Wallachia

Principality of Wallachia | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1330 – 1862 | |||||||||||||||

| Motto: Dreptate, Frăție "Justice, Brotherhood" (1848) | |||||||||||||||

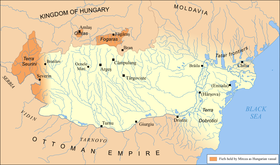

Wallachia in 1812 | |||||||||||||||

Wallachia in the late 18th century | |||||||||||||||

| Status |

| ||||||||||||||

| Capital |

| ||||||||||||||

| Common languages | |||||||||||||||

| Religion | Majority: Romanian Orthodoxy Minority: Roman Catholicism, Reformed Church, Judaism | ||||||||||||||

| Demonym(s) | Wallachian | ||||||||||||||

| Government | Elective absolute monarchy with hereditary lines | ||||||||||||||

| Prince | |||||||||||||||

• c. 1290–c. 1310 | Radu Negru (first) | ||||||||||||||

• 1859–1862 | Alexandru Ioan Cuza (last) | ||||||||||||||

| Historical era | |||||||||||||||

| 1290[9] | |||||||||||||||

| 1330 | |||||||||||||||

• Ottoman suzerainty for the first time | 1417[10] | ||||||||||||||

• Long and Moldavian Magnate wars | 1593–1621 | ||||||||||||||

| 21 July [O.S. 10 July] 1774 | |||||||||||||||

| 14 September [O.S. 2 September] 1829 | |||||||||||||||

| 1834–1835 | |||||||||||||||

| 5 February [O.S. 24 January] 1859 | |||||||||||||||

| Population | |||||||||||||||

• 1859 | 2,400,921 | ||||||||||||||

| Currency | Grosh, denarii, aspri, ducat, florin, ughi, leeuwendaalder, Austrian florin and others | ||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||

| Today part of | Romania | ||||||||||||||

Wallachia or Walachia (/wɒˈleɪkiə/;[11] Romanian: Țara Românească, lit. 'The Romanian Land' or 'The Romanian Country'; Old Romanian: Țeara Rumânească, Romanian Cyrillic alphabet: Цѣра Рꙋмѫнѣскъ) is a historical and geographical region of modern-day Romania. It is situated north of the Lower Danube and south of the Southern Carpathians. Wallachia was traditionally divided into two sections, Muntenia (Greater Wallachia) and Oltenia (Lesser Wallachia). Dobruja could sometimes be considered a third section due to its proximity and brief rule over it. Wallachia as a whole is sometimes referred to as Muntenia through identification with the larger of the two traditional sections.

Wallachia was founded as a principality in the early 14th century by Basarab I after a rebellion against Charles I of Hungary, although the first mention of the territory of Wallachia west of the river Olt dates to a charter given to the voivode Seneslau in 1246 by Béla IV of Hungary. In 1417, Wallachia was forced to accept the suzerainty of the Ottoman Empire;[10] this lasted until the 19th century.

In 1859, Wallachia united with Moldavia to form the United Principalities, which adopted the name Romania in 1866 and officially became the Kingdom of Romania in 1881. Later, following the dissolution of the Austro-Hungarian Empire and the resolution of the elected representatives of Romanians in 1918, Bukovina, Transylvania and parts of Banat, Crișana, and Maramureș were allocated to the Kingdom of Romania, thereby forming the modern Romanian state.

Etymology

[edit]The name Wallachia is an exonym, generally not used by Romanians themselves, who used the denomination "Țara Românească" – Romanian Country or Romanian Land, although it does appear in some Romanian texts as Valahia or Vlahia. It derives from the term walhaz used by Germanic peoples and Early Slavs to refer to Romans and other speakers of foreign languages. In Northwestern Europe, this gave rise to Wales, Cornwall, and Wallonia, among others, while in Southeast Europe it was used to designate Romance-speakers, and subsequently shepherds in general.

In Slavonic texts of the Early Middle Ages, the name Zemli Ungro-Vlahiskoi (Земли Унгро-Влахискои or "Hungaro-Wallachian Land") was also used as a designation for the region. The term, translated in Romanian as "Ungrovalahia", remained in use up to the modern era in a religious context, referring to the Romanian Orthodox Metropolitan seat of Hungaro-Wallachia, in contrast to Thessalian or Great Vlachia in Greece or Small Wallachia (Mala Vlaška) in Serbia.[12] The Romanian-language designations of the state were Muntenia (The Land of Mountains), Țara Rumânească (the Romanian Land), Valahia, and, rarely, România.[13] The spelling variant Țara Românească was adopted in official documents by the mid-19th century; however, the version with u remained common in local dialects until much later.[14]

For long periods after the 14th century, Wallachia was referred to as Vlashko (Bulgarian: Влашко) by Bulgarian sources, Vlaška (Serbian: Влашка) by Serbian sources, Voloschyna (Ukrainian: Волощина) by Ukrainian sources, and Walachei or Walachey by German-speaking (most notably Transylvanian Saxon) sources. The traditional Hungarian name for Wallachia is Havasalföld, literally "Snowy lowlands", the older form of which is Havaselve, meaning "Land beyond the snowy mountains" ("snowy mountains" refers to the Southern Carpathians (the Transylvanian Alps)[15][16]); its translation into Latin, Transalpina was used in the official royal documents of the Kingdom of Hungary. In Ottoman Turkish, the term Eflâk Prensliği, or simply Eflâk افلاق, appears. (Note that in a turn of linguistic luck utterly in favor of the Wallachians' eastward posterity, this toponym, at least according to the phonotactics of modern Turkish, is homophonous with another word, افلاك, meaning "heavens" or "skies".). In old Albanian, the name was "Gogënia", which was used to denote non-Albanian speakers.[17]

Arabic chronicles from the 13th century had used the name of Wallachia instead of Bulgaria. They gave the coordinates of Wallachia and specified that Wallachia was named al-Awalak and the dwellers ulaqut or ulagh.[18]

The area of Oltenia in Wallachia was also known in Turkish as Kara-Eflak ("Black Wallachia") and Kuçuk-Eflak ("Little Wallachia"),[19] while the former has also been used for Moldavia.[20]

History

[edit]| History of Romania |

|---|

|

|

|

Ancient times

[edit]In the Second Dacian War (AD 105) western Oltenia became part of the Roman province of Dacia, with parts of later Wallachia included in the Moesia Inferior province. The Roman limes was initially built along the Olt River in 119 before being moved slightly to the east in the second century, during which time it stretched from the Danube up to Rucăr in the Carpathians. The Roman line fell back to the Olt in 245 and, in 271, the Romans pulled out of the region.

The area was subject to Romanization also during the Migration Period, when most of present-day Romania was also invaded by Goths and Sarmatians known as the Chernyakhov culture, followed by waves of other nomads. In 328, the Romans built a bridge between Sucidava and Oescus (near Gigen) which indicates that there was a significant trade with the peoples north of the Danube. A short period of Roman rule in the area is attested under Emperor Constantine the Great,[21] after he attacked the Goths (who had settled north of the Danube) in 332. The period of Goth rule ended when the Huns arrived in the Pannonian Basin and, under Attila, attacked and destroyed some 170 settlements on both sides of the Danube.

Early Middle Ages

[edit]Byzantine influence is evident during the fifth to sixth century, such as the site at Ipotești–Cândești culture, but from the second half of the sixth century and in the seventh century, Slavs crossed the territory of Wallachia and settled in it, on their way to Byzantium, occupying the southern bank of the Danube.[22] In 593, the Byzantine commander-in-chief Priscus defeated Slavs, Avars and Gepids on future Wallachian territory, and, in 602, Slavs suffered a crucial defeat in the area; Flavius Mauricius Tiberius, who ordered his army to be deployed north of the Danube, encountered his troops' strong opposition.[23]

From its establishment in 681 to approximately the Hungarians' conquest of Transylvania at the end of the tenth century, the First Bulgarian Empire controlled the territory of Wallachia. With the decline and subsequent Byzantine conquest of Bulgaria (from the second half of the tenth century up to 1018), Wallachia came under the control of the Pechenegs, Turkic peoples who extended their rule west through the tenth and 11th century, until they were defeated around 1091, when the Cumans of southern Ruthenia took control of the lands of Wallachia.[24] Beginning with the tenth century, Byzantine, Bulgarian, Hungarian, and later Western sources mention the existence of small polities, possibly peopled by, among others, Vlachs led by knyazes and voivodes.

In 1241, during the Mongol invasion of Europe, Cuman domination was ended—a direct Mongol rule over Wallachia was not attested.[25] Part of Wallachia was probably briefly disputed by the Kingdom of Hungary and Bulgarians in the following period,[25] but it appears that the severe weakening of Hungarian authority during the Mongol attacks contributed to the establishment of the new and stronger polities attested in Wallachia for the following decades.[26]

Creation

[edit]

One of the first written pieces of evidence of local voivodes is in connection with Litovoi (1272), who ruled over land each side of the Carpathians (including Hațeg Country in Transylvania), and refused to pay tribute to Ladislaus IV of Hungary. His successor was his brother Bărbat (1285–1288). The continuing weakening of the Hungarian state by further Mongol invasions (1285–1319) and the fall of the Árpád dynasty opened the way for the unification of Wallachian polities, and to independence from Hungarian rule.

Wallachia's creation, held by local traditions to have been the work of one Radu Negru (Black Radu), is historically connected with Basarab I of Wallachia (1310–1352), who rebelled against Charles I of Hungary and took up rule on either side of the Olt, establishing his residence in Câmpulung as the first ruler of the House of Basarab. Basarab refused to grant Hungary the lands of Făgăraș, Almaș and the Banate of Severin, defeated Charles in the Battle of Posada (1330), and, according to Romanian historian Ștefan Ștefănescu, extended his lands to the east, to comprise lands as far as Kiliya in the Budjak (reportedly providing the origin of Bessarabia);[27] the supposed rule over the latter was not preserved by the princes that followed, as Kilia was under the rule of the Nogais c. 1334.[28]

There is evidence that the Second Bulgarian Empire ruled at least nominally the Wallachian lands up to the Rucăr–Bran corridor as late as the late 14th century. In a charter by Radu I, the Wallachian voivode requests that tsar Ivan Alexander of Bulgaria order his customs officers at Rucăr and the Dâmboviţa River bridge to collect tax following the law. The presence of Bulgarian customs officers at the Carpathians indicates a Bulgarian suzerainty over those lands, though Radu's imperative tone hints at a strong and increasing Wallachian autonomy.[29] Under Radu I and his successor Dan I, the realms in Transylvania and Severin continued to be disputed with Hungary.[30] Basarab was succeeded by Nicholas Alexander, followed by Vladislav I. Vladislav attacked Transylvania after Louis I occupied lands south of the Danube, conceded to recognize him as overlord in 1368, but rebelled again in the same year; his rule also witnessed the first confrontation between Wallachia and the Ottoman Empire (a battle in which Vladislav was allied with Ivan Shishman).[31]

1400–1600

[edit]Mircea the Elder to Radu the Great

[edit]

As the entire Balkans became an integral part of the growing Ottoman Empire (a process that concluded with the fall of Constantinople to Sultan Mehmed the Conqueror in 1453), Wallachia became engaged in frequent confrontations in the final years of the reign of Mircea I (r. 1386–1418). Mircea initially defeated the Ottomans in several battles, including the Battle of Rovine in 1394, driving them away from Dobruja and briefly extending his rule to the Danube Delta, Dobruja and Silistra (c. 1400–1404).[33] He swung between alliances with Sigismund, Holy Roman Emperor, and Jagiellon Poland (taking part in the Battle of Nicopolis),[34] and accepted a peace treaty with the Ottomans in 1417, after Mehmed I took control of Turnu Măgurele and Giurgiu.[35] The two ports remained part of the Ottoman state, with brief interruptions, until 1829. In 1418–1420, Michael I defeated the Ottomans in Severin, only to be killed in battle by the counter-offensive; in 1422, the danger was averted for a short while when Dan II inflicted a defeat on Murad II with the help of Pippo Spano.[36]

The peace signed in 1428 inaugurated a period of internal crisis, as Dan had to defend himself against Radu II, who led the first in a series of boyar coalitions against established princes.[37] Victorious in 1431 (the year when the boyar-backed Alexander I Aldea took the throne), boyars were dealt successive blows by Vlad II Dracul (1436–1442; 1443–1447), who nevertheless attempted to compromise between the Ottoman Sultan and the Holy Roman Empire.[38]

The following decade was marked by the conflict between the rival houses of Dănești and Drăculești. Faced with both internal and external conflict, Vlad II Dracul reluctantly agreed to pay the tribute demanded of him by the Ottoman Empire, despite his affiliation with the Order of the Dragon, a group of independent noblemen whose creed had been to repel the Ottoman invasion. As part of the tribute, the sons of Vlad II Dracul (Radu cel Frumos and Vlad III Dracula) were taken into Ottoman custody. Recognizing the Christian resistance to their invasion, leaders of the Ottoman Empire released Vlad III to rule in 1448 after his father's assassination in 1447.

Known as Vlad III the Impaler or Vlad III Dracula, he immediately put to death the boyars who had conspired against his father, and was characterized as both a national hero and a cruel tyrant.[39] He was cheered for restoring order to a destabilized principality, yet showed no mercy toward thieves, murderers or anyone who plotted against his rule. Vlad demonstrated his intolerance for criminals by utilizing impalement as a form of execution. Vlad fiercely resisted Ottoman rule, having both repelled the Ottomans and been pushed back several times.

The Transylvanian Saxons were also furious with him for strengthening the borders of Wallachia, which interfered with their control of trade routes. In retaliation, the Saxons distributed grotesque poems of cruelty and other propaganda, demonizing Vlad III Dracula as a drinker of blood.[40] These tales strongly influenced an eruption of vampiric fiction throughout the West and, in particular, Germany. They also inspired the main character in the 1897 Gothic novel Dracula by Bram Stoker.[41][self-published source?]

In 1462, Vlad III was defeated by Mehmed the Conqueror during his offensive at the Night Attack at Târgovişte before being forced to retreat to Târgoviște and accepting to pay an increased tribute.[42] Meanwhile, Vlad III faced parallel conflicts with his brother, Radu cel Frumos, (r. 1437/1439–1475), and Basarab Laiotă cel Bătrân. This led to the conquest of Wallachia by Radu, who would face his own struggles with the resurgent Vlad III and Basarab Laiotă cel Bătrân during his 11-year reign.[43] Subsequently, Radu IV the Great (Radu cel Mare, who ruled 1495–1508) reached several compromises with the boyars, ensuring a period of internal stability that contrasted his clash with Bogdan III the One-Eyed of Moldavia.[44]

Mihnea cel Rău to Petru Cercel

[edit]The late 15th century saw the ascension of the powerful Craiovești family, virtually independent rulers of the Oltenian banat, who sought Ottoman support in their rivalry with Mihnea cel Rău (1508–1510) and replaced him with Vlăduț. After the latter proved to be hostile to the bans, the House of Basarab formally ended with the rise of Neagoe Basarab, a Craioveşti.[45] Neagoe's peaceful rule (1512–1521) was noted for its cultural aspects (the building of the Curtea de Argeş Cathedral and Renaissance influences). It was also a period of increased influence for the Saxon merchants in Brașov and Sibiu, and of Wallachia's alliance with Louis II of Hungary.[46] Under Teodosie, the country was again under a four-month-long Ottoman occupation, a military administration that seemed to be an attempt to create a Wallachian Pashaluk.[47] This danger rallied all boyars in support of Radu de la Afumaţi (four rules between 1522 and 1529), who lost the battle after an agreement between the Craiovești and Sultan Süleyman the Magnificent; Prince Radu eventually confirmed Süleyman's position as suzerain and agreed to pay an even higher tribute.[47]

Ottoman suzerainty remained virtually unchallenged throughout the following 90 years. Radu Paisie, who was deposed by Süleyman in 1545, ceded the port of Brăila to Ottoman administration in the same year. His successor Mircea Ciobanul (1545–1554; 1558–1559), a prince without any claim to noble heritage, was imposed on the throne and consequently agreed to a decrease in autonomy (increasing taxes and carrying out an armed intervention in Transylvania – supporting the pro-Turkish John Zápolya).[48] Conflicts between boyar families became stringent after the rule of Pătrașcu the Good, and boyar ascendancy over rulers was obvious under Petru the Younger (1559–1568; a reign dominated by Doamna Chiajna and marked by huge increases in taxes), Mihnea Turcitul, and Petru Cercel.[49]

The Ottoman Empire increasingly relied on Wallachia and Moldavia for the supply and maintenance of its military forces; the local army, however, soon disappeared due to the increased costs and the much more obvious efficiency of mercenary troops.[50]

17th century

[edit]

Initially profiting from Ottoman support, Michael the Brave ascended to the throne in 1593, and attacked the troops of Murad III north and south of the Danube in an alliance with Transylvania's Sigismund Báthory and Moldavia's Aron Vodă (see Battle of Călugăreni). He soon placed himself under the suzerainty of Rudolf II, the Holy Roman Emperor, and, in 1599–1600, intervened in Transylvania against Poland's king Sigismund III Vasa, placing the region under his authority; his brief rule also extended to Moldavia later in the following year.[51] For a brief period, Michael the Brave ruled (in a personal, but not formal, union)[52] most of the territories where Romanians lived, rebuilding the base of the ancient Kingdom of Dacia.[53] The rule of Michael the Brave, with its break with Ottoman rule, tense relations with other European powers and the leadership of the three states, was considered in later periods as the precursor of a modern Romania, a thesis which was argued with noted intensity by Nicolae Bălcescu.[citation needed] Following Michael's downfall, Wallachia was occupied by the Polish–Moldavian army of Simion Movilă (see Moldavian Magnate Wars), who held the region until 1602, and was subject to Nogai attacks in the same year.[54]

The last stage in the Growth of the Ottoman Empire brought increased pressures on Wallachia: political control was accompanied by Ottoman economical hegemony, the discarding of the capital in Târgoviște in favour of Bucharest (closer to the Ottoman border, and a rapidly growing trade center), the establishment of serfdom under Michael the Brave as a measure to increase manorial revenues, and the decrease in importance of low-ranking boyars (threatened with extinction, they took part in the seimeni rebellion of 1655).[55] Furthermore, the growing importance of appointment to high office in front of land ownership brought about an influx of Greek and Levantine families, a process already resented by locals during the rules of Radu Mihnea in the early 17th century.[56] Matei Basarab, a boyar appointee, brought a long period of relative peace (1632–1654), with the noted exception of the 1653 Battle of Finta, fought between Wallachians and the troops of Moldavian prince Vasile Lupu—ending in disaster for the latter, who was replaced with Prince Matei's favourite, Gheorghe Ștefan, on the throne in Iași. A close alliance between Gheorghe Ștefan and Matei's successor Constantin Șerban was maintained by Transylvania's George II Rákóczi, but their designs for independence from Ottoman rule were crushed by the troops of Mehmed IV in 1658–1659.[57] The reigns of Gheorghe Ghica and Grigore I Ghica, the sultan's favourites, signified attempts to prevent such incidents; however, they were also the onset of a violent clash between the Băleanu and Cantacuzino boyar families, which was to mark Wallachia's history until the 1680s.[58] The Cantacuzinos, threatened by the alliance between the Băleanus and the Ghicas, backed their own choice of princes (Antonie Vodă din Popești and George Ducas)[59] before promoting themselves—with the ascension of Șerban Cantacuzino (1678–1688).

Russo-Turkish Wars and the Phanariotes

[edit]

Wallachia became a target for Habsburg incursions during the last stages of the Great Turkish War around 1690, when the ruler Constantin Brâncoveanu secretly and unsuccessfully negotiated an anti-Ottoman coalition. Brâncoveanu's reign (1688–1714), noted for its late Renaissance cultural achievements (see Brâncovenesc style), also coincided with the rise of Imperial Russia under Tsar Peter the Great—he was approached by the latter during the Russo-Turkish War of 1710–11, and lost his throne and life sometime after sultan Ahmed III caught news of the negotiations.[60] Despite his denunciation of Brâncoveanu's policies, Ștefan Cantacuzino attached himself to Habsburg projects and opened the country to the armies of Prince Eugene of Savoy; he was himself deposed and executed in 1716.[61]

Immediately following the deposition of Prince Ștefan, the Ottomans renounced the purely nominal elective system (which had by then already witnessed the decrease in importance of the Boyar Divan over the sultan's decision), and princes of the two Danubian Principalities were appointed from the Phanariotes of Constantinople. Inaugurated by Nicholas Mavrocordatos in Moldavia after Dimitrie Cantemir, Phanariote rule was brought to Wallachia in 1715 by the very same ruler.[62] The tense relations between boyars and princes brought a decrease in the number of taxed people (as a privilege gained by the former), a subsequent increase in total taxes,[63] and the enlarged powers of a boyar circle in the Divan.[64]

In parallel, Wallachia became the battleground in a succession of wars between the Ottomans on one side and Russia or the Habsburg monarchy on the other. Mavrocordatos himself was deposed by a boyar rebellion, and arrested by Habsburg troops during the Austro-Turkish War of 1716–18, as the Ottomans had to concede Oltenia to Charles VI of Austria (the Treaty of Passarowitz).[65] The region, organized as the Banat of Craiova and subject to an enlightened absolutist rule that soon disenchanted local boyars, was returned to Wallachia in 1739 (the Treaty of Belgrade, upon the close of the Austro-Russian–Turkish War (1735–39)). Prince Constantine Mavrocordatos, who oversaw the new change in borders, was also responsible for the effective abolition of serfdom in 1746 (which put a stop to the exodus of peasants into Transylvania);[66] during this period, the ban of Oltenia moved his residence from Craiova to Bucharest, signalling, alongside Mavrocordatos' order to merge his personal treasury with that of the country, a move towards centralism.[67]

In 1768, during the Fifth Russo-Turkish War, Wallachia was placed under its first Russian occupation (helped along by the rebellion of Pârvu Cantacuzino).[68] The Treaty of Küçük Kaynarca (1774) allowed Russia to intervene in favour of Eastern Orthodox Ottoman subjects, curtailing Ottoman pressures—including the decrease in sums owed as tribute[69]—and, in time, relatively increasing internal stability while opening Wallachia to more Russian interventions.[70]

Habsburg troops, under Prince Josias of Coburg, again entered the country during the Russo-Turkish-Austrian War, deposing Nicholas Mavrogenes in 1789.[71] A period of crisis followed the Ottoman recovery: Oltenia was devastated by the expeditions of Osman Pazvantoğlu, a powerful rebellious pasha whose raids even caused prince Constantine Hangerli to lose his life on suspicion of treason (1799), and Alexander Mourousis to renounce his throne (1801).[72] In 1806, the Russo-Turkish War of 1806–12 was partly instigated by the Porte's deposition of Constantine Ypsilantis in Bucharest—in tune with the Napoleonic Wars, it was instigated by the French Empire, and also showed the impact of the Treaty of Küçük Kaynarca (with its permissive attitude towards Russian political influence in the Danubian Principalities); the war brought the invasion of Mikhail Andreyevich Miloradovich.[73] After the Peace of Bucharest, the rule of Jean Georges Caradja, although remembered for a major plague epidemic, was notable for its cultural and industrial ventures.[74] During the period, Wallachia increased its strategic importance for most European states interested in supervising Russian expansion; consulates were opened in Bucharest, having an indirect but major impact on Wallachian economy through the protection they extended to Sudiți traders (who soon competed successfully against local guilds).[75]

From Wallachia to Romania

[edit]Early 19th century

[edit]The death of prince Alexander Soutzos in 1821, coinciding with the outbreak of the Greek War of Independence, established a boyar regency which attempted to block the arrival of Scarlat Callimachi to his throne in Bucharest. The parallel uprising in Oltenia, carried out by the Pandur leader Tudor Vladimirescu, although aimed at overthrowing the ascendancy of Greeks,[76] compromised with the Greek revolutionaries in the Filiki Eteria and allied itself with the regents,[77] while seeking Russian support[78] (see also: Rise of nationalism under the Ottoman Empire).

On 21 March 1821 Vladimirescu entered Bucharest. For the following weeks, relations between him and his allies worsened, especially after he sought an agreement with the Ottomans;[79] Eteria's leader Alexander Ypsilantis, who had established himself in Moldavia and, after May, in northern Wallachia, viewed the alliance as broken—he had Vladimirescu executed, and faced the Ottoman intervention without Pandur or Russian backing, suffering major defeats in Bucharest and Drăgășani (before retreating to Austrian custody in Transylvania).[80] These violent events, which had seen the majority of Phanariotes siding with Ypsilantis, made Sultan Mahmud II place the Principalities under its occupation (evicted by a request of several European powers),[81] and sanction the end of Phanariote rules: in Wallachia, the first prince to be considered a local one after 1715 was Grigore IV Ghica. Although the new system was confirmed for the rest of Wallachia's existence as a state, Ghica's rule was abruptly ended by the devastating Russo-Turkish War of 1828–1829.[82]

The 1829 Treaty of Adrianople placed Wallachia and Moldavia under Russian military rule, without overturning Ottoman suzerainty, awarding them the first common institutions and semblance of a constitution (see Regulamentul Organic). Wallachia was returned ownership of Brăila, Giurgiu (both of which soon developed into major trading cities on the Danube), and Turnu Măgurele.[83] The treaty also allowed Moldavia and Wallachia to freely trade with countries other than the Ottoman Empire, which signalled substantial economic and urban growth, as well as improving the peasant situation.[84] Many of the provisions had been specified by the 1826 Akkerman Convention between Russia and the Ottomans, but it had never been fully implemented in the three-year interval.[85] The duty of overseeing of the Principalities was left to Russian general Pavel Kiselyov; this period was marked by a series of major changes, including the reestablishment of a Wallachian Army (1831), a tax reform (which nonetheless confirmed tax exemptions for the privileged), as well as major urban works in Bucharest and other cities.[86] In 1834, Wallachia's throne was occupied by Alexandru II Ghica—a move in contradiction with the Adrianople treaty, as he had not been elected by the new Legislative Assembly; he was removed by the suzerains in 1842 and replaced with an elected prince, Gheorghe Bibescu.[87]

1840s–1850s

[edit]

Opposition to Ghica's arbitrary and highly conservative rule, together with the rise of liberal and radical currents, was first felt with the protests voiced by Ion Câmpineanu (quickly repressed);[88] subsequently, it became increasingly conspiratorial, and centered on those secret societies created by young officers such as Nicolae Bălcescu and Mitică Filipescu.[89] Frăția, a clandestine movement created in 1843, began planning a revolution to overthrow Bibescu and repeal Regulamentul Organic in 1848 (inspired by the European rebellions of the same year). Their pan-Wallachian coup d'état was initially successful only near Turnu Măgurele, where crowds cheered the Islaz Proclamation (9 June); among others, the document called for political freedoms, independence, land reform, and the creation of a national guard.[90] On 11–12 June the movement was successful in deposing Bibescu and establishing a Provisional Government,[91] which made Dreptate, Frăție ("Justice, Brotherhood") the national motto.[92] Although sympathetic to the anti-Russian goals of the revolution, the Ottomans were pressured by Russia into repressing it: Ottoman troops entered Bucharest on 13 September.[91] Russian and Turkish troops, present until 1851, brought Barbu Dimitrie Știrbei to the throne, during which interval most participants in the revolution were sent into exile.

Briefly under renewed Russian occupation during the Crimean War, Wallachia and Moldavia were given a new status with a neutral Austrian administration (1854–1856) and the Treaty of Paris: a tutelage shared by Ottomans and a Congress of Great Powers (Britain, France, the Kingdom of Piedmont-Sardinia, the Austrian Empire, Prussia, and, albeit never again fully, Russia), with a kaymakam-led internal administration. The emerging movement for a union of the Danubian Principalities (a demand first voiced in 1848, and a cause cemented by the return of revolutionary exiles) was advocated by the French and their Sardinian allies, supported by Russia and Prussia, but was rejected or suspicioned by all other overseers.[93]

After an intense campaign, a formal union was ultimately granted: nevertheless, elections for the Ad hoc Divans of 1859 profited from a legal ambiguity (the text of the final agreement specified two thrones, but did not prevent any single person from simultaneously taking part in and winning elections in both Bucharest and Iași). Alexander John Cuza, who ran for the unionist Partida Națională, won the elections in Moldavia on 5 January; Wallachia, which was expected by the unionists to carry the same vote, returned a majority of anti-unionists to its divan.[94]

Those elected changed their allegiance after a mass protest of Bucharest crowds,[94] and Cuza was voted prince of Wallachia on 5 February (24 January Old Style), consequently confirmed as Domnitor of the United Principalities of Moldavia and Wallachia (of Romania from 1862) and effectively uniting both principalities. Internationally recognized only for the duration of his reign, the union was irreversible after the ascension of Carol I in 1866 (coinciding with the Austro-Prussian War, it came at a time when Austria, the main opponent of the decision, was not in a position to intervene).

Society

[edit]

Slavery

[edit]Slavery (Romanian: robie) was part of the social order from before the founding of the Principality of Wallachia, until it was abolished in stages during the 1840s and 1850s. Most of the slaves were of Roma (Gypsy) ethnicity.[95] The very first document attesting the presence of Roma people in Wallachia dates back to 1385, and refers to the group as ațigani (from the Greek athinganoi, the origin of the Romanian term țigani, which is synonymous with "Gypsy").[96] Although the Romanian terms robie and sclavie appear to be synonyms, in terms of legal status, there are significant differences: sclavie was the term corresponding to the legal institution during the Roman era, where slaves were considered goods instead of human beings and the owners had ius vitae necisque over them (right to end the life of the slave); while robie is the feudal institution where the slaves were legally considered human beings and they had reduced legal capacity.[97]

The exact origins of slavery in Wallachia are not known. Slavery was a common practice in Eastern Europe at the time, and there is some debate over whether the Romani people came to Wallachia as free people or as slaves. In the Byzantine Empire, they were slaves of the state and it seems the situation was the same in Bulgaria and Serbia[citation needed] until their social organization was destroyed by the Ottoman conquest, which would suggest that they came as slaves who had a change of 'ownership'. Historian Nicolae Iorga associated the Roma people's arrival with the 1241 Mongol invasion of Europe and considered their slavery as a vestige of that era, the Romanians taking the Roma from the Mongols as slaves and preserving their status. Other historians consider that they were enslaved while captured during the battles with the Tatars. The practice of enslaving prisoners may also have been taken from the Mongols.[95] While it is possible that some Romani people were slaves or auxiliary troops of the Mongols or Tatars, the bulk of them came from south of the Danube at the end of the 14th century, some time after the foundation of Wallachia. The arrival of the Roma made slavery a widespread practice.[98]

Traditionally, Roma slaves were divided into three categories. The smallest was owned by the hospodars, and went by the Romanian-language name of țigani domnești ("Gypsies belonging to the lord"). The two other categories comprised țigani mănăstirești ("Gypsies belonging to the monasteries"), who were the property of Romanian Orthodox and Greek Orthodox monasteries, and țigani boierești ("Gypsies belonging to the boyars"), who were enslaved by the category of landowners.[96][99]

The abolition of slavery was carried out following a campaign by young revolutionaries who embraced the liberal ideas of the Enlightenment. The earliest law which freed a category of slaves was in March 1843, which transferred the control of the state slaves owned by the prison authority to the local authorities, leading to their sedentarizing and becoming peasants. During the Wallachian Revolution of 1848, the agenda of the Provisional Government included the emancipation (dezrobire) of the Roma as one of the main social demands. By the 1850s the movement gained support from almost the whole of Romanian society, and the law from February 1856 emancipated all slaves to the status of taxpayers (citizens).[95][96]

Wallachian insignia

[edit]Flags

[edit]-

Heraldic flag under Michael the Brave (1593-1611)[100]

-

Flag under Mihnea III (1658)[101]

-

Naval ensign under Constantin Brâncoveanu (1700)[101]

-

Princely banner of Scarlat Ghica (1758)[101]

-

Princely banner of Alexandros Soutzos (1802)[101]

-

Constantine Ypsilantis' banner (1806)[101]

-

Flag of the Wallachian uprising of 1821[101]

-

War ensign of the Principality of Wallachia (1834)

-

Flag of the Wallachian Revolution of 1848[101]

-

Naval ensign of the Principality of Wallachia (1858)[101]

Coats of arms and other insignia

[edit]-

Coat of arms under Vladislav I (1377)

-

Wallachian coins minted during the Basarab dynasty (1310-1627)

-

Seal used by Mircea the Elder (1390)[102]

-

Coat of arms under Dan II of Wallachia (1420)

-

Coat of arms under Vladislav II (1447)

-

Emblem of Wallachia under Radu Paisie (1545)[101]

-

Coat of arms under Radu Serban (1608)[101]

-

Coat of arms under Matei Basarab (1632)[101]

-

Coat of arms under Serban Cantacuzino (1688)[101]

-

Coat of arms under Constantin Brâncoveanu (1700)

-

Coat of arms under Dionisie Eclesiarhul (1795)[101]

-

Seal used by John George Caradja (1812)[102]

Military forces

[edit]Geography

[edit]

With an area of approximately 77,000 km2 (30,000 sq mi), Wallachia is situated north of the Danube (and of present-day Bulgaria), east of Serbia and south of the Southern Carpathians, and is traditionally divided between Muntenia in the east (as the political center, Muntenia is often understood as being synonymous with Wallachia), and Oltenia (a former banat) in the west. The division line between the two is the Olt River.

Wallachia's traditional border with Moldavia coincided with the Milcov River for most of its length. To the east, over the Danube north-south bend, Wallachia neighbours Dobruja (Northern Dobruja). Over the Carpathians, Wallachia shared a border with Transylvania; Wallachian princes have for long held possession of areas north of the line (Amlaș, Ciceu, Făgăraș, and Hațeg), which are generally not considered part of Wallachia proper.

The capital city changed over time, from Câmpulung to Curtea de Argeș, then to Târgoviște and, after the late 17th century, to Bucharest.

Map gallery

[edit]-

Wallachia, as shown on a wider map of the Black Sea (mid 16th century)

-

Wallachia, as part of the Holy League's Orthodox states

-

The Principalities of Moldavia and Wallachia in 1786, as depicted on an Italian map by G. Pittori (after the geographer Giovanni Antonio Rizzi Zannoni)

-

F.J.J., von Reilly, Das Furstenthum Walachey, Viena, 1789

-

Salt trade in Wallachia between the 16th and 19th centuries

-

The region of Wallachia within contemporary Romania

Population

[edit]Historical population

[edit]Contemporary historians estimate the population of Wallachia in the 15th century at 500,000 people.[103] In 1859, the population of Wallachia was 2,400,921 (1,586,596 in Muntenia and 814,325 in Oltenia).[104]

Current population

[edit]According to the latest 2011 census data, the region has a total population of 8,256,532 inhabitants, distributed among the ethnic groups as follows (as per 2001 census): Romanians (97%), Roma (2.5%), others (0.5%).[105]

Cities

[edit]The largest cities (as per the 2011 census) in the Wallachia region are:

- Bucharest (1,883,425)

- Craiova (269,506)

- Ploiești (209,945)

- Brăila (180,302)

- Pitești (155,383)

- Buzău (115,494)

- Drobeta-Turnu Severin (92,617)

- Râmnicu Vâlcea (92,573)

See also

[edit]- History of Bucharest

- List of rulers of Wallachia

- Balkan–Danubian culture

- Bulgarian lands across the Danube

Notes

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Walachia Archived 19 September 2018 at the Wayback Machine at britannica.com

- ^ a b Protectorate Archived 14 December 2020 at the Wayback Machine at britannica.com

- ^ Reid, Robert; Pettersen, Leif (11 November 2017). Romania & Moldova. Lonely Planet. ISBN 9781741044782. Archived from the original on 16 July 2023. Retrieved 11 November 2017 – via Google Books.

- ^ Ștefan Pascu, Documente străine despre români, ed. Arhivelor statului, București 1992, ISBN 973-95711-2-3

- ^ "Tout ce pays: la Wallachie, la Moldavie et la plus part de la Transylvanie, a esté peuplé des colonies romaines du temps de Trajan l'empereur... Ceux du pays se disent vrais successeurs des Romains et nomment leur parler romanechte, c'est-à-dire romain... " in Voyage fait par moy, Pierre Lescalopier l'an 1574 de Venise a Constantinople, in: Paul Cernovodeanu, Studii și materiale de istorie medievală, IV, 1960, p. 444

- ^ Panaitescu, Petre P. (1965). Începuturile şi biruinţa scrisului în limba română (in Romanian). Editura Academiei Bucureşti. p. 5.

- ^ Kamusella, T. (2008). The Politics of Language and Nationalism in Modern Central Europe. Springer. p. 352. ISBN 9780230583474. Archived from the original on 16 July 2023. Retrieved 29 November 2018.

- ^ Olson, James Stuart; Pappas, Lee Brigance; Pappas, Nicholas Charles; Pappas, Nicholas C. J. (1994). An Ethnohistorical Dictionary of the Russian and Soviet Empires. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 550. ISBN 9780313274978. Archived from the original on 16 July 2023. Retrieved 29 November 2018.

- ^ Brătianu 1980, p. 93.

- ^ a b Giurescu, Istoria Românilor, p. 481

- ^ "Wallachia". Dictionary.com Unabridged (Online). n.d. Retrieved 6 November 2021.

- ^ Dinu C. Giurescu, "Istoria ilustrată a românilor", Editura Sport-Turism, Bucharest, 1981, p. 236

- ^ "Ioan-Aurel Pop, Istoria și semnificația numelor de român/valah și România/Valahia, reception speech at the Romanian Academy, delivered on 29 Mai 2013 in public session, Bucharest, 2013, pp. 18–21". Archived from the original on 18 October 2018. Retrieved 23 July 2019. See also I.-A. Pop, "Kleine Geschichte der Ethnonyme Rumäne (Rumänien) und Walache (Walachei)," I-II, Transylvanian Review, vol. XIII, no. 2 (Summer 2014): 68–86 and no. 3 (Autumn 2014): 81–87.

- ^ Arvinte, Vasile (1983). Român, românesc, România. București: Editura Științifică și Enciclopedică. p. 52.

- ^ A multikulturális Erdély középkori gyökerei – Tiszatáj 55. évfolyam, 11. szám. 2001. november, Kristó Gyula – The medieval roots of the multicultural Transylvania – Tiszatáj 55. year. 11th issue November 2001, Gyula Kristó

- ^ "Havasalföld és Moldva megalapítása és megszervezése". Romansagtortenet.hupont.hu. Archived from the original on 30 November 2017. Retrieved 11 November 2017.

- ^ Mann, S. (1957). An English-Albanian Dictionary. University Press. p. 129

- ^ Dimitri Korobeinikov, A broken mirror: the Kipchak world in the thirteenth century. In the volume: The other Europe from the Middle Ages, Edited by Florin Curta, Brill 2008, p. 394

- ^ Frederick F. Anscombe (2006). The Ottoman Balkans, 1750–1830. Markus Wiener Publishers. ISBN 978-1-55876-383-8. Archived from the original on 16 July 2023. Retrieved 8 April 2018.

- ^ Johann Filstich (1979). Tentamen historiae Vallachicae. Editura Științifică și Enciclopedică. p. 39. Archived from the original on 16 July 2023. Retrieved 8 April 2018.

- ^ Giurescu, p. 37; Ștefănescu, p. 155

- ^ Giurescu, p. 38

- ^ Warren Treadgold, A Concise History of Byzantium, New York, St Martin's Press, 2001

- ^ Giurescu, pp. 39–40

- ^ a b Giurescu, p. 39

- ^ Ștefănescu, p. 111

- ^ Ștefănescu, p. 114

- ^ Ștefănescu, p. 119

- ^ Павлов, Пламен. "За северната граница на Второто българско царство през XIII–XIV в." (in Bulgarian). LiterNet. Archived from the original on 31 January 2020. Retrieved 8 October 2009.

- ^ Ștefănescu, p. 94

- ^ Ștefănescu, pp. 93–94

- ^ Petre Dan, Hotarele românismului în date, Editura, Litera International, Bucharest, 2005, pp. 32, 34. ISBN 973-675-278-X

- ^ Ștefănescu, p. 139

- ^ Ștefănescu, p. 97

- ^ Giurescu, Istoria Românilor, p. 479

- ^ Ștefănescu, p. 105

- ^ Ștefănescu, pp. 105–106

- ^ Ștefănescu, p. 106

- ^ Cazacu 2017, pp. 199–202.

- ^ Gerhild Scholz Williams; William Layher (eds.). Consuming News: Newspapers and Print Culture in Early Modern Europe (1500–1800). pp. 14–34. Archived from the original on 8 March 2021. Retrieved 23 July 2019.

- ^ Simone Berni (2016). Dracula by Bram Stoker: The Mystery of The Early Editions. Lulu.com. p. 57. ISBN 978-1-326-62179-7.[self-published source]

- ^ Ștefănescu, pp. 115–118

- ^ Ștefănescu, pp. 117–118, 125

- ^ Ștefănescu, p. 146

- ^ Ștefănescu, pp. 140–141

- ^ Ștefănescu, pp. 141–144

- ^ a b Ștefănescu, pp. 144–145

- ^ Ștefănescu, p. 162

- ^ Ștefănescu, pp. 163–164

- ^ Berza; Djuvara, pp. 24–26

- ^ Ștefănescu, pp. 169–180

- ^ "Cãlin Goina : How the State Shaped the Nation : an Essay on the Making of the Romanian Nation" (PDF). Epa.oszk.hu. Archived (PDF) from the original on 16 January 2007. Retrieved 11 November 2017.

- ^ Rezachevici, Constantin, Mihai Viteazul et la "Dacie" de Sigismund Báthory en 1595, Ed. Argessis, 2003, 12, pp. 155–164

- ^ Giurescu, pp. 65, 68

- ^ Giurescu, pp. 68–69, 73–75

- ^ Giurescu, pp. 68–69, 78, 268

- ^ Giurescu, p. 74

- ^ Giurescu, p. 78

- ^ Giurescu, pp. 78–79

- ^ Djuvara, pp. 31, 157, 336

- ^ Djuvara, pp. 31, 336

- ^ Djuvara, pp. 31–32

- ^ Djuvara, pp. 67–70

- ^ Djuvara, p. 124

- ^ Djuvara, pp. 48, 92; Giurescu, pp. 94–96

- ^ Djuvara, pp. 48, 68, 91–92, 227–228, 254–256; Giurescu, p. 93

- ^ Djuvara, pp. 59, 71; Giurescu, p. 93

- ^ Djuvara, p. 285; Giurescu, pp. 98–99

- ^ Berza

- ^ Djuvara, p. 76

- ^ Giurescu, pp. 105–106

- ^ Djuvara, pp. 17–19, 282; Giurescu, p. 107

- ^ Djuvara, pp. 284–286; Giurescu, pp. 107–109

- ^ Djuvara, pp. 165, 168–169; Giurescu, p. 252

- ^ Djuvara, pp. 184–187; Giurescu, pp. 114, 115, 288

- ^ Djuvara, pp. 89, 299

- ^ Djuvara, p. 297

- ^ Giurescu, p. 115

- ^ Djuvara, p. 298

- ^ Djuvara, p. 301; Giurescu, pp. 116–117

- ^ Djuvara, p. 307

- ^ Djuvara, p. 321

- ^ Giurescu, pp. 122, 127

- ^ Djuvara, pp. 262, 324; Giurescu, pp. 127, 266

- ^ Djuvara, p. 323

- ^ Djuvara, pp. 323–324; Giurescu, pp. 122–127

- ^ Djuvara, p. 325

- ^ Djuvara, p. 329; Giurescu, p. 134

- ^ Djuvara, p. 330; Giurescu, pp. 132–133

- ^ Djuvara, p. 331; Giurescu, pp. 133–134

- ^ a b Djuvara, p. 331; Giurescu, pp. 136–137

- ^ "Decretul No. 1 al Guvernului provisoriu al Țării-Românesci". Archived from the original on 1 March 2020. Retrieved 27 March 2021.

- ^ Giurescu, pp. 139–141

- ^ a b Giurescu, p. 142

- ^ a b c Viorel Achim, The Roma in Romanian History, Central European University Press, Budapest, 2004, ISBN 963-9241-84-9

- ^ a b c Neagu Djuvara, Între Orient și Occident. Țările române la începutul epocii moderne, Humanitas, Bucharest, 1995. ISBN 973-28-0523-4 (in Romanian)

- ^ Curpăn, Vasile-Sorin (2014). Istoria dreptului românesc [History of the Romanian law] (PDF) (in Romanian). Iaşi: StudIS. pp. 61–62. ISBN 978-606-624-568-5. Archived (PDF) from the original on 3 April 2016.

- ^ Ștefan Ștefănescu, Istoria medie a României, Vol. I, Editura Universității din București, Bucharest, 1991 (in Romanian)

- ^ Will Guy, Between Past and Future: The Roma of Central and Eastern Europe, University of Hertfordshire Press, Hatfield, 2001. ISBN 1-902806-07-7

- ^ (in Romanian) Ioan Silviu Nistor, "Tricolorul românesc: simbol configurat de Mihai Viteazul", in Dacoromania, nr. 76/2015

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n (in Romanian) Maria Dogaru, "Din Heraldica României. Album", Ed. Jif, Braşov, 1994.

- ^ a b (in Romanian) Maria Dogaru, Sigiliile cancelariei domnești a Țării Românești între anii 1715-1821, în Revista Arhivelor, an 47, nr. 1, București, 1970 pp 385–421, 51 ilustrații.

- ^ East Central Europe in the Middle Ages, 1000–1500, Jean W. Sedlar, p. 255, 1994

- ^ "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 23 February 2021. Retrieved 17 January 2012.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ "Institutul Național de Statistică". Recensamant.ro. Archived from the original on 25 March 2008. Retrieved 11 November 2017.

Bibliography

[edit]- Berza, Mihai. "Haraciul Moldovei și al Țării Românești în sec. XV–XIX", in Studii și Materiale de Istorie Medie, II, 1957, pp. 7–47.

- Brătianu, Gheorghe I (1980). Tradiția istorică despre întemeierea statelor românești (The Historical Tradition of the Foundation of the Romanian States). Editura Eminescu.

- Cazacu, Matei (2017). Reinert, Stephen W. (ed.). Dracula. East Central and Eastern Europe in the Middle Ages, 450–1450. Vol. 46. Translated by Brinton, Alice; Healey, Catherine; Mordarski, Nicole; Reinert, Stephen W. Leiden: Brill Publishers. doi:10.1163/9789004349216. ISBN 978-90-04-34921-6.

- Djuvara, Neagu. Între Orient și Occident. Țările române la începutul epocii moderne, Humanitas, Bucharest, 1995.

- Giurescu, Constantin. Istoria Românilor, Vol. I, 5th edition, Bucharest, 1946.

- Giurescu, Constantin. Istoria Bucureștilor. Din cele mai vechi timpuri pînă în zilele noastre, ed. Pentru Literatură, Bucharest, 1966.

- Ștefănescu, Ștefan. Istoria medie a României, Vol. I, Bucharest, 1991.

External links

[edit]![]() Media related to Wallachia at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Wallachia at Wikimedia Commons

![Heraldic flag under Michael the Brave (1593-1611)[100]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/c/c2/Flag_of_Wallachia.svg/120px-Flag_of_Wallachia.svg.png)

![Flag under Mihnea III (1658)[101]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/0/08/SteagMihneaIII.jpg/120px-SteagMihneaIII.jpg)

![Naval ensign under Constantin Brâncoveanu (1700)[101]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/7/75/Naval_Ensign_of_Wallachia.svg/120px-Naval_Ensign_of_Wallachia.svg.png)

![Princely banner of Scarlat Ghica (1758)[101]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/f/f4/Banner_of_Scarlat_Ghica_as_Prince_of_Wallachia%2C_1758.svg/120px-Banner_of_Scarlat_Ghica_as_Prince_of_Wallachia%2C_1758.svg.png)

![Princely banner of Alexandros Soutzos (1802)[101]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/1/16/Banner_of_Alexander_Soutzos_as_Prince_of_Wallachia.svg/114px-Banner_of_Alexander_Soutzos_as_Prince_of_Wallachia.svg.png)

![Constantine Ypsilantis' banner (1806)[101]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/7/79/Constantine_Ypsilantis%27_banner.svg/120px-Constantine_Ypsilantis%27_banner.svg.png)

![Flag of the Wallachian uprising of 1821[101]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/0/06/Flag_of_Tudor_Vladimirescu%27s_Revolution_%281821%29.png/120px-Flag_of_Tudor_Vladimirescu%27s_Revolution_%281821%29.png)

![Flag of the Wallachian Revolution of 1848[101]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/8/8e/Flag_of_Wallachian_Revolution_of_1848%2C_horizontal_stripes.svg/120px-Flag_of_Wallachian_Revolution_of_1848%2C_horizontal_stripes.svg.png)

![Naval ensign of the Principality of Wallachia (1858)[101]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/68/Flagge_von_Walachischen_1858.svg/120px-Flagge_von_Walachischen_1858.svg.png)

![Coat of arms under Basarab I (1360)[101]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/9/9c/Coa_Romania_Country_Wallachia_History_2_%2814th_century%29.svg/104px-Coa_Romania_Country_Wallachia_History_2_%2814th_century%29.svg.png)

![Seal used by Mircea the Elder (1390)[102]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/0/0b/MirceaCelBatranSeal1390.png/115px-MirceaCelBatranSeal1390.png)

![Emblem of Wallachia under Radu Paisie (1545)[101]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/f/ff/Emblem_of_Wallachia_under_Radu_Paisie_%28Dimitrije_Ljubavi%C4%87%27s_Molitvenik%2C_Jan_10%2C_1545%29.png/118px-Emblem_of_Wallachia_under_Radu_Paisie_%28Dimitrije_Ljubavi%C4%87%27s_Molitvenik%2C_Jan_10%2C_1545%29.png)

![Coat of arms under Radu Serban (1608)[101]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/9/9f/RaduSerban1608blue.png/114px-RaduSerban1608blue.png)

![Coat of arms under Matei Basarab (1632)[101]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/f/f8/Coat_of_arms_of_Wallachia_under_Matei_Basarab_%28Marcus_Boschinius_version%29.svg/85px-Coat_of_arms_of_Wallachia_under_Matei_Basarab_%28Marcus_Boschinius_version%29.svg.png)

![Coat of arms under Serban Cantacuzino (1688)[101]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/2/25/SerbanCantacuzinoCoA1688.png/99px-SerbanCantacuzinoCoA1688.png)

![Coat of arms under Dionisie Eclesiarhul (1795)[101]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/b/b8/Dionisie_Eclesiarhul_-_Coat_of_arms_of_Wallachia%2C_1795.png/114px-Dionisie_Eclesiarhul_-_Coat_of_arms_of_Wallachia%2C_1795.png)

![Seal used by John George Caradja (1812)[102]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/1/18/John_George_Caradja%27s_seal%2C_1818.png/110px-John_George_Caradja%27s_seal%2C_1818.png)