Iranian Jews

| Part of a series on |

| Jews and Judaism |

|---|

Persian Jews (also called Iranian Jews) are members of Jewish communities living in Iran and throughout the former greatest extents of the Persian Empire. Judaism is the second oldest religion still existing in Iran (after Zoroastrianism) and it has a long and varied history in the region.

Today, the largest groups of Persian Jews are found in Israel (75,000 in 1993[1] and the United States (45,000) (especially in the Los Angeles area, home to a large concentration of expatriate Iranians). By various estimates, between 11,000 and 40,000 Jews remain in Iran, mostly in Tehran, Isfahan and Hamedan.

There are also smaller communities in Western Europe, Australia, and Canada. A number of groups of Persian Jews have split off since ancient times, to the extent that they are now recognized as separate communities, such as the Bukharan Jews and Mountain Jews.

History

Persian Jews have lived in the territories of today's Iran for over 2,700 years, since the first Jewish diaspora when Shalmaneser V conquered the (Northern) Kingdom of Israel (722 BCE) and sent the Israelites into captivity at Khorasan. In 586 BCE, the Babylonians expelled large populations of Jews from Judea to the Babylonian captivity.

Jews who migrated to ancient Persia mostly lived in their own communities. The Persian Jewish communities include the ancient (and until the mid-20th century still extant) communities not only of Iran, but of parts of what is now Afghanistan, Azerbaijan, northwestern India, Kirgizstan, Pakistan, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan, and Uzbekistan.

Some of the communities have been isolated from other Jewish communities, to the extent that their classification as "Persian Jews" is a matter of linguistic or geographical convenience rather than actual historical relationship with one another. During the peak of the Persian Empire, Jews are thought to have comprised as much as 20% of the population. [7]

According to the Library of Congress Country Study on Iran: "Over the centuries the Jews of Iran became physically, culturally, and linguistically indistinguishable from the non-Jewish population. The overwhelming majority of Jews speak Persian as their mother language, and a tiny minority, Kurdish." [8].

Cyrus the Great and Jews

Three times during the 6th century BCE, the Jews (Hebrews) of the ancient Kingdom of Judah were exiled to Babylon by Nebuchadnezzar. These three separate occasions are mentioned in Jeremiah (52:28-30). The first exile was in the time of Jehoiachin in 597 BCE, when the Temple of Jerusalem was partially despoiled and a number of the leading citizens removed. After eleven years (in the reign of Zedekiah) a fresh rising of the Judaeans occurred; the city was razed to the ground, and a further deportation ensued. Finally, five years later, Jeremiah records a third captivity. After the overthrow of Babylonia by the Achaemenid Empire, Cyrus the Great gave the Jews permission to return to their native land (537 BCE), and more than forty thousand are said to have availed themselves of the privilege, (See Jehoiakim; Ezra; Nehemiah and Jews). Cyrus also allowed them to practice their religion freely (See Cyrus Cylinder) unlike the previous Assyrian and Babylonian rulers.

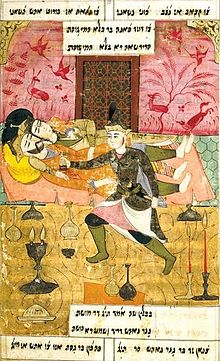

Haman and Jews

Haman was a Persian noble and vizier of the empire under Persian King Ahasuerus, generally identified as Xerxes I in 6th century BCE. According to the Book of Esther, Haman and his wife Zeresh instigated a plot to kill all the Jews of ancient Persia. The plot was foiled by Queen Esther and as a result Haman and his ten sons were hanged. Jews around the world commemorate these events in the holiday of Purim.

Parthian period

Jewish sources contain no mention of "Parthian" (Old Persian: Parthava, akin to Persia) influence; the very name Parthia does not occur, unless indeed "Parthian" is meant by "Persian" which occurs now and then. The Armenian prince Sanatroces, of the royal house of the Arsacides, is mentioned in the "Small Chronicle" as one of the successors (diadochoi) of Alexander. Among other Asiatic princes, the Roman rescript in favor of the Jews reached Arsaces as well (I Macc. xv. 22); it is not, however, specified which Arsaces. Not long after this, the Partho-Babylonian country was trodden by the army of a Jewish prince; the Syrian king, Antiochus Sidetes, marched, in company with Hyrcanus I., against the Parthians; and when the allied armies defeated the Parthians (129 BC) at the River Zab (Lycus), the king ordered a halt of two days on account of the Jewish Sabbath and Feast of Weeks. In 40 BC the Jewish puppet-king, Hyrcanus II., fell into the hands of the Parthians, who, according to their custom, cut off his ears in order to render him unfit for rulership. The Jews of Babylonia, it seems, had the intention of founding a high-priesthood for the exiled Hyrcanus, which they would have made quite independent of the Land of Israel. But the reverse was to come about: the Judeans received a Babylonian, Ananel by name, as their high priest which indicates the importance enjoyed by the Jews of Babylonia. Still in religious matters the Babylonians, as indeed the whole diaspora, were in many regards dependent upon the Land of Israel. They went on pilgrimages to Jerusalem for the festivals.

The Parthian Empire (Persian: Ashkanian) was an enduring empire that was based on a loosely configured system of vassal kings. Certainly this lack of a rigidly centralized rule over the empire had its draw backs, such as the rise of a Jewish robber-state in Nehardea (see Anilai and Asinai). Yet, the tolerance of the Arsacid dynasty was as legendry as the first Persian dynasty, the Achaemenids. There is even an account that indicates the conversion of a small number of Parthian vassal kings of Adiabene to Judaism. These instances and others show not only the tolerance of Parthian kings, but is also a testament to the extent at which the Parthians saw themselves as the heir to the preceding empire of Cyrus the Great. So protective were the Parthians of the minority over whom they ruled, that an old Jewish saying indicates, “When you see a Parthian charger tied up to a tomb-stone in the Land of Israel, the hour of the Messiah will be near”[9]. The Babylonian Jews wanted to fight in common cause with their Judean brethren against Vespasian; but it was not until the Romans waged war under Trajan against Parthia that they made their hatred felt; so, that it was in a great measure owing to the revolt of the Babylonian Jews that the Romans did not become masters of Babylonia too. Philo speaks of the large number of Jews resident in that country, a population which was no doubt considerably swelled by new immigrants after the destruction of Jerusalem. Accustomed in Jerusalem from early times to look to the east for help, and aware, as the Roman procurator Petronius was, that the Jews of Babylon could render effectual assistance, Babylonia became with the fall of Jerusalem the very bulwark of Judaism. The collapse of the Bar Kochba revolt no doubt added to the number of Jewish refugees in Babylon.

In the continuous struggles between the Parthians and the Romans, the Jews had every reason to hate the Romans, the destroyers of their sanctuary, and to side with the Parthians: their protectors. Possibly it was recognition of services thus rendered by the Jews of Babylonia, and by the Davidic house especially, that induced the Parthian kings to elevate the princes of the Exile, who till then had been little more than mere collectors of revenue, to the dignity of real princes, called Resh Galuta. Thus, then, the numerous Jewish subjects were provided with a central authority which assured an undisturbed development of their own internal affairs.

Sassanid period (226?-634?CE)

By the early Third Century, Persian influences were on the rise again. In the winter of 226 AD, Ardashir I overthrew the last Parthian king (Artabanus IV), destroyed the rule of the Arsacids, and founded the illustrious dynasty of the Sassanids. While Hellenistic influence had been felt amongst the religiously tolerant Parthians[2] [3] [4], the Sassanids intensified the Persian side of life, favored the Pahlavi language, and restored the old monotheistic religion of Zoroastrianism which became the official state religion. [5] This resulted in the suppression of other religions.[6] A priestly Zoroastrian inscription from the time of King Bahram II (276-293 CE) contains a list of religions (including Judaism, Christianity, Buddhism etc.) that Sassanid rule claimed to have "smashed".[7]

Shapur I (Shvor Malka, which is the Aramaic form of the name) was friendly to the Jews. His friendship with Shmuel gained many advantages for the Jewish community. Shapur II's mother was Jewish, and this gave the Jewish community relative freedom of religion and many advantages. He was also friend of a Babylonian rabbi in the Talmud named Raba (Talmud), Raba's friendship with Shapur II enabled him to secure a relaxation of the oppressive laws enacted against the Jews in the Persian Empire. In addition, Raba sometimes referred to his top student Abaye with the term Shvur Malka meaning "Shaput [the] King" because of his bright and quick intellect.

Of course, both Christians and Jews suffered occasional persecution; but the latter, dwelling in more compact masses in cities like Isfahan, were not exposed to such general persecutions as broke out against the more isolated Christians. Generally, this was a period of occasional persecutions for the Jews, followed by long periods of benign neglect in which Jewish learning thrived. [citation needed]

Early Islamic period (634-1255)

After the Islamic conquest of Persia, Jews, along with Christians and Zoroastrians, were assigned the status of dhimmis, inferior subjects of the Islamic empire. Dhimmis were allowed to practice their religion, but were forced to pay taxes (jizya, a poll tax, and initially also kharaj, a land tax) in favor of the Arab Muslim conquerors. Dhimmis were also required to submit to a number of social and legal disabilities; they were prohibited from bearing arms, riding horses, testifying in courts in cases involving a Muslim, and frequently required to wear clothings, clearly distinguishing them from Muslims. Although some of these restrictions were sometimes relaxed, the overall condition of inequality remained in force until the Mongol invasion.[8]

Mongol rule (1256-1318)

In 1255, Mongols led by Hulagu Khan began a charge on Persia, and in 1257 they captured Baghdad putting an end to the Abbasid caliphate. In Persia and surrounding areas, the Mongols established a division of the Mongol Empire known as Ilkhanate. Because in Ilkhanate all religions were considered equal, Mongol rulers abolished the inequality of dhimmis. One of the Ilkhanate rulers, Arghun Khan even preferred Jews and Christians for the administrative positions and appointed Sa'd al-Daula, a Jew, as his vizier. The appointed, however, provoked resentment from the Muslim clergy, and after Arghun's death in 1291, al-Daula was murdered and Persian Jews suffered a period of violent persecutions from the Muslim populace instigated by the clergy. The contemporary Christian historian Bar Hebraeus wrote that the violence committed against the Jews during that period "neither tongue can utter, nor the pen write down".[9]

Ghazan Khan's conversion to Islam in 1295 heralded for Persian Jews a pronounced turn for the worse, as they were once again relegated to the status of dhimmis. Öljeitü, Ghazan Khan's successor, destroyed many synagogues and decreed that Jews had to wear a distinctive mark on their heads; Christians endured similar persecutions. Under pressure, some Jews converted to Islam. The most famous such convert was Rashid al-Din, a physician, historian and statesman, who adopted Islam in order to advance his career at Öljeitü's court. However, in 1318 he was executed on fake charges of poisoning Öljeitü and for several days crowds had been carrying his head around his native city of Tabriz, chanting "This is the head of the Jew who abused the name of God; may God's curse be upon him!" About 100 years later, Miranshah destroyed Rashid al-Din's tomb, and his remains were reburied at the Jewish cemetery. Rashid al-Din's case illustrates a pattern that differentiated the treatment of Jewish converts in Persia from their treatment in other Muslim lands, except North Africa. In most Muslim countries, converts were welcomed and easily assimilated into the Muslim population. In Persia, however, Jewish converts were usually stigmatized on the account of their Jewish ancestry for many generations.[9][10]

Safavid and Qajar dynasties (1502-1925)

Further deterioration in the treatment of Persian Jews occurred during the reign of the Safavids who proclaimed Shi'a Islam the state religion. Shi'ism assigns great importance to the issues of ritual purity — tahara, and non-Muslims, including Jews, are deemed to be ritually unclean — najis — so that physical contact with them would require Shi'as to undertake ritual purification before doing regular prayers. Thus, Persian rulers, and to an even larger extent, the populace, sought to limit physical contact between Muslims and Jews. Jews were not allowed to attend public baths with Muslims or even to go outside in rain or snow, ostensibly because some impurity could be washed from them upon a Muslim.[11]

The reign of Shah Abbas I (1588–1629) was initially benign; Jews prospered throughout Persia and were even encouraged to settle in Isfahan, which was made a new capital. However, toward the end of his rule, the treatment of Jews became harsher; upon advice from a Jewish convert and Shi'a clergy, the shah forced Jews to wear a distinctive badge on clothing and headgear. In 1656, all Jews were expelled from Isfahan because of the common belief of their impurity and forced to convert to Islam. However, as it became known that the converts continued to practice Judaism in secret and because the treasury suffered from the loss of jizya collected from the Jews, in 1661 they were allowed to revert to Judaism, but were still required to wear a distinctive patch upon their clothings.[9]

Under Sunni Muslim Nadir Shah (1736–1747), who abolished Shi'a Islam as state religion, Jews experienced a period of relative tolerance when they were allowed to settle in the Shi'ite holy city of Mashhad. Yet, the advent of a Shi'a Qajar dynasty in 1794 brought back the earlier persecutions. In the middle of the 19th century, a European traveller wrote about the life of Persian Jews: "...they are obliged to live in a separate part of town...; for they are considered as unclean creatures... Under the pretext of their being unclean, they are treated with the greatest severity and should they enter a street, inhabited by Mussulmans, they are pelted by the boys and mobs with stones and dirt... For the same reason, they are prohibited to go out when it rains; for it is said the rain would wash dirt off them, which would sully the feet of the Mussulmans... If a Jew is recognized as such in the streets, he is subjected to the greatest insults. The passers-by spit in his face, and sometimes beat him... unmercifully... If a Jew enters a shop for anything, he is forbidden to inspect the goods... Should his hand incautiously touch the goods, he must take them at any price the seller chooses to ask for them... Sometimes the Persians intrude into the dwellings of the Jews and take possession of whatever please them. Should the owner make the least opposition in defense of his property, he incurs the danger of atoning for it with his life... If... a Jew shows himself in the street during the three days of the Katel (Muharram)..., he is sure to be murdered."[12]

The 19th century was marked by a wave of forced conversions and massacres, usually inspired by the Shi'a clergy. A representative of the Alliance Israélite Universelle, a Jewish humanitarian and educational organization, wrote from Tehran in 1894: "...every time that a priest wishes to emerge from obscurity and win a reputation for piety, he preaches war against the Jews". [13]. In 1830, all the Jews of Tabriz were massacred by having their throats slit; the same year saw a forcible conversion of the Jews of Shiraz. In 1839, Jews were massacred in Mashhad and survivors were forcibly converted. However, European travellers later reported that the Jews of Tabriz and Shiraz continued to practice Judaism in secret despite a fear of further persecutions. Jews of Barforush were forcibly converted in 1866; when they were allowed to revert to Judaism thanks to an intervention by the French and British ambassadors, a mob killed 18 Jews of Barforush, burning two of them alive.[14][15] In 1910, the Jews of Shiraz were accused of ritual murder of a Muslim girl. Muslim dwellers of the city plundered the whole Jewish quarter, the first to start looting were the soldiers sent by the local governor to defend the Jews against the enraged mob. Twelve Jews, who tried to defend their property, were killed, and many others were injured.[16] Representatives of the Alliance Israélite Universelle recorded other numerous instances of persecution and debasement of Persian Jews.[17]

Driven by persecutions, thousands of Persian Jews emigrated to Palestine in the late 19th – early 20th century.[18]

Pahlavi dynasty (1925-1979)

The Pahlavi dynasty implemented modernizing reforms, which greatly improved the life of Jews. The influence of the Shi'a clergy was weakened, and the restrictions on Jews and other religious minorities were abolished.[19] Reza Shah prohibited mass conversion of Jews and eliminated the Shi'ite concept of uncleanness of non-Muslims. Modern Hebrew was incorporated into the curriculum of Jewish schools and Jewish newspapers were published. Jews were also allowed to hold government jobs.[10] However, Jewish schools were closed in 1920s. In addition, Reza Shah sympathized with Nazi Germany, making the Jewish community fearful of possible persecutions, and the public sentiment at the time was definitely anti-Jewish,[19] as anti-Semitic propaganda intensified again.[11]

According to Charles Recknagel and Azam Gorgin of Radio Free Europe, during the reign of Reza Shah "the political and social conditions of the Jews changed fundamentally. Reza Shah prohibited mass conversion of Jews and eliminated the Shiite concept of uncleanness of non-Muslims. Modern Hebrew was incorporated into the curriculum of Jewish schools and Jewish newspapers were published. Jews were also allowed to hold government jobs. But the rise of Hitler in Germany caused anti-Semitic propaganda to intensify once more." [12]

A spike in anti-Jewish sentiment occured after the establishment of the State of Israel in 1948 and continued until 1953 due to the weakening of the central government and strengthening of the clergy in the course of political struggles between the shah and prime minister Mohammad Mossadegh. Eliz Sanasarian estimates that in 1948-1953, about one-third of Iranian Jews, most of them poor, emigrated to Israel.[20] David Littman puts the total figure of emigrants to Israel in 1948-1978 at 70,000.[18]

The reign of shah Mohammad Reza Pahlavi after the deposition of Mossadegh in 1953, was the most prosperous era for the Jews of Iran. In 1970s, only 10 percent of Iranian Jews were classified as impoverished; 80 percent were middle class and 10 percent wealthy. Although Jews accounted for only a small percentage of Iran's population, in 1979 two of the 18 members of the Iranian Academy of Sciences, 80 of the 4,000 university lecturers, and 600 of the 10,000 physicians in Iran were Jews.[20]

Islamic republic (after 1979)

At the time of the establishment of the state of Israel in 1948, there were approximately 140,000-150,000 Jews living in Iran, the historical center of Persian Jewry. Over 85% have since migrated to either Israel or the United States. At the time of the 1979 Islamic Revolution, 80,000 still remained in Iran. From then on, Jewish emigration from Iran turned into a mass exodus, as about 20,000 Jews left within several months after the Islamic Revolution.[18] On March 16, 1979, Habib Elghanian, the honorary leader of the Jewish community, was arrested on charges of "corruption", "contacts with Israel and Zionism", "friendship with the enemies of God", "warring with God and his emissaries", and "economic imperialism". He was tried by an Islamic revolutionary tribunal, sentenced to death, and executed on May 8.[18][21] According to the Library of Congress Country Study on Iran: "Unlike the Christians, the Jews have been viewed with suspicion by the government, probably because of the government's intense hostility toward Israel. Iranian Jews generally have many relatives in Israel--some 45,000 Iranian Jews emigrated from Iran to Israel between 1948 and 1977--with whom they are in regular contact. Since 1979 the government has cited mail and telephone communications as evidence of "spying" in the arrest, detention, and even execution of a few prominent Jews. Although these individual cases have not affected the status of the community as a whole, they have contributed to a pervasive feeling of insecurity among Jews regarding their future in Iran and have helped to precipitate large- scale emigration." [13]. In mid- and late 1980s, the Jewish population of Iran was estimated at 20,000-30,000. The reports put the figure at around 35,000 in mid-1990s[22] and at less than 40,000 nowadays, with around 25,000 residing in Tehran. However, Iran's Jewish community still remains the largest in the Middle East outside of Israel. [14]

Current status in Iran

Iran's Jewish community is officially recognized as a religious minority group by the government, and as with Zoroastrians, they are allocated one seat in the Iranian Parliament. Maurice Motamed has been the Jewish MP since 2000, and was re-elected again in 2004. In 2000, former Jewish MP Manuchehr Eliasi estimate there were still 30-35,000 Jews in Iran, other sources put the figure as low as 20-25,000.[23]

Iranian Jews have their own newspaper (called "Ofogh-e-Bina") with Jewish scholars performing Judaic research at Tehran's "Central Library of Jewish Association" [15]. The "Dr. Sapir Jewish Hospital" is Iran's largest charity hospital of any religious minority community in the country.[16]

-

Rabbi Beck of Neturei Karta speaks for a Persian Jewish young audience in Tehran.

-

Persian Jews are guaranteed a seat in Iran's parliament. Seen here is former president Khatami during a visit to a Tehran Jewish center. (link)

-

Leaders of Iran's Jewish communities in a meeting with visiting foreign Jews.

-

Foreign Rabbis visiting a Tehran Jewish Hospital

Jewish centers of Iran

Most Jews are nowadays living in Tehran, the capital. There are currently 100 synagogues in Iran, a quarter of them in Tehran.[17] Traditionally however, Shiraz, Hamedan, Isfahan, Nahawand, and some other cities of Iran have been home to large populations of Jews.

Jewish attractions of Iran

Almost every city of Iran has a Jewish attraction, shrine, or historical site. Prominent among these are the Esther and Mordechai and Habakkuk shrines of Hamedan, the tomb of Daniel in Susa, and the "Peighambariyeh" mausoleum in Qazvin.

There are also tombs of several outstanding Jewish scholars in Iran such as Harav Uresharga in Yazd and Hakham Mullah Moshe Halevi (Moshe-Ha-Lavi) in Kashan, which are also visited by muslim pilgrims.

-

Peighambariyeh ("the place of the prophets"), Qazvin: Here, four Jewish prophets are said to be buried. Their Arabic names are: Salam, Solum, al-Qiya, and Sohuli.

Persian Jews outside Iran

Persian Jewish communities outside Iran have suffered even greater declines than within Iran. In Afghanistan, most Persian Jews fled the country after the Soviet invasion in 1979. Only one known individual from the original community remains. [18] The community in Pakistan, where the state religion is Islam, has dwindled to less than 200. Persian Jewish communities in what is now India, on the other hand, have avoided such persecutions. Known as Baghdadi Jews, they have resided for millennia in the Rann of Kutch region as well as Bombay, most have chosen to emigrate to Israel since 1948.

In Israel, Persian Jews are classified as Mizrahim.

Languages

Most Persian Jews speak Persian, but various Jewish languages have been associated with the community over time. They include:

- Dzhidi (Judæo-Persian)

- Bukhori (Judæo-Bukharic)

- Judæo-Golpaygani

- Judæo-Kermani

- Judæo-Shirazi

- Judæo-Esfahani

- Judæo-Hamedani

- Judæo-Kashani

- Judæo-Borujerdi

- Judæo-Nehevandi

- Judæo-Khunsari

- Judæo-Yazdi

- Juhuri language (Judæo-Tat)

Terminology

Today the term Iranian Jews is mostly used to refer to Jews from the country of Iran, but in various scholarly and historical texts, the term is used to refer to Jews who speak various Iranian languages. Persians in Israel (many of whom are Jewish) are referred to as Parsim (Hebrew: פרסים meaning "Persians"). Jews in Iran (and Jewish people in general) are referred to by two common terms: Kalimi, which is considered the most proper term, and Yahudi, which is less formal.

Famous Persian Jews

- Esther

- David Alliance

- Morteza Ney Dawood

- Rashid al-Din

- Soleiman Haim

- Moshe Katsav

- Shaul Mofaz

- Benjamin Nahawandi

- Meulana Shahin Shirazi

- Maurice Motamed

See also

- Bukharan Jews

- History of the Jews in Iraq

- History of the Jews in Afghanistan

- Iran-Israel relations

- Iranian festivals

- Jews in India

- List of Asian Jews

- Islam and Judaism

- Persian people

- Purim

- Religious minorities in Iran

Notes

- ^ Template:Harvard reference. In recent years, Persian Jews have been well-assimilated into the Israeli population, so that more accurate data is hard to obtain.

- ^ [1] (see esp para's 3 and 5

- ^ [2] (see esp para. 2)

- ^ [3] (see esp para. 20)

- ^ [4]

- ^ [5] (see esp para. 5)

- ^ [6] (see esp para. 23)

- ^ Littman (1979), pp. 2–3

- ^ a b c Littman (1979), p. 3

- ^ Lewis (1984), pp. 100–101

- ^ Lewis (1984), pp. 33–34

- ^ Lewis (1984), pp. 181–183

- ^ Littman (1979), p. 10

- ^ Littman (1979), p. 4

- ^ Lewis (1984), p. 168

- ^ Littman (1979), pp. 12–14

- ^ Lewis (1984), p. 183

- ^ a b c d Littman (1979), p. 5

- ^ a b Sanasarian (2000), p. 46

- ^ a b Sanasarian (2000), p. 47

- ^ Sanasarian (2000), p. 112

- ^ Sanasarian (2000), p. 48

- ^ Report, Reuters, February 16 2000, cited from Bahá'í Library Online.

References

- Lewis, Bernard (1984). The Jews of Islam. Princeton: Princeton University Press. ISBN 0691008078.

- Littman, David (1979). "Jews Under Muslim Rule: The Case Of Persia," The Wiener Library Bulletin, Vol. XXXII

- Sanasarian, Eliz (2000). Religious Minorities in Iran. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0521770734.

External links

- History of the Iranian Jews

- TEHRAN JEWISH COMMITTEE (IRAN)

- The Jews of Iraq

- Comprehensive History of the Jews of Iran

- The invisible Iranians

- Jews in Iran Describe Life of Freedom Despite Anti-Israel Actions

- The Jewish Virtual Library's Iranian Jews page

- International Religious Freedom Report, 2001. Iran at US State Department Bureau of Democracy, Human Rights, and Labor

- Parthia (Old Persian Parthava)

- Center for Iranian Jewish Oral History

- Christian Science Monitor: "Jews in Iran Describe a Life of Freedom Despite Anti-Israel Actions by Tehran"

![]() This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Singer, Isidore; et al., eds. (1901–1906). The Jewish Encyclopedia. New York: Funk & Wagnalls.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Singer, Isidore; et al., eds. (1901–1906). The Jewish Encyclopedia. New York: Funk & Wagnalls. {{cite encyclopedia}}: Missing or empty |title= (help)