Energy in Iceland

About 85 percent of total primary energy supply in Iceland is derived from domestically produced renewable energy sources.[1]

In 2011, geothermal energy provided about 65 percent of primary energy, the share of hydropower was 20 percent, and the share of fossil fuels (mainly oil products for the transport sector) was 15 percent.[1] In 2013, Iceland also became a producer of wind energy.[2]

The main use of geothermal energy is for space heating with the heat being distributed to buildings through extensive district-heating systems.[1] About 85% of all houses in Iceland are heated with geothermal energy.[3]

Renewable energy provides almost 100 percent of electricity production, with about 75 percent coming from hydropower and 25 percent from geothermal power.[1] Most of the hydropower plants are owned by Landsvirkjun (the National Power Company) which is the main supplier of electricity in Iceland.[3] In 2011, the total electricity consumption in Iceland was 17,210 GWh.[4]

Iceland is the world’s largest green energy producer per capita and largest electricity producer per capita.[5]

Geology

Iceland's unique geology allows it to produce renewable energy relatively cheaply, from a variety of sources. Iceland is located on the Mid-Atlantic Ridge, which makes it one of the most tectonically active places in the world. There are over 200 volcanoes located in Iceland and over 600 hot springs.[6] There are over 20 high-temperature steam fields that are at least 150 °C [300 °F]; many of them reach temperatures of 250 °C.[6] This is what allows Iceland to harness geothermal energy and these steam fields are used for everything from heating houses to heating swimming pools. Hydropower is harnessed through glacial rivers and waterfalls, which are both plentiful in Iceland.[6]

Hydropower

The first hydropower plant was built in 1904 by a local entrepreneur.[7] It was located in a small town outside of Reykjavík and produced 9 kW of power. The first municipal hydroelectric plant was built in 1921, and it could produce 1 MW of power. This plant single-handedly quadrupled the amount of electricity in the country.[8] The 1950s marked the next evolution in hydroelectric plants. Two plants were built on the Sog River, one in 1953 which produced 31 MW, and the other in 1959 which produced 26.4 MW. These two plants were the first built for industrial purposes and they were co-owned by the Icelandic government.[8] This process continued in 1965 when the national power company, Landsvirkjun, was founded. It was owned by both the Icelandic government and the municipality of Reykjavík. In 1969, they built a 210 MW plant on the Þjórsá River that would supply the southeastern area of Iceland with electricity and run an aluminum smelting plant that could produce 33,000 tons of aluminum a year.[8]

This trend continued and increases in the production of hydroelectric power are directly related to industrial development. In 2005, Landsvirkjun produced 7,143 GWh of electricity total of which 6,676 GWh or 93% was produced via hydroelectric power plants. Additionally 5,193 GWh or 72% was used for power-intensive industries like aluminum smelting.[9] In 2009 Iceland built its biggest hydroelectric project to date, a 690 MW hydroelectric plant to provide energy for another aluminum smelter —[10] the Kárahnjúkar Hydropower Plant. This project was opposed strongly by environmentalists.

Other hydroelectric power stations in Iceland include: Blöndustöð (150 MW), Búrfellsstöð (270 MW), Hrauneyjafosstöð (210 MW), Laxárstöðvar (28 MW), Sigöldustöð (150 MW), Sogsstöðvar (89 MW), Sultartangastöð (120 MW), and Vatnsfellsstöð (90 MW).[11]

Iceland is the first country in the world to create an economy generated through industries fueled by renewable energy, and there is still a large amount of untapped hydroelectric energy in Iceland. In 2002 it was estimated that Iceland only generated 17% of the total harnessable hydroelectric energy in the country. Iceland’s government believes another 30 TWh of hydropower every year could be produced, whilst taking into account the sources that must remain untapped for environmental reasons.[10]

Geothermal power

For centuries, the people of Iceland have used their hot springs for bathing and washing clothes. The first use of geothermal energy for heating did not come until 1907 when a farmer ran a concrete pipe from a hot spring that led steam into his house.[12] In 1930, the first pipeline was constructed in Reykjavík, and was used to heat two schools, 60 homes, and the main hospital. It was a 3 km pipeline that ran from one of the hot springs outside the city. In 1943, the first district heating company was started with the use of geothermal power. An 18 km pipeline ran through the city of Reykjavík and by 1945 it was connected to over 2,850 homes.[6]

Currently geothermal power heats 89%[6] of the houses in Iceland and over 54% of the primary energy used in Iceland comes from geothermal sources. Geothermal power is used for many things in Iceland. 57.4% of the energy is used for space heat, 25% is used for electricity, and the remaining amount is used in many miscellaneous areas: swimming pools, fish farms, and greenhouses, for example.[6]

The government of Iceland has played a major role in the advancement of geothermal energy. In the 1940s, the State Electricity Authority was started by the government in order to increase the knowledge of geothermal resources and the utilization of geothermal power in Iceland. It was later changed to the National Energy Authority (Orkustofnun) in 1967. This agency has been very successful and has made it economically viable to use geothermal energy as a source for heating in many different areas throughout the country. Geothermal power has been so successful that the government no longer has to lead the research in this field because it has been taken over by the geothermal industries.[6]

Geothermal power plants in Iceland include Nesjavellir (120 MW), Reykjanes (100 MW), Hellisheiði (303 MW), Krafla (60 MW), and Svartsengi (46.5 MW) power plants.[13] The Svartsengi power plant and the Nesjavellir power plant produce both electricity and hot-water for heating purposes. The move from oil-based heating to geothermal heating saved Iceland an estimated total of US $8.2 billion from 1970 to 2000 and lowered the release of carbon dioxide emissions by 37%.[6] The equivalent amount of oil that would have been needed in 2003 to heat Iceland’s homes was 646,000 tons.

The Icelandic government also believes that there are many more untapped geothermal sources throughout the country, estimating that over 20 TWh per year of unharnessed geothermal energy is available. This is about 3.3% of the 600TWh per year of electricity used in Germany. Combined with the unharnessed feasible hydropower, tapping these sources to their full extent would provide Iceland another 50 TWh of energy per year, all from renewable sources.[10]

Iceland's abundant geothermal energy has also enabled renewable energy initiatives, such as Carbon Recycling International's carbon dioxide to methanol fuel process, which could help reduce Iceland's dependence on fossil fuels.[14]

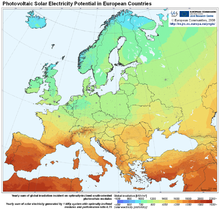

Solar power

Source: NREL[15] |

|

Iceland has relatively low insolation, due to the latitude, about 20% less than Paris, and half as much as Madrid, with very little in the winter. Unlike geothermal, solar power is a non-dispatchable renewable energy source - the sun follows a predictable path but the weather is not controllable. This makes both wind power and solar power variable renewable energy (VRE) sources. Net metering credits electricity generated during the summer for use during the winter. If net metering nor local energy storage is not available, the largest array that is practical for a consumer to install is that which will generate less than or equal to the amount of electricity used during the sunniest month, a much smaller array.[16]

Hydrogen

Currently, imported oil fulfils most of Iceland's remaining energy needs. This cost has caused Iceland to focus on domestic, renewable energy. Bragi Arnason, a local professor, first proposed the idea of using hydrogen as a fuel source in Iceland during the 1970s, which is also when the oil crisis occurred. At that point in time this idea was considered untenable, but in 1999 Icelandic New Energy was established to govern the project of transitioning Iceland into the first hydrogen society by 2050.[17] This followed a decision in 1998 by the Icelandic Parliament to convert vehicle and fishing fleets to hydrogen produced from renewable energy.[18]

Iceland provides an ideal location to test the viability of hydrogen as a fuel source for the future, since it is a small country of only 320,000 people, with over 60% living in the capital, Reykjavík. The relatively small scale of the infrastructure will make it easier to transition the country from oil to hydrogen. There is also a plentiful supply of natural energy that can be harnessed to produce hydrogen in a renewable way, making it perfect for hydrogen production. Iceland is a participant in international hydrogen fuel research and development programs, and many countries are following the nation's progress with interest. However, these factors also make Iceland an advantageous market for electric vehicles. Because electric vehicles are four times more efficient, and less expensive than hydrogen vehicles, the country may switch to electric vehicles.[19]

Iceland already converts its surplus electricity into exportable goods and hydrocarbon replacements. In 2002 it produced 2,000 tons of hydrogen gas by electrolysis—primarily for the production of ammonia for fertilizer.

ECTOS demonstration project

The first step towards becoming a hydrogen society was the ECTOS demonstration project, which ran from 2001 until August 2005 and was very successful.[20] ECTOS (Ecological City TranspOrt System) involved three hydrogen fuel cell buses and one fuel station.[21] Many international companies contributed to the project including Daimler Chrysler, who made the hydrogen fuel cell buses, and Shell which produced the hydrogen fuel station.[22] The European Commission 5th framework programme sponsored the project.

The first hydrogen fuel station in Iceland opened in 2003 in Reykjavík.[23] To avoid transportation difficulties hydrogen is produced on site using electrolysis to break down water into hydrogen and oxygen. All of the energy used to produce the hydrogen comes from Iceland’s renewable energies and the full cycle of energy, from the water to the hydrogen in the fuel cells, emits no CO2.[17]

During the project the researchers studied the efficiency of using hydrogen as a fuel source. They examined the reliability of the fuel and effectiveness of hydrogen as a fuel in buses. They also studied the cost effectiveness of using hydrogen as a fuel source and how the process of introducing hydrogen into the country could be implemented. They examined specific areas like the ease of incorporating fuel stations and producing hydrogen, and the safety precautions involved with distributing and using hydrogen, a very explosive fuel.

HyFLEET:CUTE project

In January 2006 it was decided to continue testing the hydrogen buses as part of the HyFLEET:CUTE project, which spans 10 cities in Europe, China and Australia and which is sponsored by the European Commission's 6th framework programme.[24] This project studies the long term effects and most efficient ways of using hydrogen powered buses. The buses are run for longer periods of time and the durability of the fuel cell is compared to the combustion engine, which can theoretically last a lot longer. The project also compares the fuel efficiency of the original buses with new buses from different manufacturers that are supposed to be more fuel efficient.[17]

The project ended in January 2007, and as a result of the research an improved bus prototype is expected in 2008. Details of further demonstrations involving private cars and a boat were expected in April 2007.[25]

Other projects

Iceland has also begun many other projects involving hydrogen.

The EURO-HYPORT project is investigating the feasibility of exporting hydrogen fuel to Europe. Options include transporting the gas through an undersea pipeline or by boat, or exporting electricity generated in Iceland through a submarine cable.[17]

Another project to build a hydrogen-powered H-ship started in February 2004 and is looking at the practicalities of using hydrogen as a fuel for Iceland's fishing fleet, one of the country's main industries. The project will identify and try to remove barriers that may prevent marine vehicles from using hydrogen as a fuel, such as problems caused by water and salt. It will also try to identify and remedy weakness within the fuel cell to ensure the protection of marine life. The H-ship project is a major step in the plan for Iceland to become the first country to phase out the use of fossil fuels. Government funding as well as private organizations such as the World Renewable Energy Congress are the primary sponsors of research in this sector.[17]

From hydrogen to electricity

Electric cars with strategically located charging stations make a lot of sense for Iceland, where 75 percent of the country’s residents live within 37 miles of the capital city. Hydrogen cars are not expected to be mass-produced anywhere in the world until at least 2015, and with the first electric cars rolling off production lines in 2010, it will be faster to introduce electric vehicles.[19] Iceland's 840-mile-long ring road could theoretically be covered with just 14 fast-charging stations.[26]

Education and research

There are several educational institutions that offering education in Renewable Energy in Iceland on university level.

The University of Iceland is a progressive educational and scientific institution, renowned in the global scientific community for its research. It is a state university, situated in Reykjavík, the capital of Iceland. A modern, diversified and rapidly developing institution, the University of Iceland offers opportunities for study and research in almost 300 programmes spanning most fields of science and scholarship: Social Sciences, Health Sciences, Humanities, Sciences and Engineering. Some 9700 students are registered at UI and 1000 full-time employees.

Reykjavik University has the mission to create and communicate knowledge, in order to increase the competitiveness of individuals, firms and society as a whole, while at the same time enhancing the quality of life of their students and staff. The aim is to make Reykjavik University the centre for international research collaborations in Europe and across the Atlantic. The university consists of five academic schools: School of Law, School of Business, School of Health and Education, School of Computer Science and the School of Science and Engineering. Reykjavik University is a community of over 3000 students and over 500 full-time and part-time employees. About half of all instructors at RU are active in Icelandic industry, and about 10% are guest instructors from overseas.

Keilir, Atlantic center of excellence in Ásbrú next to the Keflavik International Airport, offer a multidisciplinary BSc. programs in energy technology in co-operation with the University of Iceland. The school also runs a state-of-the-art research center in energy sciences.

RES - The School for Renewable Energy Science, located in Akureyri North Iceland is offering an intensive and unique interdisciplinary research oriented one-year graduate (M.Sc.) programme in Renewable Energy Science. The program is offered in cooperation with University of Iceland and University of Akureyri, as well as in partnership with a number of leading technical universities around the world. In 2009 the school offers four specializations of study: 1. Geothermal Energy; 2. Fuel Cell Systems and Hydrogen; 3. Biofuels and Bioenergy; and 4. Energy Systems & Policies. RES offers also summer programs and individual courses in the field.

REYST located in Reykjavik, is also offering MSc. Studies in the field of renewable Energy. The foundation for Reykjavik Energy Graduate School of Sustainable Systems was laid in April 2007 when Reykjavik Energy, the University of Iceland and Reykjavik University signed an agreement on establishing an international graduate programme on sustainable energy.

RESYT is an interdisciplinary school in higher education for engineers and scientists, has a focus on global environmental protection and sustainable use of energy resources and creates leading experts in management, design and research in utilization of sustainable energy. The unique expertise of all its founding partners forms an excellent platform for the school to build on.

The largest research institution in renewable energy in the country is University of Iceland which is state university, founded in 1911 and situated in the heart of Reykjavík, the capital of Iceland. As a scientific institution is it renowned in the global scientific community for its research in renewable energy.

Another state university University of Akureyri, located in Akureyri in North Iceland, is also conducting various research in the field of renewable energy.

One of the main tasks of the National Energy Authority of Iceland is to carry out energy research and provide consulting services related to energy development and energy utilization.

Several companies, public and private are conducting extensive research in the field of renewable energy.

Landsvirkjun the national electricity company of the Republic of Iceland, is both in research of hydro and geothermal as well and funding a great deal of research work in the field in the country.

The Icelandic Energy Portal is an independent information source on the Icelandic energy sector.

Iceland Geosurvey (ÍSOR) is a public consulting and research institute providing specialist services to the Icelandic power industry, dedicated mainly to geothermal and hydro research.

See also

- Electricity sector in Iceland

- Economy of Iceland

- Icelandic New Energy

- Reykjavik Geothermal

- Dreamland: A Self-Help Manual for a Frightened Nation

References

- ^ a b c d Icelandic Energy Portal

- ^ Iceland Energy Portal News [1]

- ^ a b Energy in Iceland

- ^ Iceland Energy Portal News [2]

- ^ Iceland Energy Portal News [3]

- ^ a b c d e f g h Sveinbjorn Bjornsson, Geothermal Development and Research in Iceland (Ed. Helga Bardadottir. Reykjavik: Gudjon O, 2006) Cite error: The named reference "Bjornsson" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ Icelandic Energy Portal [4]

- ^ a b c 19th World Energy Congress, Sustainable Generation and Utilization of Energy The Case of Iceland (Sydney: 2004)

- ^ Electricity Production, Landsvirkjun, accessed 2007-04-19)

- ^ a b c Helga Bardadottir, Energy in Iceland. (Reykjavik: Hja Godjon O, 2004)

- ^ Icelandic Energy Portal [5]

- ^ Icelandic Energy Portal [6]

- ^ Icelandic Energy Portal [7]

- ^ "Technology". Carbon Recycling International. 2011. Retrieved 11 July 2012.

- ^ "PV Watts". NREL. Retrieved 2012-04-16.

- ^ The Grid Impacts of Net Metering

- ^ a b c d e Icelandic New Energy, accessed 2007-05-02

- ^ Powering The Plains, South Dakota Public Utilities Commission, published 2003, accessed 2007-05-14

- ^ a b Motavalli, Jim. "Iceland: Here we are, plug us in". Mother Nature Network, August 11, 2010

- ^ ECTOS - hydrogen buses in Reykjavik Iceland, SU:GRE, published 2007, accessed 2007-05-04

- ^ ECTOS web site accessed 2007-05-14

- ^ Iceland's hydrogen buses zip toward oil-free economy, The Detroit News via Reuters, published 2005-01-14, accessed 2007-05-14

- ^ Hydrogen-filling station opens ... in Iceland, USA Today, published 2003-04-25, accessed 2007-05-21

- ^ HyFLEET:CUTE official web site

- ^ Successful ending of HyFleet:Cute and ECTOS, Icelandic New Energy, published 2007-03-2007, accessed 2007-05-14

- ^ http://www.calcars.org/calcars-news/1006.html

Bibliography

- 19th World Energy Congress. Sustainable Generation and Utilization of Energy The Case of Iceland. Sydney: 2004.

- Bardadottir, Helga. Energy in Iceland. Reykjavik: Hja Godjon O, 2004.

- Bjornsson, Sveinbjorn. Geothermal Development and Research in Iceland. Ed. Helga Bardadottir. Reykjavik: Gudjon O, 2006.

External links

- Icelandic Energy Portal

- Renewable Energy in Iceland - Nordic Energy Solutions

- Kárahnjúkar hydropower project

- Saving Iceland - direct action movement against heavy industry, large dams and large-scale geothermal exploitation in Iceland

- Orkustofnun - Icelandic National Energy Authority

- Hydrogen in Iceland: Current status and future aspects (Icelandic New Energy, September 2006)

- Energy in Iceland: The Resource, its Utilisation and the Energy Policy (Minister of Industry and Commerce, 2000-01-03)

- Iceland President Grímsson: wind power, clean energy on YouTube - a short talk by Ólafur Ragnar Grímsson

- Geothermal Energy Leaves the Window Open for Iceland's Economy

- "Meet Iceland - a Pioneer in the Use of Renewable Resources". A brochure on renewable energy solutions in Iceland. Touches upon everything from geothoermal and hydro, to alternative fuels.