Palace of Versailles

This article includes a list of general references, but it lacks sufficient corresponding inline citations. (September 2016) |

| Palace of Versailles | |

|---|---|

Château de Versailles | |

Aerial view of the Palace from above the Gardens of Versailles | |

Location within Île-de-France | |

| General information | |

| Location | Versailles, France |

| Coordinates | 48°48′16″N 2°07′23″E / 48.804404°N 2.123162°E |

| Technical details | |

| Floor area | 67,000 m2 (721,182 ft2) |

| Official name | Palace and Park of Versailles |

| Type | Cultural |

| Criteria | i, ii, vi |

| Designated | 1979 (3rd session) |

| Reference no. | 83 |

| State Party | France |

| Region | Europe |

The Palace of Versailles, Château de Versailles, or simply Versailles (English: /vɛərˈsaɪ/ vair-SY or /vərˈsaɪ/ vər-SY; French: [vɛʁsaj]), is a royal château in Versailles in the Île-de-France region of France.

When the château was built, Versailles was a small village dating from the 11th century; today, however, it is a wealthy suburb of Paris, some 20 kilometres (12 miles) southwest of the centre of the French capital (point zero at square in front of Notre Dame). Versailles was the seat of political power in the Kingdom of France from 1682, when Louis XIV moved the royal court from Paris, until the royal family was forced to return to the capital in October 1789, within three months after the beginning of the French Revolution. Versailles is therefore famous not only as a building, but as a symbol of the system of absolute monarchy of the Ancien Régime.

History

Architectural history

17th century

First built by Louis XIII in 1623 as a hunting lodge of brick and stone, the edifice was enlarged into a royal palace by Louis XIV. The first phase of the expansion (c. 1661–1678) was designed and supervised by the architect Louis Le Vau. It culminated in the addition of three new wings of stone (the enveloppe), which surrounded Louis XIII's original building on the north, south, and west (the garden side). After Le Vau's death in 1670, the work was taken over and completed by his assistant, François d'Orbay.[1] Charles Le Brun designed and supervised the elaborate interior decoration, and André Le Nôtre landscaped the extensive Gardens of Versailles. Le Brun and Le Nôtre collaborated on the numerous fountains, and Le Brun supervised the design and installation of countless statues.[2]

During the second phase of expansion (c. 1678–1715), two enormous wings north and south of the wings flanking the Cour Royale (Royal Courtyard) were added by the architect Jules Hardouin-Mansart. He also replaced Le Vau's large terrace, facing the garden on the west, with what became the most famous room of the palace, the Hall of Mirrors. Mansart also built the Petites Écuries and Grandes Écuries (stables) across the Place d'Armes, on the eastern side of the château, and, in 1687, the Grand Trianon, or Trianon de Marbre (Marble Trianon), replacing Le Vau's 1668 Trianon de Porcelaine in the northern section of the park. Work was sufficiently advanced by 1682, that Louis XIV was able to proclaim Versailles his principal residence and the seat of the government of the Kingdom of France, and also to give rooms in the palace to almost all of his courtiers. After the death of his consort Maria Theresa of Spain in 1683, Louis XIV undertook the enlargement and remodeling of the royal apartments in the original part of the palace, the former hunting lodge built by his father. The Royal Chapel of Versailles, located at the south end of the north wing, was begun by Mansart in 1688, and after his death in 1708, completed by his assistant Robert de Cotte in 1710.[3]

Cost

One of the most baffling aspects to the study of Versailles is the cost – how much Louis XIV and his successors spent on Versailles. Owing to the nature of the construction of Versailles and the evolution of the role of the palace, construction costs were essentially a private matter. Initially, Versailles was planned to be an occasional residence for Louis XIV and was referred to as the "king's house".[4] Accordingly, much of the early funding for construction came from the king's own purse, funded by revenues received from his appanage as well as revenues from the province of New France (Canada), which, while part of France, was a private possession of the king and therefore exempt from the control of the Parliaments.[5]

Once Louis XIV embarked on his building campaigns, expenses for Versailles became more of a matter for public record, especially after Jean-Baptiste Colbert assumed the post of finance minister. Expenditures on Versailles have been recorded in the compendium known as the Comptes des bâtiments du roi sous le règne de Louis XIV and which was edited and published in five volumes by Jules Guiffrey in the 19th century. These volumes provide valuable archival material pursuant to the financial expenditures of all aspects of Versailles from the payments disbursed for many trades as varied as artists and mole catchers.[6]

To counter the costs of Versailles during the early years of Louis XIV's personal reign, Colbert decided that Versailles should be the "showcase" of France.[7] Accordingly, all materials that went into the construction and decoration of Versailles were manufactured in France. Even the mirrors used in the decoration of the Hall of Mirrors were made in France. While Venice in the 17th century had the monopoly on the manufacture of mirrors, Colbert succeeded in enticing a number of artisans from Venice to make the mirrors for Versailles. However, owing to Venetian proprietary claims on the technology of mirror manufacture, the Venetian government ordered the assassination of the artisans to keep the secrets proprietary to the Venetian Republic.[7] To meet the demands for decorating and furnishing Versailles, Colbert nationalised the tapestry factory owned by the Gobelin family, to become the Manufacture royale des Gobelins.[7]

In 1667, the name of the enterprise was changed to the Manufacture royale des Meubles de la Couronne. The Gobelins were charged with all decoration needs of the palace, which was under the direction of Charles Le Brun/[7]

One of the most costly elements in the furnishing of the Grands appartements during the early years of the personal reign of Louis XIV was the silver furniture, which can be taken as a standard – with other criteria – for determining a plausible cost for Versailles. The Comptes meticulously list the expenditures on the silver furniture – disbursements to artists, final payments, delivery – as well as descriptions and weight of items purchased. Entries for 1681 and 1682 concerning the silver balustrade used in the salon de Mercure serve as an example:

- Year 1681

II. 5 In anticipation: For the silver balustrade for the king's bedroom: 90,000 livres

II. 7 18 November to Sieur du Metz, 43,475 livres 5 sols for delivery to Sr. Lois and to Sr. de Villers for payment of 142,196 livres for the silver balustrade that they are making for the king's bedroom and 404 livres for tax: 48,861 livres 5 sol.

II. 15 16 June 1681 – 23 January 1682 to Sr. Lois and Sr. de Villers silversmiths on account for the silver balustrade that they are making for the king's use (four payments): 88,457 livres 5 sols.

II. 111 25 March – 18 April to Sr. Lois and Sr. de Villers silversmiths who are working on a silver balustrade for the king, for continued work (two payments): 40,000 livres

- Year 1682

II. 129 21 March to Sr. Jehannot de Bartillay 4,970 livres 12 sols for the delivery to Sr. Lois and de Villers silversmiths for, with 136,457 livres 5 sol to one and 25,739 livres 10 sols to another, making the 38 balusters, 17 pilasters, the base and the cornice for the balustrade for the château of Versailles weighing 4,076 marc at the rate of 41 livres the marc[a] including 41 livres 2 sols for tax: 4,970 livres 12 sols.[6]

Accordingly, the silver balustrade, which contained in excess of one ton of silver, cost in excess of 560,000 livres. It is difficult – if not impossible – to give an accurate rate of exchange between 1682 and today.[b] However, Frances Buckland provides valuable information that provides an idea of the true cost of the expenditures at Versailles during the time of Louis XIV. In 1679, Mme de Maintenon stated that the cost of providing light and food for twelve people for one day amounted to slightly more than 14 livres.[8] In December 1689, to defray the cost of the War of the League of Augsburg, Louis XIV ordered all the silver furniture and articles of silver at Versailles—including chamber pots—sent to the mint to be melted.[9]

Clearly, the silver furniture alone represented a significant outlay in the finances of Versailles. While the decoration of the palace was costly, certain other costs were minimised. For example, labour for construction was often low, due largely to the fact that the army during times of peace and during the winter, when wars were not waged, was pressed into action at Versailles. Additionally, given the quality and uniqueness of the items produced at the Gobelins for use and display at Versailles, the palace served as a venue to showcase not only the success of Colbert's mercantilism, but also to display the finest that France could produce.[10]

Estimates of the amount spent to build Versailles are speculative. An estimate in 2000 placed the amount spent during the Ancien Régime as US$2 billion,[11] this figure being, in all probability, an under-evaluation. France's Fifth Republic expenditures alone, directed to restoration and maintenance at Versailles, undoubtedly surpass those of the Sun King.

18th century

In 1738, Louis XV remodeled the king's petit appartement on the north side of the Cour de Marbre, originally the entrance court of the old château, and built a pavilion not far from the Grand Trianon, the Petit Trianon, designed by Ange-Jacques Gabriel and completed in 1768. At the north end of the north wing, Gabriel also built a theatre, the Opéra, completed in 1770, in time for the marriage of Louis-Auguste Dauphin of France to the Austrian Archduchess Marie Antoinette. After his accession to the throne, Louis XVI made few changes to the palace, primarily to the royal private apartments.[12] However, after Louis XVI gave Marie Antoinette the Petit Trianon in 1774, the queen made extensive changes to the interior, added a theater, the Théâtre de la Reine. She also totally transformed the arboretum planted during the reign of Louis XV into what became known as the Hameau de la Reine.[13] (The trees removed from the Trianon arboretum were brought & replanted in the Jardin des Plantes in Paris.)

19th century

During the French Revolution, after the royal family's forced move to Paris on 6 October 1789 three years before the fall of the monarchy, Versailles fell into disrepair and most of the furniture was sold. Some restoration work was undertaken by Napoleon in 1810 and Louis XVIII in 1820, but the principal effort to restore and maintain Versailles was initiated by Louis-Philippe, when he created the Musée de l'Histoire de France, dedicated to "all the glories of France". The museum is located in the Aile du Midi (southern wing), which during the Ancien Régime had been used to lodge the members of the royal family. It was begun in 1833 and inaugurated on 30 June 1837. Its most famous room is the Galerie des Batailles (Hall of Battles), which lies on most of the length of the second floor.[12]

20th century

Neglect after October 1789, when the royal family had to leave Versailles, and the ravages of war in parts of the 19th and 20th centuries have left their mark on the palace and its park. Post-World War II governments have sought to repair these damages. On the whole, they have been successful, but some of the more costly items, such as the vast array of fountains, have yet to be put back completely in service. As spectacular as they might seem now, they were even more extensive in the 18th century. The 18th-century waterworks at Marly— the Machine de Marly that fed the fountains— was possibly the biggest mechanical system of its time. The water came in from afar on monumental stone aqueducts which have long ago fallen into disrepair or been torn down. Some aqueducts, such as the unfinished Canal de l'Eure, which passes through the gardens of the château de Maintenon, were never completed for want of resources or due to the exigencies of war. The search for sufficient supplies of water was never fully realised even during the apogee of the reign of the Sun King, as the fountains could not be operated together satisfactorily for any significant periods of time.[14]

The restoration initiatives launched by the Fifth Republic have proven to be perhaps more costly than the expenditures of the palace in the Ancien Régime. Starting in the 1950s, when the museum of Versailles was under the directorship of Gérald van der Kemp, the objective was to restore the palace to its state – or as close to it as possible – in 1789 when the royal family left the palace. Among the early projects was the repair of the roof over the Hall of Mirrors; the publicity campaign brought international attention to the plight of post-war Versailles and garnered much foreign money including a grant from the Rockefeller Foundation. Concurrently, in the Soviet Union (Russia since 26 December 1991), the restoration of the Pavlovsk Palace located 25 kilometers from the center of Leningrad – today's Saint Petersburg – brought the attention of French Ministry of Culture, including that of the curator of Versailles.[15]

Pavlovsk Palace was built by Catherine the Great's son Paul. The czarevitch and his wife, Marie Feodorovna, were ardent francophiles, who, on a visit to France and Versailles in May and June 1782, purchased great quantities of silk, which they later used to upholster furniture in Pavlovsk. The palace survived the Russian Revolution intact – descendants of Paul I were living in the palace at the time the communists evicted them – however, during the Second World War, the furniture and artifacts housed in the palace, which had been transformed into a museum, were removed. In the process of evacuation the museum collections, remnants of the silks purchased by Paul I of Russia and Marie Feodorovna were found and conserved. After the war when Soviet authorities were restoring the palace, which had been gutted by the retreating Nazi forces, they recreated the silk fabrics by using the conserved 18th-century remnants.[15]

When these results and high quality achieved were brought to the attention of the French Minister of Culture, he revived 18th-century weaving techniques so as to reproduce the silks used in the decoration of Versailles.[15] The two greatest achievements of this initiative are seen today in wall hangings used in the restoration of the chambre de la reine in the grand appartement de reine and the chambre du roi in the appartement du roi. While the design used for the chambre du roi was, in fact, from the original design to decorate the chambre de la reine, it nevertheless represents a great achievement in the ongoing restoration at Versailles. Additionally, this project, which took over seven years to achieve, required several hundred kilograms of silver and gold to complete.[16] One of the more costly endeavours for the museum and France's Fifth Republic has been to repurchase as much of the original furnishings as possible. However, because furniture with a royal provenance – and especially furniture that was made for Versailles – is a highly sought after commodity on the international market, the museum has spent considerable funds on retrieving much of the palace's original furnishings/[17]

21st century

The Fifth Republic has enthusiastically promoted the museum as one of France's foremost tourist attractions, with recent figures stating that nearly five million people visit the château, and 8 to 10 million walk in the gardens, every year.[18][19] In 2003, a new restoration initiative – the "Grand Versailles" project – was started, which necessitated unexpected repair and replantation of the gardens, which had lost over 10,000 trees during Hurricane Lothar on 26 December 1999. The project will be on-going for the next seventeen years, funded with a state endowment of €135 million allocated for the first seven years. It will address such concerns as security for the palace, and continued restoration of the bosquet des trois fontaines. Vinci SA underwrote the €12 million restoration project for the Hall of Mirrors, which was completed in 2006.[20]

Social history

Politics of display

On 6 May 1682, Versailles became officially the seat of the government of the kingdom of France, the home of the French king, Louis XIV, and of the location of the royal court. Symbolically, the central room of the long extensive symmetrical range of buildings was the King's Bedchamber (La Chambre du Roi), which itself was centred on the lavish and symbolic state bed, set behind a rich railing. Indeed, even the principal axis of the gardens themselves was conceived to radiate from this fulcrum. All the power of France emanated from this centre: there were government offices here; as well as the homes of thousands of courtiers, their retinues and all the attendant functionaries of court.[citation needed] By requiring that nobles of a certain rank and position spend time each year at Versailles, Louis XIV prevented them from developing their own regional power at the expense of his own, and kept them from countering his efforts to centralize the French government in an absolute monarchy. [citation needed]

At various periods before Louis XIV established absolute rule, France, like the Holy Roman Empire lacked central authority and was not the unified state it was to become during subsequent centuries.[citation needed] During the Middle Ages, French nobles were often more powerful than the King of France and, although technically loyal to him, they possessed their own provincial seats of power and government, culturally influential courts and armies loyal to them, not to the king, and the right to levy their own taxes on their subjects.[citation needed] Some families were so powerful, they achieved international prominence and contracted marriage alliances with foreign royal houses to further their own political ambitions.[citation needed] Although nominally Kings of France, de facto royal power had at times been limited purely to the region around Paris. [citation needed]

Life at Court

Life at Versailles was determined by position, favour and, above all, one's birth. The chateau was a sprawling cluster of lodgings for which courtiers vied and manipulated. Today, Versailles is seen as unparalleled in its magnificence and splendour, yet few know of the actual living conditions many of Versailles' privileged residents had to endure[citation needed]. Many modern historians have compared the palace to a vast, crowded apartment block[citation needed]. Apart from the royal family, the majority of the residents were senior members of the household.[citation needed]

On each floor apartments of varying size, 350 in all, were arranged along tiled corridors and given a number and a key. Many courtiers traded lodgings and grouped themselves together with their allies, families or friends. The Noailles family took over so much of the northern wing's attic that floor was nicknamed rue de Noailles (Noailles Street).[21]

Louis XIV envisaged Versailles as a seat for all the Bourbons, as well as his troublesome nobles. These nobles were, so to say, placed within a "gilded cage".[22] Many of the apartments were far from luxurious with many nobles having to make do with one or two room apartments, forcing many of them to build or buy town-houses in Versailles proper while keeping their palace rooms for changes of clothes or entertaining guests, rarely sleeping there.[citation needed] Rooms at Versailles were immensely useful for ambitious courtiers, as they allowed palace residents easy access to the monarch, essential to their ambitions, and gave them direct links to the latest news and gossip.[citation needed]

Political and ceremonial functions

Two of the three treaties of the Peace of Paris (1783), in which the United Kingdom recognized the independence of the United States, were signed at Versailles.

After the French defeat in the Franco-Prussian War, with the Siege of Paris dragging on, the palace was the main headquarters of the Prussian army from 5 October 1870 until 13 March 1871. On 18 January 1871, Prussian King Wilhelm I was proclaimed German Emperor in the Hall of Mirrors, and the German Empire was founded.[23]

After the First World War, it was the site of the opening of the Paris Peace Conference in 1919, also on 18 January. Germany was blamed for causing the First World War in the Treaty of Versailles, which was signed in the same room on 28 June 1919.

The palace, however, still serves political functions. Heads of state are regaled in the Hall of Mirrors; the bicameral French Parliament—consisting of the Senate (Sénat) and the National Assembly (Assemblée nationale)—meet in joint session (a congress of the French Parliament) in Versailles[24] to revise or otherwise amend the French Constitution, a tradition that came into effect with the promulgation of the 1875 Constitution.[26] For example, the Parliament met in joint session at Versailles to pass constitutional amendments in June 1999 (for domestic applicability of International Criminal Court decisions and for gender equality in candidate lists); January 2000 (ratifying the Treaty of Amsterdam), and in March 2003 (specifying the "decentralized organization" of the French Republic).[24]

In 2009, President Nicolas Sarkozy addressed the global financial crisis before a congress in Versailles, the first time that this had been done since 1848, when Charles-Louis Napoleon Bonaparte gave an address before the French Second Republic.[27][28][29]Following the November 2015 Paris attacks, President Francois Hollande gave a speech before a rare joint session of parliament at the Palace of Versailles.[30] This was the third time since 1848 that a French president addressed a joint session of the French Parliament at Versailles.[31] The president of the National Assembly has an official apartment at the Palace of Versailles.[32]

Palace and grounds

Architecture

The palace that we recognize today was largely completed by the death of Louis XIV in 1715. The eastern facing palace has a U-shaped layout, with the corps de logis and symmetrical advancing secondary wings terminating with the Dufour Pavilion on the south, and the Gabriel Pavilion to the north, creating an expansive cour d'honneur known as the Royal Court (Cour Royale). Flanking the Royal Court are two enormous asymmetrical wings that result in a facade of 1,319 feet in length.[33] Encompassing 721,182 square feet (67,000.0 m2) the palace has 700 rooms, more than 2,000 windows, 1,250 fireplaces and 67 staircases.[34]

The façade of the original lodge is preserved on the entrance front. Built of red brick and cut stone embellishments, the U-shaped layout surrounds a black-and-white marble courtyard. In the center, a 3-storey avant-corps fronted with eight red marble columns supporting a gilded wrought-iron balcony is surmounted with a triangle of lead statuary surrounding a large clock, whose hands were stopped upon the death of Louis XIV. The rest of the façade is completed with columns, painted and gilded wrought-iron balconies and dozens of stone tables decorated with consoles holding marble busts of Roman emperors. Atop the mansard slate roof are elaborate dormer windows and gilt lead roof dressings that were added by Hardouin-Mansart in 1679–1681.

Inspired by the architecture of baroque Italian villas, but executed in the French classical style, the garden front and wings were encased in white cut ashlar stone known as the enveloppe in 1661-1678. The exterior features an arcaded, rusticated ground floor, supporting a main floor with round-headed windows divided by reliefs and pilasters or columns. The attic storey has square windows and pilasters and crowned by a balustrade bearing sculptured trophies and flame pots dissimulating a flat roof.

-

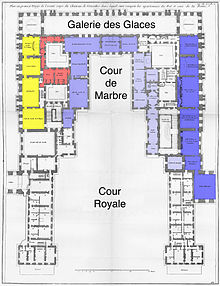

Plan of the main floor (c. 1837, with north to the right), showing the Hall of Mirrors in red, the Hall of Battles in green, the Royal Chapel in yellow, and the Royal Opera in blue

Interior

Grands appartements (State Apartments)

As a result of Le Vau's enveloppe of Louis XIII's former hunting lodge transforming it, between 1631 and 1634, into a red brick and white stone small château, with a black tile roof, the king and the queen had new apartments in the new addition, known at the time as the château neuf. The grands appartements (Grand Apartments, also referred to as the State Apartments[35]) are known respectively as the grand appartement du roi and the grand appartement de la reine. They occupied the main or principal floor of the château neuf, with three rooms in each apartment facing the garden to the west, and four facing the garden parterres to the north and south, respectively. Le Vau's design for the state apartments closely followed Italian models of the day, as evidenced by the placement of the apartments on the next floor up from the ground level—the piano nobile—a convention the architect borrowed from 16th- and 17th-century Italian palace design.[36]

The king's apartment consisted of an enfilade of seven rooms, each dedicated to one of the then known planets and their associated titular Roman deity. The queen's apartment formed a parallel enfilade with that of the grand appartement du roi. It served as the residence of three queens of France - Marie-Thérèse d'Autriche, wife of Louis XIV, Marie Leczinska, wife of Louis XV, and Marie-Antoinette, wife of Louis XVI. Additionally, Louis XIV's granddaughter-in-law, Princess Marie-Adélaïde of Savoy, duchesse de Bourgogne, wife of the Petit Dauphin, occupied these rooms from 1697 (the year of her marriage) to her death in 1712.[c] After the addition of the Hall of Mirrors (1678–1684) the king's apartment was reduced to five rooms (until the reign of Louis XV, when two more rooms were added) and the queen's to four.

Appartement du roi (King's Apartment)

The appartement du roi is a suite of rooms originally set aside for the personal use of Louis XIV in 1683. His successors, Louis XV and Louis XVI, used these rooms for such ceremonies as the lever and the coucher.

Petit appartement du roi (King's Private Apartment)

The petit appartement du roi is a suite of rooms that were reserved for the private use of the king. Occupying the site on which rooms were originally arranged for Louis XIII on the first floor of the château, the space was radically modified by Louis XIV. His successors, Louis XV and Louis XVI had these rooms drastically modified and remodeled for their personal use.

Petit appartement de la reine (Queen's Private Apartment)

The petit appartement de la reine is a suite of rooms that were reserved for the personal use of the queen. Originally arranged for the use of the Marie-Thérèse, consort of Louis XIV, the rooms were later modified for use by Marie Leszczyńska and finally for Marie-Antoinette.

Galerie des Glaces (Hall of Mirrors)

The galerie des glaces (Hall of Mirrors in English), is perhaps the most celebrated room in the château of Versailles. Setting for many of the ceremonies of the French Court during the Ancien Régime, the galerie des glaces has also inspired numerous copies and renditions throughout the world.

The room's construction began in 1678.

Chapels of Versailles

In the evolution of the palace, there have been five chapels. The current chapel, which was the last major building project of Louis XIV, represents one of the finest examples of French Baroque architecture and ecclesiastical decoration.

Royal Opera

Ange-Jacques Gabriel's Royal Opera (Opéra Royal) was perhaps the most ambitious building project of Louis XV for the château of Versailles. Completed in 1770, the Opéra was inaugurated at the time of the wedding festivities of Louis XV's grandson, the Dauphin, future Louis XVI, and Marie-Antoinette.

Museum of the History of France

In the 19th century the "Museum of the History of France" was founded in Versailles, at the behest of Louis-Philippe I, who ascended to the throne in 1830. The entire second floor (premier étage) of the aile du midi (south wing) of the palace was transformed into the Galerie des Batailles to house the newly created collection of paintings and sculptures depicting milestones battles of French history. The collections display painted, sculpted, drawn and engraved images illustrating events or personalities of the history of France since its inception. The museum occupies the lateral wings of the Palace. Most of the paintings date back to the 19th century and have been created specially for the museum by major painters of the time such as Delacroix, Horace Vernet or François Gérard but there are also much older artworks which retrace French History. Notably the museum displays works by Philippe de Champaigne, Pierre Mignard, Laurent de La Hyre, Charles Le Brun, Adam Frans van der Meulen, Nicolas de Largillière, Hyacinthe Rigaud, Jean Antoine Houdon, Jean Marc Nattier, Elisabeth Vigée Le Brun, Hubert Robert, Thomas Lawrence, Jacques-Louis David, Antoine Jean Gros and also Pierre-Auguste Renoir.

-

Queen's bedchamber in the Grand appartement de la reine

Gardens of Versailles

Evolving with the château, the gardens of Versailles represent one of the finest extant examples of the Jardin à la française created by André Le Nôtre.

Subsidiary structures

Located in proximity to the château, these smaller structures served the needs of the royal family and court officials during the Ancien Régime. They include the Ménagerie royale (1664), demolished; the Trianon de porcelaine (1670), demolished; the Grand Trianon or Trianon de marbre (Marble Trianon) (1689); the Petit Trianon (1768); and the Pavillon de la Lanterne (1787), a hunting lodge.

In popular culture

Jennifer Saunders and Dawn French starred in a 1999 BBC comedy, set within the Palace, called Let Them Eat Cake .

Singer-songwriter Al Stewart released a song entitled "The Palace of Versailles", detailing the French Revolution, The Terror, and the military coup of Napoléon Bonaparte, from the perspective of "the lonely Palace of Versailles".

On 2 July 2005, the French Live 8 was held in the courtyard of Versailles.

In 2012 animated film Madagascar 3, sophisticated chimpanzees Mason and Phil dress up as "King of Versailles" in reference to the Palace of Versailles.

The Konami video game Castlevania: Bloodlines has Versailles as the fifth stage.

The video games Assassin's Creed Unity and Assassin's Creed Rogue are set in Versailles at the beginning of Unity and the end of Rogue.

In the Doctor Who (2005) episode "Girl in the Fire Place", The Doctor met the Madame de Pompadour in the Palace of Versailles.

Gallery

-

Panoramic view from the park

-

Panoramic view from the city

-

Garden facade from the southwest

-

Salle du Sacre with a view toward Salle des Gardes in the Queen's Grand Apartment

-

View of the upper southwest corner of the south wing

-

View of the Palace from the southern part of the Parterre d'Eau, with the bronze statue of the Rhône River by Jean-Baptiste Tuby (1687)

-

Marble Court

See also

- Bureau du Roi

- Châteaux of the Loire Valley

- List of Baroque residences

- Paris Peace Conference, 1919

- Peterhof Palace

- Tennis Court Oath (Template:Lang-fr) in the Saint-Louis district

- Treaty of Versailles

- Versailles Cathedral

Notes

- ^ The marc, a unit equal to 8 ounces, was used to weigh silver and gold.

- ^ As of 4 April 2008, silver has been trading in New York at US$17.83 an ounce.

- ^ Six kings were born in this room: Philip V of Spain, Louis XV, Louis XVI, Louis XVII, Louis XVIII, and Charles X.

References

Footnotes

- ^ Ayers 2004, pp. 334–336.

- ^ Berger 1985a, pp. 17–19.

- ^ Ayers 2004, pp. 336–339; Maral 2010, pp. 215–229.

- ^ La Varende 1959[page needed]

- ^ Bluche 1986[page needed]; Bluche 1991[page needed]; Chouquette 1997[page needed]

- ^ a b Guiffrey 1880–1890[page needed]

- ^ a b c d Bluche 1991[page needed]

- ^ Buckland 1983[page needed]

- ^ Dangeau 1854–1860[page needed]

- ^ Bluche 1986[page needed]; Bluche 1991[page needed]

- ^ Littell 2000[page needed]

- ^ a b Hoog 1996.

- ^ Hoog 1996, pp. 373–374.

- ^ The magic of the “Great Waters” of Versailles

- ^ a b c Massie 1990[page needed]

- ^ Meyer 1989[page needed]

- ^ Kemp 1976[page needed]

- ^ At the Court of the Sun King, Some All-American Art, New York Times (September 11, 2008).

- ^ Opperman 2004[page needed]

- ^ Leloup 2006[page needed]

- ^ Da Vinha, Mathieu & Masson, Raphaël: Versailles: Histoire, Dictionnaire & Anthologie - Chapter: Aile du Nord, Publisher: Robert Laffont, Paris, 10 September 2015, [1](no page number available). ISBN 978-2221115022

- ^ Duc de Saint-Simon[page needed]

- ^ Wawro 2003, p. 282

- ^ a b William Safran, "France" in Politics in Europe (M. Donald Hancock et al., CQ Sage: 5th ed. 2012).

- ^ |Constitution of 1875

- ^ Article 9: Le siège du pouvoir exécutif et des deux chambres est à Versailles.[25]

- ^ Associated Press, Breaking tradition, Sarkozy speaks to parliament (June 22, 2009).

- ^ Jerry M. Rosenberg, "France" in The Concise Encyclopedia of The Great Recession 2007-2012 (Scarecrow Press: 2012), p. 262.

- ^ Associated Press, The Latest: US Basketball Player James Not Going to France (November 16, 2015).

- ^ Associated Press, The Latest: Brother Linked to Paris Attacks in Disbelief (November 16, 2015).

- ^ Francois Hollande: 'France is at war', CNN (November 16, 2015).

- ^ Georges Bergougnous, Presiding Officers of National Parliamentary Assemblies: A World Comparative Study (Inter-Parliamentary Union: Geneva, 1997), p. 39.

- ^ "History of Art". Visual Arts Cork. Retrieved 10 August 2016.

- ^ "Palace of Versailles". Dimensions Info. Retrieved 10 August 2016.

- ^ Saule & Meyrer 2000, pp. 18, 22; Michelin Tyre 1989, p. 182.

- ^ Berger 1985b[page needed]; Verlet 1985[page needed]

- ^ Blondel 1752–1756, vol. 4 (1756), book 7, plate 8; Nolhac 1898, p. 49 (dates Blondel's plan to c. 1742).

Works cited

- Ayers, Andrew (2004). The Architecture of Paris. Stuttgart, London: Edition Axel Menges. ISBN 9783930698967.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Berger, Robert W. (1985a). In the Garden of the Sun King: Studies on the Park of Versailles Under Louis XIV. Washington, DC: Dumbarton Oaks Research Library.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Berger, Robert W. (1985b). Versailles: The Château of Louis XIV. University Park: The College Arts Association.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Blondel, Jacque-François (1752–1756). Architecture françoise, ou Recueil des plans, élévations, coupes et profils des églises, maisons royales, palais, hôtels & édifices les plus considérables de Paris. Vol. 4 vols. Paris: Charles-Antoine Jombert.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Bluche, François (1986). Louis XIV. Paris: Arthème Fayard.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Bluche, François (1991). Dictionnaire du Grand Siècle. Paris: Arthème Fayard.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Buckland, Frances (May 1983). "Gobelin tapestries and paintings as a source of information about the silver furniture of Louis XIV". The Burlington Magazine. 125 (962): 272–283.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Dangeau, Philippe de Courcillon, marquis de (1854–60). Journal. Paris.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Gady, Alexandre (2010). "Édifices royaux, Versailles: Transformations des logis sur cour". In Gady, Alexandre (ed.). Jules hardouin-Mansart 1646–1708. Paris: Éditions de la Maison des sciences de l'homme. pp. 171–176. ISBN 9782735111879.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Guiffrey, Jules (1880–1890). Comptes des bâtiments du roi sous le règne de Louis XIV. Vol. 5 vols. Paris: Imprimerie Nationale.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Hoog, Simone (1996). "Versailles". In Turner, Jane (ed.). The Dictionary of Art. Vol. 32. New York: Grove. pp. 369–374. ISBN 9781884446009.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) Also at Oxford Art Online (subscription required). - Kemp, Gerard van der (1976). "Remeubler Versailles". Revue du Louvre. 3: 135–137.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - La Varende, Jean de (1959). Versailles. Paris: Henri Lefebvre.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Leloup, Michèle (7 August 2006). "Versailles en grande toilette". L'Express.

{{cite news}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Littell, McDougal (2001). World History: Patterns of Interactions. New York: Houghton Mifflin.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Maral, Alexandre (2010). "Chapelle royale". In Gady, Alexandre (ed.). Jules hardouin-Mansart 1646–1708. Paris: Éditions de la Maison des sciences de l'homme. pp. 215––228. ISBN 9782735111879.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Massie, Suzanne (1990). Pavlosk: The Life of a Russian Palace. Boston: Little, Brown, and Company.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Meyer, Daniel (February 1989). "L'ameublement de la chambre de Louis XIV à Versailles de 1701 à nos jours". Gazette des Beaux-Arts. 113 (6th ed.): 79–104.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help); Unknown parameter|authormask=ignored (|author-mask=suggested) (help) - Michelin Tyre PLC (1989). Île-de-France: The Region Around Paris. Harrow [England]: Michelin Tyre Public Ltd. Co. ISBN 9782060134116.

- Nolhac, Pierre de (1898). La création de Versailles sous Louis Quinze. Paris: H. Champion.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Oppermann, Fabien (2004). Images et usages du château de Versailles au XXe siècle (Thesis). École des Chartes.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Saule, Béatrix; Meyer, Daniel (2000). Versailles Visitor's Guide. Versailles: Éditions Art-Lys. ISBN 9782854951172.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Verlet, Pierre (1985). Le château de Versailles. Paris: Librairie Arthème Fayard.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Wawro, Geoffrey (2003). The Franco-Prussian War: the German conquest of France in 1870–1871. Cambridge University Press.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)

External links

- Palace of Versailles

- Art museums and galleries in France

- Baroque architecture at Versailles

- Baroque palaces

- Buildings and structures completed in 1672

- Buildings and structures completed in 1684

- Châteaux in France

- French formal gardens

- Gardens in Yvelines

- Landscape design history of France

- Palaces in France

- French Parliament

- Reportedly haunted locations in France

- Royal residences in France

- Seats of national legislatures

- World Heritage Sites in France

- Châteaux in Yvelines

- Visitor attractions in Yvelines

- Museums in Yvelines

- 1684 establishments in France