Faiyum

Faiyum

الفيوم | |

|---|---|

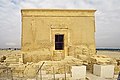

Clockwise from top: a small fishing boat on Lake Qarun, Qasr Qarun, trees fighting desertification, Sabil Ali-Bek, Tanta Overview | |

| Coordinates: 29°18′30″N 30°50′39″E / 29.308374°N 30.844105°E | |

| Country | |

| Governorate | Faiyum |

| Elevation | 23 m (75 ft) |

| Population (2012) | |

| • Total | 349,883 |

| Time zone | UTC+2 (EET) |

The Faiyum (Arabic: الفيوم el-Fayyūm pronounced [elfæjˈjuːm], borrowed from Coptic: ̀Ⲫⲓⲟⲙ or Ⲫⲓⲱⲙ Phiom or Phiōm from Ancient Egyptian: pꜣ ym "the Sea, Lake") is a city in Middle Egypt. Located 100 kilometres (62 miles) southwest of Cairo, in the Faiyum Oasis, it is the capital of the modern Faiyum Governorate. Originally called Shedet in Egyptian, the Greeks called it Koinē Greek: Κροκοδειλόπολις Krokodilópolis, the Romans Arsinoë.[1] It is one of Egypt's oldest cities due to its strategic location.[1]

Name and etymology

| |||||||

| pꜣ-ymꜥ in hieroglyphs | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Its name in English is also spelled as Fayum, Faiyum or El Faiyūm. Faiyum was previously officially named Madīnet El Faiyūm (Arabic for The City of Faiyum). The name Faiyum (and its spelling variations) may also refer to the Faiyum Oasis, although it is commonly used by Egyptians today to refer to the city.[2][3]

The modern name of the city comes from Coptic ̀Ⲫⲓⲟⲙ /Ⲡⲉⲓⲟⲙ epʰiom/peiom (whence the proper name Ⲡⲁⲓⲟⲙ payom), meaning the Sea or the Lake, which in turn comes from late Egyptian pꜣ-ymꜥ of the same meaning, a reference to the nearby Lake Moeris; the extinct elephant ancestor Phiomia was named after it.

Ancient history

Archaeological evidence has found occupations around the Fayum dating back to at least the Epipalaeolithic. Middle Holocene occupations of the area are most widely studied on the north shore of Lake Moeris, where Gertrude Caton Thompson and Elinor Wight Gardner did a number of excavations of Epipalaeolithic and Neolithic sites, as well as a general survey of the area.[4] Recently the area has been further investigated by a team from the UCLA/RUG/UOA Fayum Project.[5][6]

In ancient Egypt, the city was called Shedet.[1] The 10th-century Bible exegete, Saadia Gaon, thought el-Fayyum to have actually been the biblical city of Pithom, mentioned in Exodus 1:11.[7] It was the most significant centre of the cult of the crocodile god Sobek (borrowed from the Demotic pronunciation as Koinē Greek: Σοῦχος Soûkhos, and then into Latin as Suchus). In consequence, the Greeks called it "Crocodile City" (Koinē Greek: Κροκοδειλόπολις Krokodeilópolis), which was borrowed into Latin as Crocodīlopolis. The city worshipped a tamed sacred crocodile called in Koine Petsuchos, "the Son of Soukhos", that was adorned with gold and gem pendants. The Petsoukhos lived in a special temple pond and was fed by the priests with food provided by visitors. When Petsuchos died, it was replaced by another.[8][9]

Under the Ptolemaic Kingdom, the city was for a while called Ptolemais Euergétis (Koinē Greek: Πτολεμαὶς Εὐεργέτις).[10] Ptolemy II Philadelphus (309–246 BC) renamed the city Arsinoë and the whole nome after the name of his sister-wife Arsinoe II (316–270 or 268), who was deified after her death as part of the Ptolemaic cult of Alexander the Great, the official religion of the kingdom.[11]

Under the Roman Empire, Arsinoë became part of the province of Arcadia Aegypti. To distinguish it from other cities of the same name, it was called "Arsinoë in Arcadia".

With the arrival of Christianity, Arsinoë became the seat of a bishopric, a suffragan of Oxyrhynchus, the capital of the province and the metropolitan see. Michel Le Quien gives the names of several bishops of Arsinoë, nearly all of them associated with one heresy or another.[12]

The Catholic Church, considering Arsinoë in Arcadia to be no longer a residential bishopric, lists it as a titular see.[13]

Fayyum was the seat of Shahralanyozan, governor of the Sasanian Egypt (619–629).[14]

Faiyum mummy portraits

Faiyum is the source of some famous death masks or mummy portraits painted during the Roman occupation of the area. The Egyptians continued their practice of burying their dead, despite the Roman preference for cremation. While under the control of the Roman Empire, Egyptian death masks were painted on wood in a pigmented wax technique called encaustic—the Faiyum mummy portraits represent this technique.[15] While previously believed to represent Greek settlers in Egypt,[16][17] modern studies conclude that the Faiyum portraits instead represent mostly native Egyptians, reflecting the complex synthesis of the predominant Egyptian culture and that of the elite Greek minority in the city.[18][19][20]

Modern city

Faiyum has several large bazaars, mosques,[21] baths and a much-frequented weekly market.[22] The canal called Bahr Yussef runs through the city, its banks lined with houses. There are two bridges over the river: one of three arches, which carries the main street and bazaar, and one of two arches, over which is built the Qaitbay mosque,[22] that was a gift from his wife to honor the Mamluk Sultan in Fayoum. Mounds north of the city mark the site of Arsinoe, known to the ancient Greeks as Crocodilopolis, where in ancient times the sacred crocodile kept in Lake Moeris was worshipped.[22][23] The center of the city is on the canal, with four waterwheels that were adopted by the governorate of Fayoum as its symbol; their chariots and bazaars are easy to spot.

Main sights

- Hanging Mosque, built under the Ottoman Rule over Egypt

- Hawara, archeological site 27 km (17 mi) from the city

- Lahun Pyramids, 4 km (2 mi) outside the city

- Qaitbay Mosque, in the city, and was built by the wife of the Mamluk Sultan Qaitbay

- Qasr Qarun, 44 km (27 mi) from the city

- Wadi Elrayan or Wadi Rayan, the largest waterfalls in Egypt, around 50 km (31 mi) from the city

- Wadi Al-Hitan or Valley of whales, a paleontological site in the Al Fayyum Governorate, some 150 km (93 mi) southwest of Cairo. It is a UNESCO World Heritage Site.

Climate

Köppen-Geiger climate classification system classifies its climate as hot desert (BWh).

The highest record temperatures was 46 °C (115 °F) on June 13, 1965 and the lowest record temperature was 2 °C (36 °F) on January 8, 1966.[24]

| Climate data for Faiyum | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 28 (82) |

30 (86) |

36 (97) |

41 (106) |

43 (109) |

46 (115) |

41 (106) |

43 (109) |

39 (102) |

40 (104) |

36 (97) |

30 (86) |

46 (115) |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 18.9 (66.0) |

20.9 (69.6) |

24.1 (75.4) |

29 (84) |

33.6 (92.5) |

35.5 (95.9) |

36.1 (97.0) |

35.8 (96.4) |

33.2 (91.8) |

30.7 (87.3) |

25.7 (78.3) |

20.4 (68.7) |

28.7 (83.6) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 11.6 (52.9) |

13.2 (55.8) |

16.1 (61.0) |

20.4 (68.7) |

24.9 (76.8) |

27.1 (80.8) |

28.2 (82.8) |

28.1 (82.6) |

25.7 (78.3) |

23.1 (73.6) |

18.6 (65.5) |

13.5 (56.3) |

20.9 (69.6) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | 4.3 (39.7) |

5.5 (41.9) |

8.2 (46.8) |

11.8 (53.2) |

16.3 (61.3) |

18.8 (65.8) |

20.3 (68.5) |

20.4 (68.7) |

18.2 (64.8) |

15.6 (60.1) |

11.6 (52.9) |

6.6 (43.9) |

13.1 (55.6) |

| Record low °C (°F) | 2 (36) |

4 (39) |

5 (41) |

8 (46) |

11 (52) |

16 (61) |

13 (55) |

13 (55) |

10 (50) |

11 (52) |

4 (39) |

4 (39) |

2 (36) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 1 (0.0) |

1 (0.0) |

1 (0.0) |

1 (0.0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

1 (0.0) |

2 (0.1) |

7 (0.1) |

| Source 1: Climate-Data.org[25] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: Voodoo Skies[24] for record temperatures | |||||||||||||

Notable people

- Tefta Tashko-Koço, well known Albanian singer was born in Faiyum, where her family lived at that time.

- Saadia Gaon, the influential Jewish teacher of the early 10th century, was originally from Faiyum, and often called al-Fayyumi.

- Youssef Wahbi, a notable Egyptian actor, well known for his influence on the development of Egyptian cinema and theater.

Gallery

-

Qarun Palace

-

Temple

-

A whale skeleton lies in the sand at Wadi Al-Hitan (Arabic: وادي الحيتان, "Whales Valley") near the city of Faiyum

See also

- Bahr Yussef

- Book of the Faiyum

- Fayum alphabet

- Faiyum Governorate

- Faiyum mummy portraits

- Lake Moeris

- Phiomia (an extinct relative of the elephant, named after Faiyum)

- Nash Papyrus

- Roman Egypt

- Wadi Elrayan

References

- ^ a b c Paola Davoli (2012). "The Archaeology of the Fayum". In Riggs, Christina (ed.). The Oxford Handbook of Roman Egypt. Oxford University Press. pp. 152–153. ISBN 9780199571451.

- ^ "The name of the Fayum province. Katholieke Universiteit Leuven". Trismegistos.org. Archived from the original on 2012-02-29. Retrieved 2013-01-15.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Faiyum. Eternal Egypt". Eternalegypt.org. Archived from the original on 2012-02-13. Retrieved 2013-01-15.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Caton-Thompson, G.; Gardner, E. (1934). The Desert Fayum. London: Royal Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland.

- ^ Holdaway, Simon; Phillipps, Rebecca; Emmitt, Joshua; Wendrich, Willeke (2016-07-29). "The Fayum revisited: Reconsidering the role of the Neolithic package, Fayum north shore, Egypt". Quaternary International. The Neolithic from the Sahara to the Southern Mediterranean Coast: A review of the most Recent Research. 410, Part A: 173–180. doi:10.1016/j.quaint.2015.11.072.

- ^ Phillipps, Rebecca; Holdaway, Simon; Ramsay, Rebecca; Emmitt, Joshua; Wendrich, Willeke; Linseele, Veerle (2016-05-18). "Lake Level Changes, Lake Edge Basins and the Paleoenvironment of the Fayum North Shore, Egypt, during the Early to Mid-Holocene". Open Quaternary. 2 (0). doi:10.5334/oq.19. ISSN 2055-298X. Archived from the original on 2016-09-16.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help)CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Saadia Gaon, Tafsir (Judeo-Arabic translation of the Pentateuch), Exodus 1:11; Rabbi Saadia Gaon's Commentaries on the Torah (ed. Yosef Qafih), Mossad Harav Kook: Jerusalem 1984, p. 63 (Exodus 1:11) (Hebrew)

- ^ Pettigrew, Thomas (1834). A History of Egyptian Mummies: And an Account of the Worship and Embalming of the Sacred Animals by the Egyptians : with Remarks on the Funeral Ceremonies of Different Nations, and Observations on the Mummies of the Canary Islands, of the Ancient Peruvians, Burman Priests, Etc. Longman, Rees, Orme, Brown, Green, and Longman. p. 211.

- ^ Bunson, Margaret (2009). Encyclopedia of Ancient Egypt. Infobase Publishing. p. 90. ISBN 978-1-43810997-8.

- ^ Hornblower, Simon; Spawforth, Antony; Eidenow, Esther, eds. (2012). The Oxford Classical Dictionary. Oxford University Press. p. 171. ISBN 978-0-19954556-8.

- ^ Guillaume, Philippe (2008). Ptolemy the second Philadelphus and his world. Brill. p. 299. ISBN 978-90-0417089-6.

- ^ Le Quien, Michel (1740). Oriens christianus: in quatuor patriarchatus digestus : quo exhibentur ecclesiae, patriarchae caeterique praesules totius orientis. ex Typographia Regia., Vol. II, coll. 581-584

- ^ Annuario Pontificio 2013 (Libreria Editrice Vaticana 2013 ISBN 978-88-209-9070-1), p. 840

- ^ * Jalalipour, Saeid (2014). Persian Occupation of Egypt 619-629: Politics and Administration of Sasanians (PDF). Sasanika. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2015-05-26.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "History of Encaustic Art". Encaustic.ca. 2012-06-10. Archived from the original on 2012-12-23. Retrieved 2013-01-15.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Egyptology Online: Fayoum mummy portraits". Archived from the original on August 8, 2007. Retrieved January 16, 2007.

- ^ Encyclopædia Britannica Online - Egyptian art and architecture - Greco-Roman Egypt Archived 2007-05-28 at the Wayback Machine accessed on January 16, 2007

- ^ Bagnall, R.S. in Susan Walker, ed. Ancient Faces : Mummy Portraits in Roman Egypt (Metropolitan Museum of Art Publications). New York: Routledge, 2000, p. 27

- ^ Riggs, C. The Beautiful Burial in Roman Egypt: Art, Identity, and Funerary Religion Oxford University Press (2005).

- ^ Victor J. Katz (1998). A History of Mathematics: An Introduction, p. 184. Addison Wesley, ISBN 0-321-01618-1: "But what we really want to know is to what extent the Alexandrian mathematicians of the period from the first to the fifth centuries C.E. were Greek. Certainly, all of them wrote in Greek and were part of the Greek intellectual community of Alexandria. And most modern studies conclude that the Greek community coexisted [...] So should we assume that Ptolemy and Diophantus, Pappus and Hypatia were ethnically Greek, that their ancestors had come from Greece at some point in the past but had remained effectively isolated from the Egyptians? It is, of course, impossible to answer this question definitively. But research in papyri dating from the early centuries of the common era demonstrates that a significant amount of intermarriage took place between the Greek and Egyptian communities [...] And it is known that Greek marriage contracts increasingly came to resemble Egyptian ones. In addition, even from the founding of Alexandria, small numbers of Egyptians were admitted to the privileged classes in the city to fulfill numerous civic roles. Of course, it was essential in such cases for the Egyptians to become "Hellenized," to adopt Greek habits and the Greek language. Given that the Alexandrian mathematicians mentioned here were active several hundred years after the founding of the city, it would seem at least equally possible that they were ethnically Egyptian as that they remained ethnically Greek. In any case, it is unreasonable to portray them with purely European features when no physical descriptions exist."

- ^ The Mosque of Qaitbey in the Fayoum of Egypt Archived 2007-05-27 at the Wayback Machine by Seif Kamel

- ^ a b c Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 10 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 219.

- ^ "The Temple and the Gods, The Cult of the Crocodile". Umich.edu. Archived from the original on 2012-10-13. Retrieved 2013-01-15.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ a b "El Fayoum, Egypt". Voodoo Skies. Archived from the original on 24 February 2014. Retrieved 17 July 2013.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Climate: Faiyum - Climate graph, Temperature graph, Climate table". Climate-Data.org. Archived from the original on 13 December 2013. Retrieved 17 August 2013.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help)

External links

- "Photo Gallery: Water Issues in Fayoum Villages". Archived from the original on 2009-09-06.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - Falling Rain Genomics, Inc. "Geographical information on Al Fayyum, Egypt". Retrieved 2011-03-22.

- Fayum towns and their papyri, edited with translations and notes by Bernard P. Grenfell and Arthur S. Hunt at the Internet Archive

- Vincent L. Morgan; Spencer G. Lucas (2002). "Notes From Diary––Fayum Trip, 1907" (PDF). Bulletin 22. Albuquerque, New Mexico: New Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science. ISSN 1524-4156.. 148 pages, public domain.

- Fayoum Photo Gallery