Karelians

This article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these messages)

|

| |

| Regions with significant populations | |

|---|---|

| 60,815 (2010)[3] | |

| 10,000 (1994)[4] | |

| 1,522 (2001)[5] | |

| 524 (1999)[6] | |

| 363 (2011)[7] | |

| Languages | |

| Karelian, Finnish, Russian | |

| Religion | |

| Orthodox Christianity Lutheran | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| other Baltic Finns | |

The Karelians (Template:Lang-krl) are a nation that belongs to Baltic-Finnic ethnic group that are currently living in Finland and Russia. In Russia Karelians mostly settle in the Republic of Karelia and in other north-western parts of the Russian Federation. There are also significant Karelian enclaves in the Tver and Novgorod region, as some Karelians migrated to those areas after Swedish-Russian War of 1656-58. In Finland they traditionally settle in the regions of Savonia and Northern and Southern Karelia. The historic homeland of the Karelians has been the Karelian Isthmus, Ladoga Karelia, Olonets Karelia in Russia and the provinces of Northern and Southern Karelia and Savonia in Finland.

History

The first written mention of Karelia and Karelians occurs in Scandinavian sources. Several old Scandinavian sagas and chronicles refer to Karelia sometimes as Karjalabotn,[8] Kirjalabotnar[9] or Kirjaland,[10] which means that Karelians and Karelia were known to the Vikings as early as 7 century AD. Another mention of Karelians in Scandinavian sources is The Chronicle of Erik.[11] Part of the Chronicle mentions a Karelian raid to the, then notable, Swedish town of Sigtuna in 1187 and its subsequent pillage. This mention of Karelian raids on Sweden in the chronicle is given as the main reason to found Stockholm - the current capital of Sweden.[11]

The first mention of Karelians in ancient Russian chronicles is dated 1143 AD[12] when the Novgorod chronicle mentions that Karelians raided neighbouring Tavastia (Häme). Ancient Russian chronicles referred to ancient Karelians as Koryela. Until the end of 13th century Karelians have enjoyed period of relative independence and self-government. However, as Karelians came in contact with Novgorod some of them started to take part in the Novgorodian internal and external politics. Russian chronicles mention joint raid of Novgorod and Karelians on Tavastia in 1191. In 12th-century Karelian relationship with Novgorod undergoes significant changes, from partnership and alliance to an attempt to dominance by the later:

In 1227 an attempt is made to convert Karelians to Greek Orthodoxy.[13] In 1253, Karelians are aiding Novgorod in its wars with Estonians.[14] In 1269 AD The duke of Novgorod is planning a raid against Karelians. Plans are abandoned as he is advised against it by his councilors.[15] In 1278, Novgorod makes war against Karelians and according to the chronicle puts Karelian lands "to sword and fire", which significantly reduces Karelian military power.[16]

While Novgorod was unsuccessfully trying to subdue Karelians, Sweden was successfully doing the same with the neighbouring Finnish tribes. In 1293 Swedes raided Karelian lands and successfully founded a castle of Vyborg on the site of an ancient Karelian settlement.[11] Sweden began to convert the local Karelian population to Roman Catholicism. In 1295, Sweden attempted to establish a complete dominance of Karelian lands by founding a castle of Köxholm on the site of ancient Karelian settlement of Käkisalmi (Koryela in Russian chronicles). However this time Novgorod manages to repel Swedish attack by capturing and burning down the castle. After this both Sweden and Novgorod engage in the long conflict over dominance of Karelians and their lands.[17]

In 1314 AD Karelians rebel over the attempt to convert them to Christianity according to the Novgorod chronicle. It is interesting to note that first rebellion started against Russian Orthodixy by capturing Käkisalmi and killing all Christians there. Then the rebelling spreads over all Karelian lands, which sufficiently weakens Novgorodian influence.[18]

In 1323 AD, Karelians suffer a forceful sundering as Sweden and Novgorod divide Karelian lands and their inhabitants by signing a peace agreement. The agreement transfers governance of all western Karelian lands to Swedish sovereignty, while eastern Karelian lands fall under Novgorodian rule. This sundering started a long process of separation of Karelians into two different halves which main difference being the religion as western Karelians became first Roman Catholic and later Lutheran, while eastern Karelians were converted to Greek Orthodoxy.[19]

Subsequent wars have shown that Karelians were fighting on both sides of the conflict and often against each other. At the same time Karelians on the Novgorodian and later Russian side of the border continued to settle northward towards the White Sea. By later 14th century Russian Karelians established control over White Karelia and come in conflict with Norwegians of Kola.

As the struggle for power in the region continued over the next centuries the borderline between Sweden and Russia moved several times with most of the changes happening in Northern Karelia and Kajnuu. However, in 1617, history of Karelians underwent a significant change as Russia ceded to Sweden, along with other territories, eastern part of Karelian Isthmus, Ladoga Karelia and certain parts of Northern Karelia. This meant that the majority of Karelians were again living in one country yet it did not bring peace to Karelian people. As Sweden commenced the process of conversion of population of the ceded territories to Lutheran Protestantism they have met with resistance among Old-Believer Orthodox Karelians and neighbouring OrthodoxIzhorians.

By mid-17th century the tension between the Lutheran Swedish government and Orthodox Karelians led to yet another war between Sweden and Russia in 1656-1658 as Russia attempted to recapture territories with sympathizing Orthodox population. Some of the local Karelian population that remained Orthodox aided Russian armed forces as they waged war on Karelian territories but after two years of fighting both sides came to a stand-still.

Many of the Karelians who remained Orthodox by 1658 AD were unwilling to remain in Sweden refusing to convert to Lutheranism, which triggered a mass migration of many Orthodox Karelians from these areas into other parts of Russia, with some migrating to the region of Tver and forming the Tver Karelians minority, while others moving to the region of Valdai in Novgorod region and yet others moving to White Karelia by the White Sea.

As some of the lands in eastern Karelian Isthmus and Ladoga Karelia became partially depopulated Sweden decided to move settlers from Savonia to those Karelian lands which resulted to mixture of local Karelians and Savonians in some areas. However, with Savonians themselves being of Karelian origin, this migration although affected local Karelians religiously (as majority of the population became Lutheran) and to some extent linguistically, it did not bring major changes to the ethnic map of the Karelia.

The next change happened in 1721 as Russia won the great northern war against Sweden 1700-21, which forced Sweden to cede the entire Karelian Isthmus and Ladoga Karelia to Russia, with its now mostly Lutheran population. Although there were attempts to convert local population to Orthodoxy there did not meet with any success.

After Russia conquered the entire Finnish territories in yet another Russo-Swedish war in 1808-09 it was decided to join Karelian Isthmus and Ladoga Karelia to the newly formed Grand Duchy of Finland in 1812, which brought all western Karelians into the same state with Finns. While eastern Karelians remained under independent Russian administration. Although Karelians ended up in the same country the religious difference between eastern and western Karelians remained a dividing factor, which somewhat affected the linguistics but even until the beginning of the 20th century both groups could understand each other. Yet it has to be noted that eastern Karelians have managed to preserve traditions and folklore better than their western brothers.

As the Grand Duchy of Finland was formed its inhabitants struggled to properly identify themselves ethnically. With some being Finnish, some Swedish and some Karelian. As the Fennoman movement started and the new Finnish nation commenced its forming and shaping process attempts were made to restore the lost Finnish identity. The process of "finnisation" of Finland have started. As part of that process during the 19th century Finnish folklorists including Elias Lönnrot traveled to different parts of Eastern Karelia to gather folklore and epic poetry. The Orthodox Karelians in North Karelia and Russia were now seen as close brethren or even a sub-group of the Finns. The ideology of Karelianism inspired Finnish artists and researchers, who believed that the Orthodox Karelians had retained elements of an archaic, original Finnish culture which had disappeared from Finland. This have led to numerous confusions with some claiming that western and eastern Karelians being different nations etc.

As Finland gained its independence in 1917 the process of "finnisation" continued yet even eastern Karelians were now viewed as part of the Finnish nation. In 1918-22 eastern Karelians have made several attempts to gain their own independence from Russia with a common notion to cede to Finland which was met with warm welcome in Finland. Yet intervention of Antanta and first White Russian government and later Soviet government into the process led to bloodshed among eastern Karelians as the Uhta Republic and Olonets gevernment were crushed and destroyed by the Soviet forces. Several thousands of eastern Karelians have migrated to Finland by 1922 from different parts of Eastern Karelia.

As the Winter War between Finland and USSR took place Finland had to cede Karelian Isthmus and Ladoga Karelia to USSR. As local Karelian population was unwilling to end up under Soviet rulethis triggered over 400,000 people were evacuated over Finland's new border from the territories that were to be ceded. After the Continuation War 1941-1944 as Finland temporarily held most of the eastern Karelia Several thousands of Karelians chose to migrate to Finland as the Finnish forces were retreating to main Finland in 1944 AD. The Karelians that migrated to Finland in the 20th century were initially Karelian-speaking, but due to minor lingual differences and in order to assimilate into the local communities soon adopted the Finnish language after the war. Some of the evacuees have later immigrated, mainly to Sweden, to Australia and to North America.

The Russian Karelians, living in the Republic of Karelia, are nowadays rapidly being absorbed into the Russian population. This process began several decades ago. For example, it has been estimated that even between the 1959 and 1970 Soviet censuses, nearly 30 percent of those who were enumerated as Karelian by self-identification in 1959 changed their self-identification to Russian 11 years later.[20]

Language

This section relies largely or entirely on a single source. (March 2017) |

The Karelian language is closely related to the Finnish language, and by some Finnish and Karelian linguists is viewed as a dialect of Finnish language. The biggest difference between the two languages is that while Finnish language borrowed many words from Swedish, the same happening with western Karelian dialects, eastern Karelian dialects borrowed many words from Russian, which leads to certain differences and difficulties in understanding one another. There are currently 7 different dialects of what can be classified as dialects of Karelian language: karelian proper, which is spoken in White Karelia in the Russian side of the border; livvi - a dialect spoken in Aunus (Olonets) Karelia. Lyydi - which is spoken in certain areas between Ladoga and Onega lakes.

Tver Karelian - the most archaic dialect spoken by descendants of Karelians that moved to mainland Russia after 1658, North and South Karelian dialects in Finland, which are often classified as dialects of Finnish language but the main difference being that they were developed and spoken by ethnic Karelians living on Karelian Isthmus and Ladoga Karelia; the same may be said stated about Savonian dialect, yet it has to be noted that it has originally been developed by Karelians who populated this area. As a significant effort was made in 19th century to develop a common Finnish language Savonian and North and South Karelian dialects are viewed as part of the Finnish language and other dialects are usually viewed as a distinct language.[21]

Religion

The majority of Russian Karelians are Eastern Orthodox Christians. The majority of Finnish Karelians are Lutherans.[citation needed]

Demographics

Significant enclaves of Karelians exist in the Tver oblast of Russia, resettled after Russia's defeat in 1617 against Sweden — in order to escape the peril of forced conversion to Lutheranism in Swedish Karelia. The Russians also promised tax deductions if the Orthodox Karelians migrated there. Olonets (Aunus) is the only city in Russia where the Karelians form a majority (60% of the population).

Karelians have been declining in numbers in modern times significantly due to a number of factors. These include low birthrates (characteristic of the region in general) and especially Russification, due to the predominance of Russian language and culture.

In 1926, according to the census, Karelians only accounted for 37.4% of the population in the Soviet Karelian Republic (which at that time did not yet include territories that would later be taken from Finland and added, most of which had mostly Karelian inhabitants), or 0.1 million Karelians. Russians, meanwhile, numbered 153,967 in Karelia, or 57.2% of the population.

By 2002, there were only 65,651 Karelians in the Republic of Karelia (65.1% of the number in 1926, including the Karelian regions taken from Finland which were not counted in 1926), and Karelians made up only 9.2% of the population in their homeland. Russians, meanwhile, were 76.6% of the population in Karelia. This trend continues to this day, and may cause the disappearance of Karelians as a distinct group.

See also

References

- ^ Minahan, James (2000). One Europe, Many Nations. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 368. ISBN 978-0-313-30984-7.

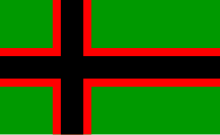

- ^ "The Flags of Karelia". Heninen.net. Retrieved 2017-03-12.

- ^ "Russian census of 2010" (XLS). Gks.ru. Retrieved 2017-03-12.

- ^ Languages of Finland. "Finland". Ethnologue.com. Retrieved 2017-03-12.

- ^ "Ethnic composition of Ukraine 2001". Pop-stat.mashke.org. Retrieved 2017-03-12.

- ^ [1][dead link]

- ^ "RAHVASTIK RAHVUSE, SOO JA ELUKOHA JÄRGI, 31. DETSEMBER 2011". Pub.stat.ee. Retrieved 2017-03-12.

- ^ Sögubrot af nokkurum fornkonungum í Dana- ok Svíaveldi

- ^ Hálfdanar saga Eysteinssonar

- ^ Saga Ólafs hins helga Haraldssonar

- ^ a b c The Chronicle of Duke Erik, Chapter 10-The founding of Stockholm

- ^ The Chronicle of Novgorod, 1016-1471

- ^ The Laurentian Chronicle

- ^ The Chronicle of Novgorod, 1016-1471

- ^ The Chronicle of Novgorod, 1016-1471

- ^ The Chronicle of Novgorod, 1016-1471

- ^ The Chronicle of Novgorod, 1016-1471

- ^ The Chronicle of Novgorod, 1016-1471

- ^ The Chronicle of Novgorod, 1016-1471

- ^ Barbara A. Anderson and Brian D. Silver, "Estimating Russification of Ethnic Identity among Non-Russians in the USSR," Demography 20 (November, 1983): 461-489.

- ^ [2][dead link]

External links

- Russian Karelians (The Peoples of the Red Book)

- Saimaa Canal links two Karelias (ThisisFINLAND from Ministry for Foreign Affairs)

- Tracing Finland's Eastern Border(ThisisFINLAND from Ministry for Foreign Affairs)

- Finno-Ugric media center