Samuel L. Jackson

Samuel L. Jackson | |

|---|---|

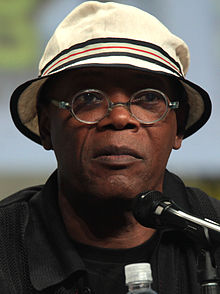

Jackson at the San Diego Comic-Con promoting Avengers: Age of Ultron in 2014 | |

| Born | Samuel Leroy Jackson December 21, 1948 Washington, D.C., U.S. |

| Alma mater | Morehouse College (B.A.) |

| Occupation(s) | Actor, film producer, comedian |

| Years active | 1972–present |

| Spouse | |

| Children | 1 |

| Website | SamuelLJackson.com |

Samuel Leroy Jackson (born December 21, 1948) is an American actor and film producer. He achieved prominence and critical acclaim in the early 1990s with films such as Jungle Fever (1991), Patriot Games (1992), Amos & Andrew (1993), True Romance (1993), Jurassic Park (1993) and his collaborations with director Quentin Tarantino including Pulp Fiction (1994), Jackie Brown (1997), Django Unchained (2012), and The Hateful Eight (2015). He is a highly prolific actor, having appeared in over 100 films, including Die Hard with a Vengeance (1995), Unbreakable (2000), Shaft (2000), The 51st State (2001), Black Snake Moan (2006), Snakes on a Plane (2006), and the Star Wars prequel trilogy (1999–2005), as well as the Marvel Cinematic Universe.

With Jackson's permission, his likeness was used for the Ultimate version of the Marvel Comics character Nick Fury. He later cameoed as the character in a post-credits scene from Iron Man (2008), and went on to sign a nine-film commitment to reprise this role in future films, including major roles in Iron Man 2 (2010), The Avengers (2012), Captain America: The Winter Soldier (2014) and Avengers: Age of Ultron (2015) and minor roles in Thor (2011) and Captain America: The First Avenger (2011). He has also portrayed the character in the second and final episodes of the first season of the TV show Marvel's Agents of S.H.I.E.L.D..

He has provided his voice to several animated films, television series and video games, including the roles of Lucius Best / Frozone in Pixar Animation Studios' film The Incredibles (2004), Mace Windu in Star Wars: The Clone Wars (2008), Afro Samurai in the anime television series Afro Samurai (2007), and Frank Tenpenny in the video game Grand Theft Auto: San Andreas (2004).

Jackson has achieved critical and commercial acclaim, surpassing Frank Welker as the actor with the highest-grossing film total of all time in October 2011,[1] and he has received numerous accolades and awards. He is married to LaTanya Richardson, with whom he has a daughter, Zoe. Samuel L. Jackson is ranked as the highest all-time box office star with over $4.9053 billion total box office gross, an average of $69.1 million per film.[2]

Early life

Jackson was born in Washington, D.C., the son of Elizabeth (née Montgomery) and Roy Henry Jackson.[3] He grew up as an only child in Chattanooga, Tennessee.[4] His father lived away from the family in Kansas City, Missouri, and later died from alcoholism. Jackson only met his father twice during his life.[5][6] Jackson was raised by his mother, who was a factory worker and later a supplies buyer for a mental institution, and by his maternal grandparents and extended family.[5][7] According to DNA tests, Jackson partially descends from the Benga people of Gabon.[8]

Jackson attended several segregated schools[9] and graduated from Riverside High School in Chattanooga. Between the third and twelfth grades, he played the French horn and trumpet in the school orchestra.[10] During childhood, he had a stuttering problem. While he eventually learned to "pretend to be other people who didn't stutter" and use the curse word motherfucker as an affirmation word, he still has days where he stutters.[11]

Initially intent on pursuing a degree in marine biology, he attended Morehouse College in Atlanta, Georgia. After joining a local acting group to earn extra points in a class, Jackson found an interest in acting and switched his major.[12] Before graduating in 1972, he co-founded the "Just Us Theatre".[5][13]

Civil Rights Movement involvement

I would like to think because of the things I did, my daughter can do the things that she does. She barely has a recognition that she's black.

—Jackson reflecting on his actions during the Civil Rights Movement[9]

After the 1968 assassination of Martin Luther King, Jr., Jackson attended the funeral in Atlanta as one of the ushers.[14] Jackson then flew to Memphis to join an equal rights protest march. In a Parade interview Jackson revealed: "I was angry about the assassination, but I wasn't shocked by it. I knew that change was going to take something different – not sit-ins, not peaceful coexistence."[15]

In 1969, Jackson and several other students held members of the Morehouse College board of trustees (including a nearby Martin Luther King, Sr.) hostage on the campus, demanding reform in the school's curriculum and governance.[16] The college eventually agreed to change its policy, but Jackson was charged with and eventually convicted of unlawful confinement, a second-degree felony.[17] Jackson was then suspended for two years for his criminal record and his actions. He would later return to the college to earn his Bachelor of Arts in Drama in 1972.[18]

While he was suspended, Jackson was employed as a social worker in Los Angeles.[19] Jackson decided to return to Atlanta, where he met with Stokely Carmichael, H. Rap Brown, and others active in the Black Power movement.[15] Jackson revealed in the same Parade interview that he began to feel empowered with his involvement in the movement, especially when the group began buying guns.[15] However, before Jackson could become involved with any significant armed confrontation, his mother sent him to Los Angeles after the FBI told her that he would die within a year if he remained with the Black Power movement.[15]

Acting career

1970s–1980s

Casting black actors is still strange for Hollywood. Denzel gets the offer first. Then it's Danny Glover, Forest Whitaker and Wesley Snipes. Right now, I'm the next one on the list.

—Jackson reacting to his new fame in 1993[19]

Jackson initially majored in marine biology at Morehouse College before switching to architecture. He later settled on drama after taking a public speaking class and appearing in a version of The Threepenny Opera.[10] Jackson began acting in multiple plays, including Home and A Soldier's Play.[5] He appeared in several television films, and made his feature film debut in the blaxploitation independent film Together for Days (1972).[20] After these initial roles, Jackson proceeded to move from Atlanta to New York City in 1976 and spent the next decade appearing in stage plays such as The Piano Lesson and Two Trains Running, which both premiered at the Yale Repertory Theater.[19][21] At this point in his early career, Jackson developed addictions to alcohol and cocaine, resulting in him being unable to proceed with the two plays as they continued to Broadway (actors Charles S. Dutton and Anthony Chisholm took his place).[18] Throughout his early film career, mainly in minimal roles in films such as Coming to America and various television films, Jackson was mentored by Morgan Freeman.[10] After a 1981 performance in the play A Soldier's Play, Jackson was introduced to director Spike Lee who would later include him in small roles for the films School Daze (1988) and Do the Right Thing (1989).[5][22] He also played a minor role in the 1990 Martin Scorsese film Goodfellas as real-life Mafia associate Stacks Edwards and also worked as a stand-in on The Cosby Show for Bill Cosby[16][23] for three years.

1990s

While completing these films, Jackson's drug addiction had worsened. After previously overdosing on heroin several times, Jackson gave up the drug in favor of cocaine.[24] After seeing the effects of his addiction, his family entered him into a New York rehab clinic.[10][25] When he successfully completed rehab, Jackson appeared in Jungle Fever, as a crack cocaine addict, a role which Jackson called cathartic as he was recovering from his addiction.[5] Jackson commented on the transition, "It was a funny kind of thing. By the time I was out of rehab, about a week or so later I was on set and we were ready to start shooting."[26] The film was so acclaimed that the 1991 Cannes Film Festival created a special "Supporting Actor" award just for him.[6][27] After this role, Jackson became involved with multiple films, including the comedy Strictly Business and dramas Juice and Patriot Games. He then moved on to two other comedies: National Lampoon's Loaded Weapon 1 (his first starring role) and Amos & Andrew.[28][29] Jackson then worked with director Steven Spielberg, appearing in Jurassic Park.[30]

After a turn as the criminal Big Don in the 1993 Quentin Tarantino-penned True Romance directed by Tony Scott, Tarantino contacted Jackson for the role of Jules Winnfield in Pulp Fiction. Jackson was surprised to learn that the part had been specifically written for him: "To know that somebody had written something like Jules for me. I was overwhelmed, thankful, arrogant – this whole combination of things that you could be, knowing that somebody's going to give you an opportunity like that."[31] Although Pulp Fiction was Jackson's thirtieth film, the role made him internationally recognized and he received praise from critics. In a review by Entertainment Weekly, his role was commended: "As superb as Travolta, Willis, and Keitel are, the actor who reigns over Pulp Fiction is Samuel L. Jackson. He just about lights fires with his gremlin eyes and he transforms his speeches into hypnotic bebop soliloquies."[32] For the Academy Awards, Miramax Films pushed for the Best Supporting Actor nomination for Jackson.[33] For his performance, Jackson received a Best Supporting Actor nomination. In addition, he received a Golden Globe nomination and won the BAFTA Award for Best Supporting Role.[34][35][36]

After Pulp Fiction, Jackson received multiple scripts to play his next role: "I could easily have made a career out of playing Jules over the years. Everybody's always sending me the script they think is the new Pulp Fiction."[37] With a succession of poor-performing films such as Kiss of Death, The Great White Hype, and Losing Isaiah, Jackson began to receive poor reviews from critics who had praised his performance in Pulp Fiction. This ended with his involvement in the two successful box office films, Die Hard with a Vengeance, starring alongside Bruce Willis in the third installment of the Die Hard series, and A Time to Kill, where he depicted a father who is put on trial for killing two men who raped his daughter.[38][39] For A Time to Kill, Jackson earned an NAACP Image for Best Supporting Actor in a Motion Picture and a Golden Globe nomination for a Best Supporting Actor.[40]

Quickly becoming a box office star, Jackson continued with three starring roles in 1997. In 187 he played a dedicated teacher striving to leave an impact on his students.[41] He received an Independent Spirit award for Best First Feature alongside first-time writer/director Kasi Lemmons in the drama Eve's Bayou, for which he also served as executive producer.[42] He joined up again with Tarantino and received the Silver Bear for Best Actor at the Berlin Film Festival[43] and a fourth Golden Globe nomination for his portrayal of arms merchant Ordell Robbie in Jackie Brown.[44] In 1998, he worked with other established actors such as Sharon Stone and Dustin Hoffman in Sphere and Kevin Spacey in The Negotiator, playing a hostage negotiator who resorts to taking hostages himself when he is falsely accused of murder and embezzlement.[45][46] In 1999, Jackson starred in the horror film Deep Blue Sea, and as Jedi Master Mace Windu in George Lucas' Star Wars: Episode I – The Phantom Menace.[47][48] In an interview, Jackson claimed that he did not have a chance to read the script for the film and did not learn he was playing the character Mace Windu until he was fitted for his costume (he later said that he was eager to accept any role, just for the chance to be a part of the Star Wars saga).[49]

2000s

On June 13, 2000, Jackson was honored with a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame at 7018 Hollywood Blvd.[50] He began the next decade in his film career as a Marine colonel put on trial in Rules of Engagement, co-starred with Bruce Willis for a third time in the supernatural thriller Unbreakable, and starred in the 2000 remake of the 1971 film Shaft.[51][52][53] Jackson's sole film in 2001 was The Caveman's Valentine, a murder thriller in which he played a homeless musician. The film was directed by Kasi Lemmons, who previously worked with Jackson in Eve's Bayou.[54] In 2002, he played a recovering alcoholic attempting to keep custody of his kids while fighting a battle of wits with Ben Affleck's character in Changing Lanes.[5] He returned for Star Wars: Episode II – Attack of the Clones, seeing his minor supporting role develop into a major character. Mace Windu's purple lightsaber in the film was the result of Jackson's suggestion;[5] he wanted to be sure that his character would stand out in a crowded battle scene.[55][56] Jackson then acted as an NSA agent alongside Vin Diesel in xXx and a kilt-wearing drug dealer in The 51st State.[57][58] In 2003, Jackson again worked with John Travolta in Basic and then as a police sergeant alongside Colin Farrell in the television show remake S.W.A.T.[59][60] A song within the soundtrack was named after him, entitled Sammy L. Jackson by Hot Action Cop.[61] Jackson also appeared in HBO's documentary Unchained Memories, as a narrator along many other stars like Angela Bassett and Whoopi Goldberg. According to reviews gathered by Rotten Tomatoes, in 2004 Jackson starred in both his lowest and highest ranked films in his career.[62] In the thriller Twisted, Jackson played a mentor to Ashley Judd.[63] The film garnered a 2% approval rating on the website, with reviewers calling his performance "lackluster" and "wasted".[64][65][66] He then lent his voice to the computer-animated film The Incredibles as the superhero Frozone.[67] The film received a 97% approval rating, and Jackson's performance earned him an Annie Award nomination for Best Voice Acting.[68][69] He then went on to do a cameo in another Quentin Tarantino film, Kill Bill: Volume 2.[70]

In 2005, he starred in the sports drama, Coach Carter, where he played a coach (based on the actual coach Ken Carter) dedicated to teaching his players that education is more important than basketball.[71] Although the film received mixed reviews, Jackson's performance was praised despite the film's storyline.[72][73] Bob Townsend of the Atlanta Journal-Constitution commended Jackson's performance, "He takes what could have been a cardboard cliche role and puts flesh on it with his flamboyant intelligence."[74] Jackson also returned for two sequels: XXX: State of the Union, this time commanding Ice Cube, and the final Star Wars prequel film, Star Wars: Episode III – Revenge of the Sith.[75][76] His last film for 2005 was The Man alongside comedian Eugene Levy.[77] On November 4, 2005, he was presented with the Hawaii International Film Festival Achievement in Acting Award.[78]

On January 30, 2006, Jackson was honored with a hand and footprint ceremony at Grauman's Chinese Theater; he is the seventh African American and 191st actor to be recognized in this manner.[79] He next starred opposite actress Julianne Moore in the box office bomb Freedomland, where he depicted a police detective attempting to help a mother find her abducted child while quelling a citywide race riot.[80][81] Jackson's second film of the year, Snakes on a Plane, gained cult film status months before it was released based on its title and cast.[82] Jackson's decision to star in the film was solely based on the title.[83] To build anticipation for the film, he also cameoed in the 2006 music video "Snakes on a Plane (Bring It)" by Cobra Starship. On December 2, 2006, Jackson won the German Bambi Award for International Film, based on his many film contributions.[84] In December 2006, Jackson starred in Home of the Brave, as a doctor returning home from the Iraq War.[85]

On January 30, 2007, Jackson was featured as narrator in Bob Saget's direct-to-DVD Farce of the Penguins.[86] The film was a spoof of the box office success March of the Penguins (which was narrated by Morgan Freeman).[87] Also in 2007, he portrayed a blues player who imprisons a young woman (Christina Ricci) addicted to sex in Black Snake Moan, and the horror film 1408, an adaptation of the Stephen King short story.[88][89] Later the same year, Jackson portrayed an athlete who impersonates former boxing heavyweight Bob Satterfield in director Rod Lurie's drama, Resurrecting the Champ. In 2008, Jackson reprised his role of Mace Windu in the CGI film, Star Wars: The Clone Wars, followed by Lakeview Terrace where he played a racist cop who terrorizes an interracial couple.[90][91] In November of the same year, he starred along with Bernie Mac and Isaac Hayes (who both died before the film's release) in Soul Men.[92] In 2008, he portrayed the villain in The Spirit, which was poorly received by critics and the box office.[93][94] In 2009, he again worked with Quentin Tarantino when he narrated several scenes in the World War II film, Inglourious Basterds.[95]

2010s

In 2010, he starred in the drama Mother and Child and portrayed an interrogator who attempts to locate several nuclear weapons in the direct-to-video film Unthinkable.[96][97] Alongside Dwayne Johnson, Jackson again portrayed a police officer in the opening scenes of the comedy The Other Guys. He also co-starred with Tommy Lee Jones for a film adaptation of The Sunset Limited.

Throughout Jackson's career, he has appeared in many films alongside mainstream rappers. These include Tupac Shakur (Juice), Queen Latifah (Juice/Sphere/Jungle Fever), Method Man (One Eight Seven), LL Cool J (Deep Blue Sea/S.W.A.T.), Busta Rhymes (Shaft), Eve (xXx), Ice Cube (xXx: State of the Union), Xzibit (xXx: State of the Union), David Banner (Black Snake Moan), and 50 Cent (Home of the Brave).[98] Additionally, Jackson has appeared in four films with actor Bruce Willis (National Lampoon's Loaded Weapon 1, Pulp Fiction, Die Hard with a Vengeance, and Unbreakable) and the actors were slated to work together in Black Water Transit before both dropped out.[99]

In 2002, Jackson gave his consent for Marvel Comics to design their "Ultimate" version of the character Nick Fury after his likeness.[100] In the 2008 film Iron Man, he made a cameo as the character in a post-credit scene.[101] In February 2009, Jackson signed on to a nine-picture deal with Marvel which would see him appear as the character in Iron Man 2, Thor, Captain America: The First Avenger, and The Avengers as well as any other sequels they would produce.[102] He reprised the role in Captain America: The Winter Soldier (2014)[103] and Avengers: Age of Ultron (2015).[104] Jackson said in an interview on February 11, 2015, that he only has two movies left on his Marvel contract following Ultron.[105]

Among his more recent film roles, Jackson appeared in Quentin Tarantino's Django Unchained, which was released December 25, 2012,[106] Tarantino's The Hateful Eight, which was released in 70mm on December 25, 2015,[107] and Jordan Vogt-Roberts' Kong: Skull Island,[108] which was released on March 10, 2017.

Upcoming films

Jackson is set to produce a live-action film adaptation of Afro Samurai,[109] and is assuming the role of Sho'nuff in a remake of The Last Dragon.[110] He will also star in the Brie Larson film Unicorn Store.[111][112] Jackson is featured in Eating You Alive, a 2016 American documentary about food and health.

Television and other roles

In addition to films, Jackson also appeared in several television shows, a video game, music videos, as well as audiobooks. Jackson had a small part in the Public Enemy music video for "911 Is a Joke". Jackson voiced several television show characters, including the lead role in the anime series, Afro Samurai, in addition to a recurring part as the voice of Gin Rummy in several episodes of the animated series The Boondocks.[113][114] He guest-starred as himself in an episode of the BBC/HBO sitcom Extras.[115] He voiced the main antagonist, Officer Frank Tenpenny, in the video game Grand Theft Auto: San Andreas.[116] Jackson also hosted a variety of awards shows. He has hosted the MTV Movie Awards (1998),[117] the ESPYs (1999, 2001, 2002, and 2009),[118] and the Spike TV Video Game Awards (2005, 2006, 2007, and 2012).[119] In November 2006, he provided the voice of God for The Bible Experience, the New Testament audiobook version of the Bible. He was given the lead role because producers believed his deep, authoritative voice would best fit the role.[120] He also recorded the Audible.com audiobook of Go the Fuck to Sleep.[121] For the Atlanta Falcons' 2010 season, Jackson portrayed Rev. Sultan in the Falcons "Rise Up" commercial. He reprised his role as Nick Fury in a cameo appearance on Agents of S.H.I.E.L.D. in 2013[122] and the season finale in 2014,[123] and appeared in Capital One cash-back credit card commercials.

He released a song about social justice with KRS-One, Sticky Fingaz, Mad Lion & Talib Kweli about violence in America called "I Can't Breathe" which were the last words said by Eric Garner.[124]

Box office performance

Jackson has said that he chooses roles that are "exciting to watch" and have an "interesting character inside of a story", and that in his roles he wanted to "do things [he hasn't] done, things [he] saw as a kid and wanted to do and now [has] an opportunity to do".[125] Throughout the 1990s, A.C. Neilson E.C.I., a box office tracking company, determined that Jackson appeared in more films than any other actor that grossed $1.7 billion domestically.[126] For all the films in his career, where he is featured as a leading actor or supporting co-star, his films have grossed a total of $2.81[127] to $4.91 billion[128] at the North American box office, placing him as the seventh (as strictly lead) or the second highest-grossing movie star (counting supporting roles) of all time; behind only that of voice actor Frank Welker. The 2009 edition of The Guinness World Records, which uses a different calculation to determine film grosses, stated that Jackson is the world's highest grossing actor, having earned $7.42 billion in 68 films.[129]

Filmography

Personal life

In 1980, Jackson married actress and sports channel producer LaTanya Richardson,[130] whom he met while attending Morehouse College.[5] The couple have a daughter, Zoe (born 1982).[131] In 2009, they started their own charitable organization to help support education.[130] Jackson has said he attends each of his films in theaters with paying customers, saying: "Even during my theater years, I wished I could watch the plays I was in – while I was in them! I dig watching myself work."[132] He also enjoys collecting the action figures of the characters he portrays in his films, including Jules Winnfield, Shaft, Mace Windu, and Frozone.[133]

Jackson is bald but enjoys wearing wigs in his films.[134] He said about his decision to go bald: "I keep ending up on those bald is beautiful lists. It's cool. You know, when I started losing my hair it was during the era when everybody had lots of hair. All of a sudden I felt this big hole in the middle of my afro, I couldn't face having a comb over so I had to quickly figure what the haircut for me was."[134] His first bald role was in The Great White Hype.[135] He usually gets to pick his own hairstyles for each character he portrays.[135][136] He poked fun at his baldness the first time he appeared bald on The Tonight Show, explaining that he had to shave his head for one role, but then kept receiving more and more bald roles and had to keep shaving his head so that wigs could be made for him. He joked that "the only way I'm gonna have time to grow my hair back is if I'm not working".

Jackson has a clause in his film contracts that allows him to play golf during film shoots.[9][34] He has played in the Gary Player Invitational charity golf tournament to assist Gary Player in raising funds for children in South Africa.[10] Jackson is a keen basketball fan, supporting the Toronto Raptors and the Harlem Globetrotters.[137] He supports the soccer team Liverpool F.C. since appearing in The 51st State.[138] He also supports Irish soccer team Bohemian F.C.

Jackson campaigned during the 2008 Democratic Primary for Barack Obama in Texarkana, Texas. He said: "Barack Obama represents everything I was told I could be growing up. I am a child of segregation. When I grew up and people told me I could be president, I knew it was a lie. But now we have a representative... the American Dream is a reality. Anyone can grow up to be a president."[139] Jackson also said: "I voted for Barack because he was black. That's why other folks vote for other people – because they look like them".[140][141] He compared his Django Unchained character, a villainous house slave, to black conservative Justice Clarence Thomas, saying that "I have the same moral compass as Clarence Thomas does".[142]

In June 2013, Jackson launched a joint campaign with the charity Prizeo in an effort to raise money to fight Alzheimer's disease. As part of the campaign, he recited various fan-written monologues and a popular scene from the AMC series Breaking Bad.[143][144] In August 2013, he started a vegan diet for health reasons, explaining that he is "just trying to live forever",[145] and attributes a 40 lb weight loss to his new diet.[146] He launched a campaign called "One for the Boys", which teaches men about testicular cancer and urges them to "get themselves checked out".[147][148]

See also

References

- ^ Powers, Lindsay (October 27, 2011). "Samuel L. Jackson Is Highest-Grossing Actor of All Time". The Hollywood Reporter. Retrieved January 6, 2012.

- ^ "People Index." Box Office Mojo.

- ^ "Finding Your Roots". google.ca. Retrieved May 18, 2015.

- ^ "Samuel Jackson Figures He Owes His Success to Morgan Freeman" (Fee required). Deseret News. March 2, 1993. Retrieved January 24, 2010.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i "Episode #8.15". Inside the Actors Studio. Season 8. Episode 15. June 2, 2002.

{{cite episode}}: Unknown parameter|serieslink=ignored (|series-link=suggested) (help) - ^ a b Rochlin, Margy (November 2, 1997). "Tough Guy Finds His Warm and Fuzzy Side". The New York Times. Retrieved May 10, 2009.

- ^ Kay, Karen (October 13, 2004). "From coke addict to golf addict: How Samuel L Jackson found salvation on fairways to heaven". The Independent. London. Retrieved May 10, 2009.

- ^ "Jackson Rice Simmons Finding Your Roots". genealogy-research-tools.com. Retrieved April 16, 2013.

- ^ a b c Beale, Lewis (June 11, 2000). "Clean Break With the Past – Samuel L. Jackson went from addict to Hollywood star". Daily News. Retrieved January 25, 2010. [dead link]

- ^ a b c d e "Samuel L. Jackson Biography". tiscali. Retrieved May 10, 2009.

- ^ Vineyard, Jennifer (June 4, 2013). "Which Curse Word Does Samuel L. Jackson Credit With Stopping His Stutter?". Vulture.com. New York Media, LLC. Retrieved June 17, 2015.

- ^ Hudson 2004, p. 23

- ^ Edelman, Rob. "Samuel L. Jackson". Film Reference. Retrieved May 10, 2009.

- ^ Smiley, Tavis (February 24, 2006). "Samuel L. Jackson". The Tavis Smiley Show. Archived from the original on June 12, 2009. Retrieved May 10, 2009.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ a b c d Rader, Dotson (January 9, 2005). "He Found His Voice (Film actor Samuel L. Jackson)". Parade. Archived from the original on December 29, 2008. Retrieved May 10, 2009.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ a b Kung, Michelle (February 12, 2006). "Action Jackson". The Boston Globe. Retrieved May 10, 2009.

- ^ O'Hagan, Sean (December 7, 2008). "Samuel L Jackson: 'Now we got the movie stuff out of the way, let's talk about something serious'". The Guardian. London. Retrieved June 5, 2009.

- ^ a b "Samuel L. Jackson". Yahoo Movies.com. Retrieved May 10, 2009.

- ^ a b c Petrakis, John (February 24, 1993). "Reaching for the top Veteran actor Samuel Jackson more than just a familiar face". Chicago Tribune. Retrieved May 10, 2009. (registration required)

- ^ Angeli, Michael (February 19, 1993). "Samuel Jackson is quite the character" (Fee required). The Dallas Morning News. Retrieved January 24, 2010.

- ^ Hudson 2004, p. 32

- ^ Hudson 2004, p. 41

- ^ Hudson 2004, p. 53

- ^ Hudson 2004, p. 65

- ^ Hudson 2004, p. 66

- ^ Hudson 2004, p. 71

- ^ "Festival de Cannes: Jungle Fever". festival-cannes.com. Retrieved January 24, 2010.

- ^ Ryan, James (April 28, 1995). "Jackson Out of Hiding". Ocala Star-Banner. Google News. Retrieved January 26, 2010.

- ^ Petrakis, John (February 24, 1993). "Reaching for the top Veteran actor Samuel Jackson more than just a familiar face" (Fee required). Chicago Tribune. Retrieved January 26, 2010.

- ^ Price, Michael H. (June 14, 1993). "'Jurassic Park' Thriller Not Necessarily For Kids". TimesDaily. Google News. Retrieved January 24, 2010.

- ^ Hudson 2004, p. 99

- ^ Hudson 2004, p. 106

- ^ Hudson 2004, p. 5

- ^ a b Bhattacharya, Sanjiv (October 27, 2002). "Play it again Samuel..." The Observer. London. Retrieved May 10, 2009.

- ^ "'Gump' Tops Golden Globe Nominations". The New York Times. December 24, 1994. Retrieved May 10, 2009.

- ^ Okwu, Michael (March 1, 2001). "Samuel L. Jackson not caving in to star pressure". CNN. Retrieved May 10, 2009.

- ^ Hudson 2004, p. 121

- ^ "A Time to Kill". Box Office Mojo. Retrieved January 26, 2010.

- ^ "Die Hard: With a Vengeance". Box Office Mojo. Retrieved January 26, 2010.

- ^ Ryan, Tim (November 5, 2005). "Working It". Honolulu Star-Bulletin. Retrieved May 10, 2009.

- ^ Guthmann, Edward (July 30, 1997). "Really Dangerous Minds in '187'". San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved January 25, 2010.

- ^ Wallace, Amy (January 9, 1998). "Duvall's 'Apostle' Truly Filled With Spirit; Movies: 'Hard Eight,' 'Star Maps' and 'Ulee's Gold' follow in the nominations honoring independent films". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved May 10, 2009.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|registration=ignored (|url-access=suggested) (help) - ^ "Berlinale: 1998 Prize Winners". berlinale.de. Retrieved January 16, 2012.

- ^ Malcolm, Derek (February 23, 1998). "Brazilian wins Berlin film prize with odyssey of an orphan". The Guardian. Retrieved May 10, 2009.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|registration=ignored (|url-access=suggested) (help) - ^ Michael, Dennis (February 13, 1998). "'Sphere' takes moviegoers to new depths". CNN. Retrieved January 25, 2010.

- ^ Gleiberman, Owen (July 31, 1998). "The Negotiator (1998)". Entertainment Weekly. Retrieved January 25, 2010.

- ^ LaSalle, Mick (July 31, 1998). "These Sharks Have Attitude – 'Deep Blue Sea' a Fresh, Tasty Thriller". San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved January 25, 2010.

- ^ Spelling, Ian (July 31, 1998). "The Force is With Jackson". Reading Eagle. Google News. Retrieved January 25, 2010.

- ^ Walters, Mark (July 2006). "Samuel L. Jackson talks Snakes on a Plane". BigFanBoy.com. Retrieved May 10, 2009.

- ^ "Locations of Stars on the Hollywood Walk of Fame". Hollywood Walk of Fame. Archived from the original on May 14, 2009. Retrieved May 10, 2009.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Germain, David (April 8, 2000). "'Engagement' Bumps 'Brockovich'". Spartanburg Herald-Journal. Google News. Retrieved January 26, 2010.

- ^ Tucker, Ken (November 28, 2000). "Stand Up, Comics!". Entertainment Weekly. Retrieved January 26, 2010.

- ^ Rush, George; Molloy, Joanna; Ogunnaike, Lola; Robinovitz, Karen (June 8, 2000). "Jackson: 'Shaft' Drove Me Daft". Daily News. Archived from the original on July 30, 2012. Retrieved January 26, 2010.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Schwarzbaum, Lisa (March 7, 2001). "The Caveman's Valentine (2001)". Entertainment Weekly. Retrieved January 26, 2010.

- ^ Hudson 2004, p. 219

- ^ Giles, Jeff (May 7, 2002). "Samuel L. Jackson on the Hilarious Origins of His Purple Lightsaber in 'Star Wars'". Townsquare Media. Oaktree Capital Management. Retrieved June 16, 2015.

- ^ "License to Thrill". Sydney Morning Herald. August 30, 2002. Retrieved January 26, 2010.

- ^ "Formula 51 (2002)". Entertainment Weekly. August 20, 2002. Retrieved January 26, 2010.

- ^ Bentley, Rick (March 22, 2003). "'Basic' Travolta". Toledo Blade. Google News. Retrieved January 26, 2010.

- ^ "'S.W.A.T.' tops weekend box office". USA Today. Associated Press. August 10, 2003. Retrieved January 26, 2010.

- ^ "Hot Action Cop in TV, Movies and Video Games". Hot Action Cop. Archived from the original on December 27, 2007. Retrieved May 10, 2009.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Samuel L. Jackson". Rotten Tomatoes. Retrieved January 26, 2010.

- ^ Sragow, Michael (March 7, 2004). "The McQueen of Women-In-Jeopardy Films" (Fee required). The Baltimore Sun. Retrieved January 26, 2010.

- ^ "Twisted (2004)". Rotten Tomatoes. Retrieved January 26, 2010.

- ^ Schager, Nick (February 26, 2004). "Twisted". Slant Magazine. Retrieved January 26, 2010.

- ^ Lane, Jim (March 11, 2004). "Twisted". Sacramento News & Review. Retrieved January 26, 2010.

- ^ Burr, Ty (November 5, 2004). "Look! Up in the sky! It's a flabby suburban dad!". Boston Globe. Retrieved January 26, 2010.

- ^ "The Incredibles (2004)". Rotten Tomatoes. Retrieved January 26, 2010.

- ^ "Annie Award Noms Incredibly Good To 'Incredibles'". KIRO-TV. December 8, 2004. Archived from the original on April 20, 2005. Retrieved January 26, 2010.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Burr, Ty (April 16, 2004). "Second 'Kill Bill' is dead-on". Boston Globe. Retrieved January 26, 2010.

- ^ Daly, Sean (January 14, 2005). "In 'Carter,' Jackson Calls the Shots". The Washington Post. Retrieved January 26, 2010.

- ^ Foucher, David (January 14, 2005). "Coach Carter". EDGE. Retrieved January 26, 2010.

- ^ Tucker, Betty Jo. "Winning a Future". ReelTalk Movie Reviews. Retrieved January 26, 2010.

- ^ Townsend, Bob. "Coach Carter". Atlanta Journal-Constitution. Archived from the original on May 12, 2008. Retrieved January 26, 2010.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Time For a Lads Night Out". The Sun. August 12, 2008. Retrieved January 26, 2010.

- ^ Turan, Kenneth (May 15, 2005). "'Star Wars: Episode III Revenge of the Sith'". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on May 23, 2008. Retrieved January 26, 2010.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Hart, Hugh (September 11, 2005). "Non-Action Hero Gets Top Billing". San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved January 25, 2010.

- ^ "Samuel L. Jackson to receive acting award". USA Today. Associated Press. November 6, 2005. Retrieved May 10, 2009.

- ^ "Actor Jackson enters Walk of Fame". BBC News. January 31, 2006. Retrieved May 10, 2009.

- ^ "Freedomland". Box Office Mojo. Retrieved January 26, 2010.

- ^ Gleiberman, Owen (February 17, 2006). "'Freedomland' shrill and joyless". Entertainment Weekly. CNN. Retrieved January 26, 2010.

- ^ Elsworth, Catherine (March 25, 2006). "Cult film fans are bitten by Snakes on a Plane". The Daily Telegraph. London. Retrieved January 26, 2010.

- ^ Tyrangiel, Josh (April 24, 2006). "Snakes on Samuel L. Jackson". Time. Retrieved May 10, 2009.

- ^ "Bambi honour for Jackson". ITV News. Archived from the original on February 6, 2009. Retrieved May 10, 2009.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Germain, David (December 14, 2006). "Trite script wins battle in 'Home of the Brave'". MSNBC. Associated Press. Retrieved January 24, 2010.

- ^ Palathingal, George (August 2, 2007). "Farce of the Penguins". The Sydney Morning Herald. Retrieved January 24, 2010.

- ^ "Samuel L. Jackson: 'I'm fine with snakes'". MSNBC. Associated Press. August 18, 2006. Retrieved January 24, 2010.

- ^ Johnson, Ross (April 23, 2006). "Hollywood's One Remaining Taboo Found in 'Black Snake Moan'". The New York Times. Retrieved January 24, 2010.

- ^ Thomson, Desson (June 22, 2007). "Creepy '1408': It's Worth Checking Into". The Washington Post. Retrieved January 24, 2010.

- ^ Germain, David (August 11, 2008). "Review: 'Clone Wars' is fun though forgettable". USA Today. Retrieved January 24, 2010.

- ^ Germain, David (January 29, 2009). "DVD reviews: 'Lakeview Terrace,' 'Fireproof'". MSNBC. Associated Press. Retrieved January 24, 2010.

- ^ Bowles, Scott (August 14, 2008). "For 'Soul Men' director, deaths of Mac, Hayes were doubly devastating". USA Today. Retrieved January 24, 2010.

- ^ "The Spirit". Rotten Tomatoes. Retrieved January 24, 2010.

- ^ "The Spirit". Box Office Mojo. Retrieved January 24, 2010.

- ^ LaSalle, Mick (August 20, 2009). "WWII rewritten in glorious Basterds". Houston Chronicle. Retrieved January 24, 2010.

- ^ Boucher, Geoff (January 24, 2009). "Samuel L. Jackson is animated about 'Afro Samurai: Resurrection'". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved May 10, 2009.

- ^ "Samuel L. Jackson enjoyed violent scene". Boston Globe. February 15, 2009. Retrieved May 10, 2009.

- ^ Silberman, Stacey (August 27, 2007). "Samuel L. Jackson: Man of Many Digital Faces". Hollywood Today. Retrieved January 26, 2010.

- ^ Carroll, Larry; Adler, Shawn; Horowitz, Josh (January 26, 2007). "Sam Jackson Reunites With Willis, 'Underdog' Gets Real: Sundance File". MTV. Retrieved January 26, 2010.

- ^ Boucher, Geoff (January 13, 2009). "Nick Fury no more? Samuel L. Jackson says 'Maybe I won't be Nick Fury'". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved May 10, 2009.

- ^ Vary, Adam B.; Collis, Clark (May 9, 2008). "Striking While Iron Man is Hot". Entertainment Weekly. Retrieved January 25, 2010.

- ^ Kit, Borys (February 25, 2009). "Jackson's Fury in flurry of Marvel films". Reuters. The Hollywood Reporter. Retrieved November 9, 2010.

- ^ Sneider, Jeff (June 6, 2012). "Russo brothers tapped for 'Captain America 2': Disney and Marvel in final negotiations with 'Community' producers to helm pic". Variety. Archived from the original on August 4, 2012. Retrieved July 3, 2012.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Lealos, Shawn S. (February 12, 2015). "Samuel L. Jackson Has 2 Movies Left in his Marvel Contract". Renegade Cinema. Retrieved February 12, 2015.

- ^ Brew, Simon (February 12, 2015). "Samuel L Jackson's Marvel contract has two films left". Den of Geek. Dennis Publishing. Retrieved August 3, 2016.

- ^ "Will Smith Could Be DJANGO UNCHAINED, Samuel L. Jackson Cast". WhatCulture.com. Archived from the original on May 9, 2011. Retrieved May 18, 2015.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ McNary, Dave (December 26, 2015). "Quentin Tarantino's 'Hateful Eight' Launches With $1.9 Million on Christmas". Variety. Retrieved January 7, 2016.

- ^ Fleming, Jr, Mike (August 6, 2015). "Is There Room On 'Kong: Skull Island' For Samuel L. Jackson And Tom Wilkinson?". Deadline.

- ^ O'Connell, Sean (July 22, 2011). "Samuel L. Jackson Producing A Live-Action Afro Samurai Movie". Cinema Blend. Retrieved April 16, 2013.

- ^ Simmons, Leslie (October 30, 2008). "Samuel L. Jackson vs. the 'Dragon'". The Hollywood Reporter. Archived from the original on November 2, 2008. Retrieved October 30, 2008.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Hipes, Patrick (November 14, 2016). "Samuel L. Jackson, Joan Cusack & Bradley Whitford Join Brie Larson's 'Unicorn Store'". Deadline.com. Retrieved November 14, 2016.

- ^ McNary, Dave (November 14, 2016). "Samuel L. Jackson, Joan Cusack, Bradley Whitford Join Brie Larson's 'Unicorn Store'". Variety. Retrieved November 14, 2016.

- ^ "Samuel L. Jackson to give a voice to 'Afro Samurai'". The Herald-Mail. May 4, 2005. Retrieved January 26, 2010.

- ^ Weisman, Jon (May 13, 2006). "Why thesps can't laugh off animated voice gigs". Variety. Archived from the original on February 18, 2009. Retrieved January 26, 2010.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "A-listers flock to Gervais sitcom". BBC News. January 24, 2005. Retrieved January 26, 2010.

- ^ Vargas, Jose Antonio (December 15, 2004). "Major Players". The Washington Post. Retrieved January 26, 2010.

- ^ "Wallflowers, Imbruglia Set For MTV Movie Awards". Rolling Stone. May 16, 1998. Retrieved January 25, 2010.

- ^ "Samuel L. Jackson returns as ESPY Awards host". Los Angeles Times. April 7, 2009. Retrieved January 25, 2010.

- ^ Hutchens, Bill (April 29, 2008). "Having a Grand Theft time" (Fee required). The News Tribune. Retrieved January 25, 2010.

- ^ "Jackson Voices God". ContactMusic.com. July 16, 2006. Retrieved May 10, 2009.

- ^ Netburn, Deborah (June 15, 2011). "Samuel L. Jackson reads 'Go the F --- to Sleep'". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved June 18, 2011.

- ^ "0-8-4". Agents of S.H.I.E.L.D. Season 1. Episode 2. October 1, 2013. ABC.

- ^ "Beginning of the End". Agents of S.H.I.E.L.D. Season 1. Episode 22. May 13, 2014. ABC.

- ^ Samuel L Jackson conscious song

- ^ Dawson, Angela (August 25, 2006). "Samuel L. Jackson shares some of his thoughts on acting, his new movie and his biggest phobia". Sun2Surf. Archived from the original on February 7, 2009. Retrieved May 10, 2009.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Hudson 2004, p. 213

- ^ "People Index". Box Office Mojo. Retrieved January 3, 2011.

- ^ "All Time Top 100 Stars at the Box Office". The Numbers. Retrieved January 3, 2011.

- ^ Dwinell, Joe (September 16, 2008). "Brangelina take over the 'World'". Boston Herald. Archived from the original on September 18, 2008. Retrieved May 10, 2009.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|dead-url=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|registration=ignored (|url-access=suggested) (help) - ^ a b Mears, Jo (May 23, 2009). "My family values". The Guardian. London. Retrieved January 26, 2010.

- ^ Williams, Lena (June 9, 1991). "Samuel L. Jackson: Out of Lee's 'Jungle,' Into the Limelight". The New York Times. Retrieved May 10, 2009.

- ^ Tyrangiel, Josh (August 7, 2006). "His Own Best Fan". Time. Retrieved May 10, 2009.

- ^ Miller, Prairie (May 18, 2005). "Celebrity Spotlight: Samuel L. Jackson". LongIslandPress.com. Archived from the original on November 19, 2005. Retrieved May 10, 2009.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ a b "Samuel L. Jackson's bald love". Monsters and Critics. October 13, 2007. Archived from the original on September 7, 2008. Retrieved May 10, 2009.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ a b Walton, A. Scott (October 21, 2002). "Wigs Often Play Supporting Roles in Films With Samuel L. Jackson" (Fee required). The Atlanta Journal-Constitution. Retrieved January 26, 2010.

- ^ Alvarez, Antoinette (February 14, 2007). "Interview: Samuel L. On Black Snake Moan". LatinoReview.com. Archived from the original on August 15, 2015. Retrieved May 10, 2009.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Govani, Shinan (November 4, 2006). "Raptors provide Jackson's action". The Windsor Star. Retrieved May 10, 2009.

- ^ "Samuel L Jackson enjoys Liverpool's 5-1 win over Arsenal". Liverpool Echo. February 9, 2014. Retrieved May 17, 2015.

- ^ Martin, Marie (February 25, 2008). "Jackson campaigns for Obama". Texarkana Gazette. Archived from the original on July 17, 2011. Retrieved June 9, 2010.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Samuel L. Jackson: 'I Voted for Barack Because He Was Black'". Yahoo! News. February 11, 2012.

- ^ "Politics of color". New York Post. February 11, 2012. Retrieved February 19, 2013.

- ^ Ryzik, Melena. Supporting Actor Category Is Thick With Hopefuls, New York Times (December 19, 2012).

- ^ Matheson, Whitney (June 6, 2013). "Samuel L. Jackson does 'Breaking Bad'". USA Today. Retrieved June 14, 2013.

- ^ Maglio, Tony; Reuters (June 11, 2013). "Samuel L. Jackson's 'Breaking Bad' monologue is just the beginning for charity platform prizeo". Chicago Tribune. Retrieved June 14, 2013.

{{cite web}}:|author2=has generic name (help) - ^ "Samuel L Jackson on his 9 movie Marvel contract". Yahoo! Movies. Yahoo!. Retrieved September 2, 2014.

- ^ Ivan-Zadeh, Larushka (March 28, 2014). "Samuel L Jackson: As a young black actor, my character always died". Metro News. Retrieved September 2, 2014.

- ^ "Samuel L Jackson's testicular cancer awareness video is passionate and slightly menacing". Retrieved April 24, 2014.

- ^ "One For The Boys".

Further reading

- Dils, Tracey E. (1999). Samuel L. Jackson. Black Americans of Achievement. Philadelphia: Chelsea House Publications. ISBN 0-7910-5282-6. OCLC 41885637.

- Hudson, Jeff (2004). Samuel L. Jackson: The Unauthorised Biography. London: Virgin Books. ISBN 1-85227-024-1. OCLC 224038091.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Jordan, Pat (April 26, 2012). "How Samuel L. Jackson Became His Own Genre". The New York Times.

External links

- Official website

- Samuel L. Jackson at IMDb

- Samuel L. Jackson at the Internet Broadway Database

- Template:Mojo name

- Samuel L. Jackson collected news and commentary at The New York Times

- Samuel L. Jackson collected news and commentary at The Guardian

- Extensive biography of Samuel L. Jackson

- 1948 births

- American people of Benga descent

- American people of Gabonese descent

- 20th-century American male actors

- 21st-century American male actors

- Male actors from Tennessee

- Male actors from Washington, D.C.

- Activists for African-American civil rights

- African-American male actors

- African-American television producers

- African-American film producers

- American male video game actors

- American male voice actors

- American male film actors

- Best Supporting Actor BAFTA Award winners

- Independent Spirit Award for Best Male Lead winners

- Living people

- Morehouse College alumni

- People from Chattanooga, Tennessee

- Silver Bear for Best Actor winners

- American male television actors