Ski jumping

Peter Prevc in Titisee-Neustadt, March 2016 | |

| Highest governing body | International Ski Federation (FIS) |

|---|---|

| First played | 22 November 1808 Olaf Rye, Eidsberg church, Eidsberg, Norway |

| Characteristics | |

| Team members | M Individual (50) L Individual (40) Team event (4) Super Team event (2) |

| Type | Nordic skiing |

| Equipment | Skis |

| Venue | Ski jumping hill |

| Presence | |

| Olympic | 1924 (men) 2014 (women) 2022 (mixed team) |

| World Championships | 1925 (men's nordic) 1972 (ski flying) 2009 (women's nordic) |

Ski jumping is a winter sport in which competitors aim to achieve the farthest jump after sliding down on their skis from a specially designed curved ramp. Along with jump length, competitor's aerial style and other factors also affect the final score. Ski jumping was first contested in Norway in the late 19th century, and later spread through Europe and North America in the early 20th century. Along with cross-country skiing, it constitutes the traditional group of Nordic skiing disciplines.[1]

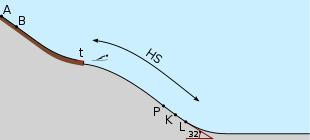

The ski jumping venue, commonly referred to as a hill, consists of the jumping ramp (in-run), take-off table, and a landing hill. Each jump is evaluated according to the distance covered and the style performed. The distance score is related to the construction point (also known as the K-point), which is a line drawn in the landing area and serves as a "target" for the competitors to reach.[2]

The score of each judge evaluating the style can reach a maximum of 20 points. The jumping technique has evolved over the years, from jumps with the skis parallel and both arms extended forward, to the "V-style", which is widely used today.

Ski jumping has been included at the Winter Olympics since 1924 and at the FIS Nordic World Ski Championships since 1925. Women's participation in the sport began in the 1990s, while the first women's event at the Olympics has been held in 2014. All major ski jumping competitions are organised by the International Ski Federation. Stefan Kraft holds the official record for the world's longest ski jump with 253.5 metres (832 ft), set on the ski flying hill in Vikersund in 2017.[3] Ski jumping can also be performed in the summer on an in-run where the tracks are made from porcelain and the grass on the slope is covered with water-soaked plastic. The highest level summer competition is the FIS Ski Jumping Grand Prix, contested since 1994.

History

[edit]Like most of the Nordic skiing disciplines, the first ski jumping competitions were held in Norway in the 19th century, although there is evidence of ski jumping in the late 18th century. The recorded origins of the first ski jump trace back to 1808, when Olaf Rye reached 9.5 m (31 ft). Sondre Norheim, who is regarded as the "father" of the modern ski jumping, won the first-ever ski jumping competition with prizes, which was held in Høydalsmo in 1866.

The first larger ski jumping competition was held on Husebyrennet hill in Oslo, Norway, in 1875. Due to its poor infrastructure and the weather conditions, in 1892 the event was moved to Holmenkollen, which is today still one of the main ski jumping events in the season.

In the late 19th century, Sondre Norheim and Nordic skier Karl Hovelsen immigrated to the United States and started developing the sport in that country. In 1924, ski jumping was featured at the 1924 Winter Olympics in Chamonix, France. The sport has been featured at every Olympics since.

Ski jumping was brought to Canada by Norwegian immigrant Nels Nelsen. Starting with his example in 1915 until late 1959, annual ski jumping competitions were held on Mount Revelstoke — the ski hill Nelsen designed — the longest period of any Canadian ski jumping venue. Revelstoke's was the biggest natural ski jump hill in Canada and internationally recognized as one of the best in North America. The length and natural grade of its 600 m (2,000 ft) hill made possible jumps of over 60 m (200 ft)—the longest in Canada. It was also the only hill in Canada where world ski jumping records were set, in 1916, 1921, 1925, 1932, and 1933.[4]

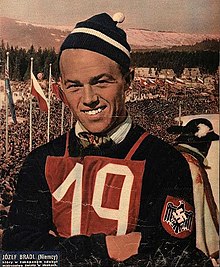

In 1935, the origins of ski flying began in Planica, Slovenia, where Josef Bradl became the first competitor in history to jump over 100 m (330 ft). At the same venue, the first official jump over 200 m (660 ft) was achieved in 1994, when Toni Nieminen landed at 203 meters.[5]

In 1964 in Zakopane, Poland, the large hill event was introduced at the FIS Nordic World Ski Championships. In the same year, the normal hill event was included on the Olympic programme at the 1964 Winter Olympics. The team event was added later, at the 1988 Winter Olympics.

Rules

[edit]Hills

[edit]

A ski jumping hill is typically built on a steep natural slope. It consists of the jumping ramp (in-run), take-off table, and a landing hill. Competitors glide down from a common point at the top of the in-run, achieving considerable speeds at the take-off table, where they take off, carried by their own momentum. While airborne, they maintain an aerodynamic position with their bodies and skis, which allows them to maximise the length of their jump. The landing slope is constructed so that the jumper's trajectory is near-parallel with it, and the athlete's relative height to the ground is gradually lost, allowing for a gentle and safe landing. The landing space is followed by an out-run, a substantial flat or counter-inclined area that permits the skier to safely slow down.[6] The out-run area is fenced and surrounded by a public auditorium.

The slopes are classified according to the distance that the competitors travel in the air, between the end of the table and the landing. Each hill has a construction point (K-point), which serves as a "target" that the competitors should reach. The classification of the hills are as follows:[7]

| Class | Construction point | Hill size |

|---|---|---|

| Small hill | to 45 meters | to 49 meters |

| Medium hill | 45–74 m | 50–84 m |

| Normal hill | 75–99 m | 85–109 m |

| Large hill | 100–130 m | 110–149 m |

| Giant hill | 131–169 m | 150–184 m |

| Ski flying hill | over 170 m | over 185 m |

Scoring system

[edit]Competitors are ranked according to a numerical score obtained by adding up components based on distance, style, inrun length (gate factor) and wind conditions. In the individual event, the scores from each skier's two competition jumps are combined to determine the winner.

Distance score depends on the hill's K-point. For K-90 and K-120 competitions, the K-point is set at 90 meters and 120 meters, respectively. Competitors are awarded 60 points (normal and large hills) and 120 points (flying hills) if they land on the K-point. For every meter beyond or below the K-point, extra points are awarded or deducted; the typical value is 2 points per meter in small hills, 1.8 points in large hills and 1.2 points in ski flying hills. A competitor's distance is measured between the takeoff and the point where the feet came in full contact with the landing slope (for abnormal landings, touchpoint of one foot, or another body part is considered). Jumps are measured with accuracy of 0.5 meters for all competitions.[8]: 64–65

During the competition, five judges are based in a tower to the side of the expected landing point. They can award up to 20 points each for jumping style, based on keeping the skis steady during flight, balance, optimal body position, and landing. The highest and lowest style scores are disregarded, with the remaining three scores added to the distance score.[9]

Gate and wind factors were introduced by the 2009 rules, to allow fairer comparison of results for a scoring compensation for variable outdoor conditions. Aerodynamics and take-off speed are important variables that affect the jump length, and if weather conditions change during a competition, the conditions will not be the same for all competitors. Gate factor is an adjustment made when the inrun (or start gate) length is adjusted from the initial position in order to provide optimal take-off speed. Since higher gates result in higher take-off speeds, and therefore present an advantage to competitors, points are subtracted when the starting gate is moved up, and added when the gate is lowered. An advanced calculation also determines compensation points for the actual unequal wind conditions at the time of the jump; when there is back wind, points are added, and when there is front wind, points are subtracted. Wind speed and direction are measured at five different points based on average value, which is determined before every competition.[10]

If two or more competitors finish the competition with the same number of points, they are given the same placing and receive same prizes.[7] Ski jumpers below the minimum safe body mass index are penalised with a shorter maximum ski length, reducing the aerodynamic lift they can achieve. These rules have been credited with stopping the most severe cases of underweight athletes, but some competitors still lose weight to maximise the distance they can achieve.[11] In order to prevent an unfair advantage due to a "sailing" effect of the ski jumping suit, material, thickness and relative size of the suit are regulated.[12]

Techniques

[edit]

Each jump is divided into four parts: in-run, take-off (jump), flight, and landing.

By using the V-style, firstly pioneered by Swedish ski jumper Jan Boklöv in the mid-1980s,[14] modern skiers are able to exceed the distance of the take-off hill by about 10% compared to the previous technique with parallel skis.[citation needed] Previous techniques included the Kongsberger technique, the Däescher technique and the Windisch technique.[14] Until the mid-1960s, the ski jumper came down the in-run of the hill with both arms pointing forwards. This changed when the Däscher technique was pioneered by Andreas Däscher in the 1950s, as a modification of the Kongsberger and Windisch techniques. A lesser-used technique as of 2017 is the H-style which is essentially a combination of the parallel and V-styles, in which the skis are spread very wide apart and held parallel in an "H" shape. It is prominently used by Domen Prevc.

Skiers are required to touch the ground in the Telemark landing style (Norwegian: telemarksnedslag), named after the Norwegian county of Telemark. This involves the landing with one foot in front of the other with knees slightly bent, mimicking the style of Telemark skiing. Failure to execute a Telemark landing leads to the deduction of style points, issued by the judges.[7][15]

Major competitions

[edit]All major ski jumping competitions are organised by the International Ski Federation.

The large hill ski jumping event was included at the Winter Olympic Games for the first time in 1924, and has been contested at every Winter Olympics since then.[16] The normal hill event was added in 1964. Since 1992, the normal hill event is contested at the K-90 size hill; previously, it was contested at the K-60 hill.[16] Women's debuted at the Winter Olympics in 2014.[17]

The FIS Ski Jumping World Cup has been contested since the 1979–80 season.[18] It runs between November and March every season, and consists of 25–30 competitions at most prestigious hills across Europe, United States and Japan. Competitors are awarded a fixed number of points in each event according to their ranking, and the overall winner is the one with most accumulated points. FIS Ski Flying World Cup is contested as a sub-event of the World Cup, and competitors collect only the points scored at ski flying hills from the calendar.

The ski jumping at the FIS Nordic World Ski Championships was first contested in 1925. The team event was introduced in 1982, while the women's event was first held in 2009.

The FIS Ski Flying World Championships was first contested in 1972 in Planica.[19]

The Four Hills Tournament has been contested since the 1952–53 season.[20] It is contested around the New Year's Day at four venues – two in Germany (Oberstdorf and Garmisch-Partenkirchen) and two in Austria (Innsbruck and Bischofshofen), which are also scored for the World Cup. Those events are traditionally held in a slightly different format than other World Cup events (first round is held as a knockout event between 25 pairs of jumpers), and the overall winner is determined by adding up individual scores from every jump.

Other competitions organised by the International Ski Federation include the FIS Ski Jumping Grand Prix (held in summer), Continental Cup, FIS Cup, FIS Race, and Alpen Cup.

Women's participation

[edit]In January 1863 in Trysil, Norway, at that time 16 years old Norwegian Ingrid Olsdatter Vestby, became the first-ever known female ski jumper, who participated in the competition. Her distance is not recorded.[21]

Women began competing at the high level since the 2004–05 Continental Cup season.[22] International Ski Federation organised three women's team events in this competition.

Women's made a premiere FIS Nordic World Ski Championships performance in 2009 in Liberec.[22] American ski jumper Lindsey Van became the first world champion.[23]

In the 2011–12 season, women competed for the first time in the World Cup. The first event was held on 3 December 2011 at Lysgårdsbakken at normal hill in Lillehammer, Norway. The first-ever female World Cup winner was Sarah Hendrickson,[24] who also became the inaugural women's World Cup overall champion.[25] Previously, women had only competed in Continental Cup seasons.

In the 2022-23 season, women competed for the first time ever in ski flying. The historic event was held in Vikersundbakken in Vikersund the 19th March 2023. It was won by Slovenian jumper Ema Klinec[26][27][28]

Olympic Games

[edit]In 2006, the International Ski Federation proposed that women could compete at the 2010 Winter Olympics,[29] but the proposal was rejected by the IOC because of the low number of athletes and participating countries at the time.[30]

A group of fifteen competitive female ski jumpers later filed a suit against the Vancouver Organizing Committee for the 2010 Olympic and Paralympic Winter Games on the grounds that it violated the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms since men were competing.[31] The suit failed, with the judge ruling that the situation was not governed by the charter.

A further milestone was reached when women's ski jumping was included as part of the 2014 Winter Olympics at normal hill event. The first Olympic champion was Carina Vogt.[17]

Record jumps

[edit]

Since 1936, when the first jump beyond 100 metres (330 ft) was made, all world records in the sport have been made in the discipline of ski flying. As of July 2024, the official world record for the longest ski jump is 253.5 m (832 ft), set by Stefan Kraft at Vikersundbakken in Vikersund, Norway. In a non-official event near Akureyri on Iceland, in April 2024 Ryōyū Kobayashi achieved a distance of 291 m (955 ft) after 10 seconds in the air and landing smoothly. It was an unofficial world record which is not being counted as a ski flying world record by the FIS.[32] In 2015 in Vikersund, Dimitry Vassiliev reached 254 m (833 ft) but fell upon landing; his jump is another unofficial record.[33]

Silje Opseth holds the women's world record at 230,5 metres (756 feet) which was set on 17th March 2024 in Vikersundbakken. [34]

The lists below show the progression of world records through history at 50-meter milestones. Only official results are listed, invalid jumps are not included.

Men

[edit]| First jump | Date | Country | Hill | Place | Meters | Yards | Feet | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| in history | 1808-11-22 | Olaf Rye | Eidsberg church | Eidsberg, Norway | 9.5 | 10.4 | 31 | |

| over 50 meters | 1913-02-16 | Ragnar Omtvedt | Curry Hill | Ironwood, Michigan, United States | 51.5 | 56.3 | 169 | |

| over 100 meters | 1936-03-15 | Sepp Bradl | Bloudkova velikanka | Planica, Kingdom of Yugoslavia | 101.5 | 111.0 | 340 | |

| over 150 meters | 1967-02-11 | Lars Grini | Heini-Klopfer-Skiflugschanze | Oberstdorf, West Germany | 150.0 | 164.0 | 492 | |

| over 200 meters | 1994-03-17 | Toni Nieminen | Velikanka bratov Gorišek | Planica, Slovenia | 203.0 | 222.0 | 666 | |

| over 250 meters | 2015-02-14 | Peter Prevc | Vikersundbakken | Vikersund, Norway | 250.0 | 273.4 | 820 |

Women

[edit]| First jump | Date | Country | Hill | Place | Meters | Yards | Feet | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| in history | 1863 | Ingrid Olsdatter Vestby | Nordbybakken | Trysil, Norway | unknown | |||

| over 50 meters | 1932 | Johanne Kolstad | Gråkallbakken | Trondheim, Norway | 62.0 | 67.8 | 203 | |

| over 100 meters | 1981-03-29 | Tiina Lehtola | Rukatunturi | Kuusamo, Finland | 110.0 | 120.3 | 361 | |

| over 150 meters | 1994-02-05 | Eva Ganster | Kulm | Tauplitz/Bad Mitterndorf, Austria | 161.0 | 176.1 | 528 | |

| over 200 meters | 2003-01-29 | Daniela Iraschko | Kulm | Tauplitz/Bad Mitterndorf, Austria | 200.0 | 218.7 | 656 | |

Tandem

[edit]| First jump | Date | Country | Hill | Place | Meters | Yards | Feet | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| in history[35] | 2016-02-18 | Rok Urbanc Jaka Rus |

Planica Nordic Center HS45 | Planica, Slovenia | 35.0 | 38.3 | 115 |

Perfect-score jumps

[edit]Those who have managed to show a perfect jump, which means that all five judges attributed the maximum style score of 20 points for their jumps. Kazuyoshi Funaki, Sven Hannawald and Wolfgang Loitzl were attributed 4x20 (plus another 19.5) style score points for their second jump, thus receiving nine times the maximum score of 20 points within one competition. Kazuyoshi Funaki is the only one in history who achieved this more than once. So far only seven jumpers are recorded to have achieved this score in total of ten times:

See also

[edit]- Ski flying

- Nordic combined

- List of FIS Nordic World Ski Championships medalists in ski jumping

- List of FIS Ski Jumping World Cup team events

- List of Olympic medalists in ski jumping

- List of Four Hills Tournament winners

- Medicinernes Skiklub Svartor

- FIS Ski Flying World Cup

References

[edit]- General

- "Ski Jumping History". olympic.org. Archived from the original on 14 August 2012. Retrieved 13 March 2017.

- "The history of ski jumping". skijumping-info.com. Archived from the original on 2 December 2014. Retrieved 13 March 2017.

- "Ski Jumping – History". abc-of-skiing.com. Archived from the original on 22 March 2016. Retrieved 19 March 2017.

- "Bakken - Ski Jumping Database". bakken-skijumping.com. Retrieved 30 November 2022.

- Specific

- ^ "The FIS Disciplines". International Ski Federation. June 2019. Retrieved January 8, 2022.

- ^ "Ski Jumping Winter Olympics Spectator's Guide by Ron Judd (13/12/2009)". The Seattle Times. Retrieved 18 May 2015.

- ^ "Kraft Sets World Record in Ski Jumping". U.S. News & World Report. 18 March 2017. Retrieved 18 March 2017.

- ^ "The History of Skiing on Mount Revelstoke". Archived from the original on 2017-10-18. Retrieved 2017-10-18.

- ^ "Letalnica, Planica". skisprungschanzen.com. Retrieved 13 March 2017.

- ^ "Standards for the Construction of Jumping Hills - 2012" (PDF). International Ski Federation. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2022-10-09. Retrieved 14 March 2017.

- ^ a b c "THE INTERNATIONAL SKI COMPETITION RULES (ICR)" (PDF). International Ski Federation. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2022-10-09. Retrieved 14 March 2017.

- ^ "The International Ski Competition Rules (ICR): Book III – Ski Jumping" (PDF). International Ski Federation. October 2017. Archived from the original (PDF) on 27 January 2018. Retrieved March 19, 2018.

- ^ Jim Pagels (17 February 2014). "Why Does Olympic Ski Jumping Need Judges?". theatlantic.com. Retrieved 14 March 2017.

- ^ "Ski Jumping 101". Women's Ski Jumping USA. Retrieved March 19, 2018.

- ^ Longman, Jeré (February 11, 2010). "For Ski Jumpers, a Sliding Scale of Weight, Distance and Health". The New York Times. Retrieved 11 February 2010.

- ^ "Ski jumping 101: Equipment". NBC Olympics. June 19, 2017. Retrieved 2017-09-14.

- ^ MacArthur, Paul J. (March–April 2011). Skiing Heritage Journal, p. 23, at Google Books. International Skiing History Association. Retrieved 22 May 2015.

- ^ a b "Development of ski jumping technique". skijumping-info.com. Archived from the original on 29 November 2014. Retrieved 15 January 2012.

- ^ Kunnskapsforlagets idrettsleksikon (Encyclopedia of Sports), Oslo: Kunnskapsforlaget, 1990. ISBN 82-573-0408-5

- ^ a b John Gettings; Christine Frantz. "Winter Olympics: Ski Jumping". infoplease.com. Retrieved 14 March 2017.

- ^ a b Rob Hodgetts (11 February 2014). "Sochi 2014: Carina Vogt wins women's ski jumping gold". BBC News. Retrieved 14 March 2017.

- ^ "Facts & Figures about the World Cup in Sapporo". International Ski Federation. 23 January 2014. Retrieved 14 March 2017.

- ^ "Planica – cradle of Slovenian sport". slovenia.si. Archived from the original on 2017-03-15. Retrieved 14 March 2017.

- ^ "All Winners". Four Hills Tournament.

- ^ Haarstad, Kjell (1993): Skisportens oppkomst i Norge. Trondheim: Tapir.

- ^ a b Matt Slater (2 March 2009). "Why it's time to let ladies fly". BBC News. Retrieved 14 March 2017.

- ^ (sta) (20 February 2009). "Liberec: Svetovna prvakinja v skoki Lindsey Van, Manja Pograjc zasedla 24. mesto" (in Slovenian). dnevnik.si. Retrieved 14 March 2017.

- ^ "Sarah Hendrickson, 17, wins ski jump". ESPN. 3 December 2001. Retrieved 14 March 2017.

- ^ Stefan Diaz; Egon Theiner (3 March 2012). "Zao: Sarah Hendrickson wins overall World Cup". ladies-skijumping.com. Retrieved 14 March 2017.

- ^ Christiansen, Anders K.; Boge-Fredriksen, Hans Christian (2022-04-13). "Historisk FIS-vedtak: Kvinner får delta i skiflyging: – Bobler over av glede". VG (in Norwegian Bokmål). Retrieved 2023-03-18.

- ^ Lokøy, Christian Dehlie (2023-03-18). "Hoppkvinnene skrev historie: – Det var helt magisk". NRK (in Norwegian Bokmål). Retrieved 2023-03-18.

- ^ Baardsen, Joachim; Arnesen Strømshoved, Kristian (2023-03-19). "Klinec med verdensrekord – Opseth på pallen i historisk renn". VG (in Norwegian Bokmål). Retrieved 2023-03-19.

- ^ "FIS MEDIA INFO: Decisions of the 45th International Ski Congress in Vilamoura/Algarve". International Ski Federation. Archived from the original on 23 January 2013. Retrieved 14 November 2009.

- ^ "IOC approves skicross; rejects women's ski jumping". iht.com. Retrieved 15 March 2009.

- ^ "Why women can't ski jump in the Winter Olympics". Christian Science Monitor. Retrieved 14 November 2014.

- ^ Ryoyu Kobayashi flies 291 meter FIS

- ^ Eurosport (15 February 2015). "Ski jump world record broken for second time in two days as Anders Fannemel flies to glory". Archived from the original on 17 February 2015. Retrieved 15 February 2015.

- ^ Nessler, Simon Zetlitz (2024-03-17). "Satte verdensrekord etter blodig fall: – Tidenes berg-og-dal-bane". NRK (in Norwegian Bokmål). Retrieved 2024-03-26.

- ^ A. V. (22 February 2016). "Rok Urbanc in Jaka Rus izvedla prvi smučarski skok v tandemu (VIDEO)" (in Slovenian). Delo. Retrieved 15 March 2017.