California wine

California wine is wine made in the U.S. state of California, it supplies a vast majority of the American wine production, along with New Mexico wine these American wine regions are longtime examples of viticulture within New World wine. Almost three quarters the size of France, California accounts for nearly 90 percent of production[citation needed], the production of wine in California is one third larger than that of Australia. If California were a separate country, it would be the world's fourth largest wine producer.[2]

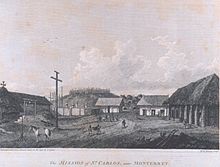

The state's viticultural history dates back to the 18th century when Spanish missionaries planted the first vineyards to produce wine for Mass.

Today there are more than 1,200 wineries in the state, ranging from small boutique wineries to large corporations with distribution around the globe.[3]

History

The state of California was first introduced to Vitis vinifera vines, a species of wine grapes native to the Mediterranean region, in the 18th century by the Spanish, who planted vineyards with each mission they established. The wine was used for religious sacraments as well as for daily life. The vine cuttings used to start the vineyards came from Mexico and were the descendant of the "common black grape" (as it was known) brought to the New World by Hernán Cortés in 1520. The grape's association with the church caused it to become known as the Mission grape, which was to become the dominant grape variety in California until the 20th century.[3]

The California Gold Rush in the mid-19th century brought waves of new settlers to the region, increasing the population and local demand for wine. The newly growing wine industry took hold in Northern California around the counties of Sonoma and Napa. The first commercial winery in California, Buena Vista Winery, was founded in 1857 by Agoston Haraszthy and is located in Sonoma, California. John Patchett opened the first commercial winery in the area that is now Napa County in 1859.[4] During this period some of California's oldest wineries were founded including Buena Vista Winery, Gundlach Bundschu, Inglenook Winery, Markham Vineyards and Schramsberg Vineyards. Chinese immigrants played a prominent role in the developing the Californian wine industry during this period - building wineries, planting vineyards, digging the underground cellars and harvesting grapes. Some even assisted as winemakers prior to the passing of the Chinese Exclusion Act which severely affected the Chinese community in favor of encouraging "white labor." By 1890, most of the Chinese workers were out of the wine industry.[3]

Phylloxera and Prohibition

The late 19th century also saw the advent of the phylloxera epidemic, a type of parasite similar to aphids, which had already ravaged France and other European vineyards. Vineyards were destroyed and many smaller operations went out of business. However, the remedy of grafting resistant American rootstock was well known, and the Californian wine industry was able to quickly rebound, and utilizing the opportunity to expand the plantings of new grape varieties. By the turn of the 20th century nearly 300 grape varieties were being grown in the state, supplying its nearly 800 wineries.

Worldwide recognition seemed imminent until January 16, 1919 when the 18th Amendment ushered in the beginning of Prohibition. Vineyards were ordered to be uprooted and cellars were destroyed. Some vineyards and wineries were able to survive by converting to table grape or grape juice production. A few more were able to stay in operation in order to continue to provide churches sacramental wine, an allowed exception to the Prohibition laws. However, most went out of business. By the time that Prohibition was repealed in 1933, only 140 wineries were still in operation.[3]

Modern era

It took time for the Californian wine industry to recover from this setback. By the 1960s, California was primarily known for its sweet port-style wines made from Carignan and Thompson Seedless grapes. However a new wave of winemakers soon emerged and helped usher in a renaissance period in California wine with a focus on new winemaking technologies and emphasizing quality. Several well-known wineries were founded in this decade including Robert Mondavi, Heitz Wine Cellars and David Bruce Winery (Santa Cruz Mountains). As the quality of Californian wine improved, the region started to receive more international attention. A watershed moment for the industry occurred in 1976 when British wine merchant Steven Spurrier invited several Californian wineries to participate in a blind tasting event in Paris. It was to compare the best of California with the best of Bordeaux and Burgundy - two famous French wine regions. In an event known as The Judgment of Paris, Californian wines shocked the world by sweeping the wine competition in both the red and white wine categories. Throughout the wine world, perspectives about the potential of California wines started to change. The state's wine industry continued to grow as California emerged as one of the world's premier wine regions.[3]

In 2010, it was reported for the first time in 16 years that California wine sales were down. This was not due to a decrease in drinking wine as much as it was a decrease in customers' willingness to spend top dollar on wine. Jon Fredrikson, President of Gomberg, Fredrikson & Associates said that sales of $3 to $6 a bottle wine and $9 to $12 wine had seen growth, but the sales of wine over $20 had stagnated. In addition, most of this loss in market was occurring in overseas sales, as opposed to U.S. sales.[5]

Climate and geography

California is a very geologically diverse region and varies greatly in the range of climates and terroirs that can be found. Most of the state's wine regions are found between the Pacific coast and the Central Valley. The Pacific Ocean and large bays, like San Francisco Bay, serve as tempering influences to the wine regions nearby providing cool winds and fog that balance the heat and sunshine.[3] While drought can be a vinicultural hazard, most areas of California receive sufficient amounts of rainfall with the annual rainfall of wine regions north of San Francisco between 24-45 inches (615–1150 mm) and the more southern regions receiving 13-20 inches. Winters are mild with little threat of frost damage though springtime. To curb the threat of frost, vineyard owners will often employ the use of wind machines, sprinklers and smudge pots to protect the vines.[6]

While California's wine regions can be generally classified as a Mediterranean climate, there are also regions with more continental dry climates. Proximity to the Pacific or bays as well as unobstructed access to the cool currents that come off them dictate the relative coolness of the wine region. Areas surrounded by mountain barriers, like some parts of Sonoma and Napa counties will be warmer due to the lack of this cooling influence. The soil types and landforms of California vary greatly, having been influenced by the plate tectonics of the North American and Pacific Plates. In some areas the soils can be so diverse that vineyards will establish blocks of the same vine variety planted on different soils for purpose of identifying different blending components. This diversity is one of the reasons why California has so many different and distinct American Viticultural Areas.[6]

Water and irrigation

The average vineyard in California uses 318 gallons of water to produce a single gallon of wine through irrigation. The average depends, in part, on the region where the grapes are grown, with 243 gallons of water per wine gallon in the North Coast region to 471 gallons per on the Central Coast.[7]

Wine regions

California has over 427,000 acres (1,730 km2) planted under vines mostly located in a stretch of land covering over 700 miles (1,100 km) from Mendocino County to the southwestern tip of Riverside County. There are over 107 American Viticultural Areas (AVAs), including the well-known Napa, Russian River Valley, Rutherford and Sonoma Valley AVAs. The Central Valley is California's largest wine region stretching for 300 miles (480 km) from the Sacramento Valley south to the San Joaquin Valley. This one region produces nearly 75% of all California wine grapes and includes many of California's bulk, box and jug wine producers like Gallo, Franzia and Bronco Wine Company.[3]

The wine regions of California are often divided into 4 main regions:[8]

- North Coast - Includes most of North Coast, California, north of San Francisco Bay. The large North Coast AVA covers most of the region. Notable wine regions include Napa Valley and Sonoma County and the smaller sub AVAs within them. Mendocino and Lake County are also part of this region.

- Central Coast - Includes most of the Central Coast of California and the area south and west of San Francisco Bay down to Santa Barbara County. The large Central Coast AVA covers the region. Notable wine regions in this area include Santa Clara Valley AVA, Santa Cruz Mountains AVA, San Lucas AVA, Paso Robles AVA, Santa Maria Valley AVA, Santa Ynez Valley AVA, Edna Valley AVA, Arroyo Grande Valley AVA, Livermore Valley AVA, Cienega Valley AVA and San Benito AVA.

- South Coast - Includes portion of Southern California, namely the coastal regions south of Los Angeles down to the border with Mexico. Notable wine regions in this area include Temecula Valley AVA, Antelope Valley/Leona Valley AVA, San Pasqual Valley AVA and Ramona Valley AVA. Also, wineries in the San Luis Rey Valley are in the process of creating a new AVA specific to that area.

- Central Valley - Includes California's Central Valley and the Sierra Foothills AVA. Notable wine regions in this area include the Lodi AVA.

Grapes and wines

Over one hundred grape varieties are grown in California including French, Italian and Spanish as well as hybrid grapes and new vitis vinifera varieties developed at the UC Davis Department of Viticulture and Enology. The seven leading grape varieties are:[3]

Other important red wine grapes include Barbera, Cabernet Franc, Carignan, Grenache, Malbec, Mourvèdre, Petite Sirah, Petit Verdot, Sangiovese, and Tannat. Important white wine varietals include Chenin blanc, French Colombard, Gewürztraminer, Marsanne, Muscat Canelli, Pinot blanc, Pinot gris, Riesling, Roussane, Sémillon, Trousseau gris, and Viognier.[9]

Up until the late 1980s, the Californian wine industry was dominated by the Bordeaux varietals and Chardonnay. Sales began to drop as wine drinkers grew bored[citation needed] with the familiarity of these wines. Groups of winemakers like Rhône Rangers and a new wave of Italian winemakers dubbed "Cal-Ital" reinvigorated the industry with new wine styles made from different varieties like Syrah, Viognier, Sangiovese and Pinot grigio. The Santa Cruz-based Bonny Doon Vineyard was one of the first wineries to promote these grape varieties in California actively. The large variety of wine grapes also encourages a large variety of wines. California produces wines made in nearly every single known wine style including sparkling, dessert and fortified wines.[3] In the early 21st century, vintners have begun reviving heirloom grape varieties, such as Trousseau gris and Valdiguié.[10]

New World wine styles

While Californian winemakers do craft wines in more "Old World" or European wine styles, most Californian wines favor simpler, more fruit dominant New World wines. The reliably warm weather allows many wineries to use very ripe fruit which creates a more fruit forward rather than earthy or mineralic style of wine. It also creates the opportunity for higher alcohol levels with many Californian wines having over 13.5 percent alcohol content. The style of Californian Chardonnay differs greatly from wines like Chablis with Californian winemakers frequently using malolactic fermentation and oak aging to make buttery, full bodied wines.[3] Californian Sauvignon blancs are not as herbaceous as wines from the Loire Valley or New Zealand and are more acidic. Some Sauvignon blanc are given time in oak which can dramatically change the profile of the wine. Robert Mondavi first pioneered this style as a Fume blanc which other Californian winemakers have adopted. However, that style is not strictly defined to mean an oak wine.[9]

The style of California Cabernet Sauvignon that first put California on the world's wine map at the Judgment of Paris is still a trademark style today. The wines are known for their concentration of fruits which produces lush, rich wines. Merlot became widely planted in the 1990s due to its wide popularity, and is still the highest selling of all varietal wines in the country. Many sites that were ill-suited for the grape began to produce harsh, characterless wines trying to model Cabernet. Merlot, when planted on better sites tend to produce a plush, concentrated style. The profile of Californian Pinot noir generally takes on a more intense, fruity style than the subtler, more elegant wines of Burgundy or Oregon. Until being passed up by Cabernet in 1998, Zinfandel was the most widely planted red wine grape in California. This was due in part to the wide popularity of White Zinfandel. Despite being made from the same grape, the only similarity between White and Red Zinfandel is the name. Zinfandel is a powerful, fruity wine with high levels of acidity and a jam-type flavor. White Zinfandel is a thin, slightly sweet blush wine. While the grape does have European origins, Zinfandel is considered a unique American style grape.[9]

Sparkling and dessert wines

California sparkling wine traces its roots to Sonoma in the 1880s with the founding of Korbel Champagne Cellars. The Korbel brothers made sparkling wine according to the méthode champenoise from Riesling, Chasselas, Muscatel and Traminer. Today most California sparkling wine is largely made from the same grapes used in Champagne: Chardonnay, Pinot noir and some Pinot Meunier. Some wineries will also use Pinot blanc, Chenin blanc and French Colombard. The premium quality producers still use the méthode champenoise (or traditional method) while some low cost producers, like Gallo's Andre brand or Constellation Brands' Cook's, will use the Charmat method.[11]

The potential for quality sparkling wine has attracted Champagne houses to open up wineries in California. These include Moët et Chandon's Domaine Chandon, Taittinger's Domaine Carneros and Louis Roederer's Roederer Estate. Despite being made with mostly the same grapes and with the same production techniques, California sparkling wines do not set out to be imitators of Champagne but rather to forge their own distinctive style. Instead of having the "biscuity", yeasty quality that distinguishes most high quality Champagnes, premium California sparkling wines show clarity of fruit flavors without being heavily "fruity". The wines strive for finesse and elegance. The optimal climate condition allows most sparkling wine producers to make a vintage dated wine every year while in Champagne this would only happen in exceptional years.[11]

Since the wine renaissance of the 1960s, the quality of California's dessert and fortified wines have been dramatically improved. Beringer was one of the first to create a botrytized wine from Sauvignon blanc and Sémillon. Though unlike in Sauternes, Beringer's wine was made of grapes regularly harvested and then introduced at the winery to Botrytis cinerea spores created in a laboratory. Since then California winemakers in places like the Anderson Valley AVA have found vineyards where this noble rot can occur naturally on the grapes. The Anderson and Alexander Valley AVAs have also developed a reputation for their Late Harvest wines made from Riesling. Several French and Italian style Muscat wines are produced throughout California and are known for their intense aromatics and balanced acidity. The port-style wines in California are often made from the traditional Portuguese wine grapes like Touriga Nacional, Tinta Cão and Tinta Roriz. Some uniquely Californian styles are also made from Zinfandel and Petite Sirah.[11]

See also

- Wine Country (California)

- Wine Institute (California)

- California Association of Winegrape Growers

- California Department of Alcoholic Beverage Control

- Agriculture in California

References

- ^ a b c "California: Appellation Profile". Appellation America. 2007. Archived from the original on October 17, 2015. Retrieved November 16, 2007.

- ^ Stevenson, Tom (2007). Sotheby's Wine Encyclopedia (4 ed.). Dorling Kindersley. p. 462. ISBN 978-0-7566-3164-2.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j MacNeil, Karen (2001). The Wine Bible. Workman Publishing. pp. 636–643. ISBN 978-1-56305-434-1.

- ^ Brennen, Nancy (November 21, 2010). "John Patchett: Introducing one of Napa's pioneers". Napa Valley Register. Napa, CA: Lee Enterprises, Inc. Retrieved September 30, 2011.

{{cite news}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ Bonne, Jon (January 29, 2010). "Why California wines aren't selling". SFGate.com.

- ^ a b Robinson, Jancis, ed. (2006). The Oxford Companion to Wine (3 ed.). Oxford University Press. pp. 126–127. ISBN 978-0-19-860990-2.

- ^ Heller, Marc (2019-07-25). "Water shortages force a reckoning in Calif. wine country". E&E News. Environment & Energy Publishing, LLC. Retrieved 2019-07-29.

- ^ Stevenson, Tom (2007). Sotheby's Wine Encyclopedia (4 ed.). Dorling Kindersley. pp. 469–473. ISBN 978-0-7566-3164-2.

- ^ a b c MacNeil, Karen (2001). The Wine Bible. Workman Publishing. pp. 644–651. ISBN 978-1-56305-434-1.

- ^ van der Vink, Julia (July 23, 2013). "California wine gets back to its roots". CNN. Archived from the original on February 2, 2017. Retrieved July 27, 2013.

{{cite news}}:|archive-date=/|archive-url=timestamp mismatch; February 16, 2014 suggested (help) - ^ a b c MacNeil, Karen (2001). The Wine Bible. Workman Publishing. pp. 652–657. ISBN 978-1-56305-434-1.

External links

- Template:Dmoz

- DiscoverCaliforniaWine.com - The Wine Institute's consumer site

- WineFiles.org - publicly searchable archives of the Sonoma County wine library