Enver Hoxha

Enver Hoxha | |

|---|---|

| |

| First Secretary of the Party of Labour of Albania | |

| In office 8 November 1941 – 11 April 1985 | |

| Preceded by | Position created |

| Succeeded by | Ramiz Alia |

| 2nd Chairman of the Council of Ministers of the People's Republic of Albania | |

| In office 24 October 1944 – 18 July 1954 | |

| Preceded by | Ibrahim Biçakçiu (as Prime Minister of Albania) |

| Succeeded by | Mehmet Shehu |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 16 October 1908 Ergiri (Gjirokastër), Janina Vilayet, Ottoman Empire |

| Died | 11 April 1985 (aged 76) Tirana, Albania |

| Nationality | Albanian |

| Political party | Labour of Albania |

| Spouse | Nexhmije Hoxha |

| Children | Ilir Sokol Pranvera |

Enver Halil Hoxha (Albanian pronunciation: [ɛnˈvɛɾ ˈhɔdʒa] ; 16 October 1908 – 11 April 1985)[1] was the communist leader of Albania from 1944 until his death in 1985, as the First Secretary of the Party of Labour of Albania. He was chairman of the Democratic Front of Albania and commander-in-chief of the armed forces from 1944 until his death. He served as Prime Minister of Albania from 1944 to 1954 and at various times served as foreign minister and defence minister as well.

The 40-year period of Hoxha's rule was characterized by the elimination of the opposition, prolific use of the death penalty[2][3] or long prison terms for his political opponents and evictions of their families from their homes to remote villages that were strictly controlled by police and the secret police (Sigurimi). His rule was also characterized by the use of Stalinist methods to destroy associates who threatened his power.[4] He focused on rebuilding the country, which was left in ruins after World War II, building Albania's first railway line, eliminating adult illiteracy and leading Albania towards becoming agriculturally self-sufficient.[5]

Hoxha's government was characterized by his proclaimed firm adherence to anti-revisionist Marxism–Leninism from the mid-1970s onwards. After his break with Maoism in the 1976–78 period, numerous Maoist parties declared themselves Hoxhaist. The International Conference of Marxist–Leninist Parties and Organizations (Unity & Struggle) is the best known association of these parties today.

Early life

Hoxha was born in Gjirokastër, a city in southern Albania (then under the Ottoman Empire) that has been home to many prominent families. He was the son of Halil Hoxha, a Muslim: "[Enver Hoxha was] from the Gjirokastër area and [he] came from [a family] that [was] attached to the Bektashi tradition. In fact, fourteen years before Enver set off for France to study, his father brought him to seek the blessing of Baba Selim. The baba (dervish) was not one to refuse the request of a petitioner and he made a benediction over the boy." Tosk cloth merchant who travelled widely across Europe and the United States, and Gjylihan (Gjylo) Hoxha. Fourteen years before Enver set off for France to study, his father brought him to seek the blessing of Baba Selim of the Zall Teqe. The baba did not refuse the request of the petitioner and made a benediction over the boy.[6]

At age 16, Hoxha helped found and became secretary of the Students Society of Gjirokastër, which protested against the monarchist government of Zog I. After the government closed the Society, he moved to Korçë, continuing his studies in a French secondary school. There he learned French history, literature and philosophy, and read the Communist Manifesto for the first time.[7]

In 1930, Hoxha went to study at the University of Montpellier in France on a state scholarship given to him by the Queen Mother for the faculty of natural sciences. He attended the lessons and the conferences of the Association of Workers organised by the French Communist Party, but dropped out to pursue a degree in either philosophy or law. After a year, lacking interest in biology, and after not having passed any university exams, he left Montpellier to go to Paris hoping to continue his studies. He attended philosophy classes at Sorbonne, but, again, did not sit for any exam. In Paris, it is said that he collaborated with L'Humanité, writing articles on the situation in Albania under the pseudonym Lulo Malësori. He also got involved in the Albanian Communist Group under the tutelage of Llazar Fundo, who taught him law.[8]

He dropped out once more, and from 1934 to 1936 he was a secretary at the Albanian consulate in Brussels, attached to the personnel office of the Queen Mother. He was dismissed after the consul discovered that his employee kept Marxist materials and books in his office. He returned to Albania in 1936 and taught grammar school in the French Lyceum of Korçë. His extensive education left him fluent in French with a working knowledge of Italian, Croatian, English and Russian. As a leader, he would often reference Le Monde and the International Herald Tribune.[9]

On 7 April 1939, Albania was invaded by Fascist Italy.[10] The Italians established a puppet government in Albania under Mustafa Merlika-Kruja.[11] Hoxha was dismissed from his teaching post following the invasion for refusing to join the Albanian Fascist Party.[12] He opened a tobacco shop in Tirana called Flora where a small communist group soon started gathering. Eventually the government closed it.[13]

Partisan life

On 8 November 1941, the Communist Party of Albania (later renamed the Albanian Party of Labour in 1948) was founded. Hoxha was chosen from the "Korca group" as a Muslim representative by the two Yugoslav envoys as one of the seven members of the provisional Central Committee. From 8 to 11 April 1942, the First Consultative Meeting of Activists of the Communist Party of Albania was held in Tirana.[14] Enver Hoxha delivered the main report on 8 April 1942.[15]

In July 1942, Hoxha wrote "Call to the Albanian Peasantry," issued in the name of the Communist Party of Albania.[16] The call sought to enlist support in Albania for the war against the fascists. The peasants were encouraged to hoard their grain and refuse to pay taxes or livestock levies brought by the government.[17] After the September 1942 Conference at Pezë, the National Liberation Front was founded with the purpose of uniting the anti-Fascist Albanians, regardless of ideology or class.

By March 1943, the first National Conference of the Communist Party elected Hoxha formally as First Secretary. During World War II, the Soviet Union's role was negligible.[18] On 10 July 1943, the Albanian partisan groups were organised in regular units of companies, battalions and brigades and named the Albanian National Liberation Army. The organization received military support from the British intelligence service, SOE.[19] The General Headquarters was created with Spiro Moisiu as the commander and Hoxha as political commissar. Communist partisans in Yugoslavia had a much more practical role, helping to plan attacks and exchanging supplies, but communication between them and the Albanians was limited and letters would often arrive late, sometimes well after a plan had been agreed upon by the National Liberation Army without consultation from the Yugoslav partisans.

Within Albania, repeated attempts were made during the war to remedy the communications difficulties which faced partisan groups. In August 1943, a secret meeting was held in Mukje between the anti-communist Balli Kombëtar (National Front) and the Communist Party of Albania. The result of this was an agreement to:

- Unite in a single struggle against the fascist invader.

- Cease all attacks between the two parties signing the agreement.

- Form a joint operational staff to coordinate military actions within Albania.

- Recognize that the democratically elected national liberations councils are the state power in Albania.

- Recognize that the goal for the post-war era is an independent, democratic Albania where the people themselves will decide the form of government.

- Recognize and respect the Atlantic Charter, the London and Washington Treaties between the USSR, Great Britain and the United States in connection with the question of Kosovo and Çamëria. Be it resolved that the populations of Kosovo and Camëria will themselves decide their future in accordance with their wishes.

- Unite with any political group, whatever their beliefs, in a common military effort against the fascist invaders.

- However, the Communist Party of Albania will not collaborate with any group of the National Front that continues to maintain contacts with the fascist invaders.

- The Communist Party of Albania will unite with any group that used to have contacts with the fascist invaders, but has now terminated those contacts and is willing to now fight against the fascist invaders, provided those groups have not committed any crimes against the people.[20]

To encourage the Balli Kombëtar to sign, the Greater Albania sections that included Kosovo (part of Yugoslavia) and Çamëria (part of Greece) were made part of the Agreement.[21]

Disagreement with Yugoslav communists

A problem developed when the Yugoslav Communists disagreed with the goal of a Greater Albania and asked the Communists in Albania to withdraw their agreement. According to Hoxha, Josip Broz Tito had agreed that "Kosovo was Albanian" but that Serbian opposition made transfer an unwise option.[22] After the Albanian Communists repudiated the Greater Albania agreement, the Balli Kombëtar condemned the Communists, who in turn accused the Balli Kombëtar of siding with the Italians. The Balli Kombëtar, however, lacked support from the people. After judging the Communists as an immediate threat, the Balli Kombëtar sided with the Germans, fatally damaging its image among those fighting the Fascists. The Communists quickly added to their ranks many of those disillusioned with the Balli Kombëtar and took center stage in the fight for liberation.[23]

The Permet National Congress held during that time called for a "new democratic Albania for the people." Although the monarchy was not formally abolished, King Zog was barred from returning to the country, which further increased the Communists' control. The Anti-Fascist Committee for National Liberation was founded, chaired by Hoxha. On 22 October 1944, the Committee became the Democratic Government of Albania after a meeting in Berat and Hoxha was chosen as interim Prime Minister. Tribunals were set up to try alleged war criminals who were designated "enemies of the people"[24] and were presided over by Koçi Xoxe.

After liberation on 29 November 1944, several Albanian partisan divisions crossed the border into German-occupied Yugoslavia, where they fought alongside Tito's partisans and the Soviet Red Army in a joint campaign which succeeded in driving out the last pockets of German resistance. Marshal Tito, during a Yugoslavian conference in later years, thanked Hoxha for the assistance that the Albanian partisans had given during the War for National Liberation (Lufta Nacionalçlirimtare). The Democratic Front, dominated by the Albanian Communist Party, succeeded the National Liberation Front in August 1945 and the first elections in post-war Albania were held on 2 December. The Front was the only legal political organisation allowed to stand in the elections, and the government reported that 93% of Albanians voted for it.[25]

On 11 January 1946, Zog was officially deposed and Albania was proclaimed the People's Republic of Albania (renamed the People's Socialist Republic of Albania in 1976). As First Secretary, Hoxha was de facto head of state and the most powerful man in the country.[26]

Albanians celebrate their independence day on 28 November (which is the date on which they declared their independence from the Ottoman Empire in 1912), while in the former People's Socialist Republic of Albania the national day was 29 November, the day the country was liberated from the Italians. Both days are currently national holidays.

Early leadership (1946–65)

The sacrifices of our people were very great. Out of a population of one million, 28,000 were killed, 12,600 wounded, 10,000 were made political prisoners in Italy and Germany, and 35,000 made to do forced labour, of ground; all the communications, all the ports, mines and electric power installations were destroyed, our agriculture and livestock were plundered, and our entire national economy was wrecked.

— Enver Hoxha[27]

Hoxha declared himself a Marxist–Leninist and strongly admired Soviet leader Joseph Stalin. During the period of 1945–1950, the government adopted policies which were intended to consolidate power. The Agrarian Reform Law was passed in August 1945. It confiscated land from beys and large landowners, giving it without compensation to peasants. 52% of all land was owned by large landowners before the law was passed; this declined to 16% after the law's passage.[28] Illiteracy, which was 90–95% in rural areas in 1939 went down to 30% by 1950 and by 1985 it was equal to that of a Western country.[29]

The State University of Tirana was established in 1957, which was the first of its kind in Albania. The Medieval Gjakmarrja (blood feud) was banned. Malaria, the most widespread disease,[30] was successfully fought through advances in health care, the use of DDT, and through the draining of swamplands. From 1965 to 1985, no cases of malaria were reported, whereas previously Albania had the greatest number of infected patients in Europe.[31] No cases of syphilis had been recorded for 30 years.[31] In order to solve the Gheg-Tosk divide, books were written in the Tosk dialect, and the majority of the Party's members came from southern Albania where the Tosk dialect is spoken.

By 1949, the United States and British intelligence organisations were working with King Zog and the mountain men of his personal guard. They recruited Albanian refugees and émigrés from Egypt, Italy and Greece, trained them in Cyprus, Malta and the Federal Republic of Germany (West Germany), and infiltrated them into Albania. Guerrilla units entered Albania in 1950 and 1952, but they were killed or captured by Albanian security forces. Kim Philby, a Soviet double agent working as a liaison officer between the British intelligence service and the United States Central Intelligence Agency, had leaked details of the infiltration plan to Moscow, and the security breach claimed the lives of about 300 infiltrators.[32]

Relations with Yugoslavia

At this point, relations with Yugoslavia had begun to change. The roots of the change began on 20 October 1944 at the Second Plenary Session of the Communist Party of Albania. The Session considered the problems that the post-independence Albanian government would face. However, the Yugoslav delegation led by Velimir Stoinić accused the party of "sectarianism and opportunism" and blamed Hoxha for these errors. He also stressed the view that the Yugoslav Communist partisans spearheaded the Albanian partisan movement.[33]

Anti-Yugoslav members of the Albanian Communist Party had begun to think that this was a plot by Tito who intended to destabilize the Party. Koçi Xoxe, Sejfulla Malëshova and others who supported Yugoslavia were looked upon with deep suspicion. Tito's position on Albania was that it was too weak to stand on its own and that it would do better as a part of Yugoslavia. Hoxha alleged that Tito had made it his goal to get Albania into Yugoslavia, firstly by creating the Treaty of Friendship, Co-operation and Mutual Aid in 1946. In time, Albania began to feel that the treaty was heavily slanted towards Yugoslav interests, much like the Italian agreements with Albania under Zog that made the nation dependent upon Italy.[33]

The first issue was that the Albanian lek became revalued in terms of the Yugoslav dinar as a customs union was formed and Albania's economic plan was decided more by Yugoslavia.[34] Albanian economists H. Banja and V. Toçi stated that the relationship between Albania and Yugoslavia during this period was exploitative and that it constituted attempts by Yugoslavia to make the Albanian economy an "appendage" to the Yugoslav economy.[35] Hoxha then began to accuse Yugoslavia of misconduct:

We [Albania] were expected to produce for the Yugoslavs all the raw materials which they needed. These raw materials were to be exported to the metropolitan Yugoslavia to be processed there in Yugoslav factories. The same applied to the production of cotton and other industrial crops, as well as oil, bitumen, asphalt, chrome, etc. Yugoslavia would supply its 'colony', Albania, with exorbitantly priced consumer goods, including even items such as needles and thread, and would provide us with petrol and oil, as well as glass for the lamps in which we burn the fuel extracted from our subsoil, processed in Yugoslavia and sold to us at high prices ... The aim of the Yugoslavs was, therefore, to prevent our country from developing either its industry or its working class, and to make it forever dependent on Yugoslavia.[36]

Joseph Stalin advised Hoxha that Yugoslavia was attempting to annex Albania: "We did not know that the Yugoslavs, under the pretext of 'defending' your country against an attack from the Greek fascists, wanted to bring units of their army into the PRA [People's Republic of Albania]. They tried to do this in a very secretive manner. In reality, their aim in this direction was utterly hostile, for they intended to overturn the situation in Albania."[37] By June 1947, the Central Committee of Yugoslavia began publicly condemning Hoxha, accusing him of talking an individualistic and anti-Marxist line. When Albania responded by making agreements with the Soviet Union to purchase a supply of agricultural machinery, Yugoslavia said that Albania could not enter into any agreements with other countries without Yugoslav approval.[38]

Koçi Xoxe tried to stop Hoxha from improving relations with Bulgaria, reasoning that Albania would be more stable with one trading partner rather than with many. Nako Spiru, an anti-Yugoslav member of the Party, condemned Xoxe and vice versa. With no one coming to Spiru's defense, he viewed the situation as hopeless and feared that Yugoslav domination of his nation was imminent, which caused him to commit suicide in November.[38]

At the Eighth Plenum of the Central Committee of the Party which lasted from 26 February to 8 March 1948, Xoxe was implicated in a plot to isolate Hoxha and consolidate his own power. He accused Hoxha of being responsible for the decline in relations with Yugoslavia, and stated that a Soviet military mission should be expelled in favor of a Yugoslav counterpart. Hoxha managed to remain firm and his support had not declined. When Yugoslavia publicly broke with the Soviet Union, Hoxha's support base grew stronger. Then, on 1 July 1948, Tirana called on all Yugoslav technical advisors to leave the country and unilaterally declared all treaties and agreements between the two countries null and void. Xoxe was expelled from the party and on 13 June 1949 he was executed by a firing squad.[39]

Relations with the Soviet Union

After the break with Yugoslavia, Hoxha aligned himself with the Soviet Union, for which he had a great admiration. From 1948 to 1960, $200 million in Soviet aid was given to Albania for technical and infrastructural expansion. Albania was admitted to the Comecon on 22 February 1949 and remained important both as a way to pressure Yugoslavia and to serve as a pro-Soviet force in the Adriatic Sea. A submarine base was built on the island of Sazan near Vlorë, posing a possible threat to the United States Sixth Fleet. Relations remained close until the death of Stalin on 5 March 1953. His death was met with 14 days of national mourning in Albania—more than in the Soviet Union.[40] Hoxha assembled the entire population in the capital's largest square featuring a statue of Stalin, requested that they kneel, and made them take a two-thousand word oath of "eternal fidelity" and "gratitude" to their "beloved father" and "great liberator" to whom the people owed "everything."[41]

Under Nikita Khrushchev, Stalin's successor, aid was reduced and Albania was encouraged to adopt Khrushchev's specialization policy. Under this policy, Albania would develop its agricultural output in order to supply the Soviet Union and other Warsaw Pact nations while these nations would be developing specific resource outputs of their own, which would in theory strengthen the Warsaw Pact by greatly reducing the lack of certain resources that many of the nations faced. However, this also meant that Albanian industrial development, which was stressed heavily by Hoxha, would have to be significantly reduced.[42]

From 16 May to 17 June 1955, Nikolai Bulganin and Anastas Mikoyan visited Yugoslavia and Khrushchev renounced the expulsion of Yugoslavia from the Communist bloc. Khrushchev also began making references to Palmiro Togliatti's polycentrism theory. Hoxha had not been consulted on this and was offended. Yugoslavia began asking for Hoxha to rehabilitate the image of Koçi Xoxe, which Hoxha steadfastly rejected. In 1956 at the Twentieth Party Congress of the Soviet Communist Party, Khrushchev condemned the cult of personality that had been built up around Joseph Stalin and also accused him of many grave mistakes. Khrushchev then announced the theory of peaceful coexistence, which angered Hoxha greatly. The Institute of Marxist–Leninist Studies, led by Hoxha's wife Nexhmije, quoted Vladimir Lenin: "The fundamental principle of the foreign policy of a socialist country and of a Communist party is proletarian internationalism; not peaceful coexistence."[43] Hoxha now took a more active stand against perceived revisionism.

Unity within the Albanian Party of Labour began to decline as well, with a special delegate meeting held in Tirana in April 1956, composed of 450 delegates and having unexpected results. The delegates "criticized the conditions in the party, the negative attitude toward the masses, the absence of party and socialist democracy, the economic policy of the leadership, etc." while also calling for discussions on the cult of personality and the Twentieth Party Congress.[44]

Movement towards China and Maoism

In 1956, Hoxha called for a resolution which would uphold the current leadership of the Party. The resolution was accepted, and all of the delegates who had spoken out were expelled from the party and imprisoned. Hoxha stated that this was yet another of many attempts to overthrow the leadership of Albania which had been organized by Yugoslavia. This incident further consolidated Hoxha's power, effectively making Khrushchev-esque reforms nearly impossible. In the same year, Hoxha traveled to the People's Republic of China, then enduring the Sino-Soviet Split, and personally met with Mao Zedong. Relations with China improved, as evidenced by Chinese aid to Albania being 4.2% in 1955 before the visit, and rising to 21.6% in 1957.[45]

In an effort to keep Albania in the Soviet sphere, increased aid was given but the Albanian leadership continued to move closer towards China. Relations with the Soviet Union remained at the same level until 1960, when Khrushchev met with Sophocles Venizelos, a left-wing Greek politician. Khrushchev sympathized with the concept of an autonomous Greek North Epirus and hoped to use Greek claims to keep the Albanian leadership in line with Soviet interests.[46] Hoxha reacted by only sending Hysni Kapo, a member of the Albanian Political Bureau, to the Third Congress of the Romanian Communist Party in Bucharest, an event that heads of state were normally expected to attend.[47] As relations between the two countries continued to deteriorate in the course of the meeting, Khrushchev said:

Especially shameless was the behavior of that agent of Mao Zedong, Enver Hoxha. He bared his fangs at us even more menacingly than the Chinese themselves. After his speech, Comrade Dolores Ibárruri [a Spanish Communist], an old revolutionary and a devoted worker in the Communist movement, got up indignantly and said, very much to the point, that Hoxha was like a dog who bites the hand that feeds it.[48]

Friction with the Soviet Union

Relations with the Soviet Union began to decline rapidly. A hardline policy was adopted and the Soviets reduced aid shipments, specifically grain, at a time when Albania needed them due to the possibility of a flood-induced famine.[49] In July 1960, a plot to overthrow the government was discovered. It was to be organized by Soviet-trained Rear Admiral Teme Sejko. After this, two pro-Soviet members of the Party, Liri Belishova and Koço Tashko, were expelled, with a humorous incident involving Tashko pronouncing tochka (Russian for "full stop").[50]

In August, the Party's Central Committee sent a letter of protest to the Central Committee of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union, stating its displeasure at having an anti-Albanian Soviet Ambassador in Tirana. The Fourth Congress of the Party, held from 13 to 20 February 1961, was the last meeting that the Soviet Union or other Eastern European nations attended in Albania. During the congress, the Soviet Union was condemned while China was praised. Mehmet Shehu stated that while many members of the Party were accused of tyranny, this was a baseless charge and unlike the Soviet Union, Albania was led by genuine Marxists.

The Soviet Union retaliated by threatening "dire consequences" if the condemnations were not retracted. Days later, Khrushchev and Antonín Novotný, President of Czechoslovakia (which was Albania's largest source of aid besides the Soviets), threatened to cut off economic aid. In March, Albania was not invited to attend the meeting of the Warsaw Pact nations (Albania had been one of its founding members in 1955) and in April all Soviet technicians were withdrawn from the nation. In May nearly all Soviet troops on the Orikum naval base were withdrawn, leaving the Albanians with 4 submarines and other military equipment.

On 7 November 1961, Hoxha made a speech in which he called Khrushchev a "revisionist, an anti-Marxist and a defeatist." Hoxha portrayed Stalin as the last Communist leader of the Soviet Union and began to stress Albania's independence.[51] By 11 November, the USSR and every other Warsaw Pact nation broke relations with Albania. Albania was unofficially excluded (by not being invited) from both the Warsaw Pact and Comecon. The Soviet Union also attempted to claim control of the Vlorë port due to a lease agreement; the Albanian Party then passed a law prohibiting any other nation from owning an Albanian port through lease or otherwise.

Later rule

As Hoxha's leadership continued he took on an increasingly theoretical stance. He wrote criticisms based both on current events at the time and on theory; most notably his condemnations of Maoism post-1978.[52] A major achievement under Hoxha was the advancement of women's rights. Albania had been one of the most, if not the most, patriarchal countries in Europe. The Code of Lekë, which regulated the status of women, states, "A woman is known as a sack, made to endure as long as she lives in her husband's house."[53] Women were not allowed to inherit anything from their parents, and discrimination was even made in the case of the murder of a pregnant woman:

... the dead woman [is] to be opened up, in order to see whether the fetus is a boy or a girl. If it is a boy, the murderer must pay 3 purses [a set amount of local currency] for the woman's blood and 6 purses for the boy's blood; if it is a girl, aside from the three purses for the murdered woman, 3 purses must also be paid for the female child.[54]

Women were forbidden to obtain a divorce, and the wife's parents were obliged to return a runaway daughter to the husband or else suffer shame which could even result in a generations-long blood feud. During World War II, the Albanian Communists encouraged women to join the partisans,[55] and following the war women were encouraged to take up menial jobs, as the education necessary for higher level work was out of most women's reach. In 1938, 4% worked in various sectors of the economy. In 1970, this number rose to 38%, and in 1982 to 46%.[56]

During the Cultural and Ideological Revolution (discussed below), women were encouraged to take up all jobs, including government posts, which resulted in 40.7% of the People's Councils and 30.4% of the People's Assembly being made up of women, including two women in the Central Committee by 1985.[57] In 1978, 15.1 times as many females attended eight-year schools as had done so in 1938 and 175.7 times as many females attended secondary schools. By 1978, 101.9 times as many women attended higher schools as in 1957.[58] Hoxha said of women's rights in 1967:

The entire party and country should hurl into the fire and break the neck of anyone who dared trample underfoot the sacred edict of the party on the defense of women's rights.[59]

In 1969, direct taxation was abolished[60] and during this period the quality of schooling and health care continued to improve. An electrification campaign was begun in 1960 and the entire nation was expected to have electricity by 1985. Instead, it achieved this on 25 October 1970, making it the first nation with complete electrification in the world.[61][better source needed] During the Cultural & Ideological Revolution of 1967–1968 the military changed from traditional Communist army tactics and began to adhere to the Maoist strategy known as people's war, which included the abolition of military ranks, which were not fully restored until 1991.[62] Mehmet Shehu said of the country's health service in 1979:

... [T]he health service is free of charge for all and has been extended to the remotest villages. In 1960 we had one doctor per every 3,360 inhabitants, in 1978 we had one doctor per every 687 inhabitants, and this despite the rapid growth of the population. The natural increase of the population in our country is 3.5 times higher than the annual average of European countries, whereas mortality in 1978 was 37% lower than the average level of mortality in the countries of Europe, and the average life expectancy in our country has risen, from about 38 years in 1938 to 69 years. That is, for each year of the existence of our people's state power, the average life expectancy has risen by about 11 months. That is what socialism does for man! Is there a loftier humanism than socialist humanism, which, in 35 years, doubles the average life expectancy of the whole population of the country?[63]

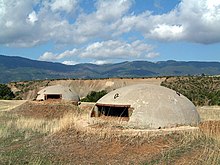

Hoxha's legacy also included a complex of 750,000 one-man concrete bunkers across a country of 3 million inhabitants, to act as look-outs and gun emplacements along with chemical weapons.[64] The bunkers were built strong and mobile, with the intention that they could be easily placed by a crane or a helicopter in a previously dug hole. The types of bunkers vary from machine gun pillboxes, beach bunkers, to underground naval facilities, and even Air Force Mountain and underground bunkers.

Hoxha's internal policies were true to Stalin's paradigm which he admired, and the personality cult developed in the 1970s organized around him by the Party also bore a striking resemblance to that of Stalin. At times it even reached an intensity similar to the personality cult surrounding Kim Il Sung (which Hoxha condemned[65]) with Hoxha being portrayed as a genius commenting on virtually all facets of life from culture to economics to military matters. Each schoolbook required one or more quotations from him on the subjects being studied.[66] The Party honored him with titles such as Supreme Comrade, Sole Force and Great Teacher.

Hoxha's governance was also distinguished by his encouragement of a high birthrate policy. For instance, a woman who bore an above-average amount of children would be given the government award of Heroine Mother (in Albanian: Nënë Heroinë) along with cash rewards.[67] Abortion was essentially restricted (to encourage high birth rates), except if the birth posed a danger to the mother's life, though it was not completely banned; the process being decided by district medical commissions.[68][69] As a result, the population of Albania tripled from 1 million in 1944 to around 3 million in 1985.

Relations with China

In Albania's Third Five Year Plan, China promised a loan of $125 million to build twenty-five chemical, electrical and metallurgical plants called for under the Plan. However, the nation had a difficult transition period, because Chinese technicians were of a lower quality than Soviet ones and the distance between the two nations, plus the poor relations Albania had with its neighbors, further complicated matters. Unlike Yugoslavia or the USSR, China had less influence economically on Albania during Hoxha's leadership. The previous fifteen years (1946–1961) had at least 50% of the economy under foreign commerce.[71]

By the time the 1976 Constitution prohibited foreign debt, aid and investments, Albania had basically become self-sufficient although it was lacking in modern technology. Ideologically, Hoxha found Mao's initial views to be in line with Marxism-Leninism. Mao condemned Nikita Khrushchev's alleged revisionism and was also critical of Yugoslavia. Aid given from China was interest-free and did not have to be repaid until Albania could afford to do so.[72]

China never intervened in what Albania's economic output should be, and Chinese technicians worked for the same wages as Albanian workers, unlike Soviet technicians who sometimes made more than three times the pay of Hoxha.[72] Albanian newspapers were reprinted in Chinese newspapers and read on Chinese radio. Finally, Albania led the movement to give the People's Republic of China a seat in the UN, an effort made successful in 1971 and thus replacing the Republic of China's seat.[73]

During this period, Albania became the second largest producer of chromium in the world, which was considered an important export for Albania. Strategically, the Adriatic Sea was also attractive to China, and the Chinese leadership had hoped to gain more allies in Eastern Europe with the help of Albania, although this failed. Zhou Enlai visited Albania in January 1964. On 9 January, "The 1964 Sino-Albanian Joint Statement" was signed in Tirana.[74] The statement said of relations between socialist countries:

Both [Albania and China] hold that the relations between socialist countries are international relations of a new type. Relations between socialist countries, big or small, economically more developed or less developed, must be based on the principles of complete equality, respect for territorial sovereignty and independence, and non-interference in each other's internal affairs, and must also be based on the principles of mutual assistance in accordance with proletarian internationalism. It is necessary to oppose great-nation chauvinism and national egoism in relations between socialist countries. It is absolutely impermissible to impose the will of one country upon another, or to impair the independence, sovereignty and interests of the people, of a fraternal country on the pretext of 'aid' or 'international division of labour.'[75]

Like Albania, China defended the "purity" of Marxism by attacking both US imperialism as well as "Soviet and Yugoslav revisionism", both equally as part of a "dual adversary" theory.[76] Yugoslavia was viewed as a "special detachment of U.S. imperialism" and a "saboteur against world revolution."[76] These views however began to change in China, which was one of the major issues Albania had with the alliance.[77] Also unlike Yugoslavia and the Soviet Union, the Sino-Albanian alliance lacked "... an organizational structure for regular consultations and policy coordination, and was characterized by an informal relationship conducted on an ad hoc basis." Mao made a speech on 3 November 1966 which claimed that Albania was the only Marxist-Leninist state in Europe and that "an attack on Albania will have to reckon with great People's China. If the U.S. imperialists, the modern Soviet revisionists or any of their lackeys dare to touch Albania in the slightest, nothing lies ahead for them but a complete, shameful and memorable defeat."[78] Likewise, Hoxha stated that "You may rest assured, comrades, that come what may in the world at large, our two parties and our two peoples will certainly remain together. They will fight together and they will win together."[79]

Shift in Chinese foreign policy after the Cultural Revolution

China entered into a four-year period of relative diplomatic isolation following the Cultural Revolution and at this point relations between China and Albania reached their zenith. On 20 August 1968, the Soviet invasion of Czechoslovakia was condemned by Albania, as was the Brezhnev doctrine. Albania then officially withdrew from the Warsaw Pact on 5 September. Relations with China began to deteriorate on 15 July 1971, when United States President Richard Nixon agreed to visit China to meet with Zhou Enlai. Hoxha felt betrayed and the government was in a state of shock. On 6 August a letter was sent from the Central Committee of the Albanian Party of Labour to the Central Committee of the Communist Party of China, calling Nixon a "frenzied anti-Communist." The letter stated:

We trust you will understand the reason for the delay in our reply. This was because your decision came as a surprise to us and was taken without any preliminary consultation between us on this question, so that we would be able to express and thrash out our opinions. This, we think, could have been useful, because preliminary consultations, between close friends, determined co-fighters against imperialism and revisionism, are useful and necessary, and especially so, when steps which, in our opinion, have a major international effect and repercussion are taken. ...Considering the Communist Party of China as a sister party and our closest co-fighter, we have never hidden our views from it. That is why on this major problem which you put before us, we inform you that we consider your decision to receive Nixon in Beijing as incorrect and undesirable, and we do not approve or support it. It will also be our opinion that Nixon's announced visit to China will not be understood or approved of by the peoples, the revolutionaries and the communists of different countries.[80]

The result was a 1971 message from the Chinese leadership stating that Albania could not depend on an indefinite flow of further Chinese aid and in 1972 Albania was advised to "curb its expectations about further Chinese contributions to its economic development."[81] By 1973, Hoxha wrote in his diary Reflections on China that the Chinese leaders:

... have cut off their contacts with us, and the contacts which they maintain are merely formal diplomatic ones. Albania is no longer the 'faithful, special friend'... They are maintaining the economic agreements though with delays, but it is quite obvious that their 'initial ardor' has died.[82]

In response, trade with COMECON (although trade with the Soviet Union was still blocked) and Yugoslavia grew. Trade with Third World nations was $0.5 million in 1973, but $8.3 million in 1974. Trade rose from 0.1% to 1.6%.[83] Following Mao's death on 9 September 1976, Hoxha (who attended Mao's funeral in Beijing) remained optimistic about Sino-Albanian relations, but in August 1977, Hua Guofeng, the new leader of China, stated that Mao's Three Worlds Theory would become official foreign policy. Hoxha viewed this as a way for China to justify having the U.S. as the "secondary enemy" while viewing the Soviet Union as the main one, thus allowing China to trade with the U.S. "... the Chinese plan of the 'third world' is a major diabolical plan, with the aim that China should become another superpower, precisely by placing itself at the head of the 'third world' and 'non-aligned world.'"[84] From 30 August to 7 September 1977, Tito visited Beijing and was welcomed by the Chinese leadership. At this point, the Albanian Party of Labour had declared that China was now a revisionist state akin to the Soviet Union and Yugoslavia, and that Albania was the only Marxist–Leninist state on earth. Hoxha stated:

The Chinese leaders are acting like the leaders of a 'great state.' They think, 'The Albanians fell out with the Soviet Union because they had us, and if they fall with us, too, they will go back to the Soviets,' therefore they say, 'Either with us or the Soviets, it is all the same, the Albanians are done for.' But to hell with them! We shall fight against all this trash, because we are Albanian Marxist–Leninists and on our correct course we shall always triumph![85]

On 13 July 1978, China announced that it was cutting off all aid to Albania. For the first time in modern history, Albania did not have an ally or major trading partner.

Human rights

Certain clauses in the 1976 constitution effectively circumscribed the exercise of political liberties that the government interpreted as contrary to the established order.[86] In addition, the government denied the population access to information other than that disseminated by the government-controlled media. Internally, the Sigurimi followed the repressive methods of the NKVD, MGB, KGB, and the East German Stasi. At one point, every third Albanian had either been incarcerated in labour camps or interrogated by the Sigurimi.[87]

To eliminate dissent, the government imprisoned thousands in forced-labour camps or executed them for crimes such as alleged treachery or for disrupting the proletarian dictatorship. Travel abroad was forbidden after 1968 to all but those on official business. Western European culture was looked upon with deep suspicion, resulting in arrests and bans on unauthorised foreign material.[88] Art was made to reflect the styles of socialist realism.[89] Beards were banned as unhygienic in order to curb the influence of Islam (many Imams and Babas had beards) and the Eastern Orthodox faith.

The justice system regularly degenerated into show trials. An American human rights group described the proceedings of one trial: "... [The defendant] was not permitted to question the witnesses and that, although he was permitted to state his objections to certain aspects of the case, his objections were dismissed by the prosecutor who said, 'Sit down and be quiet. We know better than you.'"[90] In order to lessen the threat of political dissidents and other exiles, relatives of the accused were often arrested, ostracised, and accused of being "enemies of the people".[91] Political executions were common, and as a result at least 5,000 people—possibly as many as 25,000—were killed by the regime.[92][93][94]

Torture was often used to obtain confessions:

One émigré, for example, testified to being bound by his hands and legs for one and a half months, and beaten with a belt, fists or boots for periods of two to three hours every two or three days. Another was detained in a cell one meter by eight meters large in the local police station and kept in solitary confinement for a five-day period punctuated by two beating sessions until he signed a confession; he was taken to Sigurimi headquarters, where he was again tortured and questioned, despite his prior confession, until his three-day trial. Still another witness was confined for more than a year in a three-meter square cell underground. During this time he was interrogated at irregular intervals and subjected to various forms of physical and psychological torture. He was chained to a chair, beaten, and subjected to electric shocks. He was shown a bullet that was supposedly meant for him and told that car engines starting within his earshot were driving victims to their executions, the next of which would be his.[95]

During Hoxha's rule, "[t]here were six institutions for political prisoners and fourteen labour camps where political prisoners and common criminals worked together. It has been estimated that there were approximately 32,000 people imprisoned in Albania in 1985."[96]

Article 47 of the Albanian Criminal Code stated that to "escape outside the state, as well as refusal to return to the Fatherland by a person who has been sent to serve or has been permitted temporarily to go outside the state" was an act of treason, a crime punishable by a minimum sentence of ten years or even death.[97] The Albanian government went to great lengths to prevent defection by fleeing the country:

An electrically-wired metal fence stands 600 meters to one kilometer from the actual border. Anyone touching the fence not only risks electrocution, but also sets off alarm bells and lights which alert guards stationed at approximately one-kilometer intervals along the fence. Two meters of soil on either side of the fence are cleared in order to check for footprints of escapees and infiltrators. The area between the fence and the actual border is seeded with booby traps such as coils of wire, noise makers consisting of thin pieces of metal strips on top of two wooden slats with stones in a tin container which rattle if stepped on, and flares that are triggered by contact, thus illuminating would-be escapees during the night.[98]

Religion

Albania, the only predominantly Muslim country in Europe at that time, largely owing to Turkish influence in the region, had not, like the Ottoman Empire, identified religion with ethnicity. In the Ottoman Empire, Muslims were viewed as Turks, Orthodox Christians were viewed as Greeks, and Roman Catholics were viewed as Latins. Hoxha believed this was a serious issue, feeling that it both fueled Greek separatists in southern Albania and that it also divided the nation in general. The Agrarian Reform Law of 1945 confiscated much of the church's property in the country. Catholics were the earliest religious community to be targeted, since the Vatican was seen as being an agent of Fascism and anti-Communism.[99] In 1946 the Jesuit Order was banned and the Franciscans were banned in 1947 . Decree No. 743 (On religion) sought a national church and forbade religious leaders from associating with foreign powers.

The Party focused on atheist education in schools. This tactic was effective, primarily due to the high birthrate policy encouraged after the war. During holy periods, such as Lent and Ramadan, many forbidden foods (dairy products, meat, etc.) were distributed in schools and factories, and people who refused to eat those foods were denounced. Starting on 6 February 1967, the Party began a new offensive against religion. Hoxha, who had declared a "Cultural and Ideological Revolution" after being partly inspired by China's Cultural Revolution, encouraged communist students and workers to use more forceful tactics to promote atheism, although violence was initially condemned.[100]

According to Hoxha, the surge in anti-religious activity began with the youth. The result of this "spontaneous, unprovoked movement" was the closing of all 2,169 churches and mosques in Albania. State atheism became official policy, and Albania was declared the world's first atheist state. Religiously based town and city names were changed, as well as personal names. During this period religiously based names were also made illegal. The Dictionary of People's Names, published in 1982, contained 3,000 approved, secular names. In 1992, Monsignor Dias, the Papal Nuncio for Albania appointed by Pope John Paul II, said that of the three hundred Catholic priests present in Albania prior to the Communists coming to power, only thirty survived.[101] All religious practices and all clergymen were outlawed and those religious figures who refused to give up their positions were either arrested or forced into hiding.[102]

Cultivating nationalism

Enver Hoxha had declared during the anti-religious campaign that "the only religion of Albania is Albanianism,"[103] a quotation from the poem O moj Shqiperi ("O Albania") by the 19th-century Albanian writer Pashko Vasa.

Muzafer Korkuti, one of the dominant figures in post-war Albanian archaeology and now Director of the institute of Archaeology in Tirana, said this in an interview on 10 July 2002:[104]

Archaeology is part of the politics which the party in power has and this was understood better than anything else by Enver Hoxha. Folklore and archaeology were respected because they are the indicators of the nation, and a party that shows respect to national identity is listened to by other people; good or bad as this may be. Enver Hoxha did this as did Hitler. In Germany in the 1930s there was an increase in Balkan studies and languages and this too was all part of nationalism.

Efforts were focused on an Illyrian-Albanian continuity issue.[104] An Illyrian origin of the Albanians (without denying Pelasgian roots[105]) continued to play a significant role in Albanian nationalism,[106] resulting in a revival of given names supposedly of "Illyrian" origin, at the expense of given names associated with Christianity. At first, Albanian nationalist writers opted for the Pelasgians as the forefathers of the Albanians, but as this form of nationalism flourished in Albania under Enver Hoxha, the Pelasgians became a secondary element[105] to the Illyrian theory of Albanian origins, which could claim some support in scholarship.[107]

The Illyrian descent theory soon became one of the pillars of Albanian nationalism, especially because it could provide some evidence of continuity of an Albanian presence both in Kosovo and in southern Albania, i.e., areas that were subject to ethnic conflicts between Albanians, Serbs and Greeks.[108] Under the government of Enver Hoxha, an autochthonous ethnogenesis[104] was promoted and physical anthropologists[104] tried to demonstrate that Albanians were different from any other Indo-European populations, a theory now disproved.[109] They claimed that the Illyrians were the most ancient people[104][110] in the Balkans and greatly extended the age of the Illyrian language.[104][111]

Later life and death

A new Constitution was decided upon by the Seventh Congress of the Albanian Party of Labour on 1–7 November 1976. According to Hoxha, "The old Constitution was the Constitution of the building of the foundations of socialism, whereas the new Constitution will be the Constitution of the complete construction of a socialist society."[112]

Self-reliance was now stressed more than ever. Citizens were encouraged to train in the use of weapons, and this activity was also taught in schools. This was to encourage the creation of quick partisans.[113]

Borrowing and foreign investment were banned under Article 26 of the Constitution, which read: "The granting of concessions to, and the creation of foreign economic and financial companies and other institutions or ones formed jointly with bourgeois and revisionist capitalist monopolies and states as well as obtaining credits from them are prohibited in the People's Socialist Republic of Albania."[114] Hoxha said of borrowing money and allowing investment from other countries:

No country whatsoever, big or small, can build socialism by taking credits and aid from the bourgeoisie and the revisionists or by integrating its economy into the world system of capitalist economies. Any such linking of the economy of a socialist country with the economy of bourgeois or revisionist countries opens the doors to the actions of the economic laws of capitalism and the degeneration of the socialist order. This is the road of betrayal and the restoration of capitalism, which the revisionist cliques have pursued and are pursuing.[115]

During this period Albania was the most isolated and poorest country in Europe and socially backwards by European standards. It had the lowest standard of living in Europe.[116] As a result of economic self-sufficiency, Albania had a minimal foreign debt. In 1983, Albania imported goods worth $280 million but exported goods worth $290 million, producing a trade surplus of $10 million.[117]

In 1981, Hoxha ordered the execution of several party and government officials in a new purge. Prime Minister Mehmet Shehu, the second-most powerful man in Albania and Hoxha's closest comrade-in-arms for 40 years, was reported to have committed suicide in December 1981. He was subsequently condemned as a "traitor" to Albania, and was also accused of operating in the service of multiple intelligence agencies. It is generally believed that he was either killed or shot himself during a power struggle or over differing foreign policy matters with Hoxha.[118] Hoxha also wrote a large assortment of books during this period, resulting in over 65 volumes of collected works, condensed into six volumes of selected works.[119]

Hoxha suffered a heart attack in 1973 from which he never fully recovered. In increasingly precarious health from the late 1970s onward, he turned most state functions over to Ramiz Alia. In his final days he was bound to a wheelchair and suffering from diabetes, which had developed in 1948, and cerebral ischemia, from which he had suffered since 1983. On 9 April 1985, he was struck by a massive ventricular fibrillation. All efforts to reverse it failed, and he died in the early morning of 11 April 1985.[120]

Hoxha's death left Albania with a legacy of isolation and fear of the outside world. Despite some economic progress made by Hoxha,[121] the country was in economic stagnation; Albania had been the poorest European country throughout much of the Cold War period. Following the transition to capitalism in 1992, Hoxha's legacy diminished, so that by the early 21st century very little of it was still in place in Albania.

Family

The surname Hoxha is the Albanian variant of Hodja (Template:Lang-fa khawājah, Template:Lang-tr), a title given to his ancestors due to their efforts to teach Albanians about Islam.[122] In addition, among the population he was widely known by his nickname of Dulla, a short form for the Muslim name Abdullah stemming from his Muslim roots.[citation needed]

Hoxha's parents were Halil and Gjylihan (Gjylo) Hoxha, and Hoxha had three sisters named Fahrije, Haxhire and Sanije. Hysen Hoxha ([hyˈsɛn ˈhɔdʒa]) was Enver Hoxha's uncle and was a militant who campaigned vigorously for the independence of Albania, which occurred when Enver was four years old. His grandfather Beqir was involved in the Gjirokastër section of the League of Prizren.[123]

Hoxha's son Sokol Hoxha was the CEO of the Albanian Post and Telecommunication service and is married to Liliana Hoxha.[124] The later democratic president of Albania Sali Berisha was often seen socializing with Sokol Hoxha and other close relatives of leading communist figures in Albania.[125]

Hoxha's daughter, Pranvera, is an architect. Along with her husband, Klement Kolaneci, she designed the Enver Hoxha Museum in Tirana, a white-tiled pyramid. Some sources have referred to the edifice, said to be the most expensive ever constructed in Albanian history, as the "Enver Hoxha Mausoleum," though this was not an official appellation. The museum opened in 1988, three years after her father's death, and in 1991 was transformed into a conference center and exhibition venue renamed Pyramid of Tirana.[126]

Assassination attempts

Banda Mustafaj was a group of four Albanian emigres, led by Xhevdet Mustafa, who wanted to assassinate Enver Hoxha in 1982. The plan failed and two of its members were killed and another one was arrested.[127][128] It marked the only real effort to kill Hoxha.[129][130]

Works

- Speeches (1961–1962). The "8 Nëntori" Publishing House, Tirana, 1977.

- Speeches and articles (1963–1964). The "8 Nëntori" Publishing House, Tirana, 1977.

- Speeches, conversations and articles (1965–1966). The "8 Nëntori" Publishing House, Tirana, 1977.

- Speeches, conversations and articles (1967–1968). The "8 Nëntori" Publishing House, Tirana, 1978.

- Speeches, conversations and articles (1969–1970). The "8 Nëntori" Publishing House, Tirana, 1980.

- Selected works. Six volumes, The "8 Nëntori" Publishing House, Tirana, 1974–1987.

- Reflections on China. Two volumes, The "8 Nëntori" Publishing House, Tirana, 1979.

- Two Friendly Peoples. The "8 Nëntori" Publishing House, Tirana, 1985.

- The Superpowers. The "8 Nëntori" Publishing House, Tirana, 1986.

In popular culture

- On their 1986 album The Unacceptable Face of Freedom, London industrial band Test Dept. wrote a song entitled "Comrade Enver Hoxha".

- In the 2006 film Inside Man bank robbers foil police attempts to eavesdrop by playing an Enver Hoxha speech near surveillance devices.

- In 2012, Hoxha's first name (ENVER) engraved on the Shpiragu mountain was changed to "NEVER" by artist Armando Lulaj.

- In The Simpsons episode "The Crepes of Wrath" the character Adil is from Albania and has the surname of Hoxha.

- American punk band Cleveland Bound Death Sentence has on their self-titled album (Lookout Records) an HOXHA song; lyrics include: enter HOXHA / head of CCCPA / No more Zog / No more Emmanual III / Independent Albania under a single Party.

- The 2001 Jack Higgins novel The Keys of Hell is set in Hoxha's Albania and mentions him many times.

- Les 71 Oeuvres http://www.albanianpavilion.org, is the new work by Armando Lulaj who intervened on the 71 books that the leader Enver Hoxha has written and rewritten until the end of his life. This project was part of the Albanian Pavilion in the Venice Biennale, 2015.

- In The Gladiator, the fifth novel in Harry Turtledove's "Crosstime Traffic" alternate history series, the main characters attend a high school called Enver Hoxha Polytechnic in Milan, Italian People's Republic, in a world where all countries are subject to a still-existing USSR in the 2090s.

See also

- Albanian Resistance of World War II

- Autarky

- Hoxhaism

- History of Albania

- Pyramid of Tirana

- National Martyrs Cemetery of Albania

References

- ^ There is uncertainty over Hoxha's true date of birth. Fevziu (2016), p. 10) notes: "No fewer than five different dates are to be found in the Central State Archives [of Albania] alone."

- ^ "Varja e Havzi Nelës, PD zbardh vendimin dhe firmën e Kristaq Ramës". Retrieved 14 January 2016.

- ^ "KLOSI – Poeti disident Havzi Nela..." Klosi News.

- ^ "Lajmi Shqip".

- ^ 40 Years of Socialist Albania, Dhimiter Picani

- ^ Biography of Baba Rexheb: "[Enver Hoxha was] from the Gjirokastër area and [he] came from [a family] that [was] attached to the Bektashi tradition. In fact, fourteen years before Enver set off for France to study, his father brought him to seek the blessing of Baba Selim. The baba (dervish) was not one to refuse the request of a petitioner and he made a benediction over the boy."

- ^ O'Donnell 1999, p. 193.

- ^ Hamm, Harry. Albania – China's Beachhead in Europe. New York: Frederick A. Praeger, Inc. (1963), pp. 84, 93.

- ^ O'Donnell 1999, p. 196, where he is described as "by far the best-read head of state in Eastern Europe."

- ^ See note 1 on page 32 of the Selected Works of Enver Hoxha: Volume I (Tirana: 8 Nëntori Publishing House) p. 32.

- ^ See page 34 and also note 2 on page 35 of the Selected Works of Enver Hoxha: Volume I.

- ^ John E. Jessup, An Encyclopaedic Dictionary of Conflict and Conflict Resolution, 1945–1996. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press. 1998. p. 288. "At the time of the Italian invasion of Albania, he was fired for refusing to join the Albanian Fascist Party and became a tobacconist in the capital city, Tirana."

- ^ The Albanians: An Ethnographic History from Prehistoric Times to the Present Vol. II, Edwin E. Jacques, North Carolina 1995, p. 416.

- ^ See note 1 on page 3 of the Selected Works of Enver Hoxha: Volume I (Tirana: 8 Nentori Publishing House, 1974) p. 3.

- ^ Enver Hoxha, "Report Delivered to the 1st Consultative Meeting of the Activists of the Communist Party of Albania" contained in the Selected Works of Enver Hoxha: Volume I, pp. 3–30.

- ^ Enver Hoxha, "Call to the Albanian Peasantry" contained in the Selected Works of Enver Hoxha: Volume I, pp. 31–38.

- ^ Enver Hoxha, "Call to the Albanian Peasantry" contained in the Selected Works of Enver Hoxha: Volume I, p. 36.

- ^ Of Enver Hoxha And Major Ivanov, New York Times, 28 April 1985

- ^ Bernd J Fischer. "Resistance in Albania during the Second World War: Partisans, Nationalists and the S.O.E.", East European Quarterly 25 (1991)

- ^ Enver Hoxha, "Letter from the Central Committee of the Communist Party of Albania to the Vlora Regional Committee of the Communist Party of Albania" dated 17 August 1943 contained in the Selected Works of Enver Hoxha: Volume I, pp. 167–168.

- ^ O'Donnell 1999, p. 9.

- ^ Nora Beloff, Tito's Flawed Legacy (Boulder: Westview Press, 1985), 192.

- ^ O'Donnell 1999, pp. 10–1; Jacques, pp. 421–423.

- ^ O'Donnell 1999, p. 12.

- ^ Jacques. p. 433. Miranda Vickers. The Albanians: A Modern History. New York: I.B. Tauris, 2000. p. 164.

- ^ Taylor & Francis Group (September 2004). Europa World Year. Taylor & Francis. p. 441. ISBN 978-1-85743-254-1. Retrieved 10 January 2012.

- ^ Enver Hoxha, Selected Works, 1941–1948, vol. I (Tirana: 8 Nëntori Publishing House, 1974, 599–600.

- ^ Ramadan Marmullaku, Albania and the Albanians, trans. Margot and Bosko Milosavljević (Hamden, Connecticut: Archon Books, 1975, 93–94.

- ^ Library of Congress Country Studies

- ^ Gjonça, Arjan. Communism, Health, and Lifestyle: The Paradox of Mortality Transition in Albania, 1950–1990. Connecticut: Greenwood Press, 2001., p. 15. "20.1% of the population was infected."

- ^ a b Cikuli, Health Care in the People's Republic of Albania, p. 33.

- ^ Jacques, p. 473.

- ^ a b O'Donnell 1999, p. 19.

- ^ See Nicholas C. Pano, The People's Republic of Albania (Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins Press, 1968), 101.

- ^ H. Banja and V. Toçi, Socialist Albania on the Road to Industrialization (Tirana: 8 Nëntori Publishing House, 1979), 66. "... Albania didn't need to create its national industry, but should limit her production to agricultural and mineral raw materials, which were to be sent for industrial processing to Yugoslavia. In other words, they wanted the Albanian economy to be a mere appendage of the Yugoslav economy."

- ^ Ranko Petković, "Yugoslavia and Albania," in Yugoslav-Albanian Relations, trans. Zvonko Petnicki and Darinka Petković (Belgrade: Review of International Affairs, 1984, 274–275.

- ^ Enver Hoxha, With Stalin (Tirana: 8 Nëntori Publishing House, 1979, 92.

- ^ a b O'Donnell 1999, p. 22.

- ^ Jacques, p. 467.

- ^ Fevziu 2016, p. 146.

- ^ The Economist 179 (16 June 1956): 110.

- ^ On the "socialist division of labor" see: The International Socialist Division of Labor (7 June 1962), German History in Documents and Images.

- ^ The Institute of Marxist–Leninist Studies at the Central Committee of the Party of Labour of Albania. History of the Party of Labor of Albania, 2nd ed. Tiranë: 8 Nëntori Publishing House, 1982. p. 296.

- ^ William Griffith, Albania and the Sino-Soviet Rift, p. 22

- ^ Biberaj 1986, p. 27.

- ^ O'Donnell 1999, p. 46.

- ^ O'Donnell 1999, pp. 46–7

- ^ Khrushchev Remembers, trans. Strobe Talbott (Boston: Little Brown and Co., 1970), 475–476

- ^ https://www.marxists.org/reference/archive/hoxha/works/1976/khruschevites/13.htm

- ^ Albania Challenges Khrushchev Revisionism (New York: Gamma Publishing, 1976), 109–110n. Enver Hoxha stated: "This ridiculous action of Koço Tashko made it quite evident that the text of his contribution had been dictated by an official of the Soviet Embassy and during the translation he had become confused, failing to distinguish between the text and the punctuation marks."

- ^ The Institute of Marxist–Leninist Studies at the Central Committee of the Party of Labour of Albania. p. 359. "... the Albanian people and their Party of Labour will even live on grass if need be, but they will never sell themselves 'for 30 pieces of silver', ... They would rather die honourably on their feet than live in shame on their knees."

- ^ Enver Hoxha. "Imperialism and the Revolution".

- ^ Kanuni i Lekë Dukagjinit [The Code of Lekë Dukagjini] (Prishtinë, Kosove: Rilindja, 1972): bk. 3, chap. 5, no. 29, 38.

- ^ Kanuni i Lekë Dukagjinit [The Code of Lekë Dukagjini], bk. 10, chap. 22, no. 130, secs. 936–937, 178.

- ^ Harilla Papajorgi, Our Friends Ask (Tirana: The Naim Frashëri Publishing House, 1970), 130.

- ^ Ksanthipi Begeja, The Family in the People's Socialist Republic of Albania, (Tirana: 8 Nëntori Publishing House, 1984), 61.

- ^ Jacques, p. 557.

- ^ The Directorate of Statistics at the State Planning Commission, 35 Years of Socialist Albania (Tirana: 8 Nëntori Publishing House, 1981), 129.

- ^ Anton Logoreci, The Albanians: Europe's Forgotten Survivors (Boulder: Westview Press, 1977), 158.

- ^ An Outline of the People's Socialist Republic of Albania. Tirana: The 8 Nëntori Publishing House, 1978.

- ^ Pollo and Puto, The History of Albania, p. 280.

- ^ Vickers, p. 224.

- ^ Mehmet Shehu, "The Magnificent Balance of Victories in the Course of 35 Years of Socialist Albania", Speech (Tirana: 8 Nëntori Publishing House, 1979), p. 21.

- ^ Albania's Chemical Cache Raises Fears About Others – The Washington Post, Monday 10 January 2005, Page A01

- ^ Radio Free Europe Research 17 December 1979 quoting Hoxha's Reflections on China Volume II: "In Pyongyang, I believe that even Tito will be astonished at the proportions of the cult of his host, which has reached a level unheard of anywhere else, either in past or present times, let alone in a country which calls itself socialist."

- ^ Kosta Koçi, interview with James S. O'Donnell, A Coming of Age: Albania under Enver Hoxha, Tape recording, Tirana, 12 April 1994.

- ^ "ODM of Albania: Title "Mother Heroine"".

- ^ William Ash. Pickaxe and Rifle: The Story of the Albanian People. London: Howard Baker Press Ltd. 1974. p. 238.

- ^ Albania – ABORTION POLICY – United Nations

- ^ Enver Hoxha. The Khrushchevites. Tirana: 8 Nëntori Publishing House. 1980. pp. 231–234, 240–250.

- ^ Biberaj 1986, p. 40.

- ^ a b Hamm, 45.

- ^ Owen Pearson. Albania in the Twentieth Century: A History Vol. III. New York: St. Martin's Press. 2006. p. 628.

- ^ Biberaj 1986, p. 48.

- ^ "Sino-Albanian Joint Statement," Peking Review (17 January 1964) 17.

- ^ a b O'Donnell 1999, p. 68.

- ^ Biberaj 1986, p. 49.

- ^ Hamm, 43.

- ^ Biberaj 1986, p. 58.

- ^ Enver Hoxha, Selected Works: 1966–1975, vol. 4 (Tirana: 8 Nëntori Publishing House, 1982), 666–667, 668.

- ^ Biberaj 1986, p. 90.

- ^ Enver Hoxha, Reflections on China, vol. 2: (Toronto: Norman Bethune Institute, 1979), 41.

- ^ Biberaj 1986, pp. 98–9.

- ^ Enver Hoxha, Reflections on China, vol. 2: (Toronto: Norman Bethune Institute, 1979), 656.

- ^ Enver Hoxha, Reflections on China, vol. 2. (Toronto: Norman Bethune Institute, 1979), 107

- ^ O'Donnell 1999, p. 129.

- ^ Raymond E. Zickel & Walter R. Iwaskiw. Albania: A Country Study. Washington, D.C.: Federal Research Division of the United States Library of Congress. p. 235.

- ^ Dance fever reaches Albania "The former student, now the mayor of Tirana, said that he would cower beneath the bedclothes at night listening to foreign radio stations, an activity punishable by a long stretch in a labour camp. He became fascinated by the saxophone. Yet, as such instruments were considered to be an evil influence and were banned, he had never seen one. "

- ^ Keefe, Eugene K. Area Handbook for Albania. Washington, D.C.: The American University (Foreign Area Studies), 1971.

- ^ Minnesota International Human Rights Committee, Human Rights in the People's Socialist Republic of Albania. (Minneapolis: Minnesota Lawyers International Human Rights Committee, 1990), 46.

- ^ James S. O'Donnell, "Albania's Sigurimi: The ultimate agents of social control" Problems of Post-Communism #42 (Nov/Dec 1995): 5p.

- ^ 15 Feb 1994 Washington Times

- ^ "WHPSI": The World Handbook of Political and Social Indicators by Charles Lewis Taylor

- ^ 8 July 1997 NY Times

- ^ Minnesota International Human Rights Committee, 46–47.

- ^ O'Donnell 1999, p. 134.

- ^ Minnesota International Human Rights Committee, p. 136.

- ^ Minnesota International Human Rights Committee, 50–53.

- ^ Anton Logoreci, The Albanians: Europe's Forgotten Survivors (Boulder: Westview Press, 1977), 154.

- ^ Enver Hoxha, "The Communists Lead by Means of Example, Sacrifices, Abnegation: Discussion in the Organization of the Party, Sector C, of the 'Enver' Plant", 2 March 1967, in Hoxha, E., Vepra, n. 35, Tirana, 1982, pp. 130–1. "In this matter violence, exaggerated or inflated actions must be condemned. Here it is necessary to use persuasion and only persuasion, political and ideological work, so that the ground is prepared for each concrete action against religion."

- ^ Henry Kamm, "Albania's Clerics Lead a Rebirth," New York Times, 27 March 1992, p. A3.

- ^ Jacques, p. 489, 495.

- ^ One World Divisible: A Global History Since 1945 (The Global Century Series) by David Reynolds, 2001, page 233: "... the country." Henceforth, Hoxha announced, the only religion would be "Albanianism. ... "

- ^ a b c d e f "Archaeology Under Dictatorship".

- ^ a b Stephanie Schwandner-Sievers, Bernd Jürgen Fischer, Albanian Identities: Myth and History, Indiana University Press, 2002, ISBN 978-0-253-34189-1, page 96, "but when Enver Hoxha declared that their origin was Illyrian (without denying their Pelasgian roots), no one dared participate in further discussion of the question".

- ^ ISBN 978-960-210-279-4 Miranda Vickers, The Albanians Chapter 9. "Albania Isolates itself" page 196, "From time to time the state gave out lists with pagan, supposed Illyrian or newly constructed names that would be proper for the new generation of revolutionaries."

- ^ Madrugearu A, Gordon M. The wars of the Balkan peninsula. Rowman & Littlefield, 2007. p.146.

- ^ Stephanie Schwandner-Sievers, Bernd Jürgen Fischer, Albanian Identities: Myth and History, Indiana University Press, 2002, ISBN 978-0-253-34189-1, p. 118.

- ^ Belledi et al. (2000) Maternal and paternal lineages in Albania and the genetic structure of Indo-European populations

- ^ The Balkans – a post-communist history by Robert Bideleux & Ian Jeffries, Routledge, 2007, ISBN 978-0-415-22962-3, page 23, "they thus claim to be the oldest indigenous people of the western Balkans".

- ^ The Balkans – a post-communist history by Robert Bideleux & Ian Jeffries, Routledge, 2007, ISBN 978-0-415-22962-3, page 26.

- ^ Enver Hoxha, Report on the Activity of the Central Committee of the Party of Labour of Albania (Tirana: 8 Nëntori Publishing House, 1977), 12.

- ^ Letter from Albania: Enver Hoxha's legacy, and the question of tourism: "The bunkers were just one component of Hoxha's aim to arm the entire country against enemy invaders. Gun training used to be a part of school, I was told, and every family was expected to have a cache of weapons. Soon, Albania became awash in guns and other armaments – and the country is still dealing with that today, not just in its reputation as a center for weapons trading but in its efforts to finally decommission huge stockpiles of ammunition as part of its new NATO obligations."

- ^ Biberaj 1986, 162n.

See also The Albanian Constitution of 1976. - ^ Hoxha, Report on the Activity of the Central Committee of the Party of Labour of Albania, 8.

- ^ "On Eagle's Wings".

- ^ The Directorate of the Intelligence of the Central Intelligence Agency, The World Factbook (Washington: Government Printing Office, 1986), 3.

- ^ O'Donnell 1999, pp. 198–201; Vickers, pp. 207–208. Jacques, pp. 510–512.

- ^ NYtimes.com "Hoxha, who died in 1985, was one of the most verbose statesmen of modern times and pressed more than 50 volumes of opinions, diaries and dogma on his long-suffering people, the poorest in Europe."

- ^ Jacques, p. 520. "... there was a detailed medical report by a distinguished medical team. Enver Hoxha had suffered since 1948 with diabetes which gradually caused widespread damage to the blood vessels, heart, kidneys and certain other organs. In 1973, as a consequence of this damage, a myocardial infarction occurred with rhythmic irregularity. During the following years a serious heart disorder developed. On the morning of 9 April 1985, an unexpected ventricular fibrillation occurred. Despite intensive medication, repeated fibrillation and its irreversible consequences in the brain and kidneys caused death at 2:15 am on 11 April 1985."

- ^ O'Donnell 1999, p. 186: "On the positive side, an objective analysis must conclude that Enver Hoxha's plan to mobilize all of Albania's resources under the regimentation of a central plan was effective and quite successful ... Albania was a tribal society, not necessarily primitive but certainly less developed than most. It had no industrial or working class tradition and no experience using modern production techniques. Thus, the results achieved, especially during the phases of initial planning and construction of the economic base were both impressive and positive."

- ^ "Ju Tregoj Pemën e Familjes të Enver Hoxhës", Tirana Observer 15 June 2007

- ^ Pero Zlatar. Albanija u eri Envera Hoxhe Vol. II. Zagreb: Grafički zavod Hrvatske. 1984. pp. 23–24.

- ^ Liliana Hoxha personal website. 25 February 2010.

- ^ [1] Archived 2012-03-26 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Wheeler, Tony (2010). Lonely Planet Badlands: A Tourist on the Axis of Evil. Victoria: Lonely Planet. pp. 49–50. ISBN 978-1-74220-104-7. Retrieved 12 March 2011.

- ^ "Zbulohen dokumentet e CIA-s dhe FBI-se per Xhevdet Mustafen". Shqiperia.com. Retrieved 13 November 2012.

- ^ "Zbuluesi ushtarak: Xhevdet Mustafa do vendoste monarkinë". Zeriikosoves.org. Retrieved 13 November 2012.

- ^ "Xhevdet Mustafa, sot 29 vite nga zbarkimi në Divjakë, zbulohet biseda me kunatin e Hazbiut Panorama". Lajme4.shqiperia.com. 25 September 2011. Retrieved 13 November 2012.

- ^ "Rrëfimi i Halit Bajramit: Unë, njeriu i Hazbiut në bandën e Xhevdet Mustafës Panorama". Lajme4.shqiperia.com. 12 August 2011. Retrieved 13 November 2012.

Further reading

- Banja H. and V. Toçi, Socialist Albania on the Road to Industrialization, Tirana: 8 Nëntori Publishing House, 1979

- Beloff, Nora. Tito's Flawed Legacy, Boulder: Westview Press, 1985, ISBN 978-0-575-03668-0

- Biberaj, Elez (1986). Albania And China: A Study Of An Unequal Alliance. Boulder, CO: Westview Press. ISBN 978-0-813-37230-3.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Cikuli, Zisa. Health Care in the People's Republic of Albania 1984

- Fevziu, Blendi (2016). Enver Hoxha: The Iron Fist of Albania. London: I.B.Tauris. ISBN 978-1-784-53485-1.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Gjonça, Arjan. Communism, Health, and Lifestyle: The Paradox of Mortality Transition in Albania, 1950–1990. CT: Greenwood Press, 2001. ISBN 978-0-313-31586-2

- Hamm, Harry. Albania – China's Beachhead in Europe, New York: Frederick A. Praeger, Inc., 1963.

- Hoxha, Enver. Selected Works, 1941–1948, vol. I, Tirana: 8 Nëntori Publishing House, 1974.

- The Institute of Marxist-Leninist Studies at the Central Committee of the Party of Labour of Albania. History of the Party of Labor of Albania, 2nd ed. Tiranë: 8 Nëntori Publishing House, 1982.

- Jacques, Edwin E. The Albanians: An Ethnographic History from Prehistoric Times to the Present Vol. II, North Carolina 1995, ISBN 978-0-7864-4238-6

- Jessup, John E. An Encyclopedic Dictionary of Conflict and Conflict Resolution, 1945–1996. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press. 1998, ISBN 978-0-313-28112-9

- Marmullaku, Ramadan. Albania and the Albanians, trans. Margot and Bosko Milosavljević, Hamden, CT: Archon Books, 1975

- Myftaraj, Kastriot. The Enigmas of Enver Hoxha's Domination 1944–1961, Tirana 2009, ISBN 978-99956-57-10-9

- Myftaraj, Kastriot. The Secret Life of Enver Hoxha, 1908–1944, Tirana 2008, ISBN 978-99956-706-4-1

- O'Donnell, James S. (1999). A Coming of Age: Albania under Enver Hoxha (PDF). East European Monographs. New York, NY: Columbia University Press. ISBN 978-0-88033-415-0.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Pearson, Owen S. and I.B. Tauris. Albania in Occupation and War, London 2006, ISBN 978-1-84511-104-5

- Pano, Nicholas C. The People's Republic of Albania, Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins Press, 1968

- Pipa, Arshi, Albanian Stalinism, Boulder: East European Monographs, 1990, ISBN 978-0-88033-184-5

External links

- Enver Hoxha Reference Archive at marxists.org

- English collection of some of Hoxha's works

- Another English collection of some of Hoxha's works

- A Russian site with the works of Enver Hoxha

- Enver Hoxha tungjatjeta

- Disa nga Veprat e Shokut Enver Hoxha

- Albanian.com article on Hoxha

- Virtual Memory Museum Official Website

- Enver Hoxha's Underground Bunker Official Website

- "Albania: Stalin's heir", TIME, 22 December 1961

- Enver Hoxha

- 1908 births

- 1985 deaths

- Albanian anti-fascists

- Albanian atheists

- Albanian communists

- Albanian former Muslims

- Albanian generals

- Albanian National Lyceum alumni

- Albanian nationalists

- Albanian people of World War II

- Albanian resistance members

- Albanian revolutionaries

- Anti-Revisionists

- Antitheists

- Atheism activists

- Communist rulers

- Critics of religions

- Heroes of Albania

- International opponents of apartheid in South Africa

- Male feminists

- Natalism

- Opposition to Islam in Europe

- Party of Labour of Albania politicians

- People from Gjirokastër

- People from Janina Vilayet

- People's Socialist Republic of Albania

- Prime Ministers of Albania

- Recipients of the Order of Lenin

- Recipients of the Order of Suvorov, 1st class

- Religious persecution

- University of Montpellier alumni

- University of Paris alumni

- World War II resistance members

- Defence ministers of Albania