History of the tank

This article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these messages)

|

The history of the tank began in World War I, when armoured all-terrain fighting vehicles were first deployed as a response to the problems of trench warfare, ushering in a new era of mechanized warfare. Though initially crude and unreliable, tanks eventually became a mainstay of ground armies. By World War II, tank design had advanced significantly, and tanks were used in quantity in all land theatres of the war. The Cold War saw the rise of modern tank doctrine and the rise of the general-purpose main battle tank. The tank still provides the backbone to land combat operations in the 21st century.

Development

World War I generated new demands for armoured self-propelled weapons which could navigate any kind of terrain, and this led to the development of the tank. The great weakness of the tank's predecessor, the armoured car, was that it required smooth terrain to move upon, and new developments were needed for cross-country capability.[1]: 35

The tank was originally designed as a special weapon to solve an unusual tactical situation: the stalemate of the trenches on the Western Front. "It was a weapon designed for one simple task: crossing the killing zone between trench lines and breaking into enemy (defences)."[2] The armoured tank was intended to be able to protect against bullets and shell splinters, and pass through barbed wire in a way infantry units could not hope to, thus allowing the stalemate to be broken.

Few recognised during World War I that the means for returning mobility and shock action to combat was already present in a device destined to revolutionise warfare on the ground and in the air. This was the internal combustion engine, which had made possible the development of the tank and eventually would lead to the mechanised forces that were to assume the old roles of horse cavalry and to loosen the grip of the machine-gun on the battlefield. With increased firepower and protection, these mechanised forces would, only some 20 years later, become the armour of World War II. When self-propelled artillery, the armoured personnel carrier, the wheeled cargo vehicle, and supporting aviation — all with adequate communications — were combined to constitute the modern armoured division, commanders regained the capability of manoeuvre.

Numerous concepts of armoured all-terrain vehicles had been imagined for a long time. With advent of trench warfare in World War I, the Allied French and British developments of the tank were largely parallel and coincided in time.[3]

Early concepts

In the 15th century, a Hussite called Jan Žižka won several battles using armoured wagons containing cannon that could be fired through holes in their sides. But his invention was not used after his lifetime until the 20th century.[4]

In 1903, a French artillery captain named Levavasseur proposed the Levavasseur project, a canon autopropulseur (self-propelled cannon), moved by a caterpillar system and fully armoured for protection.[5]: 65 [6]: 99–100 Powered by an 80 hp petrol engine, "the Levavasseur machine would have had a crew of three, storage for ammunition, and a cross-country ability",[7]: 65 but the viability of the project was disputed by the Artillery Technical Committee, until it was formally abandoned in 1908 when it was known that a caterpillar tractor had been developed, the Hornsby of engineer David Roberts.[6]: 99–100

H. G. Wells, in his short story The Land Ironclads, published in The Strand Magazine in December 1903, had described the use of large, armed, armoured cross-country vehicles equipped with pedrail wheels (an invention which he acknowledged as the source for his inspiration),[8] to break through a system of fortified trenches, disrupting the defence and clearing the way for an infantry advance:

"They were essentially long, narrow and very strong steel frameworks carrying the engines, and borne upon eight pairs of big pedrail wheels, each about ten feet in diameter, each a driving wheel and set upon long axles free to swivel round a common axis. This arrangement gave them the maximum of adaptability to the contours of the ground. They crawled level along the ground with one foot high upon a hillock and another deep in a depression, and they could hold themselves erect and steady sideways upon even a steep hillside."[9]

In the years before the Great War, two practical tank-like designs were proposed but not developed. In 1911, the Austrian engineering officer Günther Burstyn submitted a proposal for a fighting vehicle that had a gun in a rotating turret. In 1912, the Australian civil engineer Lancelot de Mole's proposal included a scale model of a functional fully tracked vehicle. Both of these were rejected by their respective governmental administrations.

American tracked tractors in Europe

Benjamin Holt of the Holt Manufacturing Company of Stockton, California was the first to file a US patent for a workable crawler type tractor in 1907.[10] The centre of such innovation was in England, and in 1903 he travelled to England to learn more about ongoing development, though all those he saw failed their field tests.[11] Holt paid Alvin Lombard US$60,000 (equivalent to $2,034,667 in 2023) for the right to produce vehicles under Lombard's patent for the Lombard Steam Log Hauler.[12]

Holt returned to Stockton and, utilising his knowledge and his company's metallurgical capabilities, he became the first to design and manufacture practical continuous tracks for use in tractors. In England, David Roberts of Hornsby & Sons, Grantham, obtained a patent for a design in July 1904. In the United States, Holt replaced the wheels on a 40 horsepower (30 kW) Holt steamer, No. 77, with a set of wooden tracks bolted to chains. On November 24, 1904, he successfully tested the updated machine ploughing the soggy delta land of Roberts Island.[13]

When World War I broke out, with the problem of trench warfare and the difficulty of transporting supplies to the front, the pulling power of crawling-type tractors drew the attention of the military.[14] Holt tractors were used to replace horses to haul artillery and other supplies. The Royal Army Service Corps also used them to haul long trains of freight wagons over the unimproved dirt tracks behind the front. Holt tractors were, ultimately, the inspiration for the development of the British and French tanks.[13][15] By 1916, about 1000 of Holt's Caterpillar tractors were used by the British in World War I. Holt vice president Murray M. Baker said that these tractors weighed about 18,000 pounds (8,200 kg) and had 120 horsepower (89 kW).[16] By the end of the war, 10,000 Holt vehicles had been used in the Allied war effort.[17]

French development

The French colonel Jean Baptiste Estienne articulated the vision of a cross-country armoured vehicle on 24 August 1914:[1]: 38

"Victory in this war will belong to the belligerent who is the first to put a cannon on a vehicle capable of moving on all kinds of terrain"

Some privately owned Holt tractors were used by the French Army soon after the start of World War I to pull heavy artillery pieces in difficult terrain.,[1]: 187 but the French did not purchase Holts in large numbers. It was the sight of them in use by the British that later inspired Estienne to have plans drawn up for an armoured body on caterpillar tracks. In the meantime, several attempts were made to design vehicles that could overcome the German barbed wire and trenches.

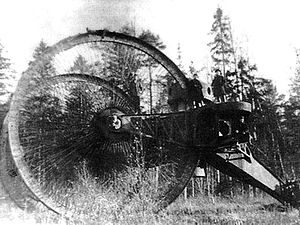

From 1914 to 1915, an early experiment was made with the Boirault machine, with the objective of flattening barbed wire defences and riding over gaps in a battlefield. The machine was made of huge parallel tracks, formed by 4×3 metre metallic frames, rotating around a triangular motorized centre. This device proved too fragile and slow, as well as incapable of changing direction easily, and was abandoned.[6]: 104

In France, on 1 December 1914, M. Frot, an engineer in canal construction at the Compagnie Nationale du Nord, proposed to the French Ministry a design for a "landship" with armour and armament based on the motorisation of a compactor with heavy wheels or rollers. The Frot-Laffly was tested on 18 March 1915, and effectively destroyed barbed wire lines, but was deemed lacking in mobility.[6]: 106–8 The project was abandoned in favour of General Estienne's development using a tractor base, codenamed "Tracteur Estienne".[6]: 108

In 1915, attempts were also made to develop vehicles with powerful armour and armament, mounted on the cross-country chassis of agricultural tractors, with large dented wheels, such as the Aubriot-Gabet "Fortress" (Fortin Aubriot-Gabet). The vehicle was powered by electricity (complete with a supply cable), and armed with a Navy cannon of 37mm, but it too proved impractical.[6]: 109

In January 1915, the French arms manufacturer Schneider & Co. sent out its chief designer, Eugène Brillié, to investigate tracked tractors from the American Holt Manufacturing Company, at that time participating in a test programme in England, for a project of mechanical wire-cutting machines. On his return Brillié, who had earlier been involved in designing armoured cars for Spain, convinced the company management to initiate studies on the development of a Tracteur blindé et armé (armoured and armed tractor), based on the Baby Holt chassis, two of which were ordered.

Experiments on the Holt caterpillar tracks started in May 1915 at the Schneider plant with a 75-hp wheel-directed model and the 45-hp integral caterpillar Baby Holt, showing the superiority of the latter.[6]: 102–11 On 16 June, new experiments followed in front of the President of the Republic, and on 10 September for Commander Ferrus. The first complete chassis with armour was demonstrated at Souain on 9 December 1915, to the French Army, with the participation of colonel Estienne.[5]: 68 [6]: 111 [notes 1]

On 12 December, unaware of the Schneider experiments, Estienne presented to the High Command a plan to form an armoured force, equipped with tracked vehicles. He was put in touch with Schneider, and in a letter dated 31 January 1916 Commander-in-chief Joffre ordered the production of 400 tanks of the type designed by Brillié and Estienne,[6]: 119 although the actual production order of 400 Schneider CA1 was made a bit later on 25 February 1916.[6]: 124 Soon after, on 8 April 1916, another order for 400 Saint-Chamond tanks was also placed.[6]: 128 Schneider had trouble with meeting production schedules, and the tank deliveries were spread over several months from 8 September 1916.[6]: 124 The Saint-Chamond tank would start being delivered from 27 April 1917.[6]: 130

British development

The Lincolnshire firm Richard Hornsby & Sons had been developing the caterpillar tractor since 1902, and built an oil engine powered crawler to move lifeboats up a beach in 1908. In 1909 The Northern Light and Power Company of Dawson City, Canada, owned by Joe Boyle, ordered a steam powered caterpillar tractor. It was delivered to the Yukon in 1912. Hornsby's tractors were trialled between 1905 and 1910 on several occasions with the British Army as artillery tractors, but not adopted. Hornsby sold its patents to Holt Tractor of California.

In 1914, the British War Office ordered a Holt tractor and put it through trials at Aldershot. Although it was not as powerful as the 105 horsepower (78 kW) Foster-Daimler tractor, the 75 horsepower (56 kW) Holt was better suited to haul heavy loads over uneven ground. Without a load, the Holt tractor managed a walking pace of 4 miles per hour (6.4 km/h). Towing a load, it could manage 2 miles per hour (3.2 km/h). Most importantly, Holt tractors were readily available in quantity.[18] The War Office was suitably impressed and chose it as a gun-tractor.[18]

In July 1914, Lt. Col. Ernest Swinton, a British Royal Engineer officer, learned about Holt tractors and their transportation capabilities in rough terrain from a friend who had seen one in Antwerp, but passed the information on to the transport department.[19]: 12 [20]: 590 When the First World War broke out, Swinton was sent to France as the Army's war correspondent and in October 1914 identified the need for what he described as a "machine-gun destroyer" - a cross-country, armed vehicle.[19]: 116 [19]: 12 He remembered the Holt tractor, and decided that it could be the basis for an armoured vehicle.

Swinton proposed in a letter to Sir Maurice Hankey, Secretary of the Committee of Imperial Defence, that the British Committee of Imperial Defence build a power-driven, bullet-proof, tracked vehicle that could destroy enemy guns.[19][21]: 129 Hankey persuaded the lukewarm War Office to make a trial on 17 February 1915 with a Holt tractor, but the caterpillar bogged down in the mud, the project was abandoned, and the War Office gave up investigations.[5]: 25 [21]: 129

In May 1915, the War Office made new tests on a trench-crossing machine: the Tritton Trench-Crosser. The machine was equipped with large tractor wheels, 8 feet in diameter, and carried girders on an endless chain which were lowered above a trench so that the back wheels could roll over it. The machine would then drag the girder behind until on flat terrain, so that it could reverse over them and set them back in place in front of the vehicle. The machine proved much too cumbersome and was abandoned.[5]: 143–144

Winston Churchill, First Lord of the Admiralty, learned of the armoured tractor idea, he reignited investigation of the idea of using the Holt tractor. The Royal Navy and the Landships Committee (established on 20 February 1915),[22] at last agreed to sponsor experiments and tests of armoured tractors as a type of "land ship". In March, Churchill ordered the building of 18 experimental landships: 12 using Diplock pedrails (an idea promoted by Murray Sueter), and 6 using large wheels (the idea of T.G. Hetherington).[5]: 25 Construction however failed to move forward, as the wheels seemed impractical after a wooden mock-up was realized: the wheels were initially planned to be 40-feet in diameter, but turned out to be still too big and too fragile at 15-feet.[5]: 26–27 The pedrails also met with industrial problems,[23]: 23–24 and the system was deemed too large, too complicated and under-powered.[5]: 26

Instead of choosing to use the Holt tractor, the British government chose to involve a British agricultural machinery firm, Foster and Sons, whose managing director and designer was Sir William Tritton.[18]

After all these projects failed by June 1915, ideas of grandiose landships were abandoned, and a decision was taken to make an attempt with US Bullock Creeping Grip caterpillar tracks, by connecting two of them together to obtain an articulated chassis deemed necessary for manoeuvring. Experiments failed in tests made in July 1915.[5]: 25

Another experiment was conducted with an American Killen-Strait tracked tractor. A wire-cutting mechanism was successfully fitted, but the trench-crossing capability of the vehicle proved insufficient. A Delaunay-Belleville armoured car body was fitted, making the Killen-Strait machine the first armoured tracked vehicle, but the project was abandoned as it turned out to be a blind alley, unable to fulfil all-terrain warfare requirements.[5]: 25

After these experiments, the Committee decided to build a smaller experimental landship, equivalent to one half the articulated version, and using lengthened US-made Bullock Creeping Grip caterpillar tracks.[5]: 27 [23]: 27–28 This new experimental machine was called the No1 Lincoln Machine: construction started on 11 August 1915, with the first trials starting on 10 September 1915.[5]: 26 These trials failed however because of unsatisfactory tracks.[23]: 29

Development continued with new, re-engineered tracks designed by William Tritton,[23]: 29 and the machine, now renamed Little Willie,[23]: 30 was completed in December 1915 and tested on 3 December 1915. Trench-crossing ability was deemed insufficient however, and Walter Gordon Wilson developed a rhomboidal design,[23]: 30 which became known as "His Majesty's Landship Centipede" and later "Mother",[23]: 30 the first of the "Big Willie" types of true tanks. After completion on 29 January 1916 very successful trials were made, and an order was placed by the War Office for 100 units to be used on the Western front in France,[20]: 590 [21]: 129 on 12 February 1916,[6]: 216 and a second order for 50 additional units was placed in April 1916.[24]

France started studying caterpillar continuous tracks from January 1915, and actual tests started in May 1915,[6]: 102–111 two months earlier than the Little Willie experiments. At the Souain experiment, France tested an armoured tracked tank prototype, the same month Little Willie was completed.[6]: 111 Ultimately however, the British were the first to put tanks on the battlefield, at the battle of the Somme in September 1916.

The name "tank" was introduced in December, 1915 as a security measure and has been adopted in many languages. William Tritton, stated that when the prototypes were under construction from August, 1915 they were deliberately falsely described in order to conceal their true purpose.[25] In the workshop the paperwork described them as "water carriers," supposedly for use on the Mesopotamian Front. In conversation the workers referred to them as "water tanks" or, simply, "tanks." In October the Landships Committee decided, for security purposes, to change its own name to something less descriptive.[26] One of the members, Ernest Swinton[27]) suggested "tank," and the committee agreed. The name "tank" was used in official documents and common parlance from then on, and the Landships Committee was renamed the Tank Supply Committee. This is sometimes confused with the labelling of the first production tanks (ordered in February, 1916) with a caption in Russian. It translated as "With Care to Petrograd," probably again inspired by the workers at Foster's, some of whom believed the machines to be snowploughs meant for Russia, and was introduced from May 15, 1916. The Committee was happy to perpetuate this misconception since it might also mislead the Germans.[28]

The naval background of the tank's development also explains such nautical tank terms as hatch, hull, bow, and ports. The great secrecy surrounding tank development, coupled with the scepticism of infantry commanders, often meant that infantry at first had little training to cooperate with tanks.

Russian development

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (April 2011) |

Vasily Mendeleev, an engineer in a shipyard, worked privately on a design of a super-heavy tank from 1911 to 1915. It was a heavily armoured 170 ton tracked vehicle armed with one 120 mm naval gun. The design envisioned many innovations that became standard features of a modern battle tank – protection of the vehicle was well-thought out, the gun included automatic loading mechanism, pneumatic suspension allowed adjusting of clearance, some critical systems were duplicated, transportation by railroad was possible by a locomotive or with adapter wheels. However, the cost was almost as much as a submarine and it was never built.[29][30]

The Vezdekhod was a small cross-country vehicle designed by aero-engineer Aleksandr Porokhovschikov that ran on a single wide rubber track propelled by a 10 hp engine. Two small wheels either side were provided for steering but while the vehicles could cross ground well its steering was ineffectual. In post-revolution Russia, the Vezdekhod was portrayed in propaganda as the first tank.

The Tsar Tank, also known as the Lebedenko tank after its designer – was a tricycle design vehicle on 9 m high front wheels. It was expected that such large wheels would be able to cross any obstacle but the smaller rear wheel became stuck when tested in 1915. The designers were prepared to fit larger engines but the project – and the vehicle – was abandoned.

German Development

The A7V was the only German tank of World War I. It was made in the year 1918. The A7V was produced in small numbers.[31]

Operational use in World War I

A first offensive using Mark I tanks took place on 15 September 1916, during the Battle of the Somme. Forty-nine were committed, of which 32 were mechanically fit to take part in the advance and achieved some small, local successes.[32]: 1153 In July 1917, 216 British tanks were employed in the Third Battle of Ypres but found it almost impossible to operate in the muddy conditions and achieved little. Not until 20 November 1917, at Cambrai, did the British Tank Corps get the conditions it needed for success. Over 400 tanks penetrated almost six miles on a 7-mile wide front. However, success was not complete because the infantry failed to exploit and secure the tanks' gains, and almost all the territory gained was recaptured by the Germans. The British scored a far more significant victory the following year, on 8 August 1918, with 600 tanks in the Battle of Amiens. General Erich Ludendorff referred to that date as the "Black Day" of the German Army.

Parallel to the British development, France designed its own tanks. The first two, the medium Schneider CA and heavy Saint-Chamond, were not well-conceived, though produced in large numbers and showing technical innovations, the latter using an electro-mechanical transmission and a long 75 mm gun. Both types saw action on numerous occasions but suffered consistently high losses. In 1918 the Renault FT light tank was the first tank in history with a "modern" configuration: a revolving turret on top and an engine compartment at the rear; it would be the most numerous tank of the war. A last development was the superheavy Char 2C, the largest tank ever to see service, be it some years after the armistice.

The German response to the Cambrai assault was to develop its own armoured program. Soon the massive A7V appeared. The A7V was a clumsy monster, weighing 30 tons and with a crew of eighteen. By the end of the war, only twenty had been built. Although other tanks were on the drawing board, material shortages limited the German tank corps to these A7Vs and about 36 captured Mark IVs. The A7V would be involved in the first tank vs. tank battle of the war on April 24, 1918 at the Second Battle of Villers-Bretonneux—a battle in which there was no clear winner.

Numerous mechanical failures and the inability of the British and French to mount any sustained drives in the early tank actions cast doubt on their usefulness—and by 1918, tanks were extremely vulnerable unless accompanied by infantry and ground-attack aircraft, both of which worked to locate and suppress anti-tank defences.

But Gen. John J. Pershing, Commander in Chief, American Expeditionary Forces (AEF), requested in September 1917 that 600 heavy and 1,200 light tanks be produced in the United States. When General Pershing assumed command of the American Expeditionary Force and went to France, he took Lt. Col. George Patton. Patton became interested in tanks. They were then unwieldy, unreliable, and unproved instruments of warfare, and there was much doubt whether they had any function and value at all on the battlefield. Against the advice of most of his friends, Patton chose to go into the newly formed US Tank Corps. He was the first officer so assigned.

The first American-produced heavy tank was the 43.5-ton Mark VIII (sometimes known as the "Liberty"), a US-British development of the successful British heavy tank design, intended to equip the Allied forces. Armed with two 6-pounder cannons and five rifle-caliber machine guns, it was operated by an 11-man crew, and had a maximum speed of 6.5 miles per hour and a range of 50 miles. Because of production difficulties, only test vehicles were completed before the War ended. The American-built 6.5-ton M1917 light tank was a close copy of the French Renault FT. It had a maximum speed of 5.5 miles per hour and could travel 30 miles on its 30-gallon fuel capacity. Again, because of production delays, none were completed in time to see action. In the summer of 1918 a 3-ton, 2-man tank, (Ford 3-Ton M1918) originated by the Ford Motor Company was designed. It was powered by two Ford Model T, 4-cylinder engines, armed with a .30 inch machine gun, and had a maximum speed of 8 miles per hour. It was considered unsatisfactory as a fighting vehicle but to have possible value in other battlefield roles. An order was placed for 15,000, but only 15 were completed, and none saw service in the War.

American tank units first entered combat on 12 September 1918 against the St. Mihiel salient with the First Army. They belonged to the 344th and 345th Light Tank Battalions, elements of the 304th Tank Brigade, commanded by Lt. Col. Patton, under whom they had trained at the tank center in Bourg, France, and were equipped with the Renault FT, supplied by France. Although mud, lack of fuel, and mechanical failure caused many tanks to stall in the German trenches, the attack succeeded and much valuable experience was gained. By the armistice of 11 November 1918, the AEF was critically short of tanks, as no American-made ones were completed in time for use in combat.

Interwar period

After World War I, General Erich Ludendorff of the German High Command praised the Allied tanks as being a principal factor in Germany's defeat. The Germans had been too late in recognizing their value to consider them in their own plans. Even if their already hard-pressed industry could have produced them in quantity, fuel was in very short supply. Of the total of 90 tanks fielded by the Germans during 1918, 75 had been captured from the Allies.

At the war's end, the main role of the tank was considered to be that of close support for the infantry. The U.S. tank units fought so briefly and were so fragmented during the war, and the number of tanks available to them was so limited, that there was practically no opportunity to develop tactics for their large-scale employment. Nonetheless, their work was sufficiently impressive to imbue at least a few military leaders with the idea that the use of tanks in mass was the most likely principal role of armour in the future.

Highlights of U.S. Army appraisal for the development and use of tanks, developed from combat experience, were: (1) the need for a tank with more power, fewer mechanical failures, heavier armour, longer operating range, and better ventilation; (2) the need for combined training of tanks with other combat arms, especially the infantry; (3) the need for improved means of communication and of methods for determining and maintaining directions; and (4) the need for an improved supply system, especially for petrol and ammunition.

Although the tank of World War I was slow, clumsy, unwieldy, difficult to control, and mechanically unreliable, its value as a combat weapon had been clearly proven. But, despite the lessons of World War I, the combat arms were most reluctant to accept a separate and independent role for armor and continued to struggle among themselves over the proper use of tanks. At the outset, thought of the tank as an auxiliary to and a part of the infantry was the predominant opinion, although a few leaders contended that an independent tank arm should be retained.

In addition to the light and heavy categories of American-produced tanks of World War I, a third classification, the medium, began receiving attention in 1919. It was hoped that this in-between type would incorporate the best features of the 6½-ton light and the Mark VIII heavy and would replace both. The meaning of the terms light, medium, and heavy tanks changed between the wars. During World War I and immediately thereafter, the light tank was considered to be up to 10 tons, the medium (produced by the British) was roughly between 10 and 25 tons, and the heavy was over 25 tons. For World War II, increased weights resulted in the light tank being over 20 tons, the medium over 30, and the heavy, developed toward the end of the war, over 60 tons. During the period between the world wars, the weights of the classifications varied generally within these extremes.

The U.S. National Defense Act of 1920 placed the Tank Corps under the Infantry. The Act's stipulation that "hereafter all tank units shall form a part of the Infantry" left little doubt as to the tank role for the immediate future. George Patton had argued for an independent Tank Corps. But if, in the interest of economy, the tanks had to go under one of the traditional arms, he preferred the cavalry, for Patton intuitively understood that tanks operating with cavalry would stress mobility, while tanks tied to the infantry would emphasize firepower. Tanks in peacetime, he feared, as he said, "would be very much like coast artillery with a lot of machinery which never works."

At a time when most soldiers regarded the tank as a specialized infantry-support weapon for crossing trenches, a significant number of officers in the Royal Tank Corps had gone on to envision much broader roles for mechanized organizations. In May 1918, Col. J.F.C. Fuller, the acknowledged father of tank doctrine, had used the example of German infiltration tactics to refine what he called "Plan 1919". This was an elaborate concept for a large-scale armoured offensive in 1919.

The Royal Tank Corps had to make do with the same basic tanks from 1922 until 1938. British armoured theorists did not always agree with each other. B. H. Liddell Hart, a noted publicist of armoured warfare, wanted a true combined arms force with a major role for mechanized infantry. Fuller, Broad, and other officers were more interested in a pure-tank role. The Experimental Mechanized Force formed by the British to investigate and develop techniques was a mobile force with its own self-propelled guns, supporting infantry and engineers in motor vehicles and armoured cars.

Both advocates and opponents of mechanization often used the term "tank" loosely to mean not only an armored, tracked, turreted, gun-carrying fighting vehicle, but also any form of armored vehicle or mechanized unit. Such usage made it difficult for contemporaries or historians to determine whether a particular speaker was discussing pure tank forces, mechanized combined arms forces, or mechanization of infantry forces.

British armoured vehicles tended to maximize either mobility or protection. Both the cavalry and the Royal Tank Corps wanted fast, lightly armoured, mobile vehicles for reconnaissance and raiding—the light and medium (or "cruiser") tanks. In practice the "light tanks" were often small armoured personnel carriers. On the other hand, the "army tank battalions" performing the traditional infantry-support role required extremely heavy armoured protection. As a consequence of these two doctrinal roles, firepower was neglected[citation needed] in tank design.

Among the German proponents of mechanization, General Heinz Guderian was probably the most influential. Guderian's 1914 service with radiotelegraphs in support of cavalry units led him to insist on a radio in every armoured vehicle. By 1929, when many British students of armour were tending towards a pure armour formation, Guderian had become convinced that it was useless to develop just tanks, or even to mechanize parts of the traditional arms. What was needed was an entirely new mechanized formation of all arms that would maximize the effects of the tank.

The German tanks were not up to the standards of Guderian's concept. The Panzer I was really a machine-gun-armed tankette, derived from the British Carden-Loyd personnel carrier. The Panzer II did have a 20-mm cannon, but little armour protection. These two vehicles made up the bulk of panzer units until 1940.

In the twenties France was the only country in the world with a large armour force. French doctrine viewed combined arms as a process by which all other weapons systems assisted the infantry in its forward progress. Tanks were considered to be "a sort of armoured infantry", by law subordinated to the infantry branch. This at least had the advantage that armour was not restricted purely to tanks; the French army would be among the most mechanised. Tanks proper were however first of all seen as specialised breakthrough systems, to be concentrated for an offensive: light tanks had to limit their speed to that of the foot soldier; heavy tanks were intended to form a forward "shock front" to dislodge defensive lines. The doctrine was much preoccupied with the strength of the defender: artillery and air bombardments had to destroy machine guns and anti-tank guns. The envelopment phase was neglected. Though part of the Infantry branch, tanks were in fact concentrated in almost pure tank units and rarely trained together with foot soldiers.

In 1931, France decided to produce armour and other equipment in larger quantities, including the Char B1 bis. The B1 bis, developed by Estienne in the early 1920s, was still one of the most powerful tank designs in the world fifteen years later. In 1934 the French cavalry also began a process of mechanisation; tanks were to be used for exploitation also.

As the French Army was moving forward in the area of mechanization, doctrinal strife began to develop. In 1934, Lieutenant Colonel Charles de Gaulle published Towards the Professional Army. De Gaulle favoured a professional mechanised force, capable of executing both the breakthrough and the exploitation phase. He envisioned a pure armour brigade operating in linear formation, followed by a motorized infantry force for mopping-up. His ideas were not adopted, as being too expensive.

From 1936 French tank production accelerated, but the doctrinal problems remained, resulting in 1940 in an inflexible structure, with the Infantry and Cavalry fielding separate types of armoured division.

During the course of the 1920s and early 1930s, a group of Soviet officers led by Marshal Mikhail Tukhachevsky developed a concept of "Deep Battle" to employ conventional infantry and cavalry divisions, mechanized formations, and aviation in concert. Using the expanded production facilities of the Soviet government's first Five Year Plan with design features taken in part from the American inventor J. Walter Christie, the Soviets produced 5,000 armoured vehicles by 1934. This wealth of equipment enabled the Red Army to create tank organizations for both infantry support and combined arms, mechanized operations.

On 12 June 1937, the Soviet government executed Tukhachevsky and eight of his high-ranking officers, as Stalin shifted his purge of Soviet society against the last power group that had the potential to threaten him, the Red Army. At the same time, the Soviet experience in the Spanish Civil War caused the Red Army to reassess mechanization. The Soviet tanks were too lightly armoured, their Russian crews could not communicate with the Spanish troops, and in combat the tanks tended to outpace the supporting infantry and artillery.

The United States was not nearly so advanced in the development of armoured and mechanized forces. As in France, the supply of slow World War I tanks and the subordination of tanks to the infantry branch impeded the development of any role other than direct infantry support. The US War Department policy statement, which finally came in April 1922, was a serious blow to tank development. Reflecting prevailing opinion, it stated that the tank's primary mission was "to facilitate the uninterrupted advance of the riflemen in the attack." The War Department considered that two types of tanks, the light and the medium, should fulfill all missions. The light tank was to be truck transportable and not exceed 5 tons gross weight. For the medium, restrictions were even more stringent; its weight was not to exceed 15 tons, so as to bring it within the weight capacity of railroad flatcars, the average existing highway bridge, and, most significantly, available Engineer Corps pontoon bridges.

Although an experimental 15-ton tank, the M1924, reached the mock-up stage, this and other attempts to satisfy War Department and infantry specifications proved to be unsatisfactory. In reality it was simply impossible to build a 15-ton vehicle meeting both War Department and infantry requirements.

In 1926 the General Staff reluctantly consented to the development of a 23-ton tank, although it made clear that efforts were to continue toward the production of a satisfactory 15-ton vehicle. The infantry—its new branch chief overriding the protests of some of his tankmen who wanted a more heavily armed and armored medium—decided, too, that a light tank, transportable by truck, best met infantry requirements. The net effect of the infantry's preoccupation with light tanks and the limited funds available for tank development in general was to slow the development of heavier vehicles and, ultimately, to contribute to the serious shortage of mediums at the outbreak of World War II.

J. Walter Christie was an innovative designer of tanks, engines and propulsion systems. Although his designs did not meet US Army specifications, other countries used his chassis patents. Despite inadequate funding, the Ordnance Department managed to develop several experimental light and medium tanks and tested one of Walter Christie's models by 1929. None of these tanks was accepted, usually because each of them exceeded standards set by other Army branches. For instance, several light tank models were rejected because they exceeded the 5-ton cargo capacity of the Transportation Corps trucks, and several medium tank designs were rejected because they exceeded the 15-ton bridge weight limit set by the engineers. Christie simply would not work with users to fulfill the military requirements but, instead, wanted the Army to fund the tanks that he wanted to build. Patton later worked closely with J. Walter Christie to improve the silhouette, suspension, power, and weapons of tanks.

The Christie tank embodied the ability to operate both on tracks and on large, solid-rubber-tired bogie wheels. The tracks were removable to permit operation on wheels over moderate terrain. Also featured was a suspension system of independently sprung wheels. The Christie had many advantages, including the amazing ability, in 1929, to attain speeds of 69 miles per hour on wheels and 42 miles per hour on tracks, although at these speeds the tank could not carry full equipment. To the infantry and cavalry the Christie was the best answer to their need for a fast, lightweight tank, and they were enthusiastic about its convertibility. On the other hand, the Ordnance Department, while recognizing the usefulness of the Christie, was of the opinion that it was mechanically unreliable and that such dual-purpose equipment generally violated good engineering practice. The controversy over the advantages and drawbacks of Christie tanks raged for more than twenty years, with the convertible principle being abandoned in 1938. But the Christie ideas had great impact upon tank tactics and unit organization in many countries and, finally, upon the US Army as well.

In the United States the real beginning of the Armored Force was in 1928, twelve years before it was officially established, when Secretary of War Dwight F. Davis directed that a tank force be developed in the Army. Earlier that year he had been much impressed, as an observer of maneuvers in England, by a British experimental armoured Force. Actually the idea was not new. A small group of dedicated officers in the cavalry and the infantry had been hard at work since World War I on theories for such a force. The continued progress in the design of armour, armament, engines, and vehicles was gradually swinging the trend toward more mechanization, and the military value of the horse declined. Proponents of mechanization and motorization pointed to advances in the motor vehicle industry and to the corresponding decrease in the use of horses and mules. Furthermore, abundant oil resources gave the United States an enviable position of independence in fuel requirements for the machines.

Secretary Davis' 1928 directive for the development of a tank force resulted in the assembly and encampment of an experimental mechanized force at Camp Meade, Maryland, from 1 July to 20 September 1928. The combined arms team consisted of elements furnished by Infantry (including tanks), Cavalry, Field Artillery, the Air Corps, Engineer Corps, Ordnance Department, Chemical Warfare Service, and Medical Corps. An effort to continue the experiment in 1929 was defeated by insufficient funds and obsolete equipment, but the 1928 exercise did bear fruit, for the War Department Mechanization Board, appointed to study results of the experiment, recommended the permanent establishment of a mechanized force.

As Chief of Staff from 1930 to 1935, Douglas MacArthur wanted to advance motorization and mechanization throughout the army. In late 1931 all arms and services were directed to adopt mechanization and motorization, "as far as is practicable and desirable", and were permitted to conduct research and to experiment as necessary. Cavalry was given the task of developing combat vehicles that would "enhance its power in roles of reconnaissance, counterreconnaissance, flank action, pursuit, and similar operations." By law, "tanks" belonged to the infantry branch, so the cavalry gradually bought a group of "combat cars", lightly armoured and armed tanks that were often indistinguishable from the newer infantry "tanks."

In 1933 MacArthur set the stage for the coming complete mechanization of the cavalry, declaring, "The horse has no higher degree of mobility today than he had a thousand years ago. The time has therefore arrived when the Cavalry arm must either replace or assist the horse as a means of transportation, or else pass into the limbo of discarded military formations." Although the horse was not yet claimed to be obsolete, his competition was gaining rapidly, and realistic cavalrymen, sensing possible extinction, looked to at least partial substitution of the faster machines for horses in cavalry units.

The War Department in 1938 modified its 1931 directive for all arms and services to adopt mechanization and motorization. Thereafter, development of mechanization was to be accomplished by two of the combat arms only—the cavalry and the infantry. As late as 1938, on the other hand, the Chief of Cavalry, Maj. Gen. John K. Herr, proclaimed, "We must not be misled to our own detriment to assume that the untried machine can displace the proved and tried horse." He favored a balanced force made up of both horse and mechanized cavalry. In testimony before a Congressional committee in 1939, Maj. Gen. John K. Herr maintained that horse cavalry had "stood the acid test of war", whereas the motor elements advocated by some to replace it had not.

Actually, between the world wars there was much theoretical but little tangible progress in tank production and tank tactics in the United States. Production was limited to a few hand-tooled test models, only thirty-five of which were built between 1920 and 1935. Regarding the use of tanks with infantry, the official doctrine of 1939 largely reiterated that of 1923. It maintained that "As a rule, tanks are employed to assist the advance of infantry foot troops, either preceding or accompanying the infantry assault echelon."

In the 1930s the American Army began to seriously discuss the integration of the tank and the airplane into existing doctrine, but the US Army remained an infantry-centered Army, even though sufficient changes had occurred to warrant serious study. In the spring of 1940, maneuvers in Georgia and Louisiana, where Patton was an umpire, showed how far Chaffee had brought the development of American armoured doctrine.

World War II

World War II forced armies to integrate all the available arms at every level into a mobile, flexible team. The mechanized combined arms force came of age in this war. In 1939, most armies still thought of an armoured division as a mass of tanks with relatively limited support from the other arms. By 1943, the same armies had evolved armoured divisions that were a balance of different arms and services, each of which had to be as mobile and almost as protected as the tanks they accompanied. This concentration of mechanized forces in a small number of mobile divisions left the ordinary infantry unit deficient in armour to accompany the deliberate attack. The German, Soviet, and American armies therefore developed a number of tank surrogates such as tank destroyers and assault guns to perform these functions in cooperation with the infantry.

Armour experts in most armies, however, were determined to avoid being tied to the infantry, and in any event a tank was an extremely complicated, expensive, and therefore scarce weapon. The British persisted for much of the war on a dual track of development, retaining Infantry tanks to support the infantry and lighter, more mobile cruiser tanks for independent armoured formations. The Soviets similarly produced an entire series of heavy breakthrough tanks.

During the war, German tank design went through at least three generations, plus constant minor variations. The first generation included such prewar vehicles as the Panzerkampfwagen (or Panzer) I and II, which were similar to Soviet and British light tanks. The Germans converted their tank battalions to a majority of Panzer III and Panzer IV medium tanks after the 1940 French campaign. However, the appearance of large numbers of the new generation T-34 and KV-1 Soviet tanks, that were unknown to Germans until 1941, compelled them to join a race for superior armour and gun power. The third generation included many different variants, but the most important designs were the Panther (Panzer V) and Tiger (Panzer VI) tanks. Unfortunately for the Germans, lack of resources combined with emphasis on protection and firepower and a penchant for overly complex design philosophies in nearly every part of an armoured fighting vehicle's design compromised the production numbers. In 1943, for example, Germany manufactured only 5,966 tanks, as compared to 29,497 for the US, 7,476 for Britain, and an estimated 20,000[citation needed] for the Soviet Union. However, an assault gun casemate-hulled development of the Panzer III, the Sturmgeschütz III, would turn out to be Germany's most-produced armoured fighting vehicle of any type during the war, at just over 9,300 examples, a popular design which could also be very effectively tasked to perform the duties of a dedicated anti-tank vehicle.

The alternative to constant changes in tank design was to standardize a few basic designs and mass-produce them even though technology had advanced to new improvements. This was the solution of Germany's principal opponents. The Soviet T-34, for example, was an excellent basic design that survived the war with only one major change in armament, 76.2-mm to 85-mm main gun.

The United States had even more reason to standardize and mass-produce than did the Soviet Union. By concentrating on mechanical reliability, the US was able to produce vehicles that operated longer with fewer repair parts. To ensure that American tanks were compatible with American bridging equipment, the War Department restricted tank width and maximum weight to thirty tons. The army relaxed these requirements only in late 1944.

When Germany invaded western Europe in 1940, the US Army had only 28 new tanks – 18 medium and 10 light – and these were soon to become obsolete, along with some 900 older models on hand. The Army had no heavy tanks and no immediate plans for any. Even more serious than the shortage of tanks was industry's lack of experience in tank manufacture and limited production facilities. Furthermore, the United States was committed to helping supply its allies. By 1942 American tank production had soared to just under 25,000, almost doubling the combined British and German output for that year. And in 1943, the peak tank production year, the total was 29,497. All in all, from 1940 through 1945, US tank production totaled 88,410.

Tank designs of World War II were based upon many complex considerations, but the principal factors were those thought to be best supported by combat experience. Among these, early combat proved that a bigger tank was not necessarily a better tank. The development goal came to be a tank combining all the proven characteristics in proper balance, to which weight and size were only incidentally related. The key characteristics were mechanical reliability, firepower, mobility and protection.

The problem here was that only a slight addition to the thickness of armour plate greatly increased the total weight of the tank, thereby requiring a more powerful and heavier engine. This, in turn, resulted in a larger and heavier transmission and suspension system. Just this sort of "vicious circle" aimed at upgrading a tank's most vital characteristics tended to make the tank less maneuverable, slower, and a larger and easier target. Determining the point at which the optimum thickness of armour was reached, in balance with other factors, presented a challenge that resulted in numerous proposed solutions and much disagreement.

According to Lt. Gen. Lesley J. McNair, Chief of Staff of GHQ, and later Commanding General, Army Ground Forces, the answer to bigger enemy tanks was more powerful guns instead of increased size.

Since emphasis of the using arms was upon light tanks during 1940 and 1941, their production at first was almost two to one over the mediums. But in 1943, as the demand grew for more powerful tanks, the lights fell behind, and by 1945 the number of light tanks produced was less than half the number of mediums.

In 1945–46, the General Board of the US European Theater of Operations conducted an exhaustive review of past and future organization. The tank destroyer was deemed too specialized to justify in a peacetime force structure. In a reversal of previous doctrine, the US Army concluded that "the medium tank is the best antitank weapon." Although such a statement may have been true, it ignored the difficulties of designing a tank that could outshoot and defeat all other tanks.

The Cold War

In the Cold War, the two opposing forces in Europe were the Warsaw Pact countries on the one side, and the NATO countries on the other side.

Soviet domination of the Warsaw Pact led to effective standardization on a few tank designs. In comparison, NATO adopted a defensive posture. The major contributing nations, France, Germany, the USA, and the UK developed their own tank designs, with little in common.

After World War II, tank development continued. Tanks would not only continue to be produced in huge numbers, but the technology advanced dramatically as well. Medium tanks became heavier, their armour became thicker and their firepower increased. This led gradually to the concept of the main battle tank and the gradual elimination of the heavy tank. Aspects of gun technology changed significantly as well, with advances in shell design and effectiveness.

Many of the changes in tank design have been refinements to targeting and ranging (fire control), gun stabilization, communications and crew comfort. Armour evolved to keep pace with improvements in weaponry – the rise of composite armour is of particular note – and guns grew more powerful. However, basic tank architecture did not change significantly, and has remained largely the same into the 21st century.

Post-Cold War

With the end of the Cold War in 1991, questions once again started sprouting concerning the relevance of the traditional tank. Over the years, many nations cut back the number of their tanks or replaced most of them with lightweight armoured fighting vehicles with only minimal armour protection.

This period also brought an end to the superpower blocs, and the military industries of Russia and Ukraine are now vying to sell tanks worldwide. India and Pakistan have upgraded old tanks and bought new T-84s and T-90s from the former Soviet states. Both have demonstrated prototypes that the respective countries are not adopting for their own use, but are designed exclusively to compete with the latest western offerings on the open market.

Ukraine has developed the T-84-120 Oplot, which can fire both NATO 120 mm ammunition and ATGMs through the gun barrel. It has a new turret with auto-loader, but imitates western designs with an armoured ammunition compartment to improve crew survivability.

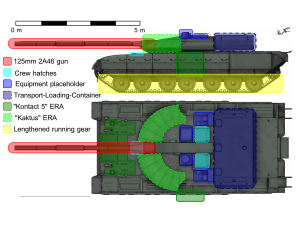

The Russian Chyorny Oryol ("Black Eagle") is based on a lengthened T-80 hull. An early mock-up, shown for the first time at the second VTTV-Omsk-97 International Exhibition of Armaments in 1997, appears to have dramatically heavier armour, and a completely new modern turret separating crew and ammunition. The prototype has a 125 mm tank gun, but is said to be able to mount a new 152 mm gun. Russia is also rumoured to be developing the Obiekt 775 MBT, sometimes called T-95, with a remote-controlled turret, for domestic service.

The Italian C1 Ariete MBT was among the latest all-new MBTs to be fielded, with deliveries running from 1995 to 2002. The tank is nearly the same size of the very first tank, both being 8 feet (2.5 m) high. The Mark I had a ~9.9 m long (hull) and the Ariete as a 7.6/9.52 m long (hull/hull+gun). However, the Ariete weighs over double and can travel ten times faster, 54,000 kg vs. 25,401 kg and 40 mph vs. 4 mph (60 v 6 km/h).

A number of armies have considered eliminating tanks completely, reverting to a mix of wheeled anti-tank guns and infantry fighting vehicles (IFV), though in general there is a great deal of resistance because all of the great powers still maintain large numbers of them, in active forces or in ready reserve. There has been no proven alternative, and tanks have had a relatively good track record in recent conflicts.

The tank continues to be vulnerable to many kinds of anti-tank weapons and is more logistically demanding than lighter vehicles, but these were traits that were true for the first tanks as well. In direct fire combat they offer an unmatched combination of higher survivability and firepower among ground-based warfare systems. Whether this combination is particularly useful in proportion to their cost is matter of debate, as there also exist very effective anti-tank systems, IFVs, and competition from air-based ground attack systems.

Due to vulnerability from RPG's, the tank has always had local defense from machine guns to solve the problem. This partially solved the problem in some cases, but produced another. Because the machine gun had to be operated by the commander from outside the tank, it made him vulnerable to enemy fire. To solve this problem, gun shields were made to reduce this threat, but did not completely solve the problem. So, when the development of the M1A2 TUSK (Tank Urban Survival Kit) came, the finalization of a remote machine gun came into place, and was one of the first main battle tanks to have one. Other examples of this gun have been seen, such as a 20 mm remote cannon on the M60A2. This remote machine gun, under the name CROWS (Common Remotely Operated Weapons Station) has solved the problem of enemy fire threat to the commander, when operating the machine gun. It can also be equipped with an optional grenade launcher.

Possibly one of the main evolution sources for tanks in this century are the active protection systems. Until 15 years ago, armour (reactive or passive) was the only effective measure against anti-tank assets. The most recent active protection systems (including Israeli TROPHY and Iron Fist and Russian Arena) offer high survivability even against volleys of RPG and missiles. If these kinds of systems evolve further and are integrated in contemporary tank and armoured vehicle fleets, the armour-antitank equation will change completely; therefore, 21st century tanks would experience a total revival in terms of operational capabilities.

See also

- Tank classification

- G-numbers (U.S. tanks)

- Tank guns

- Comparison of World War I tanks

- Tanks of the interwar period

- Comparison of early World War II tanks

- Post-Cold War Tanks

- Armoured fighting vehicle

- Cultivator No. 6

Notes

- ^ On December 9, 1915, the Baby Holt, modified with a mock-up armoured driving position... was demonstrated on a crosscountry course at Souain. (Armoured Fighting Vehicles of the World)

References

- ^ a b c d Gudmundsson, Bruce I. (2004). On Armor. Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 0-275-95019-0.

- ^ Williamson Murray, "Armored Warfare: The British, French, and German Experiences," in Murray, Williamson; Millet, Allan R, eds. (1996). Military Innovation in the Interwar Period. New York: Cambridge University Press. p. 6. ISBN 0-521-63760-0.

- ^ Collision of empires Arnold D. Harvey p.381

- ^ Sedlar, Jean W. (1994), A history of East Central Europe: East Central Europe in the Middle Ages, University of Washington Press. p. 234. ISBN 0-295-97290-4

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Fletcher, David; Crow, Duncan; Duncan, Maj Gen NW (1970). Armoured Fighting Vehicles of the World: AFVs of World War One. Cannon Books. ISBN 1-899695-02-8.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q Gougaud, Alain (1987). L'Aube de la Gloire, Les Autos-Mitrailleuses et les Chars Français pendant la Grande Guerre. Musée des Blindés. ISBN 2-904255-02-8.

- ^ Fletcher, David (January 1, 1970). Armoured Fighting Vehicles in Profile Volume I AFV's in World War One. Profile Publications. ASIN B002MQY6BE.

- ^ Wells, HG (1917). "V. Tanks". War and the Future. Cassell & Co.

- ^ Wells, HG (December 1903). The Land Ironclads.

- ^ "Agricultural Machinery, Business History of Machinery Manufacturers".

- ^ "Benjamin Holt" (PDF). Production Technology. 2008-09-25. Retrieved 2010-02-24.

- ^ Backus, Richard (August–September 2004). "''100 Years on Track'' 2004 Tulare Antique Farm Equipment Show". Farm Collector. Gas Engine Magazine. Retrieved 2010-02-04.

- ^ a b Pernie, Gwenyth Laird (March 3, 2009). "Benjamin Holt (1849–1920): The Father of the Caterpillar tractor".

- ^ "Pliny Holt". Retrieved 2010-02-25.

- ^ "HOLT CAT – Texas Caterpillar Dealer Equipment Sales and Service". 2007. Archived from the original on 2007-04-19. Retrieved 2010-02-24.

- ^ "British 'Tanks' of American Type; Officer of Holt Manufacturing Co. Says England Bought 1,000 Tractors Here". The New York Times. 1916-09-16. p. 1.

- ^ Jay P. Pederson, editor. (2004). "Caterpillar Inc: Roots in Late 19th-Century Endeavors of Best and Holt". International Directory of Company Histories. Vol. 63. Farmington Hills, Michigan: St. James Press. ISBN 1-55862-508-9.

{{cite book}}:|author=has generic name (help) - ^ a b c "Holt Caterpillar". Archived from the original on 2009-12-04. Retrieved 2010-02-27.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ a b c d Swinton, Ernest (1972). Eyewitness. Ayer Publishing. ISBN 978-0-405-04594-3.

- ^ a b Venzon, Anne Cipriano (1999). The United States in the First World War. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 978-0-8153-3353-1.

- ^ a b c Dowling, Timothy C. (2005). Personal perspectives. Abc-Clio. ISBN 978-1-85109-565-0.

- ^ Vin Rouge, Vin Blanc, Beaucoup Vin, the American Expeditionary Force in WWI by Van Lee p.162 [1]

- ^ a b c d e f g Harris, J. P. (1995). Men, Ideas, and Tanks. Manchester University Press. ISBN 978-0-7190-4814-2.

- ^ Fletcher, David British Mark I Tank 1916 New Vanguard No. 100 Osprey Publishing 2004, p.12

- ^ Joseph Brinker (1918). "Now Comes the Cargo-Carrying Tank". Popular Science. Vol. 93, no. July. pp. 58–60.

- ^ Stern, A.G. Tanks 1914–1918; The Log Book of a Pioneer. Hodder & Stoughton, 1919

- ^ Over My Shoulder; The Autobiography of Major-General Sir Ernest D. Swinton. 1951

- ^ Tanks 1914–1918; The Log Book of a Pioneer. Hodder & Stoughton, 1919, et al.

- ^ Svirin, Mikhail (2009). Танковая мощь СССР (in Russian). Moscow: Yauza, Eksmo. pp. 15–17. ISBN 978-5-699-31700-4.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|trans_title=ignored (|trans-title=suggested) (help) - ^ Kholyavsky, Gennady (1998). Энциклопедия танков (in Russian). Minsk: Kharvest. p. 25. ISBN 985-13-8603-0.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|trans_title=ignored (|trans-title=suggested) (help) - ^ Tucker (2004), pp. 24-25

- ^ Tucker, Spencer (2005). World War I: Encyclopedia. Priscilla Mary Roberts. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 1-85109-420-2.

Bibliography

This article includes a list of general references, but it lacks sufficient corresponding inline citations. (September 2009) |

- Dwyer, Gray E. (9 August 1924). "Story of the Tanks; De Mole's Travelling Caterpillar Fort; Remarkable Letter From Perth in 1914". The Argus. p. 6, col. A. Retrieved 2010-04-03.

- Macksey and John H. Batchelor, Kenneth (1970). Tank: A History of the Armoured Fighting Vehicle. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons.

- Zaloga and James Grandsen, Steven J. (1984). Soviet Tanks and Combat Vehicles of World War Two. London: Arms and Armour Press. ISBN 0-85368-606-8.

- Tucker, Spencer (2005). World War I: Encyclopedia. Priscilla Mary Roberts. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 1-85109-420-2.

- Gudmundsson, Bruce I. (2004). On Armor. Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 0-275-95019-0.

- Gougaud, Alain (1987). L'Aube de la Gloire, Les Autos-Mitrailleuses et les Chars Français pendant la Grande Guerre. Musée des Blindés, ISBN 2-904255-02-8.

- Harris, J. P. (1995). Men, Ideas and Tanks: British Military Thought and Armoured Forces, 1903–39. Manchester: Manchester University Press. ISBN 978-0-7190-4814-2.

- Fletcher, David (1998). Armoured Fighting Vehicles of the World: AFVs of World War One. Duncan Crow and Maj. Gen. N. W. Duncan. Cannon Books. ISBN 1-899695-02-8.

External links

- Achtung Panzer – The history of tanks and people of the Panzertruppe.

- OnWar's Second World War Armour

- Peter Wollen: Tankishness London Review of Books Vol. 22 No. 22, 16 November 2000. (A review of the book Tank: The Progress of a Monstrous War Machine by Patrick Wright, covering in detail some topics like the development of the first tank in Britain or the influence of the tank in culture)