Intersex people in history

| Intersex topics |

|---|

|

Intersex, in humans and other animals, describes variations in sex characteristics including chromosomes, gonads, sex hormones, or genitals that, according to the UN Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights, "do not fit typical binary notions of male or female bodies".[1][2] Intersex people were historically termed hermaphrodites, "congenital eunuchs",[3][4] or even congenitally "frigid".[5] Such terms have fallen out of favor, now considered to be misleading and stigmatizing.[6]

Intersex people have been treated in different ways by different cultures. Whether or not they were socially tolerated or accepted by any particular culture, the existence of intersex people was known to many ancient and pre-modern cultures and legal systems, and numerous historical accounts exist.

Ancient history

Pre-history

A Sumerian creation myth from more than 4,000 years ago has Ninmah, a mother goddess, fashioning humanity out of clay.[7] She boasts that she will determine the fate – good or bad – for all she fashions:

Enki answered Ninmah: "I will counterbalance whatever fate – good or bad – you happen to decide.

Ninmah took clay from the top of the abzu [ab: water; zu: far] in her hand and she fashioned from it first a man who could not bend his outstretched weak hands. Enki looked at the man who cannot bend his outstretched weak hands, and decreed his fate: he appointed him as a servant of the king. (Three men and one woman with atypical biology are formed and Enki gives each of them various forms of status to ensure respect for their uniqueness)

...Sixth, she fashioned one with neither penis nor vagina on its body. Enki looked at the one with neither penis nor vagina on its body and gave it the name Nibru (eunuch(?)), and decreed as its fate to stand before the king.[7]

In traditional Jewish culture, intersex individuals were either androgynos or tumtum and took on different gender roles, sometimes conforming to men's, sometimes to women's.

Ancient Greece

According to DeVun, a "traditional Hippocratic/Galenic model of sexual difference – popularized by the late antique physician Galen and the ascendant theory for much of the Middle Ages – viewed sex as a spectrum that encompassed masculine men, feminine women, and many shades in between, including hermaphrodites, a perfect balance of male and female".[8] DeVun contrasts this with an Artistotelian view of intersex, which argued that "hermaphrodites were not an intermediate sex but a case of doubled or superfluous genitals", and this later influenced Aquinas.[8]

In the mythological tradition, Hermaphroditus was a beautiful youth who was the son of Hermes (Roman Mercury) and Aphrodite (Venus).[9] Ovid wrote the most influential narrative[10] of how Hermaphroditus became androgynous, emphasizing that although the handsome youth was on the cusp of sexual adulthood, he rejected love as Narcissus had, and likewise at the site of a reflective pool.[11] There the water nymph Salmacis saw and desired him. He spurned her, and she pretended to withdraw until, thinking himself alone, he undressed to bathe in her waters. She then flung herself upon him, and prayed that they might never be parted. The gods granted this request, and thereafter the body of Hermaphroditus contained both male and female. As a result, men who drank from the waters of the spring Salmacis supposedly "grew soft with the vice of impudicitia".[12] The myth of Hylas, the young companion of Hercules who was abducted by water nymphs, shares with Hermaphroditus and Narcissus the theme of the dangers that face the beautiful adolescent male as he transitions to adult masculinity, with varying outcomes for each.[13]

Ancient Rome

Pliny notes that "there are even those who are born of both sexes, whom we call hermaphrodites, at one time androgyni" (andr-, "man," and gyn-, "woman", from the Greek).[14] However, the era also saw a historical account of a congenital eunuch.[15]

The Sicilian historian Diodorus (latter 1st-century BC) wrote of "hermaphroditus" in the first century BCE:

Hermaphroditus, as he has been called, who was born of Hermes and Aphrodite and received a name which is a combination of those of both his parents. Some say that this Hermaphroditus is a god and appears at certain times among men, and that he is born with a physical body which is a combination of that of a man and that of a woman, in that he has a body which is beautiful and delicate like that of a woman, but has the masculine quality and vigour of man. But there are some who declare that such creatures of two sexes are monstrosities, and coming rarely into the world as they do they have the quality of presaging the future, sometimes for evil and sometimes for good.[16]

Isidore of Seville (c. 560–636) described a hermaphrodite fancifully as those who "have the right breast of a man and the left of a woman, and after coitus in turn can both sire and bear children."[17] Under Roman law, as many others, a hermaphrodite had to be classed as either male or female.[18] Roscoe states that the hermaphrodite represented a "violation of social boundaries, especially those as fundamental to daily life as male and female."[19]

In traditional Roman religion, a hermaphroditic birth was a kind of prodigium, an occurrence that signalled a disturbance of the pax deorum, Rome's treaty with the gods.[20] But Pliny observed that while hermaphrodites were once considered portents, in his day they had become objects of delight (deliciae) who were trafficked in an exclusive slave market.[21] According to Clarke, depictions of Hermaphroditus were very popular among the Romans:

Artistic representations of Hermaphroditus bring to the fore the ambiguities in sexual differences between women and men as well as the ambiguities in all sexual acts. ... (A)rtists always treat Hermaphroditus in terms of the viewer finding out his/her actual sexual identity. ... Hermaphroditus is a highly sophisticated representation, invading the boundaries between the sexes that seem so clear in classical thought and representation.[22]

In c.400, Augustine wrote in The Literal Meaning of Genesis that humans were created in two sexes, despite "as happens in some births, in the case of what we call androgynes".[8]

Historical accounts of intersex people include the sophist and philosopher Favorinus, described as a eunuch (εὐνοῦχος) by birth.[15][23] Mason and others thus describe Favorinus as having an intersex trait.[3][24][25]

A broad sense of the term "eunuch" is reflected in the compendium of ancient Roman laws collected by Justinian I in the 6th century known as the Digest or Pandects. Those texts distinguish between the general category of eunuchs (spadones, denoting "one who has no generative power, an impotent person, whether by nature or by castration",[26] D 50.16.128) and the more specific subset of castrati (castrated males, physically incapable of procreation). Eunuchs (spadones) sold in the slave markets were deemed by the jurist Ulpian to be "not defective or diseased, but healthy", because they were anatomically able to procreate just like monorchids (D 21.1.6.2). On the other hand, as Julius Paulus pointed out, "if someone is a eunuch in such a way that he is missing a necessary part of his body" (D 21.1.7), then he would be deemed diseased. In these Roman legal texts, spadones (eunuchs) are eligible to marry women (D 23.3.39.1), institute posthumous heirs (D 28.2.6), and adopt children (Institutions of Justinian 1.11.9), unless they are castrati.

Ancient Tamil

The Tirumantiram Tirumular recorded the relationship between Intersex people and Shiva.[27][further explanation needed]

Ancient India

Ardhanarishvara, an androgynous composite form of male deity Shiva and female deity Parvati, originated in Kushan culture as far back as the first century CE.[28] A statue depicting Ardhanarishvara is included in India's Meenkashi Temple; this statue clearly shows both male and female bodily elements.[29]

Middle Ages

In Abnormal (Les anormaux), Michel Foucault suggested it is likely that, "from the Middle Ages to the sixteenth century ... hermaphrodites were considered to be monsters and were executed, burnt at the stake and their ashes thrown to the winds."[30]

However, Christof Rolker disputes this, arguing that "Contrary to what has been claimed, there is no evidence for hermaphrodites being persecuted in the Middle Ages, and the learned laws did certainly not provide any basis for such persecution".[31] Canon Law sources provide evidence of alternative perspectives, based upon prevailing visual indications and the performance of gendered roles.[32] The 12th-century Decretum Gratiani states that "Whether an hermaphrodite may witness a testament, depends on which sex prevails" ("Hermafroditus an ad testamentum adhiberi possit, qualitas sexus incalescentis ostendit.").[33][34]

In the late twelfth century, the canon lawyer Huguccio stated that, "If someone has a beard, and always wishes to act like a man (excercere virilia) and not like a female, and always wishes to keep company with men and not with women, it is a sign that the male sex prevails in him and then he is able to be a witness, where a woman is not allowed".[35] Concerning the ordination of 'hermaphrodites', Huguccio concluded: "If therefore the person is drawn to the feminine more than the male, the person does not receive the order. If the reverse, the person is able to receive but ought not to be ordained on account of deformity and monstrosity."[35]

Henry de Bracton's De Legibus et Consuetudinibus Angliae ("On the Laws and Customs of England"), c. 1235,[36] classifies mankind as "male, female, or hermaphrodite",[37] and "A hermaphrodite is classed with male or female according to the predominance of the sexual organs."[38]

The thirteenth-century canon lawyer Henry of Segusio argued that a "perfect hermaphrodite" where no sex prevailed should choose their legal gender under oath.[39][31]

Early Modern Period

The 17th-century English jurist and judge Edward Coke (Lord Coke), wrote in his Institutes of the Lawes of England on laws of succession stating, "Every heire is either a male, a female, or an hermaphrodite, that is both male and female. And an hermaphrodite (which is also called Androgynus) shall be heire, either as male or female, according to that kind of sexe which doth prevaile."[40][41] The Institutes are widely held to be a foundation of common law.

A few historical accounts of intersex people exist due primarily to the discovery of relevant legal records, including those of Thomas(ine) Hall (17th-century USA), Eleno de Céspedes, a 16th-century intersex person in Spain Template:Es, and Fernanda Fernández (18th-century Spain).

In a court case, heard at the Castellania in 1774 during the Order of St. John in Malta, 17-year-old Rosa Mifsud from Luqa, later described in the British Medical Journal as a pseudo-hermaphrodite, petitioned for a change in sex classification from female.[42][43] Two clinicians were appointed by the court to perform an examination. They found that "the male sex is the dominant one".[43] The examiners were the Physician-in-Chief and a senior surgeon, both working at the Sacra Infermeria.[43] The Grandmaster himself who took the final decision for Mifsud to wear only men clothes from then on.[42]

Mid Modern Period

During the Victorian era, medical authors introduced the terms "true hermaphrodite" for an individual who has both ovarian and testicular tissue, verified under a microscope, "male pseudo-hermaphrodite" for a person with testicular tissue, but either female or ambiguous sexual anatomy, and "female pseudo-hermaphrodite" for a person with ovarian tissue, but either male or ambiguous sexual anatomy.

Historical accounts including those of Vietnamese general Lê Văn Duyệt (18th/19th-century) who helped to unify Vietnam; Gottlieb Göttlich, a 19th-century German travelling medical case; and Levi Suydam, an intersex person in 19th-century USA whose capacity to vote in male-only elections was questioned.

The memoirs of 19th-century intersex Frenchwoman Herculine Barbin were published by Michel Foucault in 1980.[44] Her birthday is marked in Intersex Day of Remembrance on 8 November.

Contemporary Period

The term intersexuality was coined by Richard Goldschmidt in the 1917 paper Intersexuality and the endocrine aspect of sex.[45][46][47] The first suggestion to replace the term 'hermaphrodite' with 'intersex' came from British specialist Cawadias in the 1940s.[48] This suggestion was taken up by specialists in the UK during the 1960s.[49][50] Historical accounts from the early twentieth century include that of Australian Florrie Cox, whose marriage was annulled due to "malformation frigidity".[5]

Since the rise of modern medical science in Western societies, some intersex people with ambiguous external genitalia have had their genitalia surgically modified to resemble either female or male genitals. Surgeons pinpointed intersex babies as a "social emergency" once they were born.[51] The parents of the intersex babies were not content about the situation. Psychologists, sexologists, and researchers frequently still believe that it is better for a baby's genitalia to be changed when they were younger than when they were a mature adult. These scientists believe that early intervention helped avoid gender identity confusion.[52] This was called the 'Optimal Gender Policy', and it was initially developed in the 1950s by John Money.[53] Money and others controversially believed that children were more likely to develop a gender identity that matched sex of rearing than might be determined by chromosomes, gonads, or hormones.[54] The primary goal of assignment was to choose the sex that would lead to the least inconsistency between external anatomy and assigned psyche (gender identity).

Since advances in surgery have made it possible for intersex conditions to be concealed, many people are not aware of how frequently intersex conditions arise in human beings or that they occur at all.[55] Dialog between what were once antagonistic groups of activists and clinicians has led to only slight changes in medical policies and how intersex patients and their families are treated in some locations.[56] Numerous civil society organizations and human rights institutions now call for an end to unnecessary "normalizing" interventions.

The first public demonstration by intersex people took place in Boston on October 26, 1996, outside the venue in Boston where the American Academy of Pediatrics was holding its annual conference.[57] The group demonstrated against "normalizing" treatments, and carried a sign saying "Hermaphrodites With Attitude".[58] The event is now commemorated by Intersex Awareness Day.[59]

In 2011, Christiane Völling became the first intersex person known to have successfully sued for damages in a case brought for non-consensual surgical intervention.[60] In April 2015, Malta became the first country to outlaw non-consensual medical interventions to modify sex anatomy, including that of intersex people.[61][62]

Timeline

| Intersex topics |

|---|

|

The following is a timeline of intersex history.

Timeline

<onlyinclude>

Pre-history

- Sumerian creation myths, 4000 years ago, include the fashioning of a body with atypical sex characteristics.[63]

Antiquity

- Hippocrates and Galen view sex as a spectrum between men and women, with "many shades in between, including hermaphrodites, a perfect balance of male and female".[8]

- Aristotle view hermaphrodites as having "doubled or superfluous genitals".[8]

2nd century BCE

- Callon of Epidaurus undergoes surgery on ambiguous genitalia, described by Diodorus Siculus.[64]

- Diophantus of Abae socially transitions and joins the army of Alexander Balas.[65]

1st century BCE

- Diodorus Siculus describes the god Hermaphroditus, "born of Hermes and Aphrodite", as having "a physical body which is a combination of that of a man and that of a woman"; he also reports that such children born with such traits are seen as prodigies, able to foretell future events.[66]

43 BCE – 17/18 CE

- Ovid describes the birth of Hermaphroditus.[67]

23–79 CE

- Pliny the Elder describes "those who are born of both sex, whom we call hermaphrodites, at one time androgyni" (andr-, "man", and gyn-, "woman", from the Greek).[68]

c. 80–160 CE

- Sophist philosopher Favorinus of Arelate is described as being a eunuch (εὐνοῦχος) by birth.[15][69] Mason and others describe Favorinus as having an intersex trait.[3]

Medieval period

c. 400 CE

- Augustine writes in The Literal Meaning of Genesis that humans were created in two sexes, despite "as happens in some births, in the case of what we call androgynes".[8]

c. 940 CE

- Hywel the Good's laws include a definition on the rights of hermaphrodites.[70]

12th century

- According to the canon law Decretum Gratiani, "Whether an hermaphrodite may witness a testament, depends on which sex prevails" (Hermafroditus an ad testamentum adhiberi possit, qualitas sexus incalescentis ostendit).[71][72]

- Peter Cantor, a French Roman Catholic theologian, when writing about sodomy in the De vitio sodomitico writes "the church allows the hermaphrodite to use the organ by which s/he is most aroused. But should s/he fail with one organ the use of the other can never be permitted and s/he must remain perpetually celibate to avoid any similarity to the role inversion of sodomy, which is detested by God."[73]

1157

- In his Chronicle, or History of the Two Cities, Otto of Friesing described hermaphrodites as "a mistake of nature", "grouped together with other supposed defects of the body, such as short stature, dark 'Ethiopian' skin, and lameness".[8]

1188

- Gerald of Wales in Topography of Ireland states "Also, within our time, a woman was seen attending the court in Connaught, who partook of the nature of both sexes, and was a hermaphrodite."[70]

13th century

- Canon lawyer Henry of Segusio argues that a "perfect hermaphrodite" where no sex prevailed should choose their legal gender under oath.[74][75]

- Henry de Bracton's De Legibus et Consuetudinibus Angliae ("On the Laws and Customs of England", c. 1235)[76] classifies mankind as "male, female, or hermaphrodite",[77] and a "hermaphrodite is classed with male or female according to the predominance of the sexual organs".[78]

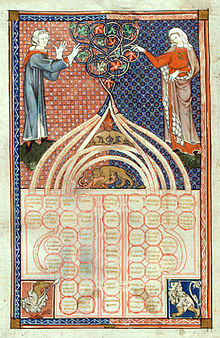

- The Hereford Mappa Mundi (c. 1300) includes a hermaphrodite, outside the borders of the world known to its makers.[79][80]

17th century

- English jurist and judge Edward Coke (Lord Coke) writes in his Institutes of the Lawes of England (1628–1644) on laws of succession: "Every heire is either a male, a female, or an hermaphrodite, that is both male and female. And an hermaphrodite (which is also called Androgynus) shall be heire, either as male or female, according to that kind of sexe which doth prevaile."[81][82] The Institutes are widely held to be a foundation of common law.

- 17th-century historical accounts include Eleno de Céspedes, in Spain.

- Thomas(ine) Hall (born c. 1603) in the United States, is ruled to have a "dual-nature" gender by colonial Virginia governor John Pott.

18th century

1755 – after 1792

- Spanish nun Fernanda Fernández is found to have an intersex trait and subsequently reclassified male.

1763/1764 – 1832

- Vietnamese general Lê Văn Duyệt helps to unify Vietnam.

1774

- 17-year-old Rosa Mifsud appears before a Maltese court after petitioning for a change in sex classification from female.[42][43] Two clinicians perform an examination and found that "the male sex is the dominant one".[43] The petition is appealed and granted.[42]

1792

- Anglo-Welsh philologist William Jones publishes an English translation of Al Sirájiyyah: The Mohammedan Law of Inheritance which details inheritance rights for hermaphrodites in Islam.[83]

1794

- The General State Laws for the Prussian States (Allgemeines Landrecht für die Preußischen Staaten) grants hermaphrodites the right to choose their sex at the age of 18, if the sex of rearing proves to be wrong.[84] It remains in force until 1900 when the Bürgerliches Gesetzbuch becomes effective across the German Empire.

c. 1798

- German intersex man Gottlieb Göttlich becomes famous as a travelling medical case.

19th century

1843

- Levi Suydam is an intersex person in Connecticut whose capacity to vote in male-only elections is questioned in 1843.[85]

1838–1868

- Herculine Barbin writes memoirs that are later published by Michel Foucault. Barbin was reassigned male against her wishes after clinical and legal examination.[86] Her birthday is marked in Intersex Day of Remembrance on 8 November.

1851

- The Welshman newspaper publishes an account of an intersex child on 7 November.[87]

- During the Victorian era, medical authors introduce the terms "true hermaphrodite" for an individual who has both ovarian and testicular tissue, verified under a microscope; "male pseudo-hermaphrodite" for a person with testicular tissue, but either female or ambiguous sexual anatomy; and "female pseudo-hermaphrodite" for a person with ovarian tissue, but either male or ambiguous sexual anatomy.

20th century

1906

- The Cambrian newspaper in Wales publishes an article on the death in Cardiff of an intersex child who, at post-mortem examination, was determined to be a girl.[88]

1908

- Polish gynecologist Franciszek Ludwik Neugebauer publishes a compendium with more than 750 pages of case studies, often with photos, covering the preceding 20 years.[89] This includes surgery performed at the beginning of the 20th century by Emil Zuckerkandl in Vienna.

1915

- The terms 'intersex' for the individual and 'intersexuality' for the phenomenon are coined in the German language by endocrinologist Richard Goldschmidt[90] after studies on gypsy moths. One year later, Goldschmidt uses the term to describe pseudohermaphroditism in humans.[91][92]

1923

- The term 'intersex' is introduced as the (contested) medical diagnosis Weib intersexuellen Typus ("intersex type woman") by Austrian gynecologist and obstetrician Paul Mathes[93] His book is published after his death, in 1924.[94]

1930

- By 1930, the term 'intersex' had already been widely used in medicine in Germany as a new term for Scheinzwitter (pseudohermaphrodite), and doctors reported numerous different procedures of intersex surgery.[95]

1932

- The German gynecologist and obstetrician Hans Naujoks performs what is described as the first complete and comprehensive intersex surgery and hormone treatment on a patient with both ovarian and testicular tissue, at the University of Marburg. The female patient is described as fully functional after surgery and, starting in 1934, spontaneously menstruates.[96]

1936

- The geneticist and leading German race theorist Fritz Lenz calls for more intersex research, especially on twins.[97]

1943

- Hugo Höllenreiner, an ethnic Sinti detainee in Auschwitz concentration camp, is genitally injured at the age of 9 during medical experiments carried out by Josef Mengele, acts which constitute war crimes. Höllenreiner testifies[when?] that he was one of Mengele's many candidates for forced sex change but did not receive full surgery.[98]

- The first suggestion to replace the term 'hermaphrodite' with 'intersex', in medicine, comes from British physician A. P. Cawadias in 1943.[48] This is taken up by other physicians in the United Kingdom during the 1960s.[99][100]

1944

- The first intersex surgery of a child is performed at the Children's Hospital of the University of Zurich (Kinderspital Zürich). The girl, suffering from congenital adrenal hyperplasia, has her clitoris amputated at the age of seven. She receives hormones in 1951. Between 1944 and 1947, three girls have their clitorises amputated.[101]

1950

- In July, the first mandatory sex verification tests in sports are issued by the International Association of Athletics Federations (IAAF) for woman athletes. All athletes are tested in their own countries.[102]

1952

- John Money is awarded a PhD by Harvard University, entitled Hermaphroditism: An Inquiry into the Nature of a Human Paradox.

1966

- The botched circumcision of David Reimer is followed by sex reassignment surgery in line with theories on optimal gender and gender identity formation by John Money. The case of David Reimer became known as the "John/Joan case" and it does not support early interventions on the bodies of infants who cannot consent.

1968

- Chromosomal sex verification testing in sport is introduced by the International Olympic Committee at the Mexico City Olympics.[103]

1979

- The Family Court of Australia annulls the marriage of an intersex man who was "born a male and had been reared as a male" and subjected to "normalizing" medical interventions, on the basis that he is an hermaphrodite.[104]

1980

- Former Polish Olympic track athlete Stanisława Walasiewicz (Stella Walsh) is killed during an armed robbery in a parking lot in Cleveland, Ohio, on 4 December 1980.[105][106] She is found to have intersex traits.[107]

1985

- The Androgen Insensitivity Syndrome Support Group Australia (AISSGA) is founded, thought to be the first intersex civil society organization.[108][109]

1986

- Spanish hurdler Maria José Martínez-Patiño is dismissed from competing after she fails a chromosomal test.[110]

1992

- The IAAF ceases sex screening for all athletes,[111] but retains the option of assessing the sex of participants.

1993

- The Intersex Society of North America (ISNA) is founded by Cheryl Chase and others. Chase announces the organization in a letter to The Sciences.[112] ISNA remains active until 2008.

1996

- The first public demonstration by intersex people, in Boston on October 26. Morgan Holmes, Max Beck and members of the direct action groups Hermaphrodites With Attitude! and The Transexual Menace [sic] demonstrate outside the hotel complex in Boston where the American Academy of Pediatrics is holding its annual conference.[57][113] The event is now commemorated by Intersex Awareness Day.[59]

1997

- Milton Diamond and Keith Sigmundson publish a paper discrediting John Money and his optimal gender model, after tracking down David Reimer.[114][115]

1999

- In Sentencia SU-337/99 and then Sentencia T-551/99, the Constitutional Court of Colombia restricts medical interventions on intersex children aged over five years.[116]

- The term endosex is coined as an opposite or antonym to the term intersex, by Heike Bödeker in Germany.[117]

21st century

2001

- Indian athlete and swimmer Pratima Gaonkar commits suicide after disclosure and public commentary on a failed sex verification test.[118][119][120]

2003

- Australian Alex MacFarlane is believed to be the first person in Australia to obtain a birth certificate recording sex as indeterminate, and the first Australian passport with an 'X' sex marker.[121][122]

2004

- Intersex Awareness Day is first marked on 26 October.[59]

2005

- In South Africa, the Judicial Matters Amendment Act, 2005 (Act 22 of 2005) amends the Promotion of Equality and Prevention of Unfair Discrimination Act, 2000 (Act 4 of 2000) to include intersex within its definition of sex, due in part to the work of Sally Gross.[123]

- The Human Rights Commission of the City and County of San Francisco publishes the first report on the treatment of intersex people by a human rights institution, entitled A Human Rights Investigation into the Medical "Normalization" of Intersex People.[124]

2006

- Publication of the Yogyakarta Principles on the Application of International Human Rights Law in relation to Sexual Orientation and Gender Identity includes Principle 18 on Protection from Medical Abuses, including "all necessary legislative, administrative and other measures to ensure that no child's body is irreversibly altered by medical procedures in an attempt to impose a gender identity without the full, free and informed consent of the child". Intersex and transgender activist Mauro Cabral is the only intersex signatory to the Principles.

- The medical Consensus statement on management of intersex disorders is published, changing clinical language from "intersex" to "disorders of sex development".[125]

- Indian middle-distance runner Santhi Soundarajan wins the silver medal in 800 m at the 2006 Asian Games in Doha, Qatar, then fails a sex verification test and is stripped of her medal.

2009

- South African middle-distance runner Caster Semenya wins the 800 meters at the 2009 World Championships in Athletics in Berlin. After her victory at the 2009 World Championships, it is announced that she has been subjected to sex verification testing, bringing intersex issues to the public eye. On 6 July 2010, the IAAF confirmed that Semenya is cleared to continue competing. The results of the testing are never officially released for privacy reasons and her personal status is unknown.[126]

2010

- In the Kenyan High Court case of Richard Muasya v. the Hon. Attorney General, Muasya is convicted of robbery with violence. The case examines whether or not he has suffered discrimination as a result of being born intersex. He is found to have been subjected to inhuman and degrading treatment while in prison. The Court also determines that he has not suffered from lack of identification documents, but is responsible for registering his own birth, following a failure to do so at the time of his birth.[127]

2011

- Christiane Völling becomes the first intersex person known to have successfully sued for damages in a case brought for non-consensual surgical intervention.[60]

- Tony Briffa, believed to be the world's first intersex mayor, is elected in the City of Hobsons Bay in the suburbs of Melbourne, Australia, at the end of November.[128]

- The first International Intersex Forum is held, in Brussels.

2012

- The Swiss National Advisory Commission Biomedical Ethics publishes a report on the management of differences of sex development.[129]

- On 14 November 2012, the Supreme Court of Chile orders Maule Health Service to pay compensation of 100 million pesos for moral and psychological damages caused to a child, Benjamín, and another 5 million for each of his parents. Born with ambiguous genitalia, doctors surgically removed his testicles without his parents' informed consent, following which he was raised initially as a girl until the age of 10 when tests revealed that he was male.[130][131] (See also Intersex rights in Chile.)

2013

- On 1 February, Juan E. Méndez, the UN Special Rapporteur on torture and other cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment, issues a statement condemning non-consensual surgical intervention on intersex people.[132][133]

- Patrick Fénichel, Stéphane Bermon and other clinicians disclose that four elite female athletes from developing countries were subjected to partial clitoridectomies and gonadectomies (sterilization) after testosterone testing revealed that they had the intersex condition 5-alpha-reductase deficiency.[134][135]

- In June, Australia passes legislation protecting intersex people from discrimination on grounds of "intersex status".[136]

- In October, the Council of Europe adopts resolution 1952, Children's right to physical integrity.[137]

- Also in October, the Australian Senate becomes the first parliamentary body to publish an inquiry into the involuntary or coerced sterilization of intersex people, entitled Involuntary or coerced sterilisation of intersex people in Australia.[136]

- Intersex activists testify for the first time before the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights.[109]

- Germany passes a law requiring intersex infants who may not be classed as male or female to be assigned as "indeterminate". The move is criticized by civil society organizations and human rights institutions as not based around principles of self-determination.[138]

- In December, participants at the Third International Intersex Forum publish the Malta declaration.[139][140][141][142][143][144][145]

2014

- The High Court of Kenya orders the Kenyan government to issue a birth certificate to a five-year-old child born in 2009 with ambiguous genitalia.[146]

- The World Health Organization and other UN agencies publish a joint statement against coercive sterilization.[147]

2015

- Malta becomes the first country to outlaw non-consensual medical interventions to modify sex anatomy, including that of intersex people. In the same law, it also becomes the first jurisdiction to protect intersex and other people from discrimination on grounds of "sex characteristics".[61][62]

- The Commissioner for Human Rights of the Council of Europe calls for recognition of a right to not undergo sex affirmation interventions.[148]

- In July, policies on sex verification in sport excluding women with hyperandrogenism are suspended following the case of Dutee Chand v. Athletics Federation of India (AFI) & The International Association of Athletics Federations, in the Court of Arbitration for Sport.[149]

- Michaela Raab successfully sues doctors in Nuremberg, Germany who failed to properly advise her. Doctors stated that they "were only acting according to the norms of the time".[150] On 17 December 2015, the Nuremberg State Court rules that the University of Erlangen-Nuremberg Clinic must pay damages and compensation.[151]

- The Astraea Lesbian Foundation for Justice establishes the first Intersex Human Rights Fund, in an attempt to address resourcing issues.[152][153]

- The Ugandan Registration of Persons Act 2015 allows for the birth registration of a child born a "hermaphrodite", and for children's change of name and change of sex classification.[154][155] Many adult intersex persons are understood to be stateless due to historical difficulties in obtaining identification documents.[155][not specific enough to verify]

2016

- In January, the Ministry of Health of Chile orders the suspension of unnecessary normalization treatments for intersex children, including irreversible surgery, until they reach an age when they can make decisions on their own.[156][157] This is overturned in August 2016.

- In October, the United Nations, African Commission on Human and Peoples' Rights, Inter-American Commission on Human Rights, Council of Europe Commissioner for Human Rights, and other global experts on human rights and child rights call for an urgent end to violence and harmful practices on intersex children and adults.[158]

- In October, the United Nations Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights launches a website on intersex human rights entitled United Nations for Intersex Awareness.[159]

- Research suggests that there has been no reduction in the number of intersex medical interventions in Germany over the period since 2005.[160]

- Gopi Shankar Madurai becomes the first openly intersex and genderqueer person to contest in an Indian state assembly election for the state of Tamil Nadu. Later, they become the first openly intersex statutory authority[vague] in India.

2017

- The French Senate publishes a second parliamentary inquiry into the wellbeing and rights of intersex people.[161] On 17 March 2017, the president of the Republic, François Hollande, describes medical interventions to make the bodies of intersex children more typically male or female as increasingly considered to be mutilations.[162]

- In March 2017, representatives of Androgen Insensitivity Syndrome Support Group Australia, Intersex Trust Aotearoa New Zealand, and Organisation Intersex International Australia publish an Australian and Aotearoa/New Zealand consensus "Darlington Statement",[163] calling for legal reform, including the criminalization of deferrable intersex medical interventions on children, an end to legal classification of sex, and improved access to peer support.[163][164][165][166][167]

- Following a European conference in March, the Vienna Statement is published. It calls for an end to human rights violations, and recognition of rights to bodily integrity, physical autonomy and self-determination.[168]

- In April, the fourth International Intersex Forum is held in the Netherlands.

- In May, Amnesty International publishes a report condemning "non-emergency, invasive and irreversible medical treatment with harmful effects" on children born with variations of sex characteristics in Germany and Denmark.[169][170]

- In June, Joycelyn Elders, David Satcher, and Richard Carmona, three former Surgeons General of the United States, publish a paper calling for a rethink of early genital surgeries on children with intersex traits, stating "Those whose oath or conscience says 'do no harm' should heed the simple fact that, to date, research does not support the practice of cosmetic infant genitoplasty."[171][172][173]

- In July, Human Rights Watch and interACT publish a report on medically unnecessary surgeries on intersex children in the U.S., "I Want to Be Like Nature Made Me", based on interviews with intersex persons, families and physicians.[174]

- The U.S. legal case M. C. v. Aaronson is settled out of court.

- The Yogyakarta Principles plus 10 are published, applying international human rights law in relation to sex characteristics, in addition to sexual orientation, gender identity and gender expression. Intersex signatories include Mauro Cabral Grinspan, Morgan Carpenter and Kimberly Zieselman.

- In November, Betsy Driver becomes the first intersex person openly elected to public office in the United States.[175]

- In December, African intersex activists publish a statement setting out local demands.[176]

2018

- In February, Asian intersex activists publish the Statement of Intersex Asia and the Asian Intersex Forum, setting out local demands.[177]

- In April, Latin American and Caribbean intersex activists publish the San José de Costa Rica statement, defining local demands.[178]

- On 15 August, the German cabinet announce a law to create a new sex designation "diverse" in vital records for intersex people who cannot be clearly assigned either male or female at birth.[179] This complies with an Order of the Federal Constitutional Court.[180] LGBT activists say that the law would be failing to make this category available to non-intersex people, and failing to address concerns about medical interventions.[181]

- On 28 August, California becomes the first U.S. state to condemn nonconsensual surgeries on intersex children, in Resolution SCR-110.[182][183]

2019

- On 1 May, the Court of Arbitration for Sport rejects a challenge by Caster Semenya to IAAF rules requiring the medicalization of women with particular "differences of sex development", high testosterone and androgen sensitivity in sport, paving the way for the new rules to come into effect on 8 May 2019.[184] During the legal challenge by Semenya, the IAAF changes the regulations to exclude from the regulations high testosterone associated with XX sex chromosomes.[185] Semenya appeals the decision to the Federal Supreme Court of Switzerland.[186]

- In May 2019, more than 50 intersex-led organizations sign a multilingual joint statement condemning the introduction of "disorders of sex development" language into the International Classification of Diseases, stating that this causes "harm" and facilitates human rights violations, calling on the World Health Organization to publish clear policy to ensure that intersex medical interventions are "fully compatible with human rights norms".[187][188][189][190][191]

- In June 2019, a widely signed statement[192] from intersex groups and their allies condemns the positions on intersex issues of the text "'Male and Female He Created Them': Towards a Path of Dialogue on the Question of Gender Theory in Education"[193] by the Congregation for Catholic Education.

- On 22 April 2019, the Madras High Court (Madurai Bench) hands down a landmark judgment[194] and issues a direction to ban sex-selective surgeries on intersex infants based on the works of Gopi Shankar Madurai. On 13 August the Government of Tamil Nadu issues an order to ban sex reassignment surgery on babies and children in the state except in life-threatening situations.[195][196][197]

2020

- In July 2020, Lurie Children's Hospital becomes the first hospital in the United States to stop performing medically unnecessary cosmetic surgeries in intersex infants and publicly apologizes to those harmed by past surgeries.[198]

- In October 2020, Boston Children's Hospital announces that they will stop performing clitorplasties and vaginoplasties in intersex infants and will wait until the patient can meaningfully participate in conversations about risks and benefits of the procedure and give consent.[199]

See also

Footnotes

- ^ "Free & Equal Campaign Fact Sheet: Intersex" (PDF). United Nations Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights. 2015. Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 28 March 2016.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Domurat Dreger, Alice (2001). Hermaphrodites and the Medical Invention of Sex. USA: Harvard University Press. ISBN 0-674-00189-3.

- ^ a b c Mason, H.J., Favorinus’ Disorder: Reifenstein's Syndrome in Antiquity?, in Janus 66 (1978) 1–13. Cite error: The named reference "mason" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ Nguyễn Khắc Thuần (1998), Việt sử giai thoại (History of Vietnam's tales), vol. 8, Vietnam Education Publishing House, p. 55

- ^ a b Richardson, Ian D. (May 2012). God's Triangle. Preddon Lee Limited. ISBN 9780957140103.

- ^ Dreger, Alice D; Chase, Cheryl; Sousa, Aron; Gruppuso, Phillip A.; Frader, Joel (18 August 2005). ""Changing the Nomenclature/Taxonomy for Intersex: A Scientific and Clinical Rationale."" (PDF). Journal of Pediatric Endocrinology and Metabolism. Archived from the original (PDF) on 20 December 2016. Retrieved 27 July 2016.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ a b "The Electronic Text Corpus of Sumerian Literature". Archived from the original on 24 December 2008. Retrieved 9 December 2007.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ a b c d e f g DeVun, Leah (June 2018). "Heavenly hermaphrodites: sexual difference at the beginning and end of time". postmedieval. 9 (2): 132–146. doi:10.1057/s41280-018-0080-8. ISSN 2040-5960. Cite error: The named reference "devun-2018" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ Ovid, Metamorphoses 4.287–88.

- ^ Taylor, The Moral Mirror of Roman Art, p. 77; Clarke, Looking at Lovemaking, p. 49.

- ^ Taylor, The Moral Mirror of Roman Art, p. 78ff.

- ^ Paulus ex Festo 439L; Richlin, "Not before Homosexuality," p. 549.

- ^ Taylor, The Moral Mirror of Roman Art, p. 216, note 46.

- ^ Pliny, Natural History 7.34: gignuntur et utriusque sexus quos hermaphroditos vocamus, olim androgynos vocatos; Veronique Dasen, "Multiple Births in Graeco-Roman Antiquity," Oxford Journal of Archaeology 16.1 (1997), p. 61.

- ^ a b c Philostratus, VS 489

- ^ Diodorus Siculus (1935). Library of History (Book IV). Loeb Classical Library Volumes 303 and 340. C H Oldfather (trans.). Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. Archived from the original on 2008-09-27.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Isidore of Seville, Eytmologiae 11.3. 11.

- ^ Lynn E. Roller, "The Ideology of the Eunuch Priest," Gender & History 9.3 (1997), p. 558.

- ^ Roscoe, "Priests of the Goddess," p. 204.

- ^ Veit Rosenberger, "Republican nobiles: Controlling the Res Publica," in A Companion to Roman Religion (Blackwell, 2007), p. 295.

- ^ Plutarch, Moralia 520c; Dasen, "Multiple Births in Graeco-Roman Antiquity," p. 61.

- ^ Clarke, Looking at Lovemaking, pp. 54–55.

- ^ Swain, Simon, "Favorinus and Hadrian," in ZPE 79 (1989), 150-158

- ^ Horstmanshoff (2000) 103 n. 39

- ^ Eugenio Amato (intr., ed., comm.) and Yvette Julien (trans.), Favorinos d'Arles, Oeuvres I. Introduction générale - Témoignages - Discours aux Corinthiens - Sur la Fortune, Paris: Les Belles Lettres (2005).

- ^ "Charlton T. Lewis, Charles Short, A Latin Dictionary". Retrieved 21 October 2006.

- ^ Winter, Gopi Shankar (2014). Maraikkappatta Pakkangal: மறைக்கப்பட்ட பக்கங்கள். Srishti Madurai. ISBN 9781500380939. OCLC 703235508.

- ^ Swami., Parmeshwaranand, (2004). Encyclopaedia of the Śaivism (1st ed.). New Delhi: Sarup & Sons. ISBN 8176254274. OCLC 54930404.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: extra punctuation (link) CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Shankar, Gopi (March–April 2015). "The Many Genders of Old India". The Gay & Lesbian Review Worldwide. 22: 24–26 – via ProQuest.

- ^ Foucault, Michel (2003). Abnormal: Lectures at the Collège de France 1974-1975. Verso. p. 67.

- ^ a b Rolker, Christof (2014-01-01). "The two laws and the three sexes: ambiguous bodies in canon law and Roman law (12th to 16th centuries)". Zeitschrift der Savigny-Stiftung für Rechtsgeschichte: Kanonistische Abteilung. 100 (1). doi:10.7767/zrgka-2014-0108. ISSN 2304-4896. Retrieved 2018-09-09.

- ^ Rolker, Christof (2013). "Double sex, double pleasure? Hermaphrodites and the medieval laws". Leeds, England. Archived from the original on 2015-12-08. Retrieved 2016-08-27.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help); Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Decretum Gratiani, C. 4, q. 2 et 3, c. 3

- ^ "Decretum Gratiani (Kirchenrechtssammlung)". Bayerische StaatsBibliothek (Bavarian State Library). February 5, 2009. Archived from the original on December 20, 2016.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ a b Raming, Ida; Macy, Gary; Bernard J, Cook (2004). A History of Women and Ordination. Scarecrow Press. p. 113.

- ^ Henry de Bracton. (2009). In Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 17 March 2009, from Encyclopædia Britannica Online Archived 2009-03-24 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ de Bracton, Henry. On the Laws and Customs of England. Vol. 2 (Thorne ed.). p. 31. Archived from the original on 2016-10-29.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ de Bracton, Henry. On the Laws and Customs of England. Vol. 2 (Thorne ed.). p. 32. Archived from the original on 2016-10-29.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Henrici de Segusio, Cardinalis Hostiensis, Summa aurea, Venice 1574 here at col. 612.

- ^ E Coke, The First Part of the Institutes of the Laws of England, Institutes 8.a. (1st Am. Ed. 1812).

- ^ Greenberg, Julie (1999). "Defining Male and Female: Intersexuality and the Collision Between Law and Biology". Arizona Law Review. 41: 277–278. SSRN 896307.

- ^ a b c d Savona-Ventura, Charles (2015). Knight Hospitaller Medicine in Malta [1530–1798]. Lulu. p. 115. ISBN 132648222X. Archived from the original on 2017-02-06.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) Cite error: The named reference "ventura" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page). - ^ a b c d e Cassar, Paul (11 December 1954). "Change of Sex Sanctioned by a Maltese Law Court in the Eighteenth Century". British Medical Journal. 2 (4901). Malta University Press: 1413. PMC 2080334. PMID 13209141. Archived from the original (PDF) on 5 February 2017. Cite error: The named reference "cassar1954" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ Barbin, Herculine (1980). Herculine Barbin: Being the Recently Discovered Memoirs of a Nineteenth-century French Hermaphrodite. introd. Michel Foucault, trans. Richard McDougall. New York: Pantheon Books. ISBN 0-394-50821-1.

- ^ Goldschmidt, R. (1917), "Intersexuality and the endocrine aspect of sex", Endocrinology, 1 (4): 433–456, doi:10.1210/endo-1-4-433.

- ^ Hirschfeld, M. (1923) 'Die Intersexuelle Konstitution.' Jahrbuch fuer sexuelle Zwischenstufen, 23, 3–27.

- ^ Voss, Heinz-Juergen. "Sex In The Making - A Biological Account" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-06-01.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ a b Cawadias, A. P. (1943) Hermaphoditus the Human Intersex, London, Heinemann Medical Books Ltd. Cite error: The named reference "Cawadias, A. P. 1943" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ Armstrong, C. N. (1964) "Intersexuality in Man", IN ARMSTRONG, C. N. & MARSHALL, A. J. (Eds.) Intersexuality in Vertebrates Including Man, London, New York, Academic Press Ltd.

- ^ Dewhurst, S. J. & Gordon, R. R. (1969) The Intersexual Disorders, London, Baillière Tindall & Cassell.

- ^ Coran, Arnold G.; Polley, Theodore Z. (July 1991). "Surgical management of ambiguous genitalia in the infant and child". Journal of Pediatric Surgery. 26 (7): 812–820. doi:10.1016/0022-3468(91)90146-K. PMID 1895191.

- ^ Fausto-Sterling, Anne (2000). Sexing the Body: Gender Politics and the Construction of Sexuality. New York: Basic Books. ISBN 0-465-07713-7.

- ^ National Advisory Commission on Biomedical Ethics (November 2012). On the management of differences of sex development. Ethical issues relating to "intersexuality".Opinion No. 20/2012 (PDF). Berne, Switzerland. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2015-04-23.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help)CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Australian Senate; Community Affairs References Committee (October 2013). Involuntary or coerced sterilisation of intersex people in Australia. Canberra: Community Affairs References Committee. ISBN 9781742299174. Archived from the original on 2015-09-23.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Dreger, Alice Domurat (May 1998). ""Ambiguous Sex"--or Ambivalent Medicine?"". Hastings Center Report. 28 (3): 24–35.

- ^ Dreger, Alice (3 April 2015). "Malta Bans Surgery on Intersex Children". The Stranger SLOG. Archived from the original on 18 July 2015.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ a b Holmes, Morgan (17 October 2015). "When Max Beck and Morgan Holmes went to Boston". Intersex Day. Archived from the original on 20 October 2015. Retrieved 2015-10-24.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) Cite error: The named reference "holmes" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page). - ^ Beck, Max. "Hermaphrodites with Attitude Take to the Streets". Intersex Society of North America. Archived from the original on 2015-10-05. Retrieved 2015-10-24.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ a b c Driver, Betsy (14 October 2015). "The origins of Intersex Awareness Day". Intersex Day. Archived from the original on 20 October 2015. Retrieved 2015-10-24.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) Cite error: The named reference "driver" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page). - ^ a b International Commission of Jurists. "In re Völling, Regional Court Cologne, Germany (6 February 2008)". Archived from the original on 5 January 2016. Retrieved 27 December 2015.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) Cite error: The named reference "icj1" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page). - ^ a b Reuters (1 April 2015). "Surgery and Sterilization Scrapped in Malta's Benchmark LGBTI Law". The New York Times.

{{cite news}}:|last=has generic name (help) Cite error: The named reference "nyt-2015" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page). - ^ a b "Malta passes law outlawing forced surgical intervention on intersex minors". Star Observer. 2 April 2015. Archived from the original on 14 August 2015.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) Cite error: The named reference "star-2015" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page). - ^ "The Electronic Text Corpus of Sumerian Literature". Archived from the original on 24 December 2008. Retrieved 9 December 2007.

- ^ Markantes, Georgios; Deligeoroglou, Efthimios; Armeni, Anastasia; Vasileiou, Vasiliki; Damoulari, Christina; Mandrapilia, Angelina; Kosmopoulou, Fotini; Keramisanou, Varvara; Georgakopoulou, Danai; Creatsas, George; Georgopoulos, Neoklis (2015-07-10). "Callo: The first known case of ambiguous genitalia to be surgically repaired in the history of Medicine, described by Diodorus Siculus". Hormones. 14 (3): 459–461. doi:10.14310/horm.2002.1608. PMID 26188239.

- ^ Petersen, Jay Kyle (2020-12-21). A Comprehensive Guide to Intersex. Jessica Kingsley. pp. 209–210. ISBN 978-1-78592-632-7.

- ^ Diodorus Siculus (1935). Library of History (Book IV). Loeb Classical Library Volumes 303 and 340. Translated by Oldfather, C. H. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press. Archived from the original on 2008-09-27.

- ^ Ovid, Metamorphoses 4.287–88.

- ^ Pliny, Natural History 7.34: gignuntur et utriusque sexus quos hermaphroditos vocamus, olim androgynos vocatos; Veronique Dasen, "Multiple Births in Graeco-Roman Antiquity", Oxford Journal of Archaeology 16.1 (1997), p. 61.

- ^ Swain, Simon (1989). "Favorinus and Hadrian". ZPE. 79: 150–158.

- ^ a b Shopland, Norena (2017), Forbidden Lives: LGBT Stories from Wales, Seren Books

- ^ Decretum Gratiani, C. 4, q. 2 et 3, c. 3

- ^ "Decretum Gratiani (Kirchenrechtssammlung)". Bayerische StaatsBibliothek (Bavarian State Library). February 5, 2009. Archived from the original on December 20, 2016.

- ^ Preves, Sharon E. (2003). Intersex and Identity: The Contested Self. New Jersey: Rutgers University Press.

- ^ Henrici de Segusio, Cardinalis Hostiensis, Summa aurea, Venice 1574, col. 612.

- ^ Rolker, Christof (2014-01-01). "The two laws and the three sexes: ambiguous bodies in canon law and Roman law (12th to 16th centuries)". Zeitschrift der Savigny-Stiftung für Rechtsgeschichte: Kanonistische Abteilung. 100 (1): 178–222. doi:10.7767/zrgka-2014-0108. ISSN 2304-4896. S2CID 159668229.

- ^ "Henry de Bracton". Encyclopædia Britannica (2009). Retrieved 17 March 2009. Archived 2009-03-24 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ de Bracton, Henry. On the Laws and Customs of England. Vol. 2 (Thorne ed.). p. 31. Archived from the original on 2016-10-29.

- ^ de Bracton, Henry. On the Laws and Customs of England. Vol. 2 (Thorne ed.). p. 32. Archived from the original on 2016-10-29.

- ^ Bychowski, M. W. (June 2018). "The Isle of Hermaphrodites: Disorienting the place of intersex in the Middle Ages". Postmedieval. 9 (2): 161–178. doi:10.1057/s41280-018-0079-1. ISSN 2040-5960. S2CID 166086082.

- ^ Morland, Iain (June 2018). "Afterword: Genitals are history". Postmedieval. 9 (2): 209–215. doi:10.1057/s41280-018-0083-5. ISSN 2040-5960. S2CID 187569252.

- ^ Coke, Edward (1812). The Institutes of the Laws of England (1st American ed.). Part 1, 8.a.

- ^ Greenberg, Julie (1999). "Defining Male and Female: Intersexuality and the Collision Between Law and Biology". Arizona Law Review. 41: 277–278. SSRN 896307.

- ^ Sirāj al-Dīn Muḥammad ibn Muḥammad Sajāwandī (1792). Al Sirájiyyah: Or, the Mohammedan Law of Inheritance. Translated by Jones, William.

- ^ Allgemeines Landrecht für die Preußischen Staaten. 1 June 1794. Part 1, section 20. Retrieved 2018-10-31.

- ^ Reis, Elizabeth (September 2005). "Impossible Hermaphrodites: Intersex in America, 1620–1960". The Journal of American History. 92 (2): 411–441. doi:10.2307/3659273. JSTOR 3659273.

- ^ Barbin, Herculine (1980). Herculine Barbin: Being the Recently Discovered Memoirs of a Nineteenth-century French Hermaphrodite. Translated by McDougall, Richard. introd. Michel Foucault. New York: Pantheon Books. ISBN 978-0-394-50821-4.

- ^ "'Extraordinary Circumstance' hermaphrodite child". The Welshman. 7 November 1981.

- ^ "Hermaphrodite Child - Curious Phenomenon at Cardiff". The Cambrian. 25 May 1906. p. 2. at the National Library of Wales

- ^ von Neugebauer, Franz Ludwig (1908). Hermaphroditismus beim Menschen. Leipzig: Dr. Werner Klinkhardt. pp. 1–764.

- ^ Goldschmidt, Richard (1915). "Vorläufige Mitteilung über weitere Versuche zur Vererbung und Bestimmung des Geschlechts". Biologisches Centralblatt (in German). 35. Leipzig: Georg Thieme: 566.

- ^ Satzinger, Helga (2004). Rasse, Gene und Geschlecht – Zur Konstituierung zentraler biologischer Begriffe bei Richard Goldschmidt und Fritz Lenz, 1916–1936 (PDF) (in German). Berlin: Max-Planck-Gesellschaft zur Förderung der Wissenschaften. p. 15.

- ^ Goldschmidt, Richard (1916). "Die biologischen Grundlagen der konträren Sexualität und des Hermaphroditismus beim Menschen". Archiv für Rassen- und Gesellschaftsbiologie einschließlich Rassen- und Gesellschaftshygiene. 12 (1). Berlin: Archiv-Gesellschaft: 1–14.

- ^ Mathes, Paul (1924). Halban, Josef; Seitz, Ludwig (eds.). "Die Konstitutionstypen des Weibes, insbesondere der intersexuelle Typus". Biologie und Pathologie des Weibes. Berlin: Urban & Schwarzenberg: 1–112.

- ^ Satzinger, Helga (2004). Rasse, Gene und Gesellschaft. Zur Konstituierung zentraler biologischer Begriffe bei Richard Goldschmidt und Fritz Lenz (PDF). Berlin: Max-Planck-Gesellschaft zur Förderung der Wissenschaften. pp. 17–20.

- ^ Naujoks, Hans (1934). "Über echte Zwitterbildung beim Menschen und ihre therapeutische Beeinflussung" (PDF). Zeitschrift für Geburtshlfe und Gynäkologie. 109. Berlin: W. Stoeckel: 139–140, 149.

- ^ Naujoks, Hans (1934). "Über echte Zwitterbildung beim Menschen und ihre therapeutische Beeinflussung" (PDF). Zeitschrift für Geburtshilfe und Gynäkologie. 109. Berlin: W. Stoeckel: 135–161.

- ^ Lenz, Fritz (1936). "Anomalien der Körperform". Menschliche Erblehre und Rassenhygiene (Eugenik). München: J. F. Lehmanns Verlag. Volume I, section 3: Die krankhaften Erbanlagen, p.403.

- ^ Obermaier, Frederick (2007-10-22). "Auge in Auge mit Todesengel Mengele". Der Spiegel (in German). Retrieved 2018-10-31.

- ^ Armstrong, C. N. (1964). "Intersexuality in Man". In Armstrong, C. N.; Marshall, A. J. (eds.). Intersexuality in Vertebrates Including Man. London, New York: Academic Press.

- ^ Dewhurst, S. J.; Gordon, R. R. (1969). The Intersexual Disorders. London: Baillière Tindall & Cassell.

- ^ Eder, Sandra (2014). Historische Evaluation der Behandlung von Patienten und Patientinnen mit Besonderheiten der Geschlechtsentwicklung am Kinderspital Zürich (PDF) (in German). Zürich: University of Zürich. pp. 17, 18.

- ^ Dohle, Max; Ettema, Dick (2012). "Foekje Dillema". Archived from the original on 2016-04-22. Retrieved 2016-05-28.

- ^ "A Lab is Set to Test the Gender of Some Female Athletes". New York Times. 30 July 2008. Archived from the original on 4 September 2017.

- ^ In the marriage of C and D (falsely called C), FLC 90-636 (1979).

- ^ "Olympic track star Stella Walsh dies". Wilmington Morning Star. December 6, 1980. Retrieved August 23, 2016.

- ^ "Stella Walsh Slain; Olympic Track Star". The New York Times. December 6, 1980. p. 20. ProQuest 121246455.

- ^ Tullis, Matt (27 June 2013). "Who was Stella Walsh? The story of the intersex Olympian". SB Nation. Archived from the original on 2017-07-28.

- ^ Androgen Insensitivity Syndrome Support Group Australia; Briffa, Anthony (22 January 2003). "Discrimination against People affected by Intersex Conditions: Submission to NSW Government" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 11 March 2016. Retrieved 2016-05-16.

- ^ a b Astraea Lesbian Foundation for Justice (June 2016). "We Are Real: The Growing Movement Advancing the Human Rights of Intersex People" (PDF).

- ^ Martínez-Patiño, Maria José (December 2005). "Personal Account: A woman Tried and Tested". The Lancet. 366: 366–538. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(05)67841-5. PMID 16360746. S2CID 8742433.

- ^ Simpson JL, Ljungqvist A, de la Chapelle A, et al. (November 1993). "Gender verification in competitive sports". Sports Medicine. 16 (5): 305–15. doi:10.2165/00007256-199316050-00002. PMID 8272686. S2CID 43814501.

- ^ Chase, Cheryl (July–August 1993). "Letters from readers" (PDF). The Sciences: 25. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2006-09-28.

- ^ Beck, Max. "Hermaphrodites with Attitude Take to the Streets". Intersex Society of North America. Archived from the original on 2015-10-05. Retrieved 2015-10-24.

- ^ Diamond, Milton (1982). "Sexual Identity, Monozygotic Twins Reared in Discordant Sex Roles and a BBC Follow-Up". Archives of Sexual Behavior. 11 (2). University of Hawaii: 181–186. doi:10.1007/BF01541983. PMID 6889847. S2CID 45440589. Archived from the original on 5 August 2011. Retrieved 1 August 2011.

- ^ Diamond, Milton; Sigmundson, H. Keith (October 1997). "Management of intersexuality. Guidelines for dealing with persons with ambiguous genitalia". Archives of Pediatrics and Adolescent Medicine. 151 (10): 1046–50. doi:10.1001/archpedi.1997.02170470080015. PMID 9343018. Archived from the original on 9 May 2013. Retrieved 24 April 2013.

- ^ Curtis, Skyler (2010–2011). "Reproductive Organs and Differences of Sex Development: The Constitutional Issues Created by the Surgical Treatment of Intersex Children". McGeorge Law Review. 42: 863. Archived from the original on 18 December 2014. Retrieved 15 November 2012.

- ^ Bödeker, Heike (2016). "Intersexualität, Individualität, Selbstbestimmtheit und Psychoanalyse Ein Besinnungsaufsatz". In Michaela Katzer; Heinz-Jürgen Voß (eds.). Geschlechtliche, sexuelle und reproduktive Selbstbestimmung (in German). Gießen: Psychosozial-Verlag. pp. 117–136. doi:10.30820/9783837967999-117. ISBN 978-3-8379-2546-3.

- ^ Koshie, Nihal (September 9, 2018). "The rising star who ended her life much before Dutee Chand challenged the rules". The Indian Express. Retrieved 2018-09-10.

- ^ Prabhudesai, Sandesh (October 11, 2001). "Mystery of Pratima's suicide". Goa News. Retrieved 2018-09-10.

- ^ Nagvenkar, Mayabhushan (July 21, 2012). "Goa's Pinki Pramanik". Newslaundry. Retrieved 2018-09-10.

- ^ "X marks the spot for intersex Alex" (PDF). West Australian. 11 January 2003. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2013-11-10 – via Bodies Like Ours.

- ^ Holme, Ingrid (2008). "Hearing People's Own Stories". Science as Culture. 17 (3): 341–344. doi:10.1080/09505430802280784. S2CID 143528047.

- ^ "Judicial Matters Amendment Act, No. 22 of 2005, Republic of South Africa, Vol. 487, Cape Town" (PDF). 11 January 2006. Archived (PDF) from the original on 23 July 2015.

- ^ Human Rights Commission of the City and County of San Francisco; de María Arana, Marcus (2005). A Human Rights Investigation into the Medical 'Normalization' of Intersex People. San Francisco. Archived from the original on 2013-12-28.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Hughes, I. A.; Houk, C.; Ahmed, S. F.; Lee, P. A.; LWPES1/ESPE2 Consensus Group (June 2005). "Consensus statement on management of intersex disorders". Archives of Disease in Childhood. 91 (7): 554–563. doi:10.1136/adc.2006.098319. ISSN 0003-9888. PMC 2082839. PMID 16624884.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ Motshegwa, Lesogo; Gerald Imray (2010-07-06). "World champ Semenya cleared to return to track". Yahoo!. Associated Press. Archived from the original on July 15, 2010. Retrieved 2010-07-06.

- ^ International Commission of Jurists (2010). "Richard Muasya v. the Hon. Attorney General, High Court of Kenya (2 December 2010)". International Commission of Jurists.

- ^ Canning, Paul (10 December 2011), "Australia town believed to have elected world's first intersex mayor", World News Australia, archived from the original on 4 January 2012

- ^ National Advisory Commission on Biomedical Ethics, Switzerland (November 2012). On the management of differences of sex development. Ethical issues relating to 'intersexuality'. Opinion No. 20/2012 (PDF). Berne. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2015-04-23.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ "Condenan al H. de Talca por error al determinar sexo de bebé". diario.latercera.com (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 24 November 2012. Retrieved 15 February 2017.

- ^ García, Gabriela (2013-06-20). "Identidad forzada". www.paula.cl (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 2017-02-15.

- ^ "Report of the UN Special Rapporteur on Torture" (PDF). Office of the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights. February 2013. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2016-08-24.

- ^ Center for Human Rights & Humanitarian Law; Washington College of Law; American University (2014). Torture in Healthcare Settings: Reflections on the Special Rapporteur on Torture's 2013 Thematic Report. Washington, DC: Center for Human Rights & Humanitarian Law. Archived from the original on 2016-03-14.

- ^ Jordan-Young, R. M.; Sonksen, P. H.; Karkazis, K. (April 2014). "Sex, health, and athletes". BMJ. 348 (apr28 9): –2926–g2926. doi:10.1136/bmj.g2926. ISSN 1756-1833. PMID 24776640. S2CID 2198650.

- ^ Fénichel, Patrick; Paris, Françoise; Philibert, Pascal; Hiéronimus, Sylvie; Gaspari, Laura; Kurzenne, Jean-Yves; Chevallier, Patrick; Bermon, Stéphane; Chevalier, Nicolas; Sultan, Charles (June 2013). "Molecular Diagnosis of 5α-Reductase Deficiency in 4 Elite Young Female Athletes Through Hormonal Screening for Hyperandrogenism". The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism. 98 (6): –1055–E1059. doi:10.1210/jc.2012-3893. ISSN 0021-972X. PMID 23633205.

- ^ a b Senate of Australia; Community Affairs References Committee (2013). Involuntary or coerced sterilisation of intersex people in Australia. Canberra. ISBN 978-1-74229-917-4. Archived from the original on 2015-09-23.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ "Resolution 1952/2013, Provision version, Children's right to physical integrity". Council of Europe. 1 October 2013. Archived from the original on 21 July 2015.

- ^ Viloria, Hida (November 6, 2013). "Op-ed: Germany's Third-Gender Law Fails on Equality". The Advocate. Archived from the original on November 10, 2013.

- ^ "3rd International Intersex Forum concluded". Archived 2013-12-04 at the Wayback Machine, ILGA-Europe (Creative Commons statement), 2 December 2013

- ^ "Global intersex community affirms shared goals". Archived 2013-12-06 at the Wayback Machine, Star Observer, December 4, 2013

- ^ "Public Statement by the Third International Intersex Forum". Archived 2013-12-27 at the Wayback Machine, Advocates for Informed Choice, 12 December 2013

- ^ "Public statement by the third international intersex forum". Archived 2013-12-26 at the Wayback Machine, Organisation Intersex International Australia, 2 December 2013

- ^ "Derde Internationale Intersekse Forum" (in Dutch). Archived 2013-12-20 at the Wayback Machine, Nederlandse Netwerk Intersekse/DSD (NNID), 3 December 2013

- ^ "Public Statement by the Third International Intersex Forum". Archived 2013-12-26 at the Wayback Machine, IVIM/OII-Germany, 1 December 2013 (in German)

- ^ 2013 第三屆世界陰陽人論壇宣言 (in Chinese). Archived 2013-12-26 at the Wayback Machine, Oii-Chinese, December 2013

- ^ Migiro, Katy. "Kenya takes step toward recognizing intersex people in landmark ruling". Reuters. Archived from the original on 2015-09-24.

- ^ WHO; OHCHR; UN Women; UNAIDS; UNDP; UNFPA; UNICEF (2014). Eliminating forced, coercive and otherwise involuntary sterilization: An interagency statement (PDF). ISBN 978-92-4-150732-5. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2016-11-09.

- ^ Council of Europe; Commissioner for Human Rights (April 2015), Human rights and intersex people, Issue Paper, archived from the original on 2016-01-06

- ^ Court of Arbitration for Sport (July 2015). CAS 2014/A/3759 Dutee Chand v. Athletics Federation of India (AFI) & The International Association of Athletics Federations (IAAF) (PDF). Court of Arbitration for Sport. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2017-07-04.

- ^ The Local (February 27, 2015). "Intersex person sues clinic for unnecessary op". Archived from the original on December 14, 2015. Retrieved 2015-12-21.

- ^ StopIGM.org (December 17, 2015). "Nuremberg Hermaphrodite Lawsuit: Michaela 'Micha' Raab Wins Damages and Compensation for Intersex Genital Mutilations!". Archived from the original on May 11, 2016. Retrieved 2015-12-21.

- ^ "Introducing the Intersex Fund team at Astraea!". Astraea Lesbian Foundation for Justice. June 16, 2015. Archived from the original on July 3, 2015. Retrieved 2015-07-02.

- ^ "Boost for Intersex activists and organisations". SOGI News.com. RFSL. January 16, 2015. Archived from the original on July 4, 2015. Retrieved 2015-07-02.

- ^ Parliament of Uganda (2015), Registration of Persons Act, archived from the original on 2017-05-01

- ^ a b Support Initiative for Persons with Congenital Disorders (2016), Baseline Survey on Intersex Realities in East Africa – Specific Focus on Uganda, Kenya and Rwanda

- ^ "Chilean Government Stops the 'Normalization' of Intersex Children". OutRight Action International. January 14, 2016. Archived from the original on July 5, 2016.

- ^ "Chilean Ministry of Health issues instructions stopping 'normalising' interventions on intersex children". Organisation Intersex International Australia. 11 January 2016. Archived from the original on 10 March 2017. Retrieved 3 January 2017.

- ^ UN Committee against Torture; UN Committee on the Rights of the Child; UN Committee on the Rights of People with Disabilities; UN Subcommittee on Prevention of Torture and other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment; Juan Méndez, Special Rapporteur on torture and other cruel, inhuman, or degrading treatment or punishment; Dainius Pῡras, Special Rapporteur on the right of everyone to the enjoyment of the highest attainable standard of physical and mental health; Dubravka Šimonoviæ, Special Rapporteur on violence against women, its causes and consequences; Marta Santos Pais, Special Representative of the UN Secretary-General on Violence against Children; African Commission on Human and Peoples' Rights; Council of Europe Commissioner for Human Rights; Inter-American Commission on Human Rights (October 24, 2016). "Intersex Awareness Day – Wednesday 26 October. End violence and harmful medical practices on intersex children and adults, UN and regional experts urge". Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights. Archived from the original on November 21, 2016.

- ^ "United Nations for Intersex Awareness". United Nations Free & Equal campaign. October 2016. Archived from the original on 2016-11-12.

- ^ Klöppel, Ulrike (December 2016). "Zur Aktualität kosmetischer Operationen 'uneindeutiger' Genitalien im Kindesalter". Gender Bulletin (in German) (42). ISSN 0947-6822. Archived from the original on 2017-02-04.

- ^ Sénat; Blondin, Maryvonne; Bouchoux, Corinne (February 23, 2017). Variations du développement sexuel : lever un tabou, lutter contre la stigmatisation et les exclusions. 2016–2017. Paris, France: Sénat. Archived from the original on March 31, 2017.

- ^ Ballet, Virginie (March 17, 2017). "Hollande prône l'interdiction des chirurgies sur les enfants intersexes". Libération. Archived from the original on March 25, 2017.

- ^ a b Androgen Insensitivity Support Syndrome Support Group Australia; Intersex Trust Aotearoa New Zealand; Organisation Intersex International Australia; Black, Eve; Bond, Kylie; Briffa, Tony; Carpenter, Morgan; Cody, Candice; David, Alex; Driver, Betsy; Hannaford, Carolyn; Harlow, Eileen; Hart, Bonnie; Hart, Phoebe; Leckey, Delia; Lum, Steph; Mitchell, Mani Bruce; Nyhuis, Elise; O'Callaghan, Bronwyn; Perrin, Sandra; Smith, Cody; Williams, Trace; Yang, Imogen; Yovanovic, Georgie (March 2017), Darlington Statement, archived from the original on 2017-03-22, retrieved March 21, 2017

- ^ Copland, Simon (March 20, 2017). "Intersex people have called for action. It's time to listen". Special Broadcasting Service. Archived from the original on March 22, 2017. Retrieved 2017-03-21.

- ^ Jones, Jess (March 10, 2017). "Intersex activists in Australia and New Zealand publish statement of priorities". Star Observer. Archived from the original on March 22, 2017. Retrieved 2017-03-21.

- ^ Power, Shannon (March 13, 2017). "Intersex advocates pull no punches in historic statement". Gay Star News. Archived from the original on March 22, 2017. Retrieved 2017-03-21.

- ^ Sainty, Lane (March 13, 2017). "These Groups Want Unnecessary Surgery On Intersex Infants To Be Made A Crime". BuzzFeed Australia. Archived from the original on March 22, 2017. Retrieved 2017-03-21.

- ^ OII Europe; Bilitis; Intersex Belgium; Intersex Iceland; Intersex Russia; Intersex Scandinavia; NNID; OII Germany; OII-Italia; OII Netherlands; TRIQ Inter*-Projekt; X-Y Spectrum (April 20, 2017). "STATEMENT of the 1st European Intersex Community Event (Vienna, 30st – 31st of March 2017)". OII Europe. Archived from the original on June 28, 2017. Retrieved 2017-05-26.

- ^ Amnesty International (2017). First, Do No Harm. Archived from the original on 2017-05-17.

- ^ Amnesty International (2017). "First, Do No Harm: ensuring the rights of children born intersex". Archived from the original on 2017-05-11. Retrieved 2017-05-13.

- ^ Elders, M Joycelyn; Satcher, David; Carmona, Richard (June 2017). "Re-Thinking Genital Surgeries on Intersex Infants" (PDF). Palm Center. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2017-07-28.

- ^ Weiss, Suzannah (June 30, 2017). "These Doctors Want Us To Stop Pathologizing Intersex People". Refinery29. Archived from the original on July 1, 2017. Retrieved 2017-06-30.

- ^ Power, Shannon (June 29, 2017). "'Stunning victory' as US Surgeons General call for an end to intersex surgery". Gay Star News. Archived from the original on July 12, 2017. Retrieved 2017-06-30.

- ^ Human Rights Watch; interACT (July 2017). I Want to Be Like Nature Made Me. Human Rights Watch. ISBN 978-1-62313-502-7. Archived from the original on 2017-10-05.

- ^ Lang, Nico (December 7, 2017). "Betsy Driver Is Ready for America's Intersex Tipping Point". INTO. Archived from the original on 2018-09-05. Retrieved 2018-09-05.

- ^ African Intersex Movement (December 2017), Public Statement by the African Intersex Movement, retrieved 2018-09-05

- ^ Intersex Asia (February 2018). "Statement of Intersex Asia and Asian intersex forum". Retrieved 2018-09-05.

- ^ Participants at the Latin American and Caribbean Regional Conference of Intersex Persons (April 13, 2018). "San José de Costa Rica Statement". Brújula Intersexual. Retrieved 2018-09-05.

- ^ "Kabinett beschließt Änderung des Personenstandsgesetzes". Bundesministerium des Innern, für Bau und Heimat (in German). Retrieved 2018-10-30.

- ^ Federal Constitutional Court (2017-10-10). "Bundesverfassungsgericht – Decisions – Civil status law must allow a third gender option". Retrieved 2018-10-30.

- ^ OII Europe (August 2018). "New draft bill in Germany fails to protect intersex people". Retrieved 2018-09-10.

- ^ Littlefield, Amy (August 13, 2018). "Intersex People Want to End Nonconsensual Surgeries. A California Resolution Is Their 'Warning Shot'". Rewire.News. Retrieved 2018-09-05.

- ^ Miller, Susan (August 28, 2018). "California becomes first state to condemn intersex surgeries on children". USA TODAY. Retrieved 2018-09-05.

- ^ "Caster Semenya: Olympic 800m champion loses appeal against IAAF testosterone rules". BBC Sport. 1 May 2019. Retrieved 2 May 2019.

- ^ Court of Arbitration for Sport (2019-05-01), Semenya, ASA and IAAF: Executive Summary (PDF), paragraph 6, retrieved 2019-06-01

- ^ "'The IAAF will not drug me or stop me being who I am': Semenya appeals against Cas ruling". The Guardian. 29 May 2019. Retrieved 29 May 2019.

- ^ Intersex Human Rights Australia (2019-05-23). "Joint statement on the International Classification of Diseases 11".

- ^ Crittenton, Anya (2019-05-24). "World Health Organization condemned for classifying intersex as 'disorder'". Gay Star News. Archived from the original on 2020-02-20. Retrieved 2019-06-02.

- ^ Leighton-Dore, Samuel (2019-05-28). "World Health Organisation drops transgender from list of mental health disorders". SBS. Retrieved 2019-06-02.

- ^ Barr, Sabrina (2019-05-28). "Transgender no longer classified as 'mental disorder' by WHO". The Independent. Retrieved 2019-06-02.

- ^ Wills, Ella (2019-05-29). "Campaigners hail changes to WHO classification of trans health issues". Evening Standard. Retrieved 2019-06-02.

- ^ "Joint statement to the Congregation for Catholic Education". Intersex Human Rights Australia. 2019.

- ^ "Male and Female He Created Them" (PDF). Vatican City: Congregation for Catholic Education. 2019.

- ^ "'Transwoman A "Bride" Under Hindu Marriage Act': Madras HC; Also Bans Sex Re-Assignment Surgeries On Intersex Children". 23 April 2019. Archived from the original on 2019-07-12. Retrieved 2019-04-24.

- ^ Human Rights Watch (29 August 2019). "Indian State Bans Unnecessary Surgery on Intersex Children". Archived from the original on 2021-01-20. Retrieved 2019-08-30.

- ^ "Ruling on intersex infants: Madurai activist comes in for praise by HC". Times of India. 24 April 2019. Retrieved 30 June 2022.

- ^ "Information Toolkit-Human Rights of Intersex Persons in India" (PDF). apcom.org. 1st National Intersex Human Rights Conference. May 2020. p. 6. Retrieved 30 June 2022.

- ^ "Intersex Care at Lurie Children's and Our Sex Development Clinic". www.luriechildrens.org. Retrieved 2021-09-13.