Insular Government of the Philippine Islands

Insular Government of the Philippine Islands | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1901–1935 | |||||||||

Location of Philippine Islands in Asia | |||||||||

| Status | U.S. territory | ||||||||

| Capital | Manila | ||||||||

| Common languages | Spanish, English, various local languages | ||||||||

| Governor-General | |||||||||

• 1901-04 | William H. Taft | ||||||||

• 1913-21 | Francis B. Harrison | ||||||||

• 1921-27 | Leonard Wood | ||||||||

• 1933-35 | Frank Murphy | ||||||||

| Legislature | Philippine Legislature | ||||||||

• Upper house | Philippine Commission (1901-16) Senate (1916-35) | ||||||||

• Lower house | Philippine Assembly (1907-16) House of Representatives (1916-35) | ||||||||

| Historical era | Twentieth century | ||||||||

• Established by the Spooner Amendment | 1 July 1901 | ||||||||

• Reorganized by the Philippine Organic Act | 1 July 1902 | ||||||||

• Reorganized by the Jones Law | 29 August 1916 | ||||||||

• Dissolved by the Tydings–McDuffie Act | 15 November[1][2][3][4] 1935 | ||||||||

| Area | |||||||||

| 1903 | 300,000 km2 (120,000 sq mi) | ||||||||

| 1918 | 300,000 km2 (120,000 sq mi) | ||||||||

| Population | |||||||||

• 1903 | 7,635,426 | ||||||||

• 1918 | 10,350,640 | ||||||||

| Currency | Philippine peso | ||||||||

| |||||||||

| |||||||||

The Insular Government of the Philippine Islands was a territorial government of the United States of America created in 1901 in what is now the Philippines.[5] The name reflects the fact that it was a civilian administration under the authority of the Bureau of Insular Affairs, in contrast to the military government that it replaced.

The government was originally organized in the newly acquired territory by the executive branch of the American government in order to replace military governance with civilian. Very quickly, in 1902, the United States Congress passed the Philippine Organic Act, which formally organized the Insular Government and served as its basic law, or organic act, similar to a constitution. This act provided for a Governor-General of the Philippines appointed by the President of the United States, as well as a bicameral Philippine Legislature with the appointed Philippine Commission as the upper house and a fully elected, fully Filipino elected lower house, the Philippine Assembly

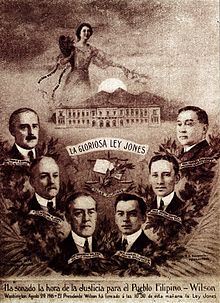

In 1916, Philippine Organic Act was replaced by the Jones Law, which ended the Philippine Commission and provided for both houses of the Philippine Legislature to be elected.

Finally, in 1935, the Insular Government was succeeded by the Commonwealth of the Philippines, still under the American government, as a previsionary step towards full independence in ten years. Delayed by World War II, the Philippines gained full sovereignty in 1946.

History

This section needs additional citations for verification. (September 2013) |

| History of the Philippines |

|---|

|

| Timeline |

|

|

The Insular Government evolved from the Taft Commission, or Second Philippine Commission, appointed on March 16, 1900. This group was headed by William Howard Taft, and was granted legislative powers by President William McKinley in September 1900. The commission created a judicial system, an educational system, a civil service, and a legal code. The legality of these actions was contested until the passage of the Spooner Amendment in 1901, which granted the U.S. President authority to govern the Philippines.[citation needed]

The Insular Government saw its mission as one of tutelage, preparing the Philippines for eventual independence.[6] On July 4, 1901, Taft was appointed "civil governor", with Military Governor Adna Chaffee retaining authority in disturbed areas. On July 4, 1902, the office of military governor was abolished, and Taft became the first U.S. Governor-General of the Philippines.[7]

The Philippine Organic Act disestablished the Roman Catholic Church in the Philippines as the state religion. In 1904, Taft negotiated the purchase of 390,000 acres of church property for $7.5 million.[8] This land was resold to tens of thousands of peasants, who received low-cost mortgages.[8]

Two years after the completion and publication of a census, a general election was conducted for the choice of delegates to a popular assembly. An elected Philippine Assembly was convened in 1907 as the lower house of a bicameral legislature, with the Philippine Commission as the upper house. Every year from 1907, the Philippine Assembly (and later the Philippine Legislature) passed resolutions expressing the Filipino desire for independence.

Philippine nationalists led by Manuel L. Quezon and Sergio Osmeña enthusiastically endorsed the draft Jones Bill of 1912, which provided for Philippine independence after eight years, but later changed their views, opting for a bill which focused less on time than on the conditions of independence. The nationalists demanded complete and absolute independence to be guaranteed by the United States, since they feared that too-rapid independence from American rule without such guarantees might cause the Philippines to fall into Japanese hands. The Jones Bill was rewritten and passed Congress in 1916 with a later date of independence.[9]

The law, officially the Philippine Autonomy Act but popularly known as the Jones Law, served as the new organic act for the Philippines. Its preamble stated that the eventual independence of the Philippines would be American policy, subject to the establishment of a stable government. The law maintained an appointed governor-general, but established a bicameral Philippine Legislature to replace the elected Philippine Assembly (lower house); it replaced the appointive Philippine Commission (upper house) with an elected senate.[10]

Filipinos suspended the independence campaign during the First World War and supported the United States and the Entente Powers against the German Empire. After the war they resumed their independence drive with great vigour.[11] On March 17, 1919, the Philippine Legislature passed a "Declaration of Purposes", which stated the inflexible desire of the Filipino people to be free and sovereign. A Commission of Independence was created to study ways and means of attaining liberation ideal. This commission recommended the sending of an independence mission to the United States.[12] The "Declaration of Purposes" referred to the Jones Law as a veritable pact, or covenant, between the American and Filipino peoples whereby the United States promised to recognize the independence of the Philippines as soon as a stable government should be established. American Governor-General of the Philippines Francis Burton Harrison had concurred in the report of the Philippine Legislature as to a stable government.

The Philippine Legislature funded an independence mission to the United States in 1919. The mission departed Manila on February 28 and met in America with and presented their case to Secretary of War Newton D. Baker.[13] U.S. President Woodrow Wilson, in his 1921 farewell message to Congress, certified that the Filipino people had performed the condition imposed on them as a prerequisite to independence, declaring that, this having been done, the duty of the U.S. is to grant Philippine independence.[14] The Republican Party then controlled Congress and the recommendation of the outgoing Democratic president was not heeded.[13]

After the first independence mission, public funding of such missions was ruled illegal. Subsequent independence missions in 1922, 1923, 1930, 1931 1932, and two missions in 1933 were funded by voluntary contributions. Numerous independence bills were submitted to the U.S. Congress, which passed the Hare–Hawes–Cutting Bill on December 30, 1932. U.S. President Herbert Hoover vetoed the bill on January 13, 1933. Congress overrode the veto on January 17, and the Hare–Hawes–Cutting Act became U.S. law. The law promised Philippine independence after 10 years, but reserved several military and naval bases for the United States, as well as imposing tariffs and quotas on Philippine exports. The law also required the Philippine Senate to ratify the law. Quezon urged the Philippine Senate to reject the bill, which it did. Quezon himself led the twelfth independence mission to Washington to secure a better independence act. The result was the Tydings–McDuffie Act of 1934 which was very similar to the Hare–Hawes–Cutting Act except in minor details. The Tydings–McDuffie Act was ratified by the Philippine Senate. The law provided for the granting of Philippine independence by 1946.[15]

The Tydings–McDuffie Act provided for the drafting and guidelines of a constitution for a ten-year "transitional period" as the Commonwealth of the Philippines before the granting of Philippine independence. On May 5, 1934, the Philippines Legislature passed an act setting the election of convention delegates. Governor-General Frank Murphy designated July 10 as the election date, and the Convention held its inaugural session on July 30. The completed draft Constitution was approved by the Convention on February 8, 1935, approved by U.S. President Franklin Roosevelt on March 23, and ratified by popular vote on May 14. The first election under the new 1935 constitution was held on September 17, and on November 15, 1935 the Commonwealth was put into place.[16]

Governor-General

On July 4, 1901, executive authority over the islands was transferred to the president of the Philippine Commission, who had the title of "civil governor"–a position appointed by the President of the United States and approved by the United States Senate. For the first year a military governor, Adna Chaffee, ruled parts of the country still resisting American rule, concurrent with civil governor William Howard Taft.[17] Disagreements between the two were not uncommon.[18] The following year, on July 4, 1902, the civil governor became the sole executive authority of the islands.[19] Chaffee remained as Commander of the Philippine Division until September 30, 1902.[20]

The title was changed to "Governor-General" in 1905 by Act of Congress (Public 43 - February 6, 1905).[19]

On November 15, 1935, the Commonwealth government was inaugurated. The office of President of the Philippines was created to replace the Governor-General as Chief Executive, taking over many of the former's duties. The American Governor-General then became known as the High Commissioner of the Philippines.

Resident Commissioners of the Philippines

From the passage of the Philippine Organic Act until Philippine independence, first the Insular Government and then the Philippine Commonwealth was represented in the United States House of Representatives by two, and then one, Resident Commissioner of the Philippines. Similar to delegates and the Resident Commissioner of Puerto Rico, they were nonvoting members of Congress.

References

- ^ Timeline 1930–1939, St. Scholastica's College

- ^ Gin Ooi 2004, p. 387.

- ^ Zaide 1994, p. 319.

- ^ Roosevelt, Franklin D (November 14, 1935), Proclamation 2148 on the Establishment of the Commonwealth of the Philippines, The American Presidency Project, University of California at Santa Barbara,

This Proclamation shall be effective upon its promulgation at Manila, Philippine Islands, on November 15, 1935, by the Secretary of War of the United States of America, who is hereby designated as my representative for that purpose.

- ^ Chapter 10: Insular Government 1901-1935, Americans in the Philippines[unreliable source?]

- ^ Dolan & 1991-16

- ^ Ellis 2008, p. 2163

- ^ a b "American President A Reference Resource", Miller Center, University of Virginia

- ^ Wong Kwok Chu, "The Jones Bills 1912-16: A Reappraisal of Filipino Views on Independence", Journal of Southeast Asian Studies 1982 13(2): 252-269

- ^ Philippine Autonomy Act of 1916 (Jones Law)

- ^ Zaide 1994, p. 312 Ch.24

- ^ Zaide 1994, pp. 312–313 Ch.24

- ^ a b Zaide 1994, p. 313

- ^ Kalaw 1921, pp. M1 144–146

- ^ Zaide 1994, pp. 314–315 Ch.24

- ^ Zaide 1994, pp. 315–319 Ch.24

- ^ Elliott (1917), p. 4

- ^ Tanner (1901), p. 383

- ^ a b Elliott (1917), p. 509

- ^ Philippine Academy of Social Sciences (1967). Philippine social sciences and humanities review. pp. 40.

Bibliography

- Dolan, Ronald E., ed. (1991-16). "United States Rule". Philippines: A Country Study. Washington: GPO for the Library of Congress. ISBN 0-8444-0748-8.

{{cite book}}: Check date values in:|year=(help) - Elliott, Charles Burke (1917). The Philippines: To the End of the Commission Government, a Study in Tropical Democracy. The Bobbs-Merrill Company.

- Kalaw, Maximo M. (March 2007) [1921]. The Present Government of the Philippines. Read Books. ISBN 978-1-4067-4636-5.

- *Seekins, Donald M. (1993), "The First Phase of United States Rule, 1898-1935", in Dolan, Ronald E. (ed.), Philippines: A Country Study (4th ed.), Washington, D.C.: Federal Research Division, Library of Congress

- Zaide, Sonia M. (1994). The Philippines: A Unique Nation. All-Nations Publishing Co. ISBN 971-642-071-4.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)

Further reading

- Philippines. Civil Service Board (1906). Annual Report of the Philippine Civil Service Board to the Civil Governor of the Philippine Islands, Issue 5. Contributors United States. Philippine Commission (1900-1916), United States. Bureau of Insular Affairs. Bureau of Public Printing. ISBN 9715501680. Retrieved 24 April 2014.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)