New wave of British heavy metal

| New Wave of British Heavy Metal | |

|---|---|

| Stylistic origins | |

| Cultural origins | 1978–1982, United Kingdom |

| Typical instruments |

|

| Derivative forms | |

| Fusion genres | |

| Extreme metal | |

| Regional scenes | |

| United Kingdom | |

| Other topics | |

| NWOAHM | |

The New Wave of British Heavy Metal (commonly abbreviated in NWOBHM) was a nationwide musical movement that started in the late 1970s in the United Kingdom and achieved international attention by the early 1980s. The term was first used by journalist Geoff Barton in the May 1979 issue of the British music newspaper Sounds, as a way of describing the emergence of new heavy metal bands in the late 1970s, during the period of punk rock's decline and the dominance of new wave music.

The New Wave of British Heavy Metal began as an underground phenomenon parallel to punk and largely ignored by the media, which, only through the promotion of rock DJ Neal Kay and Sounds' campaigning, reached the public consciousness and gained radio coverage, recognition and success in the UK. The movement involved mostly young, white, male and working class musicians and fans, who suffered the hardships of the diffuse unemployment condition that hit Great Britain for years after the 1973–75 recession. As a reaction, they created a community separated from mainstream society where to enjoy each other's company and their favourite loud music. It evolved in a new subculture with its own behavioural and visual codes and a shared set of values, which were quickly accepted by metal fans worldwide following the almost immediate diffusion of the music in the US, Europe and Japan.

Although fragmented in a collection of different styles, the music of the New Wave of British Heavy Metal is best remembered for drawing from the heavy metal of the 70s and fusing it with the intensity of punk rock, producing fast and aggressive songs. The DIY attitude of the new metal bands caused the diffusion of raw-sounding self-produced recordings and the proliferation of independent record labels. The song lyrics were usually about typically escapist themes, like mythology, fantasy, horror and rock lifestyle.

The movement spawned about a thousand metal bands, but only a few survived the advent of MTV and the rise of the more commercial glam metal in the second half of the 80s. Among them, only Iron Maiden and Def Leppard became international stars, although Motörhead and Saxon also had considerable success. Other groups, like Diamond Head, Venom and Raven, remained underground acts, but were a major influence for the very successful extreme metal subgenres of the late-80s and 90s. Many bands from the New Wave of British Heavy Metal reformed in the 2000s and are still active with live performances and new studio albums.

Background

Social unrest

The United Kingdom in the second part of the 70s was in a state of social unrest and diffused poverty.[1] The percentage of unemployed, especially among young people of the working class, was exceptionally high after a three-year-long period of economic recession,[2] when the politics of both Conservative and Labour Party governments had failed to find solutions for the social distress of large parts of the population.[3][4] As consequence of the progressive deindustrialisation of the country, the rate of unemployment continued to rise in the early 80s and reached the record of 3,224,715 people in February 1983.[5] The discontent of so many people caused widespread social unrest, frequent strikes and culminated with a series of riots in 1981 (see 1981 Brixton riot, 1981 Toxteth riots).[6] The explosion of new bands and new musical styles coming from Great Britain in the late 70s is considered by most observers a consequence of the economic depression that hit the country before the governments of Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher, when the crowd of young people, deprived of the prospect of a job as factory workers or clerks that had befallen the previous generations, searched for different ways of earning money in the musical and entertainment business.[7]

New groups seem to be popping up every five minutes formed by guys who aren't dedicated to the music, but who think it's an easy way to make a fast buck...

The desperation and the violent reaction of a generation robbed of a safe future are well represented by the British punk movement of 1977–78, whose rebellion against the establishment continued diluted in new wave and post-punk music of the 80s.[9] These punks were politically militant, relished their anarchic attitude and stage practices like pogo, sported short and spiked hairstyles or shaved heads, wore safety pins and ripped clothes[10][11] and considered musical prowess unimportant as long as their music was simple and loud.[2] However, not all the working class male youths were taken by the punk movement, because some preferred to escape from their grim reality in heavy metal, which provided fun, stress relief and the companionship of their peers, all things stripped away from them because of their unemployment.[12]

Heavy rock in the UK

The United Kingdom had been one of the cradles of the first heavy metal movement, born at the end of the 60s and flowered in the early 70s.[13] Of the many British bands that came to prominence in that period, Led Zeppelin, Black Sabbath and Deep Purple reached worldwide success and critical acclaim.[14][15] The success of the music genre, usually called heavy rock at the time,[16] generated a community of fans in Great Britain with strong ties to psychedelia, hippie doctrines and biker subculture.[17] All three bands cited above were in crisis in the mid-to-late 70s: Led Zeppelin were plagued by discord and personal tragedies and reduced drastically their activities,[14][18] Black Sabbath finally fired their charismatic but unreliable frontman Ozzy Osbourne[15] and Deep Purple disbanded.[19] As consequence, the whole movement lost much of its momentum and the interest of the media, focused on "the more fashionable or lucrative markets of the day such as disco, glam, mod, new wave and electronic music."[20] Just like progressive rock acts and other mainstream music groups of the 70s, heavy rock bands were viewed as "lumbering dinosaurs" by the music press infatuated with punk rock and new wave,[21][22] despite the fact that the major labels rushing to put punk bands under contract were the same that had supported the objects of their rage in the recent past.[18][23] Some writers even declared the premature demise of heavy metal altogether.[24]

The crisis of British heavy rock giants left space in the mid-70s to the rise of other bands,[25] like Queen,[26] Slade,[27] Sweet,[28] Wishbone Ash,[29] Status Quo,[30] Nazareth,[31] and Uriah Heep,[32] all of which had multiple chart entries in the UK and successful international tours.[20] The British chart results of the period show that there was still a vast audience for heavy metal in the country and also upcoming bands Thin Lizzy,[33] UFO[34] and Judas Priest,[35] had tangible success and media coverage in the late 70s.[36] Foreign hard rock acts, such as Blue Öyster Cult and Ted Nugent from the US,[37][38] Rush from Canada,[39] Scorpions from Germany[40] and especially AC/DC from Australia,[41] climbed the British charts in the same period.[20]

Motörhead

Motörhead were a band founded in 1975 by already experienced musicians (their leader Ian 'Lemmy' Kilmister came from the space rock band Hawkwind,[43] Larry Wallis from Pink Fairies,[44] Eddie Clarke from Curtis Knight's Zeus[45]), which divides the critics about its belonging to the New Wave of British Heavy Metal. Some of them think that the band should be considered a precursor and inspirer of the movement but not part of it, because they gained recording contracts, toured the country and reached chart success before any NWOBHM band stepped out of their local club scene.[46][47] Motörhead were also the only metal band of the period recording songs with veteran BBC radio DJ John Peel for his "Peel Sessions" program[48] and the first to reach No. 1 in the UK Albums Chart, with the live album No Sleep 'til Hammersmith in June 1981.[47] Lemmy himself said that "the NWOBHM ... didn't do us much good", because Motörhead "came along a bit too early for it."[49]

Other critics see Motörhead as chronologically the first significant exponent of the movement[50][51] and the first band to fully implement a crossover between punk rock and heavy metal.[52] Their fast music, the renunciation to technical virtuosity in favour of sheer loudness and their uncompromising attitude were equally welcomed by punks and heavy metal fans.[52] Motörhead were supported by many NWOBHM bands on tour,[18][53] but they also shared the stage with the punk band The Damned, of which Lemmy was a friend.[54] Motörhead's musical style became very popular during the New Wave of British Heavy Metal, making them a fundamental reference for the nascent movement and for musicians of various metal subgenres in the following decades.[55]

Identity and style

The New Wave of British Heavy Metal was a musical movement that involved both musicians and fans, linked by young age, prevalent male sex and white skin, class origin, ethic and aesthetic values.[56] According to American sociologist Deena Weinstein, the rise and growth of the movement meant the achievement of maturity for heavy metal, before branching out into various subgenres.[57] British heavy metal fans, commonly known as muthas, metalheads or headbangers for the typical movement of their head while listening to metal music,[58] dismissed the simplistic image of rebellious youth inherited from the counterculture of the 1960s[59] and the psychedelic attachments characteristic of heavy rock in the 70s,[60] creating a subculture separated from mainstream society,[61] with shared principles and codes for both artists and themselves.[62]

In the last part of the 70s, British metalheads coalesced in a closed community of peers that exalted power and celebrated masculinity.[63] Weinstein wrote that "British heavy metal is neither misogynistic nor an expression of machismo; for the most part women are of no concern."[64] At the same time, it "is not racist, despite its uniformly white performers, and its lyrics are devoid of racial references",[64] though the movement appears strongly homophobic.[65] Headbangers showed scarce interest in political and social problems, finding in each other's company, in the consumption of beer and in the music the means to escape their bleak reality,[66] and for this reason they were often accused of nihilism[67] or escapism.[68] In contrast with punks, they loved musicianship and made idols of guitar virtuosos and singers,[69] with the live show viewed as the epiphany of their status.[70] Michael Schenker and Eddie Van Halen were the most celebrated young guitar heroes of the time.[71][72] The fans were very loyal to the music, to each other and to the bands, with which they shared the same origins and from which required coherence with their values, authenticity and continuous accessibility.[73] To depart from this strict code meant being marked as 'sell out' or 'poseur' and being somewhat excluded from the community.[74] The lyrics of the song "Denim and Leather" by Saxon reflect precisely the condition of British metalheads in those years of great enthusiasm.[75] Access to this male-dominated world for female musicians and fans was not easy, and only women who adapted to their male counterparts' standards and codes were accepted,[76] as attested by Girlschool[18][77] and Rock Goddess,[78] the only notable all-girl metal bands of that age.

The music, philosophy and lifestyle of heavy metal bands and fans were often panned by both left-wing critics and conservative public opinion,[79] described as senseless, ridiculous to the limit of self-parody[80] and even dangerous for the young generations.[81] The 1984 successful mockumentary This Is Spinal Tap addressed many idiosyncrasies of British metal bands, showing comic sides of that world which external observers would judge absurd.[18][82] Instead metal musicians regarded the movie's content as much too real.[18][83]

Visual aspects

The dress code of the British headbangers reflected the newly-found cohesion of the movement and recalls the look of 60s' rockers and American bikers.[84] The common threads were to sport long hair and wear jeans, black or white T-shirts with band logos and cover art, leather jackets or denim vests adorned with patches.[58] Following the example of Judas Priest, elements of S&M fashion were introduced in the metal wardrobe of the 80s and it became typical to show off metallic studs and ornaments or to see spandex and leather trousers worn by heavy metal musicians.[85] Elements of militaria, like bullet belts and insignia, were also introduced at this time.[86] This style of dress quickly became the uniform of metalheads worldwide.[87]

Most bands of the New Wave of British Heavy Metal had the same look of their fans and produced typical rock shows, loud and noisy but without special effects. A relevant exception was Iron Maiden, which created the character Eddie the Head to enrich their performances very early in their career.[88] Other exceptions were Demon,[89] Cloven Hoof[90] and Samson,[91] which used various props, costumes and tricks in their shows, while Pagan Altar[92] and Venom became well known for their elaborated scenography inspired by shock rock and satanism.[93]

Music and lyrics

People say Rush is heavy metal and so is Motörhead. They are worlds apart, yet they come under the same heading.

The marketing of record labels and the general media of the 80s dubbed all rock music with loud guitars of that period with the umbrella term heavy metal, reducing the New Wave of British Heavy Metal to a single music genre,[95][96][97] when the movement actually comprised bands with very different influences and styles.[98][99] Especially in the first years of the movement, what characterised the flood of heavy metal music was its raw sound, due in large part to low-budget productions, but also to the amateurish talents of many young bands.[100] Those young musicians were largely inspired by the works of the aforementioned successful bands of the 70s and by other minor groups like Budgie,[101] representing a sort of continuity with those heavy rock acts, whose music had gone temporarily out of fashion but was still vital underground.[102]

In a semi-conscious way, many new bands fused classic heavy metal with the immediacy of pub rock and the intensity of punk rock, implementing to various degrees the crossover of genres started by Motörhead;[103] in general they shunned ballads, reduced harmonies and produced shorter songs with sped up tempos and a very aggressive sound based on riffs and power chords, which featured vocals ranging from high pitch wails to gruff and low tuned.[104] Iron Maiden,[105] Angel Witch,[106] Saxon,[107] Holocaust,[108] Tygers of Pan Tang,[109] Girlschool,[110] Tank[111][112] and More[113] are notable performers of this style, which bands like Atomkraft,[114] Jaguar,[115] Raven[116] and Venom[117] stretched to even more extreme solutions. This new approach to heavy metal is considered by critics the greatest musical accomplishment of the New Wave of British Heavy Metal and a giant evolutionary step for the genre.[10][118]

However, a style more melodic and more akin to the hard rock of bands like Rainbow, Magnum, UFO, Thin Lizzy and Whitesnake was equally represented during the New Wave of British Heavy Metal.[120] The music of Def Leppard,[121] Praying Mantis,[122] White Spirit,[123] Demon,[89] Shy,[124] Gaskin,[125] Dedringer[126] and many others contained hooks as much as riffs, often retained a closer link with blues rock,[127] included power ballads and featured keyboards, acoustic instruments, melodic and soaring vocals. In particular after the peak of the movement in 1981, this style more similar to that of mainstream American acts was favoured by the media and found a larger consensus in the British audience, becoming prevalent when also bands of the first group adopted it.[128] These changes of musical direction disoriented the less compromising fans and brought to the rejection of the bands which, to their eyes, had lost their coherence to pursue an elusive success.[129]

The two said styles do not exhaust all the musical influences found in the British metal music of the early 80s, because many bands were also inspired by progressive rock (Iron Maiden,[105] Diamond Head,[130] Blitzkrieg,[131] Demon,[89] Saracen,[132] Shiva,[133] Witchfynde[134]), boogie rock (Saxon,[135] Vardis,[136] Spider,[137][138] Le Griffe[139]) and glam rock (Girl,[140] Wrathchild[141]). Doom metal bands Pagan Altar and Witchfinder General were also part of the New Wave of British Heavy Metal and their albums are considered among the best examples of that already established subgenre.[92][138]

British writer John Tucker wrote that NWOBHM bands "were in general fuelled by 'first pints, first shags and first horror films' and their lyrics rolled everything into one big youthful fantasy".[142] In fact, they usually avoided social and political themes in their lyrics[143] or treated them in a shallow "street level" way,[144] using instead more frequently topics taken from mythology, the occult, fantasy, science fiction and horror films.[145] Songs about romance and lust were rare,[146] but the frequent lyrics about male bonding and rock lifestyle contain many sexist allusions.[147] Christian symbolism is often present in the lyrics and cover art,[148] as is the figure of Satan, used more as a shocking and macabre subject than as the antireligious device of 90s' black metal subculture.[149]

History

An underground movement (1975–78)

Thin Lizzy, UFO and Judas Priest were already playing international arenas,[151][152][153] when new heavy metal bands, composed by very young people, debuted in small venues in many cities of Great Britain.[10] The larger venues of the country were usually reserved for the chart-topping disco music, as "the concept of a rock club was pretty much unconceivable around 1978–79".[154] Just like most British bands in the past, the new groups spent their formative years playing live in clubs, pubs, dance halls and social circles for low wages; this training honed their skills, created a local fan base and enabled them to come in contact with managers and agents of record labels.[155]

Angel Witch, Iron Maiden, Praying Mantis and Samson from London,[156][157][158][159] Son of a Bitch (later Saxon) from Barnsley,[135] Diamond Head from Stourbridge,[160] Marseille from Liverpool,[161] White Spirit from Hartlepool,[162] Witchfynde from Derbyshire,[163] Vardis from Wakefield,[164] Def Leppard from Sheffield,[165] Raven and Tygers of Pan Tang from around Newcastle,[166][167] and Holocaust from Edinburgh[168] were the most important metal bands founded between 1975 and 1977 that animated the club scene of their respective cities and towns.[169] The first bands of the new-born musical movement contended space in the venues to punk outfits, causing often the specialisation of clubs, which proposed only punk or only rock and hard rock.[170] Differences in ideology, attitude and looks caused also heated rivalries between the two audiences.[10][170] What punk and heavy metal musicians had in common was their DIY attitude towards the music business and the consequent practice of self-production and self-distribution of recorded material, in the form of audio cassette demos and privately pressed singles, initially addressed only to local supporters.[6] It caused also the birth and diffusion of small independent record labels, often an extension of record shops and independent recording studios, which sometimes produced both punk and metal releases.[171] Indie labels are considered very important for the movement's evolution, because they removed the intrusion of corporate business which had hindered rock music in the late-70s, giving local bands the chance to experiment with more extreme forms of music.[172]

NWOBHM was a fiction, really, an invention of Geoff Barton and Sounds. It was a cunning ruse to boost circulation. Having said that, it did represent a lot of bands that were utterly ignored by the mainstream media. Because of that it became real and people got behind it.

While punk was intensely covered by the British and international media, the new grassroots metal movement remained underground until 1978, largely ignored by popular music magazines such as New Musical Express, The Face and Melody Maker and by radio stations.[5] The transmission of the news concerning bands and music happened by word-of-mouth and fanzines,[173] or through interested DJs, who travelled the country from club to club. Neal Kay was one of those DJs, who started to work in 1975 at a disco club called the Bandwagon in Kingsbury, North West London, housed in the back-room of the Prince of Wales pub and equipped with a massive sound system.[174][175] He transformed his nights at the Bandwagon in The Heavy Metal Soundhouse, a spot specialised in hard rock and heavy metal music and a place to listen to albums of established acts and to demos of new bands,[174][176] which circulated among fans through cassette trading.[177] Besides participating in air guitar competitions[178] and watching live shows,[174] the audience could also vote for the selections made by Kay.[179] The DJ made a weekly Heavy Metal Top 100 list of the most requested songs at The Soundhouse by both newcomers and established bands, and sent it to record shops and to the music journal Sounds, the only paper showing interest in the developing heavy metal scene.[179] Many young musicians realised that they were not alone in playing metal only through that weekly list, which included bands from all over the country.[180] At the time, Geoff Barton was a staffer at Sounds who wrote features on the new up-and-coming metal bands and was pivotal in directing the developing subculture of metalheads with his keen articles.[18][181] Under suggestion from his editor Alan Lewis and in an attempt to find a common stylistic element out of the bands' music, he used for the first time the term 'New Wave of British Heavy Metal' in his review of a gig of the Metal Crusade tour, featuring Angel Witch, Iron Maiden and Samson, at The Music Machine in London, on 8 May 1979.[10][182] That newly coined term became soon the identifier of the whole movement.[183]

The first wave (1979–81)

Compilation albums featuring bands from the nascent movement started to circulate, issued by Neat Records, Heavy Metal Records and Ebony Records, which would become leaders in the market of independent metal labels during the 80s.[185] The fresh outlet of the Neal Kay's chart, the attention of Sounds and the many compilations issued by indie labels focused the efforts of the new bands in producing demos and singles.[186] Iron Maiden's The Soundhouse Tapes is one of the best known collection of such demos.[187] As Barton recalls: "There were hundreds of these bands. Maybe even thousands. Barely a day would go by without a clutch of new NWOBHM singles arriving in the Sounds office."[18]

Tommy Vance, a BBC radio host, took notice of the phenomenon and played singles of the new metal bands at his late night Friday Rock Show on BBC Radio 1.[18] Along with John Peel's broadcast,[18][188] Vance's was the only corporate radio show to feature songs from underground metal acts, many of which were invited to play live at BBC studios under supervision of long-time collaborator and producer Tony Wilson.[189] Alice's Restaurant Rock Radio, a pirate FM radio station of the capital,[190] also championed the new bands on air and with their own 'roadshow' in rock pubs and clubs.[191]

Despite the transition of the young bands from being local attractions to touring extensively the UK, A&R agents of the major record labels were still unable to ascertain the rising new trend.[192] Thus, most new bands signed contracts with small indie labels, which could only afford limited printings of singles and albums and usually offered only national distribution.[193] Many other bands, including Iron Maiden, Def Leppard and Diamond Head, self-produced their first releases and sold them through mail order or at concerts.[194] Saxon were the first to sign with an internationally distributed label, the French Carrere Records,[195] followed by Def Leppard with Phonogram in August 1979[196] and Iron Maiden with EMI in December 1979.[197] In early-1980, EMI tested the market with the Neal Kay-compiled album Metal for Muthas and with a UK tour of the bands that had contributed to the compilation,[198] eventually signing Angel Witch and Ethel the Frog[199] (Angel Witch were dropped after the release of their first single[200]).

Metal for Muthas was put down by Sounds, but was a commercial success[201] and may have been instrumental in urging major labels to sign more bands; A II Z went to Polydor,[202] Tygers of Pan Tang, Fist and White Spirit to MCA,[203] More to Atlantic,[113] Samson to RCA,[204] Demon to Carrere,[205] Girlschool to Bronze[206] and Praying Mantis to Arista.[207] The new releases by those bands were produced better and, together with intensive tours in the UK and Europe,[208] promoted definitely the movement to relevant national phenomenon, as evidenced by the good chart results of many of those first albums.[209][210][211] The best chart performances of that period were for Iron Maiden's debut album and for Wheels of Steel by Saxon, which reached No. 4 and No. 5 in the UK Albums Chart respectively, while their singles "Running Free", "Wheels of Steel" and "747 (Strangers in the Night)" entered the UK Singles Chart Top 50.[212][213] The immediate consequence of that success was increased media coverage for metal bands, which included appearances on the British music TV shows Top of the Pops[214][215][216] and The Old Grey Whistle Test.[217] Another remarkable effect of the expansion of the movement was the emergence of many new bands in the period between 1978 and 1980, the most notable of which were Savage,[218] Girlschool,[219] Trespass,[220] Demon,[221] Mama's Boys,[222] Fist,[223] Witchfinder General,[224] Satan,[225] Grim Reaper,[226] Venom,[227] Persian Risk,[228] Sweet Savage,[229] Blitzkrieg,[230] Jaguar[231] and Tank.[232]

The New Wave of British Heavy Metal was also beneficial to already established bands, which reclaimed the spotlight with new and acclaimed releases.[233] Ex-Deep Purple singer Ian Gillan returned to sing heavy metal with the album Mr. Universe in 1979[234] and was on the forefront of the British metal scene with his band Gillan in the following years.[235] His former band mate in Deep Purple Ritchie Blackmore also climbed the UK charts with his hard rock group Rainbow's releases Down to Earth (1979) and Difficult to Cure (1981).[236][237] Black Sabbath got back in shape and returned to success with the albums Heaven and Hell (1980) and Mob Rules (1981),[238][239] featuring the ex-Rainbow singer Ronnie James Dio.[240] 1980 stands out as a memorable year for hard rock and heavy metal in the British charts, with many other entries in the top 10: MSG's first album peaked at No. 8,[241] Whitesnake's Ready an' Willing at No. 6,[242] Judas Priest's best-seller British Steel[35] and Motörhead' s Ace of Spades at No. 4,[47] while Back in Black by AC/DC reached number one.[41]

As proof of the successful revival of the British hard rock and metal scene, tours and gigs of old and new acts went sold out, both in the UK and in other European countries, where the movement had spread out.[243] World tours were no longer precluded to the groups generated from the NWOBHM, which were chosen as opening acts for major bands in arenas and stadiums: Iron Maiden supported Kiss in Europe in 1980[244] and embarked in their first world tour as headliners in 1981,[245] besides opening for Judas Priest and UFO in the US;[246] Def Leppard visited the US for the first time in 1980 for a three-month trek supporting Pat Travers, Judas Priest, Ted Nugent, AC/DC and Sammy Hagar;[247] Saxon opened for Judas Priest in Europe and for Rush and AC/DC in the US in 1981.[248][249] NWOBHM bands were present in the roster of the famous Reading Festival already in 1980[250][251] and were quickly promoted to headliners in the editions of 1981[252] and 1982.[253] The 1980 edition was remarkable also for the violent protest against Def Leppard, whose declared interest for the American market was badly received by British fans.[254] In addition to Reading, a new festival called Monsters of Rock was created in 1980 at Castle Donington, England, to showcase only hard rock and heavy metal acts.[58][255]

Into the mainstream (1982–83)

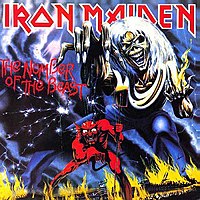

The New Wave of British Heavy Metal eventually found space on newspapers and music magazines different from Sounds, as journalists caught up with the "next big thing" happening in the UK.[257] Melody Maker even published a weekly heavy metal chart based on the sales of record shops.[258] Sounds publisher cashed in for his support to the movement issuing in June 1981 the first number of Kerrang!, a colour magazine directed by Geoff Barton, exclusively devoted to hard rock and heavy metal.[259] Kerrang! was a huge success and soon became the magazine of reference for metalheads worldwide,[260] followed shortly by the American Circus and Hit Parader, the German Metal Hammer and the British Metal Forces.[261] The attention of international media meant more sales of records and more world tours for NWOBHM bands, whose albums entered in many foreign charts.[262][263][264][265][266] Their assault to the British charts culminated with Iron Maiden's The Number of the Beast topping the UK Albums Chart on 10 April 1982 and staying at number 1 for two weeks.[267][268]

The success of the music produced by the movement and its passage from underground phenomenon to mainstream genre induced its main promoter Geoff Barton to declare finished the New Wave of British Heavy Metal in 1981,[269] in coincidence with the closure of the Bandwagon and subsequent demolition of the Prince of Wales pub to build a restaurant.[270] Although the movement had lost some of its appeal for the diehard fans, as evidenced by the increased popularity of "American influenced AOR releases" on national polls,[271] it retained enough vitality to launch a second wave of bands, which rose up from the underground and released their first albums in the period 1982–1983.[272] Avenger,[273] Rock Goddess,[78] Tysondog,[274] Tokyo Blade,[275] Elixir,[276] Atomkraft[277] and Rogue Male[278] are some of the bands that came to the spotlight after 1981.

NWOBHM bands had been steadily touring in the United States, but had not yet received enough FM radio airplay in that country to make a significant impression on American charts.[279] Def Leppard remedied to that, releasing at the beginning of 1983 Pyromania, an album which renounced to much of the aggressive sound of their older music for a more melodic and FM-friendly approach.[280] The band's goal of reaching a wider international audience, which included many female fans, was attained completely in the US,[281] where Pyromania peaked at No. 2 on the Billboard 200 chart behind Michael Jackson's Thriller.[282] Thanks to a string of hit singles and the smart use of music videos on the recently born MTV, the album had sold more than six millions copies in the US by 1984 and made Def Leppard superstars.[283] The overwhelming international success of Pyromania induced both American and British bands to follow Def Leppard's example,[284][285] giving a decisive boost to the more commercial and melodic glam metal and delivering a fatal blow to the New Wave of British Heavy Metal.[286]

Decline

Great Britain had been a pioneer of music videos, which suddenly stepped up from occasional promotional fancy to indispensable means to reach the audience when MTV started its broadcasting service in 1982.[287] The new TV broadcaster filled its programs with many hard rock and heavy metal videos,[288] too expensive for bands without a recording contract or signed to small independent labels.[289] Moreover, music videos exalted the visual side of a band, a department where British metal groups were often deficient.[290][291][292] So the New Wave of British Heavy Metal suffered the same decline as other musical movements based on low-budget productions and an underground following.[293] Many of its leaders, like Diamond Head, Tygers of Pan Tang, Angel Witch and Samson, were unable to follow up on their initial success and their attempts to update their sound and look to the new standards expected by the wider audience failed, alienating also the favours of fans of the first hour.[294] By the mid-1980s, image-driven and sex-celebrating glam metal emanating from Hollywood Sunset Strip, spearheaded by Van Halen and followed by bands such as Mötley Crüe, Quiet Riot, Dokken, Great White, Ratt and W.A.S.P., quickly replaced other styles of metal in the tastes of many British rock fans.[286] New Jersey act Bon Jovi and the Swedish Europe, thanks to their successful fusion of hard rock and romantic pop,[295] became also very popular in the UK, with the first arriving even to headline the Monsters of Rock Festival in 1987.[296] Record companies latched onto the more sophisticated glam metal subgenre over the NWOBHM bands, which maintained a fan base in Europe, but found the home and US markets closed by American groups.[286]

In addition, new but much less mainstream metal subgenres emerged around the same time and attracted many British metalheads. Power metal and thrash metal, both stemming from the New Wave of British Heavy Metal and maintaining much of its ethos,[298] were even faster and heavier and obtained good sale results and critical acclaim in the second half of the 80s,[99][299] with bands like Helloween,[300] Savatage,[301] Metallica,[302] Slayer,[303] Megadeth[304] and Anthrax.[305]

The New Wave of British Heavy Metal Encyclopedia by Malc Macmillan lists more than 500 recording bands established in the decade between 1975 and 1985 and related to the movement,[258] the last notable ones being Baby Tuckoo,[306] Chrome Molly,[307] Tredegar[308] and Battlezone.[309] Probably as many bands were born in the same time interval, but never emerged from their local club scene or recorded nothing more than demos or limited pressings of self-produced singles.[96][310] The disinterest of record labels, bad management, internal struggles and wrong musical choices that turned off much of their original fan base won the tenacity of almost all of those bands, which disbanded and disappeared by the end of the decade.[311] A few of the best known groups survived on foreign markets, like Praying Mantis in Japan[122] and Saxon, Demon and Tokyo Blade in Europe.[312][313] Some others, namely Raven,[314] Girlschool[315] and Grim Reaper,[316] tried to break through in the US market signing with American labels, but their attempts got no lasting results.

Two of the more popular bands of the movement, however, went on to considerable, lasting success. Iron Maiden has since then become one of the most commercially successful and influential heavy metal bands of all time,[317] even after adopting a more progressive style.[105] Def Leppard became even more successful, targeting the American mainstream rock market with their more refined hard rock sound.[318]

Revival

The widespread popularity of the Internet in the late 1990s/early 2000s helped NWOBHM fans and musicians to communicate again.[310] So the New Wave of British Heavy Metal experienced a minor revival, highlighted by the good sales of old vinyl and collectibles and by the demand of new performances.[319] The statements of appreciation by metal bands of the 90s,[320][321] the success of tribute bands, the re-issues of old albums and the production of new thoroughly edited compilations renewed the attention of the media and encouraged many of the original groups to reform for festival appearances and tours.[322] Probably the most important of those compilation albums, entitled New Wave of British Heavy Metal '79 Revisited, was compiled by Metallica's drummer Lars Ulrich and former Sounds and Kerrang! journalist Geoff Barton and released in 1990 as a double CD, featuring bands as obscure as Hollow Ground right through to the major acts of the era.[96]

A new publication called Classic Rock, featuring Barton and many of the writers from Kerrang!'s first run, championed the NWOBHM revival and continues to focus much of its attention on rock acts from the 80s.[323] Starting in the 2000s, many reformed bands recorded new albums and revisited their original styles, abandoned in the second half of the 80s.[324][325] Their presence at metal festivals and in the international rock club circuit has been constant ever since.[18]

Influences and legacy

The New Wave of British Heavy Metal re-ignited the creativity of a stagnant genre, but was heavily criticised for the excessive hype generated by local media in favour of mostly talentless musicians who, unlike the preceding decades, were unoriginal[327] and created no classic rock recording.[97][328] Nonetheless, the music produced during the New Wave of British Heavy Metal was very influential for their contemporaries in every part of the Western world;[99][329] today that hodgepodge of styles is seen as a nodal point for the diversification of heavy metal and an incubator of various subgenres, which developed in the second half of the 80s and became predominant in the 90s.[96][330] In fact, the great success of Def Leppard in the US was very important for the growth of glam metal,[331] just as the music, lyrics, cover art and attitude of bands like Angel Witch, Witchfynde, Cloven Hoof and especially Venom are regarded as fundamental for the development of black metal in its various forms in Europe and America.[332] The name attributed to that subgenre comes from Venom's album Black Metal of 1982.[80] Motörhead, Iron Maiden, Raven, Tank, Venom and other minor groups are viewed as precursors of speed metal and thrash metal, two subgenres which carried forward the crossover with punk, incorporating elements of hardcore and amplifying velocity of execution, aggression and loudness.[333][334] Starting around 1982, North America,[335] West Germany,[336] and Brazil[337] became the principal hotbeds for thrash metal outfits, giving birth to clearly defined regional scenes (see Bay Area thrash metal, Teutonic thrash metal, Brazilian thrash metal). Lars Ulrich, in particular, was an active fan and avid collector of NWOBHM recordings and memorabilia and, under his influence, the set lists of Metallica's early shows were filled with covers of British metal groups.[338]

The birth of speed metal in the early 80s was also decisive for the evolution of power metal in the second half of the decade,[340] with most notable exponents the German Helloween[299] and the American Manowar,[341] Savatage[301] and Virgin Steele.[342]

Since the beginning of the NWOBHM, North American bands like Anvil,[343] Riot,[343] Twisted Sister,[344] Manowar,[343] Virgin Steele,[345] The Rods,[346][347] Hellion,[348] Cirith Ungol[349] and Exciter[350] had a continuous exchange with the other side of the pond, where their music was appreciated by British metalheads.[351] In this climate of reciprocity, Manowar and Virgin Steele initially signed with the British indie label Music for Nations, while Twisted Sister recorded their first two albums in London.[344]

The sound of Japanese bands Earthshaker, Loudness, Anthem and other minor groups was also influenced by the New Wave of British Heavy Metal, whose British sound engineers they used for their early albums.[352] The Japanese band Bow Wow even transferred to England to be part of the British metal scene.[353]

Germany, Sweden, Denmark, Belgium, Netherlands, France and Spain were the first European countries which welcomed the new British bands and spawned imitators almost immediately.[351] Acts like Accept, Grave Digger, Sinner and Warlock from Germany,[354][355][356][357] E. F. Band from Sweden,[358] Mercyful Fate from Denmark,[359] Picture and Bodine from the Netherlands,[360][361] Trust and Nightmare from France,[362][363] Barón Rojo and Ángeles del Infierno from Spain,[364][365] were born between 1978 and 1982 and were heavily influenced by the sound of the New Wave of British Heavy Metal. Many of those bands signed with the Dutch Roadrunner Records or with the Belgian Mausoleum Records, indie labels which published also recordings of British NWOBHM acts.[366][367]

See also

Notes

- ^ Zarnowitz & Moore 1977.

- ^ a b Christe 2004, p. 30.

- ^ "1974 Feb: Hung parliament looms". BBC News. 5 April 2005.

- ^ "1974 Oct: Wilson makes it four". BBC News. 5 April 2005.

- ^ a b Tucker 2006, p. 22.

- ^ a b Macmillan 2012, p. 21.

- ^ Tucker 2006, p. 24-25.

- ^ Barton 1980a.

- ^ "British Punk". AllMusic. Retrieved 17 June 2015.

- ^ a b c d e Barton, Geoff (16 August 2005). "HM Soundhouse Special Features: The New Wave of British Heavy Metal". HMsoundhouse.com. Retrieved 18 March 2015.

- ^ Weston Thomas, Pauline. "1970s Punk Fashion History Development". Fashion Era.com. Retrieved 21 April 2015.

- ^ Bayer 2009, pp. 145–146; Macmillan 2012, p. 21

- ^ Weinstein 2000, p. 14-18.

- ^ a b Erlewine, Stephen Thomas. "Led Zeppelin Biography". AllMusic. Retrieved 26 April 2015.

- ^ a b Welch 1988.

- ^ Hatch & Millward 1987, p. 167-168.

- ^ Walser 1993, p. 3; Weinstein 2000, p. 18

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Mitchell, Ben (13 April 2014). "Inside the World of New Wave of British Heavy Metal". Esquire. Retrieved 3 May 2015.

- ^ Thompson 2004, p. 191.

- ^ a b c Macmillan 2012, p. 19.

- ^ Bushell & Halfin 1984, p. 24.

- ^ "When Dinosaurs Roamed The Earth..." Punk77.co.uk. Retrieved 2 May 2015.

- ^ Christe 2004, p. 28.

- ^ Johnson 1979, p. 42; Smith 1978, pp. 17–30

- ^ Thompson 2004, p. 201.

- ^ "Queen – Official Charts". Official Charts Company. Retrieved 21 April 2015.

- ^ "Slade – Official Charts". Official Charts Company. Retrieved 21 April 2015.

- ^ "Sweet – Official Charts". Official Charts Company. Retrieved 21 April 2015.

- ^ "Wishbone Ash – Official Charts". Official Charts Company. Retrieved 21 April 2015.

- ^ "Status Quo – Official Charts". Official Charts Company. Retrieved 21 April 2015.

- ^ "Nazareth – Official Charts". Official Charts Company. Retrieved 21 April 2015.

- ^ "Uriah Heep Official Cahrts". Official Charts Company. Retrieved 17 May 2015.

- ^ "Thin Lizzy – Official Charts". Official Charts Company. Retrieved 21 April 2015.

- ^ "UFO – Official Charts". Official Charts Company. Retrieved 21 April 2015.

- ^ a b "Judas Priest – Official Charts". Official Charts Company. Retrieved 21 April 2015.

- ^ Macmillan 2012, p. 19; Tucker 2006, p. 36

- ^ "Blue Oyster Cult – Official Charts". Official Charts Company. Retrieved 21 April 2015.

- ^ "Ted Nugent – Official Charts". Official Charts Company. Retrieved 21 April 2015.

- ^ "Rush – Official Charts". Official Charts Company. Retrieved 21 April 2015.

- ^ "Scorpions – Official Charts". Official Charts Company. Retrieved 21 April 2015.

- ^ a b "AC/DC – Official Charts". Official Charts Company. Retrieved 21 April 2015.

- ^ Prato, Greg. "Lemmy – Biography". AllMusic. Retrieved 28 August 2015.

- ^ Kilmister & Garza 2004, p. 69-95.

- ^ Kilmister & Garza 2004, p. 98.

- ^ Erlewine, Stephen Thomas. "Curtis Knight Biography". AllMusic. Retrieved 4 May 2015.

- ^ Anon. 2008, p. 94:00; Macmillan 2012, p. 19; Tucker 2006, p. 47

- ^ a b c "Motorhead Official Charts". Official Charts Company. Retrieved 17 May 2015.

- ^ "Keeping It Peel – Peel Sessions". BBC. Retrieved 28 April 2015.

- ^ Kilmister & Garza 2004, p. 150.

- ^ Christe 2004, p. 35; Dunn, McFadyen & Wise 2005, p. 12:00

- ^ "New Wave of British Heavy Metal". AllMusic. Retrieved 18 July 2015.

- ^ a b Waksman 2009, p. 170-171.

- ^ Millar 1980.

- ^ Kilmister & Garza 2004, p. 119-120.

- ^ Kilmister & Garza 2004, p. 181, 197, 211, 252.

- ^ Weinstein 2000, p. 101-102.

- ^ Bayer 2009, p. 21; Weinstein 2000, p. 8

- ^ a b c d Christe 2004, p. 37.

- ^ Weinstein 2000, p. 110.

- ^ Bayer 2009, p. 145-146.

- ^ Weinstein 2000, p. 139.

- ^ Weinstein 2000, p. 97-98.

- ^ Bayer 2009, pp. 24–25, 145–146; Moynihan & Søderlind 1998, p. X

- ^ a b Bayer 2009, p. 18.

- ^ Walser 1993, pp. 128–130; Weinstein 2000, p. 105

- ^ Weinstein 2000, p. 135.

- ^ Moynihan & Søderlind 1998, p. X; Walser 1993, p. 112

- ^ Bayer 2009, p. 37; Bushell & Halfin 1984, p. 24

- ^ Waksman 2009, p. 178, 219–220.

- ^ Weinstein 2000, p. 217-218.

- ^ Weinstein 2000, p. 59.

- ^ Prato, Greg. "Eddie Van Halen Biography". AllMusic. Retrieved 26 June 2015.

- ^ Bayer 2009, pp. 163–165; Dunn & McFadyen 2011, p. 30:18

- ^ Weinstein 2000, p. 137.

- ^ a b Bayer 2009, p. 19.

- ^ Weinstein 2000, p. 105.

- ^ Makowski 1980.

- ^ a b Macmillan 2012, p. 484-485.

- ^ Weinstein 2000, p. 237-239.

- ^ a b Moynihan & Søderlind 1998, p. 11-14.

- ^ Moynihan & Søderlind 1998, p. X; Weinstein 2000, pp. 237–239

- ^ "This Is Spinal Tap". Rotten Tomatoes. Retrieved 21 April 2015.

- ^ Yabroff, Jennie (11 April 2009). ""Spinal Tap" and Its Influence". Newsweek. Retrieved 9 January 2016.

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) (registration required) - ^ Weinstein 2000, p. 30.

- ^ Daniels 2010, pp. 72–74; Weinstein 2000, p. 30

- ^ Kilmister & Garza 2004, p. 224.

- ^ Bayer 2009, p. 27.

- ^ Bushell & Halfin 1984, pp. 13–16; Christe 2004, p. 35

- ^ a b c Rivadavia, Eduardo. "Demon biography". AllMusic. Retrieved 10 February 2012.

- ^ Miller 1986a.

- ^ Christe 2004, p. 39.

- ^ a b Rivadavia, Eduardo. "Pagan Altar Biography". AllMusic. Retrieved 22 March 2015.

- ^ Christe 2004, p. 42; Dunn 1982; Moynihan & Søderlind 1998, pp. 11–14

- ^ "Kelly Johnson – Making Music in a Man's World" (JPG). Guitar World. March 1984. p. 20. Retrieved 17 February 2015.

- ^ Tucker 2006, p. 33-34.

- ^ a b c d Rivadavia, Eduardo. "New Wave of British Heavy Metal '79 Revisited review". AllMusic. Retrieved 24 March 2015.

- ^ a b Shore, Robert (January 2009). "NWOBHM: 30 Years On". Planetrock.com. Retrieved 3 May 2015.

- ^ Waksman 2009, p. 209; Weinstein 2000, p. 44

- ^ a b c Bowar, Chad. "What Is New Wave of British Heavy Metal?". Heavy Metal 101. About.com. Retrieved 30 March 2015.

- ^ Christe 2004, p. 34; Tucker 2006, p. 173

- ^ Prato, Greg. "Budgie biography". AllMusic. Retrieved 4 April 2015.

- ^ Bushell & Halfin 1984, p. 32; Tucker 2006, p. 36

- ^ Waksman 2009, p. 209.

- ^ Christe 2004, p. 34-36.

- ^ a b c Waksman 2009, p. 197-202.

- ^ Christe 2004, pp. 40–42; Tucker 2006, p. 65

- ^ Dunn & McFadyen 2011, p. 14:40.

- ^ Macmillan 2012, p. 294-295.

- ^ Rivadavia, Eduardo. "Tygers of Pan Tang – Wild Cat review". AllMusic. Retrieved 17 June 2015.

- ^ Corich 1998.

- ^ Tucker 2006, p. 36.

- ^ Rivadavia, Eduardo. "Tank Biography". AllMusic. Retrieved 17 June 2015.

- ^ a b Rivadavia, Eduardo. "More biography". AllMusic. Retrieved 10 February 2012.

- ^ Rivadavia, Eduardo. "Atomkraft Biography". AllMusic. Retrieved 24 June 2015.

- ^ Tucker 2006, p. 178.

- ^ Christe 2004, p. 37; Waksman 2009, pp. 189–192

- ^ Christe 2004, p. 42; Moynihan & Søderlind 1998, pp. 11–14; Waksman 2009, pp. 192–195

- ^ Tucker 2006, p. 100.

- ^ Bayer 2009, p. 127-133.

- ^ Bayer 2009, p. 39-41.

- ^ Erlewine, Stephen Thomas. "Def Leppard biography". AllMusic. Retrieved 10 February 2012.

- ^ a b Rivadavia, Eduardo. "Praying Mantis biography". AllMusic. Retrieved 10 February 2012.

- ^ Rivadavia, Eduardo. "White Spirit biography". AllMusic. Retrieved 10 February 2012.

- ^ "Shy biography". AllMusic. Retrieved 10 March 2015.

- ^ Rivadavia, Eduardo. "Gaskin biography". AllMusic. Retrieved 10 March 2015.

- ^ Rivadavia, Eduardo. "Dedringer biography". AllMusic. Retrieved 13 February 2012.

- ^ Popoff 2005, pp. 96–97; Sinclair 1984

- ^ Dunn & McFadyen 2011, p. 36:30; Macmillan 2009, p. 22; Tucker 2006, pp. 129–154

- ^ Tucker 2006, pp. 129–154; Watts 1988

- ^ Popoff 2005, p. 96-97.

- ^ Rivadavia, Eduardo. "Blitzkrieg biography". AllMusic. Retrieved 10 February 2012.

- ^ Rivadavia, Eduardo. "Saracen Biography". AllMusic. Retrieved 10 March 2015.

- ^ "Shiva Biography". AllMusic. Retrieved 10 March 2015.

- ^ Rivadavia, Eduardo. "Witchfynde biography". AllMusic. Retrieved 10 February 2012.

- ^ a b Macmillan 2009, p. 526.

- ^ Rivadavia, Eduardo. "Vardis biography". AllMusic. Retrieved 10 February 2012.

- ^ "Spider Biography". AllMusic. Retrieved 10 March 2015.

- ^ a b Christe 2004, p. 40.

- ^ "Le Griffe Biography". AllMusic. Retrieved 10 March 2015.

- ^ Rivadavia, Eduardo. "Girl Biography". AllMusic. Retrieved 10 March 2015.

- ^ "Wrathchild Biography". AllMusic. Retrieved 10 March 2015.

- ^ Tucker 2006, p. 173.

- ^ Bayer 2009, p. 155.

- ^ Christe 2004, p. 36.

- ^ Bayer 2009, pp. 110–122, 127–133; Weinstein 2000, p. 40

- ^ Bayer 2009, p. 25.

- ^ Weinstein 2000, p. 37.

- ^ Weinstein 2000, p. 39.

- ^ Moynihan & Søderlind 1998, pp. 11–14; Waksman 2009, pp. 192–195

- ^ Christe 2004, p. 34; Waksman 2009, pp. 197–202

- ^ "Tour History". Thin Lizzy Guide.com. Retrieved 9 July 2015.

- ^ "UFO Concert Setlists & Tour Dates". Set lIsts.fm. Retrieved 9 July 2015.

- ^ "Judas Priest Concert Setlists & Tour Dates". Set lIsts.fm. Retrieved 9 July 2015.

- ^ Anon. 2008, p. 38:31.

- ^ Christe 2004, p. 32.

- ^ Macmillan 2009, p. 307.

- ^ Macmillan 2009, p. 446.

- ^ Macmillan 2009, p. 34.

- ^ Macmillan 2009, p. 501-502.

- ^ Macmillan 2009, p. 169.

- ^ Macmillan 2009, p. 379.

- ^ Macmillan 2009, p. 717-718.

- ^ Macmillan 2009, p. 732.

- ^ Macmillan 2009, p. 680-681.

- ^ Macmillan 2009, p. 148.

- ^ Macmillan 2009, p. 467.

- ^ Macmillan 2009, p. 663.

- ^ Macmillan 2009, p. 294.

- ^ Anon. 2008, p. 36:48.

- ^ a b Dunn & McFadyen 2011, p. 5:48.

- ^ Dunn & McFadyen 2011, p. 13:20.

- ^ Waksman 2009, p. 186-189.

- ^ Tucker 2006, p. 89; Weinstein 2000, p. 137

- ^ a b c "The Soundhouse Story part 1". HMsoundhouse.com. Retrieved 18 July 2015.

- ^ Anon. 2008, p. 31:16.

- ^ Anon. 2008, p. 32:53.

- ^ McGee 1992.

- ^ Anon. 2008.

- ^ a b "The Soundhouse Story part 2". HMsoundhouse.com. Retrieved 18 July 2015.

- ^ Considine 1990; Dunn & McFadyen 2011, p. 16:48

- ^ Waksman 2009, p. 175-181.

- ^ Barton 1979.

- ^ Kirkby 2001, p. 8:90.

- ^ Weinstein 2000, p. 24.

- ^ Roland 1984; Tucker 2006, pp. 95–102; Waksman 2009, pp. 186–189

- ^ Tucker 2006, p. 81-88.

- ^ Christe 2004, p. 34.

- ^ Fricke 1987, p. 33-35.

- ^ Tucker 2006, p. 55-56.

- ^ "Alice's Restaurant". AMFM.org.uk. Retrieved 3 May 2015.

- ^ Noble, Colin. "Colin Noble: ARfm - Our Presenters - Unsigned Show / Sunday Morning Show". ARfm. Retrieved 3 May 2015.

- ^ Dunn & McFadyen 2011, p. 13:18; Tucker 2006, p. 32

- ^ Roland 1984; Tucker 2006, pp. 95–102

- ^ Fricke 1987, pp. 25–27; Macmillan 2009, pp. 24–27; Matthews 2004, p. 33:20; Tucker 2006, pp. 120–121

- ^ Tucker 2006, p. 29.

- ^ Fricke 1987, p. 39.

- ^ Bushell & Halfin 1984, p. 31.

- ^ Bushell & Halfin 1984, p. 67.

- ^ Rivadavia, Eduardo. "Ethel the Frog biography". AllMusic. Retrieved 10 February 2012.

- ^ Rivadavia, Eduardo. "Angel Witch Biography". AllMusic. Retrieved 18 March 2015.

- ^ Tucker 2006, p. 82.

- ^ Rivadavia, Eduardo. "A II Z biography". AllMusic. Retrieved 10 February 2012.

- ^ Tucker 2006, p. 95-102.

- ^ "The Story of Samson". Book of Hours.net. Retrieved 1 July 2015.

- ^ Barton 1981a.

- ^ Ling 1999.

- ^ Macmillan 2009, p. 448.

- ^ Tucker 2006, p. 64-65, 69.

- ^ "Girlschool Official Charts". Official Charts Company. Retrieved 13 July 2015.

- ^ "Def Leppard Official Charts". Official Charts Company. Retrieved 13 July 2015.

- ^ "Tygers of Pan Tang Official Charts". Official Charts Company. Retrieved 13 July 2015.

- ^ "Iron Maiden Official Charts". Official Charts Company. Retrieved 13 July 2015.

- ^ "Saxon Official Charts". Official Charts Company. Retrieved 13 July 2015.

- ^ "Iron maiden – Running Free Live in Top of the pops". YouTube. 25 March 2007. Retrieved 13 July 2015.

- ^ "Saxon: 'Wheels of Steel', Top of the Pops 1980". YouTube. 1 May 2015. Retrieved 13 July 2015.

- ^ "Motorhead and Girlschool – Please Don't Touch (Top of the Pops)". YouTube. 6 May 2013. Retrieved 13 July 2015.

- ^ "Tygers of Pan Tang – Old Grey Whistle Test 1982". YouTube. 3 December 2010. Retrieved 13 July 2015.

- ^ Macmillan 2009, p. 520-521.

- ^ Macmillan 2009, p. 244.

- ^ Macmillan 2009, p. 647.

- ^ Macmillan 2009, p. 155-156.

- ^ Macmillan 2009, p. 371.

- ^ Macmillan 2009, p. 220.

- ^ Macmillan 2009, p. 729.

- ^ Macmillan 2009, p. 514-515.

- ^ Macmillan 2009, p. 261.

- ^ Macmillan 2009, p. 684-685.

- ^ Macmillan 2009, p. 439.

- ^ Macmillan 2009, p. 601.

- ^ Macmillan 2009, p. 81.

- ^ Macmillan 2009, p. 319-320.

- ^ Macmillan 2009, p. 608.

- ^ Thompson 2004, p. 213; Tucker 2006, pp. 30–31

- ^ Thompson 2004, p. 217-219.

- ^ Charles 1981; Popoff 2005, pp. 131–132

- ^ "Rainbow – Official Charts". Official Charts Company. Retrieved 21 April 2015.

- ^ Popoff 2005, p. 279; Thompson 2004, pp. 221–222

- ^ "Black Sabbath – Official Charts". Official Charts Company. Retrieved 21 April 2015.

- ^ Popoff 2005, p. 48-49.

- ^ Iommi & Lammers 2011.

- ^ "Michael Schenker Group – Official Charts". Official Charts Company. Retrieved 21 April 2015.

- ^ "Whitesnake – Official Charts". Official Charts Company. Retrieved 21 April 2015.

- ^ Macmillan 2009, p. 22; Sinclair 1984; Tucker 2006, pp. 129–154

- ^ Bushell & Halfin 1984, p. 78.

- ^ Bushell & Halfin 1984, p. 89.

- ^ Bushell & Halfin 1984, p. 92-93.

- ^ Fricke 1987, p. 50-55.

- ^ Sharpe-Young, Garry (2009). "Saxon". MusicMight. Retrieved 26 June 2015.

- ^ Macmillan 2009, p. 527.

- ^ Tucker 2006, p. 62-64.

- ^ "The 20th Reading Rock Festival". UKRockfestivals.com. February 2011. Retrieved 4 May 2015.

- ^ "The 21st Reading Rock Festival". UKRockfestivals.com. December 2011. Retrieved 21 June 2010.

- ^ "The 22nd Reading Rock Festival". UKRockfestivals.com. January 2012. Retrieved 4 May 2015.

- ^ Fricke 1987, p. 57; Waksman 2009, pp. 202–206

- ^ "Monsters of Rock 1980". UKRockfestivals.com. November 2013. Retrieved 4 May 2015.

- ^ "Iron Maiden – The Number of the Beast". Acclaimed Music.net. Retrieved 29 March 2015.

- ^ Bushell & Halfin 1984, pp. 77–103; Johnson 1984a

- ^ a b Tucker 2006, p. 19.

- ^ Christe 2004, p. 38; Macmillan 2012, p. 21

- ^ Christe 2004, p. 38.

- ^ Christe 2004, p. 85; Johnson 1984b

- ^ "Iron Maiden – Killers (Album)". Swedishcharts.com. Retrieved 19 July 2015.

- ^ "Infodisc.fr Note: You must select Iron Maiden". Infodisc.fr. Retrieved 19 July 2015.

- ^ "Infodisc.fr Note: You must select Saxon". Infodisc.fr. Retrieved 19 July 2015.

- ^ "Saxon – Denim and Leather (Album)". Swedishcharts.com. Retrieved 19 July 2015.

- ^ "Def Leppard – High 'N' Dry awards". AllMusic. Retrieved 19 July 2015.

- ^ "Official Albums Chart Results Matching: The Number Of The Beast". Official Charts Company. Retrieved 2 May 2015.

- ^ Popoff 2005, p. 170-171.

- ^ Barton 1980b; Tucker 2006, p. 79

- ^ Watts 1992.

- ^ Crampton 1982.

- ^ Tucker 2006, p. 81.

- ^ Macmillan 2012, p. 51-52.

- ^ Macmillan 2012, p. 672-673.

- ^ Macmillan 2012, p. 627-628.

- ^ Macmillan 2012, p. 199.

- ^ Macmillan 2012, p. 46.

- ^ Macmillan 2012, p. 489.

- ^ Kirkby 2001, p. 35:12.

- ^ Bayer 2009, p. 44; Fricke 1987, pp. 83–84; Popoff 2005, p. 92

- ^ Fricke 1987, p. 50; Waksman 2009, pp. 202–206

- ^ Fricke 1987, p. 12.

- ^ "RIAA Searchable Database: search for "Pyromania"". Recording Industry Association of America. Retrieved 22 June 2015.

- ^ Bayer 2009, p. 47; Macmillan 2012, p. 528

- ^ Rivadavia, Eduardo. "Black Rose – Boys Will Be Boys review". AllMusic. Retrieved 18 March 2015.

- ^ a b c Tucker 2006, p. 129-154.

- ^ Konow 2003, p. 133-134.

- ^ Lane 2006, p. 126.

- ^ Dunn & McFadyen 2011, p. 35:40.

- ^ Rivadavia, Eduardo. "Grim Reaper biography". AllMusic. Retrieved 10 February 2012.

- ^ Rivadavia, Eduardo (20 August 2006). "Handsome Beasts Biography". AllMusic. Retrieved 25 June 2012.

- ^ "Mammoth Biography". AllMusic. Retrieved 10 March 2015.

- ^ Tucker 2006, p. 90.

- ^ Bayer 2009, pp. 22–23; Sinclair 1984; Tucker 2006, pp. 123–124

- ^ Walser 1993, p. 120-121.

- ^ "Monsters of Rock 1987". UKRockfestivals.com. January 2012. Retrieved 4 May 2015.

- ^ "Manowar, Diamond Head, Deicide, Others To Play Metal Meltdown IV". Blabbermouth.net. 18 January 2002. Retrieved 28 August 2015.

- ^ Weinstein 2000, p. 49-50.

- ^ a b Marsicano, Dan. "What Is Power Metal?". Heavy Metal 101. About.com. Retrieved 13 July 2015.

- ^ Rivadavia, Eduardo. "Helloween Biography". AllMusic. Retrieved 8 August 2015.

- ^ a b Huey, Steve. "Savatage Biography". AllMusic. Retrieved 19 July 2015.

- ^ Erlewine, Stephen Thomas. "Metallica Biography". AllMusic. Retrieved 2 July 2015.

- ^ Huey, Steve. "Slayer Biography". AllMusic. Retrieved 2 July 2015.

- ^ Erlewine, Stephen Thomas. "Megadeth Biography". AllMusic. Retrieved 2 July 2015.

- ^ Erlewine, Stephen Thomas. "Anthrax Biography". AllMusic. Retrieved 2 July 2015.

- ^ Macmillan 2012, p. 55.

- ^ Macmillan 2012, p. 120-121.

- ^ Macmillan 2012, p. 645-646.

- ^ Macmillan 2012, p. 63.

- ^ a b Macmillan 2009, p. 24-27.

- ^ Sinclair 1984; Tucker 2006, pp. 129–154; Watts 1992

- ^ Macmillan 2009, p. 22, 528.

- ^ Rivadavia, Eduardo. "Saxon Biography". AllMusic. Retrieved 18 July 2015.

- ^ Miller 1986c; Tucker 2006, p. 101

- ^ Johnson 1986.

- ^ Macmillan 2012, p. 262-263.

- ^ Weber, Barry. "Iron Maiden Biography". AllMusic. Retrieved 20 March 2015.

- ^ Bayer 2009, p. 44.

- ^ Tucker 2006, p. 157–162, 167.

- ^ Macmillan 2012, pp. 22–23; Tucker 2006, pp. 169–172

- ^ "Kerrang! Iron Maiden Tribute Album". Metallica Official Website. 25 June 2008. Archived from the original on 28 June 2008. Retrieved 30 March 2015.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Tucker 2006, p. 163-169.

- ^ "Kerrang!'s Founding Editor To Head Up Classic Rock Magazine". Blabbermouth.net. 29 September 2004. Retrieved 14 April 2015.

- ^ Rivadavia, Eduardo. "Jaguar biography". AllMusic. Retrieved 10 February 2012.

- ^ Freeman, Phil. "Hell – Human Remains review". AllMusic. Retrieved 10 February 2012.

- ^ Moynihan & Søderlind 1998, pp. 11–14; McIver 2010, pp. 20–21

- ^ Daniels 2010, p. 83.

- ^ McIver 2006, p. 19; Miller 1986a

- ^ Bayer 2012, p. 190-191.

- ^ Dunn & McFadyen 2011, p. 42:53; Weinstein 2000, p. 44

- ^ Popoff 2014, p. 38; Tucker 2006, pp. 129–154

- ^ Moynihan & Søderlind 1998, pp. 11–14; Popoff 2005, pp. 74, 417

- ^ McIver 2006, pp. 18–22; McIver 2010, pp. 20–21; Mustaine & Layden 2010

- ^ "Speed/Thrash Metal". AllMusic. Retrieved 24 June 2015.

- ^ Christe 2004, p. 88, 92–93,108–111, 132–135.

- ^ Christe 2004, p. 136-139.

- ^ Christe 2004, p. 106.

- ^ McIver 2006, pp. 23–25, 32; Tucker 2006, pp. 41–43

- ^ "Am I Evil? by Diamond Head". Setlists.fm. Retrieved 10 August 2015.

- ^ "Power metal". AllMusic. Retrieved 17 July 2015.

- ^ Monger, James Christopher. "Manowar Biography". AllMusic. Retrieved 19 July 2015.

- ^ Reesman, Bryan. "Virgin Steele Biography". AllMusic. Retrieved 19 July 2015.

- ^ a b c Christe 2004, p. 44.

- ^ a b Christe 2004, p. 50.

- ^ DeFeis, David. "Virgin Steele Official Biography". virgin-steele.com. Retrieved 9 May 2015.

- ^ Rivadavia, Eduardo. "The Rods Biography". AllMusic. Retrieved 3 May 2015.

- ^ Barton 1981b.

- ^ Rivadavia, Eduardo. "Hellion Biography". AllMusic. Retrieved 24 June 2015.

- ^ Miller 1986b.

- ^ Hammonds 1983.

- ^ a b Macmillan 2009, p. 22.

- ^ Christe 2004, p. 44; Macmillan 2009, p. 22; Tucker 2006, pp. 129–154

- ^ Johnson 1983.

- ^ Christe 2004, p. 43.

- ^ Norton, Justin M. (2010). "Grave Digger Interview". About.com. Retrieved 26 April 2015.

- ^ Popoff 2005, p. 325.

- ^ Simmons 1986.

- ^ Rivadavia, Eduardo. "EF Band biography". AllMusic. Retrieved 10 February 2012.

- ^ "Decibel Hall of Fame – No. 74 -Mercyful Fate Melissa". Decibel. No. 78. April 2011. pp. 48–54. Retrieved 13 May 2014.

- ^ "Picture Biography". Picture official Website. Retrieved 26 April 2015.

- ^ "Bodine Biography". Regular Rocker.nl. Retrieved 26 April 2015.

- ^ "Nicko McBrain Biography, Videos & Pictures". Drum Lessons.com. Retrieved 26 April 2015.

- ^ Stein, Lior (9 April 2010). "Yves Campion (Nightmare) interview". Metal Express Radio. Retrieved 20 April 2010.

- ^ Fouce & del Val 2013, p. 128.

- ^ "Explosion Heavy en el Norte" (JPG). Heavy Rock (in Spanish). No. 10. 1982. pp. 18–22. Retrieved 26 April 2015.

- ^ "About Roadrunner Records". Roadrunner Records. Retrieved 10 August 2015.

- ^ Falckenbach, Alfie (March 2002). "Mausoleum: The story behind the legendary heavy metal label. Part I (1982–1986)". Music-Avenue.net. Archived from the original on 16 January 2011. Retrieved 22 March 2015.

{{cite web}}:|archive-date=/|archive-url=timestamp mismatch; 17 January 2011 suggested (help); Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help)

References

Bibliography

- Barton, Geoff (19 May 1979). "If You Want Blood (and Flashbombs and Dry Ice and Confetti) You Got It". Sounds. pp. 28–29.

{{cite magazine}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Barton, Geoff (July 1980). "Phil Lewis Interview". Sounds.

- Barton, Geoff (4 October 1980). "Scrap Metal". Sounds. p. 39.

- Barton, Geoff (September 1981). "The Night of the Demon". Kerrang!. No. 3. pp. 6–7.

- Barton, Geoff (September 1981). "Armed & Ready". Kerrang!. No. 3. p. 12.

- Bayer, Gerd; et al. (2009). Heavy Metal Music in Britain. Farnham, Surrey, UK: Ashgate Publishing. ISBN 978-0-7546-6423-9.

{{cite book}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|last1=(help); Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Bushell, Garry; Halfin, Ross (1984). Iron Maiden – Running Free. London, UK: Zomba Books. ISBN 978-0-946391-50-9.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Charles, D. W. (December 1981). "Captain Gillan". Kerrang!. No. 6. pp. 10, 12.

{{cite magazine}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Christe, Ian (2004). Sound of the Beast: The Complete Headbanging History of Heavy Metal. New York City: HarperCollins. ISBN 978-0-380-81127-4.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help); Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Considine, J. D. (15 November 1990). "Metal Mania". Rolling Stone. No. 591. pp. 100–104.

{{cite magazine}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Corich, Robert M. (1998). The Collection (CD booklet). Girlschool. England: Sanctuary Records (CMDD014).

{{cite AV media notes}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|titlelink=(help); Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Crampton, Luke (30 December 1982). "Best Sellers of 1982". Kerrang!. No. 32. p. 3.

{{cite magazine}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Daniels, Neil (2010). The Story of Judas Priest: Defenders of the Faith. New York City: Omnibus Press. ISBN 978-1-84772-707-7.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Jeffrey, Dunn (30 December 1982). "Kwotes of the Year". Kerrang!. No. 32. p. 13.

We don't do gigs, we do shows. It's fucking massive. If you stand at the front of the stage you're gonna get your head blown off!

- Fouce, Héctor; del Val, Feràn (2013). "From el Rollo to Heavy Metal". In Martinez, Sìlvia; Fouce, Héctor (eds.). Made in Spain: Studies in Popular Music. New York City: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-203-12703-2. Retrieved 26 April 2015.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Fricke, David (1987). Animal Instinct: The Def Leppard Story. London, UK: Zomba Books. ISBN 0-946391-55-6.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Hammonds, Steve (August 1983). "Exciter" (PDF). Metal Forces. No. 1. p. 33. Retrieved 3 July 2015.

{{cite magazine}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Hatch, David; Millward, Stephen (1987). "After the Flood". From Blues to Rock: An Analytical History of Pop Music. Manchester, UK: Manchester University Press. ISBN 0-7190-1489-1. Retrieved 17 October 2015.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Iommi, Tony; Lammers, T. J. (2011). "Bill goes to shits". Iron Man: My Journey through Heaven and Hell with Black Sabbath. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Da Capo Press. ISBN 978-0-306-82054-0.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Johnson, Howard (19 May 1983). "Warning from Tokyo". Kerrang!. No. 42. pp. 24–26.

{{cite magazine}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Johnson, Howard (5 April 1984). "Don't Fear the Reaper...". Kerrang!. No. 65. p. 11.

- Johnson, Howard (1984). "The Big Read". Extra Kerrang!. No. 1. p. 38.

- Johnson, Howard (30 October 1986). "Hear No Evil". Kerrang!. No. 132. pp. 10–11.

{{cite magazine}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Johnson, Rick (October 1979). "Is Heavy Metal Dead? Last Drum Solo at the Power Chord Corral". Creem. Vol. II, no. 5.

{{cite magazine}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Kilmister, Ian; Garza, Janiss (2004). White Line Fever. New York City: Simon & Schuster. ISBN 0-684-85868-1.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Konow, David (2 January 2003). Bang Your Head: The Rise and Fall of Heavy Metal. New York City: Three Rivers Press. ISBN 978-0-609-80732-3. Retrieved 24 June 2015.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Lane, Frederick S. (2006). The Decency Wars: The Campaign to Cleanse American Culture. Amherst, New York: Prometheus Books. ISBN 1-59102-427-7.

- Ling, Dave (18 December 1999). "Interview with Gerry Bron". Classic Rock. No. 9.

{{cite magazine}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Macmillan, Malc (2012). The New Wave of British Heavy Metal Encyclopedia (3 ed.). Berlin, Germany: I.P. Verlag Jeske/Mader GbR. ISBN 978-3-931624-16-3.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help); Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Makowski, Pete (9 August 1980). "Back to Schooldays". Sounds. Retrieved 3 January 2011.

{{cite magazine}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - McGee, Hal (2 June 1992). "Cause and Effect". In James, Robin (ed.). Cassette Mythos. New York City: Autonomedia. ISBN 978-0-936756-69-1.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - McIver, Joel (9 January 2006). Justice for All: The Truth About Metallica (2 ed.). London, UK: Omnibus Press. ISBN 978-1-84449-828-4.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - McIver, Joel (1 October 2010). The Bloody Reign of Slayer (2 ed.). London, UK: Omnibus Press. ISBN 978-1-84938-386-8.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Millar, Robbi (1 March 1980). "The Dinosaur's Daughters". Sounds. pp. 170–171. Retrieved 30 December 2010.

{{cite magazine}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Miller, Paul (1986). "UK Dekay?". Mega Metal Kerrang!. No. 1. pp. 30–31.

- Miller, Paul (1986). "The Men from Ungol". Mega Metal Kerrang!. No. 4. pp. 18–19.

- Miller, Paul (1986). "The Madder They Come...". Mega Metal Kerrang!. No. 4. p. 29.

- Moynihan, Michael; Søderlind, Difdrik (1998). Lords of Chaos – The Bloody Rise of the Satanic Metal Underground. Port Townsend, Washington, USA: Feral House. ISBN 0-922915-48-2.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Mustaine, Dave; Layden, Joe (2010). "Lars and Me, or What Am I Getting Myself Into?". Mustaine – A Heavy Metal Memoire. New York City: Harper Collins. ISBN 978-0-06-199703-7.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Popoff, Martin (1 November 2005). The Collector's Guide to Heavy Metal: Volume 2: The Eighties. Burlington, Ontario, Canada: Collector's Guide Publishing. ISBN 978-1-894959-31-5.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Popoff, Martin (15 August 2014). The Big Book of Hair Metal: The Illustrated Oral History of Heavy Metal's Debauched Decade. Voyageur Press. ISBN 978-0-7603-4546-7.

- Roland, Paul (1984). "The State of Independents". Extra Kerrang!. No. 1. pp. 23, 24, 26, 46.

{{cite magazine}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Simmons, Sylvie (1986). "'Lock Jaw". Mega Metal Kerrang!. No. 4. pp. 8–11.

{{cite magazine}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Sinclair, David (5 April 1984). "Only the Strong Survive". Kerrang!. No. 65. p. 29.

{{cite magazine}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Smith, Richard (11 May 1978). "Will Heavy Metal Survive the Seventies?". Circus. No. 181.

{{cite magazine}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Thompson, Dave (August 2004). Smoke on the Water: The Deep Purple Story. Toronto, Canada: ECW Press. ISBN 978-1-55022-618-8. Retrieved 25 December 2013.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Tucker, John (2006). Suzie Smiled... The New Wave of British Heavy Metal. Shropshire, UK: Independent Music Press. ISBN 978-0-9549704-7-5.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Waksman, Steve (2009). This Ain't the Summer of Love: Conflict and Crossover in Heavy Metal and Punk. Berkeley, California: University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-94388-9. Retrieved 8 January 2014.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Walser, Robert (15 May 1993). Running with the Devil: Power, Gender, and Madness in Heavy Metal Music. Middletown, Connecticut: Wesleyan University. ISBN 978-0-8195-6260-9. Retrieved 6 April 2015.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Watts, Chris (19 November 1988). "Once Bitten... Twice Dry". Kerrang!. No. 214. pp. 28–29.

{{cite magazine}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Watts, Chris (19 December 1992). "Where Are They Now?". Kerrang!. No. 423. pp. 36–37.

{{cite magazine}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Weinstein, Deena (2000). Heavy Metal: The Music and Its Culture. Da Capo Press. ISBN 978-0-306-80970-5. Retrieved 8 January 2014.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Welch, Chris (1988). Black Sabbath. Bobcat Books. ISBN 0-7119-1738-8.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Zarnowitz, Victor; Moore, Geoffrey H. (October 1977). "The Recession and Recovery of 1973–1976". Explorations in Economic Research, Volume 4, number 4 (PDF). National Bureau of Economic Research. pp. 1–87. Retrieved 26 October 2015.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)

Filmography

- Anon. (2008). Iron Maiden and the New Wave of British Heavy Metal (Documentary). New Malden, UK: Prism Films. ASIN B0016GLZ4M.

{{cite AV media}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Dunn, Sam; McFadyen, Scot; Wise, Jessica Joy (2005). Metal: A Headbanger's Journey (Documentary). Canada: Seville Pictures. ASIN B000EGEJIY.

{{cite AV media}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Dunn, Sam; McFadyen, Scot (10 December 2011). "New Wave of British Heavy Metal". Metal Evolution (Documentary). Toronto, Canada: Banger Films, Inc. ASIN B007GFYC0Q.

{{cite AV media}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Kirkby, Tim (26 November 2001). Classic Albums: Iron Maiden – The Number of the Beast (Documentary). London, UK: Isis Productions / Eagle Vision. ASIN B00005QJIA.

{{cite AV media}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Matthews, Amos (8 November 2004). The History of Iron Maiden – Part 1: The Early Days (Documentary). London, UK: EMI. ASIN B0006B29Z2.

{{cite AV media}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)