Middle Eastern theatre of World War I

| Middle Eastern theatre | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of World War I | |||||||||

| File:WW1 TitlePicture For Middle Eastern theatre.png Clockwise from top: April 1915, city of Van in Van Province, Ottoman Empire; Mustafa Kemal at the trenches in the Gallipoli; Ottoman seaplane; Machine gun crew at the Sarikamish | |||||||||

| |||||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||||

|

|

| ||||||||

| Strength | |||||||||

|

Total conscripted: 2,850,000 max strength: 800,000 | |||||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||||

|

KIA:771,844[3] | |||||||||

| The breakdown of Ottoman casualties is listed under Ottoman casualties of World War I | |||||||||

The Middle Eastern theatre of World War I (November 2, 1914 - October 29, 1918) fought between mainly the Ottoman Empire of the Central Powers and primarily of the British and the Russians of the Allied Powers with the Arabs who participated in the Arab Revolt, the Armenians initially with Armenian Resistance extending to the Armenian Corps of Democratic Republic of Armenia. This theatre encompassed the largest territory of all the theatres of WWI. It comprised five main campaigns: the Sinai and Palestine Campaign, the Mesopotamian Campaign, the Caucasus Campaign, the Persian Campaign and the Gallipoli Campaign. There were also minor operations of Arabia and Southern Arabia Campaign, and Aden Campaign. Besides the regular forces both sides used the asymmetrical forces in the region. The theater ended with the Russians after the Armistice of Erzincan (December 5, 1917) resulting with the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk (March 3, 1918), with Armenians after the Trabzon Peace Conference (March 14 - April 5 1918) resulting with the Treaty of Batum (June 4 1918) and with rest of the Allied Powers after the Armistice of Mudros (October 30, 1918) resulting with the Treaty of Sèvres (August 10, 1920).

Objectives

The Ottoman Empire joined the Central Powers in October–November 1914, pursuant to the secret Ottoman-German Alliance[4] signed on August 2, 1914, threatening Russia's Caucasian territories and Britain's communications with India and the East via the Suez Canal. The main objective of the Ottoman Empire at the Caucuses was the recovery of its territories in Eastern Anatolia lost during the prior Russo-Turkish War, 1877-78. The military goals of the Caucasus Campaign was determined to retake Artvin, Ardahan, Kars, and the port of Batum.

A success in this region would mean a diversion of Russian forces to this front from the Polish and Galician fronts.[5] The plan found sympathy with German advisory. From economic perspective, the Ottoman — or rather German — strategic goal was to cut off Russian access to the hydrocarbon resources around the Caspian Sea.[6] Germany established Intelligence Bureau for the East on the eve of World War I. The bureau was involved in intelligence and subversive missions to Persia and to Afghanistan, to dismantle the Anglo-Russian Entente.[7]

Aligned with the Germany, Ottoman Empire wanted to wane the influence of the Entente in the Persia. Ottoman War Minister Enver Pasha claimed that if Russians could be beaten in the key cities of Persia, it could open the way to Azerbaijan, to Central Asia and to India. If these nations were to be removed from western influence, Enver visioned a cooperation between these newly establishing Turkic states. This was the main philosophy of the newly flourishing nationalistic pan-Turkic movement, creation of a single country, Turan for all Turkish-speaking people. Enver's project conflicted a major western project played out as struggles among several key imperial powers (Enver was a devout Muslim and anti-imperialistic in his thinking), known as Imperialism in Asia. His political position was based on the assumption [which turned to be true] none of the colonial powers possessed the resources to withstand the strains of world war and maintain their direct rule in Asian states [Enver concentrated on a smaller geopolitical section limited in Turkic nature]. Although nationalist movements throughout the colonial world led to the political independence of nearly all of the Asia's remaining colonies during World War One and interwar period, but decolonisation on the scale of Enver's ambitions was never achieved. However, Enver continued with his ambition after the partitioning of the Ottoman Empire by the powerful Imperial Powers until his death on a battle field fighting Russians on August 4, 1922.

In 1914, before the war, the British government had contracted with the Anglo-Persian Oil Company for the supply of oil-fuel for the navy.[6] The Anglo-Persian Oil Company was in the proposed path of Enver's project which British had the exclusive rights to work petroleum deposits throughout the Persian Empire except in the provinces of Azerbaijan, Ghilan, Mazendaran, Asdrabad and Khorasan.[6]

Russia viewed the Caucasus Front as secondary to the Eastern Front. Russia had taken the fortress of Kars from the Turks during the Russo-Turkish War in 1877 and feared a campaign into the Caucasus aimed at retaking Kars and the port of Batum. In March 1915, when the Russian foreign minister Sergey Sazonov meet with British ambassador George Buchanan and French Ambassador Maurice Paléologue stated that a lasting postwar settlement demanded full Russian possession of the capital city of the Ottoman Empire, the straits of Bosphorus and Dardanelles, the Sea of Marmara, southern Thrace up to the Enos-Midia line as well as parts of the Black Sea coast of Anatolia between the Bosphorus, the Sakarya River and an undetermined point near the Bay of Izmit. The Russian Tsarist regime planned to replace the Muslim population of Northern Anatolia and Istanbul with more reliable Cossack settlers [8]

Armenian national liberation movement also sought to establish First Republic of Armenia in the Eastern part of Asia Minor. The Armenian Revolutionary Federation achieved this goal while the Ottoman rule was finally crumbling, with the establishment of the internationally recognized Democratic Republic of Armenia in May 1918. Also as early as 1915, the Administration for Western Armenia and later Republic of Mountainous Armenia were Armenian controlled entities, while Centrocaspian Dictatorship was established with Armenian participation. None of these entities were long lasting.

Forces

After the Young Turk Revolution and the establishment of the Second Constitutional Era ([İkinci Meşrûtiyet Devri] Error: {{Lang-xx}}: text has italic markup (help)) on July 3, 1908, a major military reform initiative started. Army headquarters were modernized. The Ottoman Empire engaged with the Turco-Italian War and Balkan Wars just short of couple years before which forced more restructuring of the army. During this period, the empire divided its forces into armies. Each army headquarters consisted of a chief of staff and operations section, intelligence section, logistics section and a personnel section. As a long established tradition in Ottoman military, support departments for supplies, medical and veterinary services included in these armies. In 1914, before Ottoman Empire entered the War, the four Armies divided their forces into Corps and Corps into divisions such that each division had 3 infantry regiments and an artillery regiment. Before the war, the largest units were First Army had 15 divisions in total; Second Army had 4 divisions in total; additionally, an independent infantry division with 3 infantry regiments and an artillery brigade; Third Army had 9 divisions in total. Additionally, four independent infantry regiments and four independent cavalry regiments (tribal units); Fourth Army had 4 divisions in total. In August 1914, of 36 infantry divisions organized, 14 were established from scratch and essentially new divisions. In a very short time, these 8 newly recruited divisions gone through major redeployment. During the World War, more armies established under the names of 5th Army, 6th Army in 1915 and 7th Army, 8th Army in 1917. Kuva-i İnzibatiye and just in the name Army of Islam which had only a single Corps in 1918. By 1918, these original armies had been so badly reduced that the Empire was forced to establish new unit definitions which incorporated from these armies. These were the “Army Groups” with the names of Orient Army Group and Thunderbolt Army Group. However, although the number of armies were increasing during this four years, its resources were declining, both in manpower and supplies, nothing much was left as Army Groups in 1918 were not bigger than Armies in 1914. Just about all the war equipment was built by Germans or Austrians and were maintained by German and Austrian engineers. In 1918, the Ottoman Army was still partially intact and partially effective to the end of the war.

Germany mainly supplied the military advisers to this theatre. The German Caucasus Expedition force was established by the German Empire to be used in the formerly Russian Transcaucasia around early 1918 during the Caucasus Campaign. Its prime aim was to secure oil supplies to Germany and stabilize a nascent pro-German Democratic Republic of Georgia, which brought the Ottoman Empire and Germany at odds including a hot conflict and exchange of official condemnations between them at the final months of the war.

Before the war, Russia had Russian Caucasus Army but they had to redeploy almost half of their forces to the Prussian front due to the defeats at the Battle of Tannenberg and the Masurian Lakes, leaving behind just 60,000 troops in this theatre. In the summer of 1914, Armenian volunteer units were established under the Russian Armed forces. Nearly 20,000 Armenian volunteers expressed their readiness to take up arms against the Ottoman Empire as early as 1914. In several towns occupied by the Russians the Armenian have shown themselves ready to join the Russian volunteer army.[9] The size of these units will increase during the war such that Boghos Nubar presented 150,000 as the summary of Armenian units in a public latter to the Paris Peace Conference, 1919.[10]

In 1914, British had British Indian Army units located in the southern influence zone at the Persian Campaign zone. These units had extensive experience in dealing with tribal forces because of the Indian experience. British later established Mediterranean Expeditionary Force, British Dardanelles Army, Egyptian Expeditionary Force and in 1917 they established Dunsterforce under Lionel Dunsterville to lead an Allied force of under 1,000 Australian, British, Canadian and New Zealand elite troops, accompanied by armored cars. Arab forces involved in numbered around 5,000 soldiers. This number included Arab Regulars who fought with Allenby's army, and not the irregular forces under the direction of Lawrence and Feisal. There is no officially presented size of irregular forces engaged in asymmetrical conflicts.

France sent the French Armenian Legion to this theatre as part of its larger French Foreign Legion. Foreign Minister Aristide Briand needed to provide troops for French commitment made in Sykes-Picot Agreement, which was still secret. [11]. Armenian leadership, the leader of Armenian national assembly Boghos Nubar, also meet with Sir Mark Sykes and Georges-Picot after signing French-Armenian Agreement. The Armenian support was planned under command of General Edmund Allenby, however extend to original agreement, Armenian legion fought in Palestine and Syria. Many of the volunteers in Foreign Legion who managed to survive the first years of the war were generally released from the Legion to join their respective national armies.

Armenian national liberation movement commanded the Armenian Fedayee (Armenian: Ֆէտայի) during these conflicts. These were generally refereed as Armenian partisian guerrilla detachments. In 1917, The Dashnaks established Armenian Corps under the command of General Tovmas Nazarbekian which with the declaration of the Democratic Republic of Armenia became the military core of this new Armenian state and Nazarbekian became the first Commander-in-chief.

Recruitment

The Ottoman Empire established a new recruitment law on 12 May 1914. This new law lowered the conscription age from 20 to 18 and abolished the “redif” or reserve system. Active duty lengths were set at 2 years for the infantry, 3 years for other branches of the Army and 5 years for the Navy. These measures remained largely theoretical during the war. Traditional Ottoman forces depended on volunteers from the Muslim population of the empire. Additionally, several groups and individuals in the Ottoman society volunteered for active duty during the World War. The major examples being the “Mevlevi” and the “Kadiri.” There were also units formed by Caucasain and Rumelian Turks, who took part in the battles in Mesopotamia and Palestine. Among Ottoman forces volunteers were not only from Turkic groups; there were also Arab and Bedouin volunteers who supported the campaign against the British to capture the Suez Canal, and in Mesopotamia. It has to be noted that these forces did not provide a substantial support. Volunteers become unreliable with the establishment of organized army, as they were not trained well, also most of the Arab and Bedouin volunteers were motivated by financial gains. As the real conflicts approached, Ottoman volunteer system disappeared by itself.

Before the war, Russia established a volunteer system to be used in the Caucasus Campaign. In the summer of 1914, Armenian volunteer units were established under the Russian Armed forces. As the Russian Armenian conscripts were already send to the European Front, this force was uniquely established from Armenians that were not Russian Armenian or the ones that were not obligated to serve. The Armenian detachment units were credited no small measure of the success which attended by the Russian forces, as they were natives of the region, adjusted to the climatic conditions, familiar with every road and mountain path, and had real incentive to fierce and resolute combat.[12] The Armenian volunteers were small, mobile, and well adapted to the semi-guerrilla warfare.[13] They did good work as scouts, though they took part in many severe engagements.[13]

Asymmetrical forces

The forces used in the Middle Eastern theatre was not only regular army units and regular warfare, but also what is known today as "Asymmetrical conflicts".

Contrary to myth, it was not T. E. Lawrence or the Army that conceptualised a campaign of internal insurgency against the Ottoman Empire in the Middle East: it was the Arab Bureau of Britain's Foreign Office that devised the Arab Revolt. The Arab Bureau had long felt it likely that a campaign instigated and financed by outside powers, supporting the breakaway-minded tribes and regional challengers to the Ottoman government's centralised rule of their empire, would pay great dividends in the diversion of effort that would be needed to meet such a challenge. The Ottoman authorities devoted a hundred or a thousand times the resources to contain the threat of such an internal rebellion compared to the Allies' cost of sponsoring it.

Germany established Intelligence Bureau for the East on the eve of War. It was dedicated to promoting and sustaining subversive and nationalist agitations in the British Indian Empire and the Persian Campaign and Egyptian satellite states. Its Persia operations were led by Wilhelm Wassmuss.[14] Wilhelm Wassmuss was a German diplomat, also known as the "German Lawrence of Arabia or "Wassmuss of Persia". He attempted to foment trouble for the British in the Persian Gulf.

Operational Area

The Caucasus Campaign extended from the Caucasus to the Eastern Anatolia reaching as far as Trabzon, Bitlis, Muş and Van. The land warfare was accompanied by the Russian navy in the Black Sea Region. The Persian Campaign was at northern Persian Azerbaijan and western Persia compromising the provinces of East Azarbaijan, West Azarbaijan and Ardabil cities included Tabriz, Urmia, Ardabil, Maragheh, Marand, Mahabad and Khoy. The Gallipoli Campaign took place at Gallipoli peninsula. The Mesopotamian campaign was limited to the lands watered by the rivers Euphrates and Tigris cities included Basra Kut, Baghdad. The main challenge at this operational area was moving the supplies and troops through the swamps (Mesopotamian Marshes) and deserts which surrounded the conflict area. The Sinai and Palestine Campaign took place on the Sinai Peninsula, Palestine, and Syria, cities included Gaza, Jerusalem.

General consensus is that Ottoman Empire mainly fought on the Empire’s own territories. In reality over 90,000 close to 100,000 troops were sent to the Eastern European Front in 1916. The operations in Romania at the Balkans Campaign is not part of this article. Central Powers asked these units to support the operations against the Russian army. Later, concluded that was a big military mistake. These forces were needed to protect the Ottoman territory as the massive Erzerum Offensive was under way. This move, initiated by Enver’s proposal, originally rejected by the German Chief of Staff General Falkenhayn, but later his successor, Hindenburg, agreed, however with some doubts. The decision was reached after the Brusilov Offensive, as the Central Powers had a big manpower gap in the Eastern Power. Beginning with early 1916, Enver decided to send XV Army Corps to Galicia, VI Army Corps to Romania, XX Army Corps and 177th Infantry Regiment to Macedonia. There are two Turkish sources regarding these operations and respectively they state 117,000 and 130,000 send but both agree that nearly 8,000 of them were KIA with another 22,000 being WIA.

Support Zones

Ottoman Empire hoping to develop distraction to the British in Sinai and Palestine Campaign engaged at the neighboring North African Campaign of the African theatre of World War I. Ottoman Empire had a continued military existence since the Italo-Turkish War of 1911-1912. Enver Pasha supported the nucleus of the resistance in Libya to the Italian colonial regime because of the natural connection between them as a result of Islam in Libya. The rise of Libyan nationalism fostered with this unified resistance to the Italians. Sanusi influence was strongest in Cyrenaica. Sanusi rescued the region from unrest and anarchy, as the Sanusi movement gave the Cyrenaican tribal people an attachment and feelings of unity and purpose. Early 1915, Italy and Ottoman Empire was not in war. In support of Sanusi, only 500 Ottoman officers and soldiers fought at this front in leading Sanusi militia, which numbered between 15,000 and 30,000 according to Turkish and Italian sources. At the beginning of the war, the Sanusi militia was well trained force under the Ottoman officers of the secret service Teşkilat-ı Mahsusa. When Italy declared war on Central Powers on 24 May 1915, the Italian-Sanusi war became a part of the War and the Ottoman General Staff sent advisers and arms to Ahmad al-Sharif instead of using secret service. Ahmad al-Sharif was leading the struggle with the title of “Amir-al-Muminin” for Africa. In addition, German and Ottoman agents encouraged rebellions against the Allies in Libya and Morocco (which had been annexed by France in 1912) and these regions were barely controlled when war broke out in Europe, providing light weapons via U-Boats sailing from Empire's shores and Austria-Hungary or through neutral countries like Spain. The Senussi sect was particularly successful in the Sahara, expelling the Italians from Fezzan and tying British and French forces in the frontier regions of Egypt and Algeria. Ottoman soldiers continued to stay in the region until the early months of 1919. Berber revolts in Morocco and Libya would continue well after the end of the war, till their final suppression in the late 1920s, by Rodolfo Graziani who commanded the Italian forces in pacifying the Senussi. During this "pacification" tens of thousands Libyan prisoners (Sasuni) died.[15] When the WWI was over, Libya was officially removed from Ottoman control.

Chronology

Prelude

Early July 1914, The political situation had changed dramatically after the events in Europe. Ottoman Empire forced to have a secret Ottoman-German Alliance on 2 August 1914, followed by another treaty with Bulgaria. Ottoman War ministry developed two major plans. Bronsart von Schellendorf began to revise a plan and completed it on 6 September 1914. Accordingly, the Fourth Army was to attack Egypt, whereas the Third Army would launch an offensive against the Russians in Eastern Anatolia. In the Ottoman Army there was a dissident to Schellendorf. The most voiced opinion was Schellendorf planned a war which benefited the German operations rather than taking account the conditions of the Ottoman Empire. Hafız Hakkı presented the second campaign plan. This plan was much more aggressive, but took the conflicts to opposing side. This plan concentrated on Russia, and based on forces to be shipped to the eastern Black Sea coast, where they would develop an offensive against Russians. Hafız Hakkı’s plan shelved because the Ottoman Army had not enough resources. Schellendorf plan which was fought in the Ottoman territory had direct consequences to Empire's own people. Schellendorf’s "Primary Campaign Plan" became the dominant choice. It was proven later that his plan also challenged with lack of resources, but he had a better concentration plan for organizing the command and control of the army and positioning it to execute the plans, also a better mobilization plan for generating forces and preparing them for war. Among some historical documents within the Ottoman War minister's archives today are the War plans drafted by General Bronsart von Schellendorf, dated 7 October 1914, included Ottoman support to the Bulgarian army, a secret operation on Romania and Ottoman soldier's landing in Odessa and Crimea with the support of German Navy. One unique characteristic for the Palestine campaign was until the defeat in Palestine and later Mustafa Kemal’s appointment as the commander of the Seventh Army, most of the staff posts in the Yıldırım Army Group were held by German officers which their influence was so great that even the correspondence within the headquarters was done in German language though there was no German soldiers on the front lines of the battle fields.

During July 1914, there were negotiations between the Committee of Union and Progress (CUP) and Armenians at the Armenian congress at Erzurum. The public conclusion of this congress was "Ostensibly conducted to peaceful advance Armenian demands by legitimate means".[16] The CUP regarded the congress as the seedbed for establishing the decision of insurrection.[17] Historian Erikson concluded that after this meeting the CUP was convinced on strong Armenian — Russian links with detailed plans aimed at the detachment of the region from the Ottoman Empire.[17]

On October 29, 1914, The Ottoman Empire's engagement with the first armed conflict with Allies occurred when German battlecruiser Goeben and light cruiser Breslau, operating under Ottoman flag shelled the Russian Black Sea port of Odessa, after the Pursuit of Goeben and Breslau.

1914

Mesopotamian Campaign: On November 6 1914, the British offensive began with the naval force bombarding the old fort at Fao. The Fao Landing of British Indian Expeditionary Force D (IEF D) comprising the 6th (Poona) Division led by Lieutenant General Arthur Barrett, with Sir Percy Cox as Political Officer was opposed by 350 Ottoman troops and 4 cannons. On November 22, the British occupied the city of Basra against a force of 2900 Arab conscripts of the Iraq Area Command commanded by Suphi Pasha. Suphi Pasha and 1,200 prisoners were captured by the British. The main Ottoman army, under the overall command of Khalil Pasha was located 275 miles north-west around Baghdad. They made only weak efforts to dislodge the British.

Caucasus Campaign: On November 1, the Bergmann Offensive was the first armed conflict of this front. The Russians crossed the Russo-Turkish frontier first, and planned to capture Doğubeyazıt and Köprüköy.[18] Russians had two wings. On the right wing, the Russian I Corps crossed the border and moved from Sarıkamış toward the direction of Köprüköy. On the left wing, the Russian IV Corps moved from Yerevan to Pasinler Plains. The commander of 3rd Army, Hasan Izzet was not in favor of an offensive action in the harsh winter conditions. His plan to remain in defense to launch a counter attack at the right time was overridden by the War Minister Enver Pasha. On November 7, the 3rd Army commenced its offensive with the participation of the XI Corps and all cavalry units supported by Kurdish Tribal Regiment. By 12 November, Ahmet Fevzi Pasha's the IX Corps reinforced with the XI Corps on the left flank supported with the cavalry began to push the Russians back. The Russian success was along the southern shoulders of the offensive where Armenian volunteers were effective and took Karaköse and Doğubeyazıt.[19] By the end of November, the Russians hold to a salient 25 kilometres into Ottoman territory along the Erzurum-Sarıkamış axis. On December 22, 3rd Army received the order to advance towards Kars, which will be the Battle of Sarikamish. In the face of the 3rd Army's advance Governor Vorontsov planned to pull the Russian Caucasus Army back to Kars. Yudenich ignored Vorontsov's order. Enver Pasha assumed the personal command of the 3rd Army and ordered the forces to move against the Russian troops.

Persian Campaign: In December 1914, at the height of the Battle of Sarikamish in the Caucasus Campaign, General Myshlaevsky ordered withdrawal of Russian forces to be used against the Enver's offense. Only one brigade of Russian troops under the command of the Armenian General Nazarbekoff and one battalion of Armenian volunteers scattered throughout Salmast and Urmia. While main Ottoman troops were preparing for the operation in Persia, a small Russian group crossed the Persian frontier. After repulsing a Russian offensive toward Van-Persia mountain crossings, Van Gendarmerie Division, a lightly equipped paramilitary formation commanded by Major Ferid, chased the enemy into Persia. On December 14 1914, Van Jandarma Division occupied the city of Kotur. Later, proceeded towards Hoy. It was supposed to keep this passage open to Kazım Bey (5th Expeditionary Force) and Halil Bey units (1th Expeditionary Force) who were to move towards Tabriz from the bridgehead established at Kotur. However, the Battle of Sarıkamısh depleted the Ottoman forces and these expeditionary forces needed elsewhere.

Gallipoli Campaign: In November, First Lord of the Admiralty Winston Churchill put forward his initial plans for a naval attack, based at least in part on what turned out to be erroneous reports regarding Ottoman troop strength, as prepared by Lieut. T. E. Lawrence. He reasoned that the Royal Navy had a large number of obsolete battleships might well be made useful supported by using a token forces from the army being required for routine occupation tasks. The battleships ordered to be ready by February 1916.

1915

Mesopotamian Campaign: Enver Pasha realized the mistake of underestimating the importance of the Mesopotamian campaign. On January 2, Süleyman Askeri Bey assumed the Iraq Area Command. The Ottoman Army did not have any other resources to move to this region as the Gallipoli Campaign was in the horizon. Süleyman Askeri Bey sent letters to Arab sheiks in an attempt to organize them to fight against the British. On January 3, at the battle of Qurna Ottoman forces tried to retake the city of Basra. They had been under fire from Royal Navy vessels on the Euphrates while British troops had managed cross the Tigris. Judging that the earthworks were too strong to be taken, the Ottomans surrendered the town of Al-Qurnah and retreated back to Kut. On April 12, Süleyman Askeri attacked the British camp at Shaiba with 3800 troops early in the morning. These forces provided by Arab sheiks did not produce any results. Süleyman Askeri was wounded at Shaiba. The disappointed and depressed Süleyman Askeri shot himself at the hospital in Baghdad. Due to the unexpected success British command reconsidered their plan in favor of aggressive operations. In April 1915, general Sir John Nixon was sent to take command. He ordered Charles Vere Ferrers Townshend to advance to Kut or even to Baghdad if possible. Enver Pasha worried about the possible fall of Baghdad. He sent German General Colmar von der Goltz to take the command. On 22 November, Townshend and von der Goltz fought a battle at Ctesiphon. The battle was inconclusive as both the Ottomans and the British ended up retreating from the battlefield. Brits halted and fortified the position at Kut-al-Amara. The rapid advance of the British up the river changed some of the Arab tribes perception of the conflict. There was already an initial Arab Revolt in the Sinai and Palestine Campaign. Realizing that the British had the upper-hand, Arabs in the region joined the British efforts. They raided Ottoman the military hospitals and massacred the soldiers in Amara. On December 7, the siege of Kut began. Von der Goltz helped the Ottoman forces build defensive positions around Kut. Brits established new fortified positions down river fended off any attempt to rescue Townshend. General Aylmer made three major attempts to break the siege, but each effort was unsuccessful.

Caucasus Campaign: In January, the battle of Sarikamish ended. Result was a stunning defeat for the Ottoman 3rd Army. Only 10% of the 3rd army managed to retreat back to its starting position. Enver gave up command of the 3rd army. During this conflict Armenian detachment units challenged the Ottoman operations at the critical times: "the delay enabled the Russian Caucasus Army to concentrate sufficient force around Sarikamish".[20] In February, General Yudenich promoted to command to Russian Caucasus Army replacing Aleksandr Zakharevich Myshlayevsky. On February 12, commander of the 3rd Army Hafız Hakkı died of typhus and replaced by Brigadier General Mahmut Kamil Paşa. Kamil took the task of putting the army in order which was depleted after Battle of Sarikamish. The British and France asked Russia to relieve the pressure on Western front. Russia needed time to organize it's forces. The operations in the Black Sea gave the chance to replenish Russian forces also the Battle of Gallipoli helped the Russian forces in this front to reorganize.[18] In March 1915, 3rd army received new blood by the reinforcements from the 1st and 2nd Armies although these supplements were no stronger than a division. On April 20, the Van Resistance brought the conflicts into city of Van. On April 24, Talat Pasha with the order on April 24 (known by the Armenians as the Red Sunday) claimed that the Armenians in this region organized under the leadership of Russians and rebelled against Ottoman government. On May 6, General Yudenich began an offensive into Ottoman territory. One wing of this offensive headed towards Lake Van to relieve the Armenian residents of the Van Resistance. The Fedayee turned over the city of Van. On May 21, General Yudenich received the keys to the city of Van, citadel of Van and confirmed the Armenian provisional government in office with Aram Manougian as governor. Fighting shifted farther west for the rest of the summer with Van secure.[5] On May 6, the Russian second wing advanced through the Tortum Valley towards Erzurum after weather conditions changed to milder. The Ottoman 29th and 30th Divisions managed to stop this assault. The X Corps counter-attacked the Russian forces. On the southern part, Ottomans were not as successful as they have been in the north. On 17 May, Russian forces at the city of Van continued to push back the Ottoman units. On May 11 city of Malazgirt had had already fallen. Ottomans supply lines were being cut, as the Armenian forces caused additional difficulties behind the lines. The region south of Lake Van was extremely vulnerable. During May, Ottoman's had to defend a line of more than 600 kilometers with only 50,000 men and 130 pieces of artillery. They were clearly outnumbered by the Russians. On May 27, during the high point of Russian offensive Ottoman parliament passed the Tehcir Law. The interior minister of Talat Pasha, ordered a forced deportation of all Armenians out of the region. The Armenian's of the Van Resistance and others which were under the Russian occupation were spared from these deportations. On June 19, the Russians launched another offensive. This time northwest of Lake Van. The Russians, under Oganovski, launched an offense into the hills west of Malazgrit. The Russians underestimated the size of the Ottoman forces in this region. They were surprised by a large Ottoman force at the Battle of Malazgirt. They were not aware of the fact that the Turkish IX Corps, together with the 17th and 28th Divisions was moving to Muş as well. 1st and 5th Expeditionary Forces were positioned to the south of the Russian offensive force and a “Right Wing Group” was established under the command of Brigadier General Abdülkerim Paşa. This group was independent from the Third Army and Abdülkerim Paşa was directly reporting to Enver Paşa. The Turks were ready to face the Russian attacks. On September 24, General Yudenich become the supreme commander of all Russian forces in the region. This front was quiet from October till the end of the year. Yudenich used this period to reorganize. At the turn of the 1916, Russian forces reached a level of 200,000 men and 380 pieces of artillery. On the other side the situation was very different; the Ottoman High Command failed to make up the losses during this period. The war in Gallipoli was sucking all the resources and manpower. The IX, X and XI Corps could not be reinforced and in addition to that the 1st and 5th Expeditionary Forces were deployed to Mesopotamia. Enver Pasha, after not achieving his ambitions or recognizing the dire situation on other fronts, decided that the region was of secondary importance.

Gallipoli Campaign: On 19 February, the first attack began when a strong Anglo-French task force, including the British battleship HMS Queen Elizabeth, bombarded artillery along the coast. Admiral Carden sent a cable to Churchill on 4 March, stating that the fleet could expect to arrive in Constantinople within fourteen days.[21] On 18 March the first major attack was launched. The fleet, comprising 18 battleships as well as an array of cruisers and destroyers, sought to target the narrowest point of the Dardanelles where the straits are just a mile wide. The French ship Bouvet exploded in mysterious circumstances, causing it to capsize with its entire crew aboard. Minesweepers, manned by civilians and under constant fire of Ottoman shells, retreated leaving the minefields largely intact. HMS Irresistible and HMS Inflexible both sustained critical damage from mines, although there was confusion during the battle whether torpedoes were to blame. HMS Ocean, sent to rescue the Irresistible, was itself struck by an explosion and both ships eventually sank. The French battleships Suffren and Gaulois were also badly damaged. The losses prompted the Allies to cease any further attempts to force the straits by naval power alone. On April 25, the second set of campaign, took place at on the Gallipoli Peninsula on the European side of the Dardanelles. The Allies decided to seize the European side of the Dardanelles with an amphibious assault. The troops were able to land but could not dislodge the Ottoman forces after months of battle that caused the deaths of an estimated 131,000 soldiers, and 262,000 wounded. Eventually the Allied forces withdrew. The campaigning represented something of a coming of age for Australia and New Zealand who celebrate April 25 as ANZAC Day. Kemal Ataturk, who would go on to become the first leader of modern Turkey distinguished himself as a Lieut. Colonel in the Ottoman forces there.

Sinai and Palestine Campaign: The Ottoman Empire tried to seize the Suez Canal in Egypt with the First Suez Offensive and they supported the recently deposed Abbas II of Egypt, but were pulled back by the British on both goals.

Arab Revolt: The British, based in Egypt, began to incite the Arabs living in Hejaz near the Red Sea and inland to revolt to expel the Ottoman forces from what is the modern-day Saudi Arabian peninsula.

1916

Arab Revolt: In 1916, a combination of diplomacy and genuine dislike of the new leaders of the Ottoman Empire (the Three Pashas) convinced Sherif Hussein ibn Ali of Mecca to begin a revolt. He gave the leadership of this revolt to two of his sons: Faisal and Abdullah, though the planning and direction for the war was largely the work of Lawrence of Arabia.

Caucasus Campaign: The Russian offensive in northeastern Turkey started with a victory at Battle of Koprukoy and culminated with the capture of Erzurum in February and Trabzon in April. By the Battle of Erzincan the Third Army was no longer capable of launching an offensive nor could it stop the advance of the Russian Army.

Sinai and Palestine Campaign: The Ottoman forces launched a second attack across the Sinai with the objective of destroying or capturing the Suez Canal. Both this and the earlier attack (1915) were unsuccessful, though not very costly by the standards of the Great War. The British then went on the offensive, attacking east into Palestine. However, two failed attempts to capture the Ottoman fort of Gaza resulted in sweeping changes to the British command and the arrival of General Allenby, along with many reinforcements.

1917

Mesopotamian Campaign: British Empire forces reorganized and captured Baghdad in March 1917.

Caucasus Campaign: On December 16, The Armistice of Erzincan (Erzincan Cease-fire Agreement) was signed which officially brought the end to the hostilities between Ottoman Empire and Russians. The Special Transcaucasian Committee also endorsed the agreement.

Arab Revolt: The Sinai and Palestine Campaign was dominated with the success of the revolt. The revolt aided the General Allenby's 1917's operations.

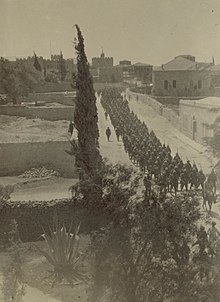

Sinai and Palestine Campaign: Late in 1917, Allenby's Egyptian Expeditionary Force smashed the Ottoman defenses and captured Gaza, and then captured Jerusalem just before Christmas. While strategically of minimal importance to the war, this event was key in the subsequent creation of Israel as a separate nation in 1948.

1918

Sinai and Palestine Campaign: The Ottoman Empire could be defeated with campaigns in Palestine and Mesopotamia and the Spring Offensive delayed the expected attack. General Allenby was given brand new divisions recruited from India. The British achieved complete control of the air. General Liman von Sanders had no clear idea where the British were going to attack. Compounding the problems, withdrew their best troops to Caucasus Campaign. General Allenby finally launched the Battle of Megiddo, with the Jewish Legion under his command. Ottoman troops started a full scale retreat.

Arab Revolt: T. E. Lawrence and his Arab fighters staged many hit-and-run attacks on supply lines and tied down thousands of soldiers in garrisons throughout Palestine, Jordan, and Syria.

Caucasus Campaign: On March 3, the Grand vizier Talat Pasha signed the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk with the Russian SFSR which stipulated that Bolshevik Russia cede Batum, Kars, and Ardahan to Ottoman Empire. The Trabzon Peace Conference held between March and April among the Ottoman Empire and the delegation of the Transcaucasian Diet (Transcaucasian Sejm) and government. Treaty of Brest-Litovsk united the Armenian-Georgian block[22]. Democratic Republic of Armenia declared the existence of a state of war between the Ottoman Empire[22]. In early May, 1918, the Ottoman army faced the Armenian Corps of Armenian National Councils which soon declared the Democratic Republic of Armenia. The Ottoman army captured Trabzon, Erzurum, Kars, Van, and Batumi. The conflict led to the Battle of Sardarapat, the Battle of Kara Killisse (1918), and the Battle of Bash Abaran. Although the Armenians managed to inflict a defeat on the Ottomans at the Battle of Sardarapat, the Ottoman army won the later battle and scattered the Armenian army. The fight with Democratic Republic of Armenia ended with the sign the Treaty of Batum in June, 1918. However throughout the summer of 1918, under the leadership of Andranik Toros Ozanian Armenians in the mountainous Karabag region resisted the Ottoman 3th army and established the Republic of Mountainous Armenia[23]. The Army of Islam avoided Georgia and marched to the Azerbaijan Democratic Republic. They got as far as Baku on the Caspian Sea. They threw the British out in September 1918 with the Battle of Baku.

Aftermath

On October 30 1918, The Armistice of Mudros, signed on aboard HMS Agamemnon in Mudros port on the island of Lemnos with the Ottoman Empire and Triple Entente. Ottoman activities at all the active campaigns terminated.

Military occupation

On November 13 1918, the Occupation of Constantinople (present day Istanbul) of the capital of the Ottoman Empire happened by the French troops followed by British troops the next day. The occupation had two stages: the de facto stage from November 13 1918 to March 20 1920, and the de jure stage from de facto to the days following the Treaty of Lausanne. The occupation of Istanbul along with the occupation of İzmir, mobilized the establishment of the Turkish national movement and the Turkish War of Independence[24].

Peace Treaty

On 18 January 1919, the negotiations for a peace began with the Paris Peace Conference, 1919. The negotiations for a peace treaty continued at the Conference of London, and took definite shape only after the premiers' meeting at the San Remo conference in April 1920. France, Italy, and Great Britain, however, had secretly begun the partitioning of the Ottoman Empire as early as 1915. The Ottoman Government representatives signed the Treaty of Sèvres on August 10, 1920, however, treaty was not sent to Ottoman Parliament for ratification, as Parliament was abolished on March 18 1920 by the British, during the occupation of Istanbul. The treaty was never ratified by the Ottoman Empire[25][26] The Treaty of Sèvres was annulled in the course of the Turkish War of Independence and the parties signed and ratified the superseding Treaty of Lausanne in 1923.

Casualties

Timeline

|

Footnotes

- ^ Austro-Hungarian Army in the Ottoman Empire 1914-1918

- ^ Jung Peter, Austro-Hungarian Forces in World War 1 (Part 1),(Osprey, 2003), p.47

- ^ a b c d Ordered to Die: A History of the Ottoman Army in the First World War By Huseyin (FRW) Kivrikoglu, Edward J. Erickson Page 211

- ^ The Treaty of Alliance Between Germany and Turkey 2 August, 1914

- ^ a b Hinterhoff, Marshall Cavendish Illustrated Encyclopedia, pp.499-503

- ^ a b c The Encyclopedia Americana, 1920, v.28, p.403

- ^ Template:Harvard reference

- ^ R. G. Hovannisian. Armenia on the Road to Independence, 1918, University of California Press, Berkeley and Los Angeles, 1967, pg. 59

- ^ The Washington Post, November 12, 1914. "Armenian Join Russians" the extended information is a the image detail)

- ^ By Joan George "Merchants in Exile: The Armenians of Manchester, England, 1835-1935" page 184

- ^ Stanley Elphinstone Kerr. The Lions of Marash: personal experiences with American Near East Relief, 1919-1922 p. 30

- ^ The Hugh Chisholm, 1920, Encyclopedia Britannica, Encyclopedia Britannica, Company ltd., twelve edition p.198.

- ^ a b Avetoon Pesak Hacobian, 1917, Armenia and the War, p.77

- ^ Template:Harvard reference

- ^ Italian atrocities in world war two | Education | The Guardian:# Rory Carroll # The Guardian, # Monday June 25 2001

- ^ Richard G. Hovannisian, The Armenian People from Ancient to Modern Times, 244

- ^ a b (Erickson 2001, pp. 97)

- ^ a b A. F. Pollard, "A Short History Of The Great War" chapter VI: The first winter of the war.

- ^ (Erickson 2001, pp. 54)

- ^ a b (Pasdermadjian 1918, pp. 22)

- ^ Fromkin, 135.

- ^ a b Richard Hovannisian "The Armenian people from ancient to modern times" Pages 292-293

- ^ Mark Malkasian, Gha-Ra-Bagh": the emergence of the national democratic movement in Armenia page 22

- ^ Mustafa Kemal Pasha's speech on his arrival in Ankara in November 1919

- ^ Sunga, Lyal S. (1992-01-01). Individual Responsibility in International Law for Serious Human Rights Violations. Martinus Nijhoff Publishers. ISBN 0-7923-1453-0.

{{cite book}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Bernhardsson, Magnus (2005-12-20). Reclaiming a Plundered Past: archaeology and nation building in modern Iraq. University of Texas Press. ISBN 0-292-70947-1.

{{cite book}}: Check date values in:|date=(help)

Bibliography

- Erickson, Edward J. (2001). Ordered to Die: A History of the Ottoman Army in the First World War. Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 9780313315169.

- Pasdermadjian, Garegin (1918). Why Armenia Should be Free: Armenia's Role in the Present War. Hairenik Pub. Co. p. 45.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help)CS1 maint: ref duplicates default (link)

Further reading

- David R. Woodward: Hell in the Holy Land: World War I in the Middle East. Lexington 2006, ISBN 978-0-8131-2383-7

- W.E.D. Allen and Paul Muratoff, Caucasian Battlefields, A History of Wars on the Turco-Caucasian Border, 1828-1921, Nashville, TN, 1999 (reprint). ISBN 0898392969</ref>

- The Anglo-Russian Entente:Agreement concerning Persia 1907

- The French, British and Russian joint declaration over the situation in Armenia published on May 24, 1915

- Sykes-Picot Agreement 15 & 16 May, 1916.

- The Middle East during World War I By Professor David R Woodward for the BBC

- [1] War in Africa and the middle east.