Democracy

| Part of the Politics series |

| Democracy |

|---|

|

|

Democracy is the system of rule by the people (from Greek: dēmos people, krateein to rule) which is, as in a sense currently understood and most frequently used, the rule by majority. If not restricted by a special system of check and balances, that rule can easily deterioriate into unrestricted rule of majority (or whoever claims to represent a majority) which is the same as tyranny.

In political theory, democracy describes a small number of related forms of government and also a political philosophy. A common feature of democracy as currently understood and practiced is competitive elections. Competitive elections are usually seen to require freedom of speech, freedom of the press, and some degree of rule of law. Civilian control of the military is often seen as necessary to prevent military dictatorship and interference with political affairs. In some countries, democracy is based on the philosophical principle of equal rights.

"Majority rule" is a major principle of democracy, though many democratic systems do not adhere to this strictly—representative democracy is more common than direct democracy, and minority rights are often protected from what is sometimes called "the tyranny of the majority". Popular sovereignty is common but not a universal motivating philosophy for establishing a democracy.

No universally accepted definition of 'democracy' exists, especially with regard to the elements in a society which are required for it.[1] Many people use the term "democracy" as shorthand for liberal democracy, which may include additional elements such as political pluralism, equality before the law, the right to petition elected officials for redress of grievances, due process, civil liberties, human rights, and elements of civil society outside the government. In the United States, separation of powers is often cited as a supporting attribute, but in other countries, such as the United Kingdom, the dominant philosophy is parliamentary sovereignty (though in practice judicial independence is generally maintained). In other cases, "democracy" is used to mean direct democracy.

Though the term "democracy" is typically used in the context of a political state, the principles are also applicable to private organizations and other groups. Democracy has its origins in Ancient Greece, Ancient Rome, Europe, and North and South America[2] but modern conceptions are significantly different. Democracy has been called the "last form of government" and has spread considerably across the globe.[3] Suffrage has been expanded in many jurisdictions over time from relatively narrow groups (such as wealthy men of a particular ethnic group), but still remains a controversial issue with regard disputed territories, areas with significant immigration, and countries that exclude certain demographic groups.

| Part of the Politics series |

| Basic forms of government |

|---|

| List of countries by system of government |

|

|

Etymology

The word democracy derives from the ancient Greek dēmokratia (δημοκρατία) (literally, rule by the people) formed from the roots dēmos (δήμος), "people,"[4] "the mob, the many"[5] and kratos (κράτος) "rule" or "power".[6]

Forms of democracy

Representative

Representative democracy involves the selection of government officials by the people being represented. The most common mechanisms involve election of the candidate with a majority or a plurality of the votes.

Representatives may be elected or become diplomatic representatives by a particular district (or constituency), or represent the entire electorate proportionally proportional systems, with some using a combination of the two. Some representative democracies also incorporate elements of direct democracy, such as referendums. A characteristic of representative democracy is that while the representatives are elected by the people to act in their interest, they retain the freedom to exercise their own judgment as how best to do so.

Parliamentary democracy

Parliamentary democracy where government is appointed by parliamentary representatives as opposed to a 'presidential rule' by decree dictatorship. Under a parliamentary democracy government is exercised by delegation to an executive ministry and subject to ongoing review, checks and balances by the legislative parliament elected by the peple.[7][8][9][10][11][12][13][14]

Liberal democracy

A Liberal democracy is a representative democracy in which the ability of the elected representatives to exercise decision-making power is subject to the rule of law, and usually moderated by a constitution that emphasizes the protection of the rights and freedoms of individuals, and which places constraints on the leaders and on the extent to which the will of the majority can be exercised against the rights of minorities (see civil liberties).

Direct Democracy

Direct democracy is a political system where the citizens participate in the decision-making personally, contrary to relying on intermediaries or representatives. The supporters of direct democracy argue that democracy is more than merely a procedural issue (i.e., voting).[15] Most direct democracies to date have been weak forms, relatively small communities, usually city-states. However, some see the extensive use of referendums, as in California, as akin to direct democracy in a very large polity with more than 20 million in California, 1898-1998 (2000) (ISBN 0-8047-3821-1). In Switzerland, five million voters decide on national referendums and initiatives two to four times a year; direct democratic instruments are also well established at the cantonal and communal level. Vermont towns have been known for their yearly town meetings, held every March to decide on local issues.

Socialist Democracy

Socialist thought has several different views on democracy. Social democracy, democratic socialism, and the dictatorship of the proletariat (usually exercised through Soviet democracy) are some examples. Many democratic socialists and social democrats believe in a form of participatory democracy and workplace democracy combined with a representative democracy.

Within Marxist orthodoxy there is a hostility to what is commonly called "liberal democracy", which they simply refer to as parliamentary democracy because of its often centralized nature. Because of their desire to eliminate the political elitism they see in capitalism, Marxists, Leninists and Trotskyists believe in direct democracy implemented though a system of communes (which are sometimes called soviets). This system ultimately manifests itself as council democracy and begins with workplace democracy. (See Democracy in Marxism)

Anarchist Democracy

The only form of democracy considered acceptable to many anarchists is direct democracy. Some anarchists oppose direct democracy while others favour it. Pierre-Joseph Proudhon argued that the only acceptable form of direct democracy is one in which it is recognized that majority decisions are not binding on the minority, even when unanimous.[16] However, anarcho-communist Murray Bookchin criticized individualist anarchists for opposing democracy,[17] and says "majority rule" is consistent with anarchism.[18] Some anarcho-communists oppose the majoritarian nature of direct democracy, feeling that it can impede individual liberty and opt in favour of a non-majoritarian form of consensus democracy, similar to Proudhon's position on direct democracy.[19]

Iroquois Democracy

Iroquois society had a form of participatory democracy and representative democracy.[20] Iroquois government and law was discussed by Benjamin Franklin[21] and Thomas Jefferson.[22] Because of this many scholars regard it to have influenced the formation of American representative democracy.[22] However scholars who reject multiculturalism disagree that the influence existed or was of any great importance.[23]

Sortition

Sometimes called "democracy without elections", sortition is the process of choosing decision makers via a random process. The intention is that those chosen will be representative of the opinions and interests of the people at large, and be more fair and impartial than an elected official. The technique was in widespread use in Athenian Democracy and is still used in modern jury selection. It is not universally agreed that sortition should be considered "democracy" due to the lack of actual elections[citation needed].

Consensus democracy

Consensus democracy requires varying degrees of consensus rather than just a mere democratic majority. It typically attempts to protect minority rights from domination by majority rule.

Interactive Democracy

Interactive Democracy seeks to utilise information technology to involve voters in law making. It provides a system for proposing new laws, prioritising proposals, clarifying them through parliament and validating them through referendum.

History

Ancient origins

One of the earliest instances of civilizations with democracy, or sometimes disputed as oligarchy, was found in the republics of ancient India, which were established sometime before the 6th century BC, and prior to the birth of Gautama Buddha. These republics were known as Maha Janapadas, and among these states, Vaishali (in what is now Bihar, India) would be the world's first republic. The democratic Sangha, Gana and Panchayat systems were used in some of these republics; the Panchayat system is still used today in Indian villages. Later during the time of Alexander the Great in the 4th century BC, the Greeks wrote about the Sabarcae and Sambastai states in what is now Pakistan and Afghanistan, whose "form of government was democratic and not regal" according to Greek scholars at the time.[26]

The term democracy first appeared in ancient Greek political and philosophical thought. The philosopher Plato contrasted democracy, the system of "rule by the governed", with the alternative systems of monarchy (rule by one individual), oligarchy (rule by a small élite class) and timocracy.[27] Although Athenian democracy is today considered by many to have been a form of direct democracy, originally it had two distinguishing features: firstly the allotment (selection by lot) of ordinary citizens to government offices and courts,[28] and secondarily the assembly of all the citizens. All the male Athenian citizens were eligible to speak and vote in the Assembly, which set the laws of the city-state, but neither political rights, nor citizenship, were granted to women, slaves, or metics. Of the 250,000 inhabitants only some 30,000 on average were citizens. Of those 30,000 perhaps 5,000 might regularly attend one or more meetings of the popular Assembly. Most of the officers and magistrates of Athenian government were allotted; only the generals (strategoi) and a few other officers were elected.[29]

The Roman Republic had elections but again women, slaves, and the large foreign population were excluded. The votes of the wealthy were given more weight and almost all high officials come from a few noble families.[30]

Democracy was also seen to a certain extent in bands and tribes such as the Iroquois Confederacy. However, in the Iroquois Confederacy only the males of certain clans could be leaders and some clans were excluded. Only the oldest females from the same clans could choose and remove the leaders. This excluded most of the population. An interesting detail is that there should be consensus among the leaders, not majority support decided by voting, when making decisions.[31][32] Band societies, such as the Bushmen, which usually number 20-50 people in the band often do not have leaders and make decisions based on consensus among the majority. In Melanesia, farming village communities have traditionally been egalitarian and lacking in a rigid, authoritarian hierarchy. Although a "Big man" or "Big woman" could gain influence, that influence was conditional on a continued demonstration of leadership skills, and on the willingness of the community. Every person was expected to share in communal duties, and entitled to participate in communal decisions. However, strong social pressure encouraged conformity and discouraged individualism.[33]

Middle Ages

During the Middle Ages, there were various systems involving elections or assemblies, although often only involving a minority of the population, such as the election of Gopala in Bengal, the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, the Althing in Iceland, certain medieval Italian city-states such as Venice, the tuatha system in early medieval Ireland, the Veche in Novgorod and Pskov Republics of medieval Russia, Scandinavian Things, The States in Tyrol and Switzerland and the autonomous merchant city of Sakai in the 16th century in Japan. However, participation was often restricted to a minority, and so may be better classified as oligarchy. Most regions during the middle-ages were ruled by clergy or feudal lords.

The Parliament of England had its roots in the restrictions on the power of kings written into Magna Carta. The first elected parliament was De Montfort's Parliament in England in 1265. However only a small minority actually had a voice; Parliament was elected by only a few percent of the population (less than 3% in 1780.[34]), and the system had problematic features such as rotten boroughs. The power to call parliament was at the pleasure of the monarch (usually when he or she needed funds). After the Glorious Revolution of 1688, the English Bill of Rights was enacted in 1689, which codified certain rights and increased the influence of the Parliament.[34] The franchise was slowly increased and the Parliament gradually gained more power until the monarch became largely a figurehead.[35]

18th and 19th centuries

Although not described as a democracy by the founding fathers, the United States has been described as the first liberal democracy on the basis that its founders shared a commitment to the principle of natural freedom and equality.[36] The United States Constitution, adopted in 1788, provided for an elected government and protected civil rights and liberties. However, in the colonial period before 1776, only adult white male property owners could vote; enslaved Africans, free black people and women were not extended the franchise. On the American frontier, democracy became a way of life, with widespread social, economic and political equality.[37] However the frontier did not produce much democracy in Canada, Australia or Russia. By the 1840s almost all property restrictions were ended and nearly all white adult male citizens could vote; and turnout averaged 60-80% in frequent elections for local, state and national officials. The system gradually evolved, from Jeffersonian Democracy to Jacksonian Democracy and beyond. In Reconstruction after the Civil War (late 1860s) the newly freed slaves became citizens with (in the case of men) the right to vote.

In 1789, Revolutionary France adopted the Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen and, although short-lived, the National Convention was elected by all males.[38]

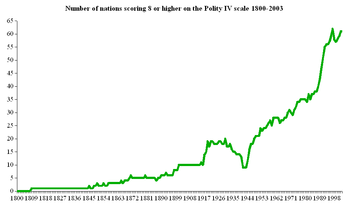

Liberal democracies were few and often short-lived before the late nineteenth century. Various nations and territories have claimed to be the first with universal suffrage.

20th century

20th century transitions to liberal democracy have come in successive "waves of democracy," variously resulting from wars, revolutions, decolonization, and economic circumstances. World War I and the dissolution of the Ottoman and Austro-Hungarian empires resulted in the creation of new nation-states in Europe, most of them at least nominally democratic. In the 1920s democracy flourished, but the Great Depression brought disenchantment, and most of the countries of Europe, Latin America, and Asia turned to strong-man rule or dictatorships. Fascism and dictatorships flourished in Nazi Germany, Italy, Spain and Portugal, as well as nondemocratic regimes in the Baltics, the Balkans, Brazil, Cuba, China, and Japan, among others.[39]

World War II brought a definitive reversal of this trend in western Europe. The successful democratization of the American, British, and French sectors of occupied Germany (disputed [2]), Austria, Italy, and the occupied Japan served as a model for the later theory of regime change. However, most of Eastern Europe, including the Soviet sector of Germany was forced into the non-democratic Soviet bloc. The war was followed by decolonization, and again most of the new independent states had nominally democratic constitutions. India, however emerged as the world's largest democracy and continues to be so.[40] In the decades following World War II, most western democratic nations had mixed economies and developed a welfare state, reflecting a general consensus among their electorates and political parties. In the 1950s and 1960s, economic growth was high in both the western and Communist countries; it later declined in the state-controlled economies. By 1960, the vast majority of nation-states were nominally democracies, although the majority of the world's populations lived in nations that experienced sham elections, and other forms of subterfuge (particularly in Communist nations and the former colonies.)

A subsequent wave of democratization brought substantial gains toward true liberal democracy for many nations. Spain, Portugal (1974), and several of the military dictatorships in South America returned to civilian rule in the late 1970s and early 1980s (Argentina in 1983, Bolivia, Uruguay in 1984, Brazil in 1985, and Chile in the early 1990s). This was followed by nations in East and South Asia by the mid- to late 1980s. Economic malaise in the 1980s, along with resentment of communist oppression, contributed to the collapse of the Soviet Union, the associated end of the Cold War, and the democratization and liberalization of the former Eastern bloc countries. The most successful of the new democracies were those geographically and culturally closest to western Europe, and they are now members or candidate members of the European Union [citation needed] . The liberal trend spread to some nations in Africa in the 1990s, most prominently in South Africa. Some recent examples of attempts of liberalization include the Indonesian Revolution of 1998, the Bulldozer Revolution in Yugoslavia, the Rose Revolution in Georgia, the Orange Revolution in Ukraine, the Cedar Revolution in Lebanon, and the Tulip Revolution in Kyrgyzstan.

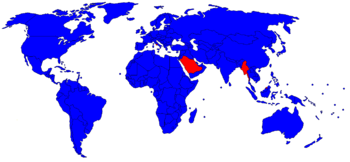

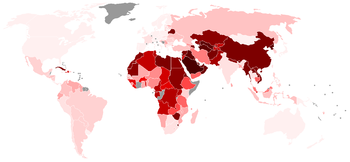

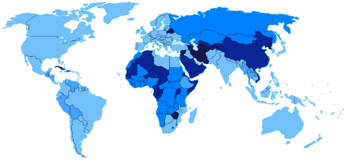

Currently, there are 121 countries that are democratic, and the trend is increasing[41] (up from 40 in 1972)[citation needed]. As such, it has been speculated that this trend may continue in the future to the point where liberal democratic nation-states become the universal standard form of human society. This prediction forms the core of Francis Fukayama's "End of History" controversial theory. These theories are criticized by those who fear an evolution of liberal democracies to Post-democracy, and other who points out the high number of illiberal democracies.

Theory

Aristotle

Aristotle contrasted rule by the many (democracy/polity), with rule by the few (oligarchy/aristocracy), and with rule by a single person (tyranny/monarchy or today autocracy). He also thought that there was a good and a bad variant of each system (he considered democracy to be the degenerate counterpart to polity).[42][43]

Conceptions

Among political theorists, there are many contending conceptions of democracy.

- Aggregative democracy uses democratic processes to solicit citizens’ preferences and then aggregate them together to determine what social policies society should adopt. Therefore, proponents of this view hold that democratic participation should primarily focus on voting, where the policy with the most votes gets implemented. There are different variants of this:

- Under minimalism, democracy is a system of government in which citizens give teams of political leaders the right to rule in periodic elections. According to this minimalist conception, citizens cannot and should not “rule” because, for example, on most issues, most of the time, they have no clear views or their views are not well-founded. Joseph Schumpeter articulated this view most famously in his book Capitalism, Socialism, and Democracy.[44] Contemporary proponents of minimalism include William H. Riker, Adam Przeworski, Richard Posner.

- Direct democracy, on the other hand, holds that citizens should participate directly, not through their representatives, in making laws and policies. Proponents of direct democracy offer varied reasons to support this view. Political activity can be valuable in itself, it socializes and educates citizens, and popular participation can check powerful elites. Most importantly, citizens do not really rule themselves unless they directly decide laws and policies.

- Governments will tend to produce laws and policies that are close to the views of the median voter — with half to his left and the other half to his right. This is not actually a desirable outcome as it represents the action of self-interested and somewhat unaccountable political elites competing for votes. Downs suggests that ideological political parties are necessary to act as a mediating broker between individual and governments.Anthony Downs laid out this view in his 1957 book An Economic Theory of Democracy.[45]

- Robert A. Dahl argues that the fundamental democratic principle is that, when it comes to binding collective decisions, each person in a political community is entitled to have his/her interests be given equal consideration (not necessarily that all people are equally satisfied by the collective decision). He uses the term polyarchy to refer to societies in which there exists a certain set of institutions and procedures which are perceived as leading to such democracy. First and foremost among these institutions is the regular occurrence of free and open elections which are used to select representatives who then manage all or most of the public policy of the society. However, these polyarchic procedures may not create a full democracy if, for example, poverty prevents political participation.[46] Some see a problem with the wealthy having more influence and therefore argue for reforms like campaign finance reform. Some may see it as a problem that the majority of the voters decide policy, as opposed to majority rule of the entire population. This can be used as an argument for making political participation mandatory, like compulsory voting or for making it more patient (non-compulsory) by simply refusing power to the government until the full majority feels inclined to speak their minds.

- Deliberative democracy is based on the notion that democracy is government by discussion. Deliberative democrats contend that laws and policies should be based upon reasons that all citizens can accept. The political arena should be one in which leaders and citizens make arguments, listen, and change their minds.

- Radical democracy is based on the idea that there are hierarchical and oppressive power relations that exist in society. Democracy's role is to make visible and challenge those relations by allowing for difference, dissent and antagonisms in decision making processes.

Democracy and republic

Constitutional monarchs and upper chambers

Initially after the American and French revolutions the question was open whether a democracy, in order to restrain unchecked majority rule, should have an elitist upper chamber, the members perhaps appointed meritorious experts or having lifetime tenures, or should have a constitutional monarch with limited but real powers. Some countries (as Britain, the Netherlands, Belgium, Scandinavian countries and Japan) turned powerful monarchs into constitutional monarchs with limited or, often gradually, merely symbolic roles. Often the monarchy was abolished along with the aristocratic system (as in the U.S., France, China, Russia, Germany, Austria, Hungary, Italy, Greece and Egypt). Many nations had elite upper houses of legislatures which often had lifetime tenure, but eventually these senates lost power (as in Britain) or else became elective and remained powerful (as in the United States).

Supranational democracy

Qualified majority voting (QMV) is designed by the Treaty of Rome to be the principal method of reaching decisions in the European Council of Ministers. This system allocates votes to member states in part according to their population, but heavily weighted in favour of the smaller states. This might be seen as a form of representative democracy, but representatives to the Council might be appointed rather than directly elected. Some might consider the "individuals" being democratically represented to be states rather than people, as with many other international organizations.

European Parliament members are democratically directly elected on the basis of universal suffrage, may be seen as an example of a supranational democratic institution.

Non-government democracy

Aside from the public sphere, similar democratic principles and mechanisms of voting and representation have been used to govern other kinds of communities and organizations.

- Many non-governmental organisations decide policy and leadership by voting.

- Most trade unions choose their leadership through democratic elections.

- Cooperatives are enterprises owned and democratically controlled by their customers or workers.

Quotes

- Democracy...is government by discussion.

- Democracy is a system ensuring that the people are governed no better than they deserve.

- Democracy is the government of the people, by the people and for the people.

- The strongest argument against democracy is a five minute discussion with the average voter.

- -Sir Winston Churchill

- Democracy is the worst form of government, except all the others that have been tried.

- -Sir Winston Churchill

- Democracy is the best revenge.

- In the case of a word like DEMOCRACY, not only is there no agreed definition, but the attempt to make one is resisted from all sides. It is almost universally felt that when we call a country democratic we are praising it: consequently the defenders of every kind of régime claim that it is a democracy, and fear that they might have to stop using the word if it were tied down to any one meaning. Words of this kind are often used in a consciously dishonest way. That is, the person who uses them has his own private definition, but allows his hearer to think he means something quite different.[47]

- The twentieth century has been characterized by three developments of great political importance: the growth of democracy, the growth of corporate power, and the growth of corporate propaganda as a means of protecting corporate power against democracy.

See also

- List of types of democracy

- Democracy Index

- Democratic Peace Theory

- Democratization

- direct democracy

- E-democracy

- Election

- Foucault/Habermas debate

- Freedom deficit

- Freedom House, Freedom in the World report

- liberal democracy

- Majority rule

- Media democracy

- Netocracy

- Poll

- polyarchy

- Sociocracy

- sortition

- Voting

Notes

The United Nations has declared 15 September as the International Day of Democracy.[48]

References

- ^ Liberty and justice for some at Economist.com

- ^ Weatherford, J. McIver (1988). Indian givers: how the Indians of the America transformed the world. New York: Fawcett Columbine. pp. 117–150. ISBN 0-449-90496-2.

- ^ "The Global Trend" chart on Freedom in the World 2007: Freedom Stagnation Amid Pushback Against Democracy published by Freedom House

- ^ Democracy:Britannica Student Encyclopedia

- ^ Inoguchi, Takashi, Edward Newman, John Keane (1998). The Changing Nature of Democracy Page 255. United Nations University Press,

- ^ Democracy:Britannica Student Encyclopedia

- ^ Keen, Benjamin, A History of Latin America. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1980.

- ^ Kuykendall, Ralph, Hawaii: A History. New York: Prentice Hall, 1948.

- ^ Mahan, Alfred Thayer, "The United States Looking Outward," in The Interest of America in Sea Power. New York: Harper & Bros., 1897.

- ^ Brown, Charles H., The Correspondents' War. New York: Charles Scribners' Sons, 1967.

- ^ Taussig, Capt. J. K., "Experiences during the Boxer Rebellion," in Quarterdeck and Fo'c'sle. Chicago: Rand McNally & Company, 1963

- ^ Hegemony Or Survival, Noam Chomsky Black Rose Books ISBN 0-8050-7400-7

- ^ Deterring Democracy, Noam Chomsky Black Rose Books ISBN 0374523495

- ^ Class Warfare, Noam Chomsky Black Rose Books ISBN 1-5675-1092-2

- ^ Article on direct democracy by Imraan Buccus

- ^ Pierre-Joseph Proudhon. General Idea of the Revolution See also commentary by Graham, Robert. The General Idea of Proudhon's Revolution

- ^ Bookchin, Murray. Communalism: The Democratic Dimensions of Social Anarchism. Anarchism, Marxism and the Future of the Left: Interviews and Essays, 1993-1998, AK Press 1999, p. 155

- ^ Bookchin, Murray. Social Anarchism or Lifestyle Anarchism: An Unbridgeable Chasm

- ^ Graeber, David and Grubacic, Andrej. Anarchism, Or The Revolutionary Movement Of The Twenty-first Century

- ^ Iroquois Contributions to Modern Democracy and Communism. Bagley, Carol L.; Ruckman, Jo Ann. American Indian Culture and Research Journal, v7 n2 p53-72 1983

- ^ Iroquois Contributions to Modern Democracy and Communism. Bagley, Carol L.; Ruckman, Jo Ann. American Indian Culture and Research Journal, v7 n2 p53-72 1983

- ^ a b Native American Societies and the Evolution of Democracy in America, 1600-1800 Bruce E. Johansen Ethnohistory, Vol. 37, No. 3 (Summer, 1990), pp. 279-290

- ^ Political Theory and the Rights of Indigenous Peoples By Duncan Ivison, Paul Patton, Will Sanders. Page 237

- ^ Casper, Gretchen, and Claudiu Tufis. 2003. "Correlation Versus Interchangeability: the Limited Robustness of Empirical Finding on Democracy Using Highly Correlated Data Sets." Political Analysis 11: 196-203

- ^ freedomhouse.org: Methodology

- ^ Democracy in Ancient India. Steve Muhlberger, Associate Professor of History, Nipissing University.

- ^ Political Analysis in Plato's Republic at the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy

- ^ Aristotle Book 6

- ^ http://www.bbc.co.uk/history/ancient/greeks/greekdemocracy_01.shtml

- ^ ANCIENT ROME FROM THE EARLIEST TIMES DOWN TO 476 A.D

- ^ Activity Four

- ^ Omdirigeringsmeddelande

- ^ "Melanesia Historical and Geographical: the Solomon Islands and the New Hebrides", Southern Cross n°1, London: 1950

- ^ a b The National Archives | Exhibitions & Learning online | Citizenship | Struggle for democracy

- ^ The National Archives | Exhibitions & Learning online | Citizenship | Rise of Parliament

- ^ Jacqueline Newmyer, "Present from the start: John Adams and America", Oxonian Review of Books, 2005, vol 4 issue 2

- ^ Ray Allen Billington, America's Frontier Heritage (1974) 117-158. ISBN 0826303102

- ^ The French Revolution II

- ^ AGE OF DICTATORS: TOTALITARIANISM IN THE INTER-WAR PERIOD

- ^ [1]

- ^ freedomhouse.org: Tables and Charts

- ^ Aristotle, The Politics

- ^ Aristotle (384-322 BCE): General Introduction [Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy]

- ^ Joseph Schumpeter, (1950). Capitalism, Socialism, and Democracy. Harper Perennial. ISBN 0-06-133008-6.

- ^ Anthony Downs, (1957). An Economic Theory of Democracy. Harpercollins College. ISBN 0-06-041750-1.

- ^ Dahl, Robert, (1989). Democracy and its Critics. New Haven: Yale University Press. ISBN 0300049382

- ^ Politics and the English Language http://www.george-orwell.org/Politics_and_the_English_Language/0.html

- ^ GENERAL ASSEMBLY DECLARES 15 SEPTEMBER INTERNATIONAL DAY OF DEMOCRACY; ALSO ELECTS 18 MEMBERS TO ECONOMIC AND SOCIAL COUNCIL

Further reading

- Appleby, Joyce, Liberalism and Republicanism in the Historical Imagination (1992)

- Becker, Peter, Juergen Heideking and James A. Henretta, eds. Republicanism and Liberalism in America and the German States, 1750-1850. Cambridge University Press. 2002.

- Benhabib, Seyla, ed., Democracy and Difference: Contesting the Boundaries of the Political (Princeton University Press, 1996)

- Charles Blattberg, From Pluralist to Patriotic Politics: Putting Practice First, Oxford University Press, 2000, ch. 5. ISBN 0-19-829688-6

- Birch, Anthony H., The Concepts and Theories of Modern Democracy, (London: Routledge, 1993)

- Castiglione, Dario. "Republicanism and its Legacy," European Journal of Political Theory (2005) v 4 #4 pp 453-65.online version

- Copp, David, Jean Hampton, and John E. Roemer, eds. The Idea of Democracy Cambridge University Press (1993)

- Caputo, Nicholas America's Bible of Democracy, SterlingHouse Publisher, Inc. (ISBN 1-58501-092-8)

- Dahl, Robert A. Democracy and its Critics, Yale University Press (1989)

- Dahl, Robert A. On Democracy Yale University Press (2000)

- Dahl, Robert A. Ian Shapiro, and Jose Antonio Cheibub, eds, The Democracy Sourcebook MIT Press (2003)

- Dahl, Robert A. A Preface to Democratic Theory, University of Chicago Press (1956)

- Davenport, Christian. State Repression and the Domestic Democratic Peace Cambridge University Press (2007) ISBN 9780521864909

- Diamond, Larry and Marc Plattner, The Global Resurgence of Democracy, 2nd edition Johns Hopkins University Press, 1996

- Diamond, Larry and Richard Gunther, eds. Political Parties and Democracy (2001)

- Diamond, Larry and Leonardo Morlino, eds. Assessing the Quality of Democracy (2005)

- Diamond, Larry, Marc F. Plattner, and Philip J. Costopoulos, eds. World Religions and Democracy (2005)

- Diamond, Larry, Marc F. Plattner, and Daniel Brumberg, eds. Islam and Democracy in the Middle East (2003)

- Elster, Jon (ed.). Deliberative Democracy Cambridge University Press (1997)

- Fotopoulos, Takis, "Liberal and Socialist “Democracies” versus Inclusive Democracy", The International Journal Of Inclusive Democracy, Vol.2 No.2 (January 2006)

- Fotopoulos, Takis, "Direct and Economic Democracy in Ancient Athens and its Significance Today", Democracy & Nature, Vol.1 No.1 (Issue 1), 1992

- Gabardi, Wayne. "Contemporary Models of Democracy," Polity 33#4 (2001) pp 547+.

- Griswold, Daniel, Trade, Democracy and Peace: The Virtuous Cycle

- Hansen, Mogens Herman, The Athenian Democracy in the Age of Demosthenes, (Oxford: Blackwell, 1991)

- Held, David. Models of Democracy Stanford University Press, (1996), reviews the major interpretations

- Inglehart, Ronald. Modernization and Postmodernization. Cultural, Economic, and Political Change in 43 Societies Princeton University Press. 1997.

- Khan, L. Ali, A Theory of Universal Democracy. Martinus Nijhoff Publishers(2003)

- Hans Köchler ed., The Crisis of Representative Democracy, (Frankfurt a. M./Bern/New York: Peter Lang, 1987) (ISBN 3-8204-8843-X)

- Lijphart, Arend. Patterns of Democracy. Government Forms and Performance in Thirty-Six Countries Yale University Press (1999)

- Lipset, Seymour Martin. “Some Social Requisites of Democracy: Economic Development and Political Legitimacy”, American Political Science Review, (1959) 53 (1): 69-105. online at JSTOR

- Macpherson, C. B. The Life and Times of Liberal Democracy. Oxford University Press (1977)

- Morgan, Edmund. Inventing the People: The Rise of Popular Sovereignty in England and America (1989)

- Plattner, Marc F. and Aleksander Smolar, eds. Globalization, Power, and Democracy (2000)

- Plattner, Marc F. and João Carlos Espada, eds. The Democratic Invention (2000)

- Putnam, Robert. Making Democracy Work Princeton University Press. (1993)

- Raaflaub, Kurt A.; Ober, Josiah; Wallace, Robert W. Origins of democracy in ancient Greece. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2007 (hardcover, ISBN 0520245628).

- Riker, William H., The Theory of Political Coalitions (1962)

- Sen, Amartya K. “Democracy as a Universal Value”, Journal of Democracy (1999) 10 (3): 3-17.

- Tannsjo, Torbjorn. Global Democracy: The Case for a World Government (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2008), argues that not only is world government necessary if we want to deal successfully with global problems it is also, pace Kant and Rawls, desirable in its own right.

- Weingast, Barry. “The Political Foundations of the Rule of Law and Democracy”, American Political Science Review, (1997) 91 (2): 245-263. online at JSTOR

- Whitehead, Laurence ed. Emerging Market Democracies: East Asia and Latin America (2002)

- Wood, E.M., Democracy Against Capitalism, (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1995)

- Wood, Gordon S. The Radicalism of the American Revolution (1993), examines democratic dimensions of republicanism

External links

- Template:Dmoz

- Democracy at the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy

- Dictionary of the History of Ideas: Democracy

- The Economist Intelligence Unit’s index of democracy

- Democracy Watch (International) — Worldwide democracy monitoring organization.

- Critique

- Hans-Hermann Hoppe, Democracy, The God That Failed, (Rutgers, NJ: 2001). Discussion by the author

- Erik von Kuehnelt-Leddihn, Liberty or Equality

- J.K. Baltzersen, Churchill on Democracy Revisited, (24 January 2005)