Summer of Love

The Summer of Love was a social phenomenon that occurred during the summer of 1967, when as many as 100,000 people converged in the Haight-Ashbury neighborhood of San Francisco. Although hippies also gathered in major cities across the U.S., Canada and Europe, San Francisco remained the center of the hippie movement.[1] Like its sister enclave of Greenwich Village, the city became even more of a melting pot of politics, music, drugs, creativity, and the total lack of sexual and social inhibition than it already was. As the hippie counterculture movement came further forward into public awareness, the activities centered therein became a defining moment of the 1960s,[2] causing numerous 'ordinary citizens' to begin questioning everything and anything about them and their environment as a result.

This unprecedented gathering of young people is often considered to have been a social experiment, because of all the alternative lifestyles which became more common and accepted such as gender equality, communal living, and free love.[3] Many of these types of social changes reverberated on into the early 1970s, and effects echo throughout modern society.

The hippies, sometimes called flower children, were an eclectic group. Many were suspicious of the government, rejected consumerist values, and generally opposed the Vietnam War. A few were interested in politics; others focused on art (music, painting, poetry in particular) or religious and meditative movements. All were eager to integrate new ideas and insights into daily life, both public and private.[4]

Early 1967

Inspired by the Beats of the 1950s, who had flourished in the North Beach area of San Francisco, those who gathered in Haight-Ashbury in 1967 rejected the conformist values of Cold War America. These hippies rejected the material values of modern life; there was an emphasis on sharing and community. The Diggers established a Free Store, and a Free Clinic for medical treatment was started.[5]

The prelude to the Summer of Love was the Human Be-In at Golden Gate Park on January 14, 1967, which was produced and organized by artist Michael Bowen[6][7] as a "gathering of tribes".[8]

James Rado and Gerome Ragni were in attendance and absorbed the whole experience; this became the basis for the musical Hair. Rado recalled, "There was so much excitement in the streets and the parks and the hippie areas, and we thought `If we could transmit this excitement to the stage it would be wonderful....' We hung out with them and went to their Be-Ins [and] let our hair grow. It was very important historically, and if we hadn't written it, there'd not be any examples. You could read about it and see film clips, but you'd never experience it. We thought, 'This is happening in the streets,' and we wanted to bring it to the stage.'"

Also at this event, Timothy Leary voiced his phrase, "turn on, tune in, drop out", that persisted throughout the Summer of Love.[9]

The event was announced by the Haight-Ashbury's psychedelic newspaper, the San Francisco Oracle:

A new concept of celebrations beneath the human underground must emerge, become conscious, and be shared, so a revolution can be formed with a renaissance of compassion, awareness, and love, and the revelation of unity for all mankind.[10]

The gathering of approximately 30,000 like-minded people made the Human Be-In the first event that confirmed there was a viable hippie scene.[11]

The term "Summer of Love" originated with the formation of the Council for the Summer of Love in the spring of 1967 as a response to the convergence of young people on the Haight-Ashbury district. The Council was composed of The Family Dog, The Straight Theatre, The Diggers, The San Francisco Oracle, and approximately twenty-five other people, who sought to alleviate some of the problems anticipated from the influx of people expected in the summer. The Council also supported the Free Clinic and organized housing, food, sanitation, music and arts, along with maintaining coordination with local churches and other social groups to fill in as needed, a practice that continues today.[12]

Popularization

The ever-increasing numbers of youth making a pilgrimage to the Haight-Ashbury district alarmed the San Francisco authorities, whose public stance was that they would keep the hippies away. Adam Kneeman, a long-time resident of the Haight-Ashbury, recalls that the police did little to help; organization of the hordes of newcomers fell to the overwhelmed residents themselves.[13]

College and high-school students began streaming into the Haight during the spring break of 1967 and the local government leaders, determined to stop the influx of young people once schools let out for the summer, unwittingly brought additional attention to the scene, and an ongoing series of articles in local papers alerted the national media to the hippies' growing numbers. By spring, Haight community leaders responded by forming the Council of the Summer of Love, giving the word-of-mouth event an official-sounding name.[14]

The mainstream media's coverage of hippie life in the Haight-Ashbury drew the attention of youth from all over America. Hunter S. Thompson labeled the district "Hashbury" in The New York Times Magazine, and the activities in the area were reported almost daily.[15]

The movement was also fed by the counterculture's own media, particularly the San Francisco Oracle, whose pass-around readership is thought to have topped a half-million at its peak that year.[16]

The media's fascination with the "counterculture" continued with Fantasy Fair and Magic Mountain Music Festival in Marin County and the Monterey Pop Festival, both in June 1967. At Monterey, approximately 30,000 people gathered for the first day of the music festival, with the number swelling to 60,000 on the final day.[17] In addition, media coverage of the Monterey Pop Festival facilitated the Summer of Love even further as large numbers of fledgling hippies headed to San Francisco to hear their favorite bands such as The Who, Grateful Dead, the Animals, Jefferson Airplane, Quicksilver Messenger Service, The Jimi Hendrix Experience, Otis Redding, The Byrds, and Big Brother and the Holding Company featuring Janis Joplin.[18]

"San Francisco (Be Sure to Wear Flowers in Your Hair)"

John Phillips of The Mamas & the Papas wrote the song "San Francisco (Be Sure to Wear Flowers in Your Hair)" for his friend Scott McKenzie. It served well to promote both the Monterey Pop Festival that Phillips was helping to organise, and to popularise the flower children of San Francisco, who came to epitomise the hippy dream.[19] Released on May 13, 1967, the song was an instant hit. By the week ending July 1, 1967, it reached the number four spot on the Billboard Hot 100 in the United States, where it remained for four consecutive weeks.[20] Meanwhile, the song rose to number one in the United Kingdom and most of Europe. The single is purported to have sold over 7 million copies worldwide.[21]

Event

| Part of a series on |

| Love |

|---|

In New York City, an event in Tompkins Square Park in Manhattan on Memorial Day in 1967 sparked the beginning of the summer of love there.[4] During this concert in the park, some police officers asked for the music to be turned down. In response, some in the crowd threw various objects, and thirty-eight police arrests ensued.[4] A debate about the threat of the hippie ensued between Mayor John Lindsay and Police Commissioner Howard Leary.[4] After this event, Allan Katzman, the editor of the East Village Other, predicted that 50,000 hippies would enter the area for the summer.[4]

Double that amount, as many as 100,000 young people from around the world, flocked to San Francisco's Haight-Ashbury district, as well as to nearby Berkeley and to other San Francisco Bay Area cities, to join in a popularized version of the hippie experience.[22] Free food, free drugs, and free love were available in Golden Gate Park, a Free Clinic was established for medical treatment, and a Free Store gave away basic necessities to anyone who needed them.[23]

The Summer of Love attracted a wide range of people of various ages: teenagers and college students drawn by their peers and the allure of joining a cultural utopia; middle-class vacationers; and even partying military personnel from bases within driving distance. The Haight-Ashbury could not accommodate this rapid influx of people, and the neighborhood scene quickly deteriorated, with overcrowding, homelessness, hunger, drug problems, and crime afflicting the neighborhood.[23]

In London

Hot on the tails of being crowned 'Swinging London', the Summer Of Love cemented London's reputation for being a major component of the burgeoning youth movement. And it was in London that the Summer of Love was most keenly experienced. Most of the rest of the country carried on mostly unaware of the changes happening in the capital that summer.

The Summer of Love was centred on some key events and places in London. The UFO Club in Tottenham Court Road, open from December 1966 to October 1967, was a gathering place for the psychedelic crowd, where groups like the Pink Floyd and the Soft Machine played, accompanied by light shows. The Pink Floyd performed their 'Games For May' concert in the Queen Elizabeth Hall in May. The 14 Hour Technicolour Dream in Alexandra Palace on April 29 was another seminal event, where amongst others, The Pink Floyd, The Crazy World of Arthur Brown, Soft Machine, The Move, Tomorrow, and The Pretty Things played.

A Legalise Pot Rally was held at Speaker’s Corner on 16 July, featuring Allen Ginsberg and assorted London policemen.

It was soundtracked by songs such as 'A Whiter Shade of Pale' by Procol Harum, 'Itchycoo Park' by the Small Faces, 'All You Need Is Love' by the Beatles and 'Hole In My Shoe' by Traffic. The Beatles were a major influence, particularly by releasing 'Sgt Pepper's Lonely Hearts Band' on June 1. The mouthpieces for the music were the pirate radio stations, particularly Radio Caroline and Radio London, which introduced the DJ John Peel and his 'Perfumed Garden' show.

Events, attitudes and the zeitgeist were recorded and promoted by the newspaper, International Times, also known as IT, and the magazine, Oz.

Notable graphic artists included Hapshash and the Coloured Coat (who were Nigel Weymouth and Michael English), The Fool (a Dutch group, supported by the Beatles), and Martin Sharp.

Many of the fashion shops, known as boutiques, such as Granny Takes A Trip, Hung On You and Dandie Fashions were centred on the Kings Road. These were where the psychedelic clothing, such as kaftans, Victoriana, mini skirts and everything floral could be found.

Key people included John 'Hoppy' Hopkins, who helped establish the International Times, or IT, which became the voice of the hippie movement. He set up the London Free School, established the UFO psychedelic club and promoted the legendary 14 Hour Technicolor Dream with Barry Miles, a writer who established the Indica Gallery and Bookshop. Paul McCartney was particularly vocal in his support for the new movement.

The establishment was mystified by and frightened of the 'beautiful people', and harassed and arrested them as much as they could, spurred on by the tabloid press. Some notable arrests included Mick Jagger, Keith Richards, Robert Fraser and John 'Hoppy' Hopkins. The Times published an editorial headed ‘Who Breaks A Butterfly On A Wheel?’ denouncing Mick Jagger and Keith Richard's arrest.

Use of drugs

| Part of a series on |

| Psychedelia |

|---|

|

Psychedelic drug use became one of several means of finding or creating a new reality. Grateful Dead guitarist Bob Weir commented:

Haight Ashbury was a ghetto of bohemians who wanted to do anything—and we did but I don't think it has happened since. Yes there was LSD. But Haight Ashbury was not about drugs. It was about exploration, finding new ways of expression, being aware of one's existence.[24]

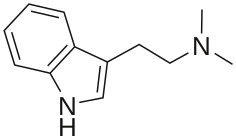

After losing his untenured position as an Instructor on the Psychology Faculty at Harvard, Timothy Leary became a major advocate for the recreational use of the drug, spreading his beliefs up and down the East Coast.[9] After taking psilocybin, a drug extracted from certain mushrooms that causes effects similar to those of LSD, Leary supported the use of all psychedelics for personal development. He often invited friends as well as the odd graduate student to trip along with him and colleague Richard Alpert.

On the West Coast, author Ken Kesey, a prior volunteer for a CIA-sponsored LSD experiment, also advocated the use of the drug.[9] Shortly after participating, he was inspired to write the bestselling novel One Flew Over the Cuckoo's Nest.[9] Subsequently, after buying an old school bus, painting it with psychedelic graffiti and attracting a group of similarly-minded individuals he dubbed the Merry Pranksters, Kesey and his group traveled across the country, often hosting "acid tests" where they would fill a large container with a diluted low dose form of the drug and give out diplomas to those who passed their test.[9]

Along with LSD, cannabis was also used heavily during this period of time. With the various all-organic movements beginning to expand, this drug was even more appealing than LSD because apart from creating a euphoric high, it was all-natural as well. However, as a result, crime rose among users because several laws were subsequently enacted to control the use of both drugs. The users thereof often had sessions to oppose the laws, including The Human Be-In referenced above as well as various smoke-ins in July and August,[25] however, their efforts at repeal were unsuccessful.

Funeral and aftermath

After many people left in the fall to resume their college studies, those remaining in the Haight wanted to signal the conclusion of the scene not only to themselves and their friends, but also to those still in transit or still considering making the trek as well. A mock funeral entitled "The Death of the Hippie" ceremony was staged on October 6, 1967, and organizer Mary Kasper explained the intended message:[14]

We wanted to signal that this was the end of it, to stay where you are, bring the revolution to where you live and don't come here because it's over and done with.[26]

In New York, the rock musical Hair, which told the story of the hippie counterculture and sexual revolution of the 1960s, opened Off-Broadway on October 17, 1967.[27]

Legacy

Second Summer of Love

The Second Summer of Love was a renaissance of acid house music and rave parties in Britain. The culture supported MDMA use and some LSD use. The art had a generally psychedelic emotion reminiscent of the 1960s.[28] The term generally refers to the summers of both 1988 and 1989[29][30]

40th anniversary

During the summer of 2007, San Francisco celebrated the 40th anniversary of the Summer of Love by holding numerous events around the region, culminating on September 2, 2007, when over 150,000 people attended the 40th anniversary of the Summer of Love concert, held in Golden Gate Park in Speedway Meadows. It was produced by 2b1 Multimedia and the Council of Light.[31][32]

Bands/Performers included:

Country Joe McDonald, Taj Mahal, Lester Chambers (from Chambers Brothers), Canned Heat, New Riders of the Purple Sage, Jesse Colin Young (from the Youngbloods), Jerry Miller Band (from Moby Grape) featuring Tiran Porter and Dale Ockerman (from the Doobie Brothers) and Fuzzy John Oxendine (from the Sons of Champlin), Banana (from the Youngbloods), Michael McClure and Ray Manzarek (from the Doors), San Francisco’s First Family of Rock (TBA), Brian Auger, Nick Gravenites Band with David LaFlamme, Dickie Peterson of Blue Cheer, Chris and Lorin of the Rowan Brothers, The Alameda All Stars (from Gregg Allman band), Brad Jenkins, Terry Haggerty (from the Sons of Champlin), Tony Lindsay (Santana), Dan Hicks and the Hot Licks, George Michalski – Pete Sears “Dueling Keys”, Freddie Roulette, Ron Thompson, The Charlatans, Leigh Stephens (Blue Cheer), Greg Douglass (from Steve Miller), Pete Sears (Jefferson Starship), Essra Mohawk (from Mothers of Invention), Barry “The Fish” Melton, All Night Flight featuring David Denny and Steve McCarty (from Steve Miller), Jack King (from Cold Blood) and Dale Ockerman (from Doobie Brothers), Merl Saunders (supporting the event), Squid B. Vicious with Buddy Miles, Jim Post (Friend and Lover, Siegel Schwall Blues Band), David Harris, Fayette Hauser and the Cockettes, Terence Hallinan (former San Francisco DA), Ruth Weiss (Beat Poet), Richard Eastman (Marijuana Initiative), Lenore Kandel (Beat Poet), Paul “Lobster” Wells, Dr Hip (Eugene Schoenfeld), Artie Kornfeld (Producer of Woodstock), Wavy Gravy, Mouse man (Bagpipes), Leigh Davidson (Haight Ashbury Free Medical Clinic), Bruce Latimer (Bruce Latimer Show), Rabbi Joseph Langer, Bruce Barthol (Mime Troupe), Doug Green, Howard Hesseman (schedule permitting), Benjamin Hernandez (Hearts Hands and Elders), American Indigenous Peoples, Agnes Pilgrim and 13 Grandmas (schedule permitting), Lakota War Pony’s, Merle Tendoy (6th generation of Sacagawea) Shonie, Harry Riverbottom (Chippewa), Chief Sunne Reyna, Iroquois Tribe, Dakota Tribe, Seminole Tribe, Emmit Powell and the Gospel Elites, and representatives of the Dalai Lama.[33]

50th anniversary

During the summer of 2017, San Francisco plans to celebrate the 50th anniversary of the Summer of Love by holding numerous events around the region. These are planned to culminate in October, 2017, when over 150,000 people are expected to attend the 50th anniversary of the Summer of Love concert in Golden Gate Park, San Francisco, and webcast/broadcast worldwide. For this 50th anniversary event producers 2b1 Multimedia and the Council of Light are in pre-production, organizing with communities in New York and the UK to plan an event worthy of the occasion. To quote the "Council of Light of 1967-2017", "We call upon the world to celebrate the infinite holiness of Life." [34][35]

See also

- 1967 in music

- John Lennon

- Nick St. Nicholas

- Neil Young

- David Peel

- Hippie

- Grateful Dead

- Deadhead

- Acid rock

- Central Park Be-In

- Commune

- Counterculture of the 1960s

- Allen Ginsberg

- Psychedelia

- Psychedelic rock

References

Notes

- ^ E. Vulliamy, "Love and Haight", Observer Music Monthly 20 May 2007

- ^ P. Braunstein, and M.Doyle (eds), Imagine Nation: The American Counterculture of the 1960s and '70s, (New York, 2002), p.7

- ^ Roots of Communal Revival 1962-1966

- ^ a b c d e Hinckley, David (October 15, 1998). "Groovy The Summer Of Love, 1967". New York Daily News. Retrieved September 28, 2012.

- ^ M. Isserman, and M. Kazin (eds), America Divided: The Civil War of the 1960s, (Oxford University Press, 2004), pp.151–172

- ^ "Chronology of San Francisco Rock 1965-1969". Virtual Museum of the City of San Francisco. Retrieved 2008-11-01.

- ^ "Copy of Certificate of Honor presented to Michael Bowen". City and County of San Francisco. 2007-09-02. Retrieved 2008-11-01.

- ^ T.H. Anderson, The Movement and the Sixties: Protest in America from Greensboro to Wounded Knee, (Oxford University Press, 1995), p.172

- ^ a b c d e Weller, Sheila (July 2012). "Suddenly That Summer". Vanity Fair. Retrieved September 28, 2012.

- ^ San Francisco Oracle, Vol.1, Issue 5, p.2

- ^ T. Gitlin, The Sixties: Years of Hope, Days of Rage, (New York, 1993), p.215

- ^ Summer Of Love ~ The Event

- ^ Stuart Maconie, "A Taste of Summer" broadcast, Radio 2, 9 October 2007

- ^ a b "The Year of the Hippie: Timeline". PBS.org. Retrieved 2007-04-24.

- ^ T. Anderson, The Movement and the Sixties: Protest in America from Greensboro to Wounded Knee, (Oxford University Press, 1995), p.174

- ^ "Summer of Love: Underground News". PBS American Experience companion website. Retrieved 2007-05-15.

- ^ T. Anderson, The Movement and the Sixties: Protest in America from Greensboro to Wounded Knee, (Oxford University Press, 1995), p.175

- ^ T. Gitlin, The Sixties: Years of Hope, Days of Rage, (New York, 1993), p.215–217

- ^ Eddi Fiegel. Dream a Little Dream of Me: The Life of 'Mama' Cass Elliot. pp. 225–226. Retrieved 5 August 2013.

- ^ Whitburn, Joel (2004). The Billboard Book of Top 40 Hits: Eighth Edition. Record Research. p. 415.

- ^ Carson, Jim (August 5, 2011). "Did You You: "San Francisco (Be Sure to Wear Flowers in Your Hair)" By Scott McKenzie". CBS Radio. Retrieved 2012-02-24.

- ^ Allen Cohen

- ^ a b Gail Dolgin; Vicente Franco (2007). The Summer of Love. American Experience. PBS. Retrieved 2007-04-23.

- ^ J. McDonald quoted in E. Vulliamy, , "Love and Haight", Observer Music Monthly, 20 May 2007

- ^ Harden, Mark (July 6, 1997). "Summer of Love Seminal '67 Event Back after 30 Years". Retrieved September 28, 2012.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help)[full citation needed] - ^ "Transcript (for American Experience documentary on the Summer of Love)". PBS and WGBH. 2007-03-14.

- ^ Ron Bruguiere. Collision: When Reality and Illusion Collide. p. 75. Retrieved 5 August 2013.

- ^ Reynolds, Simon (1998). Energy Flash. Picador. ISBN 0-330-35056-0.

- ^ Elledge, Jonn (2005-01-11). "Stuck still". AK13. Retrieved 2006-06-13., "By the end of 1988, the second summer of love was over"

- ^ "History of Hard House". Retrieved 2006-06-13."As the second "Summer of Love" arrived in 1989"

- ^ http://www.2b1records.com/summeroflove40th/FullProc.pdf

- ^ Joel Selvin (September 2, 2007). "Summer of Love bands and fans jam in Golden Gate Park - SFGate". San Francisco Chronicle. San Francisco: Hearst. ISSN 1932-8672. Retrieved 5 August 2013.

- ^ http://www.50thsummeroflove.com/2b1-info/

- ^ http://www.50thsummeroflove.com/

- ^ http://www.50thsummeroflove.com/press/

Further reading

- Lee, Martin A.; Shlain, Bruce (1985). Acid Dreams: The CIA, LSD, and the Sixties Rebellion. New York: Grove Press. IDBN 0-394-55013-7, ISBN 0-394-62081-X.

External links

- Summer of Love: 40 years later, from SFGate, the online publication of the San Francisco Chronicle

- The Summer of Love, Performers in Britain and the United States, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography and the American National Biography

- Long Hot Summer of Love Writer Mark Jacobson reminisces about his experiences during the Summer of Love in New York, from New York magazine

- CIS: 'Summer of Love' Reached Behind Iron Curtain, by Salome Asatiani. RFE/RL, August 30, 2007 (an article about the impact of the Summer of Love event on Soviet youth culture)

- PBS television, The American Experience: Summer of Love, 2007