Ugarit

Entrance to the Royal Palace of Ugarit | |

| Alternative name | Ras Shamra (Arabic: رأس شمرة) |

|---|---|

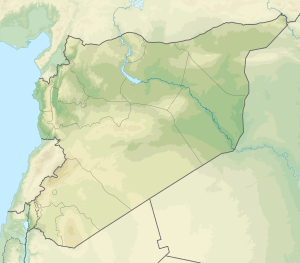

| Location | Latakia Governorate, Syria |

| Region | Fertile Crescent |

| Coordinates | 35°36′07″N 35°46′55″E / 35.602°N 35.782°E |

| Type | settlement |

| History | |

| Founded | c. 6000 BCE |

| Abandoned | c. 1190 BCE |

| Periods | Neolithic–Late Bronze Age |

| Cultures | Canaanite |

| Events | Bronze Age Collapse |

| Site notes | |

| Excavation dates | 1928–present |

| Archaeologists | Claude F. A. Schaeffer |

| Condition | ruins |

| Ownership | Public |

| Public access | Yes |

Ugarit (/ˌuːɡəˈriːt, ˌjuː-/; Ugaritic: 𐎜𐎂𐎗𐎚, ʼUgart; Arabic: أُوغَارِيت Ūġārīt or أُوجَارِيت Ūǧārīt) was an ancient port city in northern Syria, in the outskirts of modern Latakia, discovered by accident in 1928 together with the Ugaritic texts. Its ruins are often called Ras Shamra[1] after the headland where they lie.

Ugarit had close connections to the Hittite Empire, sent tribute to Egypt at times, and maintained trade and diplomatic connections with Cyprus (then called Alashiya), documented in the archives recovered from the site and corroborated by Mycenaean and Cypriot pottery found there. The polity was at its height from c. 1450 BCE until its destruction in c. 1200 BCE; this destruction was possibly caused by the mysterious Sea Peoples or internal struggle. The kingdom would be one of the many destroyed during the Bronze Age Collapse.

History

Ras Shamra lies on the Mediterranean coast, some 11 kilometres (7 mi) north of Latakia, near modern Burj al-Qasab.

Origins and the second millennium

Neolithic Ugarit was important enough to be fortified with a wall early on, perhaps by 6000 BCE, though the site is thought to have been inhabited earlier. Ugarit was important perhaps because it was both a port and at the entrance of the inland trade route to the Euphrates and Tigris lands.[citation needed] The city reached its heyday between 1800 and 1200 BCE, when it ruled a trade-based coastal kingdom, trading with Egypt, Cyprus, the Aegean, Syria, the Hittites, and much of the eastern Mediterranean.[2]

The first written evidence mentioning the city comes from the nearby city of Ebla, c. 1800 BCE. Ugarit passed into the sphere of influence of Egypt, which deeply influenced its art. Evidence of the earliest Ugaritic contact with Egypt (and the first exact dating of Ugaritic civilization) comes from a carnelian bead identified with the Middle Kingdom pharaoh Senusret I, 1971–1926 BCE. A stela and a statuette from the Egyptian pharaohs Senusret III and Amenemhet III have also been found. However, it is unclear at what time these monuments were brought to Ugarit. Amarna letters from Ugarit c. 1350 BCE record one letter each from Ammittamru I, Niqmaddu II, and his queen.[citation needed] From the 16th to the 13th century BCE, Ugarit remained in regular contact with Egypt and Alashiya (Cyprus).[citation needed]

In the second millennium BCE, Ugarit's population was Amorite, and the Ugaritic language probably has a direct Amoritic origin.[3] The kingdom of Ugarit may have controlled about 2,000 km2 on average.[3]

During some of its history it would have been in close proximity to, if not directly within the Hittite Empire.

Destruction

The last Bronze Age king of Ugarit, Ammurapi (circa 1215 to 1180 BCE), was a contemporary of the last known Hittite king, Suppiluliuma II. The exact dates of his reign are unknown. However, a letter[5] by the king is preserved, in which Ammurapi stresses the seriousness of the crisis faced by many Near Eastern states due to attacks. Ammurapi pleads for assistance from the king of Alashiya, highlighting the desperate situation Ugarit faced:

My father, behold, the enemy's ships came (here); my cities(?) were burned, and they did evil things in my country. Does not my father know that all my troops and chariots(?) are in the Land of Hatti, and all my ships are in the Land of Lukka? ... Thus, the country is abandoned to itself. May my father know it: the seven ships of the enemy that came here inflicted much damage upon us.[6]

Eshuwara, the senior governor of Cyprus, responded:

As for the matter concerning those enemies: (it was) the people from your country (and) your own ships (who) did this! And (it was) the people from your country (who) committed these transgression(s)...I am writing to inform you and protect you. Be aware![7]

The ruler of Carchemish sent troops to assist Ugarit, but Ugarit had been sacked. A letter sent after Ugarit had been destroyed said:

When your messenger arrived, the army was humiliated and the city was sacked. Our food in the threshing floors was burnt and the vineyards were also destroyed. Our city is sacked. May you know it! May you know it![8]

By excavating the highest levels of the city's ruins, archaeologists can study various attributes of Ugaritic civilization just before their destruction, and compare artifacts with those of nearby cultures to help establish dates. Ugarit also contained many caches of cuneiform tablets, actual libraries that contained a wealth of information. The destruction levels of the ruin contained Late Helladic IIIB pottery ware, but no LH IIIC (see Mycenaean period). Therefore, the date of the destruction of Ugarit is important for the dating of the LH IIIC phase in mainland Greece. Since an Egyptian sword bearing the name of pharaoh Merneptah was found in the destruction levels, 1190 BCE was taken as the date for the beginning of the LH IIIC. A cuneiform tablet found in 1986 shows that Ugarit was destroyed after the death of Merneptah (1203 BCE). It is generally agreed that Ugarit had already been destroyed by the eighth year of Ramesses III (1178 BCE). Recent radiocarbon work, combined with other historical dates and the eclipse of January 21, 1192, indicates a destruction date between 1192 and 1190 BCE.[9]

Whether Ugarit was destroyed before or after Hattusa, the Hittite capital, is debated. The destruction was followed by a settlement hiatus. Many other Mediterranean cultures were deeply disordered just at the same time. Some of the disorder was apparently caused by invasions of the mysterious Sea Peoples.

Kings

| Ruler | Reigned | Comments |

|---|---|---|

| Niqmaddu I | Unknown | First known Ugaritan king, known only from a damaged seal that mentions "Yaqarum, son of Niqmaddu, king of Ugarit".[10] |

| Yaqarum | Unknown | Second known Ugaritan king, known only from a damaged seal that mentions "Yaqarum, son of Niqmaddu, king of Ugarit".[10] |

| Ammittamru I | c. 1350 BCE | |

| Niqmaddu II | c. 1350–1315 BCE | Contemporary of Suppiluliuma I of the Hittites |

| Arhalba | c. 1315–1313 BCE | Contemporary of king Mursili II of the Hittites |

| Niqmepa | c. 1313–1260 BCE | Treaty with Mursili II of the Hittites; Son of Niqmadu II |

| Ammittamru II | c. 1260–1235 BCE | Contemporary of Bentisina of Amurru; Son of Niqmepa |

| Ibiranu | c. 1235–1225/20 BCE | Addressee of the letter of Piha-walwi |

| Niqmaddu III | c. 1225/20 – 1215 BCE | |

| Ammurapi | c. 1200 BCE | Contemporary of Chancellor Bay of Egypt. Last known ruler of Ugarit. Ugarit is destroyed in his reign. |

Language and literature

| Ugarit |

|---|

|

| Places |

| Kings |

| Culture |

| Texts |

Alphabet

Scribes in Ugarit appear to have originated the "Ugaritic alphabet" around 1400 BCE: 30 letters, corresponding to sounds, were inscribed on clay tablets. Although they are cuneiform in appearance, the letters bear no relation to Mesopotamian cuneiform signs; instead, they appear to be somehow related to the Egyptian-derived Phoenician alphabet. While the letters show little or no formal similarity to the Phoenician, the standard letter order (seen in the Phoenician alphabet as ʔ, B, G, D, H, W, Z, Ḥ, Ṭ, Y, K, L, M, N, S, ʕ, P, Ṣ, Q, R, ʃ) shows strong similarities between the two, suggesting that the Phoenician and Ugaritic systems were not wholly independent inventions.[11]

Ugaritic language

The existence of the Ugaritic language is attested to in texts from the 14th through the 12th century BCE. Ugaritic is usually classified as a Northwest Semitic language and therefore related to Hebrew, Aramaic, and Phoenician, among others. Its grammatical features are highly similar to those found in Classical Arabic and Akkadian. It possesses two genders (masculine and feminine), three cases for nouns and adjectives (nominative, accusative, and genitive); three numbers: (singular, dual, and plural); and verb aspects similar to those found in other Northwest Semitic languages. The word order in Ugaritic is verb–subject–object, subject-object-verb (VSO)&(SOV); possessed–possessor (NG) (first element dependent on the function and second always in genitive case); and noun–adjective (NA) (both in the same case (i.e. congruent)).[12]

Ugaritic literature

Apart from royal correspondence with neighboring Bronze Age monarchs, Ugaritic literature from tablets found in the city's libraries include mythological texts written in a poetic narrative, letters, legal documents such as land transfers, a few international treaties, and a number of administrative lists. Fragments of several poetic works have been identified: the "Legend of Keret", the "Legend of Danel", the Ba'al tales that detail Baal-Hadad's conflicts with Yam and Mot, among other fragments.[13]

The discovery of the Ugaritic archives in 1929 has been of great significance to biblical scholarship, as these archives for the first time provided a detailed description of Canaanite religious beliefs, during the period directly preceding the Israelite settlement. These texts show significant parallels to Hebrew biblical literature, particularly in the areas of divine imagery and poetic form. Ugaritic poetry has many elements later found in Hebrew poetry: parallelisms, metres, and rhythms. The discoveries at Ugarit have led to a new appraisal of the Hebrew Bible as literature.[citation needed]

Religion

The important textual finds from the site shed a great deal of light upon the cultic life of the city.[14]

The foundations of the Bronze Age city Ugarit were divided into quarters. In the north-east quarter of the walled enclosure, the remains of three significant religious buildings were discovered, including two temples (of the gods Baal Hadad and Dagon) and a building referred to as the library or the high priest's house. Within these structures atop the acropolis numerous invaluable mythological texts were found. These texts have provided the basis for understanding of the Canaanite mythological world and religion. The Baal cycle represents Baal Hadad's destruction of Yam (the god of chaos and the sea), demonstrating the relationship of Canaanite chaoskampf with those of Mesopotamia and the Aegean: a warrior god rises up as the hero of the new pantheon to defeat chaos and bring order.

Archaeology

Discovery

After its destruction in the early 12th century BCE, Ugarit's location was forgotten until 1928 when a peasant accidentally opened an old tomb while ploughing a field. The discovered area was the necropolis of Ugarit located in the nearby seaport of Minet el-Beida. Excavations have since revealed a city with a prehistory reaching back to c. 6000 BCE.[15]

Site and palace

The site is a sixty-five foot high mound. Archaeologically, Ugarit is considered quintessentially Canaanite.[16] A brief investigation of a looted tomb at the necropolis of Minet el-Beida was conducted by Léon Albanèse in 1928, who then examined the main mound of Ras Shamra.[17] But in the next year scientific excavations of Tell Ras Shamra were commenced by archaeologist Claude Schaeffer from the Musée archéologique in Strasbourg.[18] Work continued under Schaeffer until 1970, with a break from 1940 to 1947 because of World War II.[19][20]

The excavations uncovered a royal palace of ninety rooms laid out around eight enclosed courtyards, and many ambitious private dwellings. Crowning the hill where the city was built were two main temples: one to Baal the "king", son of El, and one to Dagon, the chthonic god of fertility and wheat. 23 stelae were unearthed: nine stelae, including the famous Baal with Thunderbolt, near the Temple of Baal, four in the Temple of Dagon and ten more at scattered places around the city.[21]

Texts

On excavation of the site, several deposits of cuneiform clay tablets were found. These have proven to be of great historical significance.

See also

Notes

- ^ Sometimes written "Ras Shamrah"; Arabic: رأس شمرة, literally "Cape Fennel"). See [1].

- ^ Bahn, Paul (1997). Lost Cities: 50 Discoveries in World Archaeology. London: Barnes & Noble. pp. 98–99.

- ^ a b Pardee, Dennis. "Ugaritic", in The Ancient Languages of Syria-Palestine and Arabia (2008) (pp. 5–6). Roger D. Woodard, editor. Cambridge University Press, ISBN 0-521-68498-6, ISBN 978-0-521-68498-9 (262 pages).

- ^ a b Bretschneider, Joachim; Otto, Thierry (8 June 2011). "The Sea Peoples, from Cuneiform Tablets to Carbon Dating". PLOS ONE. 6 (6): 1–20. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0020232. ISSN 1932-6203. PMC 3110627. PMID 21687714.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Letter RS 18.147

- ^ Jean Nougaryol et al. (1968) Ugaritica V: 87–90 no. 24

- ^ Cline, Eric H. (2014). Translation of letter RS 20.18 in "1177 B.C.: The Year Civilization Collapsed". Princeton University Press. p. 151

- ^ Cline, p. 151

- ^ "The Sea Peoples, from Cuneiform Tablets to Carbon Dating." Kaniewski D, Van Campo E, Van Lerberghe K, Boiy T, Vansteenhuyse K, et al., PLoS ONE 6(6), 2011

- ^ a b Smith, Mark S. (1994). The Ugaritic Baal Cycle: Volume I, Introduction with text, translation and commentary of KTU 1.1-1.2. p. 90. ISBN 9789004099951.

- ^ [2] Dennis Pardee, "The Ugaritic Alphabetic Cuneiform Writing System in the Context of Other Alphabetic Systems", (in Studies in Ancient Oriental Civilization, vol. 60, pp. 181–200, Oriental Institute, 2007)

- ^ Stanislav Segert, A basic Grammar of the Ugaritic Language: with selected texts and glossary (1984) 1997.

- ^ Nick Wyatt. Religious texts from Ugarit, (1998) rev. ed 2002.

- ^ Gregorio Del Olmo Lete, Canaanite Religion: According to the Liturgical Texts of Ugarit, 2004.

- ^ Yon, Marguerite (2006). The City of Ugarit at Tell Ras Shamra. Singapore: Eisenbrauns. p. 15. ISBN 978-1-57506-029-3. Retrieved 16 May 2015.

- ^ Tubb, Jonathan N. (1998), "Canaanites" (British Museum People of the Past)

- ^ Léon Albanèse, "Note sur Ras Shamra", Syria, vol. 10, pp.16–21, 1929

- ^ Charles Virolleaud, "Les Inscriptions Cunéiformes de Ras Shamra", Syria, vol. 10, pp. 304–310, 1929; Claude F. A. Schaeffer, The Cuneiform Texts of Ras Shamra-Ugarit, 1939

- ^ Claude F. A. Schaeffer, The Cuneiform Texts of Ras Shamra-Ugarit: The Schweich Lectures of the British Academy 1937, Periodicals Service Co, 1986, ISBN 3-601-00536-0

- ^ Claude F. A. Schaeffer et al., Le Palais Royal D'Ugarit III: Textes Accadiens et Hourrites Des Archives Est, Ouest et Centrales, Two Volumes (Mission De Ras Shamra Tome VI), Imprimerie Nationale, 1955

- ^ Caubet, Annie. "Stela Depicting the Storm God Baal". Musée du Louvre. Retrieved 27 October 2012.

References

- internal strugle Annalee Newitz, What Happened to the Original 1 Percent?, New York Time, May 11, 2020

- Ugarit Forschungen (Neukirchen-Vluyn). UF-11 (1979) honors Claude Schaeffer, with about 100 articles in 900 pages. pp 95, ff, "Comparative Graphemic Analysis of Old Babylonian and Western Akkadian", ( i.e. Ugarit and Amarna (letters), three others, Mari, OB,Royal, OB,non-Royal letters). See above, in text.

- Bourdreuil, P. 1991. "Une bibliothèque au sud de la ville : Les textes de la 34e campagne (1973)". in Ras Shamra-Ougarit, 7 (Paris).

- Caquot, André & Sznycer, Maurice. Ugaritic Religion. Iconography of Religions, Section XV: Mesopotamia and the Near East; Fascicle 8; Institute of Religious Iconography, State University Groningen; Leiden: E.J. Brill, 1980.

- Drews, Robert. 1995. The End of the Bronze Age: Changes in Warfare and the Catastrophe ca. 1200 BC (Princeton University Press). ISBN 0-691-02591-6

- de Moor, Johannes C. The Seasonal Pattern in the Ugaritic Myth of Ba'lu, According to the Version of Ilimilku. Alter Orient und Altes Testament, Band 16. Neukirchen – Vluyn: Verlag Butzon & Berker Kevelaer, Neukirchener Verlag des Erziehungsvereins, 1971

- Gibson, J.C.L., originally edited by G.R. Driver. Canaanite Myths and Legends. Edinburgh: T. and T. Clark, Ltd., 1956, 1977.*K. Lawson and K. L. Younger Jr, "Ugarit at Seventy-Five," Eisenbrauns, 2007, ISBN 1-57506-143-0

- L'Heureux, Conrad E. Rank Among the Canaanite Gods: El, Ba'al, and the Repha'im. Harvard Semitic Museum, Harvard Semitic Monographs No. 21, Missoula MT: Scholars Press, 1979.

- Meletinskii, E. M., 2000 The Poetics of Myth

- Mullen, E. Theodore, Jr. The Assembly of the Gods: The Divine Council in Canaanite and Early Hebrew Literature. Harvard Semitic Museum, Harvard Semitic Monographs No. 24, Cambridge, MA: Harvard Press, 1980/ Atlanta, GA: Scholars Press Reprint, 1986. (comparison of Ugaritic and Old Testament literature).

- Dennis Pardee, Ritual and Cult at Ugarit, (Writings from the Ancient World), Society of Biblical Literature, 2002, ISBN 1-58983-026-1

- William M. Schniedewind, Joel H. Hunt, 2007. A primer on Ugaritic: language, culture, and literature ISBN 0-521-87933-7 p. 14.

- Smith, Mark S. The Ugaritic Baal Cycle: Volume 1. Introduction with Text, Translation and Commentary of KTU 1.1–1.2, (Vetus Testamentum Supplements series, volume 55; Leiden: Brill, 1994).

- _____. The Ugaritic Baal Cycle: Volume 2. Introduction with Text, Translation and Commentary of KTU 1.3–1.4, (Vetus Testament Supplement series, volume 114; Leiden: Brill, 2008). Co-authored with Wayne Pitard.

- Smith, Mark S., 2001. Untold Stories. The Bible and Ugaritic Studies in the Twentieth Century ISBN 1-56563-575-2 Chapter 1: "Beginnings: 1928–1945"

- Tubb, Jonathan N. (1998), Canaanites (British Museum People of the Past).

- Wyatt, Nicolas (1998): Religious texts from Ugarit: the worlds of Ilimilku and his colleagues, The Biblical Seminar, volume 53. Sheffield, England: Sheffield Academic Press, paperback, 500 pages.

External links

- Ugarit (Tell Shamra) 1999 application for UNESCO world heritage site

- RSTI. The Ras Shamra Tablet Inventory: an online catalog of inscribed objects from Ras Shamra-Ugarit produced at the Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago.

- The Ras Shamra Tablet Inventory Blog

- Ugarit - Ancient History Encyclopedia

- Ugarit and the Bible - Quartz Hill School of Theology

- The Edinburgh Ras Shamra project includes an introduction to the discovery of Ugarit.

- Le Royaume d'Ougarit (in French)

- Dennis Pardee, Ugarit Ritual texts – Oriental Institute

- Pictures from 2009

- Ugarit

- States and territories established in the 18th century BC

- States and territories disestablished in the 12th century BC

- Populated places established in the 6th millennium BC

- Populated places disestablished in the 2nd millennium BC

- 1928 archaeological discoveries

- Bronze Age sites in Syria

- Amarna letters locations

- Former populated places in Syria

- Neolithic sites in Syria

- Destroyed cities

- Late Bronze Age collapse