Bannack, Montana

Bannack Historic District | |

Main street in Bannack | |

| Location | Beaverhead County, Montana |

|---|---|

| Nearest city | Dillon, Montana |

| Coordinates | 45°09′40″N 112°59′44″W / 45.16111°N 112.99556°W |

| Area | 1 mile (1.6 km) |

| Built | 1862 |

| NRHP reference No. | 66000426 |

| Significant dates | |

| Added to NRHP | October 15, 1966 |

| Designated NHLD | July 4, 1961[1] |

Bannack is a ghost town in Beaverhead County, Montana, United States, located on Grasshopper Creek, approximately 11 miles (18 km) upstream from where Grasshopper Creek joins with the Beaverhead River south of Dillon. Founded in 1862, the town contemporarily operates as a National Historic Landmark and is managed by the state of Montana as Bannack State Park.[2]

History

Founded in 1862 and named after the local Bannock Indians, it was the site of a major gold discovery in 1862, and served as the capital of Montana Territory briefly in 1864, until the capital was moved to Virginia City. Bannack continued as a mining town, though with a dwindling population. The last residents left in the 1970s.

At its peak, Bannack had a population of about ten thousand. Extremely remote, it was connected to the rest of the world only by the Montana Trail. There were three hotels, three bakeries, three blacksmith shops, two stables, two meat markets, a grocery store, a restaurant, a brewery, a billiard hall, and four saloons. Though all of the businesses were built of logs, some had decorative false fronts.

Among the town's founders was Dr. Erasmus Darwin Leavitt, a physician born in Cornish, New Hampshire, who gave up medicine for a time to become a gold miner. Dr. Leavitt arrived in Bannack in 1862, and alternately practiced medicine and mined for gold with pick and shovel. "Though some success crowned his labors," according to a history of Montana by Joaquin Miller, "he soon found that he had more reputation as a physician than as a miner, and that there was greater profit in allowing someone else to wield his pick and shovel while he attended to his profession." Subsequently, Dr. Leavitt moved on to Butte, Montana, where he devoted the rest of his life to his medical practice [3]

Bannack's sheriff, Henry Plummer, was accused by some of secretly leading a ruthless band of road agents, with early accounts claiming that this gang was responsible for over a hundred murders in the Virginia City and Bannack gold fields and trails to Salt Lake City. However, because only eight deaths are historically documented, some modern historians have called into question the exact nature of Plummer's gang, while others deny the existence of the gang altogether. In any case, Plummer and two compatriots, both deputies, were hanged, without trial, at Bannack on January 10, 1864. A number of Plummer's associates were lynched and others banished on pain of death if they ever returned. Twenty-two individuals were accused, informally tried, and hanged by the Vigilance Committee (the Montana Vigilantes) of Bannack and Virginia City.[4] Nathaniel Pitt Langford, the first superintendent of Yellowstone National Park, was a member of that vigilance committee.[5]

State park

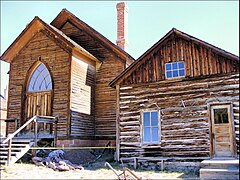

Sixty historic log, brick, and frame structures remain standing in Bannack, many quite well preserved; most can be explored. The site, now the Bannack Historic District, was declared a National Historic Landmark in 1961.[6][7] The town is presently the site of Bannack State Park. Though not particularly popular among tourists, this site remains a favorite for natives and historians alike.

Bannack Days

Every year, during the third weekend of July, this abandoned town witnesses a historical reconstitution known as "Bannack Days". For two days, Bannack State Park officials organize an event that attempts to revive the times when Bannack was a boom town, re-enacting the day-to-day lives of the miners who lived there during the gold rush. An authentic, old-fashioned breakfast is served in the old Hotel Meade, a well-preserved brick building which was for many years the seat of Beaverhead County, before Dillon, Montana, became the seat of the county.[8]

Physiography

The mines surrounding Bannack are located on both sides of Grasshopper Creek, which flows southeastward through the district and into the Beaverhead River about 12 miles (19 km) miles downstream.[9]

Gallery

-

Schoolhouse and Masonic Lodge

-

Hotel Meade

-

Methodist Church, built in 1877

-

Private home in Bannack

-

Family plot in cemetery

-

Historic landmark plaque

See also

- List of ghost towns in Montana

- Montana Ghost Town Preservation Society

- List of National Historic Landmarks in Montana

- National Register of Historic Places listings in Beaverhead County, Montana

References

- ^ "Listing of National Historic Landmarks by State: Montana" (PDF). National Park Service. Archived (PDF) from the original on August 1, 2017. Retrieved June 1, 2018.

- ^ "Bannack State Park". Montana Fish, Wildlife & Parks. Archived from the original on May 24, 2018. Retrieved June 1, 2018.

- ^ Joaquin Miller (1894). "Erasmus Darwin Leavitt". History of Montana. USGENWEB Montana Archives. Archived from the original on 2012-02-26. Retrieved 2009-09-01.

- ^ Hough, Emerson (1907). The Story of the Outlaw. New York: The Outling Publishing Company. pp. 105–126.

- ^ Olin D. Wheeler (1915). "Speech to the Montana Historical Society, April 8, 1912". Nathaniel Pitt Langford: The Vigilante, the Explorer, the Expounder and First Superintendent of Yellowstone Park. Minnesota Historical Society. pp. 631–668.

- ^ "Bannack Historic District". NPGallery. National Park Service. Retrieved June 1, 2018.

- ^ Blanche Higgins Schroer (September 1975). "Bannack Historic District". National Register of Historic Places Inventory Nomination Form. National Park Service. and Accompanying 11 photos, from 1975.

- ^ "Bannack Days". Bannack State Park and Bannack Association. Archived from the original on September 28, 2016. Retrieved July 21, 2012.

- ^ Spectrum Engineering & Abandoned Mine Reclamation Bureau Montana 1992, p. 1.

Bibliography

- Spectrum Engineering; Abandoned Mine Reclamation Bureau Montana (1992). Bannack State Park Project. Billings, Montana: Montana State Library. p. 194.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)

External links

- Bannack State Park Montana Fish, Wildlife & Parks

- Bannack State Park Bannack State Park and Bannack Association

- Populated places in Beaverhead County, Montana

- Ghost towns in Montana

- Populated places established in 1862

- Historic districts on the National Register of Historic Places in Montana

- National Historic Landmarks in Montana

- Former colonial and territorial capitals in the United States

- Mining communities in Montana

- Gold mines in the United States

- Open-air museums in Montana

- Symbols of Montana

- 1862 establishments in Washington Territory

- National Register of Historic Places in Beaverhead County, Montana

- Populated places on the National Register of Historic Places in Montana