Tashkent

Toshkent

| |

|---|---|

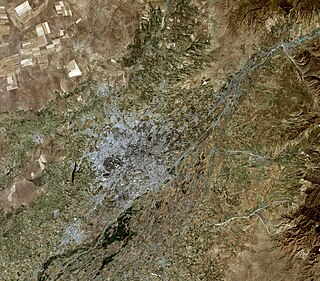

Aerial view of Tashkent | |

| Country | |

| Province | Tashkent Province |

| Settled | 5th to 3rd centuries BC |

| Government | |

| • Mayor | Rakhmonbek Usmonov |

| Area | |

| • Total | 334.8 km2 (129.3 sq mi) |

| Population (2008) | |

| • Total | 2,200,000 |

| • Density | 6,600/km2 (17,000/sq mi) |

| Time zone | UTC+5 ( ) |

| Website | http://tashkent.uz/ |

Tashkent (/ˌtæʃˈkɛnt/; Template:Lang-uz [tɒʃˈkent]; Template:Lang-ru, [tɐʂˈkʲent]; literally "Stone City") is the capital of Uzbekistan and of the Tashkent Province. The officially registered population of the city in 2008 was about 2.2 million.[1] Unofficial sources estimate the actual population may be as much as 4.45 million.[2]

History

During its long history, Tashkent has had various changes in names and political and religious affiliations.

Early history

Tashkent was settled by ancient peoples as an oasis on the Chirchik River, near the foothills of the West Tian Shan Mountains. In ancient times, this area contained Beitian, probably the summer "capital" of the Kangju confederacy.[3]

History as Chach

In pre-Islamic and early Islamic times, the town and the province were known as Chach. The Shahnameh of Ferdowsi also refers to the city as Chach. Later the town came to be known as Chachkand/Chashkand, meaning "Chach City".[citation needed]

The principality of Chach had a square citadel built here around the 5th to 3rd centuries BC, some 8 kilometres (5.0 mi) south of the Syr Darya River. By the 7th century AD, Chach had more than 30 towns and a network of over 50 canals, forming a trade center between the Sogdians and Turkic nomads. The Buddhist monk Xuánzàng 玄奘 (602/603? – 664 CE), who travelled from China to India through Central Asia, mentioned the name of the city as Zhěshí 赭時. The Chinese chronicles, Suí shū 隋書 (Book of Suí), Běi shǐ 北史 (History of Northern Dynasties) and Táng shū 唐書 (Book of Táng), mention a possession called Shí 石 or Zhěshí 赭時 with a capital of the same name since the fifth century AD [Bichurin, 1950. v. II].

In the early 8th century, the region was influenced by Islamic immigrants.

Islamic history

In the mid-seventh century, the Sassanian Persian empire fell to an Arab-lead Islamic conquest. Under the Samanid dynasty (819–999), whose founder Saman Khuda of an Zoroastrian Sassanian Persian had converted to Islam, the city came to be known as Binkath. However, the Arabs retained the old name of Chach for the surrounding region, pronouncing it al-Shash instead.

The modern Turkic name of Tashkent (City of Stone) comes from Kara-Khanid rule in the 10th century. (Tash in Turkic languages means stone. Kand, qand, kent, kad, kath, kud—all meaning a city—are derived from the Persian/Sogdian کنده kanda, meaning a town or a city. They are found in city names such as Samarkand, Yarkand, Penjikent, Khujand etc.). After the 16th century, the name evolved from Chachkand/Chashkand to Tashkand. The modern spelling of "Tashkent" reflects Russian orthography and 20th-century Soviet influence.

Mongol conquest and aftermath

The city was destroyed by Genghis Khan in 1219, although the great conqueror had found that the Khorezmshah had already sacked the city in 1214. Under the Timurids and subsequent Shaybanid dynasties the city revived, despite occasional attacks by the Uzbeks, Kazakhs, Persians, Mongols, Oirats.

Kokand khanate

In 1809, Tashkent was annexed to the Khanate of Kokand. At the time, Tashkent had a population of around 100,000 and was considered the richest city in Central Asia. It prospered greatly through trade with Russia, but chafed under Kokand’s high taxes. The Tashkent clergy also favored the clergy of Bukhara over that of Kokand. However, before the Emir of Bukhara could capitalize on this discontent, the Russian army arrived.

Tsarist period

In May, 1865, Mikhail Grigorevich Chernyayev (Cherniaev), acting against the direct orders of the tsar, and outnumbered at least 15-1 staged a daring night attack against a city with a wall 25 kilometres (16 mi) long with 11 gates and 30,000 defenders. While a small contingent staged a diversionary attack, the main force penetrated the walls, led by a Russian Orthodox priest armed only with a crucifix. Although defense was stiff, the Russians captured the city after two days of heavy fighting and the loss of only 25 dead as opposed to several thousand of the defenders (including Alimqul, the ruler of the Kokand Khanate). Chernyayev, dubbed the "Lion of Tashkent" by city elders, staged a "hearts-and-minds" campaign to win the population over. He abolished taxes for a year, rode unarmed through the streets and bazaars meeting common people, and appointed himself "Military Governor of Tashkent", recommending to Tsar Alexander II that the city be made an independent khanate under Russian protection.

The Tsar liberally rewarded Chernyayev and his men with medals and bonuses, but regarded the impulsive general as a "loose cannon", and soon replaced him with General Konstantin Petrovich von Kaufman. Far from being granted independence, Tashkent became the capital of the new territory of Russian Turkistan, with Kaufman as first Governor-General. A cantonment and Russian settlement were built across the Ankhor Canal from the old city, and Russian settlers and merchants poured in. Tashkent was a center of espionage in the Great Game rivalry between Russia and the United Kingdom over Central Asia. The Turkestan Military District was established as part of the military reforms of 1874. The Trans-Caspian Railway arrived in 1889, and the railway workers who built it settled in Tashkent as well, bringing with them the seeds of Bolshevik Revolution.

Effect of the Russian revolution

With the fall of the Russian Empire, the Russian Provisional Government removed all civil restrictions based on religion and nationality, contributing to local enthusiasm for the February Revolution. The Tashkent Soviet of Soldiers' and Workers' Deputies was soon set up, but primarily represented Russian residents, who made up about a fifth of the Tashkent population. Muslim leaders quickly set up the Tashkent Muslim Council (Tashkand Shura-yi-Islamiya) based in the old city. On 10 March 1917, there was a parade with Russian workers marching with red flags, Russian soldiers singing La Marseillaise and thousands of local Central Asians. Following various speeches, Governor-General Aleksey Kuropatkin closed the events with words "Long Live a great free Russia".[4]

The First Turkestan Muslim Conference was held in Tashkent 16–20 April 1917. Like the Muslim Council, it was dominated by the Jadid, Muslim reformers. A more conservative faction emerged in Tashkent centered around the Ulema. This faction proved more successful during the local elections of July 1917. They formed an alliance with Russian conservatives, while the Soviet became more radical. The Soviet attempt to seize power in September 1917 proved unsuccessful.[5]

In April 1918, Tashkent became the capital of the Turkestan Autonomous Soviet Socialist Republic (Turkestan ASSR). The new regime was threatened by White forces, basmachi; revolts from within, and purges ordered from Moscow. In 1930 Tashkent fell within the borders of the Uzbek SSR, and became the capital of the Uzbek SSR, displacing Samarkand.

Soviet period

The city began to industrialize in the 1920s and 1930s.

Violating the Hitler-Stalin Pact, Nazi Germany invaded the Soviet Union in June 1941. The government worked to relocate factories from western Russia and Ukraine to Tashkent to preserve the Soviet industrial capacity. This led to great increase in industry during World War II.

It also evacuated most of the German communist emigres to Tashkent.[6] The Russian population increased dramatically; evacuees from the war zones increased the total population of Tashkent to well over a million. Russians and Ukrainians eventually comprised more than half of the total residents of Tashkent.[7] Many of the former refugees stayed in Tashkent to live after the war, rather than return to former homes.

During the postwar period, the Soviet Union established numerous scientific and engineering facilities in Tashkent.

On 26 April 1966, much of the old city was destroyed by a huge earthquake (7.5 on the Richter scale). More than 300,000 residents were left homeless. Some 78,000 poorly engineered homes were destroyed,[8] mainly in the densely packed areas of the old city, where traditional adobe housing predominated.[9] The Soviet republics, and some other countries such as Finland, sent "battalions of fraternal peoples” and urban planners to help rebuild devastated Tashkent. They created a model Soviet city of wide streets planted with shade trees, parks, immense plazas for parades, fountains, monuments, and acres of apartment blocks. About 100,000 new homes were built by 1970,[8] but the builders occupied many, rather than the homeless residents of Tashkent. Further development in the following years increased the size of the city with major new developments in the Chilonzar area, north-east and south-east of the city.[8]

At the time of the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991, Tashkent was the fourth-largest city in the USSR and a center of learning in the fields of science and engineering.

Due to the 1966 earthquake and the Soviet redevelopment, little architectural heritage has survived of Tashkent's ancient history. Few structures mark its significance as a trading point on the historic Silk Road.

Capital of Uzbekistan

Tashkent is the capital of and the most cosmopolitan city in Uzbekistan. It was noted for its tree-lined streets, numerous fountains, and pleasant parks, at least until the tree-cutting campaigns initiated in 2009 by local government.[10]

Since 1991, the city has changed economically, culturally, and architecturally. New development has superseded or replaced icons of the Soviet era. The largest statue ever erected for Lenin was replaced with a globe, featuring a geographic map of Uzbekistan. Buildings from the Soviet era have been replaced with new modern buildings. The "Downtown Tashkent" district includes the 22-story NBU Bank building, an Intercontinental Hotel, the International Business Center, and the Plaza Building.

In 2007, Tashkent was named the "cultural capital of the Islamic world" by Moscow News, as the city has numerous historic mosques and significant Islamic sites, including the Isamic University.[11] Tashkent holds the earliest written Qur'an, which has been located in Tashkent since 1924.[12]

- Development of Tashkent

-

c1865

-

1913

-

1940

-

1965

-

1966 Earthquake and subsequent redevelopment

-

1981

-

2000

Geography and climate

| Tashkent | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Climate chart (explanation) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Geography

Tashkent 41°18′N 69°16′E / 41.300°N 69.267°E is situated in a well-watered plain to the west of the last Altai mountains[citation needed] on the road between Shymkent and Samarkand. Tashkent sits at the confluence of the Chirchik river and several of its tributaries and is built on deep alluvial deposits up to 15 metres (49 ft). The city is located in an active tectonic area suffering large numbers of tremors and some earthquakes. One earthquake in 1966 measured 7.5 on the Richter scale. The local time in Tashkent is UTC/GMT +5 hours.

Climate

Tashkent features a Mediterranean climate (Köppen: Csa)[14] with strong continental climate influences (Köppen: Dsa).[14] As a result Tashkent experiences short cold winters not typically associated with most Mediterranean climates and long, hot and dry summers. Winters are short and cold, covering the months of December, January and February. Most precipitation occurs during these months (frequently falling as snow). However snow cover tends to be relatively brief as the city frequently experiences warmer periods during the winter. The city experiences two peaks of precipitation in the early winter and spring. The slightly unusual precipitation pattern is partially due to its 500 m (roughly 1600 feet) altitude. Summers are long in Taskent, usually lasting from May to September. Tashkent can be extremely hot during the months of July and August. The city is also sees very little precipitation during the summer, particularly from June through September.

| Climate data for Tashkent (1981–2010) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 22.2 (72.0) |

25.7 (78.3) |

32.5 (90.5) |

36.4 (97.5) |

39.9 (103.8) |

43.0 (109.4) |

44.6 (112.3) |

43.1 (109.6) |

39.8 (103.6) |

37.5 (99.5) |

31.1 (88.0) |

27.3 (81.1) |

44.6 (112.3) |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 6.2 (43.2) |

8.1 (46.6) |

14.0 (57.2) |

22.1 (71.8) |

27.1 (80.8) |

33.2 (91.8) |

35.8 (96.4) |

34.2 (93.6) |

29.0 (84.2) |

21.4 (70.5) |

14.4 (57.9) |

8.9 (48.0) |

21.2 (70.2) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 1.8 (35.2) |

3.4 (38.1) |

9.0 (48.2) |

16.1 (61.0) |

20.3 (68.5) |

25.6 (78.1) |

27.7 (81.9) |

25.9 (78.6) |

20.9 (69.6) |

14.5 (58.1) |

9.1 (48.4) |

4.5 (40.1) |

14.9 (58.8) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | −2.6 (27.3) |

−1.4 (29.5) |

4.0 (39.2) |

10.1 (50.2) |

13.5 (56.3) |

17.9 (64.2) |

19.6 (67.3) |

17.5 (63.5) |

12.7 (54.9) |

7.5 (45.5) |

3.7 (38.7) |

0.1 (32.2) |

8.5 (47.4) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −28 (−18) |

−25.6 (−14.1) |

−16.9 (1.6) |

−6.3 (20.7) |

−1.7 (28.9) |

3.8 (38.8) |

8.2 (46.8) |

3.4 (38.1) |

0.1 (32.2) |

−11.2 (11.8) |

−22.1 (−7.8) |

−29.5 (−21.1) |

−29.5 (−21.1) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 57.8 (2.28) |

57.2 (2.25) |

64.8 (2.55) |

59.8 (2.35) |

40.9 (1.61) |

10.8 (0.43) |

3.5 (0.14) |

1.9 (0.07) |

5.9 (0.23) |

29.3 (1.15) |

41.3 (1.63) |

53.6 (2.11) |

426.8 (16.8) |

| Average precipitation days | 11.1 | 9.6 | 11.4 | 9.5 | 7.0 | 3.2 | 1.3 | 0.7 | 1.5 | 4.8 | 7.3 | 9.5 | 76.9 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 73 | 68 | 62 | 60 | 53 | 40 | 39 | 42 | 45 | 57 | 66 | 73 | 57 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 117.8 | 127.1 | 164.3 | 216.0 | 303.8 | 363.0 | 384.4 | 365.8 | 300.0 | 226.3 | 150.0 | 105.4 | 2,823.9 |

| Source: Centre of Hydrometeorological Service of Uzbekistan,[17] World Meteorological Organisation,[13] Pogoda.ru.net (record low and record high temperatures),[18] Hong Kong Observatory (mean monthly sunshine hours)[19] | |||||||||||||

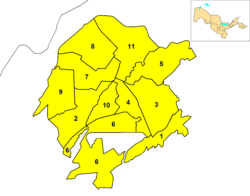

Districts

Tashkent is currently divided into the following districts (Uzbek tuman):

| Nr | District | Population (2009)[20] |

Area (km²)[20] |

Density (area/km²)[20] |

Map |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Bektemir | 27,500 | 20.5 | 1,341 | |

| 2 | Chilanzar | 217,000 | 30.0 | 7,233 | |

| 3 | Hamza | 204,800 | 33.7 | 6,077 | |

| 4 | Mirobod | 122,700 | 17.1 | 7,175 | |

| 5 | Mirzo Ulugbek | 245,200 | 31.9 | 7,687 | |

| 6 | Sergeli | 149,000 | 56.0 | 2,661 | |

| 7 | Shaykhontohur | 285,800 | 27.2 | 10,507 | |

| 8 | Olmazar | 305,400 | 34.5 | 8,852 | |

| 9 | Uchtepa | 237,000 | 28.2 | 8,404 | |

| 10 | Yakkasaray | 115,200 | 14.6 | 7,890 | |

| 11 | Yunusabad | 296,700 | 41.1 | 7,219 |

At the time of the Tsarist take over it had four districts (Uzbek daha):

- Beshyoghoch

- Kukcha

- Shaykhontokhur

- Sebzor

In 1940 it had the following districts (Russian район):

By 1981 they were reorganized into:[8]

- Bektemir

- Akmal-Ikramov (Uchtepa)

- Khamza (Hamza)

- Lenin (Mirobod)

- Kuybishev (Mirzo Ulugbek)

- Sergeli

- Oktober (Shaykhontokhur)

- Sobir Rakhimov (Olmazar)

- Chilanzar

- Frunze (Yakkasaray)

- Kirov (Yunusabad)

Main sights

Due to the destruction of most of the ancient city during the 1917 revolution and, later, to the 1966 earthquake, little remains of Tashkent's traditional architectural heritage. Tashkent is, however, rich in museums and Soviet-era monuments. They include:

- Kukeldash Madrasah. Dating back to the reign of Abdullah Khan II (1557–1598) it is currently being restored by the provincial Religious Board of Mawarannahr Moslems. There is talk of making it into a museum, but it is currently being used as a mosque.

- Chorsu Bazaar, located near the Kukeldash Madrassa. This huge open air bazaar is the center of the old town of Tashkent. Everything imaginable is for sale.

- Telyashayakh Mosque (Khast Imam Mosque). It Contains the Uthman Qur'an, considered to be the oldest extant Qur'an in the world. Dating from 655 and stained with the blood of murdered caliph, Uthman, it was brought by Timur to Samarkand, seized by the Russians as a war trophy and taken to Saint Petersburg. It was returned to Uzbekistan in 1924.[21]

- Yunus Khan Mausoleum. It is a group of three 15th century mausoleums, restored in the 19th century. The biggest is the grave of Yunus Khan, grandfather of Mughal Empire founder Babur.

- Palace of Prince Romanov. During the 19th century Grand Duke Nikolai Konstantinovich, a first cousin of Alexander III of Russia was banished to Tashkent for some shady deals involving the Russian Crown Jewels. His palace still survives in the centre of the city. Once a museum, it has been appropriated by the Ministry of Foreign Affairs.

- Alisher Navoi Opera and Ballet Theatre, built by the same architect who designed Lenin's Tomb in Moscow, Aleksey Shchusev, with Japanese prisoner of war labor in World War II. It hosts Russian ballet and opera.

- Fine Arts Museum of Uzbekistan. It contains a major collection of art from the pre-Russian period, including Sogdian murals, Buddhist statues and Zoroastrian art, along with a more modern collection of 19th and 20th century applied art, such as suzani embroidered hangings. Of more interest is the large collection of paintings "borrowed" from the Hermitage by Grand Duke Romanov to decorate his palace in exile in Tashkent, and never returned. Behind the museum is a small park, containing the neglected graves of the Bolsheviks who died in the Russian Revolution of 1917 and to Ossipov's treachery in 1919, along with first Uzbekistani President Yuldosh Akhunbabayev.

- Museum of Applied Arts. Housed in a traditional house originally commissioned for a wealthy tsarist diplomat, the house itself is the main attraction, rather than its collection of 19th and 20th century applied arts.

- History Museum the largest museum in the city. It is housed in the ex-Lenin Museum.

- Amir Timur Museum, housed in a building with brilliant blue dome and ornate interior. It houses exhibits of Timur and of President Islam Karimov. The gardens outside contain a statue of Timur on horseback, surrounded by some of the nicest gardens and fountains in the city.

- Navoi Literary Museum, commemorating Uzbekistan's adopted literary hero, Alisher Navoi, with replica manuscripts, Persian calligraphy and 15th century miniature paintings.

Russian Orthodox church in Amir Temur Square, built in 1898, was demolished in 2009, along with Soviet-time World War II memorial park and Defender of Motherland monument.[22][23][24]

City built environment

- The one of only two metro systems in Central Asia. (Almaty's is the other one.)

- The largest city square (Independence Square) in the former Soviet Union, which once held the tallest statue of Vladimir Lenin (30 metres tall) in the Soviet Union. Lenin was replaced in 1992 by a globe showing a map of Uzbekistan.

- Government, trade union and private medical and dental facilities.

- Offices of several American and European consulting firms like Ernst & Young Ltd, Deloitte & Touche, PricewaterhouseCoopers and Gravamen Fidelis and Fides LLP.[25]

Education

Most important scientific institutions of Uzbekistan, such as the Academy of Sciences of Uzbekistan, are located in Tashkent. There are several universities and institutions of higher learning:

- Tashkent Automobile & Road Construction Institute[26]

- Tashkent State Technical University

- Tashkent Institute of Architecture and Construction[27]

- International Business School "Kelajak Ilmi"[28]

- Tashkent University of Information Technologies[29]

- Westminster International University in Tashkent[30]

- National University of Uzbekistan[31]

- University of World Economy and Diplomacy

- Tashkent State Economic University

- Tashkent State Institute of Law

- Tashkent Institute of Finance

- State University of Foreign Languages

- Conservatory of Music

- Tashkent Pediatric Medical Insitute[32]

- Tashkent State Medicine Academy[33]

- Institute of Oriental Studies.

- Tashkent Islamic University[34]

- Management Development Institute of Singapore in Tashkent[35]

- Tashkent Institute of Textile and Light Industry[36]

- Tashkent Institute of Railway Transport Engineers[37]

- Management Development Institute Of Singapore in Tashkent[35]

Media

- Nine Uzbek language newspapers, four in English and nine publications in Russian

- Several television and cable television facilities, including Tashkent Tower, the tallest structure in Central Asia

Moreover, there are digital broadcasting system available in Tashkent which is unique in Central Asia.

Transportation

- Metro system

- Tashkent International Airport is the largest in the country, connecting the city to Asia, Europe and North American continents.

- Tashkent–Samarkand high-speed rail line

- Trolleybus system was closed down in 2010.

Sport

Football is the most popular sport in Tashkent, with the most prominent football clubs being FC Pakhtakor Tashkent and FC Bunyodkor, both of which compete in the Uzbek League. Footballers Peter Odemwingie and Vassilis Hatzipanagis were born in the city.

World famous cyclist Djamolidine Abdoujaparov was born in the city. Tennis player Denis Istomin was raised in the city. Akgul Amanmuradova and Iroda Tulyaganova are also notable tennis players from the city.

Gymnasts Alina Kabayeva and Alexander Shatilov were also born in the city.

Former world champion and Olympic bronze medalist sprint canoer in the K-1 500 m event Michael Kolganov was also born in Tashkent.[38]

Twin towns – sister cities

Tashkent is twinned with: Template:MultiCol

Almaty, Kazakhstan

Almaty, Kazakhstan Ankara, Turkey

Ankara, Turkey Astana, Kazakhstan

Astana, Kazakhstan Beijing, China

Beijing, China Berlin, Germany

Berlin, Germany Bishkek, Kyrgyzstan

Bishkek, Kyrgyzstan

| class="col-break " |

Cairo, Egypt

Cairo, Egypt Dnipropetrovsk, Ukraine

Dnipropetrovsk, Ukraine Istanbul, Turkey

Istanbul, Turkey Karachi, Pakistan

Karachi, Pakistan Kiev, Ukraine

Kiev, Ukraine Kortrijk, Belgium

Kortrijk, Belgium

| class="col-break " |

See also

References

- ^ Official website portal of Tashkent City

- ^ Uzbektourism.uz

- ^ Pulleyblank, Edwin G. "The Consonantal System of Old Chinese," Asia Major 9 (1963), p. 94.

- ^ Jeff Sahadeo, Russian Colonial Society in Tashkent, Indiana University Press, 2007, p188

- ^ Rex A. Wade, The Russian Revolution, 1917, Cambridge University Press, 2005

- ^ Robert K. Shirer, "Johannes R. Becher 1891–1958", Encyclopedia of German Literature, Chicago and London: Fitzroy Dearborn Publishers, 2000, by permission at Digital Commons, University of Nebraska, accessed 3 February 2013

- ^ Edward Allworth (1994), Central Asia, 130 years of Russian dominance: a historical overview, Duke University Press, p. 102. ISBN 0-8223-1521-1

- ^ a b c d Sadikov, A C. Geographical Atlas of Tashkent (Ташкент Географический Атлас) (in Russian) (2 ed.). Moscow. p. 64.

{{cite book}}:|format=requires|url=(help); Cite has empty unknown parameters:|origmonth=and|chapterurl=(help); More than one of|pages=and|page=specified (help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|origdate=ignored (|orig-date=suggested) (help) - ^ Nurtaev Bakhtiar (1998). "Damage for buildings of different type". Institute of Geology and Geophysics, Academy of Sciences of Uzbekistan. Retrieved 7 November 2008.

- ^ "Good bye the Tashkent Public Garden!". Ferghana.Ru. 23 November 2009. Retrieved 30 September 2012.

- ^ "Moscow News – World – Tashkent Touts Islamic University". Mnweekly.ru. 21 June 2007. Retrieved 6 May 2009. [dead link]

- ^ "Tashkent's hidden Islamic relic". BBC. 5 January 2006. Retrieved 16 April 2011.

- ^ a b "World Weather Information Service – Tashkent". World Meteorological Organisation. Retrieved 16 August 2012.

- ^ a b Updated Asian map of the Köppen climate classification system

- ^ Tashkent Travel. "Tashkent weather forecast". Tashkent, Uzbekistan. Retrieved 11 June 2009.

- ^ Happy-Tellus.com. "Tashkent, Uzbekistan travel information". Helsinki, Finland: Infocenter International Ltd. Retrieved 11 June 2009.

- ^ "Climate Data for Tashkent". Centre of Hydrometeorological Service. Retrieved 28 November 2012.

- ^ "Weather and Climate-The Climate of Tashkent" (in Russian). Weather and Climate. Retrieved 16 August 2012.

- ^ "Climatological Normals of Tashkent". Hong Kong Observatory. August 2010. Retrieved 18 August 2012.

- ^ a b c Template:Ru icon Statistics of the subdivisions of Tashkent

- ^ MacWilliams, Ian (5 January 2006). "Tashkent's hidden Islamic relic". BBC News. Retrieved 8 June 2010.

- ^ uznews.net, Tashkent's central park is history, 25 November 2009

- ^ Army memorial dismantled in Tashkent, 24 November 2009

- ^ Ferghana.ru, МИД России указал послу Узбекистана на обеспокоенность «Наших», 16 January 2010 Template:Ru icon

- ^ GFF.uz

- ^ TAYI.uz

- ^ TASI.uzsci.net

- ^ IBS.uz

- ^ TUIT.uz

- ^ WIUT.uz

- ^ NUU.uz

- ^ [1]

- ^ [2]

- ^ TIU.uz

- ^ a b MDIS.uz

- ^ TITLI.uz

- ^ Tashiit.uz

- ^ Sports-reference.com

Further reading

- Published in the 19th–20th century

- Henry Lansdell (1885). "Tashkend". Russian Central Asia, including Kuldja, Bokhara, Khiva and Merv. London: Sampson Low, Marston, Searle, and Rivington.

{{cite book}}: External link in|chapterurl=|chapterurl=ignored (|chapter-url=suggested) (help) - "Tashkent". The Encyclopaedia Britannica (11th ed.). New York: Encyclopaedia Britannica. 1910. OCLC 14782424.

{{cite book}}: External link in|chapterurl=|chapterurl=ignored (|chapter-url=suggested) (help) - "Tashkent". Russia with Teheran, Port Arthur, and Peking. Leipzig: Karl Baedeker. 1914. OCLC 1328163.

{{cite book}}: External link in|chapterurl=|chapterurl=ignored (|chapter-url=suggested) (help)

- Published in the 21st century

- C. Edmund Bosworth, ed. (2007). "Tashkent". Historic Cities of the Islamic World. Leiden: Koninklijke Brill.

- Stronski, Paul, Tashkent: Forging a Soviet City, 1930–1966 (Pittsburgh, University of Pittsburgh Press, 2010).

- Jeff Sahadeo, Russian Colonial Society in Tashkent, 1865–1923 (Bloomington, IN, Indiana University Press, 2010).