Rice

It has been suggested that Parboiled rice be merged into this article. (Discuss) Proposed since September 2007. |

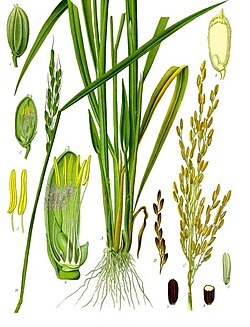

Domesticated rice Poaceae ("true grass") family, Oryza sativa and Oryza glaberrima. These plants are native to tropical and subtropical southern Asia and southeastern Africa.[1] Rice provides more than one fifth of the calories consumed worldwide by humans.[2] (The term "wild rice" can refer to the wild species of Oryza, but conventionally refers to species of the related genus Zizania, both wild and domesticated.) Rice is grown as a monocarpic annual plant, although in tropical areas it can survive as a perennial and can produce a ratoon crop[3] Rice can grow to 1–1.8 m tall, occasionally more depending on the variety and soil fertility. The grass has long, slender leaves 50–100 cm long and 2–2.5 cm broad. The small wind-pollinated flowers are produced in a branched arching to pendulous inflorescence 30–50 cm long. The seed is a grain(cryopsis) 5–12 mm long and 2–3 mm thick.

Rice is a staple for a large part of the world's human population, especially in East, South and Southeast Asia, making it the second most consumed cereal grain[4]. Rice cultivation is well-suited to countries and regions with low labour costs and high rainfall, as it is very labour-intensive to cultivate and requires plenty of water for cultivation[citation needed].

Rice can be grown practically anywhere, even on steep hill.Although its species are native to South Asia and certain parts of Africa, centuries of trade and exportation have made it commonplace in many cultures.

The traditional method for cultivating rice is flooding the fields with or after setting the young seedlings. This simple method requires sound planning and servicing of the water damming and channeling, but reduces the growth of lesser robust weed and pest plants and reduces vermin that has no submerged growth state. However, with rice growing and cultivation the flooding is not mandatory, whereas all other methods of irrigation require higher effort in weed and pest control during growth periods and a different approach for fertilizing the soil.

Preparation as food

The seeds of the rice plant are first milled using a rice huller to remove the chaff (the outer husks of the grain). At this point in the process the product is called brown rice. This process may be continued, removing the germ and the rest of the husk, called the bran at this point, creating white rice.

Whereas brown rice contains all of the ingredients of a healthy cereal, white rice, without the nutrients of rice germ and rice bran, is a standard in industrialized countries for commercial offerings. The former Beri-Beri disease was related to the stripping off of all ingredients of the bran, however the impact of aflatoxins and other mycotoxins contributed to the problem. Today, parboiling is a first method to move some of the nutrients from the bran to the rice corn before stripping the bran, however the energy requirements are high compared to dry processing technologies.

White rice may be also buffed with glucose or talc powder (often called polished rice, though this term may also refer to white rice in general), parboiled, or processed into flour. The white rice may also be enriched by adding nutrients, especially those lost during the milling process. While the cheapest method of enriching involves adding a powdered blend of nutrients that will easily wash off (in the United States, rice which has been so treated requires a label warning against rinsing), more sophisticated methods apply nutrients directly to the grain, coating the grain with a water insoluble substance which is resistant to washing.

Despite the hypothetical health risks of talc (such as stomach cancer), talc-coated rice remains the norm in some countries due to its attractive shiny appearance, but it has been banned in some and is no longer widely used in others such as the United States. Even where talc is not used, glucose, starch, or other coatings may be used to improve the appearance of the grains; for this reason, many rice lovers still recommend washing all rice in order to create a better-tasting rice with a better consistency, despite the recommendation of suppliers. Much of the rice produced today is water polished.[citation needed]

Rice bran, called nuka in Japan, is a valuable commodity in Asia and is used for many daily needs. It is a moist, oily inner layer which is heated to produce an oil. It is also used in making a kind of pickled vegetable.

The raw rice may be ground into flour for many uses, including making many kinds of beverages such as amazake, horchata, rice milk, and sake. Rice flour is generally safe for people on a gluten-free diet. Rice may also be made into various types of noodles. Raw wild or brown rice may also be consumed by raw foodist or fruitarians if soaked and sprouted (usually 1 week to 30 days).

The processed rice seeds are usually boiled or steamed to make them edible, after which they may be fried in oil or butter, or beaten in a tub to make mochi.

| Nutritional value per 100 g (3.5 oz) | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Energy | 1,506 kJ (360 kcal) | ||||||||||

79 g | |||||||||||

0.6 g | |||||||||||

7 g | |||||||||||

| |||||||||||

| Other constituents | Quantity | ||||||||||

| Water | 13 g | ||||||||||

| †Percentages estimated using US recommendations for adults,[5] except for potassium, which is estimated based on expert recommendation from the National Academies.[6] | |||||||||||

Although rice is a good source of protein and a staple food in many parts of the world, it is not a complete protein. That is, it does not contain all of the essential amino acids in sufficient amounts for good health, and should be combined with other sources of protein, like meat or soybeans.[7]

Rice, like other cereal grains, can be puffed (or popped). This process takes advantage of the grains' water content and typically involves heating grain pellets in a special chamber. Further puffing is sometimes accomplished by processing pre-puffed pellets in a low-pressure chamber. The ideal gas law means that either lowering the local pressure or raising the water temperature results in an increase in volume prior to water evaporation, resulting in a puffy texture. Bulk raw rice density is about 0.9 g/cm³. It decreases more than tenfold when puffed.

Cooking

Rice is cooked by boiling or steaming. It can be cooked in just enough water to cook it through (the absorption method), or it can be cooked in a large quantity of water which is drained before serving (the rapid-boil method). Electric rice cookers, which are popular in Asia and Latin America, simplify the process of cooking rice.

Also extremely popular are combinations; for example fried rice is boiled (or steamed) rice that has afterwards been stir-fried in oil.

Rice may also be made into rice porridge (also called congee or rice gruel) by adding more water than usual, so that the cooked rice is saturated with water to the point that it becomes very soft, expanded, and fluffy. Rice porridge is commonly eaten as a breakfast food, and is also traditionally a food for the sick.

Rice may be soaked prior to cooking, which decreases cooking time. For some varieties, soaking improves the texture of the cooked rice by increasing expansion of the grains.

In some culinary traditions, especially those of Latin America, Italy, and Turkey, dry rice grains are fried in oil before cooking in water.

In some countries, rice is commonly consumed as parboiled rice, also known as Minute rice™® or easy-cook rice. Parboiled rice is subjected to a steaming or parboiling process while still a brown rice. This causes nutrients from the outer husk to move into the grain itself. The parboil process causes a gelatisisation of the starch in the grains. The grains become less brittle, and the colour of the milled grain changes from white to yellow. The rice is then dried, and can then be milled as usual or consumed as brown rice. Milled parboil rice is nutritionally superior to standard milled rice. Parboiled rice has an additional benefit in that it does not stick to the pan during cooking as happens when cooking regular white rice.

A nutritionally superior method of preparing brown rice known as GABA Rice or GBR (Germinated Brown Rice)[8] may be used. This involves soaking washed brown rice for 20 hours in warm water (38 °C or 100 °F) prior to cooking it. This process stimulates germination, which activates various enzymes in the rice. By this method, a result of research carried out for the United Nations Year of Rice, it is possible to obtain a more complete amino acid profile, including GABA.

Cooked rice can contain Bacillus cereus spores which produce an emetic toxin when left between 4-60 degrees Celsius [7]. When storing cooked rice for use the next day, rapid cooling is advised to reduce the risk of contamination.

Production history

Etymology

According to the Microsoft Encarta Dictionary (2004) and the Chambers Dictionary of Etymology (1988), the word rice has an Indo-Iranian origin. It came to English from Greek óryza, via Latin oriza, Italian riso and finally Old French ris (the same as present day French riz).

It has been speculated that the Indo-Iranian vrihi itself is borrowed from a Dravidian vari (< PDr. *warinci)[9] or even a Munda language term for rice. The Tamil name ar-risi may have produced the Arabic ar-ruzz, from which the Portuguese and Spanish word arroz originated.

Genetic history

This article may be confusing or unclear to readers. (March 2008) |

Two species of rice were domesticated, Asian rice (O. sativa) and African rice (O. glaberrima). According to Londo and Chiang, O. sativa appears to have been domesticated from wild (Asian) rice, Oryza rufipogon around the foothills of the Himalayas, with O. sativa var. indica on the Indian side and O. sativa var. japonica on the Chinese and Japanese side.[10] The different histories have led to different ecological niches for the two main types of rice. Indica are mainly lowland rices, grown mostly submerged, throughout tropical Asia, while japonica are usually cultivated in dry fields, in temperate East Asia, upland areas of Southeast Asia and high elevations in South Asia. (Oka 1988) Current genetic analysis suggests that O. sativa would be best divided into five groups, labeled indica, aus, aromatic, temperate japonica and tropical japonica. The same analysis suggests that indica and aus are closely related, as are tropical japonica, temperate japonica, and aromatic.[11] Further analysis of the genetic material of various types of rice indicates that japonica was the first cultivar to emerge, followed by the indica, aus, and aromatic groups, whose genome did show significant differences in age. Within the japonica group, there is some genetic evidence that temperate japonica is derived from tropical japonica.[12]

Other studies have suggested that there are three groups of Oryza sativa cultivars: the short-grained "japonica" or "sinica" varieties, exemplified by Japanese rice; the long-grained "indica" varieties, exemplified by Basmati rice; and the broad-grained "javonica" varieties, which thrive under tropical conditions (Zohary and Hopf, 2000). The earliest find site for the japonica variety, dated to the fifth millennium BC, was in the earliest phases of the Hemudu culture on the south side of Hangzhou Bay in China, but was found along with japonica types.[citation needed]

Global History and Methodology of Cultivating Rice

South Asia

According to the Encyclopedia Brittanica:[13]

The origin of rice culture has been traced to India in about 3000 BC. Rice culture gradually spread westward and was introduced to southern Europe in medieval times. With the exception of the type called upland rice, the plant is grown on submerged land in the coastal plains, tidal deltas, and river basins of tropical, semitropical, and temperate regions. The seeds are sown in prepared beds, and when the seedlings are 25 to 50 days old, they are transplanted to a field, or paddy, that has been enclosed by levees and submerged under 5 to 10 cm (2 to 4 inches) of water, remaining submerged during the growing season.

Wild rice appeared in the Belan and Ganges valley regions of northern India as early as 4530 BC and 5440 BC respectively. Agricultural activity during the second millennium BC included rice cultivation in the Kashmir and mature Harrappan -Pakistan regions.[14] Mixed farming was the basis of Indus valley economy. Farmers planted their crops in integrated fields. Rice, grown on the west coast, was cultivated in the Indus valley.[15] Rice, along with barley, meat, dairy products and fish constituted the dietary staple of the ancient Dravidian people.[16]

There is mention of ApUpa, Puro-das and Odana (rice-gruel) in the Rig Veda, terms that refer to rice dishes,[17] The rigvedic commentator Sayana refers to "tandula" when commenting on RV 1.16.2., which means rice.[18] The Rigvedic term dhana (dhanaa, dhanya) means rice.[19] Both Charaka and Sushruta mention rice in detail.[20] The Arthasastra discusses aspects of rice cultivation.[21] The Kashyapiyakrishisukti by Kashyapa is the most detailed ancient Sanskrit text on rice cultivation.[22]

Continental East Asia

Z. Zhao, a Chinese palaeoethnobotanist, hypothesizes that people of the Late Pleistocene began to collect wild rice. Zhao explains that the collection of wild rice from an early date eventually led to its domestication and then the exclusive use of domesticated rice strains by circa 6400 BC at the latest.[23] Stone tool evidence from the Yunchanyan site in Hunan province suggests the possibility that Early Neolithic groups cultivated rice as early as circa 9000 BC.[24] Crawford and Shen point out that calibrated radiocarbon dates show that direct evidence of the earliest cultivated rice is no older than 7000 BC. Jared Diamond, a biologist and popular science author, summarizes some of the research done by archaeologists and estimates that the earliest attested domestication of rice took place in China by 7500 BC.[25]

An early archaeological site from which rice was excavated is Pengtoushan in the Hupei basin. This archaeological site was dated by AMS radiocarbon techniques to 6400–5800 BC (Zohary and Hopf 2000), but most of the Neolithic sites in China with finds of charred rice and radiocarbon dates are from 5000 BC or later.[26] This evidence leads most archaeologists to say that large-scale dry-land rice farming began between 5000 and 4500 BC in the area of Yangtze Delta (for example Hemudu culture, discovered in 1970s), and the wet-rice cultivation began at approximately 2500 BC in the same area (Liangzhu culture). It is now commonly thought that some areas such as the alluvial plains in Shaoxing and Ningbo in Zhejiang province are the cradle-lands of East Asian rice cultivation.[27] Finally, ancient textual evidence of the cultivation of rice in China dates to 3000 years ago.

Bruce Smith of the Smithsonian Institution advises caution on the Chinese rice hypothesis.[28] No morphological studies have been done to determine whether the grain was domesticated.[28] According to Smith such a rice would have larger seeds compared to the wild varieties, and would have a strong rachis or spine for holding grain.[28]

Korean peninsula and Japan

In 2003, Korean archaeologists alleged that they discovered burnt grains (domesticated rice) in Soro-ri, Korea, that predate the oldest grains in China. This find potentially challenges the mainstream explanation that domesticated rice originated in China.[29] The media reports of the Soro-ri charred grains are brief and lack sufficient detail for archaeologists and scientists in related fields to properly evaluate the true meaning of this unusual find.

Reliable, mainstream archaeological evidence derived from palaeoethnobotanical investigations indicate that dry-land rice was introduced to Korea and Japan some time between 3500 and 1200 BC. The cultivation of rice in Korea and Japan during that time occurred on a small-scale, fields were impermanent plots, and evidence shows that in some cases domesticated and wild grains were planted together. The technological, subsistence, and social impact of rice and grain cultivation is not evident in archaeological data until after 1500 BC. For example, intensive wet-paddy rice agriculture was introduced into Korea shortly before or during the Middle Mumun Pottery Period (c. 850–550 BC) and reached Japan by the Final Jōmon or Initial Yayoi circa 300 BC.[30][31]

Southeast Asia

Rice is a staple for all classes in contemporary Indonesia. Evidence of wild rice on the island of Sulawesi dates from 3000 BCE. Evidence for the earliest cultivation, however, comes from eighth century stone inscriptions from the central island of Java, which show kings levied taxes in rice. Divisions of labour between men, women, and animals that are still in place in Indonesian rice cultivation, can be seen carved into the ninth-century Prambanan temples in Central Java. In the sixteenth century, Europeans visiting the Indonesian islands saw rice as a new prestige food served to the aristocracy during ceremonies and feasts. Rice production in Indonesian history is linked to the development of iron tools and the domestication of water buffalo for cultivation of fields and manure for fertilizer. Once covered in dense forest, much of the Indonesian landscape has been gradually cleared for permanent fields and settlements as rice cultivation developed over the last fifteen hundred years.[32]

Evidence of wet rice cultivation as early as 2200 BC has been discovered at both Ban Chiang and Ban Prasat in Thailand.

Africa

African rice has been cultivated for 3500 years. Between 1500 and 800 BC, O. glaberrima propagated from its original centre, the Niger River delta, and extended to Senegal. However, it never developed far from its original region. Its cultivation even declined in favour of the Asian species, possibly brought to the African continent by Arabs coming from the east coast between the 7th and 11th centuries CE.

Near East and Europe

According to Zohary and Hopf (2000, p. 91), O. sativa was introduced to the Middle East in Hellenistic times, and was familiar to both Greek and Roman writers. They report that a large sample of rice grains was recovered from a grave at Susa in Iran (dated to the first century AD) at one end of the ancient world, while at the same time rice was grown in the Po valley in Italy. However, Pliny the Elder writes that rice (oryza) is grown only in "Egypt, Syria, Cilicia, Asia Minor and Greece" (N.H. 18.19). The Moors brought it to the Iberian Peninsula when they conquered it in 711. After the middle of the 15th century, rice spread throughout Italy and then France, later propagating to all the continents during the age of European exploration.

In the United States

In 1694, rice arrived in South Carolina, probably originating from Madagascar. The Spanish brought rice to South America at the beginning of the 17th century.

In the United States, colonial South Carolina and Georgia grew and amassed great wealth from the slave labour obtained from the Senegambia area of West Africa. At the port of Charleston, through which 40% of all American slave imports passed, slaves from this region of Africa brought the highest prices, in recognition of their prior knowledge of rice culture, which was put to use on the many rice plantations around Georgetown, Charleston, and Savannah. From the slaves, plantation owners learned how to dyke the marshes and periodically flood the fields. At first the rice was milled by hand with wooden paddles, then winnowed in sweetgrass baskets (the making of which was another skill brought by the slaves). The invention of the rice mill increased profitability of the crop, and the addition of water power for the mills in 1787 by millwright Jonathan Lucas was another step forward. Rice culture in the southeastern U.S. became less profitable with the loss of slave labour after the American Civil War, and it finally died out just after the turn of the 20th century. The predominant strain of rice in the Carolinas was from Africa and was known as "Carolina Gold." The cultivar has been preserved and there are current attempts to reintroduce it as a commercially grown crop.[33]

In the southern United States, rice has been grown in southern Arkansas, Louisana, and east Texas since the mid 1800s. Many Cajun farmers grew rice in wet marshes and low lying prairies. In recent years rice production has risen in North America, especially in the Mississippi River Delta areas in the states of Arkansas and Mississippi.

Rice cultivation began in California during the California Gold Rush, when an estimated 40,000 Chinese laborers immigrated to the state. In the book 1421, Gavin Menzies refers to stranded Chinese sailors cultivating rice in California when a ship was shipwrecked in the area. However, commercial production began only in 1912 in the town of Richvale in Butte County.[34] By 2006, California produced the second largest rice crop in the United States,[35] after Arkansas, with production concentrated in six counties north of Sacramento.[36] Unlike the Mississippi Delta region, California's production is dominated by short- and medium-grain japonica varieties, including cultivars developed for the local climate such as Calrose, which makes up as much as eighty five percent of the state's crop.[37]

References to wild rice in the Americas are to the unrelated Zizania palustris

More than 100 varieties of rice are commercially produced primarily in six states (Arkansas, Texas, Louisiana, Mississippi, Missouri, and California) in the U.S.[38] According to estimates for the 2006 crop year, rice production in the U.S. is valued at $1.88 billion, approximately half of which is expected to be exported. The U.S. provides about 12% of world rice trade.[39] The majority of domestic utilization of U.S. rice is direct food use (58%), while 16 percent is used in processed foods and beer respectively. The remaining 10 percent is found in pet food.[40]

Australia

Although attempts to grow rice in the well-watered north of Australia have been made for many years, they have consistently failed because of inherent iron and manganese toxicities in the soils and destruction by pests.

In the 1920s it was seen as a possible irrigation crop on soils within the Murray-Darling Basin that were too heavy for the cultivation of fruit and too infertile for wheat.[41]

Because irrigation water, despite the extremely low runoff of temperate Australia, was (and remains) very cheap, the growing of rice was taken up by agricultural groups over the following decades. Californian varieties of rice were found suitable for the climate in the Riverina, and the first mill opened at Leeton in 1951.

Even before this Australia's rice production greatly exceeded local needs,[42] and rice exports to Japan have become a major source of foreign currency. Above-average rainfall from the 1950s to the middle 1990s[43] encouraged the expansion of the Riverina rice industry, but its prodigious water use in a practically waterless region began to attract the attention of environmental scientists. These became severely concerned with declining flow in the Snowy River and the lower Murray River.

Although rice growing in Australia is exceedingly efficient and highly profitable due to the cheapness of land, several recent years of severe drought have led many to call for its elimination because of its effects on extremely fragile aquatic ecosystems. Politicians, however, have not made any plan to reduce rice growing in southern Australia.

Uruguay

The Eastern 'departmentos' of Uruguay have proved to be suitable for rice growth. Although production is supported with tax-relief and in some cases complete exemption, the country has been able to export to some international markets.

Rice Biotechnology

High Yielding Varieties

The High Yielding Varieties are a group of crops created intentionally during the Green Revolution to increase global food production. Rice, like corn and wheat, was genetically manipulated to increase its yield. This project enabled labor markets in Asia to shift away from agriculture, and into industrial sectors. The first ‘modern rice’, IR8 was produced in 1966 at the International Rice Research Institute. IR8 was created through a cross between an Indonesian variety named “Peta” and a Chinese variety named “Dee Geo Woo Gen.”[44]

With advances in molecular genetics, the mutant genes responsible for reduced height(rht), gibberellin insensitive (gai1) and slender rice (slr1) in Arabidopsis and rice were identified as cellular signaling components of gibberellic acid (a phytohormone involved in regulating stem growth via its effect on cell division) and subsequently cloned. Stem growth in the mutant background is significantly reduced leading to the dwarf phenotype. Photosynthetic investment in the stem is reduced dramatically as the shorter plants are inherently more stable mechanically. Assimilates become redirected to grain production, amplifying in particular the effect of chemical fertilizers on commercial yield. In the presence of nitrogen fertilizers, and intensive crop management, these varieties increase their yield 2 to 3 times.

Potentials for the Future

As the UN Millenium Development project seeks to spread global economic development to Africa, the ‘Green Revolution’ is cited as the model for economic development. With the intent of replicating the successful Asian boom in agronomic productivity, groups like the Earth Institute are doing research on African agricultural systems, hoping to increase productivity. An important way this can happen is the production of ‘New Rices for Africa’(NERICA). These rices, selected to tolerate the low input and harsh growing conditions of African agriculture are produced by the African Rice Center, and billed as technology from Africa, for Africa. The NERICA have appeared in the New York Times (October 10, 2007), and International Herald Tribune (October 9, 2007), trumpeted as miracle crops that will dramatically increase rice yield in Africa and enable an economic resurgence.

Golden Rice

German and Swiss researchers have engineered rice to produce Beta-carotene, with the intent that it might someday be used to treat vitamin A deficiency. Additional efforts are being made to improve the quantity and quality of other nutrients in golden rice.[45]

Expression of human proteins

Ventria Bioscience has genetically modified rice to express lactoferrin, lysozyme, and human serum albumin which are proteins usually found in breast milk. These proteins have antiviral, antibacterial, and antifungal effects.[46]

Rice containing these added proteins can be used as a component in oral rehydration solutions which are used to treat diarrheal diseases, thereby shortening their duration and reducing recurrence. Such supplements may also help reverse anemia.[47]

World production and trade

| Top paddy rice producers — 2005 (million metric ton) | |

|---|---|

| 182 | |

| 137 | |

| 54 | |

| 40 | |

| 36 | |

| 27 | |

| 25 | |

| 18 | |

| 15 | |

| 13 | |

| 11 | |

| World Total | 700 |

| Source: UN Food & Agriculture Organisation (FAO)[8] | |

World production of rice[48] has risen steadily from about 200 million tons of paddy rice in 1960 to 600 million tons in 2004. Milled rice is about 68% of paddy rice by weight. In the year 2004, the top three producers were China (26% of world production), India (20%), and Indonesia (9%).

World trade figures are very different, as only about 5–6% of rice produced is traded internationally. The largest three exporting countries are Thailand (26% of world exports), Vietnam (15%), and the United States (11%), while the largest three importers are Indonesia (14%), Bangladesh (4%), and Brazil (3%). Though China and India are largest producer of Rice in the world, the consumption of rice is significantly high in these countries, so international trade of Rice in India and China is not very popular.

Rice is the most important crop in Asia. In Cambodia, for example, 90% of the total agricultural area is used for rice production (see The Burning of the Rice by Don Puckridge for the story of rice production in Cambodia [9]).

Environmental impacts

In many countries where rice is the main cereal crop, rice cultivation is responsible for most of the methane emissions.[49] Farmers in some of the arid regions try to cultivate rice using groundwater bored through pumps, thus increasing the chances of famine in the long run.[citation needed] Rice also requires much more water to produce than other grains.[50]

Rice pests

Rice pests are any organisms or microbes with the potential to reduce the yield or value of the rice crop (or of rice seeds)[51] (Jahn et al 2007). Rice pests include weeds, pathogens, insects, rodents, and birds. A variety of factors can contribute to pest outbreaks, including the overuse of pesticides and high rates of nitrogen fertilizer application (e.g. Jahn et al. 2005)[10]. Weather conditions also contribute to pest outbreaks. For example, rice gall midge and army worm outbreaks tend to follow high rainfall early in the wet season, while thrips outbreaks are associated with drought (Douangboupha et al. 2006).

One of the challenges facing crop protection specialists is to develop rice pest management techniques which are sustainable. In other words, to manage crop pests in such a manner that future crop production is not threatened (Jahn et al. 2001). Rice pests are managed by cultural techniques, pest-resistant rice varieties, and pesticides (which include insecticide). Increasingly, there is evidence that farmers' pesticide applications are often unnecessary (Jahn et al. 1996, 2004a,b) [11][12][13]. By reducing the populations of natural enemies of rice pests (Jahn 1992), misuse of insecticides can actually lead to pest outbreaks (Cohen et al. 1994). Botanicals, so-called “natural pesticides”, are used by some farmers in an attempt to control rice pests, but in general the practice is not common. Upland rice is grown without standing water in the field. Some upland rice farmers in Cambodia spread chopped leaves of the bitter bush (Chromolaena odorata (L.)) over the surface of fields after planting. The practice probably helps the soil retain moisture and thereby facilitates seed germination. Farmers also claim the leaves are a natural fertilizer and helps suppress weed and insect infestations (Jahn et al. 1999).

Among rice cultivars there are differences in the responses to, and recovery from, pest damage (Jahn et al. 2004c, Khiev et al. 2000). Therefore, particular cultivars are recommended for areas prone to certain pest problems. Major rice pests include the brown planthopper[14] (Preap et al. 2006), armyworms[15], the green leafhopper, the rice gall midge (Jahn and Khiev 2004), the rice bug (Jahn et al. 2004c), hispa (Murphy et al. 2006), the rice leaffolder, stemborer, rats (Leung et al 2002), and the weed Echinochloa crusgali (Pheng et al. 2001). Major rice diseases include Rice Ragged Stunt, Sheath Blight and Tungro. Rice blast, caused by the fungus Magnaporthe grisea, is the most significant disease affecting rice cultivation.

Cultivars

The largest collection of rice cultivars is at the International Rice Research Institute (IRRI), with over 100,000 rice accessions [16] held in the International Rice Genebank [17]. Rice cultivars are often classified by their grain shapes and texture. For example, Thai Jasmine rice is long-grain and relatively less sticky, as long-grain rice contains less amylopectin than short-grain cultivars. Chinese restaurants usually serve long-grain as plain unseasoned steamed rice. Japanese mochi rice and Chinese sticky rice are short-grain. Chinese people use sticky rice which is properly known as "glutinous rice" (note: glutinous refer to the glue-like characteristic of rice; does not refer to "gluten") to make zongzi. The Japanese table rice is a sticky, short-grain rice. Japanese sake rice is another kind as well.

Indian rice cultivars include long-grained and aromatic Basmati (grown in the North), long and medium-grained Patna rice and short-grained Masoori. In South India the most prized cultivar is 'ponni' which is primarily grown in the delta regions of Kaveri River. Kaveri is also referred to as ponni in the South and the name reflects the geographic region where it is grown. Rice in East India and South India, is usually prepared by boiling the rice in large pans immediately after harvesting and before removing the husk; this is referred to in English as parboiled rice. It is then dried, and the husk removed later. It often displays small red speckles, and has a smoky flavour from the fires. Usually coarser rice is used for this procedure. It helps to retain the natural vitamins and kill any fungi or other contaminants, but leads to an odour which some find peculiar. In South India, it is also used to make idlis, dosas and several breakfast and tiffin items. In the Western Indian state of Maharashtra, a short grain variety called Ambemohar is very popular. this rice has a characteristic fragrance of Mango blossom.

Aromatic rices have definite aromas and flavours; the most noted cultivars are Thai fragrant rice, Basmati, Patna rice, and a hybrid cultivar from America sold under the trade name, Texmati. Both Basmati and Texmati have a mild popcorn-like aroma and flavour. In Indonesia there are also red and black cultivars.

High-yield cultivars of rice suitable for cultivation in Africa and other dry ecosystems called the new rice for Africa (NERICA) cultivars have been developed. It is hoped that their cultivation will improve food security in West Africa.

Draft genomes for the two most common rice cultivars, indica and japonica, were published in April 2002. Rice was chosen as a model organism for the biology of grasses because of its relatively small genome (~430 megabase pairs). Rice was the first crop with a complete genome sequence.[52] Basmati rice is the oldest, common progenitor for most types.

On December 16, 2002, the UN General Assembly declared the year 2004 the International Year of Rice. The declaration was sponsored by more than 40 countries.

See also

- Beaten rice

- Bhutanese red rice

- Black rice

- Brown rice syrup

- Forbidden rice

- FreeRice

- Inari

- Indonesian rice table

- Jasmine rice

- List of rice dishes

- List of rice varieties

- New Rice for Africa

- Protein per unit area

- Puffed rice

- Red rice

- Rice Belt

- Rice bran oil

- Rice ethanol

- Rice wine

- System of rice intensification

- White rice

Notes

- ^ Crawford, G.W. and C. Shen. 1998. The Origins of Rice Agriculture: Recent Progress in East Asia. Antiquity 72:858–866.

- ^ Smith, Bruce D. The Emergence of Agriculture. Scientific American Library, A Division of HPHLP, New York, 1998.

- ^ International Rice Research Institute The Rice Plant and How it Grows Retrieved January 29, 2008 from http://www.knowledgebank.irri.org/riceIPM/IPM_Information/PestEcologyBasics/CropGrowthAndPestDamage/RicePlantHowItGrows/The_Rice_plant_and_How_it_Grows.htm.

- ^ "ProdSTAT". FAOSTAT. Retrieved 2006-12-26.

- ^ United States Food and Drug Administration (2024). "Daily Value on the Nutrition and Supplement Facts Labels". FDA. Archived from the original on 2024-03-27. Retrieved 2024-03-28.

- ^ National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine; Health and Medicine Division; Food and Nutrition Board; Committee to Review the Dietary Reference Intakes for Sodium and Potassium (2019). Oria, Maria; Harrison, Meghan; Stallings, Virginia A. (eds.). Dietary Reference Intakes for Sodium and Potassium. The National Academies Collection: Reports funded by National Institutes of Health. Washington, DC: National Academies Press (US). ISBN 978-0-309-48834-1. PMID 30844154. Archived from the original on 2024-05-09. Retrieved 2024-06-21.

- ^ Jianguo G. Wu (2003). "Estimating the amino acid composition in milled rice by near-infrared reflectance spectroscopy". Field Crops Research. Retrieved 2008-01-08.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Shoichi Ito and Yukihiro Ishikawa Tottori University, Japan. "(Marketing of Value-Added Rice Products in Japan: Germinated Grown Rice and Rice Bread.)".

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|accessmonthday=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|accessyear=ignored (|access-date=suggested) (help) - ^ Krishnamurti, Bhadriraju (2003) The Dravidian Languages Cambridge University Press, Cambridge. ISBN 0-521-77111-0 at p. 5.

- ^ J.P. Londo, Y. Chiang et al, "Phylogeography of Asian wild rice, Oryza rufipogon, reveals multiple independent domestications of cultivated rice, Oryza sativa", PNAS 103(25):9578–83, 2006 ([1])

- ^ Garris, Amanda, Tai, Thomas, Coburn, Jason, Kresovich, Steve, McCouch, Susan. 2004. “Genetic Structure and Diversity in Oryza sativa L.” [2]

- ^ Garris, Amanda, Tai, Thomas, Coburn, Jason, Kresovich, Steve, McCouch, Susan. 2004. “Genetic Structure and Diversity in Oryza sativa L.” [3]

- ^ "rice." Encyclopaedia Britannica 2008. Chicago: Encyclopædia Britannica, 2008.

- ^ Sorghum: Origin, History, Technology, and Production By C. Wayne Smith. Published 2000. John Wiley and Sons. ISBN 0471242373

- ^ World History: Societies of the Past / Charles Kahn ... [et Al.] By Charles Kahn. Published 2005. Portage & Main Press. ISBN 1553790456. pg 92

- ^ Food Culture in India By Colleen Taylor. Sen. Published 2004. Greenwood Press. ISBN 0313324875

- ^ Cf. Talageri (2000) Talageri, Shrikant: The Rigveda: A Historical Analysis, 2000. ISBN 81-7742-010-0

- ^ Rice Research in South Asia through Ages by Y L Nene, Asian Agri-History Vol. 9, No. 2, 2005 (85–106). With reference to Sontakke and Kashikar, 1983

- ^ Rice Research in South Asia through Ages by Y L Nene, Asian Agri-History Vol. 9, No. 2, 2005 (85–106).

- ^ Rice Research in South Asia through Ages by Y L Nene, Asian Agri-History Vol. 9, No. 2, 2005 (85–106).

- ^ Rice Research in South Asia through Ages by Y L Nene, Asian Agri-History Vol. 9, No. 2, 2005 (85–106).

- ^ Rice Research in South Asia through Ages by Y L Nene, Asian Agri-History Vol. 9, No. 2, 2005 (85–106).

- ^ Zhao, Z. 1998. The Middle Yangtze Region in China is the Place Where Rice was Domesticated: Phytolithic Evidence from the Diaotonghuan Cave, Northern Jiangxi. Antiquity 72:885–897.

- ^ Crawford and Shen 1998

- ^ Diamond, Jared (1999). Guns, Germs, and Steel: The Fates of Human Societies. New York: W.W. Norton & Company. ISBN 0-393-31755-2.

- ^ Crawford and Shen 1998

- ^ Crawford and Shen 1998

- ^ a b c "Earliest Rice" by Spencer P.M. Harrington in Archaeology June 11, 1997. Archaeological Institute of America (1997).

- ^ Cf. BBC news (2003) [4]

- ^ Crawford, G.W. and G.-A. Lee. 2003. Agricultural Origins in the Korean Peninsula. Antiquity 77(295):87–95.

- ^ Crawford and Shen 1998

- ^ Taylor, Jean Gelman (2003). Indonesia: Peoples and Histories. New Haven and London: Yale University Press. pp. pages 8-9. ISBN 0-300-10518-5.

{{cite book}}:|pages=has extra text (help) - ^ http://www.carolinagoldricefoundation.org/ Carolina Gold Rice Foundation

- ^ Ching Lee (2005). "Historic Richvale — the birthplace of California rice". California Farm Bureau Federation. Retrieved 2007-08-10.

- ^ "California's Rice Growing Region". California Rice Commission. Retrieved 2007-08-10.

- ^ Daniel A. Sumner (2003). "The economic contributions of the California rice industry"". California Rice Commission. Retrieved 2007-08-10.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ "Medium Grain Varieties". California Rice Commission. Retrieved 2007-08-10.

- ^ States Department of Agriculture August 2006, Release No. 0306.06, U.S. RICE STATISTICS

- ^ States Department of Agriculture August 2006, Release No. 0306.06, U.S. RICE STATISTICS

- ^ States Department of Agriculture August 2006, Release No. 0306.06, U.S. RICE STATISTICS

- ^ Wadham, Sir Samuel; Wilson, R. Kent and Wood, Joyce; Land Utilization in Australia, 3rd ed. Published 1957 by Melbourne University Press; p. 246

- ^ Ibid.

- ^ Australian Bureau of Meteorology; Climatic Atlas of Australia: Rainfall; published 2000 by Bureau of Meteorology, Melbourne, Victoria

- ^ Rice Varieties: IRRI Knowledge Bank. Accessed August 2006. [5]

- ^ Grand Challenges in Global Health, Press release, June 27, 2005

- ^ Nature's story

- ^ Bethell D. R., Huang J., et al. BioMetals, 17. 337 - 342 (2004).[6]

- ^ all figures from UNCTAD 1998–2002 and the International Rice Research Institute statistics (accessed September 2005)

- ^ Methane Emission from Rice Fields - Wetland rice fields may make a major contribution to global warming by Heinz-Ulrich Neue

- ^ report12.pdf

- ^ Jahn et al. 2000

- ^ Gillis, Justing (August 11, 2005). "Rice Genome Fully Mapped". washingtonpost.com.

References

- Cohen, J. E., K. Schoenly, K. L. Heong, H. Justo, G. Arida, A. T. Barrion, J. A. Litsinger. 1994. A Food Web Approach to Evaluating the Effect of Insecticide Spraying on Insect Pest Population Dynamics in a Philippine Irrigated Rice Ecosystem. Journal of Applied Ecology, Vol. 31, No. 4, pp. 747–763. doi:10.2307/2404165

- Crawford, G.W. and C. Shen. 1998. The Origins of Rice Agriculture: Recent Progress in East Asia. Antiquity 72:858–866.

- Crawford, G.W. and G.-A. Lee. 2003. Agricultural Origins in the Korean Peninsula. Antiquity 77(295):87–95.

- Douangboupha, B., K. Khamphoukeo, S. Inthavong, J. Schiller, and G. Jahn. 2006. Pests and diseases of the rice production systems of Laos. Pp. 265–281. In J.M. Schiller, M.B. Chanphengxay, B. Linquist, and S. Appa Rao, editors. Rice in Laos. Los Baños (Philippines): International Rice Research Institute. 457 p. ISBN 978-971-22-0211-7.

- Heong, KL, YH Chen, DE Johnson, GC Jahn, M Hossain, RS Hamilton. 2005. Debate Over a GM Rice Trial in China. Letters. Science, Vol 310, Issue 5746, 231–233 , 14 October 2005.

- Huang, J., Ruifa Hu, Scott Rozelle, Carl Pray. 2005. Insect-Resistant GM Rice in Farmers' Fields: Assessing Productivity and Health Effects in China. Science (29 April 2005) Vol. 308. no. 5722, pp. 688–690. DOI: 10.1126/science.1108972

- Jahn, G. C. 1992. Rice pest control and effects on predators in Thailand. Insecticide & Acaricide Tests 17:252–253.

- Jahn, GC and B. Khiev. 2004. Gall midge in Cambodian lowland rice. pp. 71–76. In J. Benett, JS Bentur, IC Pasula, K. Krishnaiah, [eds]. New approaches to gall midge resistance in rice. Los Baños (Philippines): International Rice Research Institute and Indian Council of Agricultural Research. 195 p.

- Jahn, G. C., S. Pheng, B. Khiev, and C. Pol. 1996. Farmers’ pest management and rice production practices in Cambodian lowland rice. Cambodia-IRRI-Australia Project (CIAP), Baseline Survey Report No. 6. CIAP Phnom Penh, Cambodia, 28 pages. [18]

- Jahn, G. C., B. Khiev, S. Pheng, and C. Pol. 1997. Pest management in rice. In H. J. Nesbitt [ed.] "Rice Production in Cambodia." Manila (Philippines): International Rice Research Institute. 83–91.

- Jahn, G. C., S. Pheng, B. Khiev, and C. Pol. 1997. Pest management practices of lowland rice farmers in Cambodia. In K. L. Heong and M. M. Escalada [editors] "Pest Management Practices of Rice Farmers in Asia." Manila (Philippines): International Rice Research Institute. 35–52. ISBN 971-22-0102-3

- Jahn, G. C., C. Pol, B. Khiev, S. Pheng, and N. Chhorn. 1999. Farmer’s pest management and rice production practices in Cambodian upland and deepwater rice. Cambodia-IRRI-Australia Project, Baseline Survey Report No. 7.[19]

- Jahn, G. C., S. Pheng, B. Khiev and C. Pol 2000. Ecological characterization of biotic constraints to rice in Cambodia. International Rice Research Notes (IRRN) 25 (3): 23–24.

- Jahn, G. C., S. Pheng, C. Pol, B. Khiev 2000. Characterizing biotic constraints to production of Cambodian rainfed lowland rice: limitations to statistical techniques. pp. 247–268 In T. P. Tuong, S. P. Kam, L. Wade, S. Pandey, B. A. M. Bouman, B. Hardy [eds.] “Characterizing and Understanding Rainfed Environments.” Proceedings of the International Workshop on Characterizing and Understanding Rainfed Environments, 5–9 December 1999, Bali, Indonesia. Los Baños (Philippines): International Rice Research Institute (IRRI). 488 p.

- Jahn, GC, B. Khiev, C. Pol, N. Chhorn, S. Pheng, and V. Preap. 2001. Developing sustainable pest management for rice in Cambodia. pp. 243–258, In S. Suthipradit, C. Kuntha, S. Lorlowhakarn, and J. Rakngan [eds.] “Sustainable Agriculture: Possibility and Direction” Proceedings of the 2nd Asia-Pacific Conference on Sustainable Agriculture 18–20 October 1999, Phitsanulok, Thailand. Bangkok (Thailand): National Science and Technology Development Agency. 386 p.

- Jahn, GC, NQ Kamal, S Rokeya, AK Azad, NI Dulu, JB Orsini, A Barrion, and L Almazan. 2004a. Completion Report on Livelihood Improvement Through Ecology (LITE), PETRRA IPM Subproject SP 27 02. Poverty Elimination Through Rice Research Assistance (PETRRA), IRRI, Dhaka. 20 pages text plus 20 pages appendices. [20]

- Jahn, GC, NQ Kamal, S Rokeya, AK Azad, NI Dulu, JB Orsini, M Morshed, NMS Dhar, NA Kohinur 2004b. Evaluation Report on Livelihood Improvement Through Ecology (LITE), PETRRA IPM Subproject SP 27 02. Poverty Elimination Through Rice Research Assistance (PETRRA), IRRI, Dhaka. 42 pages plus 40 pages of annexes.[21]

- Jahn, GC, I. Domingo, L. P. Almazan and J. Pacia. 2004c. Effect of rice bugs (Alydidae: Leptocorisa oratorius (Fabricius)) on rice yield, grain quality, and seed viability. Journal of Economic Entomology 97(6): 1923–1927.[22]

- Jahn, GC, LP Almazan, and J Pacia. 2005. Effect of nitrogen fertilizer on the intrinsic rate of increase of the rusty plum aphid, Hysteroneura setariae (Thomas) (Homoptera: Aphididae) on rice (Oryza sativa L.). Environmental Entomology 34 (4): 938–943.[23]

- Jahn, GC, JA Litsinger, Y Chen and A Barrion. 2007. Integrated Pest Management of Rice: Ecological Concepts. In Ecologically Based Integrated Pest Management (eds. O. Koul and G.W. Cuperus). CAB International Pp. 315–366.

- Khiev, B., G. C. Jahn, C. Pol, and N. Chhorn 2000. Effects of simulated pest damage on rice yields. IRRN 25 (3): 27–28.

- Leung LKP, Peter G. Cox, Gary C. Jahn and Robert Nugent. 2002. Evaluating rodent management with Cambodian rice farmers. Cambodian Journal of Agriculture Vol. 5, pp. 21–26.

- Murphy, S, J Stonehouse, J Holt, J Venn, NQ Kamal, MF Rabbi, MH Haque, G Jahn, B Barrion. 2006. Ecology and management of rice hispa (Dicladispa armigera) in Bangladesh. Pp. 162––164. In Perspectives on Pests II: Achievements of research under UK Department for International Development, Crop Protection Programme 2000–05. Natural Resources International Limited. 206 pages. [24]

- Pheng, S., B. Khiev, C. Pol and G. C. Jahn 2001. Response of two rice cultivars to the competition of Echinochloa crus-gali (L.) P. Beauv. International Rice Research Institute Notes (IRRN) 26 (2): 36–37.

- Preap V., M. P. Zalucki and G. C. Jahn. 2006. Brown planthopper outbreaks and management. Cambodian Journal of Agriculture 7(1): 17–25.

- Preap, V, GC Jahn, K Hin, N Siheng. 2005. Fish and rice management system to enable agricultural diversification. Paper presented at the 5th Asia-Pacific Congress of Entomology, 18–21 October 2005, Jeju, Korea.

- Saltini Antonio, I semi della civiltà. Grano, riso e mais nella storia delle società umane,, prefazione di Luigi Bernabò Brea Avenue Media, Bologna 1996

- Rice Research in South Asia through Ages by Y L Nene, Asian Agri-History Vol. 9, No. 2, 2005 (85–106) [25]

- Daniel Zohary and Maria Hopf, Domestication of plants in the Old World, third edition Oxford: University Press, 2000.

- Zhao, Z. 1998. The Middle Yangtze Region in China is the Place Where Rice was Domesticated: Phytolithic Evidence from the Diaotonghuan Cave, Northern Jiangxi. Antiquity 72:885–897.

External links

General

- Infocomm/UNCTAD

- International Rice Research Institute

- Rice Knowledge Bank

- A Brief History of Rice

- Rice Research in South Asia through Ages (PDF)

Rice research & development

- Intensify to Diversify: an IRRI rice intensification project in Cambodia

- Celebrating the Land (Part 1): video about an IRRI project to increase rice production in Laos

- Celebrating the Land (Part 2): video about an IRRI project to increase rice production in Laos

- Operation Rice Bowl of the Catholic Relief Service

- Rice-Fish Culture in China, an IDRC Project

- JICA rice project in Bolivia

Rice in agriculture

- American Phytopathological Society: Diseases of Rice (Oryza sativa)

- FAO: Animal Feed Resources Information System, Oryza sativa

- Origin of Chinese rice cultivation

Rice as food

- How to Cook Rice Step-by-Step Photos

- US Patent 6,676,983: Puffed food starch product

- How to Save a Bad Batch of Rice and Other Tips

- Veetee DINE IN Microwavable Steam Cooked Rice

- A Malaysian Food Heritage

Rice ethanol fuel

Rice economics

- Rice as a Commodity

- UNCTAD market information

- Grain Drain: The Hidden Cost of U.S. Rice Subsidies

- Vietnamese Rice Website

Rice genome

- Rice Genome Browser

- n:Chinese authorities question genetically altered rice allegation

- Oryza sativa The rice genome, a "Rosetta stone" for other cereals

- Rice Genome Research Program

- Rice Genome Approaches Completion

- The Genomes of Oryza sativa: A History of Duplications

- Biologists Trace Back Genetic Origins Of Rice Domestication

- Waterproof rice can outlast the floods — Researchers have tracked down a gene that allows the plant to survive complete submersion