. In another tale a Norwegian maid decided to eat the porridge herself, and ended up severely beaten by the nisse. The being swore: "Have you eaten the porridge for the nisse, you have to dance with him!". The farmer found her nearly lifeless the morning after.

The nisse is connected to farm animals in general, but his most treasured animal is the horse.[35] Belief has it that one could see which horse was the tomte's favourite as it will be especially healthy and well taken care of. Sometimes the tomte will even braid its hair and tail. Undoing these braids without permission can mean misfortune or angering the tomte. Some stories tell how the nisse could drive people mad or bite them. The bite from a nisse is poisonous, and otherworldly healing is usually required. As the story goes, a girl who was bitten withered and died before help arrived.

An angry tomte is featured in the popular children's book by Swedish author Selma Lagerlöf, Nils Holgerssons underbara resa genom Sverige (The Wonderful Adventures of Nils). The tomte turns the naughty boy Nils into a pixie in the beginning of the book, and Nils then travels across Sweden on the back of a goose.

After Christianization

The nisse or tomte was in ancient times believed to be the "soul" of the first inhabitant of the farm; he who cleared the tomt (house lot). He had his dwellings in the burial mounds on the farm, hence the now somewhat archaic Swedish names tomtenisse and tomtekarl, the Swedish and Norwegian tomtegubbe and tomtebonde ("tomte farmer"), Danish husnisse ("house nisse"), the Norwegian haugkall ("mound man"), and the Finnish tonttu-ukko (lit. "house lot man").

The nisse was not always a popular figure, particularly during and after the Christianization of Scandinavia. Like most creatures of folklore he would be seen as heathen (pre-Christian) and be demonized and connected to the Devil. Farmers believing in the house tomte could be seen as worshiping false gods or demons; in a famous 14th-century decree, Saint Birgitta warns against the worship of tompta gudhi,[37] "tomte gods" (Revelationes, book VI, ch. 78). Folklore added other negative beliefs about the tomte, such as that having a tomte on the farm meant you put the fate of your soul at risk, or that you had to perform various non-Christian rites to lure a tomte to your farm.

The belief in a nisse's tendency to bring riches to the farm by his unseen work could also be dragged into the conflicts between neighbors. If one farmer was doing far better for himself than the others, someone might say that it was because he had a nisse on the farm, doing "ungodly" work and stealing from the neighbors. These rumors could be very damaging for the farmer who found himself accused, much like accusations of witchcraft during the Inquisitions.

Similar folklore

The nisse shares many aspects with other Scandinavian wights such as the Swedish vättar (from the Old Norse vættr), Danish vætter, Norwegian vetter or tusser. These beings are social, however, whereas the nisse is always solitary (though he is now often pictured with other nisser). Often comparable to the Latin American "Duende". Synonyms of nisse includes gårdbo ("(farm)yard-dweller"), gardvord ("yard-warden", see vörðr) in all Scandinavian languages, and god bonde ("good farmer"), gårdsrå ("yard-spirit") in Swedish and Norwegian and fjøsnisse ("barn gnome") in Norwegian. The tomte could also take a ship for his home, and was then known as a skeppstomte or skibsnisse. In Finland, the sauna has a saunatonttu. Also related is the Nis Puk,[38] which is widespread in the area of Southern Jutland/Schleswig, in the Danish-German border area.

In other European folklore, there are many beings similar to the nisse, such as the Scots and English brownie, Northumbrian English hob, West Country pixie, the German Heinzelmännchen, the Dutch kabouter or the Slavic domovoi. Usage in folklore in expressions such as Nisse god dräng ("Nisse good lad") is suggestive of Robin Goodfellow.[39]

Modern Nisse

This section may require cleanup to meet Wikipedia's quality standards. The specific problem is: Doesn't fully account for the "santa clausification" of the nordic countries - see talk. (December 2016) |

The tradition of nisse/tomte is also associated with Christmas (Swedish: Jultomten, Template:Lang-da, Norwegian: Julenissen or Finnish: Joulutonttu.[40]) The tomte is accompanied by another mythological creature: the Yule goat (Julbocken). The pair appear on Christmas Eve, knocking on the doors of people's homes, handing out presents.[41]

The nisse will deliver gifts at the door, in accordance with the modern-day tradition of the visiting Santa Claus, enters homes to hand out presents.[42] The tomte/nisse is also commonly seen with a pig, another popular Christmas symbol in Scandinavia, probably related to fertility and their role as guardians of the farmstead. It is customary to leave behind a bowl of porridge with butter for the tomte/nisse, in gratitude for the services rendered.[43]

In the 1840s the farm's nisse became the bearer of Christmas presents in Denmark, and was then called julenisse (Yule Nisse). In 1881, the Swedish magazine Ny Illustrerad Tidning published Viktor Rydberg's poem "Tomten", where the tomte is alone awake in the cold Christmas night, pondering the mysteries of life and death. This poem featured the first painting by Jenny Nyström of this traditional Swedish mythical character which she turned into the white-bearded, red-capped friendly figure associated with Christmas ever since. Shortly afterwards, and obviously influenced by the emerging Father Christmas traditions as well as the new Danish tradition, a variant of the nisse/tomte, called the jultomte in Sweden and julenisse in Norway, started bringing the Christmas presents in Sweden and Norway, instead of the traditional julbock (Yule Goat).

Gradually, commercialism has made him look more and more like the American Santa Claus, but the Swedish jultomte, the Norwegian julenisse, the Danish julemand and the Finnish joulupukki (in Finland he is still called the Yule Goat, although his animal features have disappeared) still has features and traditions that are rooted in the local culture. He doesn't live on the North Pole, but perhaps in a forest nearby, or in Denmark he lives on Greenland, and in Finland he lives in Lapland; he doesn't come down the chimney at night, but through the front door, delivering the presents directly to the children, just like the Yule Goat did; he is not overweight; and even if he nowadays sometimes rides in a sleigh drawn by reindeer, instead of just walking around with his sack, his reindeer don't fly—and in Sweden, Denmark and Norway some still put out a bowl of porridge for him on Christmas Eve. He is still often pictured on Christmas cards and house and garden decorations as the little man of Jenny Nyström's imagination, often with a horse or cat, or riding on a goat or in a sled pulled by a goat, and for many people the idea of the farm tomte still lives on, if only in the imagination and literature.

The use of the word tomte in Swedish is now somewhat ambiguous, but often when one speaks of jultomten (definite article) or tomten (definite article) one is referring to the more modern version, while if one speaks of tomtar (plural) or tomtarna (plural, definite article) one could also likely be referring to the more traditional tomtar. The traditional word tomte lives on in an idiom, referring to the human caretaker of a property (hustomten), as well as referring to someone in one's building who mysteriously does someone a favour, such as hanging up one's laundry. A person might also wish for a little hustomte to tidy up for them. A tomte stars in one of author Jan Brett's children's stories, Hedgie's Surprise.[44] When adapting the mainly English-language concept of tomten having helpers (sometimes in a workshop), tomtenisse can also correspond to the Christmas elf, either replacing it completely, or simply lending its name to the elf-like depictions in the case of translations.

Nisser/tomte often appear in Christmas calendar TV series and other modern fiction. In some versions the tomte are portrayed as very small; in others they are human-sized. The nisse usually exist hidden from humans and are often able to use magic.

The 2018 animated series Hilda, as well as the graphic novel series it is based on, features nisse as a species. One nisse named Tontu is a recurring character, portrayed as a small, hairy humanoid who lives unseen in the main character's home.

Garden gnome

The appearance traditionally ascribed to a nisse or tomte resembles that of the garden gnome figurine for outdoors, which are in turn, also called trädgårdstomte in Swedish, havenisse in Danish, hagenisse in Norwegian and puutarhatonttu in Finnish.[citation needed]

See also

- Brownie (Scotland and England)

- Domovoi (Slavic)

- Duende (Spain, Hispanic America)

- Dwarf

- Elf

- Christmas elf

- Gnome

- Heinzelmännchen (Germany)

- Kabouter (The Netherlands)

- Hob (Northern England)

- Household deity

- Kobold (Germany)

- Legendary creature

- Leprechaun (Ireland)

- Nis Puk (in Schleswig/Southern Jutland, now divided between Denmark (Northern Schleswig) and Germany (Southern Schleswig)

- Santa Claus

- Sprite

- Spiriduș (Romania)

- Tonttu or Haltija (Finland)

- Tudigong

- Vættir

- Yule Lads (Iceland)

Explanatory notes

- ^ The tale "Tuftefolket på Sandflesa" describes its setting as Trena, and Sandflesa is explained as a shifting bank off its shore.[9]

- ^ Ottar Grønvik specifically addresses the generalization "tufte (-kall) har utbreeinga si noko nord- og vestafor tomte (-gubbe)," i.e., tufte(-kall) being in use to the north and west of regions where tomte(-gubbe) is prevalent, and states there is too scanty a material ("lite tilfang") to build on. Ottar Grønvik's 1997 study argues that in general, current literature "does not give an accurate picture of their distribution [i.e., of the geographical distribution of the usage of varying terms for nisse] in the 19th century".[14]

- ^ Or synonymous with tunkall, as Christiansen comments,[24] but this concerns the tale "The Gardvord Beats up the Troll" collected by Ivar Aasen, and Aasen's dictionary glosses gardvord as 'nisse, vætte', as a thing believed to reside on the farm (Template:Lang-da).[23]

- ^ Contrary to some commentators such as the writer Tor Åge Bringsværd who includes tusse among the synonyms for nisse.[27]

- ^ While a gaste was 2 alnar tall.[34]

References

Citations

- ^ a b c Asbjørnsen (1896) [1879]. "En gammeldags juleaften", pp. 1–19; Braekstad (1881) tr. "An Old-Fashioned Christmas Eve". pp. 1–18.

- ^ a b c Asbjørnsen (1896) [1879]. "En aftenstund i et proprietærkjøkken", pp. 263–284; Braekstad (1881) tr. "An Evening in the Squire's Kitchen". pp. 248–268.

- ^ a b c Sudman, Arnulv, ed. (1948). "Nisse". Norsk allkunnebok. Vol. 8. Oslo: Fonna forlag. p. 232.

- ^ a b Aasen (1873) Norsk ordbog s.v. "Tufte". 'vætte, nisse, unseen neighbor, in the majority ellefolk (elf-folk) or underjordiske (underground folk) but also (regionally) in the Nordland and Trondheim tuftefolk'.

- ^ Brynildsen (1927) Norsk-engelsk ordbok s.v. "tuftekall", see tunkall; tuften, see Tomten.

- ^ Christiansen (2016), p. 137.

- ^ Brynildsen (1927) Norsk-engelsk ordbok s.v. "2nisse", '(hob)goblin'.

- ^ Binding (2014). Chapter 9, §6 and endnote 95.

- ^ Christiansen (2016) [1960]. "The Tufte-Folk on Sandflesa". pp. 61–66.

- ^ a b c Kvideland & Sehmsdorf (1988), p. 238.

- ^ a b Christiansen (2016), pp. 141, lc.

- ^ Stokker (2000), p. 54.

- ^ a b Grønvik, Ottar (1997), p. 154.

- ^ a b "9810010 Grønvik, Oddrun.. Ordet nisset, etc.", Linguistics and Language Behavior Abstracts, 32 (4): 2058, 1998,

it is argued that the current material does not give an accurate picture of their distribution in the 19th century.

- ^ Knutsen & Riisøy (2007), p. 48 and note 28.

- ^ Axel Olrik and Hans Ellekilde: Nordens gudeverden, p. 294

- ^ Knutsen & Riisøy (2007), p. 51 and note 35.

- ^ Also quoted in Grønvik, Ottar (1997), p. 130

- ^ Grønvik, Ottar (1997), pp. 129, 144–145:"Norwegian: den lille/kjære slektningen".

- ^ Sayers, William (1997). "The Irish Bóand-Nechtan Myth in the Light of Scandinavian Evidence" (PDF). Scandinavian-Canadian Studies. 2: 66.

- ^ a b c Falk & Torp (1906) s. v. "[https://books.google.com/books?id=-SMRAQAAMAAJ&pg=PA13 nisse".

- ^ Binding (2014). endnote 23 to Chapter 4,. Citing Briggs, Katherine (1976). A Dictionary of Fairies.

- ^ a b Aasen (1873) Norsk ordbog s.v. "gardvord".

- ^ Christiansen (2016), p. 143.

- ^ Bringsværd (1970), p. 89.

- ^ Grønvik, Oddrun (1997), p. 154.

- ^ Bringsværd (1970), p. 89. "the nisse, also known under the name of tusse, tuftebonde, tuftekall, tomte and gobonde".

- ^ German and Scandinavian Legendary Creatures Retrieved 2 December 2013

- ^ Keeping Swedish culture alive with St. Lucia Day, Tomte Archived 2013-12-03 at the Wayback Machine Retrieved 2 December 2013

- ^ Tomte: Scandinavian Christmas traditions at the American Swedish Institute Retrieved 2 December 2013

- ^ Friedman, Amy. Go San Angelo: Standard-Times. "Tell Me a story: The Tomte's New Suit (A Swedish Tale) Archived 2013-12-03 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved 2 December 2013.

- ^ "Legend of the Nisse and Tomte". Ingebretsen's. Archived from the original on June 5, 2019. Retrieved June 1, 2019.

- ^ "Made in Sweden: Four Delightful Christmas Products". Sweden & America. Swedish Council of America: 49. Autumn 1995.

- ^ a b Arill, David (Autumn 1924). "Tomten och gasten (Frändefors)". Tro, sed och sägen: folkminnen (in Swedish). Wettergren & Kerber. p. 45.

- ^ a b Lillejord, S; Mkabela, N (2004). "Indigenous and popular narratives: The educational use of myths in a comparative perspective". South African Journal of Higher Education. 18 (3): 257–268 – via Unisa Press.

- ^ Rue, Anna (2018). ""It Breathes Norwegian Life": Heritage Making at Vesterheim Norwegian-American Museum". Scandinavian Studies. 90 (3): 350–375. doi:10.5406/scanstud.90.3.0350. ISSN 0036-5637. JSTOR 10.5406/scanstud.90.3.0350.

- ^ a b "The Swedish Tomte – Swedish Press". 2018-12-22. Retrieved 2024-03-16.

- ^ e. g. Hans Rasmussen: Sønderjyske sagn og gamle fortællinger, 2019, ISBN 978-8-72-602272-8

- ^ "Rühs, Fredrik (Friedrich Rühs)". Biographiskt Lexicon öfver namnkunnige svenska män: R - S. Vol. 13. Upsala: Wahlström. 1847. p. 232.

- ^ Local.se. "Introducing... Christmas Tomte.". Retrieved 2 December 2013.

- ^ Schager Karin (1989) Julbocken i folktro och jultradition (Rabén & Sjögren)

- ^ Lucia Retrieved 2 December 2013

- ^ A Swedish Christmas song about Tomtar (gnomes) Archived 2013-12-03 at the Wayback Machine Retrieved 2 December 2013

- ^ Brett, Jan (2000). Hedgie's Surprise. G.P. Putnam's Sons Books for Young Readers. ISBN 978-0399234774

General bibliography

- Aasen, Ivar, ed. (1873). Norsk ordbog med dansk forklaring (3 ed.). P. T. Mallings bogtrykkeri.

- Asbjørnsen, Peter Christen, ed. (1896). Norske Folke- og Huldre-Eventyr (2nd ed.). Kjøbenhavn: Gyldendalske.

- Binding, Paul (2014). "4. O. T.". Hans Christian Andersen: European Witness. Yale University Press. ISBN 0300206151.

- Braekstad, H. L., ed. (1881). Round the Yule Log: Norwegian Folk and Fairy Tales. Translated by Braekstad, H. L. Peter Christen Asbjørnsen (orig. ed.). Nasjonalbiblioteket copy

- Bringsværd, Tor Åge (1970). Phantoms and Fairies: From Norwegian Folklore. Oslo: Tanum.

- Brynildsen, John [in Norwegian], ed. (1927). Norsk-engelsk ordbok. Oslo: H. Aschehoug & co. (W. Nygaard).

- Christiansen, Reidar, ed. (2016) [1964]. Folktales of Norway. Translated by Iversen, Pat Shaw. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 022637520X.

- Falk, Hjalmar; Torp, Alf, eds. (1906) [1964]. Etymologisk ordbog over det norske og det danske sprog. Vol. 2. Krisitiania: H. Aschehoug (W. NyGaard).

- Grønvik, Oddrun (1997). "Ordet nisse o. al i dei nynorske ordsamlingane" [The Word nisse and others in the Nynorsk Word Collection]. Mål og Minne (in Norwegian). 2: 149–156.

- Grønvik, Ottar (1997). "Nissen". Mål og Minne (in Norwegian). 2: 129–148.

- Knutsen, Gunnar W.; Riisøy, Anne Irene (2007). "Trolls and witches". Arv: Nordic Yearbook of Folklore. 63: 31–70.; pdf text via Academia.edu

- Kvideland, Reimund; Sehmsdorf, Henning K. (1988). "V. The Invisible Folk". Scandinavian Folk Belief and Legend. Vol. 15. University of Minnesota Press. pp. 205–274. ISBN 9780816615032. JSTOR 10.5749/j.ctttszpg.9.

- Stokker, Kathleen (2000). Keeping Christmas: Yuletide Traditions in Norway and the New Land. St. Paul: Minnesota Historical Society Press. ISBN 0873513894.

Related reading

- Vår svenska tomte, Ebbe Schön (1996), ISBN 91-27-05573-6

- Viktor Rydberg's The Tomten in English

- nisse, Kierkegaard, Concluding Unscientific Postscript (Hong, 1992), p. 40

- The Tomten, by Astrid Lindgren

External links

- "Tomten", poem in Swedish by Viktor Rydberg