Bowling Green (New York City)

Bowling Green Fence and Park | |

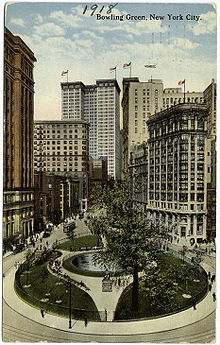

Bowling Green in a composite photograph taken from the steps of the U.S. Custom House looking north | |

| Location | Southern end of Broadway, New York City |

|---|---|

| Built | 1733 |

| NRHP reference No. | 80002673 |

| Added to NRHP | April 9, 1980[1] |

Bowling Green is a small public park in South Ferry, Manhattan at the end of Broadway, next to the site of the original Dutch fort of New Amsterdam. Built in 1733, originally including a bowling green, it is the oldest public park in New York City and is surrounded by its original 18th-century fence. At its northern end is the Charging Bull sculpture. Bowling Green Fence and Park is listed on the U.S. National Register of Historic Places. It is abutted by Battery Park to the west.

History

Colonial era

The park has long been a center of activity in the city going back to the days of New Amsterdam, when it served as a cattle market between 1638 and 1647, and parade ground. In 1675, the Common Council designated the "plaine afore the forte" for an annual market of "graine, cattle and other produce of the country". In 1677 the city's first public well was dug in front of Fort Amsterdam at Bowling Green.[2] In 1733, the Common Council leased a portion of the parade grounds to three prominent neighboring landlords for a peppercorn a year, upon their promise to create a park that would be "the delight of the Inhabitants of the City" and add to its "Beauty and Ornament"; the improvements were to include a "bowling green" with "walks therein".[3] The surrounding streets were not paved with cobblestones until 1744.

On August 21, 1770, the British government erected a 4,000 pound (1,800 kg) gilded lead equestrian statue of King George III in Bowling Green; the King was dressed in Roman garb in the style of the Equestrian Statue of Marcus Aurelius. The statue had been commissioned in 1766, along with a statue of William Pitt, from the prominent London sculptor Joseph Wilton, as a celebration of victory after the Seven Years' War. With the rapid deterioration of relations with the mother country after 1770, the statue became a magnet for the Bowling Green protests;[4] in 1773, the city passed an anti-graffiti and anti-desecration law to counter vandalism against the monument, and a protective cast-iron fence, which still stands,[5] was built along the perimeter of the park.

On July 9, 1776, after the Declaration of Independence was read to Washington's troops at the current site of City Hall, local Sons of Liberty rushed down Broadway to Bowling Green, where they toppled the statue of King George III. The fence post finials of cast-iron crowns on the protective fence were sawed off, with the saw marks still visible today.[5] The event is one of the most enduring images in the city's history. According to folklore, the statue was chopped up and shipped to a Connecticut foundry under the direction of Oliver Wolcott to be made into 42,088 patriot bullets at 20 bullets per pound (2,104.4 pounds). The statue's head was to have been paraded about town on pike-staffs, but was recovered by Loyalists and sent to England. Eight pieces of the lead statue are preserved in the New-York Historical Society;[6] one in the Museum of the City of New York as well as one in Connecticut [7] (estimated total of 260/270 pounds);[8] The event has been depicted over the years in several works of art, including an 1854 painting by William Walcutt, and an 1859 painting by Johannes Adam Simon Oertel.

Post-colonial era

The marble slab of the statue's pedestal was first used for a tombstone of a Major John Smith of the Black Watch who died in 1783; when Smith's grave site was leveled in 1804, the slab became a stone step at two successive mansions; in 1880 the inscription was rediscovered and the slab was transferred to the New-York Historical Society. The monument base can be seen in the background of the portrait of George Washington painted by John Trumbull in 1790, conserved in the City Hall. The William Pitt statue is in the New-York Historical Society.[9]

Following the Revolution, the remains of the fort facing Bowling Green were demolished in 1790 and part of the rubble used to extend Battery Park to the west. In its place a grand Government House was built, suitable, it was hoped, for a President's House, with a four-columned portico facing across Bowling Green and up Broadway. Governor John Jay later inhabited it. When the state capital was moved to Albany, the building served as a boarding house and then the custom house before being demolished in 1815.[10] Elegant townhouses were built around the park, which remained largely the private domain of the residents, though now some of the Tory patricians of New York were replaced by Republican ones; leading New York merchants, led by Abraham Kennedy, in a mansion at 1 Broadway that had a 56-foot facade under a central pediment[11] and a front towards the Battery Parade, as the new piece of open ground was called. The Hon. John Watts, whose summer place was Rose Hill; Chancellor Robert Livingston at no. 5, Stephen Whitney at no. 7, and John Stevens all constructed brick residences in Federal style facing Bowling Green.

The Alexander Macomb House, the second Presidential Mansion, stood north of the park at 39-41 Broadway. President George Washington occupied it from February 23 to August 30, 1790, before the U.S. capital moved to Philadelphia. By 1850, however, with the opening of Lafayette Street, then of Washington Square Park and Fifth Avenue, the general northward migration of residences in Manhattan led to the conversion of the residences into the shipping offices, resulting in full public access to the park.

The park suffered neglect after World War II, but was restored by the city in the 1970s and is now one of the most heavily traveled plazas in the city. The Bowling Green Fence and Park were listed on the U.S. National Register of Historic Places in 1980.[1]

20th and 21st centuries

In 1982, the Irish Institute of New York installed a plaque in Bowling Green park commemorating an important religious liberty challenge which occurred in Manhattan. Reverend Francis Makemie, the founder of American Presbyterianism, challenged the edict of Lord Cornbury by preaching at the home of William Jackson near by the Park. He was arrested in the Catholic colony and charged with preaching a "pernicious doctrine", but later acquitted.

In 1989, the sculpture Charging Bull by Arturo Di Modica was installed at the northern tip of the park by the New York City Department of Parks and Recreation after it had been confiscated by the police following its illegal installation on Wall Street. The sculpture has become one of the beloved and recognizable landmarks of the Financial District.[12][13]

The pool and fountain in the park were temporarily modified when the park was used as a filming location for The Sorcerer's Apprentice in early June 2009. Between shoots, equipment was stored in the park and on nearby streets.

In 2012, Occupy Wall Street Paraded around the bull on the first day of occupation.

Description and surroundings

The park is a teardrop-shaped plaza formed by the branching of Broadway as it nears Whitehall Street. The park is a fenced-in grassy area with benches that are popular lunchtime destinations for workers in the nearby Financial District. There is a fountain in the center.[citation needed]

The south end of the plaza is bounded by the front entrance of Alexander Hamilton U.S. Custom House,[14] which houses the George Gustav Heye Center for the Smithsonian Institution's National Museum of the American Indian[15] and the United States Bankruptcy Court for the Southern District of New York (Manhattan Division). Previously there was a public street along the south edge of the park, also called "Bowling Green", but since this area was needed for a modern entrance to the park's eponymous subway station, the road was eliminated and paved over with cobblestones. The New York City Subway station on the IRT Lexington Avenue Line, opened in 1905 and serving the 4 and 5 trains, is located under the plaza. Entrances dating from both 1905 and more recent renovations are located in and near the plaza.[16]

The urbanistic value of the space is created by the skyscrapers and other structures that surround it (listed clockwise):

- Alexander Hamilton US Custom House to the south

- Bowling Green Building, 11 Broadway (1895–98, W. and G. Audsley, later serving the White Star Line)

- Cunard Building, 25 Broadway (1921, Benjamin Wistar Morris, with Carrère and Hastings)[17]

- 1 Broadway, the United States Lines-Panama Pacific Line Building

- 2 Broadway (1959–60, Emery Roth & Sons, resurfaced in 1999 Skidmore, Owings & Merrill), a Modernist glass wall that replaced the distinguished Produce Exchange Building (1881–84, George B. Post), as an "acceptable sacrifice"[18] intended to spur financial district rebuilding

- 26 Broadway, the Standard Oil Company Building, on the east side of Broadway, facing the Cunard building (1922, Carrère and Hastings with Shreve, Lamb & Blake)

Charging Bull, a 3,200-kilogram (7,100 lb) bronze sculpture in Bowling Green, designed by Arturo Di Modica, stands 11 feet (3.4 m) tall[13] and measures 16 feet (4.9 m) long.[12] The oversize sculpture depicts a bull, the symbol of aggressive financial optimism and prosperity, leaning back on its haunches and with its head lowered as if ready to charge. The sculpture is a popular tourist destination drawing thousands of people a day, as well as "one of the most iconic images of New York"[19] and a "Wall Street icon"[20] symbolizing "Wall Street" and the Financial District.

References

- ^ a b "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service. April 15, 2008.

- ^ NYC Department of Environmental Protection, "New York City's Water Supply System: History".

- ^ Edwin G. Burrows and Mike Wallace, Gotham.

- ^ On 1 November 1765 the Sons of Liberty protesting the Stamp Act had marched down Broadway, carrying an effigy of the Royal Governor. They threw rocks and bricks at the adjacent Fort George, and at Bowling Green they burned the Governor's effigy as well as his coach, which had fallen into their hands.

- ^ a b "Permanent Revolution". New York magazine. Sep 10, 2012.

{{cite news}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ NYHS

- ^ "10 Museum of Connecticut History Fun Facts". Museumofcthistory.org. Retrieved 2014-06-05.

- ^ Five other pieces are reported to have survived but have been missing since 1777; 1829; 1864 {An 1867 account claims this piece was destroyed} see pp.431-432 at this NY Times article; 1894 see this NY Times article.

- ^ 1920 reference

- ^ Eric Homberger, Mrs. Astor's New York: Money and Social Power in a Gilded Age 2004:68

- ^ It is illustrated in a lithograph of Bowling Green, Homberger 2004, pl. 14.

- ^ a b D. McFadden, Robert (1989-12-16). "SoHo Gift to Wall St.: A 3½-Ton Bronze Bull". New York Times. Retrieved 2007-10-01.

- ^ a b Dunlap, David W. "The Bronze Bull Is for Sale, but There Are a Few Conditions", article, The New York Times, December 21, 2004, retrieved June 13, 2009

- ^ "United States Custom House (New York)". National Historic Landmark summary listing. National Park Service. 2007-09-13.

- ^ "National Museum of the American Indian". NY.com. Retrieved April 26, 2011.

{{cite web}}: External link in|publisher= - ^ "Station: Bowling Green (IRT East Side Line)". www.nycsubway.org. Retrieved 2014-06-05.

- ^ "This 'Renaissance' facade and its neighbors handsomely surround Bowling Green with a high order of group architecture", the AIA Guide to New York remarked at the height of Modernism, in 1968

- ^ Nycarchiture.com : Two Broadway

- ^ Pinto Nick, "Bull!", article, September 1, 2007, The Tribeca Trib, retrieved June 13, 2009

- ^ Greenfield, Beth and Robert Reid, Ginger Adams Otis, New York City, p 120, publisher: Lonely Planet, 2006, ISBN 1-74059-798-2, ISBN 978-1-74059-798-2 retrieved via Google Books on June 13, 2009

External links

![]() Media related to Bowling Green (New York City) at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Bowling Green (New York City) at Wikimedia Commons