Jones Law (Philippines)

| |

| Long title | An Act To declare the purpose of the people of the United States as to the future political status of the people of the Philippine Islands, and to provide a more autonomous government for those islands. |

|---|---|

| Enacted by | the 64th United States Congress |

| Citations | |

| Public law | 64-240 |

| Statutes at Large | 39 Stat. 545 |

| Legislative history | |

| |

|

|---|

|

|

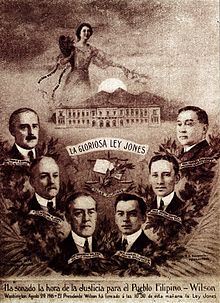

The Jones Law (39 Stat. 545, also known as the Jones Act, the Philippine Autonomy Act, and the Act of Congress of August 29, 1916) was an Organic Act passed by the United States Congress. The law replaced the Philippine Organic Act of 1902 and acted as a constitution of the Philippines from its enactment until 1934, when the Tydings–McDuffie Act was passed (which in turn led eventually to the Commonwealth of the Philippines and to independence from the United States). The Jones Law created the first fully elected Philippine legislature.

The law was enacted by the 64th United States Congress on August 29, 1916, and contained the first formal and official declaration of the United States federal government's commitment to grant independence to the Philippines.[1] It was a framework for a "more autonomous government", with certain privileges reserved to the United States to protect its sovereign rights and interests, in preparation for the grant of independence by the United States. The law provides that the grant of independence would come only "as soon as a stable government can be established", which was to be determined by the United States Government itself.

The law also changed the Philippine Legislature into the Philippines' first fully elected body and therefore made it more autonomous of the U.S. government. The 1902 Philippine Organic Act provided for an elected lower house (the Philippine Assembly), while the upper house (the Philippine Commission) was appointed.[2] The Jones Law provided for both houses to be elected[2] and changed the name of the Philippine Assembly to the House of Representatives. The executive branch continued to be headed by an appointed governor general of the Philippines, always an American.

Elections were held on October 3, 1916 for the newly created Philippine Senate. Elections to the Philippine Assembly had already been held on June 6, 1916, and those elected in that election were made members of the House of Representatives by the law.

Development of the bill

[edit]The ultimate goal for the Philippines was independence. U.S. President Theodore Roosevelt said as early as 1901, "We hope to do for them what has never been done for any people of the tropics—to make them fit for self-government after the fashion of really free nations."[3] The American public tended to view America's presence in the Philippines as unremunerative and expensive, so Roosevelt had concluded by 1907, "We shall have to be prepared for giving the islands independence of a more or less complete type much sooner than I think advisable."[3]

Woodrow Wilson said, during the 1912 election campaign which made him U.S. President, "The Philippines are at present our frontier but I hope we presently are to deprive ourselves of that frontier."[3] Even before the 1912 elections, U.S. House Committee on Insular Affairs Chairman William Atkinson Jones attempted to launch a bill that would set a fixed date for Philippine independence.[4] Manuel L. Quezon was one of the Philippines' two resident commissioners to the U.S. House of Representatives. Jones delayed launching his bill, so Quezon drafted the first of two "Jones Bills". He drafted a second Jones Bill in early 1914 after the election of Wilson as U.S. president and his appointment of Francis Burton Harrison as president of the Philippine Commission and governor general of the Philippines.[citation needed]

Wilson had informed Quezon of his hostility to any fixed timetable for independence, and Quezon believed that the draft bill contained enough flexibility to suit Wilson.[5]

Passage into law

[edit]The bill passed the House of Representatives in October 1913 and went to the Senate, backed by Harrison, U.S. Secretary of War Lindley Garrison, and President Wilson. A final version of the bill was signed into U.S. law by President Wilson on August 29, 1916, after amendment by the Senate and further changes in a congressional conference committee.[5]

Terms

[edit]

Among the provisions of the law was the creation of an all-Filipino legislature. It created the Philippine Senate to replace the Philippine Commission, which had served as the upper chamber of the legislature.[2]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ In the "Instructions of the President to the Philippine Commission Archived 2009-02-27 at the Wayback Machine" dated April 7, 1900, President William McKinley reiterated the intentions of the United States Government to establish and organize governments, essentially popular in their form, in the municipal and provincial administrative divisions of the Philippine Islands. However, there was no official mention of any declaration of Philippine Independence.

- ^ a b c Philippine Autonomy Act (Jones Law)

- ^ a b c Ninkovich 2004, p. 75

- ^ Kramer 2006, p. 353

- ^ a b Kramer 2006, p. 354

Bibliography

[edit]- Kramer, Paul Alexander (2006). The Blood of Government: Race, Empire, the United States, & the Philippines. UNC Press. ISBN 978-0-8078-5653-6.

- Ninkovich, Frank A. (2004). The United States and Imperialism. Blackwell Publishing. ISBN 978-1-57718-056-2.

External links

[edit]- Jones Law as enacted (details) in the US Statutes at Large

- "The Philippine Autonomy Act". Corpus Juris online Philippine law library. July 1902. Retrieved January 13, 2008.