Magna Carta

| Magna Carta | |

|---|---|

Magna Carta | |

| Created | 1215 |

| Location | Various copies |

| Part of the Politics series |

| Monarchy |

|---|

|

|

|

Magna Carta (also called Magna Carta Libertatum, the Great Charter of Liberty) is an English legal charter, originally issued in the year 1215. It was written in Latin and is therefore known by its Latin name. The usual English translation of Magna Carta is Great Charter.

Magna Carta required King John of England to proclaim certain rights (pertaining to freemen), respect certain legal procedures, and accept that his will could be bound by the law. It explicitly protected certain rights of the King's subjects, whether free or fettered — and implicitly supported what became the writ of habeas corpus, allowing appeal against unlawful imprisonment.

Magna Carta was arguably [according to whom?]the most significant [citation needed] early influence on the extensive historical process that led to the rule of constitutional law today in the English speaking world. However, it was "far from unique, either in content or form" [1]. A key statute of the uncodified British Constitution,[2] Magna Carta influenced the development of the common law [citation needed] and many constitutional documents, including the United States Constitution.[3] Many clauses were renewed throughout the Middle Ages, and continued to be renewed as late as the 18th century. By the second half of the 19th century, however, most clauses in their original form had been repealed from English law.

Magna Carta was the first document forced onto an English King by a group of his subjects (the barons) in an attempt to limit his powers by law and protect their privileges. It was preceded by the 1100 Charter of Liberties in which King Henry I voluntarily stated that his own powers were under the law.

In practice, Magna Carta in the medieval period mostly did not limit the power of Kings; but by the time of the English Civil War it had become an important symbol for those who wished to show that the King was bound by the law.

Magna Carta is normally understood [by whom?] to refer to a single document, that of 1215. Various amended versions of Magna Carta appeared in subsequent years however, and it is the 1297 version which remains on the statute books of England and Wales.

Magna Carta's "fame is primarily due, however, not to its intrinsic merits but the use parliamentarians made of it in their struggle with the Stuarts in the Seventeenth Century and the export of this myth to New England by the early settlers"[4].

Frequently this important document is compared to the Golden Bull of 1222 wich was created by the King Andrew II of Hungary. Similar ccircunstances forced the Hungarian King to elaborate this letter were he conffered privileges to the nobility and restricted the ones from the monarch. So both documents, The Magna Carta and the Golden Bull of 1222 are considered to be the most ancient bases for the modern and contemporary polithical systems.[5]

Background

After the Norman conquest of England in 1066 and advances in the 12th century, the English King had by 1199 become a powerful and influential monarch in Europe. Factors contributing to this include the sophisticated centralised government created by the procedures of the new Norman systems of governance and extensive Anglo-Norman land holdings within Normandy.

But after King John of England was crowned in 1199, a series of failures at home and abroad, combined with perceived abuses of the king's power, led the English barons to revolt and attempt to restrain what the king could legally do.

France

King John's actions in France were a major cause of discontent in the realm [citation needed]. At the time of his accession to the throne after Richard's death, there were no set rules to define the line of succession. King John, as Richard's younger brother, was crowned over Richard's nephew, Arthur of Brittany, since Arthur still had a claim over the Anjou empire. However, John needed the approval of the French king, Philip Augustus. To get it, John gave to Philip large tracts of the French-speaking Anjou territories.

When John later married Isabella of Angoulême, her previous fiancé (Hugh X of Lusignan, one of John's vassals) appealed to Philip, who then declared forfeit all of John's French lands, including the rich Normandy. Philip declared Arthur as the true ruler of the Anjou throne and invaded John's French holdings in mid-1202 to give it to him. John had to act to save face, but his eventual actions did not achieve this—Arthur disappeared in suspicious circumstances, and John was widely believed to have murdered him, thus losing the little support he had from his French barons.

After the defeat of John's allies at the Battle of Bouvines,[6] Philip retained all of John's northern French territories, including Normandy (although Aquitaine remained in English hands for a time). These serious military defeats, which lost to the English a major source of income, made John unpopular at home [citation needed]. Worse, to recoup his expenses, he had to further tax the already unhappy barons.

The Church

At the time of John's reign there was still a great deal of controversy as to how the Archbishop of Canterbury was to be elected, although it had become traditional that the monarch would appoint a candidate with the approval of the monks of Canterbury.

But in the early 13th century, the bishops began to want a say. To retain control, the monks elected one of their numbers to the role. But John, incensed at his lack of involvement in the proceedings, sent John de Gray, the Bishop of Norwich, to Rome as his choice. Pope Innocent III declared both choices invalid and persuaded the monks to elect Stephen Langton. Nevertheless, John refused to accept this choice and exiled the monks from the realm. Infuriated, Innocent ordered an interdict (prevention of public worship — mass, marriages, the ringing of church bells, etc.) in England in 1208, excommunicated John in 1209, and encouraged Philip to invade England in 1212.

John finally relented, and agreed to endorse Langton and allow the exiles to return. To placate the Pope, he gave England and Ireland as papal territories and rented them back as a fiefdom for 1,000 marks per annum. This surrender of autonomy to a foreign power further enraged the barons.

Taxes

King John I needed money for armies, but the loss of the French territories, especially Normandy, greatly reduced the state income, and a huge tax would need to be raised to reclaim these territories. Yet, it was difficult to raise taxes because of the tradition of keeping them unchanged.

John relied on clever manipulation of pre-existing rights, including those of forest law, which regulated the king's hunting preserves, which were easily violated and severely punished. John also increased the pre-existing scutage (feudal payment to an overlord replacing direct military service) eleven times in his seventeen years as king, as compared to eleven times during the reign of the preceding three monarchs. The last two of these increases were double the increase of their predecessors. He also imposed the first income tax, raising the (then) extortionate sum of £70,000.

Rebellion and signing of the document

By 1215, some of the most important barons in England had had enough, and with the support of Prince Louis the French Dauphin and King Alexander II of the Scots, they entered London in force on 10 June 1215,[7] with the city showing its sympathy with their cause by opening its gates to them. They, and many of the moderates not in overt rebellion, forced King John to agree to the "Articles of the Barons", to which his Great Seal was attached in the meadow at Runnymede on 15 June 1215. In return, the barons renewed their oaths of fealty to King John on 19 June 1215. The contemporary chronicler, Roger of Wendover, recorded the events in his Flores Historiarum.[8] A formal document to record the agreement was created by the royal chancery on 15 July: this was the original Magna Carta. An unknown number of copies of it were sent out to officials, such as royal sheriffs and bishops.

The most significant clause for King John at the time was clause 61, known as the "security clause", the longest portion of the document. This established a committee of 25 barons who could at any time meet and overrule the will of the King, through force by seizing his castles and possessions if needed.[9] This was based on a medieval legal practice known as distraint, but it was the first time it had been applied to a monarch. In addition, the King was to take an oath of loyalty to the committee.

Clause 61 essentially neutered John's power as a monarch, making him King in name only. He renounced it as soon as the barons left London, plunging England into a civil war, called the First Barons' War. Pope Innocent III also annulled the "shameful and demeaning agreement, forced upon the King by violence and fear." He rejected any call for restraints on the King, saying it impaired John's dignity. He saw it as an affront to the Church's authority over the King and the 'papal territories' of England and Ireland, and he released John from his oath to obey it.

Magna Carta re-issued

Prince Louis invaded England in 1216, and was proclaimed king in London in May of that year with the support of the barons. However, John died from dysentery on 18 October 1216, and this quickly changed the nature of the war. His nine-year-old son Henry was next in line for the throne. The royalists believed the rebel barons would find the idea of loyalty to the child Henry more palatable, so the boy was swiftly crowned Henry III in late October 1216, Louis's support for the English throne collapsed (he would go on to reign in France as Louis VIII), and the war ended.

Henry's regent, William Marshal reissued Magna Carta in his name on 12 November 1216 as a Royal concession, omitting some clauses, such as clause 61, and likewise again in 1217. When he turned 18 in 1225, Henry III reissued Magna Carta, this time in a shorter version with only 37 articles, as a concession of liberties in return for a fifteenth part of moveable goods[4].

Henry III ruled for 56 years (the longest reign of an English Monarch in the Medieval period) so that by the time of his death in 1272, Magna Carta had become a settled part of English legal precedent.

The Parliament of Henry III's son and heir, Edward I, reissued Magna Carta for the final time on 12 October 1297, as part of a statute called Confirmatio cartarum, reconfirming Henry III's shorter version of Magna Carta from 1225.

Content

Magna Carta was originally written in Latin. A large part of Magna Carta was copied, nearly word for word, from the Charter of Liberties of Henry I, issued when Henry I ascended to the throne in 1100, which bound the king [citation needed] to certain laws regarding the treatment of church officials and nobles, effectively granting certain civil liberties to the church and the English nobility.

The document commonly known as Magna Carta today is not the 1215 charter but a later charter of 1225, and is usually shown in the form of The Charter of 1297 when it was confirmed by Edward I. At the time of the 1215 charter, many of the provisions were not meant to make long term changes but simply to right the immediate wrongs, and therefore The Charter was reissued three times in the reign of Henry III (1216, 1217 and 1225) in order to provide for an updated version. After this, each individual king for the next two hundred years (until Henry V in 1416) personally confirmed the 1225 charter in his own charter.

Rights still in force today

For modern times, the most enduring legacy of Magna Carta is considered the right of habeas corpus [citation needed]. This right arises from what are now known as clauses 36, 38, 39, and 40 of the 1215 Magna Carta. The rights which are protected by habeus corpus had existed before Magna Carta, and writs with the same effect had been issued as early as the 12th Century, but Magna Carta was the first time that royal recognition of these rights had been written down.[10]

As the most recent version, it is the 1297 Charter which remains in legal force in England and Wales. Using the clauses in the 1297 charter (the content and numbering are somewhat different from the 1215 Charter): Clause 1 guarantees the freedom of the English Church. Although this originally meant freedom from the King [citation needed], later in history it was used for different purposes (see below). Clause 9 guarantees the "ancient liberties" of the City of London. Clause 29 guarantees a right to due process.

- I. FIRST, We have granted to God, and by this our present Charter have confirmed, for Us and our Heirs for ever, that the Church of England shall be free, and shall have all her whole Rights and Liberties inviolable. We have granted also, and given to all the Freemen of our Realm, for Us and our Heirs for ever, these Liberties under-written, to have and to hold to them and their Heirs, of Us and our Heirs for ever.

- IX. THE City of London shall have all the old Liberties and Customs which it hath been used to have. Moreover We will and grant, that all other Cities, Boroughs, Towns, and the Barons of the Five Ports, as with all other Ports, shall have all their Liberties and free Customs.

- XXIX. NO Freeman shall be taken or imprisoned, or be disseised of his Freehold, or Liberties, or free Customs, or be outlawed, or exiled, or any other wise destroyed; nor will We not pass upon him, nor condemn him, but by lawful judgment of his Peers, or by the Law of the land. We will sell to no man, we will not deny or defer to any man either Justice or Right.[11]

The repeal of clause 26 in 1829, by the Offences against the Person Act 1828 (9 Geo. 4 c. 31 s. 1),[11] was the first time a clause of Magna Carta was repealed. With the document's perceived protected status broken, in 150 years nearly the whole charter was repealed, leaving just Clauses 1, 9, and 29 still in force after 1969. Most of it was repealed in England and Wales by the Statute Law Revision Act 1863, and in Ireland by the Statute Law (Ireland) Revision Act 1872.[11]

| Clause | Repealing Act[11] |

|---|---|

| II | Statute Law Revision Act 1863 and Statute Law (Ireland) Revision Act 1872 |

| III | Statute Law Revision Act 1863 and Statute Law (Ireland) Revision Act 1872 |

| IV | Statute Law Revision Act 1863 and Statute Law (Ireland) Revision Act 1872 |

| V | Statute Law Revision Act 1863 and Statute Law (Ireland) Revision Act 1872 |

| VI | Statute Law Revision Act 1863 and Statute Law (Ireland) Revision Act 1872 |

| VII | Administration of Estates Act 1925, Administration of Estates Act (Northern Ireland) 1955 and Statute Law (Repeals) Act 1969 |

| VIII | Statute Law (Repeals) Act 1969 |

| X | Statute Law Revision Act 1948 |

| XI | Civil Procedure Acts Repeal Act 1879 |

| XII | Civil Procedure Acts Repeal Act 1879 |

| XIII | Statute Law Revision Act 1863 and Statute Law (Ireland) Revision Act 1872 |

| XIV | Criminal Law Act 1967 and Criminal Law Act (Northern Ireland) 1967 |

| XV | Statute Law (Repeals) Act 1969 |

| XVI | Statute Law (Repeals) Act 1969 |

| XVII | Statute Law Revision Act 1892 |

| XVIII | Crown Proceedings Act 1947 |

| XIX | Statute Law Revision Act 1863 and Statute Law (Ireland) Revision Act 1872 |

| XX | Statute Law Revision Act 1863 and Statute Law (Ireland) Revision Act 1872 |

| XXI | Statute Law Revision Act 1863 and Statute Law (Ireland) Revision Act 1872 |

| XXII | Statute Law Revision Act 1948 |

| XXIII | Statute Law (Repeals) Act 1969 |

| XXIV | Statute Law Revision Act 1863 and Statute Law (Ireland) Revision Act 1872 |

| XXV | Statute Law Revision Act 1948 |

| XXVI | Offences against the Person Act 1828 and Offences against the Person (Ireland) Act 1829 |

| XXVII | Statute Law Revision Act 1863 and Statute Law (Ireland) Revision Act 1872 |

| XXVIII | Statute Law Revision Act 1863 and Statute Law (Ireland) Revision Act 1872 |

| XXX | Statute Law (Repeals) Act 1969 |

| XXXI | Statute Law Revision Act 1863 and Statute Law (Ireland) Revision Act 1872 |

| XXXII | Statute Law Revision Act 1887 |

| XXXIII | Statute Law Revision Act 1863 and Statute Law (Ireland) Revision Act 1872 |

| XXXIV | Statute Law Revision Act 1863 and Statute Law (Ireland) Revision Act 1872 |

| XXXV | Sheriffs Act 1887 |

| XXXVI | Statute Law Revision Act 1863 and Statute Law (Ireland) Revision Act 1872 |

| XXXVII | Statute Law Revision Act 1863 and Statute Law (Ireland) Revision Act 1872 |

Feudal rights still in place in 1225

Several clauses were present in the 1225 charter but are no longer in force and would have no real place in the post-feudal world. Clauses 2 to 7 refer to the feudal death duties, defining the amounts and what to do if an heir to a fiefdom is underage or is a widow. Clause 23 provides no town or person should be forced to build a bridge across a river. Clause 33 demands the removal of all fish weirs. Clause 43 gives special provision for tax on reverted estates and Clause 44 states that forest law should only apply to those in the king's forest.

Feudal rights not in the 1225 charter

Some provisions have no bearing in the world today, since they are feudal rights and were not even included in the 1225 charter. Clauses 9 to 12, 14 to 16, and 25 to 26 deal with debt and taxes and Clause 27 with intestacy.

The other clauses state that no one may seize land in debt except as a last resort; that underage heirs and widows should not pay interest on inherited loans; that county rents will stay at their ancient amounts; and that the crown may only seize the value owed in payment of a debt, that aid (taxes for warfare or other emergency) must be reasonable, and that scutage (literally "shield[-payment]", payment in lieu of actual military service used to finance warfare) may only be sought with the consent of the kingdom.

Clause 14 states that the common consent of the kingdom was to be sought from a council of the archbishops, bishops, earls and greater Barons. This later became the great council, which led to the first parliament.

Judicial rights

Clauses 17 to 22 allowed for a fixed law court, which became the chancellery, and defines the scope and frequency of county assizes. They also state that fines should be proportionate to the offence, that they should not be influenced by ecclesiastical property in clergy trials, and that their peers should try people. Many think that this gave rise to jury and magistrate trial, but its only manifestation in the modern world was the right of a lord to a criminal trial in the House of Lords at first instance (abolished in 1948).

Clause 24 states that crown officials (such as sheriffs) may not try a crime in place of a judge. Clause 34 forbids repossession without a writ precipe. Clauses 36 to 38 state that writs for loss of life or limb are to be free, that someone may use reasonable force to secure their own land, and that no one can be tried on their own testimony alone.

Clauses 36, 38, 39 and 40 collectively define the right of Habeas Corpus. Clause 36 requires courts to make inquiries as to the whereabouts of a prisoner, and to do so without charging any fee. Clause 38 requires more than the mere word of an official, before any person could be put on trial. Clause 39 gives the courts exclusive rights to punish anyone. Clause 40 disallows the selling or the delay of justice. Clauses 36 and 38 were removed from the 1225 version, but were reinstated in later versions. The right of Habeas Corpus as such was first invoked in court in the year 1305.

Clause 54 says that no man may be imprisoned on the testimony of a woman except on the death of her husband.

Anti-corruption and fair trade

Clauses 28 to 32 state that no royal officer may take any commodity such as grain, wood or transport without payment or consent or force a knight to pay for something the knight could do himself, and that the king must return any lands confiscated from a felon within a year and a day.

Clause 35 sets out a list of standard measures, and Clauses 41 and 42 guarantee the safety and right of entry and exit of foreign merchants.

Clause 45 says that the King should only appoint royal officers where they are suitable for the post. In the United States, the Supreme Court of California interpreted clause 45 in 1974 as establishing a requirement at common law that a defendant faced with the potential of incarceration is entitled to a trial overseen by a law-trained judge.[12]

Clause 46 provides for the guardianship of monasteries.

Temporary provisions

Some provisions were for immediate effect and were not in any later charter. Clauses 47 and 48 abolish most of Forest Law (these were later taken out of Magna Carta and formed into a separate charter, the Charter of the Forest).[13] Clauses 49, 52 to 53 and 55 to 59 provide for the return of hostages, land and fines taken in John's reign.

Article 50 states that no member of the d'Athée family may be a royal officer. Article 51 calls for all foreign knights and mercenaries to leave the realm.

Articles 60, 62 and 63 provide for the application and observation of the Charter and say that the Charter is binding on the King and his heirs forever, but this was soon deemed dependent on each succeeding king reaffirming the Charter under his own seal.

Great Council

The first long-term constitutional effect arose from Clauses 14 and 61, which permitted a council composed of the most powerful men in the country to exist for the benefit of the state rather than in allegiance to the monarch [citation needed]. Members of the council were also allowed to renounce their oath of allegiance to the King in pressing circumstances and to pledge allegiance to the council and not to the King in certain instances. The common council was responsible for taxation, and although it was not representative, its members were bound by decisions made in their absence. The common council, later called the Great Council, was England's proto-parliament[citation needed].

The Great Council only existed to give input on the opinion of the kingdom as a whole, and it only had power to control scutage until 1258 when Henry III got into debt fighting in Sicily for the pope. The barons agreed to a tax in exchange for reform, leading to the Provisions of Oxford. But Henry got a papal bull allowing him to set aside the provisions and in 1262 told royal officers to ignore the provisions and only to obey Magna Carta. The barons revolted and seized the Tower of London, the Cinque ports and Gloucester. Initially the King surrendered, but when Louis IX of France arbitrated in favour of Henry, Henry crushed the rebellion. Later he ceded somewhat, passing the Statute of Marlborough in 1267, which allowed writs for breaches of Magna Carta to be free of charge, enabling anyone to have standing to apply the Charter.

This secured the position of the Great Council forever, but its powers were still very limited. The council originally only met three times per year and so was subservient to the King's council, Curiae Regis, who, unlike the Great Council, followed the king wherever he went.

Still, in some senses the council was an early form of parliament [citation needed]. It had the power to meet outside the authority of the King and was not appointed by him [citation needed]. While executive government descends from the Curiae Regis, parliament descends from the Great Council [citation needed], which was later called the parliamentum. However, the Great Council was very different from modern parliament. There were no knights, let alone commons, and it was composed of the most powerful men, rather than elected citizens.

Magna Carta had little effect on subsequent development of parliament until the Tudor period. Knights and county representatives attended the Great Council (Simon de Montfort's Parliament), and the council became far more representative under the model parliament of Edward I which included two knights from each county, two burgesses from each borough and two citizens from each city. The Commons separated from the Lords in 1341. The right of the Commons to exclusively sanction taxes (based on a withdrawn provision of Magna Carta) was re-asserted in 1407, although it was not in force in this period. The power vested in the Great Council by, albeit withdrawn, Clause 14 of Magna Carta became vested in the House of Commons but Magna Carta was all but forgotten for about a century, until the Tudors.

Tudor dynasty (1485–1603)

Magna Carta was the first entry on the statute books, but after 1472, it was not mentioned for a period of nearly 100 years. There was much ignorance about the document. The few who did know about the document spoke of a good king being forced by an unstable pope and rebellious barons "to attaine the shadow of seeming liberties" and that it was a product of a wrongful rebellion against the one true authority, the king. The original Magna Carta was seen [by whom?] as an ancient document with shadowy origins and as having no bearing on the Tudor world. Shakespeare's King John makes no mention of the Charter at all but focuses on the murder of Arthur. The Charter in the statute books was correctly thought to have arisen from the reign of Henry III.

First uses of the charter as a bill of rights

This statute was used widely in the reign of Henry VIII (1509–47) but was seen as no more special than any other statute and could be amended and removed. But later in the reign, the Lord Treasurer stated in the Star Chamber that many had lost their lives in the baronial wars fighting for the liberties which were guaranteed by the Charter, and therefore it should not so easily be overlooked as a simple and regular statute.

The church often attempted to invoke the first clause of the Charter to protect itself from the attacks by Henry, but this claim was given no credence. Francis Bacon was the first to try to use Clause 39 to guarantee due process in a trial.

Although there was a re-awakening of the use of Magna Carta in common law, it was not seen (as it was later) as an entrenched set of liberties guaranteed for the people against the Crown and Government. Rather, it was a normal statute, which gave a certain level of liberties, most of which could not be relied on, least of all against the king. Therefore, the Charter had little effect on the governance of the early Tudor period. Although lay parliament evolved from the Charter [citation needed], by this stage the powers of parliament had managed to exceed those humble beginnings. The Charter had no real effect until the Elizabethan era (1558–1603)

Reinterpretation of the charter

In the Elizabethan age, England was becoming a powerful force in Europe. In academia, earnest but futile attempts were made to prove that Parliament had Roman origins. The events at Runnymede in 1215 were "re-discovered"[according to whom?], allowing a possibility to show the antiquity of Parliament, and Magna Carta became synonymous with the idea of an ancient house with origins in Roman government.

The Charter was interpreted [according to whom?] as an attempt to return to a pre-Norman state of things. The Tudors saw the Charter as proof that their state of governance had existed since time immemorial and the Normans had been a brief break from this liberty and democracy. This claim is disputed in certain circles [where?] but explains how Magna Carta came to be regarded as such an important document.

Magna Carta again occupied legal minds, and it again began to shape how that government was run. Soon the Charter was seen as an immutable entity [by whom?]. In the trial of Arthur Hall for questioning the antiquity of the House, one of his alleged crimes was an attack on Magna Carta [citation needed].

Edward Coke's opinions

One of the first respected jurists to write seriously about the great charter was Edward Coke, who had a great deal to say on the subject and was influential in the way Magna Carta was perceived throughout the Tudor and Stuart periods, although his opinions changed across time and his writing in the Stuart period was more influential. In the Elizabethan period, Coke wrote of Parliament evolving alongside the monarchy and not existing by any allowance on the part of the monarch. However he was still fiercely loyal to Elizabeth, and the monarchy still judged the Charter in the same light it always had: an evil document wrung out of their forefathers by brute force. He therefore prevented a re-affirmation of the charter from passing the House, and although he spoke highly of the charter, he did not speak out against imprisonments without due process. This came back to haunt him later when he moved for a reaffirmation of the charter.

Role in the lead-up to the Civil War

By the time of the Stuarts (1603), Magna Carta had attained an almost mythical status for its admirers and was seen as representing a 'golden age' of English liberties extant prior to the Norman invasion. Whether or not this 'golden age' ever truly existed is open to debate; regardless, proponents of its application to English law saw themselves as leading England back to a pre-Norman state of affairs. What is true, however is that this age existed in the hearts and minds of people of the time. Magna Carta was not important because of the liberties it bestowed, but simply as 'proof' of what had come before; many great minds influentially exalted the Charter; by the seventeenth century, Coke was talking of the Charter as an indispensable method of limiting the powers of the Crown, a popular principle in the Stuart period where the kings were proclaiming their divine right and were looking, in the minds of some of their subjects, towards becoming absolute monarchs.

It was not the content of the Charter which has made it so important in the history of England, but more how it has been perceived in the popular mind. This is something that certainly started in the Stuart period, as the Charter represented many things, which are not to be found in the Charter itself. Firstly it was used to claim liberties against the Government in general rather than just the Crown and the officers of the crown, secondly that it represented that the laws and liberties of England, specifically Parliament, dated back to a time immemorial and thirdly, that it was not only just but right to usurp a king who disobeyed the law.

For the last of these reasons Magna Carta began to represent a danger to the monarchy[citation needed]; Elizabeth ordered that John Coke stop a bill from going through Parliament which would have reaffirmed the validity of the Charter, and Charles I ordered the suppression of a book which Coke intended to write on Magna Carta. The powers of Parliament were growing, and on Coke's death, parliament ordered his house to be searched; the manuscripts were recovered, and the book was published in 1642 (at the end of Charles I's Personal Rule). Parliament began to see Magna Carta as its best way of claiming supremacy over the crown [citation needed] and began to state that they were the sworn defenders of the liberties — fundamental and immemorial — which were to be found in the Charter.

In the four centuries since the Charter had originally catered for their creation, Parliament's power had increased greatly from their original level where they existed only for the purpose that the king had to seek their permission in order to raise scutage. They had become the only body allowed to raise tax, a right which although descended from the 1215 Great Charter was not guaranteed by it, since it was removed from the 1225 edition. Parliament had become so powerful that the Charter was being used both by those wishing to limit Parliament's power (as a new organ of the Crown), and by those who wished Parliament to rival the king's power (as a set of principles Parliament was sworn to defend against the king). When it became obvious that some people wished to limit the power of Parliament by claiming it to be tantamount to the crown, Parliament claimed they had the sole right of interpretation of the Charter.

This was an important step; for the first time Parliament was claiming itself a body as above the law; whereas one of the fundamental principles in English law was that the law, Parliament, the monarch, and the church held all, albeit to different extents. Parliament was claiming exactly what Magna Carta wanted to prevent the king from claiming, a claim of not being subject to any higher form of power. This was not claimed until ten years after the death of Lord Coke, but he would not have agreed with this , because he claimed in the English Constitution the law was supreme and all bodies of government were subservient to the supreme law, which is to say the common law [citation needed], as embodied [citation needed]in the Great Charter. These early discussions of Parliamentary sovereignty seemed to only involve the Charter as the entrenched law, and the discussions were simply about whether Parliament had enough power to repeal the document.

Although it was important for Parliament to be able to claim themselves more powerful than the King in the forthcoming struggle, the Charter provided for this very provision. Clause 61 of the Charter enables people [citation needed] to swear allegiance to what became the Great Council and later Parliament and therefore to renounce allegiance to the king. Moreover, Clause 61 allowed for the seizing of the kingdom by the body which later became Parliament if Magna Carta was not respected by the king or Lord Chief Justice [citation needed]. So there was no need to show any novel level of power in order to overthrow the king; it had already been set out in Magna Carta nearly half a millennium before. Parliament was not ready to repeal the Charter yet however, and in fact, it was cited as the reason why ship money was illegal (the first time Parliament overruled the king).

Trial of Archbishop Laud

Further proof of the significance of Magna Carta is shown in the trial of Archbishop Laud in 1645. Laud was tried with attempting to subvert the laws of England including writing a condemnation of Magna Carta claiming that as the Charter came about due to rebellion it was not valid (a widely held opinion less than a century before, when the 'true' Magna Carta was thought to be the 1225 edition, with the 1215 edition being considered less valid for this very reason). However, Laud was not trying to say that Magna Carta was evil, and he actually used the document in his defence. He claimed his trial was against the right of the freedom of the church (as the Bishops were voted out of Parliament in order to allow for parliamentary condemnation of him) and, that he was not given the benefit of due process contrary to Clauses 1 and 39 of the Charter. By this stage, Magna Carta had passed a great distance beyond the original intentions for the document, and the Great Council had evolved beyond a body merely ensuring the application of the Charter. It had gotten to the stage where the Great Council or Parliament was inseparable from the ideas of the Crown as described in the Charter and therefore it was potentially not just the King that was bound by the Charter, but Parliament also.

Civil War and interregnum

After the seven years of the English Civil War (1642–49), after the king had surrendered and had been executed, it seemed Magna Carta no longer applied, as there was no King. Oliver Cromwell was accused of destroying Magna Carta, and many thought he should be crowned just so that it would apply.[citation needed] Cromwell had much disdain for Magna Carta, at one point describing it as "Magna Farta" to a defendant who sought to rely on it.[14]

In this time of foment, there were many revolutionary theorists, and many based their theories at least initially on Magna Carta, in the misguided belief that Magna Carta guaranteed liberty and equality for all.

Levellers

This section needs additional citations for verification. (September 2008) |

The Levellers believed that all should be equal and free without distinction of class or status. They believed that Magna Carta was the 'political bible', which should be prized above any other law and that it could not be repealed. They prized it so highly that they believed all (such as Archbishop Laud) who "trod Magna Carta ... under their feet" deserved to be attacked at all levels. The original idea was to achieve this through Parliament but there was little support, because at the time the Parliament was seeking to impose itself as above Magna Carta. The Levellers claimed Magna Carta was above any branch of government, and this led to the upper echelons of the Leveller movement denouncing Parliament. They claimed that Parliament's primary purpose was not to rule the people directly but to protect the people from the extremes of the King; they claimed that Magna Carta adequately did this and therefore Parliament should be subservient to it.

After the Civil War, Cromwell refused to support the Levellers and was denounced as a traitor to Magna Carta. The importance of Magna Carta was greatly magnified in the eyes of the Levellers. John Lilburne, one of the leaders of the movement, was known for his great advocacy of the Charter and was often known to explain its purpose to lay people and to expose the misspeaking against it in the popular press of the time. He was quoted as saying the ground and foundation of my freedome I build upon the grand charter of England. However, as it became apparent that Magna Carta did not grant the level of liberty demanded by the Levellers, the movement reduced its advocacy of it. William Walwyn, another leader of the movement, advocated natural law and other doctrines as the primary principles of the movement. This was mainly because the obvious intention of Magna Carta was to grant rights only to the barons and the episcopacy, and not the general and egalitarian rights the Levellers were claiming. Also influential, however, was Spelman's rediscovery of the existence of the feudal system at the time of Magna Carta, which seemed to have less and less effect on the world of the time. The only right, which the Levellers could trace back to 1215, possibly prized over all others, was the right to due process granted by Clause 39. One thing the Levellers did agree on with the popular beliefs of the time was that Magna Carta was an attempt to return to the fabled pre-Norman 'golden age'.

Diggers

However, not all such groups advocated Magna Carta. The Diggers were a very early socialistic group who called for all land to be available to all for farming and the like. Gerrard Winstanley, a leader of the group, despised Magna Carta as a show of the hypocrisy of the post-Norman law, since Parliament and the courts advocated Magna Carta and yet did not even follow it themselves. The Diggers did, however, believe in the pre-Norman golden age and wished to return to it, and they called for the abolition of all Norman and post-Norman law.

Charles II

The Commonwealth was relatively short lived however, and when Charles II took the throne in 1660, he vowed to respect both the common law and the Charter. Parliament was established as the everyday government of Britain [citation needed], independent of the King but not more powerful.[citation needed] However, the struggles based on the Charter were far from over and took on the form of the struggle for supremacy between the two Houses of Parliament [citation needed].

Within Parliament

In 1664, the British navy seized Dutch lands in both Africa and America leading to full-scale war with the Netherlands in 1665. The Lord Chancellor Edward Lord Clarendon, resisted an alliance with the Spanish and Swedes in favour of maintaining a relationship with the French, who were the allies of the Dutch. This lack of a coherent policy led to the Second Anglo-Dutch War (1665–67), with the Dutch burning ships in the docks at Chatham, and the blame was placed on Clarendon. The Commons demanded that Clarendon be indicted before the Lords, but the Lords refused, citing the due process requirements of the Charter, giving Clarendon the time to escape to Europe.

A very similar set of events followed in 1678 when the Commons asked the Lords to indict Thomas Lord Danby on a charge of fraternising with the French. As with Clarendon the Lords refused, again citing Magna Carta and their own supremacy as the upper house. Before the quarrel could be resolved, Charles dissolved the Parliament. When Parliament was re-seated in 1681, again the Commons attempted to force an indictment in the Lords. This time Edward Fitzharris who was accused of writing libellously that the King was involved in a papist plot with the French (including the overthrowing of Magna Carta). However, the Lords doubted the veracity of the claim and refused to try Fitzharris saying Magna Carta stated that everyone must be subject to due process and therefore he must be tried in a lower court first. This time the Commons retorted that it was the Lords who were denying justice under Clause 39 and that the Commons were right to cite the Charter as their precedent. Again, before any true conclusions could be drawn Charles dissolved the Parliament, although more to serve his own ends and to rid himself of a predominantly Whig Parliament, and Fitzharris was tried in a regular court (the King's Bench) and executed for treason. Here the Charter, once again, was used far beyond the content of its provisions, and simply being used as a representation of justice. Each house was claiming the Charter under Clause 39 supported its supremacy, but the power of the King was still too great for either house to come out fully as the more powerful.

Outside Parliament

The squabble also continued outside the Palace of Westminster. In 1667 the Lord Chief Justice and important member of the House of Lords, Lord Keeling, forced a grand jury of Somersetshire to return a verdict of murder when they wanted to return one of manslaughter.[15] However, his biggest crime in the eyes of the Commons was that, when the jury objected on the grounds of Magna Carta, he scoffed and exclaimed "Magna Farta, [sic] what ado with this have we?"[16] The Commons were incensed at this abuse of the Charter and accused him of endangering the liberties of the people.[15] However, the Lords claimed he was just referring to the inappropriateness of the Charter in this context, but Keeling apologised anyway. In 1681 the next Lord Chief Justice, Lord Scroggs, was condemned by the Commons first for being too severe in the so-called 'papist plot trials' and second for dismissing another Middlesex grand jury in order to secure against the indictment of the Duke of York, the Catholic younger brother of the King later to become James II. Charles again dissolved Parliament before the Commons could impeach Scroggs, and removed him from office on a good pension. Just as it seemed that the Commons might be able to impose their supremacy over the Lords, the King intervened and proved he was still the most powerful force in the government. However, it was certainly beginning to become established that the Commons were the primary branch of Government, and they used the Charter as much as they could in order to achieve this end.

Supremacy of the Commons

This was not the end of the struggle however, and in 1679 the Commons passed the Habeas Corpus Act of 1679, which greatly reduced the powers of the Crown. The act passed through the Lords by a small majority, arguably [by whom?] establishing the Commons as the more powerful House. This was the first time since the importance of the Charter had been so magnified that the Government had admitted that the liberties granted by the Charter were inadequate. However, this did not completely oust the position of the Charter as a symbol of the law of the 'golden age' and the basis of common law.

It did not take long before the questioning of the Charter really took off and Sir Matthew Hale soon afterwards introduced a new doctrine of common law based on the principle that the Crown (including the government cabinet in that definition) made all law and could only be bound by the law of God, and showed that the 1215 charter was effectively overruled by the 1225 charter, further undermining the idea that the charter was unassailable, adding credence to the idea that the Commons were a supreme branch of Government. Some [who?] completely denied the relevance of the 1215 Charter as it was forced upon the King by rebellion (although the fact that the 1225 charter was forced on a boy by his guardians was overlooked). It was similarly argued [by whom?] against the Charter that it was nothing more than a relaxation of the rigid feudal laws and therefore had no meaning outside of that application.

Glorious Revolution

The danger posed by the fact that Charles II had no legitimate child was becoming more and more real, as this meant that the heir apparent was the Duke of York, a Catholic and firm believer in the divine right of kings, threatening the establishment of the Commons as the most powerful arm of government [citation needed]. Parliament did all it could to prevent James's succession but was prevented when Charles dissolved the Parliament. In February 1685, Charles died of a stroke and James II assumed the thrones of England, Ireland and Scotland. Almost straight-away James attempted to impose Catholicism as the religion of the country [citation needed] and to regain the royal prerogative now vested in the Parliament. Parliament was slightly placated when James's four-year-old son died in 1677 and it seemed his Protestant daughter Mary would take his throne. However when James's second wife, Mary of Modena, gave birth to a male heir in 1688 Parliament could not take the risk that another Catholic monarch would assume the throne and take away their power.

Forces of the Dutch Republic commanded by Stadtholder William III of Orange invaded the country in November 1688 to pre-empt the threat of an Anglo-French Catholic alliance. A special Convention Parliament was called and declared that James had broken the contract of Magna Carta by fleeing the capital and throwing the Great Seal of the Realm in the River Thames, thereby nullifying his claim to the throne.

This proved [according to whom?] that Parliament had become the major power in the British Government. William III of Orange and Mary, James II's eldest daughter were made joint sovereigns in February 1689. The Declaration of Rights, 23 Heads of Grievances formulated by a special commission, was read aloud before William and Mary accepted the throne. They were crowned on April 11, swearing an oath to uphold the laws made by Parliament.

The Bill of Rights was passed by Parliament in December 1689 and was a re-statement in statutory form of the Declaration of Rights. It went far beyond what Magna Carta had ever set out to achieve. It stated that the Crown could not make law without Parliament. Although the raising of taxes was specifically mentioned, it did not limit itself to such, as Magna Carta did. However, one important thing to note is that the writers of the Bill did not seem to think that the Bill included any new provisions of law; all the powers it 'removes' from the crown it refers to as 'pretended' powers, insinuating that the rights of Parliament listed in the Bill already existed under a different authority, presumably Magna Carta. So the importance of Magna Carta was not completely extinguished at this point, although it was somewhat diminished.

Eighteenth century

The power of the Magna Carta myth still existed in the 18th century; in 1700 Samuel Johnson talked of Magna Carta being "born with a grey beard" referring to the belief that the liberties set out in the Charter harked back to the Golden Age and time immemorial. However, ideas about the nature of law in general were beginning to change. In 1716 the Septennial Act was passed, which had a number of consequences. Firstly, it showed that Parliament no longer considered its previous statutes unassailable, as this act provided that the parliamentary term was to be seven years, whereas fewer than twenty-five years had passed since the Triennial Act (1694), which provided that a parliamentary term was to be three years. It also greatly extended the powers of Parliament. Previously, all legislation that passed in a parliamentary session had to be listed in the election manifesto, so in effect the electorate was consulted on all issues that were to be brought before Parliament. However, with a seven-year term, it was unlikely, if not impossible, that all the legislation passed would be discussed at the election. This gave Parliament the freedom to legislate as it liked during its term. This was not Parliamentary sovereignty as understood today however, as although Parliament could overrule its own statutes, it was still considered itself bound by the higher law, such as Magna Carta. Arguments for Parliamentary sovereignty were not new; however, even its proponents would not have expected Parliament to be as powerful as it is today. For example, in the previous century, Coke had discussed how Parliament might well have the power to repeal the common law and Magna Carta, but they were, in practice, prohibited from doing so, as the common law and Magna Carta were so important in the constitution that it would be dangerous to the continuing existence of the constitution to ever repeal them.

Extent of the Commons' powers

In 1722 the Bishop of Rochester (Francis Atterbury (a Stuart Jacobite)), a member of the House of Lords, was accused of treason. The Commons locked him in the Tower of London, and introduced a bill intending to remove him from his post and send him into exile. This, once again, brought up the subject of which was the more powerful house, and exactly how far that power went. Atterbury claimed, and many agreed, that the Commons had no dominion over the Lords. Other influential people disagreed however; for example, the Bishop of Salisbury (also a Lord) was of the strong opinion that the powers of Parliament, mainly vested in the Commons, were sovereign and unlimited and therefore there could be no limit on those powers at all, implying the dominion of the lower house over the upper house. Many intellectuals agreed; Jonathan Swift went so far as to say that Parliament's powers extended to altering or repealing Magna Carta. This claim was still controversial, and the argument incensed the Tories. Bolingbroke spoke of the day when "liberty is restored and the radiant volume of Magna Carta is returned to its former position of Glory". This belief was anchored in the relatively new theory that when William the Conqueror invaded England he only conquered the throne, not the land, and he therefore assumed the same position in law as the Saxon rulers before him. The Charter was therefore a recapitulation or codification of these laws rather than (as previously believed) an attempt to reinstate these laws after the tyrannical Norman Kings. This implied that these rights had existed constantly from the 'golden age immemorial' and could never be removed by any government. The Whigs on the other hand claimed that the Charter only benefited the nobility and the church and granted nowhere near the liberty they had come to expect. However although the Whigs attacked the content of the Charter, they did not actually attack the myth of the 'golden age' or attempt to say that the Charter could be repealed, and the myth remained as immutable as ever.

America

The Stamp Act 1765 extended the stamp duty, which had been in force on home territory since 1694 to cover the American colonies as well. However, colonists of the Thirteen Colonies despised this since they were not represented in Parliament and refused to accept that an external body, which did not represent them, could tax them in what they saw was a denial of their rights as Englishmen. The cry "no taxation without representation" rang throughout the colonies.

The influence of Magna Carta can be clearly seen in the United States Bill of Rights, which enumerates various rights of the people and restrictions on government power, such as:

No person shall be ... deprived of life, liberty, or property, without due process of law.

Article 21 from the Declaration of Rights in the Maryland Constitution of 1776 reads:

That no freeman ought to be taken, or imprisoned, or disseized of his freehold, liberties, or privileges, or outlawed, or exiled, or in any manner destroyed, or deprived of his life, liberty, or property, but by the judgment of his peers, or by the law of the land.

The Ninth Amendment to the United States Constitution states that, "The enumeration in the Constitution, of certain rights, shall not be construed to deny or disparage others retained by the people." The framers of the United States Constitution wished to ensure that rights they already held, such as those provided by the Magna Carta, were not lost unless explicitly curtailed in the new United States Constitution.[17][18]

Parliamentary Sovereignty

The doctrine of parliamentary supremacy if not parliamentary sovereignty had all but emerged by the regency; William Blackstone argued strongly for sovereignty in his Commentaries on the English Law in 1765. He essentially argued that absolute supremacy must exist in one of the arms of Government and he certainly thought it resided in Parliament as Parliament could legislate on anything and potentially could even legislate the impossible as valid law if not practical policy. The debate over whether of not Parliament could limit or overrule the supposed rights granted by Magna Carta was to prove to be the basis for the discussion over parliamentary sovereignty; however Blackstone preached that Parliament should respect Magna Carta as a show of law from time immemorial, and the other great legal mind of the time, Jeremy Bentham used The Charter to attack the legal abuses of his time.

In 1763 an MP, John Wilkes was arrested for writing an inflammatory pamphlet, No. 45, 23 April 1763; however he cited Magna Carta incessantly, and the weight that Magna Carta held at the time meant Parliament was reluctant to continue the charge, and he was released and awarded damages for the wrongful seizing of his papers as the general warrant under which he was arrested was deemed illegal. However, he was still expelled from Parliament after spending a week in the Tower of London. He was abroad for a number of years until 1768 when he returned and failed to be elected as the MP for London; unperturbed, however, he stood again for Middlesex but he was expelled again, on the basis of the earlier offence, the following year. He stood again, however, and was elected yet again, but the Commons ruled that he was ineligible to sit. At the next three re-elections Wilkes again was the champion, but the house did not relent and his opponent, Lutteral, was declared the winner. The treatment of Wilkes caused a furore in Parliament, with Lord Camden denouncing the action as a contravention of Magna Carta. Wilkes made the issue a national one and the issue was taken up by the populace, and there were very popular prints of him being arrested while teaching his son about Magna Carta all over the country. He had the support of the Corporation of London, long seeking to establish its supremacy over Parliament based on The Charter itself. The fight for the charter was misplaced and it was merely the idea of the liberties which were supposedly enshrined in The Charter that people were fighting for. It is no coincidence that those who supported Wilkes would have little or no knowledge of the actual content of The Charter, or, if they did, were looking to protect their own position based on The Charter. Wilkes re-entered the house in 1774. He had talked of Magna Carta as he knew it would capture public support to achieve his aims, but he had started the ball rolling for a reform movement to 'restore the constitution' through a more representative, less powerful, and shorter-termed Parliament.

One of the principal reformists was a man called Granville Sharp who was a philanthropist who had on his list of causes the Society for the Abolition of Slavery and The Society for the Conversion of the Jews. Sharp called for the reformation of Parliament based on Magna Carta, and devised a doctrine to back this up, the doctrine of accumulative authority. This theory stated that almost innumerable parliaments had approved of Magna Carta, and therefore it would take the same amount of Parliaments to repeal The Charter. As with many, he accepted the supremacy of Parliament as an institution, but he did not believe that this power was without restraint, namely that they could not repeal Magna Carta. Many reformists agreed that The Charter was a statement of the liberties of the mythical and immemorial golden age, but there was a popular movement to have a holiday to commemorate the signing of The Charter in a similar way to the American 4 July holiday; however, very few went as far as Sharp.

Although there was a popular movement to resist the sovereignty of Parliament based on The Charter, there were still a great number of people who thought that The Charter was over-rated. John Cartwright pointed out in 1774 that Magna Carta could not possibly have existed unless there was a firm constitution beforehand to facilitate its use. He went even further, later, and claimed that The Charter was not even part of the constitution but merely a codification of what the constitution was at the time. Cartwright suggested that there should be a new Magna Carta based on equality and rights for all, not just for landed persons.

The work of people like Cartwright was fast showing that the rights granted by The Charter were out of pace with the developments which followed in the next six centuries. However there were certain provisions, such as Clauses 23 and 39, which were not only still valid then but which still form the basis of important rights in the present English law. Undeniably, though, Magna Carta was diminishing in importance, and the arguments for having a fully sovereign Parliament were becoming more and more accepted. Many in the house still supported The Charter, however, such as Sir Francis Burdett who called for a return to the constitution of Magna Carta in 1809 and denounced the house for taking proceedings against the radical John Gale Jones, for denouncing the house as acting in contravention of Magna Carta. Burdett was largely ignored, as by this stage Magna Carta had largely lost its appeal, but he continued, claiming that the Long Parliament had usurped all the power then enjoyed by the Parliament of the time; he stated that Parliament was constantly acting against Magna Carta (although he was referring to their judicial rather than their legislative practice) which they did not have the right to do; he achieved popular support and there were riots across London when he was arrested for these claims, and again a popular print circulated of him being arrested whilst teaching his son about Magna Carta

With the popular movements being in favour of the liberties of The Charter, and Parliament trying to establish their own sovereignty there needed to be some sort of action in order to swing the balance in favour of one or the other. However, all that occurred was the Reform Act 1832 which was such a compromise that it ended up pleasing no one. Due to their disappointment in the Reform Act a group was founded calling itself the Chartists; they called for a return to the constitution of Magna Carta and eventually culminated in a codification of what they saw as the existing rights of the People; the People's Charter. At a rally for the Chartists in 1838 the Reverend Raynor demanded a return to the constitution of The Charter; freedom of speech, of worship, and of congress. This is a perfect example of how the idea of The Charter went so far beyond the actual content of The Charter: it depicted for many people the idea of total liberty whereas the actual liberties granted by The Charter were very limited and by no means intended to be applied to all. It was this over-exaggeration of The Charter that eventually led to its downfall. The more people expected to get from The Charter, the less Parliament was willing to attempt to cater to this expectation, and eventually writers such as Tom Paine rebutted the claims of those such as the Chartists. This meant that the educated were no longer supporting any of these claims, and therefore the Myth gradually faded into obscurity, and the final claim against sovereignty of Parliament was erased, and the road was open to the establishment of this doctrine.

Chartists

The major breakthrough occurred in 1828 with the passing of the Offences against the Person Act 1828, which for the first time repealed a clause of Magna Carta: clause 36. With the myth broken, within 150 years nearly the whole charter was repealed.

The Reform Act 1832 fixed some of the most glaring problems in the political system, but did not go nearly far enough for a group that called itself the Chartists, who called for a return to the constitution of Magna Carta,[citation needed] and eventually created a codification of what they saw as the existing rights of the People, the People's Charter. At a rally for the Chartists in 1838 the Reverend Raynor demanded a return to the constitution of the Charter; freedom of speech, worship and congress. This is a perfect example of how the idea of the Charter went so far beyond its actual content: it depicted for many people the idea of total liberty. It was this exaggeration of the Charter that eventually led to its downfall. The more people expected to get from the Charter, the less Parliament was willing to attempt to cater to this expectation, and eventually writers such as Tom Paine refuted the claims about the Charter made by those such as the Chartists. This meant that the educated no longer supported these claims, and the power of Magna Carta as a symbol of freedom gradually faded into obscurity.

Influences on later constitutions

Many later attempts to draft constitutional forms of government, including the United States Constitution, trace their lineage back to this source document. The United States Supreme Court has explicitly referenced Lord Coke's analysis of Magna Carta as an antecedent of the Sixth Amendment's right to a speedy trial.[19]

Magna Carta has influenced international law as well: Eleanor Roosevelt referred to the Universal Declaration of Human Rights as "a Magna Carta for all mankind". Magna Carta is thought to be the crucial turning point in the struggle to establish freedom and a key element in the transformation of constitutional thinking throughout the world. When Englishmen left their homeland to establish colonies in the new world, they brought with them charters that guaranteed they and their heirs would "have and enjoy all liberties and immunities of free and natural subjects." (quoted from wall of The National Archives). In 1606, Sir Edward Coke, who drafted the Virginia Charter, had highly praised Magna Carta, which reflected many of its values and themes into the Virginia Charter (Howard 28). Colonists were also aware of their rights that came from Magna Carta. When American colonists raised arms against England, they were fighting not so much for new freedom, but to preserve liberties, many of which dated back to the 13th century Magna Carta. In 1787 when the representatives of America gathered to draft a constitution, they built upon the legal system they knew and admired: English common law that had evolved from Magna Carta (National Archives).

The ideas addressed in the great charter that are found today are particularly obvious. The American Constitution is the "supreme law of the land", recalling the manner in which Magna Carta had come to be regarded as fundamental law. This heritage is quite apparent. In comparing Magna Carta with the Bill of Rights: the Fifth Amendment guarantees: "No person shall be deprived of life, liberty or property without due process of law." In addition, the United States Constitution included a similar writ in the Suspension Clause, article 1, section 9: "The privilege of the writ habeas corpus shall not be suspended, unless when in cases of rebellion or invasion, the public safety may require it." Written 575 years earlier, Magna Carta states, "No free man shall be taken, imprisoned, disseised, outlawed, banished, or in any way destroyed, not will we proceed against or prosecute him, except by the lawful judgment of his peers and by the law of the land." (qtd. in Howard pg VI: Foreword). Each of these proclaim no man may be imprisoned or detained without proof that they did wrong.

Jews in England

Magna Carta contained two articles related to money lending and Jews in England. Jewish involvement with money lending caused Christian resentment, because the Church forbade usury; it was seen as vice and was punishable by excommunication, although Jews, as non-Christians, could not be excommunicated and were thus in a legal grey area. Secular leaders, unlike the Church, tolerated the practice of Jewish usury because it gave the leaders opportunity for personal enrichment. This resulted in a complicated legal situation: debtors were frequently trying to bring their Jewish creditors before Church courts, where debts would be absolved as illegal, while the Jews were trying to get their debtors tried in secular courts, where they would be able to collect plus interest. The relations between the debtors and creditors would often become very nasty. There were many attempts over centuries to resolve this problem, and Magna Carta contains one example of the legal code of the time on this issue:

- If one who has borrowed from the Jews any sum, great or small, die before that loan be repaid, the debt shall not bear interest while the heir is under age, of whomsoever he may hold; and if the debt fall into our hands, we will not take anything except the principal sum contained in the bond. And if anyone die indebted to the Jews, his wife shall have her dower and pay nothing of that debt; and if any children of the deceased are left under age, necessaries shall be provided for them in keeping with the holding of the deceased; and out of the residue the debt shall be paid, reserving, however, service due to feudal lords; in like manner let it be done touching debts due to others than Jews.[20]

After the Pope annulled Magna Carta, future versions contained no mention of Jews. The Church saw Jews as a threat to their authority, and the welfare of Christians, because of their special relationship to Kings as moneylenders. "Jews are the sponges of kings," wrote the theologian William de Montibus, "they are bloodsuckers of Christian purses, by whose robbery kings dispoil and deprive poor men of their goods." Thus the specific singling out of Jewish moneylenders seen in Magna Carta originated in part because of Christian nobles who permitted the otherwise illegal activity of usury, a symptom of the larger ongoing power struggle between Church and State during the Middle Ages.

Popular perceptions

Symbol and practice

Magna Carta is often a symbol for the first time the citizens of England were granted rights against an absolute king. However, in practice the Commons could not enforce Magna Carta in the few situations where it applied to them, so its reach was limited. Also, a large part of Magna Carta was copied, nearly word for word, from the Charter of Liberties of Henry I, issued when Henry I rose to the throne in 1100, which bound the king to laws which effectively granted certain civil liberties to the church and the English nobility.

Many documents form Magna Carta

The document commonly known as Magna Carta today is not the 1215 charter, but a later charter of 1225, and is usually shown in the form of the Charter of 1297 when it was confirmed by Edward I. At the time of the 1215 charter, many of the provisions were not meant to make long-term changes but simply to right some immediate wrongs; therefore, the Charter was reissued three times in the reign of Henry III (1216, 1217 and 1225). After this, each king for the next 200 years (until Henry V in 1416) personally confirmed the 1225 charter in his own charter. It is not thought of as one document but rather a variety of documents coming together to form one Magna Carta.

The document was unsigned

Popular perception is that King John and the barons signed Magna Carta. There were no signatures on the original document, however, only a single seal placed by the king. The words of the charter — Data per manum nostram — signify that the document was personally given by the king's hand. By placing his seal on the document, the King and the barons followed common law that a seal was sufficient to authenticate a deed, though it had to be done in front of witnesses. John's seal was the only one, and he did not sign it. The barons neither signed nor attached their seals to it.[21]

Perception in America

The document is also honoured in America, where it is an antecedent of the United States Constitution and Bill of Rights. In 1957, the American Bar Association erected the Runnymede Memorial.[22] In 1976, the UK lent an original 1215 Magna Carta to the U.S. for its bicentennial celebrations, and also donated an ornate case to display it, which included a gold replica of Magna Carta. The case and gold replica are still on display in the U.S. Capitol Rotunda in Washington, D.C.[23]

21st-century Britain

In 2006, BBC History held a poll to recommend a date for a proposed "Britain Day". 15 June, as the date of the signing of the original 1215 Magna Carta, received most votes, above other suggestions such as D-Day, VE Day, and Remembrance Day. The outcome was not binding, although the then Chancellor Gordon Brown had previously given his support to the idea of a new national day to celebrate British identity.[24] It was used as the name for an anti-surveillance movement in the 2008 BBC series The Last Enemy. According to a poll carried out by YouGov in 2008, 45% of the British public do not know what Magna Carta is.[25] However, its perceived guarantee of trial by jury and other civil liberties led to Tony Benn to refer to the debate over whether to increase the maximum time terrorist suspects could be held without charge from 28 to 42 days as "the day Magna Carta was repealed".[26]

Usage of the definite article, spelling "Magna Charta"

Since there is no direct, consistent correlate of the English definite article in Latin, the usual academic convention is to refer to the document in English without the article as "Magna Carta" rather than "the Magna Carta". According to the Oxford English Dictionary, the first written appearance of the term was in 1218: "Concesserimus libertates quasdam scriptas in magna carta nostra de libertatibus" (Latin: "We concede the certain liberties here written in our great charter of liberties"). However, "the Magna Carta" is frequently used in both academic and non-academic speech.

Especially in the past, the document has also been referred to as "Magna Charta", but the pronunciation was the same. "Magna Charta" is still an acceptable variant spelling recorded in many dictionaries due to continued use in some reputable sources. From the 13th to the 17th centuries, only the spelling "Magna Carta" was used. The spelling "Magna Charta" began to be used in the 18th century but never became more common despite also being used by some reputable writers.[27][28]

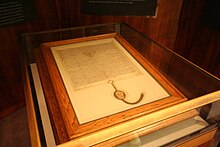

Copies

Numerous copies were made each time it was issued, so all of the participants would each have one — in the case of the 1215 copy, one for the royal archives, one for the Cinque Ports, and one for each of the 40 counties of the time. Several of those copies still exist and some are on permanent display. If there ever was one single 'master copy' of Magna Carta sealed by King John in 1215, it has not survived. Four contemporaneous copies (known as "exemplifications") remain, all of which are located in England:

- The 'burnt copy', which was found in the records of Dover Castle in the 17th century and so is assumed to be the copy that was sent to the Cinque Ports. It was subsequently involved at a house fire at its owner's property, making it all but illegible. It is the only one of the four to have its seal surviving, although this too was melted out of shape in the fire. It is currently held by the British Library.

- Another supposedly original, but possibly amended version of Magna Carta is on show just outside of the chamber of the House of Lords situated in the Palace of Westminster.

- One owned by Lincoln Cathedral, normally on display at Lincoln Castle. It has an unbroken attested history at Lincoln since 1216. We hear of it in 1800 when the Chapter Clerk of the Cathedral reported that he held it in the Common Chamber, and then nothing until 1846 when the Chapter Clerk of that time moved it from within the Cathedral to a property just outside. In 1848, Magna Carta was shown to a visiting group who reported it as "hanging on the wall in an oak frame in beautiful preservation". It went to the New York World Fair in 1939. In 1941, after war broke out with Japan, Magna Carta was sent to Fort Knox, along with the U.S. Declaration of Independence and Constitution, until 1944, when it was deemed safe to return them.[29] Having returned to Lincoln, it has been back to America on various occasions since then.[30] It was taken out of display for a time to undergo conservation in preparation for its visit to America, where it was exhibited at the Contemporary Art Center of Virginia from 30 March to 18 June 2007 in recognition of the Jamestown quadricentennial.[31][32] From 4 July to 25 July 2007, the document was displayed at the National Constitution Center in Philadelphia,[33] returning to Lincoln Castle afterwards. The document returned to New York to be displayed at the Fraunces Tavern Museum from 15 September to 15 December 2009.[34][35]

- One owned by and displayed at Salisbury Cathedral. It is the best preserved of the four.[36]

Other early versions of Magna Carta survive. Durham Cathedral possesses 1216, 1217, and 1225 copies.[37]

A near-perfect 1217 copy is held by Hereford Cathedral and is occasionally displayed alongside the Mappa Mundi in the cathedral's chained library. Remarkably, the Hereford Magna Carta is the only one known to survive along with an early version of a Magna Carta 'users manual', a small document that was sent along with Magna Carta telling the Sheriff of the county to observe the conditions outlined in the document.[38]

Four copies are held by the Bodleian Library in Oxford. Three of these are 1217 issues and one a 1225 issue. On 10 December 2007, these were put on public display for the first time.[39]

In 1952 the Australian Government purchased a 1297 copy of Magna Carta for £12,500 from King's School, Bruton, England.[40] This copy is now on display in the Members' Hall of Parliament House, Canberra. In January 2006, it was announced by the Department of Parliamentary Services that the document had been revalued down from A$40m to A$15m.

Only one copy (a 1297 copy with the royal seal of Edward I) is in private hands; it was held by the Brudenell family, earls of Cardigan, who had owned it for five centuries, before being sold to the Perot Foundation in 1984. This copy, having been on long-term loan to the US National Archives, was auctioned at Sotheby's New York on 18 December 2007; The Perot Foundation sold it in order to "have funds available for medical research, for improving public education and for assisting wounded soldiers and their families."[41] It fetched US$21.3 million,[42] It was bought by David Rubenstein of The Carlyle Group,[43] who after the auction said, "I thought it was very important that the Magna Carta stay in the United States and I was concerned that the only copy in the United States might escape as a result of this auction." Rubenstein's copy is on permanent loan to the National Archives in Washington, DC.[44]

Participant list

Barons, Bishops and Abbots who were party to Magna Carta.[45]

Barons

The 25 Surety Barons for the enforcement of Magna Carta:

- William d'Aubigny, Lord of Belvoir Castle.

- Roger Bigod, Earl of Norfolk and Suffolk.

- Hugh Bigod, Heir to the Earldoms of Norfolk and Suffolk.

- Henry de Bohun, Earl of Hereford.

- Richard de Clare, Earl of Hertford.

- Gilbert de Clare, heir to the earldom of Hertford.

- John FitzRobert, Lord of Warkworth Castle.

- Robert Fitzwalter, Lord of Dunmow Castle.

- William de Fortibus, Earl of Albemarle.

- William Hardel, **Mayor of the City of London.

- William de Huntingfield, Sheriff of Norfolk and Suffolk.

- John de Lacy, Lord of Pontefract Castle.

- William de Lanvallei, Lord of Standway Castle.

- William Malet, Sheriff of Somerset and Dorset.

- Geoffrey de Mandeville, Earl of Essex and Gloucester.

- William Marshall Jr, heir to the earldom of Pembroke.

- Roger de Montbegon, Lord of Hornby Castle, Lancashire.

- Richard de Montfichet, Baron.

- William de Mowbray, Lord of Axholme Castle.

- Richard de Percy, Baron.

- Saire/Saher de Quincy, Earl of Winchester.

- Robert de Roos, Lord of Hamlake Castle.

- Geoffrey de Saye, Baron.

- Robert de Vere, heir to the earldom of Oxford.

- Eustace de Vesci, Lord of Alnwick Castle.

Bishops

These bishops being witnesses (mentioned by the King as his advisers in the decision to sign the Charter):

- Stephen Langton, Archbishop of Canterbury, Cardinal of the Holy Roman Church,

- Henry de Loundres, Archbishop of Dublin

- E., Bishop of London

- Jocelin of Wells, Bishop of Bath and Wells

- Peter des Roches, Bishop of Winchester

- Hugh de Wells, Bishop of Lincoln

- Herbert Poore (aka "Robert"), Bishop of Salisbury

- W., Bishop of Rochester,

- Walter de Gray, Bishop of Worcester

- Geoffrey de Burgo, Bishop of Ely

- Hugh de Mapenor, Bishop of Hereford

- Richard Poore, Bishop of Chichester (brother of Herbert/Robert above)

- W., Bishop of Exeter

Abbots

These abbots being witnesses: