Lost in Translation (film)

| Lost in Translation | |

|---|---|

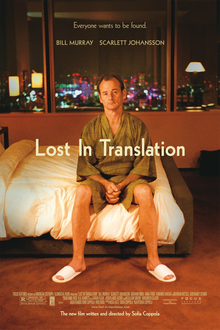

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Sofia Coppola |

| Written by | Sofia Coppola |

| Produced by | Sofia Coppola Ross Katz |

| Starring | Bill Murray Scarlett Johansson Giovanni Ribisi Anna Faris Fumihiro Hayashi |

| Cinematography | Lance Acord |

| Edited by | Sarah Flack |

| Music by | Brian Reitzell Kevin Shields Roger Joseph Manning Jr. Air |

Production companies | |

| Distributed by | Focus Features (US) Pathé (France) Constantin Film (Germany) Momentum Pictures (UK) |

Release dates |

|

Running time | 101 minutes[2] |

| Country | United States[1] |

| Languages | English Japanese |

| Budget | $4 million[3] |

| Box office | $119.7 million[3] |

Lost in Translation is a 2003 American romantic comedy-drama film written and directed by Sofia Coppola. It was her second feature film after The Virgin Suicides (1999). It stars Bill Murray as aging actor Bob Harris, who befriends college graduate Charlotte (Scarlett Johansson) in a Tokyo hotel.

Lost in Translation received critical acclaim and was nominated for four Academy Awards, including Best Picture, Best Actor for Bill Murray, and Best Director for Coppola; Coppola won for Best Original Screenplay. Murray and Johansson each won a BAFTA award for Best Actor in a Leading Role and Best Actress in a Leading Role respectively. The film was a commercial success, grossing $119 million on a budget of $4 million.

Plot

Bob Harris, an aging American movie star, arrives in Tokyo to film an advertisement for Suntory whisky. Charlotte, a young college graduate, is left in her hotel room by her husband, John, a celebrity photographer on assignment in Tokyo. Charlotte is unsure of her future with John, feeling detached from his lifestyle and dispassionate about their relationship. Bob's own 25-year marriage is tired as he goes through a midlife crisis.

Each day Bob and Charlotte encounter each other in the hotel, and finally meet at the hotel bar one night when neither can sleep. Eventually Charlotte invites Bob to meet with some local friends of hers. The two bond through a memorable night in Tokyo, welcomed without prejudice by Charlotte's friends and experiencing Japanese nightlife and culture. In the days that follow, Bob and Charlotte's platonic relationship develops as they spend more time together. One night, each unable to sleep, the two share an intimate conversation about Charlotte's personal troubles and Bob's married life.

On the penultimate night of his stay, Bob sleeps with the hotel bar's female jazz singer. The next morning Charlotte arrives at his room to invite him for lunch and overhears the woman in his room, leading to an argument over lunch. Later that night, during a fire alarm at the hotel, Bob and Charlotte reconcile and express how they will miss each other as they make a final visit to the hotel bar.

The following morning, Bob is set to return to the United States. He tells Charlotte goodbye at the hotel lobby and watches her walk back to the elevator. In a taxi to the airport, Bob sees Charlotte on a crowded street and gets out and goes to her. He embraces the tearful Charlotte and whispers something in her ear. The two share a kiss, say goodbye and Bob departs.

Cast

- Bill Murray as Bob Harris

- Scarlett Johansson as Charlotte

- Giovanni Ribisi as John

- Anna Faris as Kelly

- Fumihiro Hayashi as Charlie Brown

- Akiko Takeshita as Ms. Kawasaki

- François Du Bois as the Pianist

- Takashi Fujii as TV host

- Hiromix as herself

Analysis

Over the course of the film, several things are "lost in translation".[4] Bob (Murray), a Japanese director (Yutaka Tadokoro), and an interpreter (Takeshita) are on a set, filming a commercial for Suntory whisky (specifically, 17-year-old Hibiki). In several exchanges, the director gives lengthy, impassioned directives in Japanese. These are invariably followed by brief, incomplete translations from the interpreter.

Director [in Japanese, to the interpreter]: The translation is very important, O.K.? The translation.

Interpreter [in Japanese, to the director]: Yes, of course. I understand.

Director [in Japanese, to Bob]: Mr. Bob. You are sitting quietly in your study. And then there is a bottle of Suntory whisky on top of the table. You understand, right? With wholehearted feeling, slowly, look at the camera, tenderly, and as if you are meeting old friends, say the words. As if you are Bogie in Casablanca, saying, "Here's looking at you, kid,"—Suntory time!

Interpreter [In English, to Bob]: He wants you to turn, look in camera. O.K.?

Bob: ...Is that all he said?[5]

In addition to the meaning and detail lost in the translation of the director's words, the two central characters in the film—Bob and Charlotte—are also lost in other ways. On a basic level, they are lost in the alien Japanese culture. But in addition, they are lost in their own lives and relationships, a feeling, amplified by their displaced location, that leads to their blossoming friendship and growing connection with one another.[6]

By her own admission, Coppola wanted to create a romantic movie about two characters that have a moment of connection. The story's timeline was intentionally shortened to emphasize this moment.[7] Additionally, Coppola has said that since "there's not much happening in the story besides [Bob and Charlotte's relationship]", the filmmakers tried to keep an ongoing tension.[8]

"As an actor, and as a writer/director, the question is: is it going to be very noble here? [Is] this guy going to say, “I just can’t call you. We can’t share room service anymore?” Is it going to be like that sort of thing, or is it going to be a little more real where they actually get really close to it?"

—Bill Murray[9]

Murray has described his biggest challenge in portraying Bob as managing the character's conflicted feelings. On one hand, Murray said, Bob knows that it could be dangerous to become too close to Charlotte, but on the other, he is lonely and knows that having an affair would be easy. Murray worked to portray a balance between being affectionate and being "respectable".[9]

The academic Marco Abel lists Lost in Translation as one of many films that belong to the category of "postromance" cinema, which he says offers a negative perspective of love, sex, romance, and dating. According to Abel, the characters in such films reject the idealized notion of lifelong monogamy.[10]

The author and filmmaker Anita Schillhorn van Veen interprets the film as a criticism of modernity, in which Tokyo is a contemporary "floating world" of fleeting pleasures that are too alienating and amoral to facilitate meaningful relationships.[11] Tessa Dwyer, writing for Linguistica Antverpiensia, New Series – Themes in Translation Studies, called Lost in Translation a polyglot film that challenges the film industry's "more usual tendency to ignore or deny issues of language difference" by highlighting Bob and Charlotte's difficult contact with the Japanese language.[12]

Aesthetics

The author and lecturer Maria San Filippo contends that the film's setting, Tokyo, is an audiovisual metaphor for Bob and Charlotte's world views. She explains that the calm ambience of the city's hotel represents Bob's desire to be secure and undisturbed, while the energetic atmosphere of the city streets represents Charlotte's willingness to engage with the world.[13] Coppola and Acord, the film's cinematographer, agreed that Lost in Translation needed to rely heavily on visual expression to support the characters' romance.

Robert Hahn, an essayist writing for The Southern Review, suggested that the filmmakers deliberately used chiaroscuro, the art of using strong contrasts between light and dark to support the story. He wrote that the film's dominant light tones symbolize feelings of humor and romance, and they are contrasted with dark tones that symbolize underlying feelings of despondency. He compared this to the technique of the painter John Singer Sargent.[14]

The film's opening shot, which features a close shot of Charlotte resting in transparent pink underwear, has interested various commentators. In particular, it has been compared to the portraitures of the painter John Kacere and the image of Brigitte Bardot in the opening scene of the 1963 film Contempt. Dwyer wrote that when the two shots are compared, they reveal the importance of language difference, as both films highlight the complexities involved with characters speaking multiple languages.[12] Filippo wrote that while the image in Contempt is used to remark on sexual objectification, Coppola "doesn't seem to be making a statement at all beyond a sort of endorsement of beauty for beauty's sake".[15]

Coppola revealed in a 2013 interview that the shot is indeed based on the art of Kacere.[16] Geoff King, a professor of film at Brunel University, contends that the shot is marked by an "obvious" appeal in its potential eroticism, and a "subtle" appeal in its artistic qualities. He used the shot as an example of the film's obvious attractions, which are characteristic of mainstream film, and its subtle ones, which are typified by "indie" film.[17]

Production

Development

"I remember having these weeks there that were sort of enchanting and weird ... Tokyo is so disorienting, and there's a loneliness and isolation. Everything is so crazy, and the jet lag is torture. I liked the idea of juxtaposing a midlife crisis with that time in your early 20s when you're, like, What should I do with my life?"

—Sofia Coppola, 2003[18]

Coppola devised the idea of Lost in Translation after many visits to Tokyo in her twenties, basing much of the story on her experiences there.[16][19][20] Coppola was attracted to the neon lights of Tokyo and has described the Park Hyatt Tokyo, where most of the film's interior sequences take place, as one of her "favorite places in the world".[19] Particularly, she was attracted to its quietness, design, and "combination of different cultures", which include a New York bar and French restaurant.[19]

Coppola spent six months writing the film, beginning with "short stories" and "impressions" that culminated into a 70-page script.[21][22] She wanted to create a story that was "a little more funny and romantic" than her previous feature, The Virgin Suicides, and she spent little time planning or rewriting it.[8][23] Coppola has called the film a "valentine" to Tokyo,[24] in which she has displayed the city in the way that it is meaningful to her.

Coppola wrote the film with Murray in mind and said she would not have made it without him.[16] She said that she had always wanted to work with Murray and that she was attracted to his "sweet, lovable side".[19] She pursued him for five months to a year, relentlessly sending telephone messages and letters.[16][18][25] She enlisted help from Wes Anderson, who had directed Murray in two films, and screenwriter Mitch Glazer, who was a mutual friend.[22][25] In July 2002, Coppola and Murray finally met in a restaurant, and he agreed to participate because he "couldn't let her down".[25]

Despite this, Murray did not sign a contract; when he finally arrived in Tokyo, Coppola described it as "a huge relief".[26] Coppola first noticed Scarlett Johansson in Manny & Lo, where she related to her "understated" and "subtle" demeanor,[22][27] envisioning her as a "young Lauren Bacall-type girl".[16] Johansson, who was 17 years old at the time, immediately accepted the part and Coppola was happy with the maturity she brought to the character.[25][27] In writing the story, Coppola said she was influenced by the relationship between Humphrey Bogart and Lauren Bacall in Howard Hawks’ The Big Sleep.[22] Murray and Johansson did not do any auditions before filming.[16]

Filming

Lance Acord, the film's director of photography, has written that the cinematographic style of Lost in Translation is largely based on "daily experiences, memories and impressions" of his time in Japan.[28] He worked closely with Coppola to visualize the film, relying on multiple experiences he shared with her in Tokyo before production took place. Location scouting was carried out by Coppola, Acord, and Katz; and Coppola created 40 pages of photographs for the crew so that they would understand her visual intentions.[29]

Acord sought to maximize available light during shooting and use artificial lights as little as possible. He described this approach as conservative compared to "the more conventional Hollywood system", for which some of the crew's Japanese electricians thought he was "out of his mind".[30] In particular, Acord did not use any artificial lights to photograph the film's night-time exteriors.[30] Lost in Translation was largely shot in an improvised, "free-form" manner, which Coppola described as "stealthy" and "almost documentary-style".[19][31] The crew shot in some locations without permits, including Tokyo's subways and Shibuya Crossing; they avoided police by keeping a minimal crew.[20] Acord avoided grandiose camera movements in favor of still shots to avoid taking away from the loneliness of the characters.[30]

Most of the film was shot on an Aaton camera with 35 mm film stock, using Kodak Vision 500T 5263 stock for nightlight exteriors and Kodak Vision 320T 5277 stock in daylight. A smaller Moviecam Compact was used in confined locations. Coppola said that her father, Francis Ford Coppola, tried to convince her to shoot on video, but she ultimately decided on film, describing its “fragmented, dislocated, melancholic, romantic feeling", in contrast with video, which is "more immediate, in the present".[22] In interviews, she said she wanted to shoot Tokyo with a spontaneous "informality", similar to the "way a snapshot looks", and she chose to shoot on high-speed film stocks to evoke a "homemade intimacy".[18][20][22] Some scenes were shot wholly for mood and were captured without sound.[18]

Lost in Translation was shot six days per week in September and October 2002, over the course of 27 days.[18] During this time, videotape footage was mailed to editor Sarah Flack in New York City, where she began editing the film in a Red Car office.[32] The scenes with Bob and Charlotte together were largely shot in order.[33] Many of the interior scenes were shot overnight, because the hotel did not allow the crew to shoot in much of its public space until after 1 a.m.[30]

Various locations were used during production; in particular, the bar featured prominently in the film is the New York Bar, which is situated on the 52nd floor of the Shinjuku Park Tower and part of the Park Hyatt in Shinjuku, Tokyo. Other locations include the Heian Jingu shrine in Kyoto and the steps of the San-mon gate at Nanzen-ji, as well as the club Air in the Daikanyama district of Tokyo. All of the locations mentioned in the film are the names of actual places that existed in Tokyo at the time of filming. Murray described the first few weeks of the shoot as like "being held prisoner", since he was affected by jet lag, and Johansson said the shoot made her "busy, vulnerable and tired".[34][35]

Coppola spoke of the challenges of directing the movie with a Japanese crew, since she had to rely on her assistant director to make translations.[19] Much of the performances were improvised, and Coppola openly allowed modifications to dialogue during shooting. For example, the dialogue in the scene with Harris and the still photographer was unrehearsed.[36] Coppola has said that she was attracted to the idea of Bob and Charlotte going through stages of a romantic relationship all in one week — in which they have met, courted, hurt each other, and discussed intimate life. To conclude this relationship, Coppola wanted a special ending even though she thought the concluding scene in the script was mundane. Coppola instructed Murray to perform the kiss in that scene without telling Johansson, to which she reacted without preparation. The whisper was also unscripted, but too quiet to be recorded. While Coppola initially considered having audible dialogue dubbed into the moment, she later decided that it was better to keep it "between the two of them."[37]

After filming, Coppola and Flack spent approximately 10 weeks editing the film.[32] In the bonus features of the film's DVD, Murray called Lost in Translation his favorite film that he has worked on,[31] and Coppola described the film as her most "personal", since much of the story is based on her own experiences.[16] For example, Charlotte's relationship with her husband is based on Coppola's relationship with her husband when she first married, and the "Suntory" commercial is based on a commercial Coppola's father, Francis Ford Coppola, shot with Akira Kurosawa.[16]

Music

The film's soundtrack, supervised by Brian Reitzell, was released on September 9, 2003 by Emperor Norton Records. It contains five songs by Kevin Shields, including one from his group My Bloody Valentine. Coppola said much of the soundtrack consisted of songs that she "liked and had been listening to", and she worked with Reitzell to make Tokyo dream pop mixes.[16] The soundtrack also included The Jesus and Mary Chain hit "Just Like Honey". Allmusic gave the soundtrack four out of five stars, saying "Coppola's impressionistic romance Lost in Translation features an equally impressionistic and romantic soundtrack that plays almost as big a role in the film as Bill Murray and Scarlett Johansson do."[38]

Agathi Glezakos, an academic writing a review of Lost in Translation shortly after its release, wrote that the music in the film's karaoke scene constitutes a common "language" that allows Bob and Charlotte to connect with some of the Japanese people amidst their alienation.[39] In that scene, the rendition of the Pretenders' "Brass in Pocket" was selected to showcase a lively side of Charlotte, and "(What's So Funny 'Bout) Peace, Love, and Understanding" was chosen to establish that Bob is from a different generation. Both Coppola and Murray finally selected Roxy Music's "More Than This" during the shoot itself because they liked the band and thought the lyrics fit the story.[40]

Reception

Box office

Lost in Translation was screened at the 2003 Telluride Film Festival.[41] It was given a limited release on September 12, 2003 in 23 theaters where it grossed $925,087 on its opening weekend with an average of $40,221 per theater and ranking 15th at the box office.[3][42] It was given a wider release on October 3, 2003 in 864 theaters where it grossed $4,163,333 with an average of $4,818 per theater and ranking 7th. The film went on to make $44,585,453 in North America and $75,138,403 in the rest of the world for a worldwide total of $119,723,856.[3]

Critical response

Lost in Translation received critical acclaim, particularly for Coppola's direction and Murray and Johansson's performances. It has a score of 95% on Rotten Tomatoes, with an average rating of 8.4 out of 10 based on 222 reviews. The site's "critical consensus" states: "Effectively balancing humor and subtle pathos, Sofia Coppola crafts a moving, melancholy story that serves as a showcase for both Bill Murray and Scarlett Johansson".[43] The film also holds a score of 89 out of 100 based on 43 reviews on Metacritic, indicating "universal acclaim".[44]

Critic Roger Ebert gave Lost in Translation four out of four stars and named it the second best film of the year, describing it as "sweet and sad at the same time as it is sardonic and funny".[45] In his review for The New York Times, Elvis Mitchell wrote: "At 18, [Johansson] gets away with playing a 25-year-old woman by using her husky voice to test the level of acidity in the air ... Ms. Johansson is not nearly as accomplished a performer as Mr. Murray, but Ms. Coppola gets around this by using Charlotte's simplicity and curiosity as keys to her character."[46] Entertainment Weekly gave the film an "A" rating and Lisa Schwarzbaum wrote: "Working opposite the embracing, restful serenity of Johansson, Murray reveals something more commanding in his repose than we have ever seen before. Trimmed to a newly muscular, rangy handsomeness and in complete rapport with his character's hard-earned acceptance of life's limitations, Murray turns in a great performance."[47]

In his review for The New York Observer, Andrew Sarris called the film "that rarity of rarities, a grown-up romance based on the deliberate repression of sexual gratification ... when independent films are exploding with erotic images edging ever closer to outright pornography, Ms. Coppola and her colleagues have replaced sexual facility with emotional longing, without being too coy or self-congratulatory in the process."[48] USA Today gave the film three and a half stars out of four and wrote that it "offers quiet humor in lieu of the bludgeoning direct assaults most comedies these days inflict".[49] Time's Richard Corliss praised Murray's performance: "You won't find a subtler, funnier or more poignant performance this year than this quietly astonishing turn."[50] His performance has been likened to the sardonic persona of W. C. Fields.[6][51]

In his review for The Observer, Philip French wrote: "While Lost in Translation is deeply sad and has a strongly Antonioniesque flavour, it's also a wispy romantic comedy with little plot and some well-observed comic moments."[52] In The Guardian, Joe Queenan praised Coppola's film as "one of the few Hollywood films I have seen this year that has a brain; but more than that, it has a soul."[53]Rolling Stone's Peter Travers gave it four out of four stars and wrote: "Before saying goodbye, they whisper something to each other that the audience can't hear. Coppola keeps her film as hushed and intimate as that whisper. Lost in Translation is found gold. Funny how a wisp of a movie from a wisp of a girl can wipe you out."[54] J. Hoberman, in his review for the Village Voice, wrote: "Lost in Translation is as bittersweet a brief encounter as any in American movies since Richard Linklater's equally romantic Before Sunrise. But Lost in Translation is the more poignant reverie. Coppola evokes the emotional intensity of a one-night stand far from home—but what she really gets is the magic of movies".[55]

The Los Angeles Film Critics Association and National Society of Film Critics voted Bill Murray best actor of the year.[56][57] The New York Film Critics Circle also voted Murray best actor and Sofia Coppola best director.[58] Coppola received an award for special filmmaking achievement from the National Board of Review.[59] Lost in Translation also appeared on several critics' top ten lists for 2003.[60]Roger Ebert added it to his "great movies" list on his website.[61] Paste Magazine named it one of the 50 Best Movies of the Decade (2000-2009), ranking it at #7.[62] Entertainment Weekly named it one of the best films of the decade, writing: "Six years later, we still have no clue what Bill Murray whispered into Scarlett Johansson's ear. And we don't want to. Why spoil a perfect film?"[63]

Criticism

The film received some negative reviews, many from Japanese critics. Japanese TV critic Osugi of Osugi and Piko fame said "The core story is cute and not bad; however, the depiction of Japanese people is terrible!" [64] In a Guardian article about the film, Kiku Day, a musician specializing in the shakuhachi Japanese flute, wrote that she "couldn't help wondering not only whether I had watched a different movie, but whether the plaudits had come from a parallel universe of values"; according to Day, there is "no scene where the Japanese are afforded a shred of dignity. The viewer is sledgehammered into laughing at these small, yellow people and their funny ways."[65] Day also said "while shoe-horning every possible caricature of modern Japan into her movie, Coppola is respectful of ancient Japan. It is depicted approvingly, though ancient traditions have very little to do with the contemporary Japanese. The good Japan, according to this director, is Buddhist monks chanting, ancient temples, flower arrangement; meanwhile she portrays the contemporary Japanese as ridiculous people who have lost contact with their own culture."[65]

Hawaiian filmmaker and author E. Koohan Paik wrote that "The Japanese are presented not as people, but as clowns" and that "Lost in Translation relies wholly on the "otherness" of the Japanese to give meaning to its protagonists, shape to it plot, and color to its scenery. The inaccessibility of Japan functions as an extension of the alienation and loneliness Bob and Charlotte feel in their personal lives, thus laying the perfect conditions for romance to germinate: they're the only ones who understand each other. Take away the cartooniness of the Japanese and the humor falls flat, the main characters' intense yearning is neutralized and the plot evaporates."[66]

In another Guardian article, journalist David Stubbs described Lost in Translation as "mopey, self-pitying drivel", and its characters as "spoiled, bored, rich, utterly unsympathetic Americans".[67] In an article published in a 2004 issue of Maclean's, Steve Burgess criticized the film as an ethnocentric "compendium of unpleasant stereotypes ... indicative of the way visitors and foreign workers often view Japan."[68] Robin Antepara, an educator writing for an issue of Commonweal, wrote that while the story embodies stereotypes, "Charlotte is the personification of Japanese watchfulness," an often neglected virtue.[69] Respected critic Calen Cole also lamented the film's particularly meandering quality, noting that "it has a habit of lulling the viewer into a prescribed, choreographed sense of languor." Nevertheless, he applauded the film as being "classic," and said that he still "liked it." The academic Maria San Fillipino wrote that the "retreat into America-centrism would be disappointing if, again, it were not so truthful ... Coppola knows firsthand that American tourists rarely get to know any Japanese well enough to discover their depth as sympathetic human beings."[15] Katz responded to some of the criticism by saying "Sofia's love of Japan and love of the people that she's met there is incredibly evident in the film... Literally, we recounted experiences that I think all of us had gone through," and that none of the scenes were "any slight to Japanese people."[70]

Accolades

Lost in Translation won an Oscar for Best Original Screenplay in 2003.[71][72] It was also nominated for Best Director and Best Picture, but lost both to The Lord of the Rings: The Return of the King. Bill Murray was also nominated for Best Actor, but lost to Sean Penn for Mystic River.

The film won Golden Globes for Best Musical or Comedy Motion Picture, Best Screenplay, and Best Musical or Comedy Actor. It was also nominated for Best Director, and Best Musical or Comedy Actress.[73]

At the BAFTA film awards, Lost in Translation won the Best Editing, Best Actor and Best Actress awards. It was also nominated for best film, director, original screenplay, music and cinematography. It won four IFP Independent Spirit Awards, for Best Feature, Director, Male Lead, and Screenplay.[74] The film was honored with the original screenplay award from the Writers Guild of America.[75]

Release

Lost in Translation was released on DVD on February 3, 2004.[44][76] Entertainment Weekly gave it an "A" rating and criticized "the disc's slim bonus features", but praised the film for standing "on its own as a valentine to the mysteries of attraction".[77]

Lost in Translation was also released in high definition on the now defunct HD DVD format. A Blu-ray edition was released on January 4, 2011.[78]

References

- ^ "Lost in Translation". Allmovie. Retrieved 2015-03-14.

- ^ "Lost in Translation". Australian Classification. Retrieved 2015-03-14.

- ^ a b c d "Lost in Translation". Box Office Mojo. Retrieved 2009-03-13.

- ^ Rich, Motoko (2003-09-21). "What Else Was Lost in Translation". The New York Times. Retrieved 2012-05-02.

It doesn't take much to figure out that "Lost in Translation," the title of Sofia Coppola's elegiac new film about two lonely American souls in Tokyo, means more than one thing. There is the cultural dislocation felt by Bob Harris (Bill Murray), a washed-up movie actor, and Charlotte (Scarlett Johansson), a young wife trying to find herself. They are also lost in their marriages, lost in their lives. As Charlotte says, "I just feel so alone, even with people around." Then, of course, there is the simple matter of language.

- ^ Rich, Motoko (2003-09-21). "What Else Was Lost in Translation". The New York Times. Retrieved 2007-11-04.

- ^ a b Gehring, Wes D. (January 2004). "Along Comes Another Coppola". USA Today. 132. The Society for the Advancement of Education: 59. ISSN 0161-7389.

- ^ "The Co-Conspirators". Interview. 33 (9). New York: Interview, Inc.: 56 October 2003. ISSN 0149-8932.

- ^ a b Carter, Kelly (21 September 2003). "Famous lost words". South China Morning Post.

{{cite news}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help) - ^ a b Murray, Rebecca. "Interview with "Lost in Translation" Star Bill Murray". About.com. p. 1. Retrieved Feb 19, 2014.

- ^ Abel, Marco (2010). "Failing to Connect: Itinerations of Desire in Oskar Roehler's Postromance Films". New German Critique. 109. 37 (1). New German Critique, Inc.: 77. doi:10.1215/0094033X-2009-018.

- ^ Schillhorn van Veen, Anita (1 March 2006). "The Floating World: Representations of Japan in Lost in Translation and Demonlover". Asian Cinema. 17 (1): 190–193. ISSN 1059-440X.

- ^ a b Dwyer, Tessa (2005). "Universally speaking: Lost in Translation and polyglot cinema". Linguistica Antverpiensia, New Series – Themes in Translation Studies (4). Department of Translators and Interpreters, Artwerp University: 297–300.

{{cite journal}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help) - ^ San Filippo, Maria (2003). "Lost in Translation". Cineaste. 29 (1). New York: Cineaste: 28. ISSN 0009-7004.

- ^ Hahn, Robert (2006). "Dancing in the Dark". The Southern Review. 42 (1): 153–154. ISSN 0038-4534.

- ^ a b San Filippo, Maria (2003). "Lost in Translation". Cineaste. 29 (1). New York: Cineaste: 26. ISSN 0009-7004.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Stern, Marlow (Sep 12, 2013). "Sofia Coppola Discusses 'Lost in Translation' on Its 10th Anniversary". The Daily Beast. Retrieved Feb 20, 2014.

- ^ King, Geoff (2010). "Introduction". In Gary Needham and Yannis Tzioumakis (ed.). Lost in Translation. American Indies. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press. pp. 1–2. ISBN 9780748637461.

{{cite book}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help) - ^ a b c d e Betts, Kate (2003-09-15). "Sofia's Choice". TIME. Retrieved 2012-04-07.

- ^ a b c d e f "Sofia Coppola Talks About "Lost In Translation," Her Love Story That's Not "Nerdy" | Filmmakers, Film Industry, Film Festivals, Awards & Movie Reviews". Indiewire. 2011-11-08. Retrieved 2012-04-07.

- ^ a b c Archived 2011-07-24 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Sofia Coppola on LOST IN TRANSLATION". Screenwritersutopia.com. 2004-03-11. Retrieved 2012-04-07.

- ^ a b c d e f "Sofia Coppola's Lost in Translation - Filmmaker Magazine - Fall 2003". Filmmaker Magazine. Retrieved 2012-04-07.

- ^ Chumo, Peter N. II (January–February 2004). "Sofia Coppola". Creative Screenwriting. 11 (1): 58. ISSN 1084-8665.

- ^ Calhoun, Dave (2003). "Watching Bill Murray Movies". Another Magazine (5). Dazed Group: 100.

- ^ a b c d Hirschberg, Lynn (2003-08-31). "The Coppola Smart Mob". NYTimes.com. Retrieved 2012-04-07.

- ^ "26 EL1110 WLWIHSofia 001". Elle.com. 2010-10-07. Retrieved 2012-04-07.

- ^ a b Interview with Sofia Coppola - Lost in Translation Movie, Page 2

- ^ Acord, Lance (January 2004). "Channeling Tokyo for Lost in Translation". American Cinematographer. 85 (1). American Society of Cinematographers: 123–124. ISSN 0002-7928.

- ^ Chumo, Peter N. II (January–February 2004). "Sofia Coppola". Creative Screenwriting. 11 (1): 57. ISSN 1084-8665.

- ^ a b c d Alex Ballinger (12 October 2004). New Cinematographers. Laurence King Publishing. ISBN 978-1-85669-334-9. Retrieved 6 April 2012.

- ^ a b Lost in Translation (DVD). Focus Features/Universal Studios. 2004.

- ^ a b Crabtree, Sheigh (10 September 2003). "Editor Flack in Fashion for Coppola's "Lost" Pic". The Hollywood Reporter.

- ^ Chumo, Peter N. II (January–February 2004). "Sofia Coppola". Creative Screenwriting. 11 (1): 64. ISSN 1084-8665.

- ^ MacNab, Geoffrey (2004-01-01). "Geoffrey Macnab talks to Bill Murray". The Guardian. London.

- ^ Vernon, Polly (2004-01-05). "Polly Vernon meets Scarlett Johansson". The Guardian. London.

- ^ Chumo, Peter N. II (January–February 2004). "Sofia Coppola". Creative Screenwriting. 11 (1): 58–59. ISSN 1084-8665.

- ^ Chumo, Peter N. II (January–February 2004). "Sofia Coppola". Creative Screenwriting. 11 (1): 63–64. ISSN 1084-8665.

- ^ Phares, Heather. "Lost in Translation – Original Soundtrack". Allmusic. Rovi Corporation. Retrieved 2010-10-10.

- ^ Glezakos, Agathi (15 October 2003). "Movie Review: Lost in Translation". Reflections: Narratives of Professional Helping. 9 (4). California State University, Long Beach: 71–72. ISSN 1080-0220.

- ^ Chumo, Peter N. II (January–February 2004). "Sofia Coppola". Creative Screenwriting. 11 (1): 60–61. ISSN 1084-8665.

- ^ Mitchell, Elvis (September 1, 2003). "Telluride Marks Its 30th Year With a Passing of Torches". The New York Times. Retrieved 2009-03-25.

- ^ "Lost in Translation - Box Office Data, Movie News, Cast Information". The Numbers. Retrieved 2011-02-19.

- ^ "Lost in Translation". Rotten Tomatoes. Retrieved 2010-03-19.

- ^ a b "Lost in Translation". Metacritic. Retrieved 2011-05-25.

- ^ Ebert, Roger (September 12, 2003). "Lost in Translation". Chicago Sun-Times. Retrieved 2009-03-16.

- ^ Mitchell, Elvis (September 12, 2003). "An American in Japan, Making a Connection". The New York Times. Retrieved 2009-03-16.

- ^ Schwarzbaum, Lisa (September 10, 2003). "Lost in Translation". Entertainment Weekly. Retrieved 2009-03-16.

- ^ Sarris, Andrew (September 28, 2003). "Lonely Souls in a Strange Land: Lost in Translation Maps the Way". New York Observer. Retrieved 2009-03-16.

- ^ Clark, Mike (September 12, 2003). "Comedy doesn't get lost in Translation". USA Today. Retrieved 2009-03-16.

- ^ Corliss, Richard (September 15, 2003). "A Victory for Lonely Hearts". Time. Retrieved 2009-03-16.

- ^ Alleva, Richard (5 December 2003). "About a Boy: Kill Bill-Volume 1 and Lost in Translation". Commonweal. 130 (21). Commonweal Foundation: 14. ISSN 0010-3330.

- ^ French, Philip (January 11, 2004). "The odd Coppola". The Observer. London. Retrieved 2009-03-16.

- ^ Queenan, Joe (January 10, 2004). "A yen for romance". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 2009-03-16.

- ^ Travers, Peter (September 8, 2003). "Lost in Translation". Rolling Stone. Retrieved 2011-03-10.

- ^ Hoberman, J (September 9, 2003). "After Sunset". Village Voice. Retrieved 2009-03-16.

- ^ Mitchell, Wendy (January 9, 2004). "LA Critics Choose Splendor, Friedmans Follow-Up, Texas Picks, and More". indieWIRE. Retrieved 2009-03-13.

- ^ Hernandez, Eugene (January 5, 2004). "National Film Critics Group Names American Splendor Top Film of '03". indieWIRE. Retrieved 2009-03-13.

- ^ Hernandez, Eugene (December 16, 2003). "NY Critics Crown King Top Film of '03; SF & Boston Critics Also Weigh In". indieWIRE. Retrieved 2009-03-13.

- ^ Mitchell, Wendy (December 4, 2003). "National Board of Review Says Mystic River is Tops For 2003". indieWIRE. Retrieved 2009-03-13.

- ^ "Metacritic: 2003 Film Critic Top Ten Lists". Metacritic. Archived from the original on 2007-12-25. Retrieved 2009-03-25.

- ^ "Lost in Translation (2003)". Chicago Sun-Times.

- ^ "The 50 Best Movies of the Decade (2000-2009)". Paste Magazine. November 3, 2009. Retrieved December 14, 2011.

- ^ Geier, Thom; Jensen, Jeff; Jordan, Tina; Lyons, Margaret; Markovitz, Adam; Nashawaty, Chris; Pastorek, Whitney; Rice, Lynette; Rottenberg, Josh; Schwartz, Missy; Slezak, Michael; Snierson, Dan; Stack, Tim; Stroup, Kate; Tucker, Ken; Vary, Adam B.; Vozick-Levinson, Simon; Ward, Kate (December 11, 2009), "THE 100 Greatest MOVIES, TV SHOWS, ALBUMS, BOOKS, CHARACTERS, SCENES, EPISODES, SONGS, DRESSES, MUSIC VIDEOS, AND TRENDS THAT ENTERTAINED US OVER THE PAST 10 YEARS". Entertainment Weekly. (1079/1080):74-84

- ^ http://www.csmonitor.com/2004/0419/p07s01-woap.html

- ^ a b Day, Kiku (24 January 2004). "Totally lost in translation". London: The Guardian. Retrieved 2010-10-10.

- ^ http://www.asianamericanfilm.com/archives/000602.html

- ^ Stubbs, David (4 December 2004). "No more heroes: film". London: The Guardian. Retrieved 2012-06-19.

- ^ Burgess, Steve (26 April 2004). "Found in Translation". Maclean's. 117 (17). Rogers Communications: 38–39. ISSN 0024-9262.

- ^ Antepara, Robin (8 April 2005). "Culture Matters: Americans through Japanese Eyes". Commonweal. 132 (7). Commonweal Foundation: 10–11. ISSN 0010-3330.

- ^ Rich, Motoko; Lukas Schwarzacher; Fumie Tomita (Jan 4, 2004). "Land Of the Rising Cliché". The New York Times. Retrieved Mar 15, 2014.

- ^ "Academy Awards Best Screenplays and Writers". Filmsite.org. Retrieved 2011-02-19.

- ^ "Box Office Prophets Film Awards Database: Best Adapted Screenplay 2003". Boxofficeprophets.com. Retrieved 2011-02-19.

- ^ Hernandez, Eugene (January 26, 2004). "Lord of the Rings and Lost in Translation Big Winners at Golden Globes". indieWIRE. Retrieved 2009-03-13.

- ^ Hernandez, Eugene (February 28, 2004). "Lost In Translation Tops Independent Spirit Awards, Station Agent Another Big Winner". indieWIRE. Retrieved 2009-03-13.

- ^ Hernandez, Eugene (February 23, 2004). "WGA Opts for Translation and Splendor, While SAG Goes for Rings". indieWIRE. Retrieved 2009-03-13.

- ^ Andy Patrizio (2004-02-03). "Lost in Translation - DVD Review at IGN". Dvd.ign.com. Retrieved 2011-02-19.

- ^ Fonseca, Nicholas (February 13, 2004). "Lost in Translation". Entertainment Weekly. Retrieved 2009-03-16.

- ^ 'Lost in Translation' Blu-ray Detailed and Delayed, a September 30, 2010 article from High-Def Digest

External links

- 2003 films

- 2000s comedy-drama films

- American independent films

- American comedy-drama films

- American romantic comedy films

- American films

- Films about language and translation

- Films set in hotels

- Films set in Tokyo

- Films set in Kyoto

- Films set in Japan

- Films shot in Tokyo

- Films shot in Japan

- Films directed by Sofia Coppola

- Films whose writer won the Best Original Screenplay Academy Award

- Films featuring a Best Musical or Comedy Actor Golden Globe winning performance

- Midlife crisis films

- Best Musical or Comedy Picture Golden Globe winners

- American Zoetrope films

- Focus Features films

- Universal Pictures films

- Constantin Film films

- Pathé films

- English-language films

- Best Foreign Film César Award winners

- Screenplays by Sofia Coppola

- Independent Spirit Award for Best Film winners