Pharaoh: Difference between revisions

Saddhiyama (talk | contribs) Reverted good faith edits by PretoriaTravel (talk): We have countless contemporary depictions. this seems a bit WP:UNDUE. (TW) |

|||

| Line 83: | Line 83: | ||

==See also== |

==See also== |

||

*[[Egyptian chronology]] - [[Conventional Egyptian chronology]] |

*[[Egyptian chronology]] - [[Conventional Egyptian chronology]] |

||

| ⚫ | |||

*[[History of Egypt]] |

*[[History of Egypt]] |

||

| ⚫ | |||

*[[List of Pharaohs]] |

*[[List of Pharaohs]] |

||

*[[Monarch]] |

*[[Monarch]] |

||

*[[Pharaoh of the Exodus]] |

*[[Pharaoh of the Exodus]] |

||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | |||

==References== |

==References== |

||

Revision as of 21:01, 23 January 2013

| ||||||||||||||

| nesu-bit "King of Upper and Lower Egypt" in hieroglyphs | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Pharaoh (/[invalid input: 'icon']ˈfeɪ.roʊ/, /fɛr.oʊ/[1][2] or /fær.oʊ/[2]) is a title used in many modern discussions of the rulers of all Ancient Egyptian dynasties.[3] The title originates in the term "pr-aa" which means "great house" and it describes the royal palace. Historically, however, pharaoh only started being used as a title for the king during the New Kingdom, specifically during the middle of the eighteenth dynasty, after the reign of Hatshepsut.[4]

History of the title

Pharaoh, meaning "Great House", originally referred to the king's palace, but during the reign of Thutmose III (ca. 1479-1425 BCE) in the New Kingdom, after the foreign rule of the Hyksos during the Second Intermediate Period, became a form of address for the person who was king[5] and Son of god Ra. "The Egyptian sun god Ra, considered the father of all pharaohs, was said to have created himself from a pyramid-shaped mound of earth before creating all other gods." (Donald B. Redford, Ph.D., Penn State) [6]

The term pharaoh ultimately was derived from a compound word represented as pr-`3, written with the two biliteral hieroglyphs pr "house" and `3 "column". It was used only in larger phrases such as smr pr-`3 'Courtier of the High House', with specific reference to the buildings of the court or palace.[7] From the twelfth dynasty onward the word appears in a wish formula 'Great House, may it live, prosper, and be in health', but again only with reference to the royal palace and not the person.

The earliest instance where pr-`3 is used specifically to address the ruler is in a letter to Amenhotep IV (Akhenaten), who reigned c. 1353 - 1336 BCE, which is addressed to 'Pharaoh, all life, prosperity, and health!.[8] During the eighteenth dynasty (sixteenth to fourteenth centuries BCE) the title pharaoh was employed as a reverential designation of the ruler. About the late twenty-first dynasty (tenth century BCE), however, instead of being used alone as before, it began to be added to the other titles before the ruler's name, and from the twenty-fifth dynasty (eighth to seventh centuries BCE) it was, at least in ordinary usage, the only epithet prefixed to the royal appellative.[9]

From the nineteenth dynasty onward pr-`3 on its own was used as regularly as hm.f, 'Majesty'. The term therefore evolved from a word specifically referring to a building to a respectful designation for the ruler, particularly by the twenty-second dynasty and twenty-third dynasty. [citation needed]

For instance, the first dated instance of the title pharaoh being attached to a ruler's name occurs in Year 17 of Siamun on a fragment from the Karnak Priestly Annals. Here, an induction of an individual to the Amun priesthood is dated specifically to the reign of Pharaoh Siamun. This new practice was continued under his successor Psusennes II and the twenty-first dynasty kings. Meanwhile the old custom of referring to the sovereign simply as pr-`3 continued in traditional Egyptian narratives.[citation needed]

By this time, the Late Egyptian word is reconstructed to have been pronounced *par-ʕoʔ whence comes Ancient Greek φαραώ pharaō and then Late Latin pharaō. From the latter, English obtained the word "Pharaoh". Over time, *par-ʕoʔ evolved into Sahidic Coptic prro ⲡⲣ̅ⲣⲟ and then rro (by mistaking p- as the definite article prefix "the" from Ancient Egyptian p3).[10]

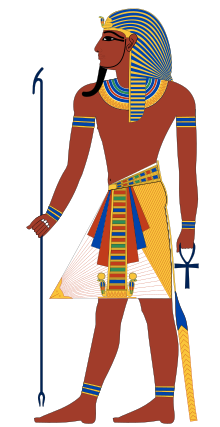

Regalia

Scepters and staves

Scepters and staves were a general sign of authority in Ancient Egypt. One of the earliest royal scepters was discovered in the tomb of Khasekhemwy in Abydos. Kings were also known to carry a staff, and Pharaoh Anedjib is shown on stone vessels carrying a so called mks-staff. The scepter with the longest history seems to be the heqa-scepter, sometimes described as the shepherd’s crook. The earliest examples of this piece of regalia dates to pre-dynastic times. A scepter was found in a tomb at Abydos that dates to the late Naqada period.

Another scepter associated with the king is the was-scepter. This is a long staff mounted with an animal head. The earliest known depictions of the was-scepter date to the first dynasty. The was-scepter is shown in the hands of both kings and deities.

The Flail later was closely related to the ‘’heqa’’-scepter, but in early representations the king was also depicted solely with the flail, as shown in a late pre-dynastic knife handle which is now in the Metropolitan museum, and on the Narmer Macehead.[11]

The Uraeus

The earliest evidence we have of the use of the Uraeus—a rearing cobra—is from the reign of Den from the first dynasty. The cobra supposedly protected the pharaoh by spitting fire at its enemies.[11]

Crowns and headdresses

|

|

| Narmer wearing the white crown | Narmer wearing the red crown |

The red crown of Lower Egypt – the Deshret crown – dates back to pre-dynastic times. A red crown has been found on a pottery shard from Naqada, and later, king Narmer is shown wearing the red crown on both the Narmer macehead and the Narmer palette.

The white crown of Upper Egypt – the Hedjet crown – is shown on the Qustul incense burner which dates to the pre-dynastic period. Later, King Scorpion was depicted wearing the white crown, as was Narmer.

The combination of red and white crown into the double crown – or Pschent crown – is first documented in the middle of the first dynasty. The earliest depiction may date to the reign of Djet, and is otherwise surely attested during the reign of Den.[11]

Khat and nemes headdresses

The khat headdress consists of a kind of “kerchief” whose end is tied similarly to a ponytail. The earliest depictions of the khat headdress comes from the reign of Den, but is not found again until the reign of Djoser.

The Nemes headdress dates from the time of Djoser. The statue from his Serdab in Saqqara shows the king wearing the nemes headdress.[11]

Physical evidence

Egyptologist Bob Brier has noted that despite its widespread depiction in royal portraits, no ancient Egyptian crown ever has been discovered. Tutankhamun's tomb, discovered largely intact, did contain such regalia as his crook and flail, but no crown was found however among the funerary equipment. Diadems have been discovered.[12]

It is presumed that crowns would have been believed to have magical properties. Brier's speculation is that crowns were religious or state items, so it is likely that a dead pharaoh could not retain a crown as a personal possession. The crowns may have been passed along to the successor. [citation needed]

Titles

During the early dynastic period kings had as many as three titles. The Horus name is the oldest and dates to the late pre-dynastic period. The Nesw Bity name was added during the middle of the first dynasty. The Nebty name was first introduced toward the end of the first dynasty.[11] The Golden falcon (bik-nbw) name is not well understood. The prenomen and nomen were introduced later and are traditionally enclosed in a cartouche.[4] By the Middle Kingdom, the official titulary of the ruler consisted of five names; Horus, nebty, golden Horus, nomen, and prenomen [13] for some rulers, only one or two of them may be known.

Nesw Bity name

The Nesw Bity name was one of the new developments from the reign of Den. The name would follow the glyphs for the “Sedge and the Bee”. The title is usually translated as king of Upper and Lower Egypt. The nsw bity name may have been the birth name of the king. It was often the name by which kings were recorded in the later annals and king lists.[11]

Horus name

The Horus name was adopted by the king, when taking the throne. The name was written within a square frame representing the palace, named a serekh. The earliest known example of a serekh dates to the reign of king Ka, before the first dynasty.[14] The Horus name of several early kings expresses a relationship with Horus. Aha refers to “Horus the fighter”, Djer refers to “Horus the strong”, etc. Later kings express ideals of kingship in their Horus names. Khasekhemwy refers to “Horus: the two powers are at peace”, while Nebra refers to “Horus, Lord of the Sun”.[11]

Nebty name

The earliest example of a nebty name comes from the reign of king Aha from the first dynasty. The title links the king with the goddesses of Upper and Lower Egypt Nekhbet and Wadjet.[4][11] The title is preceded by the vulture (Nekhbet) and the cobra (Wadjet) standing on a basket (the neb sign).[11]

Golden Horus

The Golden Horus or Golden Falcon name was preceded by a falcon on a gold or nbw sign. The title may have represented the divine status of the king. The Horus associated with gold may be referring to the idea that the bodies of the deities were made of gold and the pyramids and obelisks are representations of (golden) sun-rays. The gold sign may also be a reference to Nubt, the city of Set. This would suggest that the iconography represents Horus conquering Set.[11]

Nomen and prenomen

The prenomen and nomen were contained in a cartouche. The prenomen often followed the King of Upper and Lower Egypt (nsw bity) or Lord of the Two Lands (nebtawy) title. The prenomen often incorporated the name of Re. The nomen often followed the title Son of Re (sa-ra) or the title Lord of Appearances (neb-kha’).[4]

See also

- Egyptian chronology - Conventional Egyptian chronology

- Great Royal Wife, the chief wife of a male pharaoh

- History of Egypt

- Islamic view of the Pharaoh of the Exodus

- List of Pharaohs

- Monarch

- Pharaoh of the Exodus

References

- ^ Merriam-Webster's Collegiate Dictionary, Eleventh Edition. Merriam-Webster, 2007. p. 928

- ^ a b Dictionary Reference: pharaoh

- ^ Beck (1999). World History: Patterns of Interaction. Evanston, IL: McDougal Littell. ISBN 0-395-87274-X.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|1st=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help)CS1 maint: extra punctuation (link) - ^ a b c d Dodson, Aidan and Hilton, Dyan. The Complete Royal Families of Ancient Egypt. Thames & Hudson. 2004. ISBN 0-500-05128-3

- ^ Redmount, Carol A. "Bitter Lives: Israel in and out of Egypt." p. 89-90. The Oxford History of the Biblical World. Michael D. Coogan, ed. Oxford University Press. 1998.

- ^ Redford, Donald B., Ph.D.; McCauley, Marissa. "How were the Egyptian pyramids built?". Research. The Pennsylvania State University. Retrieved 11 December 2012.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Ancient Egyptian Grammar (3rd ed.), A. Gardiner (1957-) 71-76

- ^ Hieratic Papyrus from Kahun and Gurob, F. LL. Griffith, 38, 17. Although see also Temples of Armant, R. Mond and O. Myers (1940), pl.93, 5 for an instance possibly dating from the reign of Thutmose III.

- ^ "pharaoh." in Encyclopædia Britannica. Ultimate Reference Suite. Chicago: Encyclopædia Britannica, 2008.

- ^ Walter C. Till: Koptische Grammatik. VEB Verläg Enzyklopädie, Leipzig, 1961. p.62

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Wilkinson, Toby A.H. Early Dynastic Egypt Routledge, 2001 ISBN 978-0-415-26011-4

- ^ Shaw, Garry J. The Pharaoh, Life at Court and on Campaign. Thames and Hudson, 2012, p.21, 77.

- ^ Ian Shaw, The Oxford History of Ancient Egypt, Oxford University Press 2000, p. 477

- ^ Toby A. H. Wilkinson, Early Dynastic Egypt, Routledge 1999, pp.57f.

Bibliography

- Shaw, Garry J. The Pharaoh, Life at Court and on Campaign, Thames and Hudson, 2012.

- Sir Alan Gardiner Egyptian Grammar: Being an Introduction to the Study of Hieroglyphs, Third Edition, Revised. London: Oxford University Press, 1964. Excursus A, pp. 71–76.

- Jan Assmann, "Der Mythos des Gottkönigs im Alten Ägypten," in Christine Schmitz und Anja Bettenworth (hg.), Menschen - Heros - Gott: Weltentwürfe und Lebensmodelle im Mythos der Vormoderne (Stuttgart, Franz Steiner Verlag, 2009), 11-26.

External links

- Digital Egypt for Universities

- Mummies of the Pharaohs at James M. Deem's Mummy Tombs site.