Battle of Westerplatte

| Battle of Westerplatte | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Invasion of Poland of World War II | |||||||

Schleswig-Holstein firing her guns, September 5 1939 | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

~3,400 1 battleship 2 torpedo boats 60 aircraft | 210–240 | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

|

50 killed ~150 wounded |

15 killed ~40 wounded 155-185 captured | ||||||

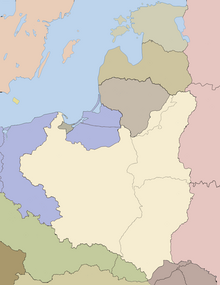

Location within Poland, 1939 borders | |||||||

The Battle of Westerplatte was one of the first battles in Germany's invasion of Poland, marking the start of World War II in Europe. Beginning on 1 September 1939, German army, naval and air forces and Danzig police assaulted Poland's Military Transit Depot (Wojskowa Składnica Tranzytowa, or WST) on the Westerplatte peninsula in the harbor of the Free City of Danzig. The Poles held out for seven days and repelled 13 assaults that included dive-bomber attacks and naval shelling.

Westerplatte's defense served as an inspiration for the Polish Army and people in the face of German advances elsewhere, and is still regarded as a symbol of resistance in modern Poland.

Background

Westerplatte is a peninsula in the Bay of Gdańsk.[1]: 646 Following the reestablishment of Polish independence after World War I, much of the surrounding region became part of Poland. However, the city of Danzig (present-day Gdańsk, Poland), historically an important port city, became an independent city-state, the Free City of Danzig. The Free City was nominally supervised by the League of Nations but, over time, Danzig became increasingly allied with Germany, reflecting its predominantly ethnic German population.[2]: 210 [3]: 21

In 1921, in the wake of the Polish-Soviet War, the League of Nations granted Poland the right to install a garrisoned ammunition depot near Gdańsk.[4]: 2684 Despite objections from the Free City, this right was confirmed in 1925, and an area of 60 hectares (600,000 m2) was selected on the Westerplatte peninsula.[4][5][6]: 443 Westerplatte was separated from the New Port of the Free City of Danzig mainly by the harbor channel; on land, the Polish-held part of Westerplatte was separated from Danzig's territory by a brick wall topped with barbed wire.[5]: 443 [6] A dedicated rail line, passing through the Free City, connected the depot with nearby Polish territory.[6]: 443 The depot, referred to in League documents as the Depot for Polish Munitions in Transit in the Port of Danzig[7]: 45 (Template:Lang-pl), was completed in November 1925, officially transferred to Poland on the last day of that year, and became operational shortly after in January 1926, with 22 active storage warehouses. The Polish garrison's complement was set at 88 soldiers (2 officers, 20 NCOs, and the rest privates), and Poland was prohibited construction of further military installations or fortifications on the site.[5][6]: 443–444

By early 1933, German politicians and media figures complained about the need for border adjustments. In addition, Polish and French discussed the need for a preventive war against Germany. On 6 March 1933, in what became known as the "Westerplatte incident" or "crisis", the Polish government landed a marine battalion on Westerplatte, briefly reinforcing the outpost to about 200 men, demonstrating Polish resolve to defend the outpost; more locally, the Polish maneuver was also intended to put pressure on the Danzig government, which was trying to renounce a prior agreement on shared Danzig-Polish control over the harbor police and to acquire full control of the police and the harbor.[8][9] The additional Polish troops were withdrawn on 16 March 1933, following protests from the League, Danzig, and Germany, but only in exchange for Danzig's withdrawal of its objections to the harbor-police agreement.[8]: 50 According to another source, on 14 March 1933 the League had authorized Poland to reinforce its garrison.[4]

Over subsequent years, the Poles constructed clandestine fortifications on Westerplatte.[5] These were not impressive: there were no bunkers or tunnels, only several small outposts (guardhouses), partially hidden in the peninsula's forest, and several more buildings in the peninsula's center, including barracks. Most buildings were constructed with reinforced concrete, and were supported by a network of field fortifications (trenches, barricades, and barbed wire).[5][10][11]: 54

Prelude

In March 1939, a German ultimatum to Lithuania led to Germany's annexation of the nearby Lithuanian coastal Klaipėda region; subsequently, the Westerplatte garrison was placed on alert.[5][6]: 445 Fearing a possible Nazi coup d'etat in Danzig, the Poles decided to secretly reinforce their garrison[5][6]: 445 and, for that purpose, resorted to a subterfuge: civilians in Polish Army uniform would leave the base, and new Polish soldiers would enter it.[6]: 445

By late August 1939, the Poles had reinforced their 88-man garrison, though its strength is still debated; older sources speak of 182 men, but more recent research suggests something in the range of 210 to 240, including six officers: Major Henryk Sucharski, Captain Franciszek Dąbrowski, Captain Mieczysław Słaby Lieutenant Leon Pająk, Lieutenant Stefan Ludwik Grodecki, and Second Lieutenant Zdzisław Kręgielski.[6]: 445 [12][13] Estimates include some 20 mobilized civilians and about 10 regular troops who happened to be on site when fighting began.[6]: 445 In addition to light arms (pistols, grenades, and about 160 rifles), weaponry included a 75 mm field gun wz. 1902/26, two antitank Bofors 37 mm guns, four 81 mm mortars, and about 40 machine guns, including 18 heavy ones.[6]: 446 [14] Field fortifications were extended: more trenches were dug, wooden barricades were built, barbed wire was strung into wire obstacles, and reinforced concrete shelters were built into the basements of the barracks. Foliage was thinned to reduce cover from expected avenues of attack.[5][6]: 446 [15]: 11–12

The Polish defense, which anticipated principally a German land-based assault, rested on three lines of defense. The outer line included entrenchments which were to hold long enough for the garrison to mobilize. The second line of defense centered on the six outposts. The final defense comprised the headquarters and barracks at the depot's center.[6]: 445 The plan called for Westerplatte to hold out for 12 hours, after which the siege was expected to be lifted by Polish reinforcements arriving from the mainland.[16]

On 25 August 1939 the German pre-dreadnought battleship Schleswig-Holstein, under the pretext of making a courtesy call, sailed into Danzig harbor,[6]: 446 anchoring 164 yards (150 m) from Westerplatte. On board was a Marinestosstruppkompanie (marine shock-troop company) with orders to launch an attack on Westerplatte on the morning of 26 August 1939. For their planned attack on Westerplatte, the Germans had an SS Heimwehr Danzig force of 1,500 men under Police General Friedrich-Georg Eberhardt, and the 225 marines under Lieutenant Wilhelm Henningsen. In overall command was Captain Gustav Kleikamp, aboard the Schleswig-Holstein. On 26 August he moved the battleship farther upstream. Major Sucharski, commanding Westerplatte, put his garrison on heightened alert.[15]: 12 Shortly before the German disembarkation, the orders were rescinded. Hitler had postponed hostilities on learning of the Polish-British Common Defence Pact, signed the day before, on 25 August 1939, and that Italy was hesitant about its obligations under the Pact of Steel.[17]: 18

Neither General Eberhardt nor Captain Kleikamp had specific information on the Polish defenses.[18] The Germans assumed that preliminary bombardment would soften up the fortifications enough for the marines to capture Westerplatte.[19]: 66 Reportedly Captain Kleikamp had been assured by the Danzig police that "Westerplatte would be taken in 10 minutes."[20]: 120 General Eberhardt himself was more cautious, estimating that "a few hours" would be needed to overcome the Polish garrison, which the Germans estimated at no more than 100 men.[16]

Battle

On the early morning of 1 September 1939, the Schleswig-Holstein suddenly fired a broadside at the Polish garrison. That salvo's time has been variously stated as 04:45, [21][22] 04:47,[23]: 5–6 or 04:48.[6]: 446 [24]: 8, 152 Polish historian Jarosław Tuliszka explains that 04:45 was the planned time, 04:47 was the time the order was given by Kleikamp and 04:48 was the time the guns actually fired.[24]: 152 Shortly after, on Westerplatte, Major Sucharski radioed the nearby Polish military base on the Hel Peninsula, "SOS: I'm under fire."[15]: 12

Eight minutes later Lieutenant Wilhelm Henningsen's marines from the Schleswig-Holstein advanced, expecting an easy victory over the Poles.[16] A Polish soldier, Staff Sergeant Wojciech Najsarek, was killed by machine-gun fire, the first combat casualty of the battle and perhaps of the war.[25][26]: 140 However, soon after crossing the artillery-breached brick wall, the Germans moved into an ambush. They found themselves in a kill zone of Polish crossfire from concealed firing positions (they believed they were also fired on by snipers in the trees, but that was not so), while barbed-wire entanglements impeded their movements. The Poles knocked out a German Schutzpolizei machine-gun nest, and Lt. Leon Pająk opened intense howitzer fire on the advancing Germans, who faltered and broke off their attack. The single 75 mm field gun fired 28 rounds, knocking out several machine-gun nests atop warehouses across the harbor canal, before it was destroyed by the battleship's guns.[15]: 12

At 06:22 the German marines frantically radioed the battleship that they had sustained heavy losses and were withdrawing. The Danzig police had tried to seize control of the harbor on the other side of Westerplatte, but had been defeated. Casualties were approximately 50 Germans and eight Poles, mostly wounded.[15]: 13 A longer bombardment from the battleship, lasting from 07:40 to 08:55, preceded a second attack.[16] The Germans tried again from 08:35 to 12:30[16] but encountered mines, felled trees, barbed wire and intense fire.[15]: 13 By noon the Germans retreated, Henningsen was gravely wounded.[16]

On the first day's combat, the Polish side had sustained four killed and several wounded.[6]: 446 The German marines had lost 16 killed and some 120 wounded.[16]

The German commanders concluded that a ground attack was not feasible until the Polish defenses had been softened up.[6]: 443 Re-examining aerial photographs, where they had previously underestimated the Polish defenses, they now overestimated them, concluding the Poles had constructed extensive underground and armored fortifications (six haystacks were declared to be armored bunker domes).[18][27] In the following days, the Germans bombarded the Westerplatte peninsula with naval and heavy field artillery, including a 105 mm howitzer battery and 210 mm mortars.[6]: 447 On 2 September, from 18:05 to 18:25,[16] a two-wave air raid by 60 Junkers Ju 87 Stuka dive bombers dropped 26.5 tons of bombs,[6]: 446 taking out the Polish mortars, destroying Outpost Five with a 500 kg bomb and killing at least eight Polish soldiers. The air raid shrouded all of Westerplatte in clouds of smoke and destroyed the Poles' only radio and much of their food supplies.[15]: 13 According to some German sources, after the air raid the Poles briefly displayed a white flag; but not all historians are convinced of this, and the German observers may have been mistaken.[13][16][18]

On 4 September, a German torpedo boat, the T196, supported by an old minesweeper, the Von der Gronen (formerly M107), made a surprise attack from the sea side.[28]: 3 The Poles' Wał post had been abandoned. Now only the Fort position prevented an attack from the north.[15]: 14 Though the Poles never landed a hit on the German naval units, the T196 and the Schleswig-Holstein suffered accidents due to crew error or equipment failure, with at least one fatalty and several injured men on the battleship.[18]

On 5 September Major Sucharski held a conference with his officers, during which he urged surrender: the post had only been supposed to hold out for twelve hours.[15]: 11, 14 His deputy, Captain Franciszek Dąbrowski, opposed surrender and the group decided to hold out a while longer.[15]: 14

Subsequently, the Poles repelled several cautious German probing attacks by the marines, Danzig SS, police and Wehrmacht. At 03:00 on 6 September, during one of the attacks, the Germans sent a burning train toward the land bridge, but the ploy failed when the terrified driver decoupled prematurely.[15]: 14 The train failed to reach the oil cistern; instead, it set fire to the woods, which had provided the Poles with valuable cover. In addition, the burning wagons created a perfect field of fire; the Germans suffered heavy losses. A second fire-train attack, in the afternoon, likewise failed.[15]: 15

At a second conference with his officers, on 6 September, Sucharski was again ready to surrender: the German Army was by now outside Warsaw, and Westerplatte was running critically low on supplies; moreover, many of the wounded were suffering from gangrene.[15]: 15 At 04:30 on 7 September the Germans opened intense fire on Westerplatte which lasted till 07:00. Flamethrowers and bombardment destroyed Outpost Two and damaged Outposts One and Four.[15]: 15 The Schleswig-Holstein took part in the bombardments.[6]: 447

At 09:45 on 7 September 1939 a white flag appeared. The Polish defense had so impressed the Germans that their commander, General Eberhardt, let Sucharski keep his ceremonial szabla (Polish saber) in captivity[6]: 447 (it was, however, confiscated later).[15]: 15 Contemporary English-language publications (such as Life and the Pictorial History of the War) misidentified the Polish commander as a Major "Koscianski".[29][30]

Sucharski surrendered the post to Captain Kleikamp, the Germans stood at attention as the Polish garrison marched out at 11:30.[15]: 15 Over 3,000 Germans (soldiers and support formations such as the Danzig police) had been tied up in the week-long operation against the small Polish garrison; about half of the Germans (570 on land, over 900 at sea) had taken part in direct action. German casualties totaled 50 killed (16 from the Kriegsmarine [16]) and 150 wounded.[6]: 447 The Poles had lost 15 men and had sustained at least 40 wounded.[6]: 447 [16]

Aftermath

On 8 September, the day after the capitulation, the Germans discovered a grave with the bodies of four unidentified Polish soldiers who had been executed by their comrades for attempted desertion. This had likely taken place following the 2 September air raids.[31]

Five days after the capitulation, on 12 September 1939, the Polish wireless operator, sergeant Kazimierz Rasiński, was murdered by the Germans. He was shot after brutal interrogation during which he refused to hand over radio codes.[32][33]: 55

On 19 September Adolf Hitler came to visit Gdańsk. While there, on 21 September, he inspected Westerplatte.[5]

Controversy surrounds the Polish garrison's commanding officer, Major Henryk Sucharski, and his executive officer, Captain Franciszek Dąbrowski. Early historiography considered Major Sucharski to have been in command throughout the battle, and consequently early accounts portrayed him as a heroic figure. More recent accounts from the early 1990s have presented evidence that Sucharski's officers had vowed not to disclose in their lifetimes that their commander had been shell-shocked for most of the battle and had advocated surrender as early as 2 September, and several times thereafter; and that Captain Dąbrowski had effectively taken command following Sucharski's breakdown on the second day of the siege.[27][34]: 153 [35][36] Sucharski's conduct is still debated by historians.[37]

Remembrance

The Battle of Westerplatte is often described as the opening battle of World War II,[21]: 1663 [22]: 19 but it was only one of many battles in the first phase of the German invasion of Poland known as the Battle of the Border. I. C. B. Dear described the Schleswig-Holstein's salvos as having occurred "minutes after Luftwaffe attacks on Polish airfields" and other targets.[38]: 995 A bridge in nearby Tczew had been bombed around 04:30 hours,[39]: 107 [40]: 4–7 and the false-flag Operation Himmler had begun hours earlier.[41]: 83

The Polish historian Krzysztof Komorowski writes that "Westerplatte has become one of the symbols of the Polish struggle for independence, and is inscribed in the list of the most heroic battles of modern Europe."[6]: 448

For both sides the battle had mostly political, rather than tactical, importance.[6]: 447 Still, it did tie up substantial German forces for much longer than anyone had expected, notably preventing the Schleswig-Holstein from lending fire support in the nearby battles of Hel and Gdynia.[6]: 448

Westerplatte's defense inspired the Polish Army and people even as German advances continued elsewhere; beginning 1 September 1939, Polish Radio repeatedly broadcast the phrase that made Westerplatte an important symbol: "Westerplatte broni się jeszcze" ("Westerplatte fights on").[34]: 39, 53 [42] On 16 September Konstanty Ildefons Gałczyński penned a poem, Pieśń o żołnierzach Westerplatte ("A Song of the Soldiers of Westerplatte"), voicing a subsequent myth that all of Westerplatte's defenders had died in the battle, fighting to the last man.[34]: 51, 158 [43]: 99 The battle became a symbol of resistance to the invasion – a Polish Thermopylae.[44]: 646 As early as 1943, a Polish People's Army unit was named for Westerplatte's soldiers (the Polish 1st Armoured Brigade of the Defenders of Westerplatte).[45] That same year the Polish Underground State named a street after Westerplatte; and the following year, during the 1944 Warsaw Uprising, an insurgent stronghold was named Westerplatte.[34]: 58

The Polish 75 mm field gun became one of Germany's first war trophies of World War II, displayed on a column at Flensburg. After the war it was moved to stand before the Naval Academy Mürwik.[16]

Westerplatte's Outposts One, Three and Four, the power plant, and the barracks survived the war.[10][34]: 294 In 1946 a Cemetery of the Defenders of Westerplatte and a Tomb of the Unknown Soldier were established on the peninsula; the cemetery was placed near the destroyed Outpost Five.[5][34]: 296 During the early postwar Stalinist era, Westerplatte was presented as a symbol of Poland's prewar anticommunist government and was marginalized in official history; Dr. Mieczysław Słaby, the garrison surgeon at Westerplatte, was arrested and tortured and died in the custody of the Ministry of Public Security in 1948.[10] After the mid-1950s liberalization, Westerplatte began to be used as a propaganda symbol; in 1956 the Polish Naval Academy was named for the "Heroes of Westerplatte", and that name began to be given to schools, streets, and other institutions.[5][34]: 298, 300 In 1962 a Christian cross at the cemetery was replaced with a Soviet T-34 tank, and the first government-organized remembrances began at Westerplatte.[10][34]: 302–304 In 1966 a Monument to the Defenders of the Coast, also known as the "Historical Monument, Site of the Battle of Westerplatte", a 25-meter-tall obelisk atop a mound, was erected at Westerplatte, set within a park, with smaller installations.[34]: 308–311 [46] Westerplatte became a popular tourist attraction.[34]: 351 Later Outpost One was relocated in order to save it from destruction in the construction of a new harbor channel.[5] In 1971 Major Sucharski's grave was relocated to Westerplatte from his original burial in Italy.[5][34]: 319–322 In 1974 a small museum was opened in the renovated Outpost One.[34]: 326 Since the 1980s Westerplatte has been administered by the National Museum in Gdańsk.[10] In 1981 the cross was restored to the cemetery.[5][34]: 334 In June 1987 Westerplatte was visited by Pope John Paul II;[34]: 338 [47] his visit is commemorated by a plaque unveiled in 2015.[48] A change symbolic of Poland's political transformation was the removal of the Soviet T-34 tank from the cemetery (in 2007 the tank was moved to a museum in another town).[5][34]: 349–350 In 2001 the Polish government recognized Westerplatte's ruins as an object of cultural heritage.[49] On 1 September 2003 the site was designated an official Historic Monument.[50] In the mid-2010s the Polish government decided to create a dedicated Westerplatte Museum, commemorating the 1939 battle; the museum is to open in 2019.[51]

Westerplatte is a common venue for remembrance ceremonies, usually held on 1 September, relating to World War II. They are generally attended by high-ranking Polish politicians such as Prime Minister Donald Tusk (2014),[52] President Bronisław Komorowski (2015),[53] President Andrzej Duda (2016),[54] and Prime Minister Beata Szydło (2017).[55] The commemoration of the 70th anniversary of the outbreak of World War II, in 2009, was attended by Prime Minister Tusk, former Prime Minister Tadeusz Mazowiecki, and former Presidents Lech Wałęsa and Aleksander Kwaśniewski, as well as by important figures from about 20 other countries, including German Chancellor Angela Merkel, Russian Prime Minister Vladimir Putin, Ukrainian Prime Minister Yulia Tymoshenko, and French Prime Minister François Fillon.[56]

The Battle of Westerplatte has been the subject of two Polish films: Westerplatte (1967), and Tajemnica Westerplatte (The Secret of Westerplatte, 2013).[57] It has also inspired dozens of books and scores of press articles, scholarly studies, and fictional works, as well as poems, songs, paintings, and other works of art.[34]: 3, 55

See also

References

- ^ Jerzy Jan Lerski; George J. Lerski; Halina T. Lerski (1996). Historical Dictionary of Poland, 966–1945. Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0-313-26007-0.

- ^ Matthew Parish (30 October 2009). Free City in the Balkans: Reconstructing a Divided Society in Bosnia. I.B.Tauris. ISBN 978-0-85771-273-8.

- ^ Gregory H . Fox (21 February 2008). Humanitarian Occupation. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-139-46973-9.

- ^ a b c Edmund Jan·Osma鈔czyk; Edmund Jan Osmańczyk; Rupert Lee (2003). Encyclopedia of the United Nations and International Agreements: T to Z. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 978-0-415-93924-9.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o Garba, Bartłomiej; Westphal, Marcin (2017-03-30). "Exhibition on Westerplatte". muzeum1939.pl. Museum of the Second World War. Retrieved 2018-06-04.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y Krzysztof Komorowski (2009). "Westerplatte (1–7 IX 1939)". Boje polskie 1939–1945: przewodnik encyklopedyczny. Bellona. ISBN 978-83-11-10357-3.

- ^ Report to the ... Assembly of the League on the Work of the Council, on the Work of the Secretariat and on the Measures Taken to Execute the Decisions of the Assembly. 1926.

- ^ a b Gerhard L. Weinberg (1 March 2010). Hitler's Foreign Policy 1933–1939: The Road to World War II. Enigma Books. ISBN 978-1-929631-91-9.

- ^ Crockett, Jameson W. (2009). "The Polish Blitz, More than a Mere Footnote to History: Poland and Preventive War with Germany, 1933". Diplomacy & Statecraft. 20 (4): 561–579. doi:10.1080/09592290903455667.

- ^ a b c d e Gierszewski, Andrzej (2018-04-30). "Wartownia Nr 1 Westerplatte" (in Polish). Muzeum Gdańska.

- ^ Steven J. Zaloga (19 August 2002). Poland 1939: The birth of Blitzkrieg. Bloomsbury USA. ISBN 978-1-84176-408-5.

- ^ Dróżdż, Krzysztof Henryk (2013). "Przyczynek do badań nad stanem liczbowym załogi Wojskowej Składnicy Tranzytowej na Westerplatte we wrześniu 1939 roku" [Addendum to the studies on the numbers of personnel the Westerplatte Military Depot in September 1939] (PDF). Przegląd Historyczno-Wojskowy (in Polish). 14(65)/2 (244): 196–200.

- ^ a b Jan, Szkudliński (2012). "Spór w sprawie białej flagi nad Westerplatte" [Debate regarding the white flag at Westerplatte] (PDF). Przegląd Historyczno-Wojskowy (in Polish). 13 (64)/4 (242): 153–163.

- ^ "Westerplatte". www.mhmg.pl. Muzeum Historyczne Miasta Gdańska. Archived from the original on 2018-06-12. Retrieved 2018-06-05.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p Parragon, Incorporated (2008). Great Battles of World War II. Parragon. ISBN 978-1-4075-2513-6.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Laskowski, Piotr (2008). "Kompania szturmowa Kriegsmarine w walkach na Westerplatte 1939 r" [Assault company of Kriegsmarine in the battle of Westerplatte in 1939] (PDF). Przegląd Morski (in Polish). 9: 55–63.

- ^ Janusz Piekałkiewicz (1987). Sea War, 1939–1945. Historical Times. ISBN 978-0-918678-17-1.

- ^ a b c d Szkudliński, Jan (2015). "Wojskowa składnica tranzytowa na Westerplatte w świetle nowych niemieckich materiałów archiwalnych" [Westerplatte Military Depot in light of the new German archival materials] (PDF). Przegląd Historyczno-Wojskowy (in Polish). 16 (67)/3 (253): 141–159.

- ^ David G. Williamson (2011). Poland Betrayed: The Nazi-Soviet Invasions of 1939. Stackpole Books. ISBN 978-0-8117-0828-9.

- ^ Richard Hargreaves (2010). Blitzkrieg Unleashed: The German Invasion of Poland, 1939. Stackpole Books. ISBN 978-0-8117-0724-4.

- ^ a b David T. Zabecki (1 May 2015). World War II in Europe: An Encyclopedia. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-135-81242-3.

The earliest fighting started at 0445 hours when marines from the battleship Schleswig-Holstein attempted to storm a small Polish fort in Danzig, the Westerplate

- ^ a b Lawrence Paterson (30 November 2015). Schnellboote: A Complete Operational History. Seaforth Publishing. ISBN 978-1-84832-083-3.

Two minutes later the old battleship Schleswig-Holstein opened World War Two by bombarding the Polish military transit depot at Westerplatte, Danzig

- ^ Williamson, Gordon (2003). German Battleships 1939–45. Oxford: Osprey Publishing. ISBN 978-1-84176-498-6.

- ^ a b Jarosław Tuliszka (2003). Westerplatte 1926–1939: dzieje Wojskowej Składnicy Tranzytowej w Wolnym Mieście Gdańsku. Wydawn. Adam Marszałek. ISBN 978-83-7322-504-6.

- ^ Teresa Masłowska (September 2007). "Wojenne drogi polskich kolejarzy" (PDF). Kurier PKP (in Polish). 2007 (35): 10.

Wojciech Najsarek był jedną z pierwszych ofiar II wojny światowej.

- ^ Andrzej Drzycimski (1990). Major Henryk Sucharski. Zakład Narodowy im. Ossolińskich. ISBN 978-83-04-03374-0.

st. sierż. Wojciech Najsarek, zawiadowca stacji, poległ jako pierwszy z żołnierzy Składnicy, na posterunku, na stacji PKP Westerplatte

- ^ a b Piński, Jan; Przedmojski, Rafał (2005-09-04). "Koniec mitu Westerplatte". WPROST.pl (in Polish). Retrieved 2018-07-06.

- ^ Rohwer, Jürgen; Hümmelchen, Gerhard (1992). Chronology of the War at Sea 1939–1945. London: Greenhill Books. ISBN 978-1-85367-117-3.

- ^ "Heroic Polish Defense of Westerplatte Ends as Nazi Mop-up of Poland Begins". Life. 9 October 1939. p. 30. ISSN 0024-3019.

- ^ Hutchinson, Walter (1939). Pictorial History of the War (Volume 1). Virtue and Company Ltd. p. 89.

- ^ Sudoł, Tomasz (2013). "Tajemnica Westerplatte" (PDF). Pamięć.pl (in Polish). 2: 14–15.

- ^ "Rasiński Kazimierz sierż rez". www.mhmg.pl. Muzeum Historyczne Miasta Gdańska. Archived from the original on 2018-06-21. Retrieved 2018-06-21.

- ^ Robert Jackson (2007). Battle of the Baltic: The Wars 1918–1945. Pen & Sword Maritime. ISBN 978-1-84415-422-7.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p Zajączkowski, Krzysztof (2013). Westerplatte. Mechanizmy kształtowania się i funkcjonowania miejsca pamięci w latach 1945–1989 [Westerplatte. Mechanisms of creation and functioning of places of memory in years 1945–1989] (PDF) (in Polish). Katowice: Uniwersytet Śląski w Katowicach (doctoral thesis).

- ^ Kwiatkowski, Mikołaj (2016-08-30). "Major Henryk Sucharski: wojskowy z tajemnicą". Histmag.org. Retrieved 2018-07-06.

- ^ Piotr Derdej (2009). Westerplatte, Oksywie, Hel 1939 (in Polish). Bellona. p. 8. GGKEY:XBT004NC99S.

- ^ Maciorowski, Mirosław (1 September 2014). "Tajemnica majora Sucharskiego". wyborcza.pl (in Polish). Retrieved 2018-07-06.

- ^ Ian Dear (1 January 1995). The Oxford guide to World War II. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-534096-9.

- ^ Steve Zaloga; W. Victor Madej (31 December 1990). The Polish Campaign, 1939. Hippocrene Books. ISBN 978-0-87052-013-6.

- ^ John Weal (20 October 2012). Bf 109D/E Aces 1939–41. Bloomsbury Publishing. ISBN 978-1-78200-526-1.

- ^ Anna M. Wittmann (5 December 2016). Talking Conflict: The Loaded Language of Genocide, Political Violence, Terrorism, and Warfare. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-1-4408-3425-7.

- ^ Cichocki, Paweł. "Kapitulacja Westerplatte - Muzeum Historii Polski". Muzeum Historii Polsk (in Polish). Retrieved 2018-06-21.

- ^ Kira Gałczyńska (1998). Gałczyński. Wydawn. Dolnośląskie. Retrieved 11 April 2011.

- ^ Jerzy Jan Lerski (1996). Historical dictionary of Poland, 966–1945. Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0-313-26007-0. Retrieved 11 April 2011.

- ^ Anduła, Kamil. "Udział 1 Warszawskiej Brygady Pancernej im. Bohaterów Westerplatte w walkach o Kępę Oksywską (30 marca-5 kwietnia 1945 r.)" [Participation of the Polish 1st Armoured Brigade of the Heroes of Westerplatte in the battle of Kępa Oksywska (30 March-5 April 1945)] (PDF). Przegląd Historyczno-Wojskowy (in Polish). 13 (64)/3 (241): 43–62.

- ^ ZDiZ. "1 Pomnik Historii "POLE BITWY NA WESTERPLATTE" : Gdański Zarząd Dróg i Zieleni". www.zdiz.gda.pl (in Polish). Retrieved 2018-07-06.

- ^ "12 czerwca 1987. Jan Paweł II na Westerplatte | Region Gdański NSZZ "Solidarność"Region Gdański NSZZ "Solidarność"". www.solidarnosc.gda.pl (in Polish). 2018-06-12. Retrieved 2018-07-08.

- ^ Oleksy, Ewelina (2015-06-13). "Tablica ze słowami papieża Jana Pawła II na Westerplatte [ZDJĘCIA]". gdansk.naszemiasto.pl (in Polish). Retrieved 2018-07-08.

- ^ Official listing of objects of cultural heritage, NID (National Heritage Board of Poland)

- ^ "Gdańsk – pole bitwy na Westerplatte". www.nid.pl. Narodowy Instytut Dziedzictwa. Retrieved 2018-06-21.

- ^ "Muzeum Westerplatte i Wojny 1939. Otwarcie 1 września 2019 roku". TVP (in Polish). 2016-01-23. Retrieved 2018-06-21.

- ^ "Westerplatte. Tusk jak nie Tusk: dziś nie "czas na piękne przemówienia"". Retrieved 2018-07-08.

- ^ "Komorowski na Westerplatte: w Europie są siły, które dążą do utrzymania sąsiadów w wasalnej zależności" (in Polish). Retrieved 2018-07-08.

- ^ "Nie można pozwolić na to, aby wracały w Europie działania i ambicje o charakterze imperialnym". TVN24.pl. Retrieved 2018-07-08.

- ^ ""Musimy przypominać, kto był bohaterem, a kto katem". Premier na Westerplatte w 78. rocznicę wybuchu II wojny światowej". WPROST.pl (in Polish). 2017-09-01. Retrieved 2018-07-08.

- ^ Sandecki, Maciej (2009-09-02). "Przesłanie z Westerplatte". wyborcza.pl (in Polish). Wyborcza.pl. Retrieved 2018-07-08.

- ^ Battle of Westerplatte at IMDb