Stripped Classicism

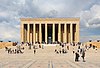

Stripped Classicism (or "Starved Classicism" or "Grecian Moderne")[1] is primarily a 20th-century classicist architectural style stripped of most or all ornamentation, frequently employed by governments while designing official buildings. It was adapted by both totalitarian and democratic regimes.[A] The style embraces a "simplified but recognizable" classicism in its overall massing and scale while eliminating traditional decorative detailing.[3][4][5][6] The orders of architecture are only hinted at or are indirectly implicated in the form and structure.[B]

Despite its etymological similarity, Stripped Classicism is sometimes distinguished from "Starved Classicism", the latter "displaying little feeling for rules, proportions, details, and finesse, and lacking all verve and élan".[5][7] At other times the terms "stripped" and "starved" are used interchangeably.[8][9]

Description and history

Though the term is usually reserved for the more thorough style that forms part of 20th-century rational architecture,[5] characteristics of Stripped Classicism are embodied in works of some progressive late 18th- and early 19th-century neoclassical architects, such as Étienne-Louis Boullée, Claude Nicolas Ledoux, Friedrich Gilly, Peter Speeth, Sir John Soane and Karl Friedrich Schinkel.[5]

Between the World Wars, a stripped-down classicism became the de facto standard for many monumental and institutional governmental buildings all over the world.[2] Governments used this architectural méthode to straddle modernism and classicism, an ideal political response to a modernizing world.[10] In part, this movement was said to have origins in the need to save money in governmental works by eschewing the expense of hand-worked classical detail.[6]

In Europe, examples as early as the German embassy in Russia, designed by Peter Behrens and completed in 1912, "established models for the classical purity aspired to by high modernists like Mies van der Rohe but also for the oversized, Stripped Classicism of Hitler's, Stalin's and Ulbricht's architects and perhaps of American, British and French official buildings in the 1930s as well".[11] The style later found adherents in the Fascist regimes of Germany[12] and Italy as well as in the Soviet Union during Stalin's regime.[13] Albert Speer's Zeppelinfeld and other parts of the Nazi party rally grounds complex outside Nuremberg was perhaps the most famous example in Germany, using classical elements such as columns and altars alongside modern technology such as spotlights. The Casa del Fascio in Como has also been aligned with the movement. In the USSR some of the proposals for the unbuilt Palace of the Soviets also had characteristics of the style.[2]

Among American architects, the work of Paul Philippe Cret exemplifies the style. His Château-Thierry American Monument built in 1928 has been identified as an early example.[14] Among his other works identified with the style are the exterior of the 1933 Folger Shakespeare Library in Washington, D.C. (though not the Tudor Revival library interior), the 1937 University of Texas at Austin's Main Tower, the 1937 Federal Reserve Building in Washington, D.C. and the 1939 Bethesda Naval Hospital tower.[14][15][16]

It is sometimes evident in buildings that were constructed by the Works Projects Administration during the Great Depression, albeit with a mix of Art Deco architecture or its elements. Related styles have been described as PWA Moderne and Greco Deco.[17][18]

The movement was widespread, and transcended national boundaries. Architects who at least notably experimented in Stripped Classicism included John James Burnet, Giorgio Grassi, Léon Krier, Aldo Rossi, Albert Speer, Robert A. M. Stern and Paul Troost.[C][5]

Despite its popularity with totalitarian regimes, it has been adapted by many English-speaking democratic governments, including during the New Deal in the United States.[2] In any event, presumed "fascist" underpinnings have hampered acceptance into mainstream architectural thought.[2] There is no evidence that architects who favored this style had a particular right-wing political disposition. Nevertheless, both Adolf Hitler and Benito Mussolini were fans.[19][20] On the other hand, Stripped Classicism was favored by Joseph Stalin and various regional Communist regimes.[13]

After the fall of the Third Reich and end of World War II, the style fell out of favor. However, it was somewhat revived in designs in the 1960s.[6] Included was Philip Johnson's New York Lincoln Center for the Performing Arts,[6] evidencing "a revival in the Stripped Classical style". Likewise, Canberra, Australia saw the Law Courts of the ACT (1961) and the National Library of Australia (1968) resurrect grand Stripped Classical designs.[6][21] See Australian non-residential architectural styles.

Notable examples

See also

- Boris Iofan

- Constructivist architecture

- Dulwich Picture Gallery and Mausoleum[5]

- Futurist architecture

- Giuseppe Terragni

- Nazi architecture

- Stalinist architecture

Notes

- ^ "Stripped Classicism was a widely popular, international style of architecture during the inter-war period. It is best defined as a pared down version of classicism that blended the classical vocabulary with the ever-growing desire for abstraction... Due to its strong associations with totalitarian governments, it is often excluded from the canonic historical narrative of the modern movement. Recently a growing number of scholars have begun to question the traditional definition of modern architecture. If the discussion on modernism is expanding beyond the traditional canonical definition, a greater understanding of Stripped Classicism’s place amongst the modern movement can be achieved."[2]

- ^ Thus, for example, cuts might be substituted for moldings.[5]

- ^ German architect and husband of architect Gerdy Troost[5]

Citations

- ^ a b Willingham, William F. (Spring 2013). "Architecture of the Oregon State Capitol". Oregon Historical Quarterly. 114 (1). Oregon Historical Society: 94–107. Retrieved December 6, 2014. Jstor (subscription required)

- ^ a b c d e Bryant 2011.

- ^ Sennott, Stephen, Editor (2004). Encyclopedia of Twentieth Century Architecture. New York: Fitzroy Dearborn. p. 269. ISBN 1579582435. ISBN 978-1579582432.

{{cite encyclopedia}}:|first1=has generic name (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "Stripped Classical 1900-1945". Essential Architecture. Retrieved December 5, 2014.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Curl, James Stevens (2000). "Stripped Classicism". A Dictionary of Architecture and Landscape Architecture. Encyclopedia.com. Retrieved December 6, 2014.

- ^ a b c d e "Post War Stripped Classical". Archipaedia-archive. Archipaedia world architecture. November 23, 2009. Retrieved December 6, 2014.

- ^ Cf, Curl, James Stevens (2000). "Starved Classicism". A Dictionary of Architecture and Landscape Architecture. Encyclopedia.com. Retrieved December 6, 2014.

- ^ http://articles.chicagotribune.com/1985-06-09/entertainment/8502060257_1_adolf-hitler-classical-architecture-postmodern-buildings/3

- ^ https://suzassippi.wordpress.com/2015/10/04/frist-center-for-the-arts-former-us-post-office-in-nashville/

- ^ Bryant 2011, p. 5.

- ^ Ladd, Brian (June 27, 2004). The Companion Guide to Berlin. Woodbridge Rochester, NY: Companion Guides. p. 205. ISBN 1900639289. ISBN 978-1900639286. Retrieved December 5, 2014.

- ^ "Fascist Stripped Classical (German)". Essential Architecture. Retrieved December 5, 2014.

- ^ a b tjaaf (November 24, 2009). "Stalinist Architecture- Regional varieties". Archipaedia-archive. Archipaedia world architecture. Retrieved December 6, 2014.

- ^ a b Rybczynski, Witold. "The Late, Great Paul Cret". The New York Times Style Magazine Blogs. Retrieved 5 December 2014.

- ^ Moeller Jr., G. Martin (May 2, 2012). AIA Guide to the Architecture of Washington (Fifth ed.). Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 978-1421402703. ISBN 142140270X.

- ^ Applewhite, E. J. (1993). Washington Itself: An Informal Guide to the Capital of the United States. Lanham, Md: Madison Books. p. 165. ISBN 1568330081. ISBN 9781568330082.

- ^ Prosser, Daniel (1992). The New Deal Builds: Government Architecture during the New Deal. Vol. 9. pp. 40–54.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ^ Greif, Martin (1975). Depression Modern: The Thirties Style in America. New York: Universe Books.

- ^ "Stripped Classical". Archipaedia-archive. Archipaedia world architecture. November 23, 2009. Retrieved December 6, 2014.

- ^ "Fascist Stripped Classical (German)". Archipaedia-archiv. Archipaedia world architecture. November 24, 2009. Retrieved December 6, 2014.

- ^ "Late twentieth century Stripped Classical". Retrieved December 6, 2014.

- ^ Goley, Mary Anne – Director, Fine Arts Program of the Federal Reserve Board. "Architecture of the Eccles Building". Federal Reserve Board. Archived from the original on June 12, 2002. Retrieved December 6, 2014.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) at Internet archive/Wayback machine - ^ "Front Matter". Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory: J-PART. 11 (2). Oxford University Press on behalf of the Public Management Research Association: i-264. April 2001. doi:10.2307/3525687. JSTOR 3525687.

- ^ Irving, Robert; Powell, Ron; Irving, Noel (2014). Sydney' hard rock story: the cultural heritage of trachyte. Leura, N.S.W.: Heritage Publishing. p. 137. ISBN 9781875891160.

Sources

- Bryant, Brittany Paige (June 2011). "Reassessing Stripped Classicism within the Narrative of International Modernism in the 1920s-1930s" (PDF). Thesis — Savannah College of Art and Design. Retrieved 5 December 2014.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)