Cantonese opera

| Cantonese opera | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 1. 粵劇 2. 大戲 | ||||||||||

| |||||||||||

| This article is part of the series on |

| Cantonese culture |

|---|

The Cantonese opera (Chinese: 粵劇) is one of the major categories in Chinese opera, originating in southern China's Guangdong Province. It is popular in Guangdong, Guangxi, Hong Kong, Macau and among the Chinese community in Southeast Asia. Like all versions of Chinese opera, it is a traditional Chinese art form, involving music, singing, martial arts, acrobatics, and acting.

History

There is a debate about the origins of Cantonese opera, but it is generally accepted that opera was brought from the northern part of China and slowly migrated to the southern province of Guangdong in late 13th century, during the late Southern Song dynasty. In the 12th century, there was a theatrical form called the Nanxi or "Southern drama", which was performed in public theatres of Hangzhou, then capital of the Southern Song. With the invasion of the Mongol army, Emperor Gong of the Song dynasty fled with hundreds of thousands of Song people into Guangdong in 1276. Among them were Nanxi performers from Zhejiang, who brought Nanxi into Guangdong and helped develop the opera traditions in the south.

Many well-known operas performed today, such as Tai Nui Fa originated in the Ming Dynasty and The Purple Hairpin originated in the Yuan Dynasty, with the lyrics and scripts in Cantonese. Until the 20th century all the female roles were performed by males.

Development in Hong Kong

Beginning in the 1950s massive waves of immigrants fled Shanghai to destinations like North Point.[1] Their arrival boosted the Cantonese opera fan-base significantly. However, a decreased number of Cantonese opera troupes are left to preserve the art in Hong Kong today. As a result, many stages that were dedicated to the Cantonese genre are closing down. Hong Kong's Sunbeam Theatre is one of the last facilities that is still standing to exhibit Cantonese opera.

To intensify education in Cantonese opera, the Cantonese Artists Association of Hong Kong started to run an evening part-time certificate course in Cantonese opera training with assistance from The Hong Kong Academy for Performing Arts in 1998. In 1999, the Association and the Academy further conducted a two-year daytime diploma programme in performing arts in Cantonese opera in order to train professional actors and actresses. Aiming at further raising the students' level, the Association and the Academy launched an advanced course in Cantonese opera in the next academic year.

In recent years, the Hong Kong Arts Development Council has given grants to Love and Faith Cantonese Opera Laboratory to conduct Cantonese opera classes for children and youths. The Leisure and Cultural Services Department has also funded the International Association of Theatre Critics (Hong Kong Branch) to implement the "Cultural Envoy Scheme for Cantonese Opera" for promoting traditional Chinese productions in the community.

Characteristics

Cantonese opera shares many common characteristics with other Chinese theatre genres. Commentators often take pride in the idea that all Chinese theatre styles are similar but with minor variations on the pan-Chinese music-theatre tradition and the basic features or principles are consistent from one local performance form to another. Thus, music, singing, martial arts, acrobatics and acting are all featured in Cantonese opera. Most of the plots are based on Chinese history and famous Chinese classics and myths. Also, the culture and philosophies of the Chinese people can be seen in the plays. Virtues (like loyalty, love, patriotism and faithfulness) are often reflected by the operas.

Some particular features of Cantonese opera are:

- Cing sik sing (程式性; Jyutping: cing4 sik1 sing3) – formulaic, formalised.

- Heoi ji sing (虛擬性; Jyutping: heoi1 ji5 sing3) – abstraction of reality, distancing from reality.

- Sin ming sing (鮮明性; Jyutping: sin1 ming4 sing3) – clear-cut, distinct, unambiguous, well-defined.

- Zung hap ngai seot jing sik (綜合藝術形式; Jyutping: zung3 hap6 ngai6 seot6 jing4 sik1) – a composite or synthetic art form.

- Sei gung ng faat (四功五法; Pinyin: sì gōng wǔ fǎ, Jyutping: sei3 gung1 ng5 faat3) – the four skills and the five methods.

The four skills and five methods are a simple codification of training areas that theatre performers must master and a metaphor for the most well-rounded and thoroughly-trained performers. The four skills apply to the whole spectrum of vocal and dramatic training: singing, acting/movements, speech delivery, and martial/gymnastic skills; while the five methods are categories of techniques associated with specific body parts: hands, eyes, body, hair, and feet/walking techniques.

Significance

Before widespread formal education, Cantonese opera taught morals and messages to its audiences rather than being solely entertainment. The government used theatre to promote the idea of be loyal to the emperor and love the country (忠君愛國). Thus, the government examined the theatre frequently and would ban any theatre if a harmful message was conveyed or considered. The research conducted by Lo showed that Cantonese Operatic Singing also relates older people to a sense of collectivism, thereby contributing to the maintenance of interpersonal relationships and promoting successful ageing. (Lo, 2014).[2] Young people construct the rituals of learning Cantonese opera as an important context for their personal development.[3]

Performers and roles

Types of play

There are two types of Cantonese opera plays: Mou (武, "martial arts") and Man (文, "highly educated", esp. in poetry and culture). Mou plays emphasize war, the characters usually being generals or warriors. These works contain action scenes and involve a lot of weaponry and armour. Man plays tend to be gentler and more elegant. Scholars are the main characters in these plays. Water sleeves (see Frequently Used Terms) are used extensively in man plays to produce movements reflecting the elegance and tenderness of the characters; all female characters wear them. In man plays, characters put a lot of effort into creating distinctive facial expressions and gestures to express their underlying emotions.

Roles

There are four types of roles: Sang, Daan, Zing, and Cau.

Sang (生)

These are male roles in Cantonese opera. As in other Chinese operas, there are different types of male roles, such as:

- Siu2 Sang1 (小生) – Literally, young gentleman, this role is known as a young scholar.

- Mou5 Sang1 (武生) – Male warrior role.

- Siu2 Mou5 Sang1 (小武生) – Young Warrior (usually not lead actor but a more acrobatic role).

- Man4 Mou5 Sang1 (文武生) – Literally, civilized martial man, this role is known as a clean-shaven scholar-warrior. Actresses for close to a century, of three generations and with huge successes worldwide, usually perform this male role are Yam Kim Fai (mentor and first generation), Loong Kim Sang (protégée and second generation), Koi Ming Fai and Lau Wai Ming (the two youngest listed below both by age and by experience).

- Lou5 Sang1 (老生) – Old man role.

- Sou1 Sang1 (鬚生) – Bearded role

Daan (旦)

These are female roles in Cantonese opera. The different forms of female characters are:

- Faa1 Daan2 (花旦) – Literally 'flower' of the ball, this role is known as a young belle.

- Yi6 Faa1 Daan2 (二花旦) – Literally, second flower, this role is known as a supporting female.

- Mou5 Daan2 (武旦) – Female warrior role.

- Dou1 Maa5 Daan2 (刀馬旦) – Young woman warrior role.

- Gwai1 Mun4 Daan2 (閨門旦) – Virtuous lady role.

- Lou5 Daan2 (老旦) – Old woman role.

Zing (淨)

These characters are known for painted-faces. They are often male characters such as heroes, generals, villains, gods, or demons. Painted-faces are usually:

- Man4 Zing2 (文淨) – Painted-face character that emphasizes on singing.

- Mou5 Zing2 (武淨) – Painted-face character that emphasizes martial arts.

Some characters with painted-faces are:

- Zhang Fei (張飛; Zœng1 Fei1) and Wei Yan (魏延; Ngai6 Jin4) from Three Humiliations of Zhou Yu (三氣周瑜; Saam1 Hei3 Zau1 Jyu4).

- Xiang Yu (項羽; Hong6 Jyu5) from Farewell My Concubine (霸王別姬; Baa3 Wong4 Bit6 Gei1).

- Sun Wukong (孫悟空; Syun1 Ng6 Hung1) and Sha Wujing (沙悟凈; Saa1 Ng6 Zing6) from Journey to the West (西遊記; Sai1 Jau4 Gei3).

Cau (丑)

This is known for clown figures in Cantonese opera. Some examples are:

- Cau2 Sang1 (丑生) – Male clown.

- Cau2 Daan2 (丑旦) – Female clown.

- Man4 Cau2 (文丑) – Clownish civilized male.

- Coi2 Daan2 (彩旦) – Older female clown.

- Mou5 Cau2 (武丑) – Acrobatic comedic role.

Major career artists

Visual elements

Makeup

Applying makeup for Cantonese opera is a long and specialized process. One of the most common styles is the "white and red face": an application of white foundation and a red color around the eyes that fades down to the bottom of cheeks. The eyebrows are black and sometimes elongated. Usually, female characters have thinner eyebrows than males. There is black makeup around the eyes with a shape similar to the eyes of a Chinese phoenix (鳳眼; fung6 ngaan5). Lipstick is usually bright red (口唇膏; hau2 seon4 gou1).

Actors are given temporary facelifts by holding the skin up with a ribbon on the back of the head. This lifts the corners of the eyes, producing an authoritative look.

Each role has its own style of make-up: the clown has a large white spot in the middle of his face, for example. A sick character has a thin red line pointing upwards in between his eyebrows. Aggressive and frustrated character roles often have an arrow shape fading into the forehead in between the eyebrows (英雄脂; jing1 hung4 zi1).

Strong male characters wear "open face" (開面; hoi1 min4) makeup. Each character's makeup has its own distinct characteristics, with symbolic patterns and coloration.

Costumes

Costumes correspond to the theme of the play and indicate the character of each role.

As mentioned above, each type of play is associated with particular costumes. The water sleeves of man (文) plays can be attached to the waist or the sides of the breast areas. Costumes can be single or double breasted.

Costumes also indicate the status of the character. Lower-status characters, such as females, wear less elaborate dresses, while those of higher rank have more decorative costumes.

Major Career Artists (大老倌) listed above, playing the six main characters (generic combination of 2 Sang, 2 Daan, Zing, and Cau), are always supposed to pay for their own costumes.

Overtime, they build a fortune ($millions) by spending most of their income on good quality, such as Sequin (珠片), costumes for each and every performance.

Their collections, measured in number of Chest (furniture) , of such costumes, the quantity, reflect their status as professional performers (大老倌).

Those chests are only sold when they retire or passed for free onto appointed successors. To career artists, Sequin (珠片) costumes are essential for, the main source of income, their commercial, festive performances at various Bamboo Theatres (神功戲)[25] for decades in Hong Kong. These costumes passed from generation to generation of, famous and successful, career performers (大老倌) are priceless, according to some art collectors.

In 1973, Yam Kim Fai gave Loong Kim Sang, her protégée, the complete set of Sequin (珠片) costumes needed for career debut leading her own commercial performance at Chinese New Year Bamboo Theatre.[26][27]

For those not to be used anymore, antiques as well as those of famous artists, Lam Kar Sing[14] and Ng Kwun-Lai,[16] are also on loan or donation to the Hong Kong Heritage Museum regularly.

Hairstyle, hats, and helmets

Hats and helmets signify social status, age and capability: scholars and officials wear black hats with wings on either side; generals wear helmets with pheasants' tail feathers; soldiers wear ordinary hats, and kings wear crowns. Queens or princesses have jeweled helmets. If a hat or helmet is removed, this indicates the character is exhausted, frustrated, or ready to surrender.

Hairstyles can express a character's emotions: warriors express their sadness at losing a battle by swinging their ponytails. For the female roles, buns indicated a maiden, while a married woman has a 'dai tau' (低頭).

In the Three Kingdoms legends, Zhao Yun and especially Lü Bu are very frequently depicted wearing helmets with pheasants' tail feathers; this originates with Cantonese opera, not with the military costumes of their era, although it's a convention that was in place by the Qing Dynasty or earlier.

Aural elements

Speech types

Commentators draw an essential distinction between sung and spoken text, although the boundary is a troublesome one. Speech-types are of a wide variety: one is nearly identical to standard conversational Cantonese, while another is a very smooth and refined delivery of a passage of poetry; some have one form or another of instrumental accompaniment while others have none; and some serve fairly specific functions, while others are more widely adaptable to variety of dramatic needs.

Cantonese opera uses Mandarin or Guān Huà (Cantonese: Gun1 Waa6/2) when actors are involved with government, monarchy, or military. It also obscures words that are taboo or profane from the audience. The actor may choose to speak any dialect of Mandarin, but the ancient Zhōngzhōu (中州; Cantonese: Zung1 Zau1) variant is mainly used in Cantonese opera. Zhōngzhōu is located in the modern-day Hénán (河南) province where it is considered the "cradle of Chinese civilization" and near the Yellow River or Huáng Hé (黃河). Guān Huà retains many of the initial sounds of many modern Mandarin dialects, but uses initials and codas from Middle Chinese. For example, the words 張 and 將 are both pronounced as /tsœːŋ˥˥/ (jyutping: zœng1) in Modern Cantonese, but will respectively be spoken as /tʂɑŋ˥˥/ (pinyin: zhāng) and /tɕiɑŋ˥˥/ (pinyin: jiāng) in operatic Guān Huà. Furthermore, the word 金 is pronounced as /kɐm˥˥/ (jyutping: gam1) in modern Cantonese and /tɕin˥˥/ (pinyin: jīn) in standard Mandarin, but operatic Guān Huà will use /kim˥˥/ (pinyin: gīm). However, actors tend to use Cantonese sounds when speaking Mandarin. For instance, the command for "to leave" is 下去 and is articulated as /saː˨˨ tsʰɵy˧˧/ in operatic Guān Huà compared to /haː˨˨ hɵy˧˧ / (jyutping: haa6 heoi3) in modern Cantonese and /ɕi̯ɑ˥˩ tɕʰy˩/ (pinyin: xià qu) in standard Mandarin.

Music

Cantonese opera pieces are classified either as "theatrical" or "singing stage" (歌壇). The theatrical style of music is further classified into western music (西樂) and Chinese music (中樂). While the "singing stage" style is always Western music, the theatrical style can be Chinese or western music. The "four great male vocals" (四大平喉) were all actresses and notable exponents of the "singing stage" style in the early 20th century.

The western music in Cantonese opera is accompanied by strings, woodwinds, brass plus electrified instruments. Lyrics are written to fit the play's melodies, although one song can contain multiple melodies, performers being able to add their own elements. Whether a song is well performed depends on the performers' own emotional involvement and ability.

Musical instruments

Cantonese instrumental music was called ching yam before the People's Republic was established in 1949. Cantonese instrumental tunes have been used in Cantonese opera, either as incidental instrumental music or as fixed tunes to which new texts were composed, since the 1930s.

The use of instruments in Cantonese opera is influenced by both western and eastern cultures. The reason for this is that Canton was one of the earliest places in China to establish trade relationships with the western civilizations. In addition, Hong Kong was under heavy western influence when it was a British colony. These factors contributed to the observed western elements in Cantonese opera.

For instance, the use of erhu (two string bowed fiddle), saxophones, guitars and the congas have demonstrated how diversified the musical instruments in Cantonese operas are.

The musical instruments are mainly divided into melodic and percussive types.

Traditional musical instruments used in Cantonese opera include wind, strings and percussion. The winds and strings encompass erhu, gaohu, yehu, yangqin, pipa, dizi, and houguan, while the percussion comprises many different drums and cymbals. The percussion controls the overall rhythm and pace of the music, while the gaohu leads the orchestra. A more martial style features the use of the suona.

The instrumental ensemble of Cantonese opera is composed of two sections: the melody section and the percussion section. The percussion section has its own vast body of musical materials, generally called lo gu dim (鑼鼓點) or simply lo gu (鑼鼓). These 'percussion patterns' serve a variety of specific functions.

To see the pictures and listen to the sounds of the instruments, visit page 1 and page 2.

Frequently used terms

- Pheasant feathers (雉雞尾; Cantonese: Ci4 Gai1 Mei5)

- These are attached to the helmet in mou (武) plays, and are used to express the character's skills and expressions. They are worn by both male and female characters.

- Water Sleeves (水袖; Cantonese: Seoi2 Zau6)

- These are long flowing sleeves that can be flicked and waved like water, used to facilitate emotive gestures and expressive effects by both males and females in man (文) plays.

- Hand Movements (手動作; Cantonese: Sau2 Dung6 Zok3)

- Hand and finger movements reflect the music as well as the action of the play. Females hold their hands in the elegant "lotus" form (荷花手; Cantonese: Ho4 Faa1 Sau2).

- Round Table/Walking (圓臺 or 圓台; Cantonese: Jyun4 Toi4)

- A basic feature of Cantonese opera, the walking movement is one of the most difficult to master. Females take very small steps and lift the body to give a detached feel. Male actors take larger steps, which implies travelling great distances. The actors glide across the stage while the upper body is not moving.

- Boots (高靴; Cantonese: Gou1 Hœ1)

- Gwo Wai (過位; Cantonese: Gwo3 Wai6/2)

- This is a movement in which two performers move in a cross-over fashion to opposite sides of the stage.

- Deoi Muk (對目; Cantonese: Deoi3 Muk6)

- In this movement, two performers walk in a circle facing each other and then go back to their original positions.

- "Pulling the Mountains"' (拉山; Cantonese: Laai1 Saan1) and "Cloud Hands" (雲手; Cantonese: Wan4 Sau2)

- These are the basic movements of the hands and arms. This is the MOST important basic movement in ALL Chinese Operas. ALL other movements and skills are based on this form.

- Outward Step (出步; Cantonese: Ceot1 Bou6)

- This is a gliding effect used in walking.

- Small Jump (小跳; Cantonese: Siu2 Tiu3)

- Most common in mou (武) plays, the actor stamps before walking.

- Flying Leg (飛腿; Cantonese: Fei1 Teoi2)

- A crescent kick.

- Hair-flinging (旋水髮; Cantonese: Syun4 Seoi2 Faat3)

- A circular swinging of the ponytail, expressing extreme sadness and frustration.

- Chestbuckle/ Flower (繡花; Cantonese: Sau3 Faa1)

- A flower-shaped decoration worn on the chest. A red flower on the male signifies that he is engaged.

- Horsewhip (馬鞭; Cantonese: Maa5 Bin1)

- Performers swing a whip and walk to imitate riding a horse.

- Sifu (師傅; Cantonese: Si1 Fu6/2)

- Literally, master, this is a formal term, contrary to mentor, for experienced performers and teachers, from whom their own apprentices, other students and young performers learn and follow as disciples.

Reception

Admiration for Cantonese opera has been minimal outside the Chinese community, and even in Hong Kong the popularity has been declining in the past several decades. Most audiences now restricted to the older generation.

Complete collapse was barely averted in 1970s upon the rise of a troupe of young performers led by Loong Kim Sang and her mentor Yam Kim Fai (1913-1989). Record set during the (1975 and 1976) tours in South East Asia still holds today after 40 years. Audience in Singapore surprised all parties writing in English fan mails to these young performers.

In the 1980s, the audiences grew in number and expanded into younger generation. Significant in those ten years was the keen competition between two male leads, Man4 Mou5 Sang1 (文武生).

Lam Kar Sing (1933-2015) and Loong Kim Sang both had a major presence in the decade before Lam Kar Sing retired from stage performance. Such competition has been rare in recent history and could bring back the memory of the 1930s competition (薛馬爭雄) of Sit Gok Sin (1904-1956) and Ma Sze Tsang (1900-1964).[28]

Loong Kim Sang, credited as Lung Kim Sheng, just received encouragement for her effort to remember her mentor Yam Kim Fai and pay-it-forward to bring young, new talents onto stage in 2014. DVD of the event "Ren Yi Sheng Hui Nian Long Qing" (任藝笙輝念濃情), one of the 2015 Best Sales Releases, Classical and Operatic Works Recording, was Live Recording of 2014 stage production. [29]

The DVD has set another historical record for Loong Kim Sang alone to be one of "Ten Best Sales Local Artistes" (Order in Chinese Stroke Counts) again after the award in 2012. In 1979, Sun Ma Sze Tsang (1916-1997) was the first to receive IFPI HKG GOLD DISC AWARD for his album.[30]

These six male leads, the Patriarch of troupe, managed to put on stage commercially successful and critically acclaimed Cantonese opera productions that would also allow their co-stars of all sizes and forms to be Bella of the occasion. Tough acts to follow.

Five of these six pulled themselves up by their own boot straps since none of them were from any dynasty or well-connected. Loong Kim Sang, groomed by mentor Yam Kim Fai for over a decade before commercial performances debut, is also known to have co-stars of equal if not less talents/experience/training (except for the 1972 tour to Vietnam). These SIX all have the ability to teach, lead, guide and train their co-stars as well as bring out the best of the female leads on stage.

For about ten years, 1994 to 2004, all SIX of them were not on stage. The void so left has led to a search for the 'willing and able' to fill those huge shoes. The little boom in early 1990s went out the window and many 'next generation' performers went on to work for TV productions instead.

Boom is back after ten years since the 2005 bust.

The search continues today while Loong Kim Sang returned after a 13-year sabbatical leave in 2005 officially but only sporadically, therefore not sucking all the oxygen out of the room.

For 50 and older, the general consensus is "should have already made it if ever would" or "too late to start that dream". Training takes decades and is best to start before 10 years old.

Very limited resources to search/groom 'willing and able' next few generations of age below 50 (Cantonese Opera Young Talent Showcase – Artists) or even below 45 (Rising Stars 2016/2017) are available from Hong Kong government as well as NGOs while participation of young performers has been growing.

Is the audience still in charge? Do they matter more than powerhouse or dynasty? Hong Kong did it in the past with Loong Kim Sang[31][32] who is now a 55-year veteran top-ranked by both experience and box-office record since beating out competitors on stage instead of backroom deals or connections, family or otherwise.

- over a thousand applicants in 1960,

- fellow 40 plus dancers of 1961,

- over a dozen classmates since 1963,

- fellow performers of same generation.

These young performers are also the audience now and will determine the future of Cantonese opera for a hundred years to come. Their take away from the contemporary business environment is to expect kid's gloves forever or follow the old saying that one should perfect one's craft for the opportunities to come one day.

See also

- Cantopop

- Huangmei Opera

- Beijing Opera

- Music of China

- Music of Hong Kong

- Culture of Hong Kong

- Hong Kong Heritage Museum

- List of Cantonese-related topics

- Chinese Artist Association of Hong Kong

References

- ^ Wordie, Jason (2002). Streets: Exploring Hong Kong Island. Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press. ISBN 962-209-563-1.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ LO, W. (2015). The music culture of older adults in Cantonese operatic singing lessons. Ageing and Society, 35(8), 1614-1634. doi:10.1017/S0144686X14000439

- ^ Wai Han Lo (2016) Traditional opera and young people: Cantonese opera as personal development, International Journal of Adolescence and Youth, 22:2, 238-249, DOI: 10.1080/02673843.2016.1163503

- ^ 王勝泉, 張文珊(2011)編,香港當代粵劇人名錄,中大音樂系 The Chinese University Press (Description and Author Information) ISBN 978-988-19881-1-9

- ^ His wife Yu So-chow

- ^ Artistic Director:Yuen Siu-fai

- ^ 2010 Hong Kong Arts Development Awards 2010 Presentation Ceremony

- ^ Artistic Director:Wan Fai-yin

- ^ [1]

- ^ [2]

- ^ Rehearsal of "Red Silk Shoes and The Murder" (16.1.2016)

- ^ Artistic Director:Law Ka-ying

- ^ Rehearsal of "Merciless Sword Under Merciful Heaven" (19.1.2016)

- ^ a b "Lam Kar Sing". Virtuosity and Innovation – The Masterful Legacy of Lam Kar Sing 20 July 2011 – 14 May 2012.

- ^ a b c d e Iconic Heroines in Cantonese Opera Films

- ^ a b "Ng Kwun-Lai". A Synthesis of Lyrical Excellence and Martial Agility – The Stage Art of Ng Kwan Lai 22 December 2004 – 15 September 2005.

- ^ a b c d Famed female Cantonese opera singers Xiao Minxin, Xu Liu-xian, Zhang Yue'r and Zhang Hui-fang 6 December 2011 Hong Kong Central Library

- ^ Xiao Mingxing zhuan (1952) at IMDb

- ^ Yam Kim Fai 有"女桂名揚"之稱的任劍輝 is one of the more famous exponent of Kwai Ming Yeung style of acting and vocal (腔). Movie The Red Robe(1965) demonstrates ‘masculine’ traits of Yam style(任腔).

- ^ Kwai Ming Yeung style 聽"桂派"名曲 藝海 2010-07-08

- ^ Story of Mei in the North and Suet in the South 戲曲視窗:「北梅南雪」的故事 – 香港文匯報 2016-01-26

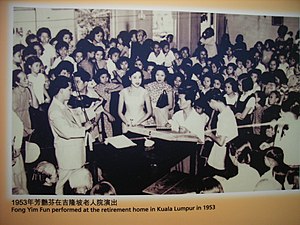

- ^ Heritage Museum Exhibition to feature the female Cantonese opera artist Fong Yim Fun as of 8 October 2002

- ^ The queen who came back to her people by Fionnuala McHugh SCMP Updated : Thursday, 16 July, 1998, 12:00am

- ^ CANTONESE OPERA YOUNG TALENT SHOWCASE – Artists Only about 15 in male costumes are lead actors. Actresses dominate as a result of the Yam-Loong Effect for over five decades. Both Koi Ming Fai and Lau Wai Ming were not old enough to be in the audience for Yam's final performance on stage in 1969.

- ^ 2010 to 2015 Time table of Chinese Artist Association of Hong Kong 香港八和會館 神功戲台期表

- ^ Maybe The Cantonese Opera Diva Archived February 24, 2016, at the Wayback Machine January 01, 2016 Australia

- ^ 舞台下的龍劍笙 November 14, 2015 Hong Kong

- ^ Radio broadcast May 25, June 01, June 08 and June 15, 1985, 紅伶訴心聲: 靚次伯, Lang Chi Bak, the classmate of Sit Gok Sin and co-worker of all four male leads at one point of their career, Hong Kong

- ^ 任藝笙輝念濃情 IFPI HKG 2015 List of Best Sales Releases, Classical and Operatic Works Recording (Order in Chinese Stroke Counts)

- ^ 萬惡淫為首 1979 IFPI HKG GOLD DISC AWARD

- ^ How Hong Kong box-office driven environment worked so much better than otherwise. 評戲曲發展:香港粵劇興盛的啟示 2013年03月14日

- ^ Growing Pain. 戲曲視窗:粵劇新人成長困難 – 香港文匯報 2011-06-07

External links

- Bay Area Cantonese Opera

- More Cantonese Opera Artists

- Can You Hear Me?: The Female Voice and Cantonese Opera in the San Francisco Bay Area The Scholar and Feminist Online