History of Prayagraj

Allahabad (Hindi: इलाहाबाद), also known by its original name Prayag (Hindi: प्रयाग), is one of the largest cities of the North Indian state of Uttar Pradesh in India. Although Prayaga was renamed Ilahabad in 1575, the name later became Allahabad in an anglicized version in Roman script. The city is situated on an inland peninsula, surrounded by the rivers Ganges and Yamuna on three sides, with only one side connected to the mainland Doab region, of which it is a part. This position is of importance in Hindu scriptures for it is situated at the confluence, known as Triveni Sangam, of the holy rivers. As per Rigveda the Sarasvati River (now dried up) was part of the three river confluence in ancient times. It is one of four sites of the Kumbh Mela, an important mass Hindu pilgrimage.

The ancient name of the city is Prayag (Sanskrit for "place of sacrifice"), as it is believed to be the spot where Brahma offered his first sacrifice after creating the world. Since its founding, Prayaga renamed Allahabad has played an important role in the history and cultural life of India.

History

Ancient times

The city was originally known as Prayaga (place of the confluences) – a name that is still often used. Excavations have revealed Iron Age Northern Black Polished Ware in present-day Allahabad. That it is an ancient town is also illustrated by references in the Vedas (the most ancient of Hindu sacred texts) to Prayaga. It is believed to be the location where Brahma, the Creator of the Universe, attended a sacrificial ritual.

The Puranas, another important group of religious texts, record that Yayati left Prayaga and conquered the region of Sapta Sindhu.[1] His five sons Yadu, Druhyu, Puru, Anu and Turvashas became the main tribes of the Rigveda.

When the Aryans first settled in the North Western part of India, Prayag was part of their territory, (of the Kuru tribe), although, it was not settled and most of Doab consisted of dense forests at that time.

The centre of action at that time was in the Punjab, where the Vedas were written. Rig Veda, written during that period has a special mention of Prayag as a holy place. The Kurus) ruled the Doab and Kurukshetra area from Hastinapur (near present-day Delhi). In the Later Vedic period, when Hastinapur was destroyed by floods, the Kuru King Nichakshu transferred his entire capital with its citizens to a place next to Prayaga, which he named as Kaushambi (near present-day Allahabad).

As the centre of activity shifted from the Punjab to the Doab, termed as Aryavarta, in the post Vedic period, the importance of both Kaushambi and Prayaga rose significantly. Indeed, Prayaga became the centre of the post Vedic culture and the emergence of modern Hinduism, as we know it today. In the coming centuries, Kaushambi also became an important seat of Buddhism.

The Kurus were later divided into the Kurus and Vatsas. With Kurus controlling the Upper Doab and Kurukshetra area, while the Vatsas controlling the middle and lower Doab. Later the Vatsas too were divided into two groups, with one group ruling from Mathura, and the other group ruling from Kaushambi.

During the Ramayana epic era, Prayaga was made up of a few rishi's huts at the confluence of the sacred rivers, and much of the countryside was continuous jungle. Lord Rama, the main protagonist in the Ramayana, spent some time here, at the Ashram of Sage Bharadwaj, before proceeding to nearby Chitrakoot.

The Doab region, including Prayaga, was controlled by several empires and dynasties in the ages to come. It became a part of the Mauryan and Gupta empires of the east and the Kushan empire of the west before becoming part of the Kannauj empire. Objects unearthed in Prayaga (now Allahabad) indicate that it was part of the Kushana empire in the 1st century AD. According to Rajtarangini of Kalhana, in 780 CE, Prayag was also an important part of the kingdom of Karkota king of Kashmir, Jayapida. [2] Jayapida constructed a monument at Prayag, which existed at Kalhana's time.

In his memoirs on India, Huien Tsang, the Chinese Buddhist monk and chronicler who travelled through India during Harshavardhana's reign (A.D. 607–647), writes that he visited Prayaga in A.D. 643.

Turkic rule

Prayaga became a part of the Delhi Sultanate when the town was annexed by Muhammad of Ghor in 1193.

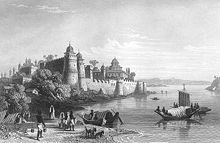

The Mughal invasion of India began in 1526, and Prayaga then became a part of their empire. Understanding the strategic position of the place in the Doab region, at the confluence of its defining rivers which had immense navigational potential, the Mughal emperor Akbar built a magnificent fort – one of his largest – on the banks of the holy Sangam and re-christened the town as Illahabad in 1575. The fort has an Ashokan pillar and some temples, and was largely a military barracks.

It was from Allahabad that Prince Salim led a revolt against his father Akbar. In 1602, prince Salim held a parallel imperial court in Akbar's fort here, ignoring the royal summons to leave Allahabad and proceed to Agra. However, before his death in 1605, Akbar named Salim his successor. Salim later served as emperor under the name Jahangir.

Maratha rule

Before British rule was imposed over Allahabad, the city was conquered by Maratha Empire. Marathas left behind two beautiful eighteenth-century temples with intricate architecture.

British rule

In 1765, the combined forces of the Nawab of Awadh and the Mughal emperor Shah Alam II lost the Battle of Buxar to the British. Although the British did not take over their states at that time, they established a garrison at Fort Allahabad, understanding its strategic position as the gateway to the northwest. Governor General Warren Hastings later took Allahabad from Shah Alam and gave it to Awadh, alleging that he had placed himself in the power of the Marathas.

In 1801 the Nawab of Awadh ceded the city to the British East India Company. Gradually the other parts of Doab and adjoining regions to its west (including the Delhi and Ajmer-Merwara regions) were won by the British. These northwestern areas were made into a new province called the North-Western Provinces, with its capital at Agra. Allahabad was located in this province.[3]

In 1834, Allahabad became the seat of the Government of Agra Province and a High Court was established. A year later both were relocated to Agra.

In 1857, Allahabad was active in the Indian Mutiny. After the mutiny, the British truncated the Delhi region of the state, merging it with Punjab, and transferred the capital of the North-Western Provinces to Allahabad, where it remained for the next twenty years.

In 1877 the two provinces of Agra and Awadh were merged to form a new state which was called the United Provinces of Agra and Oudh. Allahabad was the capital of this new state till the 1920s.

Allahabad, the freedom struggle, and Indian politics

During the Mutiny of 1857, Allahabad had only a small garrison of European troops. Taking advantage of this, the rebels brought Allahabad under their control. Maulvi Liaquat Ali, one of the prominent leaders of the rebellion, was a native of the village of Mahgaon near Allahabad.

After the Mutiny was quelled, the British established the High Court, the Police Headquarters and the Public Service Commission in the city. This transformed Allahabad into an administrative center, a status that it enjoys to this day.

The fourth and eighth session of the Indian National Congress was held in the city in 1888 and 1892 respectively on the extensive grounds of Darbhanga Castle, Allahabad.[4][5] At the turn of the century, Allahabad also became a nodal point for the revolutionaries.

In 1931, at Alfred Park in Allahabad, the revolutionary Chandrashekhar Azad killed himself when surrounded by the British Police. The Nehru family homes of Anand Bhavan and Swaraj Bhavan, both in Allahabad, were at the center of the political activities of the Indian National Congress. In the years of the struggle for Indian independence, thousands of satyagrahis (nonviolent resistors), led by Purshottam Das Tandon, Bishambhar Nath Pande and Narayan Dutt Tiwari, went to jail. The first Prime Minister of India, Jawaharlal Nehru, as well as several Union ministers such as Mangla Prasad, Muzaffar Hasan, K. N. Katju, and Lal Bahadur Shastri, were natives of Allahabad.

The first seeds of the idea of Pakistan were sown in Allahabad. On 29 December 1930, Allama Muhammad Iqbal's presidential address to the All-India Muslim League proposed a separate Muslim state for the Muslim majority regions of India.

After independence, areas from the adjoining region of Bagelkhand in the east were merged with Allahabad district, which remain part of the district to this day. The Mayawati government split the original Allahabad district into two districts, Kaushambi and Allahabad district.

Historical and archaeological sites

Allahabad has many sites of interest to tourists and archaeologists. Forty-eight kilometres to the southwest, on the banks of the Yamuna River, are the ruins of Kaushambi, which was the capital of the Vatsa kingdom and a thriving center of Buddhism. On the eastern side, across the river Ganges and connected to the city by the Shastri Bridge is Pratisthan Pur, capital of the Chandra dynasty. About 58 kilometres northwest is the medieval site of Kara with its impressive wreckage of Jaichand of Kannauj's fort. Shringaverpur, another ancient site discovered relatively recently, has become a major attraction for tourists and antiquarians alike. On the southwestern extremity of Allahabad lies Khusrobagh; it has three mausoleums, including that of Jahangir's first wife, Shah Begum.

Allahabad is the birthplace of Jawaharlal Nehru, and the Nehru family estate, called Anand Bhavan, is now a museum. It is also the birthplace of Indira Gandhi, and the home of Lal Bahadur Shastri, both later Prime Ministers of India. Vishwanath Pratap Singh and Chandra Shekhar were also associated with Allahabad. Thus, Allahabad has the distinction of being the home of several Prime Ministers in India's post-independence history.

An ancient seat of learning

Prayaga was a well-known centre of education (dating from the time of the Buddha), and into modern times. Allahabad University was founded on 23 September 1887, making it the fourth oldest university in India. It has been granted Central University status. Allahabad University is a major literary centre for Hindi studies. Many Bihari, Bengali and Gujarati scholars spent their lives here, propagated their works in Hindi and enriched the literature. In the 19th century, Allahabad University earned the epithet of 'Oxford of the East'. The founder of the International Society for Krishna Consciousness A. C. Bhaktivedanta Swami Prabhupada attained sainthood in this place.

Literary past

Many famous writers of Hindi and Urdu literature have a connection with the city. Notable amongst them are Munshi Premchand, Mahadevi Varma, Sumitranandan Pant, Suryakant Tripathi 'Nirala', Subhadra Kumari Chauhan, Upendra Nath 'Ashk' and Harivansh Rai Bachchan. This is the literary Hindi heartland. The culture of Allahabad is based on Hindi literature. Maithili Sharan Gupt was also associated with this literary Hindi soil in many ways.

The famous English author and Nobel Laureate (1907) Rudyard Kipling spent time at Allahabad working for The Pioneer as an assistant editor and overseas correspondent.

Another landmark of the literary past of Allahabad was the publishing firm Kitabistan, owned by the Rehman brothers, Kaleemur Rehman and Obaidur Rehman. They published thousands of books, including those by Nehru. They became the first publishers from India to open a branch in London in 1936.

Sanskrit scholars like Ganganath Jha, Dr. Baburam Saxena, Pandit Raghuvar Mitthulal Shastri, Professor Suresh Chandra Srivastava, and Dr. Manjushree Srivastava were both students and teachers at the University of Allahabad. The most prominent Arabic and Persian scholars included Dr. Abdul Sattar Siddiqui and his colleague Muhammad Naeemur Rehman who was known for his well organized personal library of tens of thousands of books, which was open to all.

A noteworthy poet is Raghupati Sahay, better known under the name of Firaq Gorakhpuri. Firaq was a major Urdu poet and literary critic of the 20th century. Both Firaq and Harivansh Bachchan were professors of English at Allahabad University. Firaq Gorakhpuri and Mahadevi Varma were awarded the Jnanpith Award, the highest literary honour conferred in the Republic of India in 1969 and 1982 respectively. Akbar Allahabadi is one of the most well-read poets of modern Urdu Literature. Other poets from Allahabad include Nooh Narwi, Tegh Allahabadi, Raaz Allahabadi, Firaq Gorakhpuri, and Asghar Gondvi. Professor A. K. Mehrotra, former head of English department at the University of Allahabad, has been nominated for the post of professor of poetry which was earlier held by poets like Matthew Arnold and W. H. Auden.

Short story writers Azam Kuraivi, Ibn-e-Safi, and Adil Rasheed are all from Allahabad. Critics like Dr. Aijaz Husain, Dr. Aqeel Rizwi and Hakeem Asrar Kuraivi also hail from Allahabad. Shamsur Rahman Faruqi, who edits Shabkhoon, is known all over the Urdu world as a pioneer in Post Modernist literature. Rajendra Yadav, Mamta and Ravindra Kalia, Kamaleshwar, Namwar Singh, Doodhnath Singh and many other new age literary writers and critics began their literary careers in Allahabad. The city is also home to many young and upcoming literary figures. It has also been one of the biggest centres of publication of Hindi literature; examples are Lok Bharti, Rajkamal and Neelabh.

Dr. Rajesh Verma is working on a book about eco-feminism, which will be the first major work on environment-related issues to be published in Allahabad. Allahabad has also produced a great lyricist, Virag Mishra, who recently won the Stardust Award for Standout Performance by a lyricist, for "Zinda Hoon Main".

See also

Bibliography

- Imperial Gazetteer of India, by William Wilson Hunter, James Sutherland Cotton, Sir Richard Burn, William Stevenson Meyer, Great Britain India Office, John George Bartholomew. Published by Clarendon Press, 1908.

- A Hand-book for Visitors to Lucknow: With Preliminary Notes on Allahabad and Cawnpore, by Henry George Keene. Published by Asian Educational Services, 2000 (original 1875). ISBN 81-206-1527-1.

- Allahabad: A Study in Urban Geography, by Ujagir Singh. Published by Banaras Hindu University, 1966.

- Employment and Migration in Allahabad City, by Maheshchand, Mahesh Chand, India Planning Commission. Research Programmes Committee. Published by Oxford & IBH Pub. Co., 1969.

- Subah of Allahabad Under the Great Mughals, 1580–1707: 1580–1707, by Surendra Nath Sinha. Published by Jamia Millia Islamia, 1974.

- A political history of the imperial Guptas, by Tej Ram Sharma

- The Local Roots of Indian Politics: Allahabad, 1880–1920, by Christopher Alan Bayly. Published by Clarendon Press, 1975.

- Triveni: Essays on the Cultural Heritage of Allahabad, by D. P. Dubey, Neelam Singh, Society of Pilgrimage Studies. Published by Society of Pilgrimage Studies, 1996. ISBN 81-900520-2-0.

- Magha Inscriptions in the Allahabad Museum, by Siddheshwari Narain Roy. Published by Raka Prakashana for the Museum, 1999.

- The Last Bungalow: Writings on Allahabad, by Arvind Krishna Mehrotra. Published by Penguin Books, 2007. ISBN 0-14-310118-8.

- Allahabad www.1911encyclopedia.org

- Allahabad The Imperial Gazetteer of India, 1909, v. 5, p. 226–242.

References

This article includes a list of general references, but it lacks sufficient corresponding inline citations. (October 2009) |

- ^ Talageri 1993, 2000; Elst 1999

- ^ Culture and Political History of Kashmir, Volume 1 By P. N. K. Bamzai

- ^ North Western Provinces

- ^ The Congress – First Twenty Years; Page 38 and 39

- ^ How India Wrought for Freedom: The story of the National Congress Told from the Official records (1915) by Anne Besant.