Nuclear fusion

| Nuclear physics |

|---|

|

In nuclear physics, nuclear fusion is a nuclear reaction in which two or more atomic nuclei come close enough to form one or more different atomic nuclei and subatomic particles (neutrons and/or protons). The difference in mass between the products and reactants is manifested as the release of large amounts of energy. This difference in mass arises due to the difference in atomic "binding energy" between the atomic nuclei before and after the reaction. Fusion is the process that powers active or "main sequence" stars, or other high magnitude stars.

The fusion process that produces a nucleus lighter than iron-56 or nickel-62 will generally yield a net energy release. These elements have the smallest mass per nucleon and the largest binding energy per nucleon, respectively. Fusion of light elements toward these releases energy (an exothermic process), while a fusion producing nuclei heavier than these elements, will result in energy retained by the resulting nucleons, and the resulting reaction is endothermic. The opposite is true for the reverse process, nuclear fission. This means that the lighter elements, such as hydrogen and helium, are in general more fusible; while the heavier elements, such as uranium and plutonium, are more fissionable. The extreme astrophysical event of a supernova can produce enough energy to fuse nuclei into elements heavier than iron.

Following the discovery of quantum tunneling by physicist Friedrich Hund, in 1929 Robert Atkinson and Fritz Houtermans used the measured masses of light elements to predict that large amounts of energy could be released by fusing small nuclei. Building upon the nuclear transmutation experiments by Ernest Rutherford, carried out several years earlier, the laboratory fusion of hydrogen isotopes was first accomplished by Mark Oliphant in 1932. During the remainder of that decade the steps of the main cycle of nuclear fusion in stars were worked out by Hans Bethe. Research into fusion for military purposes began in the early 1940s as part of the Manhattan Project. Fusion was accomplished in 1951 with the Greenhouse Item nuclear test. Nuclear fusion on a large scale in an explosion was first carried out on November 1, 1952, in the Ivy Mike hydrogen bomb test.

Research into developing controlled thermonuclear fusion for civil purposes also began in earnest in the 1950s, and it continues to this day. An unknown amount of money and time has been spent pursuing what many scientists believe is an impossible goal. To date controlled fusion has only consisted of "bursts" lasting fractions of a second. Despite the complete and total lack of success creating controlled, sustained fusion, vast sums of money are being spent planning, designing and marketing nuclear fusion powerplants.

Process

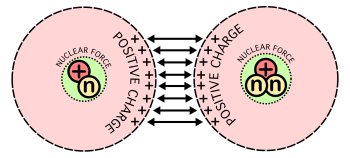

The origin of the energy released in fusion of light elements is due to interplay of two opposing forces, the nuclear force which combines together protons and neutrons, and the Coulomb force, which causes protons to repel each other. The protons are positively charged and repel each other but they nonetheless stick together, demonstrating the existence of another force referred to as nuclear attraction. This force, called the strong nuclear force, overcomes electric repulsion at very close range. The effect of this force is not observed outside the nucleus, hence the force is called a short-range force. The same force also pulls the nucleons (neutrons and protons) together allowing ordinary matter to exist.[2] Light nuclei (or nuclei smaller than iron and nickel), are sufficiently small and proton-poor allowing the nuclear force to overcome the repulsive Coulomb force. This is because the nucleus is sufficiently small that all nucleons feel the short-range attractive force at least as strongly as they feel the infinite-range Coulomb repulsion. Building up these nuclei from lighter nuclei by fusion thus releases the extra energy from the net attraction of these particles. For larger nuclei, however, no energy is released, since the nuclear force is short-range and cannot continue to act across still larger atomic nuclei. Thus, energy is no longer released when such nuclei are made by fusion; instead, energy is required as input to such processes.

Fusion reactions create the light elements that power the stars and produce virtually all elements in a process called nucleosynthesis. The fusion of lighter elements in stars releases energy and the mass that always accompanies it. For example, in the fusion of two hydrogen nuclei to form helium, 0.7% of the mass is carried away from the system in the form of kinetic energy of an alpha particle or other forms of energy, such as electromagnetic radiation.[3]

Research into controlled fusion, with the aim of producing fusion power for the production of electricity, has been conducted for over 60 years. It has been accompanied by extreme scientific and technological difficulties, but has resulted in progress. At present, controlled fusion reactions have been unable to produce break-even (self-sustaining) controlled fusion.[4] Workable designs for a reactor that theoretically will deliver ten times more fusion energy than the amount needed to heat plasma to the required temperatures are in development (see ITER). The ITER facility is expected to finish its construction phase in 2019. It will start commissioning the reactor that same year and initiate plasma experiments in 2020, but is not expected to begin full deuterium-tritium fusion until 2027.[5]

It takes considerable energy to force nuclei to fuse, even those of the lightest element, hydrogen. This is because all nuclei have a positive charge due to their protons, and as like charges repel, nuclei strongly resist being pushed close together. When accelerated to high enough speeds, nuclei can overcome this electrostatic repulsion and brought close enough such that the attractive nuclear force is greater than the repulsive Coulomb force. As the strong force grows very rapidly once beyond that critical distance, the fusing nucleons "fall" into one another and result is fusion and net energy produced. The fusion of lighter nuclei, which creates a heavier nucleus and often a free neutron or proton, generally releases more energy than it takes to force the nuclei together; this is an exothermic process that can produce self-sustaining reactions. The US National Ignition Facility, which uses laser-driven inertial confinement fusion, was designed with a goal of break-even fusion.

The first large-scale laser target experiments were performed in June 2009 and ignition experiments began in early 2011.[6][7]

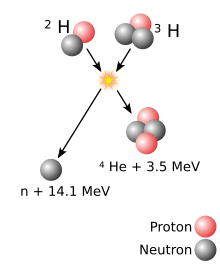

Energy released in most nuclear reactions are much larger than in chemical reactions, because the binding energy that holds a nucleus together is far greater than the energy that holds electrons to a nucleus. For example, the ionization energy gained by adding an electron to a hydrogen nucleus is 13.6 eV—less than one-millionth of the 17.6 MeV released in the deuterium–tritium (D–T) reaction shown in the adjacent diagram. The complete conversion of one gram of matter would release 9×1013 joules of energy. Fusion reactions have an energy density many times greater than nuclear fission; the reactions produce far greater energy per unit of mass even though individual fission reactions are generally much more energetic than individual fusion ones, which are themselves millions of times more energetic than chemical reactions. Only direct conversion of mass into energy, such as that caused by the annihilatory collision of matter and antimatter, is more energetic per unit of mass than nuclear fusion.

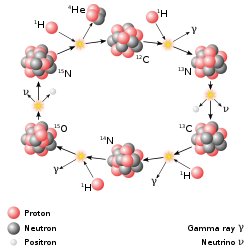

Nuclear fusion in stars

The most important fusion process in nature is the one that powers stars, stellar nucleosynthesis. In the 20th century, it was realized that the energy released from nuclear fusion reactions accounted for the longevity of the Sun and other stars as a source of heat and light. The fusion of nuclei in a star, starting from its initial hydrogen and helium abundance, provides that energy and synthesizes new nuclei as a byproduct of the fusion process. The prime energy producer in the Sun is the fusion of hydrogen to form helium, which occurs at a solar-core temperature of 14 million kelvin. The net result is the fusion of four protons into one alpha particle, with the release of two positrons, two neutrinos (which changes two of the protons into neutrons), and energy. Different reaction chains are involved, depending on the mass of the star. For stars the size of the sun or smaller, the proton-proton chain dominates. In heavier stars, the CNO cycle is more important.

As a star uses up a substantial fraction of its hydrogen, it begins to synthesize heavier elements. However the heaviest elements are synthesized by fusion that occurs as a more massive star undergoes a violent supernova at the end of its life, a process known as supernova nucleosynthesis.

Requirements

Details and supporting references on the material in this section can be found in textbooks on nuclear physics or nuclear fusion.[8]

A substantial energy barrier of electrostatic forces must be overcome before fusion can occur. At large distances, two naked nuclei repel one another because of the repulsive electrostatic force between their positively charged protons. If two nuclei can be brought close enough together, however, the electrostatic repulsion can be overcome by the quantum effect in which nuclei can tunnel through columb forces.

When a nucleon such as a proton or neutron is added to a nucleus, the nuclear force attracts it to all the other nucleons of the nucleus (if the atom is small enough), but primarily to its immediate neighbours due to the short range of the force. The nucleons in the interior of a nucleus have more neighboring nucleons than those on the surface. Since smaller nuclei have a larger surface area-to-volume ratio, the binding energy per nucleon due to the nuclear force generally increases with the size of the nucleus but approaches a limiting value corresponding to that of a nucleus with a diameter of about four nucleons. It is important to keep in mind that nucleons are quantum objects. So, for example, since two neutrons in a nucleus are identical to each other, the goal of distinguishing one from the other, such as which one is in the interior and which is on the surface, is in fact meaningless, and the inclusion of quantum mechanics is therefore necessary for proper calculations.

The electrostatic force, on the other hand, is an inverse-square force, so a proton added to a nucleus will feel an electrostatic repulsion from all the other protons in the nucleus. The electrostatic energy per nucleon due to the electrostatic force thus increases without limit as nuclei atomic number grows.

The net result of the opposing electrostatic and strong nuclear forces is that the binding energy per nucleon generally increases with increasing size, up to the elements iron and nickel, and then decreases for heavier nuclei. Eventually, the binding energy becomes negative and very heavy nuclei (all with more than 208 nucleons, corresponding to a diameter of about 6 nucleons) are not stable. The four most tightly bound nuclei, in decreasing order of binding energy per nucleon, are 62

Ni

, 58

Fe

, 56

Fe

, and 60

Ni

.[9] Even though the nickel isotope, 62

Ni

, is more stable, the iron isotope 56

Fe

is an order of magnitude more common. This is due to the fact that there is no easy way for stars to create 62

Ni

through the alpha process.

An exception to this general trend is the helium-4 nucleus, whose binding energy is higher than that of lithium, the next heaviest element. This is because protons and neutrons are fermions, which according to the Pauli exclusion principle cannot exist in the same nucleus in exactly the same state. Each proton or neutron energy state in a nucleus can accommodate both a spin up particle and a spin down particle. Helium-4 has an anomalously large binding energy because its nucleus consists of two protons and two neutrons, so all four of its nucleons can be in the ground state. Any additional nucleons would have to go into higher energy states. Indeed, the helium-4 nucleus is so tightly bound that it is commonly treated as a single particle in nuclear physics, namely, the alpha particle.

The situation is similar if two nuclei are brought together. As they approach each other, all the protons in one nucleus repel all the protons in the other. Not until the two nuclei actually come close enough for long enough can the strong nuclear force take over (by way of tunneling). Consequently, even when the final energy state is lower, there is a large energy barrier that must first be overcome. It is called the Coulomb barrier.

The Coulomb barrier is smallest for isotopes of hydrogen, as their nuclei contain only a single positive charge. A diproton is not stable, so neutrons must also be involved, ideally in such a way that a helium nucleus, with its extremely tight binding, is one of the products.

Using deuterium-tritium fuel, the resulting energy barrier is about 0.1 MeV. In comparison, the energy needed to remove an electron from hydrogen is 13.6 eV, about 7500 times less energy. The (intermediate) result of the fusion is an unstable 5He nucleus, which immediately ejects a neutron with 14.1 MeV. The recoil energy of the remaining 4He nucleus is 3.5 MeV, so the total energy liberated is 17.6 MeV. This is many times more than what was needed to overcome the energy barrier.

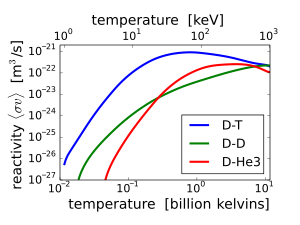

The reaction cross section σ is a measure of the probability of a fusion reaction as a function of the relative velocity of the two reactant nuclei. If the reactants have a distribution of velocities, e.g. a thermal distribution, then it is useful to perform an average over the distributions of the product of cross section and velocity. This average is called the 'reactivity', denoted <σv>. The reaction rate (fusions per volume per time) is <σv> times the product of the reactant number densities:

If a species of nuclei is reacting with itself, such as the DD reaction, then the product must be replaced by .

increases from virtually zero at room temperatures up to meaningful magnitudes at temperatures of 10–100 keV. At these temperatures, well above typical ionization energies (13.6 eV in the hydrogen case), the fusion reactants exist in a plasma state.

The significance of as a function of temperature in a device with a particular energy confinement time is found by considering the Lawson criterion. This is an extremely challenging barrier to overcome on Earth, which explains why fusion research has taken many years to reach the current high state of technical prowess.[10]

Methods for achieving fusion

Thermonuclear fusion

If the matter is sufficiently heated (hence being plasma), the fusion reaction may occur due to collisions with extreme thermal kinetic energies of the particles. In the form of thermonuclear weapons, thermonuclear fusion is the only fusion technique so far to yield undeniably large amounts of useful fusion energy. Usable amounts of thermonuclear fusion energy released in a controlled manner have yet to be achieved. In nature, this is what produces energy in stars through stellar nucleosynthesis.

Inertial confinement fusion

Inertial confinement fusion (ICF) is a type of fusion energy research that attempts to initiate nuclear fusion reactions by heating and compressing a fuel target, typically in the form of a pellet that most often contains a mixture of deuterium and tritium.

Inertial electrostatic confinement

Inertial electrostatic confinement is a set of devices that use an electric field to heat ions to fusion conditions. The most well known is the fusor. Starting in 1999, a number of amateurs have been able to do amateur fusion using these homemade devices.[11][12][13][14][15] Other IEC devices include: the Polywell, MIX POPS[16] and Marble concepts.[17]

Beam-beam or beam-target fusion

If the energy to initiate the reaction comes from accelerating one of the nuclei, the process is called beam-target fusion; if both nuclei are accelerated, it is beam-beam fusion.

Accelerator-based light-ion fusion is a technique using particle accelerators to achieve particle kinetic energies sufficient to induce light-ion fusion reactions. Accelerating light ions is relatively easy, and can be done in an efficient manner—requiring only a vacuum tube, a pair of electrodes, and a high-voltage transformer; fusion can be observed with as little as 10 kV between the electrodes. The key problem with accelerator-based fusion (and with cold targets in general) is that fusion cross sections are many orders of magnitude lower than Coulomb interaction cross sections. Therefore, the vast majority of ions expend their energy emitting bremsstrahlung radiation and the ionization of atoms of the target. Devices referred to as sealed-tube neutron generators are particularly relevant to this discussion. These small devices are miniature particle accelerators filled with deuterium and tritium gas in an arrangement that allows ions of those nuclei to be accelerated against hydride targets, also containing deuterium and tritium, where fusion takes place, releasing a flux of neutrons. Hundreds of neutron generators are produced annually for use in the petroleum industry where they are used in measurement equipment for locating and mapping oil reserves.

Muon-catalyzed fusion

Muon-catalyzed fusion is a well-established and reproducible fusion process that occurs at ordinary temperatures. It was studied in detail by Steven Jones in the early 1980s. Net energy production from this reaction cannot occur because of the high energy required to create muons, their short 2.2 µs half-life, and the high chance that a muon will bind to the new alpha particle and thus stop catalyzing fusion.[18]

Other principles

Some other confinement principles have been investigated.

Antimatter-initialized fusion uses small amounts of antimatter to trigger a tiny fusion explosion. This has been studied primarily in the context of making nuclear pulse propulsion, and pure fusion bombs feasible. This is not near becoming a practical power source, due to the cost of manufacturing antimatter alone.

Pyroelectric fusion was reported in April 2005 by a team at UCLA. The scientists used a pyroelectric crystal heated from −34 to 7 °C (−29 to 45 °F), combined with a tungsten needle to produce an electric field of about 25 gigavolts per meter to ionize and accelerate deuterium nuclei into an erbium deuteride target. At the estimated energy levels,[19] the D-D fusion reaction may occur, producing helium-3 and a 2.45 MeV neutron. Although it makes a useful neutron generator, the apparatus is not intended for power generation since it requires far more energy than it produces.[20][21][22][23]

Hybrid nuclear fusion-fission (hybrid nuclear power) is a proposed means of generating power by use of a combination of nuclear fusion and fission processes. The concept dates to the 1950s, and was briefly advocated by Hans Bethe during the 1970s, but largely remained unexplored until a revival of interest in 2009, due to the delays in the realization of pure fusion.[24] Project PACER, carried out at Los Alamos National Laboratory (LANL) in the mid-1970s, explored the possibility of a fusion power system that would involve exploding small hydrogen bombs (fusion bombs) inside an underground cavity. As an energy source, the system is the only fusion power system that could be demonstrated to work using existing technology. However it would also require a large, continuous supply of nuclear bombs, making the economics of such a system rather questionable.

Important reactions

Astrophysical reaction chains

At the temperatures and densities in stellar cores the rates of fusion reactions are notoriously slow. For example, at solar core temperature (T ≈ 15 MK) and density (160 g/cm3), the energy release rate is only 276 μW/cm3—about a quarter of the volumetric rate at which a resting human body generates heat.[25] Thus, reproduction of stellar core conditions in a lab for nuclear fusion power production is completely impractical. Because nuclear reaction rates depend on density as well as temperature and most fusion scemes operate at relatively low densities, those methods are strongly dependent on higher temperatures. The fusion rate as a function of temperature (exp(−E/kT)), leads to the need to achieve temperatures in terrestrial reactors 10–100 times higher temperatures and in stellar interiors: T ≈ 0.1–1.0×109 K.

Criteria and candidates for terrestrial reactions

In artificial fusion, the primary fuel is not constrained to be protons and higher temperatures can be used, so reactions with larger cross-sections are chosen. Another concern is the production of neutrons, which activate the reactor structure radiologically, but also have the advantages of allowing volumetric extraction of the fusion energy and tritium breeding. Reactions that release no neutrons are referred to as aneutronic.

To be a useful energy source, a fusion reaction must satisfy several criteria. It must:

- Be exothermic

- This limits the reactants to the low Z (number of protons) side of the curve of binding energy. It also makes helium 4

He

the most common product because of its extraordinarily tight binding, although 3

He

and 3

H

also show up. - Involve low atomic number (Z) nuclei

- This is because the electrostatic repulsion must be overcome before the nuclei are close enough to fuse.[citation needed]

- Have two reactants

- At anything less than stellar densities, three body collisions are too improbable. In inertial confinement, both stellar densities and temperatures are exceeded to compensate for the shortcomings of the third parameter of the Lawson criterion, ICF's very short confinement time.

- Have two or more products

- This allows simultaneous conservation of energy and momentum without relying on the electromagnetic force.

- Conserve both protons and neutrons

- The cross sections for the weak interaction are too small.

Few reactions meet these criteria. The following are those with the largest cross sections:[26]

(1) 2

1D

+ 3

1T

→ 4

2He

( 3.5 MeV ) + n0 ( 14.1 MeV ) (2i) 2

1D

+ 2

1D

→ 3

1T

( 1.01 MeV ) + p+ ( 3.02 MeV ) 50% (2ii) → 3

2He

( 0.82 MeV ) + n0 ( 2.45 MeV ) 50% (3) 2

1D

+ 3

2He

→ 4

2He

( 3.6 MeV ) + p+ ( 14.7 MeV ) (4) 3

1T

+ 3

1T

→ 4

2He

+ 2 n0 + 11.3 MeV (5) 3

2He

+ 3

2He

→ 4

2He

+ 2 p+ + 12.9 MeV (6i) 3

2He

+ 3

1T

→ 4

2He

+ p+ + n0 + 12.1 MeV 57% (6ii) → 4

2He

( 4.8 MeV ) + 2

1D

( 9.5 MeV ) 43% (7i) 2

1D

+ 6

3Li

→ 2 4

2He

+ 22.4 MeV (7ii) → 3

2He

+ 4

2He

+ n0 + 2.56 MeV (7iii) → 7

3Li

+ p+ + 5.0 MeV (7iv) → 7

4Be

+ n0 + 3.4 MeV (8) p+ + 6

3Li

→ 4

2He

( 1.7 MeV ) + 3

2He

( 2.3 MeV ) (9) 3

2He

+ 6

3Li

→ 2 4

2He

+ p+ + 16.9 MeV (10) p+ + 11

5B

→ 3 4

2He

+ 8.7 MeV

| Nucleosynthesis |

|---|

|

| Related topics |

For reactions with two products, the energy is divided between them in inverse proportion to their masses, as shown. In most reactions with three products, the distribution of energy varies. For reactions that can result in more than one set of products, the branching ratios are given.

Some reaction candidates can be eliminated at once. The D-6Li reaction has no advantage compared to p+-11

5B

because it is roughly as difficult to burn but produces substantially more neutrons through 2

1D

-2

1D

side reactions. There is also a p+-7

3Li

reaction, but the cross section is far too low, except possibly when Ti > 1 MeV, but at such high temperatures an endothermic, direct neutron-producing reaction also becomes very significant. Finally there is also a p+-9

4Be

reaction, which is not only difficult to burn, but 9

4Be

can be easily induced to split into two alpha particles and a neutron.

In addition to the fusion reactions, the following reactions with neutrons are important in order to "breed" tritium in "dry" fusion bombs and some proposed fusion reactors:

The latter of the two equations was unknown when the U.S. conducted the Castle Bravo fusion bomb test in 1954. Being just the second fusion bomb ever tested (and the first to use lithium), the designers of the Castle Bravo "Shrimp" had understood the usefulness of Lithium-6 in tritium production, but had failed to recognize that Lithium-7 fission would greatly increase the yield of the bomb. While Li-7 has a small neutron cross-section for low neutron energies, it has a higher cross section above 5 MeV.[27] The 15 Mt yield was 150% greater than the predicted 6 Mt and caused unexpected exposure to fallout.

To evaluate the usefulness of these reactions, in addition to the reactants, the products, and the energy released, one needs to know something about the cross section. Any given fusion device has a maximum plasma pressure it can sustain, and an economical device would always operate near this maximum. Given this pressure, the largest fusion output is obtained when the temperature is chosen so that <σv>/T2 is a maximum. This is also the temperature at which the value of the triple product nTτ required for ignition is a minimum, since that required value is inversely proportional to <σv>/T2 (see Lawson criterion). (A plasma is "ignited" if the fusion reactions produce enough power to maintain the temperature without external heating.) This optimum temperature and the value of <σv>/T2 at that temperature is given for a few of these reactions in the following table.

| fuel | T [keV] | <σv>/T2 [m3/s/keV2] |

|---|---|---|

| 2 1D -3 1T |

13.6 | 1.24×10−24 |

| 2 1D -2 1D |

15 | 1.28×10−26 |

| 2 1D -3 2He |

58 | 2.24×10−26 |

| p+-6 3Li |

66 | 1.46×10−27 |

| p+-11 5B |

123 | 3.01×10−27 |

Note that many of the reactions form chains. For instance, a reactor fueled with 3

1T

and 3

2He

creates some 2

1D

, which is then possible to use in the 2

1D

-3

2He

reaction if the energies are "right". An elegant idea is to combine the reactions (8) and (9). The 3

2He

from reaction (8) can react with 6

3Li

in reaction (9) before completely thermalizing. This produces an energetic proton, which in turn undergoes reaction (8) before thermalizing. Detailed analysis shows that this idea would not work well,[citation needed] but it is a good example of a case where the usual assumption of a Maxwellian plasma is not appropriate.

Neutronicity, confinement requirement, and power density

Any of the reactions above can in principle be the basis of fusion power production. In addition to the temperature and cross section discussed above, we must consider the total energy of the fusion products Efus, the energy of the charged fusion products Ech, and the atomic number Z of the non-hydrogenic reactant.

Specification of the 2

1D

-2

1D

reaction entails some difficulties, though. To begin with, one must average over the two branches (2i) and (2ii). More difficult is to decide how to treat the 3

1T

and 3

2He

products. 3

1T

burns so well in a deuterium plasma that it is almost impossible to extract from the plasma. The 2

1D

-3

2He

reaction is optimized at a much higher temperature, so the burnup at the optimum 2

1D

-2

1D

temperature may be low, so it seems reasonable to assume the 3

1T

but not the 3

2He

gets burned up and adds its energy to the net reaction. Thus the total reaction would be the sum of (2i), (2ii), and (1):

We count the 2

1D

-2

1D

fusion energy per D-D reaction (not per pair of deuterium atoms) as Efus = (4.03 MeV + 17.6 MeV)×50% + (3.27 MeV)×50% = 12.5 MeV and the energy in charged particles as Ech = (4.03 MeV + 3.5 MeV)×50% + (0.82 MeV)×50% = 4.2 MeV. (Note: if the tritium ion reacts with a deuteron while it still has a large kinetic energy, then the kinetic energy of the helium-4 produced may be quite different from 3.5 MeV, so this calculation of energy in charged particles is only approximate.)

Another unique aspect of the 2

1D

-2

1D

reaction is that there is only one reactant, which must be taken into account when calculating the reaction rate.

With this choice, we tabulate parameters for four of the most important reactions

| fuel | Z | Efus [MeV] | Ech [MeV] | neutronicity |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2 1D -3 1T |

1 | 17.6 | 3.5 | 0.80 |

| 2 1D -2 1D |

1 | 12.5 | 4.2 | 0.66 |

| 2 1D -3 2He |

2 | 18.3 | 18.3 | ~0.05 |

| p+-11 5B |

5 | 8.7 | 8.7 | ~0.001 |

The last column is the neutronicity of the reaction, the fraction of the fusion energy released as neutrons. This is an important indicator of the magnitude of the problems associated with neutrons like radiation damage, biological shielding, remote handling, and safety. For the first two reactions it is calculated as (Efus-Ech)/Efus. For the last two reactions, where this calculation would give zero, the values quoted are rough estimates based on side reactions that produce neutrons in a plasma in thermal equilibrium.

Of course, the reactants should also be mixed in the optimal proportions. This is the case when each reactant ion plus its associated electrons accounts for half the pressure. Assuming that the total pressure is fixed, this means that density of the non-hydrogenic ion is smaller than that of the hydrogenic ion by a factor 2/(Z+1). Therefore, the rate for these reactions is reduced by the same factor, on top of any differences in the values of <σv>/T2. On the other hand, because the 2

1D

-2

1D

reaction has only one reactant, its rate is twice as high as when the fuel is divided between two different hydrogenic species, thus creating a more efficient reaction.

Thus there is a "penalty" of (2/(Z+1)) for non-hydrogenic fuels arising from the fact that they require more electrons, which take up pressure without participating in the fusion reaction. (It is usually a good assumption that the electron temperature will be nearly equal to the ion temperature. Some authors, however discuss the possibility that the electrons could be maintained substantially colder than the ions. In such a case, known as a "hot ion mode", the "penalty" would not apply.) There is at the same time a "bonus" of a factor 2 for 2

1D

-2

1D

because each ion can react with any of the other ions, not just a fraction of them.

We can now compare these reactions in the following table.

| fuel | <σv>/T2 | penalty/bonus | reactivity | Lawson criterion | power density (W/m3/kPa2) | relation of power density |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2 1D -3 1T |

1.24×10−24 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 34 | 1 |

| 2 1D -2 1D |

1.28×10−26 | 2 | 48 | 30 | 0.5 | 68 |

| 2 1D -3 2He |

2.24×10−26 | 2/3 | 83 | 16 | 0.43 | 80 |

| p+-6 3Li |

1.46×10−27 | 1/2 | 1700 | 0.005 | 6800 | |

| p+-11 5B |

3.01×10−27 | 1/3 | 1240 | 500 | 0.014 | 2500 |

The maximum value of <σv>/T2 is taken from a previous table. The "penalty/bonus" factor is that related to a non-hydrogenic reactant or a single-species reaction. The values in the column "reactivity" are found by dividing 1.24×10−24 by the product of the second and third columns. It indicates the factor by which the other reactions occur more slowly than the 2

1D

-3

1T

reaction under comparable conditions. The column "Lawson criterion" weights these results with Ech and gives an indication of how much more difficult it is to achieve ignition with these reactions, relative to the difficulty for the 2

1D

-3

1T

reaction. The last column is labeled "power density" and weights the practical reactivity with Efus. It indicates how much lower the fusion power density of the other reactions is compared to the 2

1D

-3

1T

reaction and can be considered a measure of the economic potential.

Bremsstrahlung losses in quasineutral, isotropic plasmas

The ions undergoing fusion in many systems will essentially never occur alone but will be mixed with electrons that in aggregate neutralize the ions' bulk electrical charge and form a plasma. The electrons will generally have a temperature comparable to or greater than that of the ions, so they will collide with the ions and emit x-ray radiation of 10–30 keV energy, a process known as Bremsstrahlung.

The huge size of the Sun and stars means that the x-rays produced in this process will not escape and will deposit their energy back into the plasma. They are said to be opaque to x-rays. But any terrestrial fusion reactor will be optically thin for x-rays of this energy range. X-rays are difficult to reflect but they are effectively absorbed (and converted into heat) in less than mm thickness of stainless steel (which is part of a reactor's shield). This means the bremsstrahlung process is carrying energy out of the plasma, cooling it.

The ratio of fusion power produced to x-ray radiation lost to walls is an important figure of merit. This ratio is generally maximized at a much higher temperature than that which maximizes the power density (see the previous subsection). The following table shows estimates of the optimum temperature and the power ratio at that temperature for several reactions.

| fuel | Ti (keV) | Pfusion/PBremsstrahlung |

|---|---|---|

| 2 1D -3 1T |

50 | 140 |

| 2 1D -2 1D |

500 | 2.9 |

| 2 1D -3 2He |

100 | 5.3 |

| 3 2He -3 2He |

1000 | 0.72 |

| p+-6 3Li |

800 | 0.21 |

| p+-11 5B |

300 | 0.57 |

The actual ratios of fusion to Bremsstrahlung power will likely be significantly lower for several reasons. For one, the calculation assumes that the energy of the fusion products is transmitted completely to the fuel ions, which then lose energy to the electrons by collisions, which in turn lose energy by Bremsstrahlung. However, because the fusion products move much faster than the fuel ions, they will give up a significant fraction of their energy directly to the electrons. Secondly, the ions in the plasma are assumed to be purely fuel ions. In practice, there will be a significant proportion of impurity ions, which will then lower the ratio. In particular, the fusion products themselves must remain in the plasma until they have given up their energy, and will remain some time after that in any proposed confinement scheme. Finally, all channels of energy loss other than Bremsstrahlung have been neglected. The last two factors are related. On theoretical and experimental grounds, particle and energy confinement seem to be closely related. In a confinement scheme that does a good job of retaining energy, fusion products will build up. If the fusion products are efficiently ejected, then energy confinement will be poor, too.

The temperatures maximizing the fusion power compared to the Bremsstrahlung are in every case higher than the temperature that maximizes the power density and minimizes the required value of the fusion triple product. This will not change the optimum operating point for 2

1D

-3

1T

very much because the Bremsstrahlung fraction is low, but it will push the other fuels into regimes where the power density relative to 2

1D

-3

1T

is even lower and the required confinement even more difficult to achieve. For 2

1D

-2

1D

and 2

1D

-3

2He

, Bremsstrahlung losses will be a serious, possibly prohibitive problem. For 3

2He

-3

2He

, p+-6

3Li

and p+-11

5B

the Bremsstrahlung losses appear to make a fusion reactor using these fuels with a quasineutral, isotropic plasma impossible. Some ways out of this dilemma are considered—and rejected—in fundamental limitations on plasma fusion systems not in thermodynamic equilibrium.[28][29] This limitation does not apply to non-neutral and anisotropic plasmas; however, these have their own challenges to contend with.

See also

References

- ^

Shultis, J.K.; Faw, R.E. (2002). Fundamentals of nuclear science and engineering. CRC Press. p. 151. ISBN 0-8247-0834-2.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|lastauthoramp=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help) - ^ Physics Flexbook. Ck12.org. Retrieved on 2012-12-19.

- ^ Bethe, Hans A. "The Hydrogen Bomb", Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, April 1950, p. 99.

- ^ "Progress in Fusion". ITER. Retrieved 15 February 2010.

- ^ "ITER – the way to new energy". ITER. 2014.

- ^ Moses, E. I. (2009). "The National Ignition Facility: Ushering in a new age for high energy density science". Phys. Plasmas. 16: 041006. doi:10.1063/1.3116505.

- ^ Kramer, David (March 2011). "DOE looks again at inertial fusion as potential clean-energy source". Physics Today. 64 (3): 26. doi:10.1063/1.3563814.

- ^ Atzeni, S. and Meyer-ter-Vehn, J. (2004). Chapter 1: "Nuclear fusion reactions" in The Physics of Inertial Fusion. University of Oxford Press. ISBN 978-0-19-856264-1

- ^ The Most Tightly Bound Nuclei. Hyperphysics.phy-astr.gsu.edu. Retrieved on 2011-08-17.

- ^ What Is The Lawson Criteria, Or How to Make Fusion Power Viable

- ^ "Fusor Forums • Index page". Fusor.net. Retrieved 24 August 2014.

- ^ "Build a Nuclear Fusion Reactor? No Problem". Clhsonline.net. 23 March 2012. Retrieved 24 August 2014.

- ^ "Extreme DIY: Building a homemade nuclear reactor in NYC". BBC News. Retrieved 30 October 2014.

- ^ Schechner, Sam (18 August 2008). "Nuclear Ambitions: Amateur Scientists Get a Reaction From Fusion – WSJ". Online.wsj.com. Retrieved 24 August 2014.

- ^ "Will's Amateur Science and Engineering: Fusion Reactor's First Light!". Tidbit77.blogspot.com. 9 February 2010. Retrieved 24 August 2014.

- ^ Park J, Nebel RA, Stange S, Murali SK (2005). "Experimental Observation of a Periodically Oscillating Plasma Sphere in a Gridded Inertial Electrostatic Confinement Device". Phys Rev Lett. 95 (1): 015003. Bibcode:2005PhRvL..95a5003P. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.95.015003. PMID 16090625.

- ^ "The Multiple Ambipolar Recirculating Beam Line Experiment" Poster presentation, 2011 US-Japan IEC conference, Dr. Alex Klein

- ^ Jones, S.E. (1986). "Muon-Catalysed Fusion Revisited". Nature. 321 (6066): 127–133. Bibcode:1986Natur.321..127J. doi:10.1038/321127a0.

- ^ Supplementary methods for "Observation of nuclear fusion driven by a pyroelectric crystal". Main article Naranjo, B.; Gimzewski, J.K.; Putterman, S. (2005). "Observation of nuclear fusion driven by a pyroelectric crystal". Nature. 434 (7037): 1115–1117. Bibcode:2005Natur.434.1115N. doi:10.1038/nature03575. PMID 15858570.

- ^ UCLA Crystal Fusion. Rodan.physics.ucla.edu. Retrieved on 2011-08-17. Archived 8 June 2015 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Schewe, Phil; Stein, Ben (2005). "Pyrofusion: A Room-Temperature, Palm-Sized Nuclear Fusion Device". Physics News Update. 729 (1). Archived from the original on 12 November 2013.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|lastauthoramp=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help) - ^ Coming in out of the cold: nuclear fusion, for real. Christiansciencemonitor.com (2005-06-06). Retrieved on 2011-08-17.

- ^ Nuclear fusion on the desktop ... really!. MSNBC (2005-04-27). Retrieved on 2011-08-17.

- ^ Gerstner, E. (2009). "Nuclear energy: The hybrid returns". Nature. 460 (7251): 25–8. doi:10.1038/460025a. PMID 19571861.

- ^ FusEdWeb | Fusion Education. Fusedweb.pppl.gov (1998-11-09). Retrieved on 2011-08-17.

- ^ M. Kikuchi, K. Lackner; M. Q. Tran (2012). Fusion Physics. International Atomic Energy Agency. p. 22. ISBN 9789201304100.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|lastauthoramp=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help) - ^ Subsection 4.7.4c. Kayelaby.npl.co.uk. Retrieved on 2012-12-19.

- ^ Rider, Todd Harrison (1995). "Fundamental Limitations on Plasma Fusion Systems not in Thermodynamic Equilibrium". Dissertation Abstracts International. 56–07. Massachusetts Institute of Technology, PhD Thesis: 3820. Bibcode:1995PhDT........45R.

- ^ Rostoker, Norman; Binderbauer, Michl and Qerushi, Artan. Fundamental limitations on plasma fusion systems not in thermodynamic equilibrium. fusion.ps.uci.edu

Further reading

- "What is Nuclear Fusion?". NuclearFiles.org.

- S. Atzeni; J. Meyer-ter-Vehn (2004). "Nuclear fusion reactions". The Physics of Inertial Fusion (PDF). University of Oxford Press. ISBN 978-0-19-856264-1.[dead link]

- G. Brumfiel (22 May 2006). "Chaos could keep fusion under control". Nature. doi:10.1038/news060522-2.

- R.W. Bussard (9 November 2006). "Should Google Go Nuclear? Clean, Cheap, Nuclear Power". Google TechTalks. Archived from the original on 26 April 2007.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - A. Wenisch; R. Kromp; D. Reinberger (November 2007). "Science of Fiction: Is there a Future for Nuclear?" (PDF). Austrian Institute of Ecology.

- W.J. Nuttall (September 2008). "Fusion as an Energy Source: Challenges and Opportunities" (PDF). Institute of Physics Report. Institute of Physics.

- M. Kikuchi, K. Lackner; M. Q. Tran (2012). Fusion Physics. International Atomic Energy Agency. p. 22. ISBN 9789201304100.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|lastauthoramp=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help)

External links

- NuclearFiles.org—A repository of documents related to nuclear power.

- Annotated bibliography for nuclear fusion from the Alsos Digital Library for Nuclear Issues

- [1]-NRL Fusion Formulary

- Organizations