Karate

| |

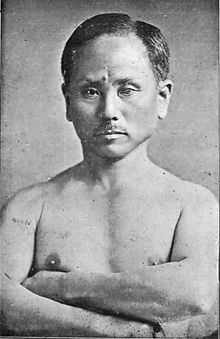

Hanashiro Chōmo | |

| Also known as | Karate-dō (空手道) |

|---|---|

| Focus | Striking |

| Hardness | full contact to non contact |

| Country of origin | |

| Creator | Sakukawa Kanga; Matsumura Sōkon; Itosu Ankō; Arakaki Seishō; Higaonna Kanryō; Gichin Funakoshi; Motobu Chōki |

| Parenthood | Chinese martial arts, indigenous martial arts of Ryukyu Islands (Naha-te, Shuri-te, Tomari-te)[1][2] |

| Olympic sport | Not voted in 2005 (for 2012) or in 2009 (for 2016) |

Karate (空手) (Japanese pronunciation: [kaɽate] , English: /kəˈrɑːtiː/) is a martial art developed in the Ryukyu Islands in what is now Okinawa, Japan. It was developed from indigenous fighting methods called te or tote (手, literally "China hand"; Tii in Okinawan) and Chinese kenpō.[1][2] Karate is a striking art using punching, kicking, knee and elbow strikes, and open-handed techniques such as knife-hands. Grappling, locks, restraints, throws, and vital point strikes are taught in some styles.[3] A karate practitioner is called a karateka (空手家).

Karate was developed in the Ryukyu Kingdom prior to its 19th century annexation by Japan. It was brought to the Japanese mainland in the early 20th century during a time of cultural exchanges between the Japanese and the Ryukyuans. In 1922 the Japanese Ministry of Education invited Gichin Funakoshi to Tokyo to give a karate demonstration. In 1924 Keio University established the first university karate club in Japan and by 1932, major Japanese universities had karate clubs.[4] In this era of escalating Japanese militarism,[5] the name was changed from 唐手 ("Chinese hand") to 空手 ("empty hand") – both of which are pronounced karate – to indicate that the Japanese wished to develop the combat form in Japanese style.[6] After the Second World War, Okinawa became an important United States military site and karate became popular among servicemen stationed there.[7]

The martial arts movies of the 1960s and 1970s served to greatly increase its popularity and the word karate began to be used in a generic way to refer to all striking-based Oriental martial arts.[8] Karate schools began appearing across the world, catering to those with casual interest as well as those seeking a deeper study of the art.

Shigeru Egami, Chief Instructor of Shotokan Dojo, opined "that the majority of followers of karate in overseas countries pursue karate only for its fighting techniques...Movies and television...depict karate as a mysterious way of fighting capable of causing death or injury with a single blow...the mass media present a pseudo art far from the real thing."[9] Shoshin Nagamine said "Karate may be considered as the conflict within oneself or as a life-long marathon which can be won only through self-discipline, hard training and one's own creative efforts." [10]

For many practitioners, karate is a deeply philosophical practice. Karate-do teaches ethical principles and can have spiritual significance to its adherents. Gichin Funakoshi ("Father of Modern Karate") titled his autobiography Karate-Do: My Way of Life in recognition of the transforming nature of karate study. Today karate is practiced for self-perfection, for cultural reasons, for self-defense and as a sport. In 2005, in the 117th IOC (International Olympic Committee) voting, karate did not receive the necessary two thirds majority vote to become an Olympic sport.[11] Web Japan (sponsored by the Japanese Ministry of Foreign Affairs) claims there are 50 million karate practitioners worldwide.[12]

History

Okinawa

Karate began as a common fighting system known as "China Hand", te (Okinawan: ti) among the Pechin class of the Ryukyuans, after trade relationships were established with the Ming dynasty of China by King Satto of Chūzan in 1372, some forms of Chinese martial arts were introduced to the Ryukyu Islands by the visitors from China, particularly Fujian Province. A large group of Chinese families moved to Okinawa around 1392 for the purpose of cultural exchange, where they established the community of Kumemura and shared their knowledge of a wide variety of Chinese arts and sciences, including the Chinese martial arts. The political centralization of Okinawa by King Shō Hashi in 1429 and the 'Policy of Banning Weapons,' enforced in Okinawa after the invasion of the Shimazu clan in 1609, are also factors that furthered the development of unarmed combat techniques in Okinawa.[2]

There were few formal styles of te, but rather many practitioners with their own methods. One surviving example is the Motobu-ryū school passed down from the Motobu family by Seikichi Uehara.[13] Early styles of karate are often generalized as Shuri-te, Naha-te, and Tomari-te, named after the three cities from which they emerged.[14] Each area and its teachers had particular kata, techniques, and principles that distinguished their local version of te from the others.

Members of the Okinawan upper classes were sent to China regularly to study various political and practical disciplines. The incorporation of empty-handed Chinese Kung Fu into Okinawan martial arts occurred partly because of these exchanges and partly because of growing legal restrictions on the use of weaponry. Traditional karate kata bear a strong resemblance to the forms found in Fujian martial arts such as Fujian White Crane, Five Ancestors, and Gangrou-quan (Hard Soft Fist; pronounced "Gōjūken" in Japanese).[15] Further influence came from Southeast Asia— particularly Sumatra, Java, and Melaka[citation needed]. Many Okinawan weapons such as the sai, tonfa, and nunchaku may have originated in and around Southeast Asia.

Sakukawa Kanga (1782–1838) had studied pugilism and staff (bo) fighting in China (according to one legend, under the guidance of Kosokun, originator of kusanku kata). In 1806 he started teaching a fighting art in the city of Shuri that he called "Tudi Sakukawa," which meant "Sakukawa of China Hand." This was the first known recorded reference to the art of "Tudi," written as 唐手. Around the 1820s Sakukawa's most significant student Matsumura Sōkon (1809–1899) taught a synthesis of te (Shuri-te and Tomari-te) and Shaolin (Chinese 少林) styles. Matsumura's style would later become the Shōrin-ryū style.

Grandfather of Modern Karate

Matsumura taught his art to Itosu Ankō (1831–1915) among others. Itosu adapted two forms he had learned from Matsumara. These are kusanku and chiang nan[citation needed]. He created the ping'an forms ("heian" or "pinan" in Japanese) which are simplified kata for beginning students. In 1901 Itosu helped to get karate introduced into Okinawa's public schools. These forms were taught to children at the elementary school level. Itosu's influence in karate is broad. The forms he created are common across nearly all styles of karate. His students became some of the most well known karate masters, including Gichin Funakoshi, Kenwa Mabuni, and Motobu Chōki. Itosu is sometimes referred to as "the Grandfather of Modern Karate."[16]

In 1881 Higaonna Kanryō returned from China after years of instruction with Ryu Ryu Ko and founded what would become Naha-te. One of his students was the founder of Gojū-ryū, Chōjun Miyagi. Chōjun Miyagi taught such well-known karateka as Seko Higa (who also trained with Higaonna), Meitoku Yagi, Miyazato Ei'ichi, and Seikichi Toguchi, and for a very brief time near the end of his life, An'ichi Miyagi (a teacher claimed by Morio Higaonna).

In addition to the three early te styles of karate a fourth Okinawan influence is that of Kanbun Uechi (1877–1948). At the age of 20 he went to Fuzhou in Fujian Province, China, to escape Japanese military conscription. While there he studied under Shushiwa. He was a leading figure of Chinese Nanpa Shorin-ken at that time.[17] He later developed his own style of Uechi-ryū karate based on the Sanchin, Seisan, and Sanseiryu kata that he had studied in China.[18]

Japan

This section needs additional citations for verification. (May 2010) |

Kanken Toyama, Hironori Ohtsuka, Takeshi Shimoda, Gichin Funakoshi, Motobu Chōki, Kenwa Mabuni, Genwa Nakasone, and Shinken Taira (from left to right)

Gichin Funakoshi, founder of Shotokan karate, is generally credited with having introduced and popularized karate on the main islands of Japan. In addition many Okinawans were actively teaching, and are thus also responsible for the development of karate on the main islands. Funakoshi was a student of both Asato Ankō and Itosu Ankō (who had worked to introduce karate to the Okinawa Prefectural School System in 1902). During this time period,prominent teachers who also influenced the spread of karate in Japan included Kenwa Mabuni, Chōjun Miyagi, Motobu Chōki, Kanken Tōyama, and Kanbun Uechi. This was a turbulent period in the history of the region. It includes Japan's annexation of the Okinawan island group in 1872, the First Sino-Japanese War (1894–1895), the Russo-Japanese War (1904–1905), the annexation of Korea, and the rise of Japanese militarism (1905–1945).

Japan was invading China at the time, and Funakoshi knew that the art of Tang/China hand would not be accepted; thus the change of the art's name to "way of the empty hand." The dō suffix implies that karatedō is a path to self knowledge, not just a study of the technical aspects of fighting. Like most martial arts practiced in Japan, karate made its transition from -jutsu to -dō around the beginning of the 20th century. The "dō" in "karate-dō" sets it apart from karate-jutsu, as aikido is distinguished from aikijutsu, judo from jujutsu, kendo from kenjutsu and iaido from iaijutsu.

Founder of Shotokan Karate

Funakoshi changed the names of many kata and the name of the art itself (at least on mainland Japan), doing so to get karate accepted by the Japanese budō organization Dai Nippon Butoku Kai. Funakoshi also gave Japanese names to many of the kata. The five pinan forms became known as heian, the three naihanchi forms became known as tekki, seisan as hangetsu, Chintō as gankaku, wanshu as empi, and so on. These were mostly political changes, rather than changes to the content of the forms, although Funakoshi did introduce some such changes. Funakoshi had trained in two of the popular branches of Okinawan karate of the time, Shorin-ryū and Shōrei-ryū. In Japan he was influenced by kendo, incorporating some ideas about distancing and timing into his style. He always referred to what he taught as simply karate, but in 1936 he built a dojo in Tokyo and the style he left behind is usually called Shotokan after this dojo.

The modernization and systemization of karate in Japan also included the adoption of the white uniform that consisted of the kimono and the dogi or keikogi—mostly called just karategi—and colored belt ranks. Both of these innovations were originated and popularized by Jigoro Kano, the founder of judo and one of the men Funakoshi consulted in his efforts to modernize karate.

In 1922, Hironori Ohtsuka attended the Tokyo Sports Festival, where he saw Funakoshi's karate. Ohtsuka was so impressed with this that he visited Funakoshi many times during his stay. Funakoshi was, in turn, impressed by Ohtsuka's enthusiasm and determination to understand karate, and agreed to teach him. In the following years, Ohtsuka set up a medical practice dealing with martial arts injuries. His prowess in martial arts led him to become the Chief Instructor of Shindō Yōshin-ryū jujutsu at the age of 30, and an assistant instructor in Funakoshi's dojo.

By 1929, Ohtsuka was registered as a member of the Japan Martial Arts Federation. Okinawan karate at this time was only concerned with kata. Ohtsuka thought that the full spirit of budō, which concentrates on defence and attack, was missing, and that kata techniques did not work in realistic fighting situations. He experimented with other, more combative styles such as judo, kendo, and aikido. He blended the practical and useful elements of Okinawan karate with traditional Japanese martial arts techniques from jujitsu and kendo, which led to the birth of kumite, or free fighting, in karate. Ohtsuka thought that there was a need for this more dynamic type of karate to be taught, and he decided to leave Funakoshi to concentrate on developing his own style of karate: Wadō-ryū. In 1934, Wadō-ryū karate was officially recognized as an independent style of karate. This recognition meant a departure for Ohtsuka from his medical practice and the fulfilment of a life's ambition—to become a full-time martial artist.

Ohtsuka's personalized style of Karate was officially registered in 1938 after he was awarded the rank of Renshi-go. He presented a demonstration of Wadō-ryū karate for the Japan Martial Arts Federation. They were so impressed with his style and commitment that they acknowledged him as a high-ranking instructor. The next year the Japan Martial Arts Federation asked all the different styles to register their names; Ohtsuka registered the name Wadō-ryū. In 1944, Ohtsuka was appointed Japan's Chief Karate Instructor.

A new form of karate called Kyokushin was formally founded in 1957 by Masutatsu Oyama (who was born a Korean, Choi Yeong-Eui 최영의). Kyokushin is largely a synthesis of Shotokan and Gōjū-ryū. It teaches a curriculum that emphasizes aliveness, physical toughness, and full contact sparring. Because of its emphasis on physical, full-force sparring, Kyokushin is now often called "full contact karate", or "Knockdown karate" (after the name for its competition rules). Many other karate organizations and styles are descended from the Kyokushin curriculum.

The World Karate Federation recognizes these styles of karate in its kata list [19]

The World Union of Karate-do Federations (WUKF) recognizes these styles of karate in its kata list.[20]

Many schools would be affiliated with, or heavily influenced by, one or more of these styles.

Practice

Karate can be practiced as an art (budō), as a sport, as a combat sport, or as self defense training. Traditional karate places emphasis on self development (budō).[21] Modern Japanese style training emphasizes the psychological elements incorporated into a proper kokoro (attitude) such as perseverance, fearlessness, virtue, and leadership skills. Sport karate places emphasis on exercise and competition. Weapons (kobudō) is important training activity in some styles.

Karate training is commonly divided into kihon (basics or fundamentals), kata (forms), and kumite (sparring).

Kihon

Karate styles place varying importance on kihon. Typically this is performance in unison of a technique or a combination of techniques by a group of karateka. Kihon may also be prearranged drills in smaller groups or in pairs.

Kata

Kata (型:かた) means literally "shape" or "model." Kata is a formalized sequence of movements which represent various offensive and defensive postures. These postures are based on idealized combat applications.

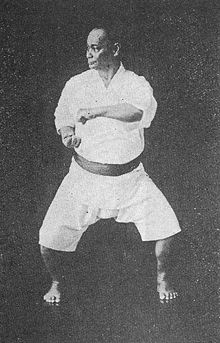

Some kata use low and wide stances. This practice develops leg strength, correct posture, and gracefulness. Vigorous arm movements enhance cardiovascular fitness and upper body strength. Kata vary in number of movements and difficulty. The longer kata require the karateka to learn many complex movements. Diligent training and correct mindfulness lead to real understanding of combat principles.

Physical routines were a logical way to preserve this type of knowledge. The various moves have multiple interpretations and applications. Because the applicability for actual self-defense is so flexible there is no definitively correct way to interpret all kata. That is why only high ranking practitioners are qualified to judge adequate form for their own style. Some of the criteria for judging the quality of a performance are: Absence of missteps; correct beginning and especially ending; crispness and smoothness; correct speed and power; confidence; and knowledge of application. Kata with the same name are often performed differently in other styles of karate. Kata are taught with minor variations among schools of the same style. Even the same instructor will teach a particular kata slightly differently as the years pass.

To attain a formal rank the karateka must demonstrate competent performance of specific required kata for that level. The Japanese terminology for grades or ranks is commonly used. Requirements for examinations vary among schools.

Kumite

Sparring in Karate is called kumite (組手:くみて). It literally means "meeting of hands." Kumite is practiced both as a sport and as self-defense training. Levels of physical contact during sparring vary considerably. Full contact karate has several variants. Knockdown karate (such as Kyokushin) uses full power techniques to bring an opponent to the ground. In Kickboxing variants ( for example K-1), the preferred win is by knockout. Sparring in armour (bogu kumite) allows full power techniques with some safety. Sport kumite in many international competition under the World Karate Federation is free or structured with light contact or semi contact and points are awarded by a referee.

In structured kumite (Yakusoku – prearranged), two participants perform a choreographed series of techniques with one striking while the other blocks. The form ends with one devastating technique (Hito Tsuki).

In free sparring (Jiyu Kumite), the two participants have a free choice of scoring techniques. The allowed techniques and contact level are primarily determined by sport or style organization policy, but might be modified according to the age, rank and sex of the participants. Depending upon style, take-downs, sweeps and in some rare cases even time-limited grappling on the ground are also allowed.

Free sparring is performed in a marked or closed area. The bout runs for a fixed time (2 to 3 minutes.) The time can run continuously (Iri Kume) or be stopped for referee judgment. In light contact or semi contact kumite, points are awarded based on the criteria: good form, sporting attitude, vigorous application, awareness/zanshin, good timing and correct distance. In full contact karate kumite, points are based on the results of the impact, rather than the formal appearance of the scoring technique.

Dojo Kun

In the bushidō tradition dojo kun is a set of guidelines for karateka to follow. These guidelines apply both in the dojo (training hall) and in everyday life.

Conditioning

Okinawan karate uses supplementary training known as hojo undo. This utilizes simple equipment made of wood and stone. The makiwara is a striking post. The nigiri game is a large jar used for developing grip strength. These supplementary exercises are designed to increase strength, stamina, speed, and muscle coordination.[22] Sport Karate emphasises aerobic exercise, anaerobic exercise, power, agility, flexibility, and stress management.[23] All practices vary depending upon the school and the teacher.

Sport

Gichin Funakoshi (船越 義珍) said, "There are no contests in karate."[24] In pre–World War II Okinawa, kumite was not part of karate training.[25] Shigeru Egami relates that, in 1940, some karateka were ousted from their dojo because they adopted sparring after having learned it in Tokyo.[26]

Karate is divided into style organizations. These organizations sometimes cooperate in non-style specific sport karate organizations or federations. Examples of sport organizations are AAKF/ITKF, AOK, TKL, AKA, WKF, NWUKO, WUKF and WKC.[27] Organizations hold competitions (tournaments) from local to international level. Tournaments are designed to match members of opposing schools or styles against one another in kata, sparring and weapons demonstration. They are often separated by age, rank and sex with potentially different rules or standards based on these factors. The tournament may be exclusively for members of a particular style (closed) or one in which any martial artist from any style may participate within the rules of the tournament (open).

The World Karate Federation (WKF) is the largest sport karate organization and is recognized by the International Olympic Committee (IOC) as being responsible for karate competition in the Olympic games. The WKF has developed common rules governing all styles. The national WKF organizations coordinate with their respective National Olympic Committees.

Karate does not have 2012 Olympic status. In the 117th IOC Session (July 2005), karate received more than half of the votes, but not the two-thirds majority needed to become an official Olympic sport.

WKF karate competition has two disciplines: sparring (kumite) and forms (kata) Competitors may enter either as individuals or as part of a team. Evaluation for kata and kobudō is performed by a panel of judges, whereas sparring is judged by a head referee, usually with assistant referees at the side of the sparring area. Sparring matches are typically divided by weight, age, gender, and experience.

WKF only allows membership through one national organization/federation per country to which clubs may join. The World Union of Karate-do Federations (WUKF)[28] offers different styles and federations a world body they may join, without having to compromise their style or size. The WUKF accepts more than one federation or association per country.

Sport organizations use different competition rule systems. Light contact rules are used by the WKF, WUKO, IASK and WKC. Full contact karate rules used by Kyokushinkai, Seidokaikan and other organizations. Bogu kumite (full contact with protective padding) rules are used in the All Japan Koshiki Karate-Do Federation organization.[29] Shinkaratedo Federation use boxing gloves.[30] Within the United States, rules may be under the jurisdiction of state sports authorities, such as the boxing commission.

Rank

In 1924 Gichin Funakoshi, founder of Shotokan Karate, adopted the Dan system from judo founder Jigoro Kano[31] using a rank scheme with a limited set of belt colors. Other Okinawan teachers also adopted this practice. In the Kyū/Dan system the beginner grades start with a higher numbered kyū (e.g., 10th Kyū or Jukyū) and progress toward a lower numbered kyū. The Dan progression continues from 1st Dan (Shodan, or 'beginning dan') to the higher dan grades. Kyū-grade karateka are referred to as "color belt" or mudansha ("ones without dan/rank"). Dan-grade karateka are referred to as yudansha (holders of dan/rank). Yudansha typically wear a black belt. Requirements of rank differ among styles, organizations, and schools. Kyū ranks stress stance, balance, and coordination. Speed and power are added at higher grades.

Minimum age and time in rank are factors affecting promotion. Testing consists of demonstration of techniques before a panel of examiners. This will vary by school, but testing may include everything learned at that point, or just new information. The demonstration is an application for new rank (shinsa) and may include kata, bunkai, self-defense, routines, tameshiwari (breaking), and/or kumite (sparring). Black belt testing may also include a written examination.

Dishonest practice

Due to the popularity of martial arts, both in mass media and reality, a large number of disreputable, fraudulent, or misguided teachers and schools have arisen, approximately over the last 40 years. Commonly referred to as a "McDojo"[32] or a "Black Belt Mill," these schools are commonly headed by martial artists of either dubious skill or business ethics.

Philosophy

Gichin Funakoshi interpreted the "kara" of Karate-dō to mean "to purge oneself of selfish and evil thoughts. For only with a clear mind and conscience can the practitioner understand the knowledge which he receives." Funakoshi believed that one should be "inwardly humble and outwardly gentle." Only by behaving humbly can one be open to Karate's many lessons. This is done by listening and being receptive to criticism. He considered courtesy of prime importance. He said that "Karate is properly applied only in those rare situations in which one really must either down another or be downed by him." Funakoshi did not consider it unusual for a devotee to use Karate in a real physical confrontation no more than perhaps once in a lifetime. He stated that Karate practitioners must "never be easily drawn into a fight." It is understood that one blow from a real expert could mean death. It is clear that those who misuse what they have learned bring dishonor upon themselves. He promoted the character trait of personal conviction. In "time of grave public crisis, one must have the courage...to face a million and one opponents." He taught that indecisiveness is a weakness.[33]

Etymology

Karate was originally written as "Chinese hand" (唐手 literally "Tang dynasty hand") in kanji. It was later changed to a homophone meaning empty hand (空手). The original use of the word "karate" in print is attributed to Ankō Itosu; he wrote it as "唐手". The Tang Dynasty of China ended in AD 907, but the kanji representing it remains in use in Japanese language referring to China generally, in such words as "唐人街" meaning Chinatown. Thus the word "karate" was originally a way of expressing "martial art from China."

Since there are no written records it is not known definitely whether the kara in karate was originally written with the character 唐 meaning China or the character 空 meaning empty. During the time when admiration for China and things Chinese was at its height in the Ryūkyūs it was the custom to use the former character when referring to things of fine quality. Influenced by this practice, in recent times karate has begun to be written with the character 唐 to give it a sense of class or elegance.

— Gishin Funakoshi[34]

The first documented use of a homophone of the logogram pronounced kara by replacing the Chinese character meaning "Tang Dynasty" with the character meaning "empty" took place in Karate Kumite written in August 1905 by Chōmo Hanashiro (1869–1945). Sino–Japanese relations have never been very good, and especially at the time of the Japanese invasion of Manchuria, referring to the Chinese origins of karate was considered politically incorrect.[35]

In 1933, the Okinawan art of karate was recognized as a Japanese martial art by the Japanese Martial Arts Committee known as the "Butoku Kai". Until 1935, "karate" was written as "唐手" (Chinese hand). But in 1935, the masters of the various styles of Okinawan karate conferred to decide a new name for their art. They decided to call their art "karate" written in Japanese characters as "空手" (empty hand).[14]

Another nominal development is the addition of dō (道:どう) to the end of the word karate. Dō is a suffix having numerous meanings including road, path, route, and way. It is used in many martial arts that survived Japan's transition from feudal culture to modern times. It implies that these arts are not just fighting systems but contain spiritual elements when promoted as disciplines. In this context dō is usually translated as "the way of ___". Examples include aikido, judo, kyudo, and kendo. Thus karatedō is more than just empty hand techniques. It is "The Way Of The Empty Hand".

Karate and its influence outside Japan

Canada

Karate began in Canada in the 1930s and 1940s as Japanese people immigrated to the country. Karate was practised quietly without a large amount of organization. During the Second World War, many Japanese-Canadian families were moved to the interior of British Columbia. Masaru Shintani, at the age of 13, began to study Shorin-Ryu karate in the Japanese camp under Kitigawa. In 1956 after 9 years of training with Kitigawa, Shintani travelled to Japan and met Hironori Otsuka (Wado Ryu). In 1958 Otsuka invited Shintani to join his organization Wado Kai, and in 1969 he asked Shintani to officially call his style Wado.[36]

In Canada during this same time, karate was also introduced by Masami Tsuruoka who had studied in Japan in the 1940s under Tsuyoshi Chitose.[37] In 1954 Tsuruoka initiated the first karate competition in Canada and laid the foundation for the National Karate Association.[37]

In the late 1950s Shintani moved to Ontario and began teaching karate and judo at the Japanese Cultural Centre in Hamilton. In 1966 he began (with Otsuka's endorsement) the Shintani Wado Kai Karate Federation. During the 1970s Otsuka appointed Shintani the Supreme Instructor of Wado Kai in North America. In 1979, Otsuka publicly promoted Shintani to hachidan (8th dan) and privately gave him a kudan certificate (9th dan), which was revealed by Shintani in 1995. Shintani and Otsuka visited each other in Japan and Canada several times, the last time in 1980 two years prior to Otsuka's death. Shintani died May 7, 2000.[36]

Korea

Due to past conflict between Korea and Japan, most notably during the Japanese occupation in the 20th century, the influence of karate in Korea is a contentious issue. From 1910 until 1939, many Koreans migrated to Japan[38] and were exposed to Japanese martial arts. After regaining independence from Japan, many Korean martial arts schools were founded by masters with training in Chinese, Japanese, and Korean martial arts.

Won Kuk Lee, a Korean student of Funakoshi founded the first Korean Karate school in 1944-5 called Chung Do Kwan. Similar "Kwan" schools cropped up in the late 1940s. These martial arts were initially called Tang Soo Do and eventually renamed Taekwondo by Choi Hong Hi with a committee of Korean masters. Choi was a significant figure in taekwondo history, who studied Korean Karate under these early masters and worked toward unifying a Korean national martial art. Karate also provided an important comparative model for the early founders of taekwondo in the formalization of their art including kata and the belt rank system. The early forms (Kata) followed the choreography of the Japanese Kata. Eventually original Korean forms (poomse, hyung) were developed by individual schools and associations. Although WTF (Olympic) and ITF forms are prevalent throughout the taekwondo world, there are still many "traditional" taekwondo and tang soo do schools where Japanese kihon and kata are regularly practiced as they were originally conveyed to Won Kuk Lee and his contemporaries from Master Funakoshi.

Soviet Union

Karate appeared in the Soviet Union in the mid-1960s, during Nikita Khrushchev's policy of improved international relations. The first Shotokan clubs were opened in Moscow's universities.[39] In 1973, however, the government banned karate—together with all other foreign martial arts—endorsing only the Soviet martial art of sambo. Failing to suppress these uncontrolled groups, the USSR's Sport Committee formed the Karate Federation of USSR in December 1978.[39] On 17 May 1984, the Soviet Karate Federation was disbanded and all karate became illegal again. In 1989, karate practice became legal again, but under strict government regulations, only after the dissolution of the Soviet Union in 1991 did independent karate schools resume functioning, and so federations were formed and national tournaments in authentic styles began.[40]

United Kingdom

In the 1950s and 1960s, several Japanese karate masters began to teach the art in the United Kingdom. In 1965, Tatsuo Suzuki began teaching Wadō-ryū in London. In 1966, members of the former British Karate Federation established the Karate Union of Great Britain (KUGB) under Hirokazu Kanazawa as chief instructor[41] and affiliated to JKA. Keinosuke Enoeda came to England at the same time as Kanazawa, teaching at a dojo in Liverpool. Kanazawa left the UK after 3 years and Enoeda took over. After Enoeda’s death in 2003, the KUGB elected Andy Sherry as Chief Instructor. Shortly after this, a new association split off from KUGB, JKA England.

An earlier significant split from the KUGB took place in 1991 when a group led by KUGB senior instructor Steve Cattle formed the English Shotokan Academy (ESA). The aim of this group was to follow the teachings of Taiji Kase, formerly the JKA chief instructor in Europe, who along with Hiroshi Shirai created the World Shotokan Karate-do Academy (WKSA), in 1989 in order to pursue the teaching of “Budo” karate as opposed to what he viewed as “sport karate”. Kase sought to return the practice of Shotokan Karate to its martial roots, reintroducing amongst other things open hand and throwing techniques that had been side lined as the result of competition rules introduced by the JKA. Both the ESA and the WKSA (re-named the Kase-Ha Shotokan-Ryu Karate-do Academy (KSKA) after Kase’s death in 2004) continue following this path today.

In 1975 Great Britain became the first team ever to take the World male team title from Japan after being defeated the previous year in the final.

United States

After World War II, members of the US military learned karate in Okinawa or Japan and then opened schools in the USA. In 1945 Robert Trias opened the first dojo in the United States in Phoenix, Arizona, a Shuri-ryū karate dojo. In the 1950s, Edward Kaloudis, William Dometrich (Chitō-ryū), Ed Parker (Kenpo), Cecil Patterson (Wadō-ryū), Gordon Doversola (Okinawa-te), Louis Kowlowski, Don Nagle (Isshin-ryū), George Mattson (Uechi-ryū), Paul Arel (Sankata, Kyokushin, and Kokondo) and Peter Urban (Gōjū-kai) all began instructing in the US.

Tsutomu Ohshima began studying karate while a student at Waseda University, beginning in 1948, and became captain of the university's karate club in 1952. He trained under Shotokan's founder, Gichin Funakoshi, until 1953. Funakoshi personally awarded Ohshima his sandan (3rd degree black belt) rank in 1952. In 1957 Ohshima received his godan (fifth degree black belt), the highest rank awarded by Funakoshi. This remains the highest rank in SKA. In 1952, Ohshima formalized the judging system used in modern karate tournaments. However, he cautions students that tournaments should not be viewed as an expression of true karate itself.

Ohshima left Japan in 1955 to continue his studies at UCLA. He led his first U.S. practice in 1956 and founded the first university karate club in the United States at Caltech in 1957. In 1959 he founded the Southern California Karate Association (SCKA), as additional Shotokan dojos opened. The organization was renamed Shotokan Karate of America in 1969.

In the 1960s, Jay Trombley (Gōjū-ryū), Anthony Mirakian (Gōjū-ryū), Steve Armstrong, Bruce Terrill, Richard Kim (Shorinji-ryū), Teruyuki Okazaki (Shotokan), John Pachivas, Allen Steen, Sea Oh Choi (Hapkido), Gosei Yamaguchi (Gōjū-ryū), Mike Foster (Chito-ryu/Yoshukai) and J. Pat Burleson all began teaching martial arts around the country.[42]

In 1961 Hidetaka Nishiyama, a co-founder of the JKA and student of Gichin Funakoshi, began teaching in the United States, founding afterwards the International Traditional Karate Federation (ITKF). Takayuki Mikami were sent to New Orleans by the JKA in 1963.

In 1964, Takayuki Kubota, founder of Gosoku-ryū, relocated the International Karate Association from Tokyo to California.

Seido Karate was founded by Tadashi Nakamura

In 1970 Paul Arel founded Kokondo Karate which is a sister style of Jukido Jujitsu developed in 1959. Kokondo synthesized techniques and kata from Arel's previous experience in Isshin Ryu, Sankata & Kyokushin Karate.

France

France Shotokan Karate, was created in 1964, by Tsutomu Ohshima. It is still the only organization representing Ohshima Shotokan style.

Film and popular culture

Karate spread rapidly in the West through popular culture. In 1950s popular fiction, karate was at times described to readers in near-mythical terms, and it was credible to show Western experts of unarmed combat as unaware of Eastern martial arts of this kind.[43] By the 1970s, martial arts films had formed a mainstream genre that propelled karate and other Asian martial arts into mass popularity.[44]

- The Karate Kid (1984) and its sequels The Karate Kid, Part II (1986), The Karate Kid, Part III (1989) and The Next Karate Kid (1994) are films relating the fictional story of an American adolescent's introduction into karate.[45][46]

- Chuck Norris: Karate Kommandos(1986), animated children's show, with Chuck Norris himself appearing to reveal the episode and the moral contained in the episode.

| Practitioner | Fighting style |

|---|---|

| Sonny Chiba | Gōjū-ryū and Kyokushin |

| Sean Connery | Kyokushin |

| Fumio Demura | Shitō-ryū |

| Tadashi Yamashita | Shorin-ryu |

| Dolph Lundgren | Kyokushin[47][48] |

| Jean-Claude Van Damme | Shotokan[49] |

| Michael Jai White | Kyokushin,[50] Shotokan, and Gōjū-ryū |

| Richard Norton | Gōjū-ryū |

| Cynthia Luster | Gōjū-ryū |

| Wesley Snipes | Shotokan[51] |

| Glen Murphy | Kyokushin |

Karate in mixed martial arts

Karate, although not widely used in mixed martial arts, has proved to be effective in the sport.[44][52] Various styles of karate are practiced by some MMA fighters, notably Chuck Liddell, Lyoto Machida and Georges St-Pierre. Liddell is known to have an extensive striking background in Kenpō and Koei-Kan[53] where as Lyoto Machida practices Shotokan[54] and St-Pierre Kyokushin.[55]

See also

- Comparison of karate styles

- Karate kata

- Japanese martial arts

- Okinawan martial arts

- Full contact karate

References

- ^ a b c Higaonna, Morio (1985). Traditional Karatedo Vol. 1 Fundamental Techniques. p. 17. ISBN 0-87040-595-0.

- ^ a b c d History of Okinawan Karate

- ^ Bishop, Mark (1989). Okinawan Karate. pp. 153–166. ISBN 0-7136-5666-2. Chapter 9 covers Motobu-ryu and Bugeikan, two 'ti' styles with grappling and vital point striking techniques. Page 165, Seitoku Higa: "Use pressure on vital points, wrist locks, grappling, strikes and kicks in a gentle manner to neutralize an attack."

- ^ "唐手研究会、次いで空手部の創立". Keio Univ. Karate Team. Retrieved 2010-03-14. [dead link]Template:Ja icon

- ^ Miyagi, Chojun (1993) [1934]. McCarthy, Patrick (ed.). Karate-doh Gaisetsu. p. 9. ISBN 4-900613-05-3.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|trans_title=ignored (|trans-title=suggested) (help) - ^ Draeger & Smith (1969). Comprehensive Asian Fighting Arts. p. 60. ISBN 978-0-87011-436-6.

- ^ Bishop, Mark (1999). Okinawan Karate Second Edition. p. 11. ISBN 978-0-8048-3205-2.

- ^ Dr. Gary J. Krug: the Feet of the Master: Three Stages in the Appropriation of Okinawan Karate Into Anglo-American Culture

- ^ Shigeru, Egami (1976). The Heart of Karate-Do. p. 13. ISBN 0-87011-816-1.

- ^ Nagamine, Shoshin (1976). Okinawan Karate-do. p. 47. ISBN 978-0-8048-2110-0.

- ^ News from the 117th IOC

- ^ Web Japan

- ^ Bishop, Mark (1989). Okinawan Karate. p. 154. ISBN 0-7136-5666-2. Motobu-ryū & Seikichi Uehara

- ^ a b Higaonna, Morio (1985). Traditional Karatedo Vol. 1 Fundamental Techniques. p. 19. ISBN 0-87040-595-0.

- ^ Bishop, Mark (1989). Okinawan Karate. p. 28. ISBN 0-7136-5666-2. For example Chōjun Miyagi adapted Rokkushu of White Crane into Tenshō

- ^ Patrick McCarthy, footnote #4

- ^ Kanbun Uechi history

- ^ Hokama, Tetsuhiro (2005). 100 Masters of Okinawan Karate. Okinawa: Ozata Print. p. 28.

- ^ Competition Rules. Kata and Kumite, World Karate Federation, page 25

- ^ WUKF World Union of Karate-do Federations

- ^ International Traditional Karate Federation (ITKF)

- ^ Higaonna, Morio (1985). Traditional Karatedo Vol. 1 Fundamental Techniques. p. 67. ISBN 0-87040-595-0.

- ^ Mitchell, David (1991). Winning Karate Competition. p. 25. ISBN 0-7136-3402-2.

- ^ Shigeru, Egami (1976). The Heart of Karatedo. p. 111. ISBN 0-87011-816-1.

- ^ Higaonna, Morio (1990). Traditional Karatedo Vol. 4 Applications of the Kata. p. 136. ISBN 0-87040-848-9.

{{cite book}}: Check|isbn=value: checksum (help) - ^ Shigeru, Egami (1976). The Heart of Karatedo. p. 113. ISBN 0-87011-816-1.

- ^ World Karate Confederation

- ^ WUKF – World Union of Karate-Do Federations

- ^ World Koshiki Karatedo Federation

- ^ Shinkaratedo Renmei

- ^ Hokama, Tetsuhiro (2005). 100 Masters of Okinawan Karate. Okinawa: Ozata Print. p. 20.

- ^ [1] A Chronological History of the Martial Arts: Douglas Coupland's novel Generation X, which defined McJob as "a low-pay, low prestige, low-dignity, low benefit, no-future job in the service sector," appears in paperback, and within weeks, the term "McDojo" appeared at rec.martial-arts as a description of franchise martial art schools run by people with more ego than talent.

- ^ Funakoshi, Gichin. "Karate-dō Kyohan – The Master Text" Tokyo. Kodansha International; 1973.

- ^ Funakoshi, Gishin (1988). Karate-do Nyumon. Japan. p. 24. ISBN 4-7700-1891-6. Retrieved 2010-07-15.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help)CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ What's In A Name? How the meaning of the term karate has changed, Levitz, Maurey (1998), New Paltz Karate Academy, Inc.

- ^ a b Robert, T. (2006). "no title given". Journal of Asian Martial Arts. 15 (4). this issue is not available as a back issue.

- ^ a b "Karate". The Canadian Encyclopedia – Historica-Dominion. 2010. Retrieved 2010-07-20.

- ^ Nozaki, Yoshiko. "Legal Categories, Demographic Change and Japan's Korean Residents in the Long Twentieth Century". Retrieved 2007-02-19.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ a b karate-shotokan.net

- ^ "History of Shotokan (Russian)". Retrieved 2007-05-15.

- ^ International Association of Shotokan Karate (IASK)

- ^ The Original Martial Arts Encyclopedia, John Corcoran and Emil Farkas, pgs. 170–197

- ^ For example, Ian Fleming's book Goldfinger (1959, p.91-95) describes the protagonist James Bond, an expert in unarmed combat, as utterly ignorant of Karate and its demonstrations, and describes the Korean 'Oddjob' in these terms: Goldfinger said, "Have you ever heard of Karate? No? Well that man is one of the three in the world who have achieved the Black Belt in Karate. Karate is a branch of judo, but it is to judo what a spandau is to a catapult...". Such a description in a popular novel assumed and relied upon Karate being almost unknown in the West.

- ^ a b Schneiderman, R. M. (2009-05-23). "Contender Shores Up Karate's Reputation Among U.F.C. Fans". The New York Times. Retrieved 2010-01-30.

- ^ "The Karate Generation". Newsweek. 2010-02-18.

- ^ "Jaden Smith Shines in The Karate Kid". Newsweek. 2010-06-10.

- ^ "Action Star Dolph Lundgren Talks Acting ..." Bodybuilding.com. Retrieved 2010-09-09.

- ^ "Celebrity Fitness—Dolph Lundgren". Inside Kung Fu. Retrieved 2010-11-15.

- ^ "Why is he famous?". ASK MEN. Retrieved 2010-06-15.

- ^ "Talking With…Michael Jai White". GiantLife. Retrieved 2010-06-16.

- ^ "Wesley Snipes: Action man courts a new beginning". Independent. London. 2010-06-04. Retrieved 2010-06-10.

- ^ "Lyoto Machida and the Revenge of Karate". Sherdog. Retrieved 2010-02-13.

- ^ Chuck Liddell – Biography and Profile of Chuck Liddell. Martialarts.about.com. Retrieved on 2011-04-18.

- ^ Mma & Ufc. Martialarts.about.com. Retrieved on 2011-04-18.

- ^ Wickert, Marc. "Montreal's MMA Warrior". Knucklepit.com. Retrieved 6 July 2007.