Dengue fever: Difference between revisions

I've quickly gone through to correct the more egregious factual infelicities. The whole article needs a rewrite. In particular, the epidemioly section with outbreak numbers is not a very good overview |

m clean up using AWB |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{Redirect|Dengue Fever|the band of the same name|Dengue Fever (band)}} |

{{Redirect|Dengue Fever|the band of the same name|Dengue Fever (band)}} |

||

{{Infobox disease |

{{Infobox disease |

||

| Name = Dengue fever |

|||

| Image = Denguerash.JPG |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | |||

Denguerash.JPG| |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | |||

}} |

}} |

||

{{Taxobox |

{{Taxobox |

||

Revision as of 14:01, 13 December 2010

| Dengue fever | |

|---|---|

| Specialty | Infectious diseases |

| Dengue virus | |

|---|---|

| |

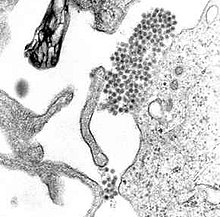

| A TEM micrograph showing Dengue virus virions (the cluster of dark dots near the center). | |

| Virus classification | |

| Group: | Group IV ((+)ssRNA)

|

| Family: | |

| Genus: | |

| Species: | Dengue virus

|

Dengue fever (pronounced English pronunciation: /ˈdɛŋɡeɪ/, English pronunciation: /ˈdɛŋɡiː/) and dengue hemorrhagic fever (DHF) are among the spectrum of acute febrile diseases caused by the dengue virus and transmitted by mosquitoes. Dengue infection which occurs mainly in the tropics, can be life-threatening, and are caused by four closely related virus serotypes of the genus Flavivirus, family Flaviviridae.[1] It was identified and named in 1779. It is also known as breakbone fever, since it typically causes a severe generalised bodyache. Unlike malaria, dengue is tends to be more prevalent in the urban districts of its range than in rural areas. Each serotype is sufficiently different that there is no long-term cross-protection and multiple serotypes can can co-exist in one area, known as hyperendemicity, though epidemics tend to be dominated by a single serotype, often newly introduced into a region. Dengue is transmitted to humans by the Aedes (Stegomyia) aegypti or more rarely the Aedes albopictus mosquito. The mosquitoes that spread dengue usually bite at dusk and dawn but may bite at any time during the day, especially indoors, in shady areas, or when the weather is cloudy.[2]

The WHO says some 2.5 billion people, two fifths of the world's population, are now at risk from dengue and estimates that there may be 50 million cases of dengue infection worldwide every year. The disease is now endemic in more than 100 countries.[3] Recent autochthonous transmission in Florida, Queensland, France and Italy highlight the potential for the increase in the range of dengue with the presence of competent vectors (principally Aedes albopictus) in the Mediterranean and subtropical areas of America and Australia.

Signs and symptoms

The disease manifests as fever of sudden onset associated with headache, muscle and joint pains (myalgias and arthralgias—severe pain that gives it the nickname break-bone fever or bonecrusher disease), distinctive retro-orbital pain, and rash.[4]

The classic dengue rash is a generalised maculopapular rash with islands of sparing. A hemorrhagic rash of characteristically bright red pinpoint spots, known as petechiae can occur later during the illness and is associated with thrombocytopenia. It usually appears first on the lower limbs and the chest; in some patients, it spreads to cover most of the body. There may also be severe retro-orbital pain, (a pain from behind the eyes that is distinctive to Dengue infections), and gastritis with some combination of associated abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting coffee-grounds-like congealed blood, or diarrhea.

Some cases develop much milder symptoms which can be misdiagnosed as influenza or other viral infection when no rash or retro-orbital pain is present. Febrile travelers from tropical areas may transmit dengue inadvertently to previously Dengue free populations with mosquitoes capable of carrying the virus, as documented in Europe. Patients only transmit Dengue when they are carrying virus in the blood and are bitten by suitable mosquitoes (typically when they are having a fever), or (much more unusually) via blood products.

The classic dengue fever lasts about two to seven days, sometimes with a smaller peak of fever at the trailing end of the disease (the so-called "biphasic pattern"). Recovery may be associated with prolonged fatigue and depression.[5] Clinically, the platelet count will drop until after the patient's temperature is normal. Some practicing doctors have observed that platelet counts typically reach their lowest point around the fifth or sixth day from the onset of the fever, with the platelet count stabilizing for 24 to 48 hours before beginning to rise once again. Many patients often assume that once the fever has stopped that they are cured. However, platelet counts at this point often continues to drop before stabilizing--necessitating continuous monitoring of platelet counts and continuous hydration, until the patient's platelet counts begin rising once again.

Cases of DHF may show variable hemorrhagic phenomena including bleeding from the eyes, nose, mouth, ear, into the gut, bruising, petechiae (pin-point bleeding from capillaries visible on the skin), thrombocytopenia, and hemoconcentration. When Dengue infections progress to DHF, typically there is significant vascular leak which involves fluid in the blood vessels leaking out into connective tissue spaces, for example around the lungs and abdomen. This fluid loss and severe bleeding can cause blood pressure to fall; then Dengue Shock Syndrome (DSS) sets in, which has a high mortality rate.

Neurological manifestations such as encephalitis may also occur .[6]

Virology

Dengue fever is caused by Dengue virus (DENV), a mosquito-borne flavivirus. DENV is an ssRNA positive-strand virus of the family Flaviviridae; genus Flavivirus. There are four serotypes of DENV. The virus has a genome of about 11000 bases that codes for three structural proteins, C, prM, E; seven nonstructural proteins, NS1, NS2a, NS2b, NS3, NS4a, NS4b, NS5; and short non-coding regions on both the 5' and 3' ends.[7]. Further classification of each serotype into genotypes often relates to the region where particular strains are commonly found or were first found.

E protein

The DENV E (envelope) protein, found on the viral surface, is important in the initial attachment of the viral particle to the host cell. Several molecules which interact with the viral E protein (ICAM3-grabbing non-integrin.,[8] CD209 ,[9] Rab 5 ,[10] GRP 78 ,[11] and The Mannose Receptor [12])have been shown to be important factors mediating attachment and viral entry.[13]

prM/M protein

The DENV prM (membrane) protein, which is important in the formation and maturation of the viral particle, consists of seven antiparallel β-strands stabilized by three disulphide bonds.[13]

The glycoprotein shell of the mature DENV virion consists of 180 copies each of the E protein and M protein. The immature virion starts out with the E and prM proteins forming 90 heterodimers that give a spiky exterior to the viral particle. This immature viral particle buds into the endoplasmic reticulum and eventually travels via the secretory pathway to the golgi apparatus. As the virion passes through the trans-Golgi Network (TGN) it is exposed to low pH. This acidic environment causes a conformational change in the E protein which disassociates it from the prM protein and causes it to form E homodimers. These homodimers lay flat against the viral surface giving the maturing virion a smooth appearance. During this maturation pr peptide is cleaved from the M peptide by the host protease, furin. The M protein then acts as a transmembrane protein under the E-protein shell of the mature virion. The pr peptide stays associated with the E protein until the viral particle is released into the extracellular environment. This pr peptide acts like a cap, covering the hydrophobic fusion loop of the E protein until the viral particle has exited the cell.[13]

NS3 protein

The DENV NS3 is a serine protease, as well as an RNA helicase and RTPase/NTPase. The protease domain consists of six β-strands arranged into two β-barrels formed by residues 1-180 of the protein. The catalytic triad (His-51, Asp-75 and Ser-135), is found between these two β-barrels, and its activity is dependent on the presence of the NS2B cofactor. This cofactor wraps around the NS3 protease domain and becomes part of the active site. The remaining NS3 residues (180-618), form the three subdomains of the DENV helicase. A six-stranded parallel β-sheet surrounded by four α-helices make up subdomains I and II, and subdomain III is composed of 4 α-helices surrounded by three shorter α-helices and two antiparallel β-strands.[13]

NS5 protein

The DENV NS5 protein is a 900 residue peptide with a methyltransferase domain at its N-terminal end (residues 1-296) and a RNA-dependent RNA polymerase (RdRp) at its C-terminal end (residues 320–900). The methyltransferase domain consists of an α/β/β sandwich flanked by N-and C-terminal subdomains. The DENV RdRp is similar to other RdRps containing palm, finger, and thumb subdomains and a GDD motif for incorporating nucleotides.[13]

The reason that some people suffer from more severe forms of dengue, such as dengue hemorrhagic fever, is multifactorial. Different strains of viruses interacting with people with different immune backgrounds lead to a complex interaction. Among the possible causes are cross-serotypic immune response, through a mechanism known as antibody-dependent enhancement, which happens when a person who has been previously infected with dengue gets infected for the second, third or fourth time. The previous antibodies to the old strain of dengue virus now interfere with the immune response to the current strain, leading paradoxically to more virus entry and uptake. [14]

Diagnosis

The diagnosis of dengue is often made clinically. The classic picture is high fever of sudden onset with no localising source of infection, a rash with thrombocytopenia and relative leukopenia - low platelet and white blood cell count. Dengue infection can affect many organs and thus may present unusually as liver dysfunction, renal impairment, meningo-encephalitis or gastroenteritis.

The World Health Organization propose in 1997 [15] that anyone with an acute history of fever, living in an endemic region or having a positive dengue test by serology and with two or more of the following symptoms was likely to have dengue:

- Headache

- Arthralgia

- Myalgia

- Retro-orbital pain

- Leucopenia (low white cell count)

- Rash

- Haemorrhagic manifestations

Alternatively laboratory confirmation of dengue fever required

- isolation of the virus from clinical samples

- four-fold increase in antibody titres to the virus in paired serum samples

- demonstration of viral antigen in clinical samples

- detection of virus genome in clinical samples

The diagnosis of the more severe dengue haemorrhagic fever (DHF) syndrome required four features to be present:

- Fever

- Hemorrhagic tendency (positive tourniquet test, spontaneous bruising, bleeding from mucosa, gingiva, injection sites, etc.; vomiting blood, or bloody diarrhea)

- Thrombocytopenia (<100,000 platelets per mm³ or estimated as less than 3 platelets per high power field)

- Evidence of plasma leakage (hematocrit more than 20% higher than expected, or drop in hematocrit of 20% or more from baseline following IV fluid, pleural effusion, ascites, hypoproteinemia)

Dengue shock syndrome is defined as dengue hemorrhagic fever plus either:

- Weak rapid pulse and narrow pulse pressure (less than 20 mm Hg); or

- Hypotension for age and cold, clammy skin and restlessness.

Rapid Diagnostic Test (RDT) kits, can provide useful diagnostic information especially in the field, e.g. in rural areas without full laboratory facilities. Such a diagnostic kit may consist of a "test cassette" or other device. One type is described as follows: "Dengue fever rapid test devices, also known as one-step dengue tests, are a solid phase immuno-chromatographic assay for the rapid, qualitative and differential detection of dengue IgG and IgM antibodies to dengue fever virus in human serum, plasma or whole blood." Atlas Link Biotech co. Ltd (2008)Dengue Fever Rapid Test Kits. Accessed: 27/06/09. Available at: http://www.ivdpretest.com/Dengue-Rapid-Tests.html</ref> Serology and polymerase chain reaction (PCR) studies are available to confirm the diagnosis of dengue if clinically indicated.

One test is called Platelia Dengue NS1 Ag assay, or NS1 antigen test for short, made by Bio-Rad Laboratories and Pasteur Institute, introduced in 2006, allows rapid detection before antibodies appear the first day of fever.[16][17]

The definitive serological diagnosis of dengue requires two blood samples taken at least 4-7 days apart. Rapid definitive testing involves either detection of viral genome using PCR or detection of viral antigen, usually non-structural protein 1 (NS1). An example of the impact of rapid testing was the implemention in September 2010 in India which cut short the waiting time to 48 hours. This may be associated with a higher cost (approximately 1,600 rupees).[18]

In many poverty stricken areas, definitive diagnosis may be too expensive and/or meaningless (given there is no cure, only supportive therapy) so significant under-reporting is expected to be the norm.

Prevention

There is no tested and approved vaccine for the dengue flavivirus. There are many ongoing vaccine development programs. Among them is the Pediatric Dengue Vaccine Initiative set up in 2003 with the aim of accelerating the development and introduction of dengue vaccine(s) that are affordable and accessible to poor children in endemic countries.[19] Thai researchers are testing a dengue fever vaccine on 3,000–5,000 human volunteers after having successfully conducted tests on animals and a small group of human volunteers.[20] A number of other vaccine candidates are entering phase I or II testing.[21] As of July 2010, the National Institutes of Health reported on their ClinicalTrials.Gov Web site that there were 11 vaccines undergoing testing or recruiting for participants.[22] Because exposure to one of dengue's four serotypes provides no immunity against infection by the other types, and may make the patient susceptible to more severe disease symptoms, testing vaccines must be performed carefully, and usually not in areas where the disease is endemic for fear that even attenuated virus vaccines may cause severe reactions.[23]

In 1998, scientists from the Queensland Institute of Medical Research (QIMR) in Australia and Vietnam's Ministry of Health introduced a scheme that encouraged children to place a water bug, the crustacean Mesocyclops, in water tanks and discarded containers where the Aedes aegypti mosquito was known to thrive.[24] This method is viewed as being more cost-effective and more environmentally friendly than pesticides, though not as effective, and requires the continuing participation of the community.[25]

Even though this method of mosquito control was successful in rural provinces, not much is known about how effective it could be if applied to cities and urban areas. The Mesocyclops can survive and breed in large water containers but would not be able to do so in small containers that most urban dwellers have in their homes. Also, Mesocyclops are hosts for the guinea worm, a pathogen that causes a parasite infection, and so this method of mosquito control cannot be used in countries that are still susceptible to the guinea worm. The biggest dilemma with Mesocyclops is that its success depends on the participation of the community. This idea of a possible parasite-bearing creature in household water containers dissuades people from continuing the process of inoculation and, without the support and work of everyone living in the city, this method will not be successful.[26]

Treatment

The mainstay of treatment is timely supportive therapy to tackle circulatory shock due to hemoconcentration and bleeding. Close monitoring of vital signs in the critical period (up to 2 days after defervescence - the departure or subsiding of a fever) is critical. Oral rehydration therapy is recommended to prevent dehydration in moderate to severe cases. Supplementation with intravenous fluids may be necessary to prevent dehydration and significant concentration of the blood if the patient is unable to maintain oral intake. A platelet transfusion may be indicated if there is significant bleeding. The presence of melena may indicate internal gastrointestinal bleeding requiring platelet and/or red blood cell transfusion.

Aspirin and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs should be avoided as these drugs may worsen the bleeding tendency associated with some of these infections. All kinds of intramuscular injections are contraindicated in patients with low platelets. Patients may receive paracetamol (acetaminophen) preparations to deal with these symptoms if dengue is suspected.[27]

Epidemiology

Dengue is transmitted by Aedes mosquitoes, particularly A. aegypti and A. albopictus. Though primarily transmitted between humans and often asymptomatically, sylvatic (forest) strains of dengue are known which are presumably transmitted through a cycle involving wild animals. Some evidence of dengue virus in a variety of wild mammals has recently been shown in the Americas and in China. These sylvatic strains occasionally infect humans. It is unknown if human strains circulate widely in wild animals.

The first recognized Dengue epidemics occurred almost simultaneously in Asia, Africa, and North America in the 1780s, shortly after the identification and naming of the disease in 1779. A pandemic began in Southeast Asia in the 1950s, and by 1975 DHF had become a leading cause of death among children in the region. Epidemic dengue has become more common since the 1980s. By the late 1990s, dengue was the most important mosquito-borne disease affecting humans after malaria, with around 40 million cases of dengue fever and several hundred thousand cases of dengue hemorrhagic fever each year. Significant outbreaks of dengue fever tend to occur every five or six months. The cyclical rise and fall in numbers of dengue cases is thought to be the result of seasonal cycles interacting with a short-lived cross-immunity[clarification needed] for all four strains in people who have had dengue. When the cross-immunity wears off the population is more susceptible to transmission whenever the next seasonal peak occurs. Thus over time there remain large numbers of susceptible people in affected populations despite previous outbreaks due to the four different serotypes of dengue virus and the presence of unexposed individuals from childbirth or immigration.

There is significant evidence, originally suggested by S.B. Halstead in the 1970s, that dengue hemorrhagic fever is more likely to occur in patients who have secondary infections by another one of dengue fever's four serotypes. One model to explain this process is known as antibody-dependent enhancement (ADE), which allows for increased uptake and virion replication during a secondary infection with a different strain. Through an immunological phenomenon, known as original antigenic sin, the immune system is not able to adequately respond to the stronger infection, and the secondary infection becomes far more serious.[28]

Reported cases of dengue are an under-representation of all cases when accounting for subclinical cases and cases where the patient did receive medical treatment.

There was a serious outbreak in Rio de Janeiro in February 2002 affecting around one million people and killing sixteen. On March 20, 2008, the secretary of health of the state of Rio de Janeiro, Sérgio Côrtes, announced that 23,555 cases of dengue, including 30 deaths, had been recorded in the state in less than three months. Côrtes said, "I am treating this as an epidemic because the number of cases is extremely high." Federal Minister of Health, José Gomes Temporão also announced that he was forming a panel to respond to the situation. Cesar Maia, mayor of the city of Rio de Janeiro, denied that there was serious cause for concern, saying that the incidence of cases was in fact declining from a peak at the beginning of February.[29] By April 3, 2008, the number of cases reported rose to 55,000 [30]

In Singapore, there are 4,000–5,000 reported cases of dengue fever or dengue haemorrhagic fever every year. In the year 2004, there were seven deaths from dengue shock syndrome.[31]

It occurs widely in the tropics, including the Southern United States,[32] northern Argentina, northern Australia, Bangladesh, Barbados, Bolivia,[33] Belize, Brazil, Cambodia, Colombia, Costa Rica, Cuba, Dominican Republic, French Polynesia, Guadeloupe, El Salvador, Grenada, Guatemala, Guyana, Haiti, Honduras, India, Indonesia, Jamaica, Laos, Malaysia, Melanesia, Mexico, Micronesia, Nicaragua, Pakistan, Panama, Paraguay,[34] The Philippines, Puerto Rico, Samoa,[35] Western Saudi Arabia, Singapore, Sri Lanka, Suriname, Taiwan, Thailand, Trinidad and Tobago, Venezuela and Vietnam, and increasingly in southern China.[36]

Recent outbreaks

There is an ongoing 2010 outbreak occurring in Puerto Rico with 5382 confirmed infections and 20 deaths. Nearby Guadeloupe and Martinique, in the French Caribbean, were very much affected as well: over 40000 clinical cases in each island required medical assistance (the outbreak peaked in August 2010 and was practically over by October). [37] [38].There is also an ongoing outbreak occurring in Pakistan with more than 5000 confirmed infections and death toll rose to 31. The 2010 and 2009 dengue outbreaks in Key West Florida [39][40] are similar to the 2005 Texas (25 cases) and 2001 Hawaii (122 cases) outbreaks, which were locally sustained on American soil and not a result of travelers returning from endemic areas.[41]

American visitors to and visitors from dengue-endemic regions will continue to present a potential pathway for the dengue virus to enter the United States and infect populations that have not been exposed to the virus for several decades.[41][42] The health risks and rapidly escalating costs to the United States of unmonitored, unvaccinated and disease carrying travelers, legal and illegal, has been recently considered.[41][43]

An outbreak of dengue fever was declared in Cairns, located in the tropical north of Queensland, Australia on 1 December 2008. As of 3 March 2009 there were 503 confirmed cases of dengue fever, in a residential population of 152,137. Outbreaks were subsequently declared the neighbouring cities and towns of Townsville (outbreak declared 5 January 2009), Port Douglas (6 February 2009), Yarrabah (19 February 2009), Injinoo (24 February 2009), Innisfail (27 February 2009) and Rockhampton (10 March 2009). There have been occurrences of dengue types one, two, three, and four in the region. On March 4, 2009, Queensland Health had confirmed an elderly woman had died from dengue fever in Cairns, in the first fatality since the epidemic began last year. The statement said that although the woman had other health problems, she tested positive for dengue and the disease probably contributed to her death.

An epidemic broke out in Bolivia in early 2009, in which 18 people have died and 31,000 infected.

In 2009, in Argentina, a dengue outbreak was declared the northern provinces of Chaco, Catamarca, Salta, Jujuy, and Corrientes, with over 9673 cases reported as of April 11, 2009 by the Health Ministry [10]. Some travelers from the affected zones have spread the fever as far south as Buenos Aires [11]. Major efforts to control the epidemic in Argentina are focused on preventing its vector (the Aedes mosquitoes) from reproducing. This is addressed by asking people to dry out all possible water reservoirs from where mosquitoes could proliferate (which is, in other countries, known as "descacharrado"). There have also been information campaigns concerning prevention of the dengue fever; and the government is fumigating with insecticide in order to control the mosquito population.[44]

The first cases of dengue fever have recently been reported on the island nation of Mauritius in the Indian Ocean. One of the South Asian countries still suffering highly from this problem is Sri Lanka.[45]

Dengue fever also claimed the life in 2010 of renowned surfer Andy Irons. (Although recent reports have indicated that his death may have been caused by a drug overdose). [12]

2010 Outbreak table

Of the countries in the table below, the only nations with lower cases and deaths so far in 2010 are Singapore, Mexico, Guadeloupe and the United States. In many undeveloped regions, including parts of India, "authorities do not have adequate facilities to detect dengue cases."[46] Notably, in the Philippines where patients seek herbal medication in lieu of hospitals for treating dengue, death rates as evidenced below are statistically far greater than other affected areas. As many cases go unreported, higher statistics here do not necessarily indicate a larger outbreak.

| Country | Region | Confirmed Cases Dengue (This year) |

Suspected Cases (This year) |

Reported Deaths (This year) |

Compared with previous year | Figures as of** |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| World (sum of all regions) | 1,689,737 | N.A. | 2,270 | |||

| - | 936,000 | - | 592 | 489,819 | mid Oct[47] | |

| - | 121,600 | - | 161 | - | Sep 24[48] | |

| - | - | N/A | N/A | 155,000 and 1386 deaths[49] | no date | |

| - | 119,789 | - | 724 | 49,319 (up 140%) | Nov 17[50] | |

| - | 104,041 | - | - | 42,466 (up 144.9%) | week 42[51] | |

| - | 86,407 | - | 100 | up 134.7% | Sep 27[52] | |

| - | ~80,000 | - | 59 | 105,370 (whole year) | Sep [53] | |

| - | 62,576 | - | 74 | 12,824[54] | Week 38[55] | |

| - | 40,959 | - | 119 | up 19% | oct 30[56] | |

| - | 26,824 | - | 192 | mid Jul[57] | ||

| - | 21,000 | - | N/A | 3,326 | end Aug[58] | |

| - | 14,659 | - | 39 | 7,214(whole year) | aug 28[59] | |

| - | 13,990 | - | 22 | - | Sep 18[60] | |

| - | 13,678 | 6138 | n/a | n/a | sep 30[61] | |

| - | 12,240 | - | 20 | 15,032 | week 32 (sep)[62] | |

| - | 8,839 | - | 41 | 3,000 | Sep 3[63] | |

| - | 6,458 | 15,068 | 1 | n/a | week 28[64] | |

| Delhi | 5,837 | - | 8 | 1,153 | Nov 9 [65] | |

| - | 7,000+ | - | 35 | - | Nov 22[66] | |

| - | 2,608 | - | 41 | 3,050 | end aug[67] | |

| Martinique | 644 | 41970 | 17 | Nov 22 [68] | ||

| Guadeloupe | 418 | 44000 | 5 | Nov 22 [69] | ||

| - | 1,925 | 11,800 | 25 | 1 sep[70] | ||

| Yogyakarta | 1123 | - | - | 688 (whole year) | Sep 26[71] | |

| - | 1211 | - | 2 | 1052 | Nov 1[72] | |

| - | 1,200 | - | 4 | N/A | end aug[73] | |

| Uttar Pradesh | 496 | - | 8 | Oct 20[74] | ||

| Chitwan | 280 | - | - | - | Oct 17, 2010[75] | |

| - | 198 (24-2010FL, 27-2009FL, 25-2005TX, 122-2001HI) [40][41][76] | 2 (2010, suspected)[77] [78] | Cases down 11% from 2009[76] | Aug 3, 2010 [79] | ||

| Mayotte | 75 | - | N/A | Sep 1[63] | ||

| Queensland | 13 | 0 | 1 | Nov 3, 2010[80] |

Blood transfusion

Dengue may also be transmitted via infected blood products (blood transfusions, plasma, and platelets),[81][82] and in countries such as Singapore, where dengue is endemic, the risk was estimated to be between 1.6 and 6 per 10,000 blood transfusions.[83]

History

Etymology

The origins of the word dengue are not clear, but one theory is that it is derived from the Swahili phrase "Ka-dinga pepo", which describes the disease as being caused by an evil spirit.[84] The Swahili word "dinga" may possibly have its origin in the Spanish word "dengue" meaning fastidious or careful, which would describe the gait of a person suffering the bone pain of dengue fever.[85] Alternatively, the use of the Spanish word may derive from the similar-sounding Swahili.[86]

Literature

Slaves in the West Indies who contracted dengue were said to have the posture and gait of a dandy, and the disease was known as "Dandy Fever".[87] The first record of a case of probable dengue fever is in a Chinese medical encyclopedia from the Jin Dynasty (265–420 AD) which referred to a “water poison” associated with flying insects.[86] The first confirmed case report dates from 1789 and is by Benjamin Rush, who coined the term "breakbone fever" because of the symptoms of myalgia and arthralgia.[88] The viral etiology and the transmission by mosquitoes were discovered in the 20th century by Sir John Burton Cleland.

Population movements during World War II spread the disease globally. A pandemic of dengue began in Southeast Asia after World War II and has spread around the globe since then.[89]

Society and culture

Use as a biological weapon

Dengue fever was one of more than a dozen agents that the United States researched as potential biological weapons before the nation suspended its biological weapons program.[90]

Research

Emerging evidence suggests that mycophenolic acid and ribavirin inhibit dengue replication. Initial experiments showed a fivefold increase in defective viral RNA production by cells treated with each drug.[91] In vivo studies, however, have not yet been done. Unlike HIV therapy, lack of adequate global interest and funding greatly hampers the development of a treatment regime.

Management

Singapore has managed to reduce the cases of not only dengue, but chikungunya and malaria by introducing an Integrated Vector Management System. Cases fell from 7,500 to 4,500 in 2008,[92] the 2,608 cases reported so far this year up until August 19, represent a lower rate than preceeding years.[67] For chikungunya, the results are dramatic, cases fell from 720 in 2008 to only 22 cases this year so far.[92]

Wolbachia

In 2009, scientists from the School of Integrative Biology at The University of Queensland revealed that by infecting Aedes mosquitos with the bacterium Wolbachia, the adult lifespan was reduced by half.[93] In the study, super-fine needles were used to inject 10,000 mosquito embryos with the bacterium. Once an insect was infected, the bacterium would spread via its eggs to the next generation. A pilot release of infected mosquitoes could begin in Vietnam within three years. If no problems are discovered, a full-scale biological attack against the insects could be launched within five years.[94]

Antiviral approaches

Dengue virus belongs to the family Flaviviridae, which includes the hepatitis C virus, West Nile and Yellow fever viruses among others. Possible laboratory modification of the yellow fever vaccine YF-17D to target the dengue virus via chimeric replacement has been discussed extensively in scientific literature,[95] but as of 2009[update] no full scale studies have been conducted.[96]

In 2006 a group of Argentine scientists discovered the molecular replication mechanism of the virus, which could be specifically attacked by disrupting the viral RNA polymerase.[97] In cell culture[98] and murine experiments[99][100] morpholino antisense oligomers have shown specific activity against Dengue virus.

Sterile insect technique

The sterile insect technique, a form of biological control, has long proved difficult with mosquitos because of the fragility of the males.[101] However, a transgenic strain of Aedes aegypti was announced in 2010 which might alleviate this problem: the strain produces females that are flightless due to a mis-development of their wings,[102] and so can neither mate nor bite. The genetic defect only causes effects in females, so that males can act as silent carriers.[101]

See also

- Discovering Dengue Drugs – Together, a distributed computing project attempting to identify drug leads with broad spectrum activity against dengue.

References

- ^ "Chapter 4, Prevention of Specific Infectious Diseases". CDC Traveler's Health: Yellow Book. Retrieved 2007-05-20.

- ^ "Travelers' Health Outbreak Notice". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. June 2, 2010. Retrieved 2010-09-03.

- ^ Dengue epidemic threatens India's capital

- ^ Ryan KJ, Ray CG (editors) (2004). Sherris Medical Microbiology (4th ed.). McGraw Hill. p. 592. ISBN 0838585299.

{{cite book}}:|author=has generic name (help) - ^ http://nvbdcp.gov.in/Doc/guidelines%20for%20treatment%20of%20Dengue.pdf

- ^ http://www.neurologyindia.com/article.asp?issn=0028-3886;year=2010;volume=58;issue=4;spage=585;epage=591;aulast=Varatharaj

- ^ Hanley, K.A. and Weaver, S.C. (editors) (2010). Frontiers in Dengue Virus Research. Caister Academic Press. ISBN 978-1-904455-50-9.

{{cite book}}:|author=has generic name (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ ,Tassaneetrithep, B et al. DC-SIGN (CD209) mediates dengue virus infection of human dendritic cells. J Exp Med 2003;197:823–829.

- ^ ,Krishnan, MN et al. Rab 5 is required for the cellular entry of dengue and West Nile viruses. J Virol 2007;81:4881–4885.

- ^ ,Jindadamrongwech, S et al. Identification of GRP 78 (BiP) as a liver cell expressed receptor element for dengue virus serotype 2. Arch Virol 2004;149:915–927.

- ^ , Miller, JL et al. The Mannose Receptor Mediates Dengue Virus Infection of Macrophages. PLoS Pathog 2008;4:e17.

- ^ a b c d e ,Perera, Rushika and Kuhn, Richard J. Structural Proteomics of Dengue Virus. Curr Opin Microbiol. 2008 August ; 11(4): 369–377.

- ^ Attention: This template ({{cite doi}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by doi:10.1126/science.1185181, please use {{cite journal}} (if it was published in a bona fide academic journal, otherwise {{cite report}} with

|doi=10.1126/science.1185181instead. - ^ "Chapter 2, Clinical Diagnosis in Dengue haemorrhagic fever: diagnosis, treatment, prevention and control. 2nd edition" (PDF). World Health Organization.

- ^ http://www.selectscience.net/product-news/bio-rad-laboratories-informatics-division/bio-rad-launches-test-for-early-diagnosis-of-the-dengue-virus/?artID=9997

- ^ http://www.mymedicnews.com/story/2010-jan-08-18/dengue-ns1-antigen-new-paradigm-early-dengue-detection

- ^ "Now, get dengue test results in just 48 hours". The Times Of India. 2010-09-16.

- ^ "Pediatric Dengue Vaccine Initiative". 2008. Retrieved 2008-10-05.

- ^ "Thailand to test Mahidol-developed dengue vaccine prototype". People's Daily Online. 2005-09-05. Retrieved 2006-10-08.

- ^ Edelman R (2007). "Dengue vaccines approach the finish line". Clinical infectious diseases : an official publication of the Infectious Diseases Society of America. 45 Suppl 1: S56–60. doi:10.1086/518148. PMID 17582571.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ [1]

- ^ [2]

- ^ Vu SN, Nguyen TY, Kay BH, Marten GG, Reid JW (1 October 1998). "Eradication of Aedes aegypti from a village in Vietnam, using copepods and community participation". Am J Trop Med Hyg. 59 (4): 657–60. PMID 9790448.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "Water bug aids dengue fever fight". BBC News. 2005-02-11. Retrieved 2008-10-05.

Kay B, Vu SN (2005). "New strategy against Aedes aegypti in Vietnam". Lancet. 365 (9459): 613–7. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(05)17913-6. PMID 15708107. - ^ "Control of aedes vectors of dengue in three provinces of Vietnam by use of Mesocyclops (Copepoda) and community-based methods validated by entomologic, clinical, and serological surveillance". The American Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene. 2002. Retrieved 2009-02-18.

- ^ "Dengue & DHF: Information for Health Care Practitioners". Dengue Fever. CDC Division of Vector-Borne Infectious Diseases (DVBID). 2007-10-22. Retrieved 2008-10-05.

- ^ Rothman AL (2004). "Dengue: defining protective versus pathologic immunity". J. Clin. Invest. 113 (7): 946–51. doi:10.1172/JCI200421512. PMC 379334. PMID 15057297.

- ^ Fernanda Pontes (20 March 2008). "Secretário estadual de Saúde Sérgio Côrtes admite que estado vive epidemia de dengue". O Globo Online (in Portuguese)..

- ^ CNN (3 April 2008). "Thousands hit by Brazil outbreak of dengue". CNN.

{{cite news}}:|author=has generic name (help) - ^ http://www.sciencedirect.com/science?_ob=ArticleURL&_udi=B7CPT-4KKNNH5-2&_user=130561&_rdoc=1&_fmt=&_orig=search&_sort=d&view=c&_acct=C000010878&_version=1&_urlVersion=0&_userid=130561&md5=4cc1b9743b4fddf5a0567b16b99bc130

- ^ http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/mm5919a1.htm

- ^ Schipani, Andres (2009-02-03). "Dengue fever outbreak in Bolivia". BBC. Retrieved 2009-02-26.

- ^ Reuters, "Dengue Fever Hits Paraguay", New York Times" (March 4, 2007)

- ^ http://www.samoalivenews.com/Health/Dengue-Fever-Outbreak-Confirmed-In-Samoa.html

- ^ "Zhuhai reports outbreak of dengue fever". China Daily. 200-09-06. Retrieved 2009-11-18.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ "INVS Bulletin" (PDF).

{{cite news}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|1=(help) - ^ http://www.invs.sante.fr/surveillance/dengue/points_martinique/2010/pe_martinique_2010_26_dengue.pdf

- ^ Maugh II, Thomas H. (2010-07-14). "Dengue fever outbreak feared in Key West [Updated]". Los Angeles Times.

- ^ a b [3]

- ^ a b c d [4]

- ^ [5]

- ^ [6]

- ^ Marcos Wozniak (12 March 2009).

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help); Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ Sri Lanka

- ^ http://ibnlive.in.com/generalnewsfeed/news/11-die-due-to-viral-malaria-and-dengue-fever-in-kanpur/336489.html

- ^ http://vaccinenewsdaily.com/news/220671-dengue-fever-deaths-on-the-rise-in-brazil

- ^ http://www.elheraldo.com.co/ELHERALDO/BancoConocimiento/0/0van_127600_casos_de_dengue/0van_127600_casos_de_dengue.asp?CodSeccion=25

- ^ http://www.lintasberita.com/Nasional/Berita-Lokal/cme-fk-uii-2010-kaji-virus-dengue

- ^ http://www.monstersandcritics.com/news/health/news/article_1599851.php/Death-toll-from-dengue-fever-hits-724-in-the-Philippines

- ^ http://www.entornointeligente.com/resumen/resumen.php?items=1072882

- ^ http://www.ryt9.com/s/iq01/993388

- ^ http://www.saigon-gpdaily.com.vn/Health/2010/9/85697/

- ^ http://www.elnuevoherald.com/2010/09/18/804653/aumentan-a-68-los-muertos-por.html

- ^ http://www.elheraldo.hn/Ediciones/2010/10/02/Noticias/Certifican-dos-muertes-por-dengue-en-Honduras

- ^ http://thestar.com.my/news/story.asp?file=/2010/11/4/nation/20101104191018&sec=nation

- ^ http://pacific.scoop.co.nz/2010/09/sri-lanka-dengues-human-cost/

- ^ http://www.insidecostarica.com/dailynews/2010/september/03/costarica10090304.htm

- ^ http://www.asianewsnet.net/news.php?id=14480&sec=22

- ^ http://www.elnuevodia.com/dengueentrelapreocupacionyladejadez-782462.html

- ^ http://www.diariovanguardia.com.py/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=2562:existe-corte-de-circulacion-viral-en-el-66-de-regiones-sanitarias&catid=56:salud&Itemid=413

- ^ http://www.dgepi.salud.gob.mx/denguepano/dengue-2010.html

- ^ a b http://www.promedmail.org/pls/otn/f?p=2400:1001:2447503484227822::NO::F2400_P1001_BACK_PAGE,F2400_P1001_PUB_MAIL_ID:1000,84660

- ^ http://migenteinforma.org/el-dengue-prolifera-en-las-fronteras-de-guatemala-honduras-y-el-salvador

- ^ "35 new dengue cases in Delhi". The Times Of India.

- ^ http://www.dailytimes.com.pk/default.asp?page=2010\11\01\story_1-11-2010_pg1_5

- ^ a b http://wildsingaporenews.blogspot.com/2010/08/surge-in-dengue-cases-in-singapore.html

- ^ http://www.invs.sante.fr/surveillance/dengue/points_martinique/2010/pe_martinique_2010_26_dengue.pdf

- ^ http://www.invs.sante.fr/surveillance/dengue/points_guadeloupe/2010/pep_guadeloupe_2010_28_dengue.pdf

- ^ http://spanish.peopledaily.com.cn/31614/7133542.html

- ^ http://www.republika.co.id/berita/breaking-news/kesehatan/10/09/21/135726-hujan-terus-kasus-dbd-di-yogya-naik-40-persen

- ^ http://nidss.cdc.gov.tw/SingleDisease.aspx?Pt=s&dc=1&dt=2&disease=061

- ^ http://www.etaiwannews.com/etn/news_content.php?id=1365772&lang=eng_news

- ^ http://www.expressindia.com/latest-news/mystery-fever-health-officials-differ-on-toll/700438/

- ^ http://www.thehimalayantimes.com/fullNews.php?headline=Lawmakers+continue+surveying+dengue-hit+areas+&NewsID=261673

- ^ a b [7]

- ^ [8]

- ^ [9]

- ^ "Florida confirms 24 cases of dengue fever in Key West". CNN. 2010-08-04.

- ^ http://www.abc.net.au/news/stories/2010/10/15/3039601.htm

- ^ Wilder-Smith A, Chen LH, Massad E, Wilson ME (2009). "Threat of dengue to blood safety in dengue-endemic countries". Emerg Infect Dis. 15 (1): 8–11. doi:10.3201/eid1501.071097. PMC 2660677. PMID 19116042.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Stramer SL, Hollinger FB, Katz LM, Kleinman S, Metzel PS, Gregory KR, Dodd RY (2009). "Emerging infectious disease agents and their potential threat to transfusion safety". Transfusion. 49 (Suppl 2): 1–29. doi:10.1111/j.1537-2995.2008.02019.x. PMID 19686562.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Teo D, Ng LC, Lam S (2009). "Is dengue a threat to the blood supply?". Transfus Med. 19 (2): 66–77. doi:10.1111/j.1365-3148.2009.00916.x. PMC 2713854. PMID 19392949.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "Dengue fever: essential data". 1999. Retrieved 2008-10-05.

- ^ Harper D (2001). "Etymology: dengue". Online Etymology Dictionary. Retrieved 2008-10-05.

- ^ a b "etymologia: dengue" (PDF). Emerging Infectious Diseases. 12 (6): 893. 2006.

- ^ url=http://www.medterms.com/script/main/art.asp?articlekey=6620

- ^ Gubler DJ (1998). "Dengue and dengue hemorrhagic fever". Clinical microbiology reviews. 11 (3): 480–96. PMC 88892. PMID 9665979.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Dengue Fever Fact Sheet. CDC.

- ^ "Chemical and Biological Weapons: Possession and Programs Past and Present", James Martin Center for Nonproliferation Studies, Middlebury College, April 9, 2002, accessed November 14, 2008.

- ^ Takhampunya R, Ubol S, Houng HS, Cameron CE, Padmanabhan R (2006). "Inhibition of dengue virus replication by mycophenolic acid and ribavirin". J. Gen. Virol. 87 (Pt 7): 1947–52. doi:10.1099/vir.0.81655-0. PMID 16760396.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b http://www.channelnewsasia.com/stories/singaporelocalnews/view/1078250/1/.html

- ^ McMeniman CJ, Lane RV, Cass BN; et al. (2009). "Stable Introduction of a Life-Shortening Wolbachia Infection into the Mosquito Aedes aegypti". Science. 323 (5910): 141–4. doi:10.1126/science.1165326. PMID 19119237.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "Dengue fever breakthrough". Sydney Morning Herald. 2009-01-02. Retrieved 2009-01-02.

- ^ Lai CJ, Monath TP (2003). "Chimeric flaviviruses: novel vaccines against dengue fever, tick-borne encephalitis, and Japanese encephalitis". Advances in virus research. 61: 469–509. doi:10.1016/S0065-3527(03)61013-4. PMID 14714441.

- ^ Querec T, Bennouna; Bennouna, S; Alkan, S; Laouar, Y; Gorden, K; Flavell, R; Akira, S; Ahmed, R; Pulendran, B (2006). "Yellow fever vaccine YF-17D activates multiple dendritic cell subsets via TLR2, 7, 8, and 9 to stimulate polyvalent immunity". J. Exp. Med. 203 (2): 413–24. doi:10.1084/jem.20051720. PMC 2118210. PMID 16461338.

- ^ Filomatori CV, Lodeiro MF, Alvarez DE, Samsa MM, Pietrasanta L, Gamarnik AV (2006). "A 5' RNA element promotes dengue virus RNA synthesis on a circular genome". Genes Dev. 20 (16): 2238–49. doi:10.1101/gad.1444206. PMC 1553207. PMID 16882970.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Kinney RM, Huang CY, Rose BC; et al. (2005). "Inhibition of dengue virus serotypes 1 to 4 in vero cell cultures with morpholino oligomers". Journal of virology. 79 (8): 5116–28. doi:10.1128/JVI.79.8.5116-5128.2005. PMC 1069583. PMID 15795296.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Burrer R, Neuman BW, Ting JP; et al. (2007). "Antiviral effects of antisense morpholino oligomers in murine coronavirus infection models". Journal of virology. 81 (11): 5637–48. doi:10.1128/JVI.02360-06. PMC 1900280. PMID 17344287.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Stein DA, Huang CY, Silengo S; et al. (2008). "Treatment of AG129 mice with antisense morpholino oligomers increases survival time following challenge with dengue 2 virus". The Journal of antimicrobial chemotherapy. 62 (3): 555–65. doi:10.1093/jac/dkn221. PMID 18567576.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Fua, Guoliang; Leesa, Rosemary S.; Nimmoa, Derric; Awc, Diane; Jina, Li; Graya, Pam; Berendonkb, Thomas U.; White-Cooperb, Helen; Scaifea, Sarah (2010). "Female-specific flightless phenotype for mosquito control" (PDF). Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 107 (10): 4550. doi:10.1073/pnas.1000251107. PMC 2826341. PMID 20176967..

- ^ 'Lame' mosquitoes to stop dengue. BBC News. 23 February 2010..

External links

- Dengue fever at Curlie

- Dengue Virus Genomes database search results from the Dengue Virus Database at the Viral Bioinformatics Resource Center

- "Discovering Dengue Drugs – Together". University of Texas Medical Branch. 2009-01-04. Retrieved 2009-01-04.

- Dengue Fever Alliance - Todos Frente al Dengue Alliance to strengthen the capacity of action and management for A World Free of Dengue Fever

- Dengue: CDC home page The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC)

- Dengue: Clinical and Public Health Aspects, The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC)

- Dengue haemorrhagic fever: diagnosis, treatment, prevention and control 2nd edition. Geneva : World Health Organization.

- The NCBI Virus Variation Resources The Virus Variation Resources at The National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI).

- Dengue Virus Net Information site for dengue symptoms, prevention, treatment, vaccine research and outbreak news.

- Virus Pathogen Database and Analysis Resource (ViPR): Flaviviridae