Eugenics

Eugenics (\yü-ˈje-niks\) is the bio-social movement which advocates practices to improve the genetic composition of a population, usually a human population.[2][3]

It is a social philosophy advocating the improvement of human hereditary traits through the promotion of higher reproduction of more desired people and traits, and reduced reproduction of less desired people and traits.[4]

History

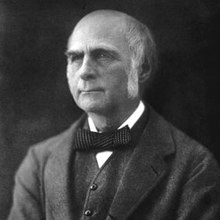

Eugenics, as a modern concept, was originally developed by Francis Galton. Galton had read his cousin Charles Darwin's theory of evolution, which sought to explain the development of plant and animal species, and desired to apply it to humans. In 1883, one year after Darwin's death, Galton gave his research a name, Eugenics.[5] Throughout its recent history, eugenics remains a controversial concept.[6] As a social movement, eugenics reached its greatest popularity in the early decades of the 20th century. At this point in time, eugenics was practiced around the world and was promoted by governments, and influential individuals and institutions. Many countries enacted[7] various eugenics policies and programs, including: genetic screening, birth control, promoting differential birth rates, marriage restrictions, segregation (both racial segregation and segregation of the mentally ill from the rest of the population), compulsory sterilization, forced abortions or forced pregnancies and genocide. Most of these policies were later regarded as coercive and/or restrictive, and now few jurisdictions implement policies that are explicitly labeled as eugenic or unequivocally eugenic in substance.

The methods of implementing eugenics varied by country; however, some of the early 20th century methods were identifying and classifying individuals and their families, including the poor, mentally ill, blind, deaf, developmentally disabled, promiscuous women, homosexuals and entire racial groups — such as the Roma and Jews — as "degenerate" or "unfit"; the segregation or institutionalisation of such individuals and groups, their sterilization, euthanasia, and in the case of Nazi Germany, their mass murder.[8] The practice of euthanasia was carried out on hospital patients in the Aktion T4 at such centres as Hartheim Castle.

Eugenics became an academic discipline at many colleges and universities, and received funding from many sources.[9] Three International Eugenics Conferences presented a global venue for eugenicists with meetings in 1912 in London, and in 1921 and 1932 in New York. Eugenic policies were first implemented in the early 1900s in the United States.[10] Later, in the 1920s and 30s, the eugenic policy of sterilizing certain mental patients was implemented in a variety of other countries, including Belgium,[11] Brazil,[12] Canada,[13] and Sweden,[14] among others. The scientific reputation of eugenics started to decline in the 1930s, a time when Ernst Rüdin used eugenics as a justification for the racial policies of Nazi Germany, and when proponents of eugenics among scientists and thinkers prompted a backlash in the public. Nevertheless, in Sweden the eugenics program continued until 1975.[14]

In addition to being practiced in a number of countries, eugenics was internationally organized through the International Federation of Eugenic Organizations. (Black 2003, p. 240) Its scientific aspects were carried on through research bodies such as the Kaiser Wilhelm Institute of Anthropology, Human Heredity, and Eugenics (Black 2003, p. 286), the Cold Spring Harbour Carnegie Institution for Experimental Evolution (Black 2003, p. 40) and the Eugenics Record Office (Black 2003, p. 45). Its political aspects involved successful advocacy for changes of law to pursue eugenic objectives; For instance, sterilization laws (e.g. U.S. sterilization laws, (Black, see Chapter 6 The United States of Sterilization)). Its moral aspects included rejection of the doctrine that all human beings are born equal and redefining morality purely in terms of genetic fitness (Black 2003, p. 237). Its racist elements included pursuit of a pure "Nordic race" or "Aryan" genetic pool and the eventual elimination of less fit races (see Black, Chapter 5 Legitimizing Raceology and Chapter 9 Mongrelization).

By the end of World War II, eugenics had been largely abandoned, having become associated with Nazi-Germany.[15][16] This country's approach to genetics and eugenics was focused on Eugen Fischer's concept of phenogenetics[17] and the Nazi twin study methods of Fischer and Otmar Freiherr von Verschuer. Both the public and some elements of the scientific community have associated eugenics with Nazi abuses, such as enforced "racial hygiene", human experimentation, and the extermination of "undesired" population groups.[citation needed], However, developments in genetic, genomic, and reproductive technologies at the end of the 20th century are raising for some people numerous new questions regarding the ethical status of eugenics, effectively creating a resurgence of interest in the subject.

The best known system of eugenics was undertaken by Nazi Germany in the 1940s, claiming that Jews and several other groups were a threat to the Germanic race and unworthy of life.

Today it is still regarded by some as a brutal movement which inflicted massive human rights violations on millions of people.[18] Some practices engaged in by people in the name of eugenics involving violations of privacy, violations of reproductive rights, attacks on reputation, violations of the right to life, to found a family, to freedom from discrimination are all today classified as violations of human rights.

The practice of negative racial aspects of eugenics, after World War II, fell within the definition of the new international crime of genocide, set out in the Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide.[19]

The Charter of Fundamental Rights of the European Union also proclaims "the prohibition of eugenic practices, in particular those aiming at selection of persons.[20]

Meanings and types

The modern field and term were first formulated by Sir Francis Galton in 1883,[21] drawing on the recent work of his half-cousin Charles Darwin.[22][23] He wrote down many of his observations and conclusions in a book, Inquiries into Human Faculty and Its Development.

The origins of the concept began with certain interpretations of Mendelian inheritance, and the theories of August Weismann.[24]

The word eugenics derives from the Greek word eu (good or well) and the suffix -genēs (born), and was coined by Sir Francis Galton in 1883 to replace the word stirpiculture (also see: Oneida stirpiculture) which he had used previously but which had come to be mocked by people of culture due to its perceived sexual overtones.[25] Galton defined eugenics as "the study of all agencies under human control which can improve or impair the racial quality of future generations".[26] Eugenics has, from the very beginning, meant many different things to many different people. Historically, the term has referred to everything from prenatal care for mothers to forced sterilization and euthanasia. To population geneticists the term has included the avoidance of inbreeding without necessarily altering allele frequencies; for example, J. B. S. Haldane wrote that "the motor bus, by breaking up inbred village communities, was a powerful eugenic agent".[27] Much debate has taken place in the past, as it does today, as to what exactly counts as eugenics.[28] Some types of eugenics deal only with perceived beneficial and/or detrimental genetic traits. These are sometimes called "pseudo-eugenics" by proponents of strict eugenics.

The term eugenics is often used to refer to movements and social policies influential during the early 20th century. In a historical and broader sense, eugenics can also be a study of "improving human genetic qualities". It is sometimes broadly applied to describe any human action whose goal is to improve the gene pool. Some forms of infanticide in ancient societies, present-day reprogenetics, preemptive abortions and designer babies have been (sometimes controversially) referred to as eugenic. Because of its normative goals and historical association with scientific racism, as well as the development of the science of genetics, the western scientific community has mostly disassociated itself from the term "eugenics", although one can find advocates of what is now known as liberal eugenics. Despite its ongoing criticism in the United States, several regions globally practice different forms of eugenics.

Eugenicists advocate specific policies that (if successful) they believe will lead to a perceived improvement of the human gene pool. Since defining what improvements are desired or beneficial is perceived by many as a cultural choice rather than a matter that can be determined objectively (e.g., by empirical, scientific inquiry), eugenics has often been deemed a pseudoscience.[29] The most disputed aspect of eugenics has been the definition of "improvement" of the human gene pool, such as what is a beneficial characteristic and what is a defect. This aspect of eugenics has historically been tainted with scientific racism.

Early eugenicists were mostly concerned with perceived intelligence factors that often correlated strongly with social class. Many eugenicists took inspiration from the selective breeding of animals (where purebreds are often strived for) as their analogy for improving human society. The mixing of races (or miscegenation) was usually considered as something to be avoided in the name of racial purity. At the time this concept appeared to have some scientific support, and it remained a contentious issue until the advanced development of genetics led to a scientific consensus that the division of the human species into unequal races is unjustifiable.[citation needed]

Eugenics has also been concerned with the elimination of hereditary diseases such as hemophilia and Huntington's disease. However, there are several problems with labeling certain factors as genetic defects. In many cases there is no scientific consensus on what constitutes a genetic defect. It is often argued that this is more a matter of social or individual choice. What appears to be a genetic defect in one context or environment may not be so in another. This can be the case for genes with a heterozygote advantage, such as sickle-cell disease or Tay-Sachs disease, which in their heterozygote form may offer an advantage against, respectively, malaria and tuberculosis. Although some birth defects are uniformly lethal, disabled persons can succeed in life. Many of the conditions early eugenicists identified as inheritable (pellagra is one such example) are currently considered to be at least partially, if not wholly, attributed to environmental conditions. Similar concerns have been raised when a prenatal diagnosis of a congenital disorder leads to abortion (see also preimplantation genetic diagnosis).

Eugenic policies have been conceptually divided into two categories. Positive eugenics is aimed at encouraging reproduction among the genetically advantaged,for example the reproduction of the intelligent, the healthy, and the successful [30] Possible approaches include financial and political stimuli, targeted demographic analyses, in vitro fertilization, egg transplants, and cloning.[31] Negative eugenics is aimed at lowering fertility among the genetically disadvantaged. Negative eugenics aimed to eliminate, through sterilisation or segregation, those deemed physically, mentally, or morally “undesirable” [30] This includes abortions, sterilization, and other methods of family planning.[31] Both positive and negative eugenics can be coercive. Abortion by fit women was illegal in Nazi Germany.[32]

Implementation methods

There are three main ways by which the methods of eugenics can be applied.[citation needed] One is mandatory eugenics or authoritarian eugenics, in which the government mandates a eugenics program. Policies and/or legislation are often seen as being coercive and restrictive. Another is promotional voluntary eugenics, in which eugenics is voluntarily practiced and promoted to the general population, but not officially mandated. This is a form of non-state enforced eugenics, using a liberal or democratic approach, which can mostly be seen in the 1900s.[33] The third is private eugenics, which is practiced voluntarily by individuals and groups, but not promoted to the general population.

Dysgenics

Research has suggested that in the modern world, the relationship between fertility and intelligence is such that those with higher intelligence have fewer children, one possible reason being more unintended pregnancies for those with lower intelligence. Several researchers have argued that the average genotypic intelligence of the United States and the world are declining which is a dysgenic effect. This has been masked by the Flynn effect for phenotypic intelligence. The Flynn effect may have ended in some developed nations, causing some to argue that phenotypic intelligence will or has started to decline.[34][35][36]

Similarly, Richard Lynn has in the book Dysgenics: Genetic Deterioration in Modern Populations argued that genetic health (due to modern health care) and genetic conscientiousness (criminals have more children than non-criminals) are declining in the modern world. This has caused some, like Lynn, to argue for voluntary eugenics.[37] Lynn and Harvey (2008) suggest that designer babies may have an important eugenic effect in the future. Initially this may be limited to wealthy couples, who may possibly travel abroad for the procedure if prohibited in their own country, and then gradually spread to increasingly larger groups. Alternatively, authoritarian states may decide to impose measures such as a licensing requirement for having a child, which would only be given to persons of a certain minimum intelligence. The Chinese one-child policy is an example of how fertility can be regulated by authoritarian means.[35]

Criticism

Doubts on genetic mutation triggered by inheritance

The first major challenge to conventional eugenics based upon genetic inheritance was made in 1915 by Thomas Hunt Morgan, who demonstrated the event of genetic mutation occurring outside of inheritance involving the discovery of the hatching of a fruit fly with white eyes from a family and ancestry of the red-eyed Drosophila melanogaster species of fruit fly.[38] Morgan claimed that this demonstrated that major genetic changes occurred outside of inheritance and that the concept of eugenics based upon genetic inheritance was, to some extent, not completely scientifically accurate.[38]

Diseases vs. traits

While the science of genetics has increasingly provided means by which certain characteristics and conditions can be identified and understood, given the complexity of human genetics, culture, and psychology there is at this point no agreed objective means of determining which traits might be ultimately desirable or undesirable. Some diseases such as sickle-cell disease and cystic fibrosis respectively confer immunity to malaria and resistance to cholera when a single copy of the recessive allele is contained within the genotype of the individual. Reducing the instance of sickle-cell disease in Africa where malaria is a common and deadly disease could indeed have extremely negative net consequences. On the other hand, genetic diseases like haemochromatosis can increase susceptibility to illness, cause physical deformities, and other dysfunctions, which provides some incentive for people to re-consider some elements of eugenics.

Ethics

A common criticism of eugenics is that "it inevitably leads to measures that are unethical" (Lynn 2001). A hypothetical scenario posits that if one racial minority group is perceived on average less intelligent than the racial majority group, then it is more likely that the racial minority group will be submitted to a eugenics program rather than the least intelligent members of the whole population. In addition eugenics advocates, as humans, wouldn't support a system that could recognise them as inferior, possibly leading to a bias against people of other ethnicities, religions or other categorisations than they themselves are of.[citation needed] H. L. Kaye wrote of "the obvious truth that eugenics has been discredited by Hitler's crimes" (Kaye 1989). R. L. Hayman argued "the eugenics movement is an anachronism, its political implications exposed by the Holocaust" (Hayman 1990).

Steven Pinker has stated that it is "a conventional wisdom among left-leaning academics that genes imply genocide". He has responded to this "conventional wisdom" by comparing the history of Marxism, which had the opposite position on genes to that of Nazism:

But the 20th century suffered "two" ideologies that led to genocides. The other one, Marxism, had no use for race, didn't believe in genes and denied that human nature was a meaningful concept. Clearly, it's not an emphasis on genes or evolution that is dangerous. It's the desire to remake humanity by coercive means (eugenics or social engineering) and the belief that humanity advances through a struggle in which superior groups (race or classes) triumph over inferior ones.[39]

Genetic diversity

Eugenic policies could also lead to loss of genetic diversity, in which case a culturally accepted "improvement" of the gene pool could very likely, as evidenced in numerous instances in isolated island populations (e.g. the Dodo, Raphus cucullatus, of Mauritius) result in extinction due to increased vulnerability to disease, reduced ability to adapt to environmental change and other factors both known and unknown. A long-term species-wide eugenics plan might lead to a scenario similar to this because the elimination of traits deemed undesirable would reduce genetic diversity by definition. (Galton 2001, 48[citation needed]).

Proponents of eugenics argue that in any one generation any realistic program should make only minor changes in a fraction of the gene pool, giving plenty of time to reverse direction if unintended consequences emerge, reducing the likelihood of the elimination of desirable genes. Such people also argue that any appreciable reduction in diversity is so far in the future that little concern is needed for now.[40] The possible reduction of autism rates through selection against the genetic predisposition to autism is a significant political issue in the autism rights movement, which claims autism is a form of neurodiversity. Many advocates of Down syndrome rights also consider Down syndrome (Trisomy-21) a form of neurodiversity.[citation needed]

Heterozygous recessive traits

In some instances efforts to eradicate certain single-gene mutations would be nearly impossible. In the event the condition in question was a heterozygous recessive trait, the problem is that by eliminating the visible unwanted trait, there still may be many carriers for the genes without, or with fewer, phenotypic effects due to that gene. With genetic testing it may be possible to detect all of the heterozygous recessive traits. Under normal circumstances it is only possible to eliminate a dominant allele from the gene pool. Recessive traits can be severely reduced, but never eliminated unless the complete genetic makeup of all members of the pool was known, as aforementioned. As only very few undesirable traits, such as Huntington's disease, are dominant, one, from certain perspectives, may argue that the practicallity of "eliminating" traits is quite low.[citation needed]

There are examples of eugenic acts that managed to lower the prevalence of recessive diseases, although not influencing the prevalence of heterozygote carriers of those diseases. The elevated prevalence of certain genetically transmitted diseases among the Ashkenazi Jewish population (Tay–Sachs, cystic fibrosis, Canavan's disease and Gaucher's disease), has been decreased in current populations by the application of genetic screening.[41]

Supporters and critics

At its peak of popularity, eugenics was supported by a wide variety of prominent people, including Winston Churchill,[42] Margaret Sanger,[43][44] Marie Stopes, H. G. Wells, Norman Haire, Havelock Ellis, Theodore Roosevelt, George Bernard Shaw, John Maynard Keynes, John Harvey Kellogg, Linus Pauling[45] and Sidney Webb.[46][47][48] Its most infamous proponent and practitioner was, however, Adolf Hitler who praised and incorporated eugenic ideas in Mein Kampf and emulated Eugenic legislation for the sterilization of "defectives" that had been pioneered in the United States.[49]

The American sociologist Lester Frank Ward,[50] the English writer G. K. Chesterton and the German-American anthropologist Franz Boas [51] were all early critics of the philosophy of eugenics. Ward's 1913 article "Eugenics, Euthenics, and Eudemics", Chesterton's 1917 book Eugenics and Other Evils and Boas' 1916 article "Eugenics" (in Scientific Monthly magazine) were all harshly critical of the rapidly growing eugenics movement.

Among institutions, the Catholic Church was an early opponent of state-enforced eugenics.[52] In his 1930 encyclical Casti Connubii, Pope Pius XI explicitly condemned eugenics laws: "Public magistrates have no direct power over the bodies of their subjects; therefore, where no crime has taken place and there is no cause present for grave punishment, they can never directly harm, or tamper with the integrity of the body, either for the reasons of eugenics or for any other reason."[53]

In popular media

Galton and many others claimed that the less intelligent were more fertile than the more intelligent of his time. This is the basis of the movie Idiocracy, in which five hundred years in the future (2505) the dysgenic pressure has resulted in a uniformly stupid human society. The movie borrowed some of its plot from the 1951 science-fiction story The Marching Morons.

In Star Trek, there are conflicts known as the Eugenics Wars (or the Great Wars) which were a series of conflicts fought on Earth between 1993 and 1996. The result of a scientific attempt to improve the Human race through selective breeding and genetic engineering, the wars devastated parts of Earth, by some estimates officially causing some 30 million deaths, and nearly plunging the planet into a new Dark Age. (TOS: "Space Seed"; ENT: "Borderland")

In the movie Twins, a secret experiment was carried out at a genetics laboratory to produce the perfect human, using sperm donated by six different fathers. The experiment resulted in the birth of twins, named Julius and Vincent Benedict. While successful, the genetics program was considered a failure and shut down because one of the twins inherited the "desirable traits", while the other inherited the "genetic trash". The mother was told that her child died at birth, and the twins were raised separately from each other.

Also, in the movie Gattaca, a dystopian set of events is portrayed through the application of "artificial selection". This is then shown to be misused by employer and insurance companies and even schools, screening out the "in-valids". Through this, the protagonist, an "in-valid", is shown to go to great heights to reach his dreams of being an astronaut.

In the video game Grand Theft Auto IV, one of the many in-game advertisements is for "Eugenics Incorporated," a firm that purports to adjust the genetic makeup of a fetus to ensure that all characteristics are ideal.

In Frank Herbert's "Dune," the Bene Gesserit breeding program (Designed to produce the Kwisatz Haderach) is eugenics on a massive scale, calculating the exact genetic pairings needed to produce the Kwisatz Haderach over many generations. This was done without artificial insemination and, in some cases, without the knowledge of the participants. The result was Paul-Muad'dib, and his second son, Leto II.

-

Indiana Eugenics Law Marker in Indianapolis

-

Indiana Eugenics Law Marker in Indianapolis

See also

- Aktion T4

- Biological determinism

- Dysgenics

- Eugenics in the United States

- Sperm bank

- Ova bank

- Euthenics

- Genetic determinism

- Genism

- History of the race and intelligence controversy

- Race and genetics#Ancestral populations

- International Federation of Eugenics Organizations

- Kaiser Wilhelm Institute of Anthropology, Human Heredity, and Eugenics

- Liberal eugenics

- Life unworthy of life

- Oneida stirpiculture

- Racial hygiene

- Social Darwinism

- Culling

- Artificial selection

- Eugenics manifesto

Individuals:

- Karl Binding

- Alexis Carrel

- John Glad

- Hans Friedrich Karl Günther

- Alfred Hoche

- Lee Kuan Yew

- John M. MacEachran

- Bénédict Morel

- Alfred Ploetz

- Ernst Rüdin

- Margaret Sanger

- Katherine M. H. Blackford

- Georges Vacher de Lapouge

Organisations:

References

This article has an unclear citation style. (August 2009) |

- ^ Currell, Susan (2006). Popular Eugenics: National Efficiency and American Mass Culture in The 1930s. Athens, OH: Ohio University Press. p. 203. ISBN 0-8214-1691-X.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ "Eugenics", Unified Medical Language System (Psychological Index Terms) National Library of Medicine, 26 Sep. 2010.

- ^ Galton, Francis (1904). "Eugenics: Its Definition, Scope, and Aims". The American Journal of Sociology. X (1): 82, 1st paragraph. Bibcode:1904Natur..70...82. doi:10.1038/070082a0. Archived from the original on 2007-11-17. Retrieved 2010-12-27.

Eugenics is the science which deals with all influences that improve the inborn qualities of a race; also with those that develop them to the utmost advantage.

{{cite journal}}:|archive-date=/|archive-url=timestamp mismatch; 2007-11-03 suggested (help); Check|bibcode=length (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ The exact definition of eugenics has been a matter of debate since the term was coined. In the definition of it as a "social philosophy" — that is, a philosophy with implications for social order — is not meant to be definitive, and is taken from Osborn, Frederick (June 1937). "Development of a Eugenic Philosophy". American Sociological Review. 2 (3): 389–397. doi:10.2307/2084871.

- ^ http://www.amazon.com/DNA-The-Secret-Life-ebook/dp/B001PSEQAG

- ^ Blom 2008, p. 336

- ^ Ridley, Matt (1999). Genome: The Autobiography of a Species in 23 Chapters. New York: HarperCollins. pp. 290–1. ISBN 978-0-06-089408-5.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - ^ See for example, Black 2003

- ^ Allen, Garland E. (2004). "Was Nazi eugenics created in the US?". EMBO Rep. 5 (5): 451–2. doi:10.1038/sj.embor.7400158.

- ^ Barrett, Deborah; Kurzman, Charles (October 2004). "Globalizing Social Movement Theory: The Case of Eugenics". Theory and Society. 33 (5): 505.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "The National OFfice of Eugenics in Belgium" (PDF). Science. 57 (1463): 46. 12 January 1923. Bibcode:1923Sci....57R..46.. doi:10.1126/science.57.1463.46.

- ^ Sales Augusto dos Santos and Laurence Hallewell. Jan., 2002. Historical Roots of the "Whitening" of Brazil. Latin American Perspectives, Vol. 29, No. 1, Brazil: The Hegemonic Process in Political and Cultural Formation, pp. 81

- ^ McLaren, Angus (1990). Our Own Master Race: Eugenics in Canada, 1885–1945. Toronto: Oxford University Press.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - ^ a b "Social Democrats implemented measures to forcibly sterilise 62,000 people". World Socialist Web Site.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help); Invalid|ref=harv(help) - ^ Black 2003

- ^ Lynn, Richard (2001). Eugenics: a reassessment. New York: Praeger. p. 18. ISBN 0-275-95822-1.

By the middle decades of the twentieth century, eugenics had become widely accepted throughout the whole of the economically developed world, with the exception of the Soviet Union.

- ^ Schmuhl, Hans-Walter (2003). "The Kaiser Wilhelm Institute for Anthropology, Human Heredity and Eugenics, 1927–1945". Boston Studies in the Philosophy of Science. 259. Göttengen: Wallstein Verlag: 245.

- ^ See for example Weigmann K (2001). "In the name of science. The role of biologists in Nazi atrocities: lessons for today's scientists". EMBO Rep. 2 (10). European Molecular Biology Organization: 871–5. doi:10.1093/embo-reports/kve217. PMC 1084095. PMID 11600445.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) It concludes, "It was scientists who interpreted racial differences as the justification to murder ... It is the responsibility of today's scientists to prevent this from happening again." - ^ Article 2 of the Convention defines genocide as any of the following acts committed with intent to destroy, in whole or in part, a national, ethnic, racial or religious group, as such:

- (a) Killing members of the group;

- (b) Causing serious bodily or mental harm to members of the group;

- (c) Deliberately inflicting on the group conditions of life calculated to bring about its physical destruction in whole or in part;

- (d) Imposing measures intended to prevent births within the group;

- (e) Forcibly transferring children of the group to another group.

- ^ Charter of Fundamental Rights of the European Union, Article 3, 2

- ^ Galton, Francis (1883). Inquiries into Human Faculty and its Development. London: Macmillan Publishers. p. 199.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ "Correspondence between Francis Galton and Charles Darwin". Galton.org. Retrieved 2011-11-28.

- ^ "Darwin Correspondence Project » The correspondence of Charles Darwin, volume 17: 1869". Darwinproject.ac.uk. Retrieved 2011-11-28.

- ^ Blom, Philipp (2008). The Vertigo Years: Change and Culture in the West, 1900-1914. Toronto: McClelland & Stewart. pp. 335–6. ISBN 978-0-7710-1630-1.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - ^ Lester Frank Ward; Emily Palmer Cape; Sarah Emma Simons (1918). "Eugenics, Euthenics and Eudemics". Glimpses of the cosmos. G. P. Putnam's sons. pp. 382–. Retrieved 11 April 2012.

- ^ cited in Black 2003, p. 18

- ^ Haldane, J. (1940). "Lysenko and Genetics". Science and Society. 4 (4).

- ^ A discussion of the shifting meanings of the term can be found in Paul, Diane (1995). Controlling human heredity: 1865 to the present. New Jersey: Humanities Press. ISBN 1-57392-343-5.

- ^ Black, Edwin (2004). War Against the Weak. Thunder's Mouth Press. p. 370. ISBN isbn=978-1-56858-321-1.

{{cite book}}: Check|isbn=value: invalid character (help); Missing pipe in:|isbn=(help) - ^ a b http://journals1.scholarsportal.info.myaccess.library.utoronto.ca/tmp/15510468026065759357.pdf

- ^ a b Glad, 2008

- ^ Lisa Pine (1997). Nazi Family Policy, 1933–1945. Berg. pp. 19–. ISBN 978-1-85973-907-5. Retrieved 11 April 2012.

- ^ Rose, Nikolas (2007). The Politics of Life Itself: Biomedicine, Power, and Subjectivity in the Twenty-First Century. Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press. p. 372. ISBN 0-691-12191-5.

- ^ Attention: This template ({{cite doi}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by doi:10.1017/S0021932009003344, please use {{cite journal}} (if it was published in a bona fide academic journal, otherwise {{cite report}} with

|doi=10.1017/S0021932009003344instead. - ^ a b Attention: This template ({{cite doi}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by doi:10.1016/j.intell.2007.03.004, please use {{cite journal}} (if it was published in a bona fide academic journal, otherwise {{cite report}} with

|doi=10.1016/j.intell.2007.03.004instead. - ^ Van Court, Marian (1983). "Unwanted Births And Dysgenic Reproduction In The United States". Eugenics Bulletin.

- ^ Lynn, Richard (1996). Dysgenics: genetic deterioration in modern populations. Praeger. ISBN 978-0-275-94917-4.

- ^ a b Blom 2008, pp. 336–7

- ^ "United Press International: Q&A: Steven Pinker of 'Blank Slate". Retrieved 2006-08-26.

- ^ Miller, Edward M. (1997). "Eugenics: Economics for the Long Run". Research in Biopolitics. 5: 391–416.

- ^ Title: Fatal Gift: Jewish Intelligence and Western Civilization[dead link]

- ^ "Winston Churchill and Eugenics". Winstonchurchill.org. 2009-05-31. Retrieved 2011-11-28.

- ^ Margaret Sanger, quoted in Katz, Esther (2002). The Selected Papers of Margaret Sanger. Champaign, IL: University of Illinois Press. p. 319. ISBN 978-0-252-02737-6.

Our...campaign for Birth Control is not merely of eugenic value, but is practically identical in ideal with the final aims of Eugenics

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Franks, Angela (2005). Margaret Sanger's eugenic legacy. Jefferson, NC: McFarland. p. 30. ISBN 978-0-7864-2011-7.

...her commitment to eugenics was constant...until her death

- ^ Everett Mendelsohn, Ph.D. Pauling's Eugenics, The Eugenic Temptation, Harvard Magazine, March–April 2000

- ^ Gordon, Linda (2002). The Moral Property of Women: A History of Birth Control Politics in America. University of Illinois Press. p. 196. ISBN 0-252-02764-7.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ Keynes, John Maynard (1946). "Opening remarks: The Galton Lecture". The Eugenics Review. 38 (1): 39–40.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - ^ Okuefuna, David. "Racism: a history". British Broadcasting Corporation. Retrieved 2007-12-12.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ Black 2003, pp. 274–295

- ^ Ferrante, Joan (1 January 2010). Sociology: A Global Perspective. Cengage Learning. pp. 259–. ISBN 978-0-8400-3204-1.

- ^ Turda, Marius, "Race, Science and Eugenics in the Twentieth Century in Bashford, Alison, and Levine, Philippa The Oxford Handbook of the History of Eugenics Oxford University Press, 2010 ISBN 0199888299 (p. 72-73).

- ^ http://www.eugenicsarchive.org/eugenics/topics_fs.pl?theme=26

- ^ http://www.vatican.va/holy_father/pius_xi/encyclicals/documents/hf_p-xi_enc_31121930_casti-connubii_en.html

Sources

- Larson, Edward J. (2004). "Evolution". Modern Library. ISBN 0-679-64288-9.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help); Invalid|ref=harv(help)

- Histories of eugenics (academic accounts)

- Carlson, Elof Axel (2001). The Unfit: A History of a Bad Idea. Cold Spring Harbor NY: Cold Spring Harbor Press. ISBN 0-87969-587-0.

- Kevles, Daniel J. (1985). In the Name of Eugenics: Genetics and the Uses of Human Heredity. University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-05763-0.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Farrall, Lyndsay (1985), The origins and growth of the English eugenics movement, 1865-1925, Garland Pub, ISBN 978-0-8240-5810-4

- Dieter Kuntz, ed., Deadly medicine: creating the master race (Washington, DC: United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, 2004). online exhibit

- Largent, Mark (2008). Breeding Contempt: The History of Coerced Sterilization in the United States. New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press. ISBN 978-0-8135-4183-9.

- Engs, Ruth C. (2005). The Eugenics Movement: An Encyclopedia. Westport CT: Greenwood Publishing. ISBN 0-313-32791-2.

- Glad, John (2008). Future Human Evolution: Eugenics in the Twenty-First Century (PDF). Hermitage Publishers. ISBN 1-55779-154-6.

- Wyndham, Diana (2003). Eugenics in Australia : striving for national fitness. London: Galton Institute. ISBN 978-0-9504066-7-1.

- Histories of hereditarian thought

- Barkan, Elazar (1992). The retreat of scientific racism: changing concepts of race in Britain and the United States between the world wars. New York: Cambridge University Press.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Gould, Stephen Jay (1981). The mismeasure of man. New York: Norton. ISBN 0-393-01489-4.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Ewen & Ewen, Typecasting: On the Arts and Sciences of Human Inequality (New York, Seven Stories Press, 2006).

- Criticisms of eugenics, historical and modern

- Black, Edwin (2003). War Against the Weak: Eugenics and America's Campaign to Create a Master Race. Four Walls Eight Windows. ISBN 1-56858-258-7.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Dinesh D'Souza, The End of Racism (Free Press, 1995) ISBN 0-02-908102-5

- David Galton, Eugenics: The Future of Human Life in the 21st Century (Abacus, 2002) ISBN 0-349-11377-7

- Jonah Goldberg, Liberal Fascism: The Secret History of the American Left, from Mussolini to the Politics of Meaning (ISBN 0-385-51184-1)

- Hayman, Robert L. (1990). "Presumptions of justice: Law, politics, and the mentally retarded parent". Harvard Law Review. 103 (6): 1202–71. doi:10.2307/1341412. (p. 1209)

- Joseph, J. (2004). The Gene Illusion: Genetic Research in Psychiatry and Psychology Under the Microscope. New York: Algora. (2003 United Kingdom Edition by PCCS Books)

- —— (2005). The 1942 "Euthanasia" Debate in the American Journal of Psychiatry. History of Psychiatry, 16, 171–179.

- —— (2006). The Missing Gene: Psychiatry, Heredity, and the Fruitless Search for Genes. New York: Algora.

- H. L. Kaye, The social meaning of modern biology 1987, New Haven, CT Yale University Press. (p. 46)

- Maranto, Gina (1996). Quest for perfection : the drive to breed better human beings. New York: Scribner. ISBN 0-684-80029-2.

- Wahlsten, D. (1997). "Leilani Muir versus the Philosopher King: eugenics on trial in Alberta". Genetica. 99 (2–3): 185–198. doi:10.1007/BF02259522. PMID 9463073.

- Shakespeare, Tom (1995). "Back to the Future? New Genetics and Disabled People". Critical Social Policy. 46 (44–45): 22–35. doi:10.1177/026101839501504402.

- Tom Shakespeare, Genetic Politics: from Eugenics to Genome, with Anne Kerr (New Clarion Press, 2002).

- Nancy Ordover, American Eugenics: Race, Queer Anatomy, and the Science of Nationalism (Minneapolis: University of Minneapolis Press, 2003). ISBN 0-8166-3559-5

- Andrea Smith, Conquest: Sexual Violence and the American Indian Genocide (Cambridge, MA: South End Press, 2005).