Norwegian phonology

This article needs additional citations for verification. (January 2010) |

The sound system of Norwegian resembles that of Swedish. There is considerable variation among the dialects, and all pronunciations are considered by official policy to be equally correct.[1] The variant generally taught to foreign students is the so-called Standard Eastern Norwegian or Standard Østnorsk, loosely based on the speech of the literate classes of the Oslo area.[2] Despite not being an official standard, as Norwegian does not have an official standard, it has traditionally been used in public venues such as theatre and TV, although today local dialects are used extensively in spoken and visual media.[2]

This article describes the phonology of Standard Østnorsk.

Consonants

| Labial | Dental/ Alveolar |

Retroflex | Dorsal | Glottal | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nasal | m | n | ŋ | |||||

| Stop | p | b | t | d | k | ɡ | ||

| Fricative | f | s | ʂ | ɕ | h | |||

| Approximant | ʋ | l (ɫ) | j | |||||

| Flap | ɾ | ɽ | ||||||

/t d n l/ are laminal denti-alveolar [t̪ d̪ n̪ l̪] in Standard Eastern Norwegian, and apical alveolar [t̺ d̺ n̺ l̺] in the South West. /ɾ/ is an apical alveolar flap, but sometimes it can be trilled.

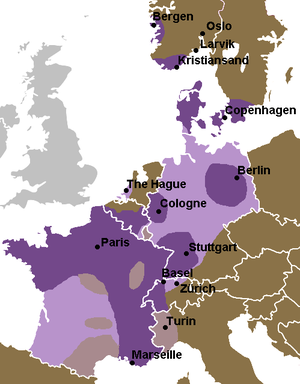

Most of the retroflex (and postalveolar) consonants are mutations of [ɾ]+any other alveolar/dental consonant; rn /ɾn/ > [ɳ], rt /ɾt/ > [ʈ], rl /ɾl/ > [ɭ], rs /ɾs/ > [ʂ], etc. /ɾd/ across word boundaries (“sandhi”), in loanwords and in a group of primarily literary words may be pronounced [ɾd], e.g., verden [ˈʋæɾdn̩], but it may also be pronounced [ɖ] in some dialects. Most of the dialects in Eastern, Central and Northern Norway use the retroflex consonants. Most Southern and Western dialects do not have these retroflex sounds, because in these areas a guttural realization of the /r/ phoneme is commonplace, and seems to be expanding. Depending on phonetic context voiceless ([χ]) or voiced uvular fricatives ([ʁ]) are used. (See map at right.) Other possible pronunciations include a uvular approximant [ʁ̞] or, more rarely, a uvular trill [ʀ]. There is, however, a small number of dialects that use both the uvular /r/ and the retroflex allophones.

The retroflex flap, [ɽ], colloquially known to Norwegians as tjukk l ("thick l"), is a Central Scandinavian innovation that exists in Eastern Norwegian (including trøndsk), the southmost Northern dialects, and the most eastern Western Norwegian dialects. It is supposedly non-existent in most Western and Northern dialects. Today there is doubtlessly distinctive opposition between /ɽ/ and /l/ in the dialects that do have /ɽ/, e.g. gard /gɑ:ɽ/ 'farm' and gal /gɑ:l/ 'crazy' in many Eastern Norwegian dialects. Although traditionally an Eastern Norwegian dialect phenomenon, it was considered vulgar, and for a long time it was avoided. Nowadays it is considered standard in the Eastern and Central Norwegian dialects,[4] but is still clearly avoided in high prestige sociolects or standardized speech. This avoidance calls into question the status of /ɽ/ as a phoneme in certain sociolects.

Some speakers (especially in Bergen (where it is an established dialect phenomenon) and Oslo) do not use the voiceless alveolo-palatal fricative, using instead the voiceless retroflex fricative /ʂ/ in contexts where the voiceless alveolo-palatal fricative would commonly be used. This is a development which seem to be on the rise in spoken Norwegian.[5]

Another allophone of /l/, in addition to being the standard pronunciation of it in some dialects of Norwegian, the velarized alveolar lateral approximant [ɫ] (also known as “dark L”) appears after [ɑ], [oː] and [ɔ], except when followed by a stressed vowel, where the /l/ connects to its succeeding syllable and thus the standard [l] is used: ball [bɑɫː] (“ball”), påle [²pʰɔɫːə] (“pole”), fotball [ˈfut̚ːb̥ɑɫ] (“football”); but palass [pɑˈlɑsː] (“palace”).

The voiceless stops are typically aspirated.

Some loanwords and onomatopoeia may be pronounced with sounds not used in proper Norwegian words: gin [dʒɪn], wow! [wæ:w] and bzzzzz! [bzːːː] (imitation of the sound of a bee).[citation needed]

Vowels

Unless preceding another vowel, all unstressed vowels are short.[6]

| Diphthongs[7] | Monophthongs[8] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

- Notes

- /ɑ ɑː/ are open central unrounded [ɑ̈ ɑ̈ː],[9][10] but /ɑ/ may be somewhat fronted [ɑ̟̈][11] or retracted [ɑ̠̈].[11] For older speakers they can be front [a aː].[12]

- /ɑɪ/ has a central starting point [ɑ̈ɪ].[13][14] Sometimes /ɪ/ is realized as [j],[14] especially in emphatic pronunciation.[14]

- /æɪ/ is pronounced [æɪ],[13][14] but some, especially older speakers pronounce it [eɪ].[14] Sometimes /ɪ/ is realized as [j],[14] especially in emphatic pronunciation.[14]

- /eː/ is front unrounded[10][16] and has been variously described as close-mid [eː][10] and mid [e̞ː].[16] It is frequently diphthongized to [eə].[17]

- /œ/ is rounded and centralized[10][18] and has been variously described as open-mid [œ̈][10] and mid [œ̝̈].[18]

- /œʏ/ has a centralized starting point: [œ̈ʏ].[15][14] Sometimes /ʏ/ is realized as [j],[14] especially in emphatic pronunciation.[19]

- /øː/ is rounded and centralized[10][18] and has been variously described as close-mid [ø̈ː][10] and mid [ø̞̈ː].[18] It is frequently diphthongized to [øə].[20]

- /ɔ/ is rounded and centralized[10][21] and has been variously described as near-open [ɒ̝̈][10] and open-mid [ɔ̈].[21]

- /ɔʏ/ has a starting point that has been variously described as centralized near-open [ɒ̝̈ʏ][14] or back open-mid [ɔʏ].[15] Sometimes /ʏ/ is realized as [j],[14] especially in emphatic pronunciation.[19]

- /ɪ/ is front unrounded,[10][16] and has been variously described as near-close [ɪ̟][10] and close [i].[16]

- /ʏ/ is near-close rounded[10][18] and has been variously described as front [ʏ̟][10] and near-front [ʏ].[18]

- /yː/ is rounded[10][18] and has been variously described as close front [yː][10] and near-close near-front [ʏː].[18] It can be diphthongized to [yə].[23]

- /ʉ/ is rounded[10][24] and has been variously described as near-close near-front [ʏ][10] and close central [ʉ].[24]

- /ʉː/ is close rounded[10][24] and has been variously described as near-front [ʉ̟ː][10] and central [ʉː].[24]

- /u/ is rounded[10][25] and has been variously described as near-close near-back [ʊ][10] and close back [u].[25]

In almost all other Wikipedia articles the diacritics are omitted. They're shown here for the sake of clarity. /yː/ is protruded, [iʷ], whereas /ʉː/ and /uː/ are compressed, [ɨᵝ], [ɯᵝ].[citation needed]

There are also a few diphthongs that can be analyzed as sequences of a short vowel and a glide: /ej/, /œj/, and /ɛw/. The diphthongs /ɔj/ and /ɑj/ only appear in loanwords - and /ʉj/ in just one single word (hui).[6] Vanvik (1979) analyzes them as diphthongs, which he writes /æi øy æʉ ɔy ai/. His diphthong chart,[14] however, clearly shows that /øy/ has an open-mid near-front starting point [œ̈].

The phonemic status of long and short [æ] in Standard Eastern Norwegian is unclear since it patterns as an allophone of /eː/ and /ɛ/ before liquid consonants and approximants, though the introduction of loanwords has created some contrasts before /j/ such as tape [tɛjp] ('tape') vs. sleip [ʂɭæjp] ('slimy')[26] and minimal pairs like hacke [ˈhækə] ('to hack', from English) vs. hekke [ˈhɛkə] ('to nest'). [ə] only occurs in unstressed syllables.[27]

Accent

Norwegian is a pitch accent language with two distinct pitch patterns. They are used to differentiate two-syllable words with otherwise identical pronunciation. For example in most Norwegian dialects, the word "bønder" (farmers) is pronounced using tone 1, while "bønner" (beans or prayers) uses tone 2. Though the difference in spelling occasionally allow the words to be distinguished in written language, in most cases the minimal pairs are written alike, since written Norwegian has no explicit accent marks.

There are significant variations in the realization of the pitch accent between dialects. In most of Eastern Norway, including the capital Oslo, the so-called low pitch dialects are spoken. In these dialects, accent 1 uses a low flat pitch in the first syllable, while accent 2 uses a high, sharply falling pitch in the first syllable and a low pitch in the beginning of the second syllable. In both accents, these pitch movements are followed by a rise of intonational nature (phrase accent), the size (and presence) of which signals emphasis/focus and which corresponds in function to the normal accent in languages that lack lexical tone, such as English. That rise culminates in the final syllable of an accentual phrase, while the fall to utterance-final low pitch that is so common in most languages[28] is either very small or absent.

On the other hand, in most of western and northern Norway (the so-called high-pitch dialects) accent 1 is falling, while accent 2 is rising in the first syllable and falling in the second syllable or somewhere around the syllable boundary. The two tones can be transcribed on the first vowel as /à/ for accent 1 and /â/ for accent 2; the modern reading of the IPA (low and falling) corresponds to eastern Norway, whereas an older tradition of using diacritics to represent the shape of the pitch trace (falling and rising-falling) corresponds to western Norway.

The pitch accents (as well as the peculiar phrase accent in the low-tone dialects) give the Norwegian language a "singing" quality which makes it fairly easy to distinguish from other languages. Interestingly, accent 1 generally occurs in words that were monosyllabic in Old Norse, and accent 2 in words that were polysyllabic.

Tonal accents and morphology

In many dialects, the accents take on a significant role in marking grammatical categories. Thus, the ending (T1)—en implies determinate form of a masculine monosyllabic noun ([båten, bilen, (den store) skjelven] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help)), whereas (T2)-en denotes either determinate form of a masculine bisyllabic noun or an adjectivised noun/verb ([(han var) skjelven, moden] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help)). Similarly, the ending (T1)—a denotes feminine singular determinate monosyllabic nouns ([boka, rota] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help)) or neutrum plural determinate nouns ([husa, lysa] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help)), whereas the ending (T2)—a denotes the preterite of weak verbs ([rota, husa] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help)), feminine singular determinate bisyllabic nouns ([bøtta, ruta, jenta] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help)).

In compound words

In a compound word, the pitch accent is lost on one of the elements of the compound (the one with weaker or secondary stress), but the erstwhile tonic syllable retains the full length (long vowel or geminate consonant) of a stressed syllable.[29]

Monosyllabic tonal accents

In some dialects of Norwegian, mainly those from Nordmøre and Trøndelag to Lofoten, there may also be tonal opposition in monosyllables, as in [bîːl] ('car') vs. [bìːl] ('axe'). In a few dialects, mainly in and near Nordmøre, the monosyllabic tonal opposition is also represented in final syllables with secondary stress, as well as double tone designated to single syllables of primary stress in polysyllabic words. In practice, this means that one gets minimal pairs like: [hɑ̀ːniɲː] ('the rooster') vs. [hɑ̀ːnîɲː] ('get him inside'); [brŷɲːa] ('in the well') vs. [brŷɲːâ] ('her well'); [læ̂nsmɑɲː] ('sheriff') vs. [læ̂nsmɑ̂ɲː] ('the sheriff'). Amongst the various views on how to interpret this situation, the most promising one may be that the words displaying these complex tones have an extra mora. This mora may have little or no effect on duration and dynamic stress, but is represented as a tonal dip.

Other dialects with tonal opposition in monosyllabic words have done away with vowel length opposition. Thus, the words [vɔ̀ːɡ] ('dare') vs. [vɔ̀ɡː] ('cradle') have merged into [vɔ̀ːɡ] in the dialect of Oppdal.

Loss of tonal accents

Some forms of Norwegian have lost the tonal accent opposition. This includes mainly parts of the area around (but not including) Bergen; the Brønnøysund area; to some extent, the dialect of Bodø; and, also to various degrees, many dialects between Tromsø and the Russian border. Faroese and Icelandic, which have their main historical origin in Old Norse, also show no tonal opposition. It is, however, not clear whether these languages lost the tonal accent or whether the tonal accent was not yet there when these languages started their separate development. Danish (apart from some southern dialects) and Finland Swedish also have no tonal opposition.

Pulmonic ingressive

The word ja "yes" is sometimes pronounced with inhaled breath (pulmonic ingressive) in Norwegian — and this can be rather confusing for foreigners. The exact same phenomenon occurs in Danish, Icelandic and Swedish too, and can also be found in German and Finnish.

Sample

The sample text is a reading of The North Wind and the Sun by a 47-year-old professor from Oslo's Nordstrand district.[30]

Phonemic transcription

/²nuːɾɑˌʋɪnən ɔ ˈsuːlən ²kɾɑŋlət ɔm ʋɛm ɑː dɛm səm ˈʋɑːɾ dən ²stæɾkəstə || ˌdɑː ˈkɔm deː ən ˈmɑn ˌgoːənə meː ən ˈʋɑɾm ˈfɾɑk pɔ ˌsæ || diː bleː ²eːnjə ɔm ɑt ˈdɛn səm ˈfœʂt ˌkʉnə fɔ ˈmɑnən tɔ ²tɑː ɑː sæ ˈfɾɑkən ˌskʉlə ²jɛlə fɔɾ dən ²stæɾkəstə ɑː ˌdɛm || ˈsoː ²bloːstə ²nuːɾɑˌʋɪnən ɑː ˈɑl sɪn ˈmɑkt | mɛn ju ˈmeːɾ han ²bloːstə | ju ²tɛtəɾə ˌtɾɑk ˈmɑnən ˈfɾɑkən ˈɾʉnt sæ | ɔ tə ˈsɪst ˌmɔtə ²nuːɾɑˌʋɪnən ²jiː ˌɔp || ˌdɑː ²ʂɪntə ˈsuːlən ˈfɾɛm ˌsoː ˈgɔt ɔ ˈʋɑɾmt ɑt ˈmɑnən ˈstɾɑks ˌmɔtə ²tɑː ɑː sæ ˈfɾɑkən || ɔ ˈsoː ˌmɔtə ²nuːɾɑˌʋɪnən ˈɪnˌɾœmə ɑt ˈsuːlən ˈʋɑːɾ ən ²stæɾkəstə ɑː ˈdɛm/

Phonetic transcription

[²nuːɾɑˌʋɪnˑn̩ ɔ ˈsuːln̩ ²kɾɑŋlət ɔm ʋɛm ɑ dɛm sɱ̍ ˈʋɑː ɖɳ̩ ²stæɾ̥kəstə || ˌdɑˑ ˈkʰɔmː de n ˈmɑnː ˌgoˑənə me n ˈʋɑɾm ˈfɾɑkː pɔ ˌsæ || di ble ²eːnjə ɔm ɑt ˈdɛnː sɱ̍ ˈfœʂt̠ ˌkʰʉnˑə fɔ ˈmɑnːn̩ tɔ ²tʰɑː ɑ sæ ˈfɾɑkːən ˌskʉlˑə ²jɛlːə fɔ ɖɳ̩ ²stæɾkəstə ɑː ˌdɛmˑ || ˈsoː ²bloːstə ²nuːɾɑˌʋɪnːn̩ ɑ ˈʔɑlː sɪn ˈmɑkʰtʰ | mɛn ju ˈmeːɾ ɦam ²bloːstə | ju ²tʰɛtːəɾə ˌtɾɑkˑ ˈmɑnːn̩ ˈfɾɑkːən ˈɾʉnt sæ | ɔ tə ˈsɪst ˌmɔtˑə ²nuːɾɑˌʋɪnˑn̩ ²jiː ˌɔpʰ || ˌdɑː ²ʂɪntə ˈsuːln̩ ˈfɾɛm ˌsoˑ ˈgɔtʰː ɔ ˈʋɑɾmtʰ ɑt̚ ˈmɑnːən ˈstɾɑks ˌmɔtˑə ²tɑː ɑ sæ ˈfɾɑkːən || ɔ ˈsoː ˌmɔtˑə ²nuːɾɑˌʋɪnˑn̩ ˈɪnːˌɾœmˑə ɑt ˈsuːln̩ ˈʋɑːɾ n̩ ²stæɾ̥kəstə ʔɑ ˈdɛmː][31]

Orthographic version

Nordavinden og solen kranglet om hvem av dem som var den sterkeste. Da kom det en mann gående med en varm frakk på seg. De blei enige om at den som først kunne få mannen til å ta av seg frakken skulle gjelde for den sterkeste av dem. Så blåste nordavinden av all si makt, men jo mer han blåste, jo tettere trakk mannen frakken rundt seg, og til sist måtte nordavinden gi opp. Da skinte solen fram så godt og varmt at mannen straks måtte ta av seg frakken. Og så måtte nordavinden innrømme at solen var den sterkeste av dem.

See also

Notes

- ^ Kristoffersen (2007:6)

- ^ a b Kristoffersen (2007:7)

- ^ Map based on Trudgill (1974:221)

- ^ Kristoffersen (2007:6–11)

- ^ Språkrådet: Fonetisk perspektiv på sammenfallet av sj-lyden og kj-lyden i norsk (in Norwegian)

- ^ a b Kristoffersen (2007:19)

- ^ Diphthongs chart is from Vanvik (1979:22).

- ^ Monophthongs chart is from Vanvik (1979:13).

- ^ a b Strandskogen (1979), pp. 15 and 18.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa Vanvik (1979), p. 13.

- ^ a b Vanvik (1979), p. 16.

- ^ Vanvik (1979), p. 15-16.

- ^ a b Strandskogen (1979), pp. 25.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m Vanvik (1979), p. 22.

- ^ a b c Strandskogen (1979), pp. 26.

- ^ a b c d e f Strandskogen (1979), pp. 15–16.

- ^ a b Vanvik (1979), p. 14.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Strandskogen (1979), pp. 15 and 23.

- ^ a b Vanvik (1979), p. 23.

- ^ Vanvik (1979), p. 20.

- ^ a b c Strandskogen (1979), pp. 15 and 19.

- ^ a b Vanvik (1979), p. 17.

- ^ Vanvik (1979), p. 19.

- ^ a b c d Strandskogen (1979), pp. 15 and 21.

- ^ a b c Strandskogen (1979), pp. 15 and 20.

- ^ Kristoffersen (2007:14)

- ^ Kristoffersen (2007:20)

- ^ Gussenhoven (2004:89)

- ^ Kristoffersen (2007:184)

- ^ "Nordavinden og sola: Opptak og transkripsjoner av norske dialekter".

- ^ Source of the narrow transcription: "Nordavinden og sola: Opptak og transkripsjoner av norske dialekter". Some symbols were changed to fit the ones used in this article.

References

- Gussenhoven, Carlos (2004), The Phonology of Tone and Intonation, Cambridge University Press

- Kristoffersen, Gjert (2007), The Phonology of Norwegian, Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-19-823765-5

- Strandskogen, Åse-Berit (1979), Norsk fonetikk for utlendinger, Oslo: Gyldendal, ISBN 82-05-10107-8

- Trudgill, Peter (1974), "Linguistic change and diffusion: Description and explanation in sociolinguistic dialect", Language in Society, 3 (2): 215–246, doi:10.1017/S0047404500004358

- Vanvik, Arne (1979), Norsk fonetikk, Oslo: Universitetet i Oslo, ISBN 82-990584-0-6