Economy of Namibia

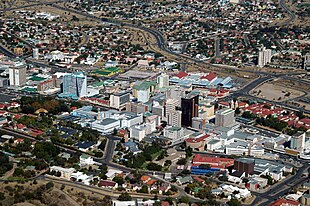

Windhoek, the capital and economic centre of Namibia | |

| Currency |

|

|---|---|

| 1 ZAR = 1 NAD | |

| 1 April – 31 March | |

Trade organisations | AU, AfCFTA, WTO, SADC, SACU |

Country group |

|

| Statistics | |

| Population | |

| GDP | |

| GDP rank | |

GDP growth |

|

GDP per capita | |

GDP per capita rank | |

GDP by sector |

|

| 2.4% (2020 est.)[5] | |

Population below poverty line | 17.4% (2015, World Bank)[7] |

| 59.1 high (2015, World Bank)[8] | |

Labour force | |

Labour force by occupation |

|

| Unemployment | |

Main industries | meatpacking, fish processing, dairy products, pasta, beverages; mining (diamonds, lead, zinc, tin, silver, tungsten, uranium, copper) |

| External | |

| Exports | |

Export goods | diamonds, copper, gold, zinc, lead, uranium; cattle, white fish and mollusks |

Main export partners |

|

| Imports | |

Import goods | foodstuffs; petroleum products and fuel, machinery and equipment, chemicals |

Main import partners | |

FDI stock | |

Gross external debt | |

| Public finances | |

| −5.5% (of GDP) (2017 est.)[6] | |

| Revenues | 4.268 billion (2017 est.)[6] |

| Expenses | 5 billion (2017 est.)[6] |

| Economic aid | recipient: ODA, $160 million (2000) |

All values, unless otherwise stated, are in US dollars. | |

The economy of Namibia has a modern market sector, which produces most of the country's wealth, and a traditional subsistence sector. Although the majority of the population engages in subsistence agriculture and herding, Namibia has more than 200,000 skilled workers and a considerable number of well-trained professionals and managerials.[13]

Overview

Namibia is a higher-middle-income country with an estimated annual GDP per capita of US$5,828 but has extreme inequalities in income distribution and standard of living.[14] It has the second-highest Gini coefficient out of all nations, with a coefficient of 59.1 as of 2015.[15] Only South Africa has a higher Gini coefficient.[16]

Since independence, the Namibian Government has pursued free-market economic principles designed to promote commercial development and job creation to bring disadvantaged Namibians into the economic mainstream. To facilitate this goal, the government has actively courted donor assistance and foreign investment. The liberal Foreign Investment Act of 1990 provides guarantees against nationalisation, freedom to remit capital and profits, currency convertibility, and a process for settling disputes equitably. Namibia also is addressing the sensitive issue of agrarian land reform in a pragmatic manner. However, the government runs and owns a number of companies such as TransNamib and NamPost, most of which need frequent financial assistance to stay afloat.[17][18]

The country's sophisticated formal economy is based on capital-intensive industry and farming. However, Namibia's economy is heavily dependent on the earnings generated from primary commodity exports in a few vital sectors, including minerals, especially diamonds, livestock, and fish. Furthermore, the Namibian economy remains integrated with the economy of South Africa, as 47% of Namibia's imports originate from there.[15]

In 1993, Namibia became a signatory of the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT), and the Minister of Trade and Industry represented Namibia at the Marrakech signing of the Uruguay Round Agreement in April 1994. Namibia also is a member of the International Monetary Fund and the World Bank.

In January 2021, President Hage Geingob formed the Namibia Investment Promotion and Development Board (NIPDB) led by Nangula Nelulu Uaandja. The NIPDB commenced operations as an autonomous entity in the Namibian Presidency and was established to reform the country's economic sector.

Regional integration

Given its small domestic market but favourable location and a superb transport and communications base, Namibia is a leading advocate of regional economic integration. In addition to its membership in the Southern African Development Community (SADC), Namibia presently belongs to the Southern African Customs Union (SACU) with South Africa, Botswana, Lesotho, and Eswatini. Within SACU, there is no customs on goods produced in, and being transported amidst, its members.[13][19] Namibia is a net receiver of SACU revenues; they are estimated to contribute 13.9 billion NAD in 2012.[20]

The Namibian economy is closely linked to South Africa with the Namibian dollar pegged to the South African rand. Privatisation of several enterprises in coming years may stimulate long-run foreign investment, although with the trade union movement opposed, so far most politicians have been reluctant to advance the issue. In September 1993, Namibia introduced its own currency, the Namibia Dollar (N$), which is linked to the South African Rand at a fixed exchange rate of 1:1. There has been widespread acceptance of the Namibia Dollar throughout the country and, while Namibia remains a part of the Common Monetary Area, it now enjoys slightly more flexibility in monetary policy although interest rates have so far always moved very closely in line with the South African rates.[citation needed]

Namibia imports almost all of its goods from South Africa. Many exports likewise go to the South African market, or transit that country.[13] Namibia's exports consist mainly of diamonds and other minerals, fish products, beef and meat products, karakul sheep pelts, and light manufactures. In recent years, Namibia has accounted for about 5% of total SACU exports, and a slightly higher percentage of imports.[citation needed]

Namibia is seeking to diversify its trading relationships away from its heavy dependence on South African goods and services. Europe has become a leading market for Namibian fish and meat, while mining concerns in Namibia have purchased heavy equipment and machinery from Germany, the United Kingdom, the United States, and Canada. The Government of Namibia is making efforts to take advantage of the American-led African Growth and Opportunity Act (AGOA), which will provide preferential access to American markets for a long list of products. In the short term, Namibia is likely to see growth in the apparel manufacturing industry as a result of AGOA.[citation needed]

Data

The following table shows the main economic indicators in 1990–2017.[21]

| Year | 1990 | 1995 | 2000 | 2005 | 2006 | 2007 | 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GDP in $ (PPP) |

5.55 Bln. | 7.60 Bln. | 9.82 Bln. | 13.92 Bln. | 14.91 Bln. | 15.87 Bln. | 16.61 Bln. | 16.78 Bln. | 18.02 Bln. | 19.32 Bln. | 20.68 Bln. | 22.19 Bln. | 24.02 Bln. | 25.74 Bln. | 26.35 Bln. | 26.51 Bln. |

| GDP per capita in $ (PPP) |

4,124 | 4,769 | 5,373 | 7,112 | 7,486 | 7,959 | 8,207 | 8,171 | 8,641 | 9,132 | 9,592 | 10,104 | 10,734 | 11,284 | 11,335 | 11,311 |

| GDP growth (real) |

... | 4.1 % | 3.5 % | 4.7 % | 3.9 % | 3.6 % | 2.7 % | 0.3 % | 6.0 % | 5.1 % | 5.0 % | 5.6 % | 6.4 % | 6.0 % | 1.1 % | −1.2 % |

| Inflation (in Percent) |

... | 11.1 % | 10.2 % | 2.3 % | 5.0 % | 6.5 % | 9.1 % | 9.5 % | 4.9 % | 5.0 % | 6.7 % | 5.6 % | 5.3 % | 3.4 % | 6.7 % | 6.1 % |

| Government debt (Percentage of GDP) |

... | 20 % | 21 % | 27 % | 25 % | 19 % | 19 % | 16 % | 16 % | 27 % | 25 % | 25 % | 25 % | 40 % | 45 % | 46 % |

Sectors

Namibia is heavily dependent on the extraction and processing of minerals for export. Taxes and royalties from mining account for 25% of its revenue.[22] The bulk of the revenue is created by diamond mining, which made up 7.2% of the 9.5% that mining contributes to Namibia's GDP in 2011.[23] Rich alluvial diamond deposits make Namibia a primary source for gem-quality diamonds. Namibia is a large exporter of uranium and over the years the mining industry has seen a decline in the international commodity prices such as uranium, which has led to the reason behind several uranium projects being abandoned. Experts say that the prices are expected to rise in the next 3 years because of an increase in nuclear activities from both Japan and China.

Mining and energy

Diamond production totalled 1.5 million carats (300 kg) in 2000, generating nearly $500 million in export earnings. Other important mineral resources are uranium, copper, lead, and zinc. The country also extracts gold, silver, tin, vanadium, semiprecious gemstones, tantalite, phosphate, sulphur, and mines salt.[13]

Namibia is the fourth-largest exporter of nonfuel minerals in Africa, the world's fourth-largest producer of uranium, and the producer of large quantities of lead, zinc, tin, silver, and tungsten. Namibia has two uranium mines that are capable of providing 10% of the world mining output.[1] The mining sector employs only about 3% of the population while about half of the population depends on subsistence agriculture for its livelihood. Namibia normally imports about 50% of its cereal requirements; in drought years food shortages are a major problem in rural areas.[24]

During the pre-independence period, large areas of Namibia, including off-shore, were leased for oil prospecting. Some natural gas was discovered in 1974 in the Kudu Field off the mouth of the Orange River, but the extent of this find is only now being determined.[25] It is only in 2022 with the Graff discovery[26] of Shell and the Venus discovery[27] of TotalEnergies that Namibia became a true expoloration frontier.

Agriculture

About half of the population depends on agriculture (largely subsistence agriculture) for its livelihood, but Namibia must still import some of its food. Although per capita GDP is five times the per capita GDP of Africa's poorest countries, the majority of Namibia's people live in rural areas and exist on a subsistence way of life. Namibia has one of the highest rates of income inequality in the world, due in part to the fact that there is an urban economy and a more rural cash-less economy. The inequality figures thus take into account people who do not actually rely on the formal economy for their survival. Although arable land accounts for only 1% of Namibia, nearly half of the population is employed in agriculture.[28]

About 4,000, mostly white, commercial farmers own almost half of Namibia's arable land.[29] Agreement has been reached on the privatisation of several more enterprises in coming years, with hopes that this will stimulate much needed foreign investment. However, reinvestment of environmentally derived capital has hobbled Namibian per capita income.[30]

One of the fastest growing areas of economic development in Namibia is the growth of wildlife conservancies. These conservancies are particularly important to the rural generally unemployed population.[citation needed]

Agriculture is increasingly under pressure, due to factors such as frequent and prolonged droughts as well as bush encroachment. These render conventional agriculture unsustainable for a growing number of land owners, with many diverting their economic activities to alternative of additional sources of income.[31]

In recent years, the utilisation of residual biomass that results from the control of woody plant encroachment has gained traction.[32] In 2022, Namibia was the seventh largest exporter of charcoal globally, with total export volumes of over 280,000 tonnes and revenues of USD 75 million.[33] Other products from local encroacher biomass include bush-based animal fodder[34][35], wood-plastic composite materials[36], thermal energy in a cement factory[37] and a brewery[38] and biochar.[citation needed] In 2019 it was estimated that 10,000 workers were employed in the growing sub-sector of biomass utilisation, rendering it one of the biggest sub-sectors in terms of employment.[39][40]

Fishing

The clean, cold South Atlantic waters off the coast of Namibia are home to some of the richest fishing grounds in the world, with the potential for sustainable yields of 1.5 million tonnes per year. Commercial fishing and fish processing is the fastest-growing sector of the Namibian economy in terms of employment, export earnings, and contribution to GDP.[41]

The main species found in abundance off Namibia are pilchards (sardines), anchovy, hake, and horse mackerel. There also are smaller but significant quantities of sole, squid, deep-sea crab, rock lobster, and tuna.[42] At the time of independence, fish stocks had fallen to dangerously low levels, due to the lack of protection and conservation of the fisheries and the over-exploitation of these resources. This trend appears to have been halted and reversed since independence, as the Namibian Government is now pursuing a conservative resource management policy along with an aggressive fisheries enforcement campaign. The government seeks to develop fish-farming as an alternative and has prioritised it as part of Vision 2030 and NDP2.[43]

On 12 November 2019, WikiLeaks published thousands of documents and email communication by Samherji's employees, called the Fishrot Files, that indicated hundreds of millions ISK had been paid to high ranking politicians and officials in Namibia with the objective of acquiring the country's coveted fishing quota.[44]

Manufacturing and infrastructure

In 2000, Namibia's manufacturing sector contributed about 20% of GDP. Namibian manufacturing is inhibited by a small domestic market, dependence on imported goods, limited supply of local capital, widely dispersed population, small skilled labour force and high relative wage rates, and subsidised competition from South Africa.

Walvis Bay is a well-developed, deepwater port, and Namibia's fishing infrastructure is most heavily concentrated there. The Namibian Government expects Walvis Bay to become an important commercial gateway to the Southern African region.

Namibia also boasts world-class civil aviation facilities and an extensive, well-maintained land transportation network. Construction is underway on two new arteries—the Trans-Caprivi Highway and Trans-Kalahari Highway—which will open up the region's access to Walvis Bay.

The Walvis Bay Export Processing Zone operates in the key port of Walvis Bay.

Tourism

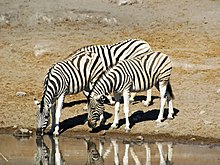

Tourism is a major contributor (14.5%) to Namibia's GDP, creating tens of thousands of jobs (18.2% of all employment) directly or indirectly and servicing over a million tourists per annum.[45] The country is among the prime destinations in Africa and is known for ecotourism which features Namibia's extensive wildlife.[46]

There are many lodges and reserves to accommodate eco-tourists. Sport Hunting is also a large, and growing component of the Namibian economy, accounting for 14% of total tourism in the year 2000, or $19.6 million US dollars, with Namibia boasting numerous species sought after by international sport hunters.[47] In addition, extreme sports such as sandboarding, skydiving and 4x4ing have become popular, and many cities have companies that provide tours. The most visited places include the Caprivi Strip, Fish River Canyon, Sossusvlei, the Skeleton Coast Park, Sesriem, Etosha Pan and the coastal towns of Swakopmund, Walvis Bay and Lüderitz.[48]

In 2020, it would be estimated that tourism would bring is $26 million Namibian dollars however due to the COVID-19 pandemic, Namibia saw a reduction of almost 90% in tourism. In the third quarter of 2021, there was an increase in tourism, however, it is estimated that it will be until 2023 when tourism returns to some kind of normality.

Labour

While many Namibians are economically active in one form or another, the bulk of this activity is in the informal sector, primarily subsistence agriculture. A large number of Namibians seeking jobs in the formal sector are held back due to a lack of necessary skills or training. The government is aggressively pursuing education reform to overcome this problem.

Namibia has a high unemployment rate. "Strict unemployment" (people actively seeking a full-time job) stood at 20.2% in 1999, 21.9% in 2002, and spiraled to 29,4 per cent in 2008.[49] A 2012 study by the Namibia Statistics Agency (NSA) determined the rate of unemployment to be 27.4%. This study included subsistence farmers, work without pay, and any non-zero amount of weekly working hours, and did not count as unemployed people not actively seeking for a job.[50]

Under a much broader definition (including people that have given up searching for employment) two different studies determined the unemployment rate to be 36.7% (2004) and 51.2% (2008), respectively. This estimate considers people in the informal economy as employed. 72% of jobless people have been unemployed for two years or more. Labour and Social Welfare Minister Immanuel Ngatjizeko praised the 2008 study as "by far superior in scope and quality to any that has been available previously",[51] but its methodology has also received criticism.[49] The total number of formally employed people stood at 400,000 in 1997 and fell 330,000 in 2008, according to a government survey. The NSA 2012 study counted 396,000 formal employees. Of annually 25,000 school leavers only 8,000 gain formal employment—largely a result of a failed education system.[50][52]

Namibians in the informal sector as well as in low-paid jobs like homemakers, gardeners or factory workers are unlikely to be covered by medical aid or a pension fund. All in all only a quarter or the working population have medical aid, and about half have a pension fund.[53]

Namibia's largest trade union federation, the National Union of Namibian Workers (NUNW) represents workers organised into seven affiliated trade unions. NUNW maintains a close affiliation with the ruling SWAPO party.

Household wealth and income

In the financial year March 2009 – February 2010, every Namibian earned 15,000 N$ (roughly 2,000 US$) on average. Household income was dominated by wages (49.1%) and subsistence farming (23%), with further significant sources of income being business activities (8.1%, farming excluded), old-age pensions from government (9.9%), and cash remittance (2.9%). Commercial farming only contributed 0.6%.[54]

Every Namibian resident had on average 10,800 US$ of wealth accumulated in 2016, putting Namibia on third place in Africa. Individual wealth is, however, distributed very unequally; the country's Gini coefficient of 0.61 is one of the highest in the world. There are 3,300 US$-millionaires in Namibia, 1,400 of which live in the capital Windhoek.[55]

Namibian businesspeople

- Benjamin Hauwanga[56]

- Frans Indongo[57]

- Monica Kalondo

- Harold Pupkewitz (1915–2012)[58]

- Wilhelm Sander (1860–1930)[59]

- Sven Thieme

See also

- Bank of Namibia

- List of state-owned enterprises in Namibia

- United Nations Economic Commission for Africa

Notes

References

![]() This article incorporates public domain material from The World Factbook. CIA.

This article incorporates public domain material from The World Factbook. CIA.

- ^ "World Economic Outlook Database, April 2019". IMF.org. International Monetary Fund. Retrieved 29 September 2019.

- ^ "World Bank Country and Lending Groups". datahelpdesk.worldbank.org. World Bank. Retrieved 29 September 2019.

- ^ "Population, total". data.worldbank.org. World Bank. Retrieved 24 August 2019.

- ^ a b c "World Economic Outlook Database, October 2019". IMF.org. International Monetary Fund. Retrieved 19 January 2020.

- ^ a b c "World Economic Outlook Database, April 2020". IMF.org. International Monetary Fund. Retrieved 20 April 2020.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q "The World Factbook". CIA.gov. Central Intelligence Agency. Retrieved 28 March 2019.

- ^ "Poverty headcount ratio at national poverty lines (% of population)". data.worldbank.org. World Bank. Retrieved 28 March 2019.

- ^ "GINI index (World Bank estimate)". data.worldbank.org. World Bank. Retrieved 28 March 2019.

- ^ "Human Development Index (HDI)". hdr.undp.org. HDRO (Human Development Report Office) United Nations Development Programme. Retrieved 23 November 2022.

- ^ "Inequality-adjusted Human Development Index (IHDI)". hdr.undp.org. HDRO (Human Development Report Office) United Nations Development Programme. Retrieved 23 November 2022.

- ^ "Labor force, total". data.worldbank.org. World Bank. Retrieved 19 January 2020.

- ^ "Employment to population ratio, 15+, total (%) (national estimate)". data.worldbank.org. World Bank. Retrieved 24 August 2019.

- ^ a b c d "Namibia (04/95)". U.S. Department of State. Retrieved 2 June 2017.

- ^ "Independent Evaluation of the UNDP Country Programme Document" (doc). UNDP. Retrieved 7 July 2010.

- ^ a b "Namibia", The World Factbook, Central Intelligence Agency, 22 September 2021, retrieved 23 September 2021

- ^ "Gini Index coefficient – distribution of family income - The World Factbook". www.cia.gov. Retrieved 23 September 2021.

- ^ "Government income from SOEs 2013/2014-2015-2016". Insight Namibia. April 2013. p. 21.

- ^ "Payments and transfers to SOEs 2013/2014-2015-2016". Insight Namibia. April 2013. p. 22.

- ^ "** Welcome to the SACU Website **". www.sacu.int. Retrieved 30 May 2020.

- ^ Nyaungwa, Nyasha Francis (5 April 2012). "Domestic debt above N$17 bn". Namibia Economist. Archived from the original on 11 June 2012.

- ^ "Report for Selected Countries and Subjects". Retrieved 9 September 2018.

- ^ Mining In Namibia, NIED information sheet Archived 10 May 2011 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Duddy, Jo-Maré (27 November 2012). "Mining remains gem of economy". The Namibian. Archived from the original on 11 January 2013.

- ^ "Namibia's food security improves... No major price increases for cereals - Namibia". ReliefWeb. Retrieved 14 October 2021.

- ^ Namibia (02/05), U.S. Department of State. (n.d.) Retrieved 26 June 2022

- ^ Esau (i_esau), Iain (6 April 2022). "Happy days: Shell's Graff discovery in Namibia holds 2 billion boe of oil and gas - sources | Upstream Online". Upstream Online | Latest oil and gas news. Retrieved 24 August 2022.

- ^ "Namibie : TotalEnergies fait une découverte significative sur le bloc 2913B". TotalEnergies.com (in French). Retrieved 24 August 2022.

- ^ World Almanac. 2004.

- ^ LaFraniere, Sharon (25 December 2004) Tensions Simmer as Namibia Divides Its Farmland", The New York Times

- ^ Lange, Glenn-Marie (2004). "Wealth, Natural Capital, and Sustainable Development: Contrasting Examples from Botswana and Namibia". Environmental & Resource Economics. 29 (3): 257–83. doi:10.1007/s10640-004-4045-z. S2CID 155085174.

- ^ New Era. "Bush encroachment wrecks 45 million hectares". Truth, for its own sake. Retrieved 21 October 2023.

- ^ "Biomass sector will grow significantly over the next years – Mungunda | Namibia Economist". Retrieved 21 October 2023.

- ^ "Trade Map - List of exporters for the selected product in 2022 (Wood charcoal, incl. shell or nut charcoal, whether or not agglomerated (excl. wood charcoal ...)". www.trademap.org. Retrieved 21 October 2023.

- ^ "Bush-based animal feed viable for farming - DAS". New Era. 9 June 2020. Retrieved 14 June 2020.

- ^ Mupangwa, Johnfisher; Lutaaya, Emmanuel; Shipandeni, Maria Ndakula Tautiko; Kahumba, Absalom; Charamba, Vonai; Shiningavamwe, Katrina Lugambo (2023), Fanadzo, Morris; Dunjana, Nothando; Mupambwa, Hupenyu Allan; Dube, Ernest (eds.), "Utilising Encroacher Bush in Animal Feeding", Towards Sustainable Food Production in Africa, Singapore: Springer Nature Singapore, pp. 239–265, doi:10.1007/978-981-99-2427-1_14, ISBN 978-981-99-2426-4, retrieved 21 October 2023

- ^ "Acacia-Composites | WPC | Decking | Made in Namibia | South Africa | Europe | Windhoek". Acacia-Composites. Retrieved 21 October 2023.

- ^ "Ohorongo Cement: Fuel". Ohorongo Cement. Retrieved 21 October 2023.

- ^ "The brewery using bush biomass". akzente. Retrieved 21 October 2023.

- ^ "Charcoal industry now employs some 10 000 workers". New Era. August 2019. Retrieved 14 June 2020.

- ^ "Biomass sector will grow significantly over the next years – Mungunda". Namibia Economist. 12 August 2019. Retrieved 14 June 2020.

- ^ Chiripanhura, Teweldemedhin, Blessing, Mogos (2016). An Analysis of the Fishing Industry in Namibia: The Structure, Performance, Challenges, and Prospects for Growth and Diversification. Namibia: African Growth and Development Policy. pp. 17–18.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "Marine life in Namibia". namibian.org. Namibia Safari2go. Retrieved 26 October 2022.

- ^ "Namibia's Aquaculture Strategic Plan". May 2004. Retrieved 28 February 2023.

- ^ Helgi Seljan; Aðalsteinn Kjartansson; Stefán Aðalsteinn Drengsson. "What Samherji wanted hidden". RÚV (in Icelandic). Retrieved 13 November 2019.

- ^ "A Framework/Model to Benchmark Tourism GDP in South Africa". Pan African Research & Investment Services. March 2010. p. 34. Archived from the original on 18 July 2010.

- ^ Hartman, Adam (30 September 2009). "Tourism in good shape – Minister". The Namibian.

- ^ Humavindu, Michael N.; Barnes, Jonothan I (October 2003). "Trophy Hunting in the Namibian Economy: An Assessment. Environmental Economics Unit, Directorate of Environmental Affairs, Ministry of Environment and Tourism, Namibia". South African Journal of Wildlife Research. 33 (2): 65–70.

- ^ "Namibia top tourist destinations". Namibiatourism.com.na. Archived from the original on 27 December 2016.

- ^ a b Ndjebela, Toivo (18 November 2011). "Mwinga speaks out on his findings". New Era. via allafrica.com. Archived from the original on 12 January 2013. Retrieved 23 February 2012.

- ^ a b Steytler, John (April 2013). "The Namibia Labour Force Survey 2012 Report" (PDF). Namibia Statistics Agency. pp. vi, viii, 9, 11. Archived from the original (PDF) on 22 February 2014.

- ^ "Half of all Namibians unemployed" by Jo-Mare Duddy, The Namibian, 4 February 201 Archived 9 February 2010 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Ekongo, John (6 August 2010). "Namibians unemployable, say experts". New Era.

- ^ Kaira, Chamwe (27 May 2016). "Social Security pension, medical funds long way off". The Namibian. p. 19.

- ^ "Household Sources of Income". Insight Namibia. August 2012. p. 13.

- ^ Nakashole, Ndama (24 April 2017). "Namibians 3rd wealthiest people in Africa". The Namibian. p. 13.

- ^ "Laureate Ben Hauwanga | Junior Achievement Namibia". Ja-namibia.org. Archived from the original on 2 April 2012. Retrieved 2 July 2012.

- ^ Frans Indongo Archived 22 July 2011 at the Wayback Machine at the Namibia Institute for Democracy, 2007

- ^ Schlechter, Deon (1 August 2002). "Harold Pupkewitz, grootste onder die grotes" [Harold Pupkewitz, biggest among the big]. Die Republikein (in Afrikaans).

- ^ Dierks, Klaus. "Biographies of Namibian Personalities, S". klausdierks.com. Retrieved 2 July 2012.

External links

- Template:Curlie

- Namibia latest trade data on ITC Trade Map

- Unit Trusts Investment in Namibia

- MBendi Namibia overview

- Namibia Economic Policy Research Unit autonomous economic policy research organisation