Trikaya

The Trikāya (Sanskrit: त्रिकाय, lit. "three bodies"; Chinese: 三身; pinyin: sānshēn; Japanese pronunciation: sanjin, sanshin; Korean pronunciation: samsin; Vietnamese: tam thân, Tibetan: སྐུ་གསུམ, Wylie: sku gsum) is a fundamental Mahayana Buddhist doctrine that explains the multidimensional nature of Buddhahood. As such, the Trikāya is the basic theory of Mahayana Buddhist Buddhology (i.e. the theology of Buddhahood).[1]

This concept posits that a Buddha has three distinct "bodies", aspects, or ways of being, each representing a different facet or embodiment of Buddhahood and ultimate reality.[2] The three are the Dharmakāya (Sanskrit; Dharma body, the ultimate reality, the Buddha nature of all things), the Sambhogakāya (the body of self-enjoyment, a blissful divine body with infinite forms and powers) and the Nirmāṇakāya (manifestation body, the body which appears in the everyday world and presents the semblance of a human body). It is widely accepted in Mahayana that these three bodies are not separate realities, but functions, modes or "fluctuations" (Sanskrit: vṛṭṭis) of a single state of Buddhahood.

The Trikāya doctrine explains how a Buddha can simultaneously exist in multiple realms and embody a spectrum of qualities and forms, while also seeming to appear in the world with a human body that gets old and dies (though this is merely an appearance). It is also used to explain the Mahayana doctrine of non-abiding nirvana (apratiṣṭhita-nirvana), which sees Buddhahood as both unconstructed (asaṃskṛta) and transcendent, as well as constructed, immanent and active in the world.[3] This idea was developed in early Yogācāra school sources, like the Mahāyāna-sūtrālamkāra. The doctrine's interpretations vary across different Buddhist traditions, some theories contain extra "bodies", making it a "four body" theory and so on. However, the basic Trikāya theory remains a cornerstone of Mahayana and Vajrayana teachings, providing a comprehensive perspective on the nature of Buddhahood, Buddhist deities and the Buddhist cosmos.[4] The Buddhist triple body theory was also adopted into Daoist philosophy and modified using Daoist concepts.

Overview

[edit]

The Trikāya doctrine sees Buddhahood as composed of three bodies, components or collection of elements (kāya): the Dharma body (the ultimate aspect of Buddhahood), the body of self-enjoyment (a divine and magical aspect) and the manifestation body (a more human and earthly aspect).[7]

The term kāya was understood to have multiple meanings simultaneously. The three main ways it was understood by Indian exegetes were:[8]

- Body as a collection or accumulation of things or parts (Sanskrit: samcaya), mainly referring to the "corpus" of all of Buddha's qualities

- Body as a basis or substratum (asraya) of all phenomena, or as the basis for all the Buddha's qualities.

- Body in the sense of embodiment of the real nature of reality (dharmata)

The relationship among the three

[edit]Mahayana sources emphasize that the three bodies are ultimately not separate from other, that is to say, they are non-dual.[9] However, these different embodiments of the same reality can be described in different ways due to their relative functions or activities (vrttis). Thus, Śīlabhadra's Buddhabhūmi-vyākhyāna states ''the body of the Tathagatas (=dharmakaya), which is the purified dharma realm (dharmadhātuviśuddha), is undivided. However, because it functions as distinguished into three embodiments, it is said to have functional divisions."[10] In Yogācāra literature, the whole unified reality which includes all three embodiments is termed "the purified Dharma-real" (Dharmadhātuviśuddhi), which is the totality of all phenomena as seen by Buddha knowledge.[11]

Furthermore, according to Yogācāra sources like the Madhyāntavibhāga, the non-duality of a Buddha's nirvana also means that Buddhahood is both conditioned and unconditioned at the same time. Thus, the Madhyāntavibhāga says of Buddhahood "Its operation is nondual (advaya vṛtti) because of its abiding neither in saṃsāra nor in nirvāṇa (saṃsāra-nirvāṇa-apratiṣṭhitatvāt), through its being both conditioned and unconditioned (saṃskṛta-asaṃskṛtatvena)."[12] Thus, while there is an element of Buddhahood which is transcendent, free from all worldly conditions and quiescent (dharmakaya), there is also an element which compassionately manifests for the good of all beings and thus is engaged in worldly conditions (the other two bodies).[12] This transcendent and immanent character is described in the Buddhabhūmi-sūtra as follows:

In space, there appear the arising and ceasing of diverse forms. Yet space neither arises nor ceases. Likewise, within the purified dharma realm (dharmadhātuviśuddha) of the Tathagatas, there appear the arising and ceasing of awareness, manifestation, and performance of all the activities for sentient beings. Yet the purified dharma realm has neither arising nor ceasing.[13]

The longer edition of the Golden Light Sutra, which contains a whole chapter on the triple body theory, states that while the manifestation body is singular (appearing as one form, as one being), the enjoyment body is multiple since "it has many forms in accord with the aspirations of beings".[9] Furthermore, the Dharma body is to be understood as neither singular or multiple, "neither the same nor different".[9] The Trikāyasūtra preserved in the Tibetan canon contains the following simile for the three bodies:

the dharmakāya of the Tathāgata consists in the fact that he has no nature, just like the sky. His saṃbhogakāya consists in the fact that he comes forth, just like a cloud. His nirmāṇakāya consists in the activity of all the buddhas, the fact that it soaks everything, just like rain.[14]

Furthermore, this sutra explains that the three bodies can be understood as relative to those who see them:

That which is seen from the perspective of the Tathāgata is the dharmakāya. That which is seen from the perspective of the bodhisattvas is the saṃbhogakāya. That which is seen from the perspective of ordinary beings who conduct themselves devotedly is the nirmāṇakāya.[14]

The Buddhabhūmi-vyākhyāna also explains the bodies through the various types of beings who have access to them in the same way. Only Buddhas see the dharma body, only bodhisattvas see the enjoyment body, and sentient beings are able see the manifestations.[3] The Golden Light sutra also associates different kinds of wisdom to each body and with the different elements of the eight consciousnesses. The Dharma body is the mirror-like wisdom (ādarśajñāna), the pure state of the "basis-of-all" (alaya); the enjoyment body is discriminating wisdom (pratyavekṣaṇājñāna), the pure state of mental cognition; while the nirmāṇakāya is "all-accomplishing wisdom" (kṛtyānuśṭhānajñāna), which is the pure state of the five sense consciousnesses.[14]

Dharmakāya

[edit]

The Dharmakāya (Ch: 法身; Tib. chos sku; "Dharma body," "Reality body", "Truth body"; sometimes also called svabhāvikakāya - the intrinsic body) is often described through Buddhist philosophical concepts that describe the Buddhist view of ultimate reality like emptiness, Buddha nature, Dharmata, Suchness (Tathātā), Dharmadhatu, Prajñaparamita, Paramartha, non-duality (advaya), and original purity (ādiviśuddhi).[18][19][2][5][20] The Dharmakāya is also associated with the "body of the teachings", that is to say, the Buddhadharma, the teachings of the Buddha, and by association, with the nature of reality itself (i.e. the Dharma and the nature of the dharmas - all phenomena), which the teachings point to and are in accord with.[21]

In several Mahayana sources, the Dharma body is the primary and ultimate Buddha body, as well as "the foundation and basis for the two other bodies" according to Gadjin Nagao.[20] For example, the Golden Light sutra states that:

The first two bodies are merely designations, while the Dharma body is true and the basis for those two other bodies. Why is that? It is because there is only the true nature of phenomena and nonconceptual wisdom, and there are no other qualities that are separate from all buddhas. All buddhas have a perfection of wisdom, and all their kleśas have completely ceased and ended so that the buddhas have attained purity. Therefore, all buddha qualities are contained within the true nature and the wisdom of the true nature.[9]

The Dharma body embodies the true nature of Buddhahood itself and all its inconceivable powers and qualities.[9] It is generally understood as impersonal, without concept, words or thought. Even thought it is without any intention or thought, it accomplishes all Dharma activities spontaneously.[9] Indeed, various Mahayana sources describe the Buddha bodies are being without thought or cognition. The Golden Light Sutra uses the analogy of the sun, moon, water, mirrors and light, which are without thought and yet they cause reflections to appear: "in the same way that through a combination of factors the reflections of the sun and moon appear, through a combination of factors the enjoyment bodies and the emanation bodies manifest their appearances to beings who are worthy."[9]

The Dharma body is also the true nature of all things (dharmas) and the true nature of all beings, equivalent to the Mahayana concept of emptiness (śūnyatā), the lack of inherent essence in all things.[22] It is permanent, unceasing and unchanging.[23] According to the Laṅkāvatāra Sūtra:[24]

Dharmata-Buddha is Buddhahood in its self-nature of perfect oneness in whom absolute tranquillity prevails. As Noble Wisdom, Dharmata-Buddha transcends all differentiated knowledge, is the goal of intuitive self-realisation, and is the self-nature of the Tathagatas. As Noble Wisdom, Dharmata-Buddha is inscrutable, ineffable, unconditioned. Dharmata-Buddha is the Ultimate Principle of Reality from which all things derive their being and truthfulness, but which in itself transcends all predicates. Dharmata-Buddha is the central sun which holds all, illumines all.

The Dharma-body is often described in apophatic terms (especially in Madhyamaka sources), as formless, thought-less and beyond all concepts, language and ideas - including any idea of existence (bhava) or non-existence (abhava), or eternalism (śāśvata-dṛṣṭi) and annihilation (ucchedavāda).[25] The Golden Light Sutra says:

Noble one, the Dharma body is revealed nonduality. What is nonduality? In the Dharma body, there are neither characteristics nor the basis for characteristics, and so there is neither existence nor nonexistence; the Dharma body is neither single nor diverse; it is neither a number nor numberless; and it is neither light nor darkness.[9]

According to Paul Williams, the Hymn to the Ultimate (Paramārthastava) by Nagarjuna describes the Buddha in negative terms. Buddha is thus beyond all dualities, "neither nonbeing nor being, neither annihilation nor permanence, not noneternal, not eternal."[25] He is without color, size, location, and so on.[25] Because of this negative buddhology that is often used to describe the Dharmakaya, it is often depicted with impersonal symbols, like the letter A, some other mantric seed syllable, the disk of the moon or sun, space (Sanskrit: ākāśa), or the sky (gagana).[5][6] However, iconic representations of the Dharmakaya are also common, as with the depiction of the Buddha Mahavairocana in East Asian esoteric Buddhism and the Buddha Vajradhara or Samatabhadra in Tibetan Buddhism.[18]

In Indian Yogācāra school sources, the Dharmakāya is sometimes described in more positive ways. According to Williams, Yogācāra sees the Dharmakāya as the support or basis of all dharmas, and as being a self-contained nature (svabhāva) which lacks anything contingent or adventitious.[22] It is thus "the intrinsic nature of the Buddhas, the ultimate, the purified Thusness or Suchness " and "the true nature of things taken as a body", a non-dual, pure and immaculate wisdom.[22] A related term used to describe Buddhahood in Yogācāra is the natural luminosity of the mind (cittam prakṛtiśprabhāsvaram)[26] According to the commentary to the Dharma-dharmatā-vibhāga: "although there has been a "fundamental transformation" (āśraya-parāvṛtti) [at full enlightenment], nothing has undergone an actual change"[27] This innate nature is then compared to the sky, which is always pure, but can be covered by clouds which are only adventitious. It is also compared to water, which may get muddy, but its nature remains clear and pure. However, "when the [innate luminosity] is freed from those [obstructions], it appears." As such, the dharmakaya is never generated or created, and is thus permanent (nitya).[27]

The Yogācāra also sees the Dharmabody as equivalent to the dharmadhātu (the totality of the cosmos) in its ultimate sense, in other words "the intrinsic body of the Buddha is the intrinsic or fundamental dimension of the cosmos".[28] According to Yogācāra, on this ultimate level, there is no distinction between different Buddhas, there is only the same non-dual reality beyond all concepts including singularity and multiplicity.[28] This also means that a Buddha's knowledge is all pervasive. Since Buddha's knowledge knows the true nature of all things and is conjoined with the true nature of all things, it pervades the entire world, and thus its functions are operative throughout the entire cosmos according to beings' needs. The Buddhabhūmi-sūtra compares the omnipresence of the Buddha's knowledge to how space pervades all things.[29] Furthermore, Yogācāra sources indicate that the dharma body is beyond the understanding of any being that is not a Buddha, describing it as inconceivable (acintya), subtle (suksma), difficult to know, "inaccessible to speculative investigation", and "beyond ascertainment by reason."[30]

The Golden Light Sutra also describes the Dharma body in positive terms as well, using various terms for it including: "the pure field of experience and pure wisdom", "the nature of the tathāgatas, "the essence of the tathāgatas". The Sutra also describes it using the perfections used to describe Buddha nature in other sources: eternal (nitya), self (ātman), bliss (sukha), and purity (śuddha).[9] [31]

In the Xuanzang's Chengweishilun (Treatise Demonstrating Consciousness-only), the Dharmakaya (also called here the vimuktikaya, body of liberation) is described as what is adorned with the great Buddha qualities (mahāguṇa), which are conditioned and unconditioned, immeasurable, and infinite.[32] It also describes the dharmakaya-svabhāvikakāya as the real nature of the Buddhas and all dharmas, "the real pure dharmadhatu", the "immutable support" of the two other bodies, which is peaceful, beyond all prapañca, neither matter (rupa) nor mind (citta). It is "endowed with real, permanent qualities", and is permanent, blissful, sovereign, pure, infinite and all pervasive ("extends everywhere").[32] Xuanzang also states that the svabhāvikakāya "is common to all tathagatas" and that it is "realized in the same way by all the tathagatas" since there is "no difference possible between the self-nature body of one buddha and that of the other buddhas".[33]

Saṃbhogakāya

[edit]

The Saṃbhogakāya (Ch: 報身, 受用身; Tib. longs sku) refers to the divine magical bodies of the Buddhas which manifest for the benefit of noble bodhisattvas.[2][28] It can be rendered as "co-enjoyment body", and "communal bliss body" (when reading the prefix saṃ- to refer to ‘together with’ or ‘mutual’) or as "complete reward body", "total enjoyment body" (reading saṃ- as "complete", "thoroughness").[34] The Saṃbhogakāya is described by the Mahāyāna-sūtrālamkāra as that which "brings enjoyment of dharma to the circles of assembly."[35] The term is usually associated with more supramundane, cosmic or otherworldly Buddhas.[18][36] For example, Sthiramati names Vairocana, Amitabha and Samantabhadra as Saṃbhogakāya Buddhas.[37]

While this aspect of Buddhahood does appear to have a kind of form, it is a form that transcends the three worlds and all material existence.[28] As such, only advanced bodhisattvas and beings in the pure lands receive teachings directly from the Saṃbhogakāya in standard Mahayana doctrine. As the Golden Light Sutra says, the Saṃbhogakāya "is a body that is seen on the bhūmis."[38] That is to say, one must have entered the bodhisattva stages or the pure lands to see it.[20] Thus, the enjoyment body has a middle position between the more human manifestation body and the totally formless Dharmakaya.[20]

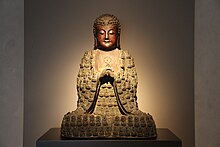

This body is the object of popular Buddhist devotion in Mahayana Buddhism, it is the Buddha as an omniscient transcendent being with immense powers, animated only by universal compassion for all living things.[39] The Buddha's enjoyment body also has a very unique appearance, made up of the 32 major marks of great man. These characteristics include such unusual features as dharma wheels on the soles of his feet, glowing golden skin, unnaturally long tongue and arms which extend to his knees, and unique facial features like the uṣṇīṣa (a fleshly dome on top of his head) and ūrṇākośa (circle of hair between his eyebrows).[40][20]

Some Yogācāra sources, like Xuanzang’s Chengweishilun and Bandhuprabha's commentary to the Buddhabhūmi-sūtra, describe the enjoyment body as having two aspects: a private aspect which is experienced by Buddhas themselves "for their own enjoyment" (自受用身) and an aspect manifested for the sake of others' benefit (他受用身).[39] Xuanzang explains these as follows:

- Body of enjoyment for oneself (sva-saṃbhogakāya): "the infinite real qualities brought forth by the accumulation of merit and knowledge (puṇya-jñāna-saṃbhāra) cultivated by Tathagatas during three innumerable aeons along with perfect, pure, permanent omnipresent material body". It forms a single mental stream but it remains the same, is permanent, omnipresent, and "will last until the end of time". Xuzanzang also writes that it "constantly enjoys itself in the vast bliss of the great Dharma".[41] It also contains all the unique qualities of a Buddha (āveṇika) and is made up of a kind of subtle matter.[42] Furthermore, it's knowledge also forms an eternal perfect pure land where the sva-saṃbhogakāya resides permanently. Also, since the dhamakaya extends everywhere and it is the support of the sva-saṃbhogakāya, the sva-saṃbhogakāya also extends everywhere.[43]

- Body of enjoyment for others (para-saṃbhoga-kāya): "this means that the tathagatas, by means of the knowledge of equality (samatā-jñāna) manifest a body endowed with subtle and pure qualities, which inhabits a completely pure land; thanks to the knowledge of discernment, this body - for the benefit of bodhisattvas residing in the ten stages - displays great spiritual powers or masteries, turns the wheel of the Dharma, cuts the nets of doubts, in such a manner that these bodhisattvas enjoy the bliss of the Dharma."[44] However, these bodies and pure lands are not the real body of knowledge (jñāna) of the Buddha like the sva-saṃbhogakāya, they are utimately just fully pure manifestations and are relative to the needs of sentient beings.[45]

In other words, the private aspect of co-enjoyment is associated with the blissful reward of Buddhahood experienced by Buddhas themselves, also called “the Buddha’s own enjoyment of the dharma-delight”.[20] This embodies the idea of reaping the benefits or rewards of spiritual practice and dwelling in sublime states of realization. The public aspect of "enjoyment for others" is associated with sharing the Dharma with other beings, with divine pure lands (buddha-fields) which are extensions of the enjoyment bodies themselves, as well as with all the numerous emanations which are manifested by the saṃbhogakāya as a skillful means to guide different types of beings.[20] It is considered a skillful manifestation that arises as a result of fulfilling vows and commitments on the long bodhisattva spiritual journey.[46]

Nirmāṇakāya

[edit]

The Nirmāṇakāya (Ch: 化身, 應身; Tib. sprul sku; the body of transformation, emanation, manifestation or appearance) is a reflection of the Saṃbhogakāya, one of the myriad magical manifestations created by the Saṃbhogakāya.[47] It is also called rūpa-kaya, the "form body" or "physical body". The Nirmāṇakāya generally refers to a Buddha's human-like appearance in imperfect worlds like ours, which appear for limited periods of time and seemingly die in paranirvana. It is usually associated with "historical" Buddha figures, like Shakyamuni Buddha.[2] It is thus the most historic, temporally and spatially contingent, and humanistic aspect of the three bodies.[20]

According to the Golden Light sutra, the Buddhas know the aspirations, conduct, nature and needs of all beings, and thus they "they teach the appropriate Dharma in accordance with the time and with those types of conduct". To do this, they manifest various types of bodies, and these are called the Nirmāṇakāyas.[9] Similarly the Laṅkāvatāra Sūtra states that the Nirmana Buddhas appear as skillful means for the liberation of all beings.[24] According to the Abhisamayālaṅkāra:

[The embodiment of the Sage] in his manifestation(s) (nairmāṇikakāya) is that through which he impartially carries out diverse benefits for the world. It is uninterrupted for as long as the existence [of the world]. Likewise, it is agreed, its activity (karman) is uninterrupted for as long as cyclic existence last... (AA 8.33) [48]

Manifestation bodies allow Buddhas to interact with and teach sentient beings in a more direct and human manner. They typically appear as male monastics in most Mahayana sutras, though later they encompassed all sorts of bodies. This earthly embodiment serves as a bridge between the divine and the human realm. It makes the teachings and compassion of a Buddha accessible to beings of impure realms who seek guidance from an awakened being. However, even this more human-like Buddha is not just a normal human body. A Nirmāṇakāya only appears human, in reality it is just a phantom like magic body, a mere docetic appearance, which can perform many magic powers and which only appears to die.[49]

Xuanzang's Chengweishilun defines the emanation body as the method used by Buddhas through their knowledge of accomplishing actions (kṛṭya-anuṣṭhāna-jñāna) to create "innmumerable and varied" transformations "which inhabit pure or impure lands". This is for the benefit of bodhisattvas who have not yet attained the bodhisattva stages, for followers of the two vehicles, and for ordinary people. These bodies are varied and take into account the needs of all the different types of beings.[44] He further states that Nirmāṇakāyas "are not real minds (cittas) and mental factors (caittas)", they only appear as having minds.[50]

To the question of what happens when someone is devoted to and relies on several Buddhas at the same time, Xuanzang responds that "at the same time and in the same place, each of these buddhas develops as a body of emanation (nirmāṇakāya) and as a land", in other words all these buddhas becomes the condition "which causes the person to be converted (or instructed) to see such a body of emanation."[51]

Nirmāṇakāyas often appear in a world to turn the wheel of Dharma (i.e. teach Buddhism) and to display the twelve great acts of a Buddha (such as miraculous birth, renunciation, defeating Mara, enlightenment under a bodhi tree, etc) and they also may found a Sangha which maintains the teaching even after the Nirmāṇakāya has manifested nirvana.[39] However, this is not always the case, and a Nirmāṇakāya may perform unusual acts, like teaching non-Buddhist teachings or appearing as an animal (as in the Jatakas) for example, if this is the skilful means that is required to teach certain beings.[39]

Historically, the form body of the Buddha was also associated with specific stupas, where the relics of the historical Buddha's body were believed to have been located.[52]

Indian Buddhist history

[edit]

The concept of two Buddha bodies - physical and Dharma body, appears in non-Mahayana Buddhist sources, like the Early Buddhist texts, and the works of the Sarvastivada school. In this non-Mahayana context, Dharmakāya referred to the "body of the teachings", the teachings of the Buddha in the Tripitaka and their final intent, the ultimate nature of the dharmas.[21] It could also refer to the set of all dharmas (phenomena, attributes, characteristics) that was possessed by a Buddha, i.e. "those factors (dharmas) the possession of which serves to distinguish a Buddha from one who is not a Buddha."[53]

In the earliest Buddhist sources (the Pali suttas, the Agamas), the term dharmakaya appears rarely and it refers to the body of the Buddha's teachings.[54]

For the Sarvastivada school and its associated northern Abhidharma traditions, this "body of dharmas" (Buddha's teachings and buddha-qualities) was the highest and true refuge, which does not pass away like the Buddha's physical body.[21] Thus, the Abhidharmakośa says:

One who goes to the Buddha for refuge goes for refuge to the fully accomplished qualities (asaiksa dharmah) that make him a Buddha; [the qualities] principally because of which a person is called "Buddha"; [the qualities] by obtaining which he understands all, thereby becoming a Buddha. What are those qualities? Ksayajñana [knowledge of the destruction of the passions], etc., together with their attendants.[55]

According to Yasomitra's commentary some of the key qualities include ksayajñana (knowledge of the destruction of the defilements), anutpadajñana ("knowledge of the non-arising" of defilements), samyagdrsti (right view), and the five undefiled aggregates: sila (virtue), samadhi (concentration), prajña (discernment), vimukti (liberation), and vimuktijñanadarsana (the vision of the knowledge of liberation).[56]

Furthermore, in Abhidharma texts like the Abhidharmakośa and the Mahāvibhāṣa Śāstra, dharmakaya also includes the eighteen special qualities of a Buddha (āveṇikadharmaḥ), which are: the ten powers, four forms of fearlessness, great compassion, and the three mindful equanimities.[57] The Abhidharmakośa lists even more qualtities, such as: the four pratisamvid (analytical knowledges), the six abhijñas (supernatural knowledges), the four dhyanas (meditative absorptions), the four arupyasamapattis (formless meditative states), the four apramanas (measureless thoughts), the eight vimoksas (liberations), the eight abhibhvayatanas (bases of overcoming), the thirty-seven bodhipaksas (factors that foster enlightenment) and more.[58] All these various qualties would later be adopted into the Mahayana understanding of a Buddha's qualities and they regularly appear in various listings found in Mahayana sutras like the Prajñāpāramitā sutras.[58]

The concept of two bodies was also adopted by the Southern Theravada school. This can be seen in the works of Buddhaghosa, who writes:

That Bhagavat, who is possessed of a beautiful rupakaya, adorned with thirty major and eighty minor marks of a great man, and possessed of a dhammakaya purified in every way and glorified by sila, samadhi, pañña, vimutti and vimutti-ñana-dassana, is full of splendour and virtue, incomparable and fully awakened.[59]

This set of five qualities, the "fivefold dharmakaya" is also found in other sources, like in the Ekottaragama, which also mentions a dharmakaya composed of discipline, samadhi, wisdom, liberation and "the vision of knowledge and liberation" (vimukti-jñana-darshana).[60]

Two bodies in Indian Mahayana

[edit]Early Mahayana sutras like the Aṣṭasāhasrikā Prajñāpāramitā (c. 1st century BCE) and the Lotus sutra, also mostly follow this basic model of two bodies: the body of Dharma and the form body (rūpa-kaya).[53][20] According to the Aṣṭasāhasrikā Prajñāpāramitā, only fools think of the Buddha as being his physical body, since their real body is the dharmakaya.[53] Thus, while the Buddha's physical body died, the body of Dharma never dies, it is imperishable.[20] This referred to both his teachings as well as the ultimate natural law of reality, dependent arising, which was equivalent to emptiness in Mahayana.[20] The Aṣṭasāhasrikā also says that prajñāpāramitā is "the real relic/body of the Tathagatas (Tathāgatanam Śarīram)" and that it is both ultimate reality and the main basis for attaining ultimate reality:

As the Bhagavan has said: "The Buddhas, the Bhagavans, are those who have dharma as body (Dharmakāya). But, monks, you should not think that this [physical] body is my actual body. Monks, you should perceive me through the full realization of the body which is dharma (Dharmakāya)." And one should see that this, the [actual] body of the Tathāgatas, is brought about by the limit of reality (Bhūtakoṭiḥ), i.e., the perfection of wisdom (Prajñāpāramitā).[61]

In another passage, the Aṣṭasāhasrikā identifies the Buddha with the real nature, dharmataya, which is unmoving, non-arising (anutpada), emptiness, the thusness of dharmas (dharmam tathātā) which has no enumeration or division. Thus, the meaning of dharmakaya here becomes "the embodiment of Dharmata". The sutra also compares those who think the Buddha is his physical body to those who mistake a mirage for water, thinking there is water where there is none.[62]

The Aṣṭasāhasrikā describes Buddha's true body, and thus the tathatā (thatness, suchness) of all things, in various ways:[63]

- tathatā has no coming or going, no change

- it is eternal and undifferentiated

- it is neither existent nor non-existent

- it is unhindered / not blocked by anything

- it is unmade, non-arising, unceasing, indestructible, and unsupported

- it is neither apart from nor the same as all dharmas (phenomena)

- it transcends all time, it has no past, present, or future

- it has no specific characteristics or distinguishing marks (lakṣaṇa), such as colour, shape, etc.

- it is beyond thought, indescribable, and non-conceptual

Furthermore, the Prajñāpāramitā sutras reject even the Abhidharma view that the undefiled Buddha qualities (like the ten powers etc.) are the true Buddha body since all dharmas are empty and lack self-existence (svabhava). Only the real nature of things and the non-dual wisdom that sees it comprise the true Buddha body. Thus, in the Prajñāpāramitā in 700 slokas, Mañjusri states that he does not reflect on any of the Buddha qualities since "the development of perfect wisdom (prajñāpāramitā) is not set up through discriminating any dharma".[64] The Pañcaviṃśatisāhasrikā Prajñāpāramitā similarly states: "Whether there is a Buddha or not, the dharmatā abides in the tathatā, and the dharmatā is the dharmakāya."[65]

Some scholars like Yuichi Kajiyama have argued that this sutra's critique of people who think the Buddha is to be found in his physical body is a criticism of stupa worship, and that the Perfection of Wisdom sutra was attempting to replace stupa worship with worship of the Perfection of Wisdom itself.[66] Some scholars think that the Mahayana idea of the Dharma body evolved over time to signify the ultimate reality itself, the Dharmata (Dharma-ness), the emptiness of all dharmas, and the Buddha's wisdom (prajñaparamita) which knows that reality.[66]

While the Prajñāpāramitā sutras outline lists of the Buddha's pure dharmas (anāsravadharmaḥ), they do not see them as the defining feature of Buddhahood, as Abhidharma schools do, since in Prajñāpāramitā literature, all dharmas are empty. Instead, the defining feature of a Buddha in the Prajñāpāramitā sutras is the wisdom which knows the emptiness of all dharmas (which is prajñāpāramitā, the perfection of wisdom). It is this non-dual wisdom, as well as emptiness (śūnyatā) itself, that comes to be identified with the term dharmakāya in the Prajñāpāramitā sutras.[67]

While the Prajñāpāramitā sutras mostly focus on the apophatic nature of the dharmakaya, other sutras offered different perspectives. By the time of the Avatamsaka sutra, the dharmakaya had come to be seen as a cosmic principle which is also "the treasure house of the great wisdom and immeasurable virtues" of the Buddha.[68] The Avatamsaka states: "The dharmakaya of the Tathagata is equal to the dharmadhatu [cosmos] and manifests itself according to the inclinations of sentient beings for their specific needs."[69] The Avatamsaka also claims all Buddhas are the same dharmakaya: "The bodies of all Buddhas are but one dharmakaya, one mind and one wisdom."[70] Furthermore, while the Avatamsaka affirms that the dharmakaya has "no form, no shape and not even the shadow of images", it also states that "it can manifest itself in various forms for the many different kinds of sentient beings, allowing them to behold it in accordance with their mentality and wishes."[68]

Furthermore, in the Buddha-nature sutras, like the Tathāgatagarbhasūtra and the Śrīmālādevīsiṃhanādasūtra, the dharmakaya is identified with buddha-nature.[71] In the Nirvana Sutra, the two bodies are explained and the dharmakaya is said to be infinite and unbreakable like vajra, and thus is also called the great self.[72] It is also said to have the four perfections (which are also said to be those of the buddha-nature):

The rupakāya is the body of transformation manifested by skilful means and this body can be said to have birth, old age, sickness and death . . . The dharmakāya has [the attributes of ] eternity (nitya), happiness (sukha), self (ātman) and purity (śubha) and is perpetually free from birth, old age, sickness, death and all other sufferings . . . It exists eternally without change whether the Buddha arises or not in the world.[73]

Regarding the nirmāṇakāya as a docetic magical transformation, Guang Xing argues that this has its roots in the early Buddhist idea that the Buddha can manifest various mind-made magical bodies (manomayakāya) through his magical powers (ṛddhi), and can thus take any shape or multiply his body as many times as he wants.[74] The Mahāsāṃghika school meanwhile, argued that all bodies of the Buddha which had appeared in this realm had been magical bodies (mayakāyas) displayed by the Buddha. The Mahayana school readily adopted this docetic buddhology, and it is apparent in some of the Prajñāpāramitā sutras.[75]

However, the term nirmāṇakāya is first used in other sutras, like in the "Manifestation of the Tathagata" (a sutra that came to be incorporated into the Avatamsaka sutra), which also uses other less common terms like constructed body, body of merit, "body in accordance with the situation", etc.[75] Other chapters of the Avatamsaka state that the Buddha can manifest oceans of nirmāṇakāyas, as many as all the atoms in the universe. The sutra also compares the various manifestation bodies to the many reflections of the same moon (dharmakaya).[76]

Three bodies in Indian Mahayana

[edit]

Later Mahayana sources introduced the Sambhogakāya, which conceptually fits between the Nirmāṇakāya (the physical manifestation of enlightenment) and the Dharmakaya. Makransky also notes that one reason the doctrine developed was to explain the nature of nirvana, specifically the Mahayana doctrine of non-abiding nirvana (apratiṣṭhita-nirvana). This central Mahayana idea states that nirvana is considered to be an unconditioned state, but it also is supposed to be a state which allows a buddha to act in the conditioned world for the benefit of all berings. As such, the trikaya provides an explanation of how a Buddha is both free of all conditions and transcendent, while also being able to be immersed in the conditioned world to manifest many skillful means for the good of all.[3] Guan Xing meanwhile argues that the sambhogakāya concept likely developed out of the idea that the Buddha had attained immense amounts of merit (punya) due to his eons of bodhisattva practice, and thus he must have achieved a correspondingly immeasurable divine body.[77] By the time the mature Sambhogakāya concept was developed in the Yogacara treatises, it had absorbed all the various transcendent qualities that had been attributed to the Buddha in the Mahayana sutras, such as his boundless light, limitless life-span and power.[78]

An early conception of the three bodies (with alternate names: Dharmata Buddha, Niṣyanda Buddha, and Nirmāṇa Buddha) appears in the Laṅkāvatāra Sūtra.[24] According to D.T. Suzuki, the Laṅkāvatāra is the one of the earliest sources for a three body theory, and the Niṣyanda (flowing, streaming, gushing) Buddha can be considered early form of the Sambhogakāya, though conceptually it is focused on the functions of the Buddha (which "flow" out of his nature).[77]

The mature three bodies theory developed in the Yogācāra school (in around the 4th century) and can be seen in sources like the Mahāyāna-sūtrālamkāra (and its commentary) as well as Asanga's Mahāyānasaṃgraha.[79][22][80] The theory of the three bodies also appears in several Mahayana sutras. For example, the later editions of the Golden Light Sutra contain a chapter on the three bodies (but not the earliest twenty one chapter version).[81]

In these later sources, the Nirmāṇakāya retains the old meaning of a Buddha's many manifested bodies as seen by normal beings, while the Sambhogakāya is used to explain the more exalted and cosmic aspects of a Buddha which appear in Mahayana sutras.[82] One of the earliest Yogācāra accounts appears in the Mahāyāna-sūtrālamkāra (MSA). According to the MSA, "all phenomena are Buddhahood, because thusness has no differentiation" and Buddhahood is ultimately "the purity of thusness" (tathatavisuddhi), the pure nature of all dharmas, of all things (dharmakaya). However, in Buddhahood there are no phenomena (of the imagined nature), there are only excellent qualities, "but it is not defined by them", since they are not ultimately real (i.e. they are empty). As such, the true Buddhahood is the pure dharmata, the nature of things, and yet, this is non-dual with all phenomena as well and with the non-dual wisdom which knows it, i.e. the perfected nature (parinispanna) in Yogācāra's three nature schema. This means all phenomena (dharmas) are identified with Dharmakaya (their thusness and the non-conceptual buddha knowledge, nirvikalpajñana) and yet also negated (as imagined phenomena do not exist ultimately).[83]

The MSA then explains that a Buddha has a threefold function or "fluctuations" (vrtti): the embodiment in manifested forms (nairmanikakaya) which teach living beings, the embodiment of communal enjoyment (sambhogikakaya) which teaches great bodhisattvas, and the dharmakaya as the inner realization of a Buddha.[11] Or as the MSA itself states:

Embodiment of the Buddhas is threefold, [being]: (1) In its own essence (svabhavika), the embodiment of dharma (dharmakaya), whose identity is fundamental transformation (asrayaparavrtti); (2) in communal enjoyment (sambhogika), that which creates enjoyment of dharma within the circles of [the bodhisattva] assembly; (3) in manifestation (nairmanika), manifestation(s) that work for the benefit of beings. (MSA 9.60 bhasya) [84]

Dharmakaya is the essence of Buddhahood (svabhava, synonymous with svabhavikakaya), the pure nature and the buddha wisdom (tathatavisuddhi and nirvikalpajñana), and thus is invisible to anyone but the Buddha.[85] The term "fundamental transformation" or "revolution of the basis" (āśraya-parāvṛtti) indicates that the a key element of Buddhahood's essence is its aspect as a totally purified and perfected (paranispanna) nature, i.e. the Buddha's non-dual knowledge (which transcends any sense of self, or of subject and object). This is identified with other terms like the undefiled realm (anasrava-dhatu) and the purified dharma realm.[86]

When Buddhas appear to others, they appear as Sambhogakāya and Nirmāṇakāyas.[85] All three "embodiments", along with their activities, qualities and essence, correspond to "the purified dharma realm" (dharmadhatu-visuddha). Makransksy defines it as "the nature of all phenomena as embraced by the unobstructed nondual awareness, the gnosis, of a Buddha (jñana). It is Buddhahood in its fullest, cosmic dimension: the totality of all phenomena as viewed through a Buddha's nondual awareness of their true nature."[11] In some Yogacara sources, the term Dharmakaya also referred to this pure realm, and thus the term dharmakaya could have two meanings: the most fundamental of the three bodies, and the totality of all three embodiments of buddhahood.[85] Initially, in texts like the MSA, the term svabhāvikakāya referred to the exclusive meaning (the most fundamental embodiment) while dharmakaya referred to the second comprehensive meaning. In later commentarial sources however, the term svabhāvikakāya was dropped and the term dharmakaya was used to refer to both meanings in different contexts.[87]

Furthermore, according to Makransky, in this early formulation, there are not really three different "bodies", instead there is ultimately one "insubstantial, unlimited, and undivided" purified dharma realm that all Buddhas share and which is embodied in three modes. This non-dual awareness of thusness is only distinguished "with reference to the distinct ways in which that undivided realization functions (vrtti) for those who have it (the Buddhas) and for those who do not (non-Buddhas)."[88] This view of the three "embodiments" as modes of a single reality is also found in the Buddhabhumivyakhyana, a commentary to the Buddhabhūmi Sūtra.[89]

Four body theories

[edit]

Certain Indian sources teach a slightly different Buddha body model which has a fourth body. A major controversy arose among later Indian Mahayanists over the interpretation of the Buddha body theory. At the crux of the issue was the interpretation of the eighth chapter of the Abhisamayalankara (c. between the fourth and the early sixth centuries C.E), a treatise on the Prajñaparamita sutras.[90]

Arya Vimuktisena's commentary on the Abhisamayalankara (ca. early sixth century, the earliest such commentary) interprets the eighth chapter of the work with a classic three body model. This model was followed by later exegetes like Ratnākarāśānti.[91] By contrast, the 8th century Buddhist thinker Haribhadra (c. 8th century) argues in his commentary to the Abhisamayalankara that Buddhahood is best understood to have four bodies: svābhāvikakāya, [jñāna]-dharmakāya, sambhogakāya and nirmāṇakāya.[91]

According to John J. Makransky, the basic disagreement between these interpretations was not so much on the total number of bodies as on the actual meaning of the terms svābhāvikakāya and dharmakāya. According to Arya Vimuktisena, svābhāvikakāya and dharmakāya refer to the same thing, "the essential nondual realization of Buddhahood".[92] Haribhadra meanwhile did not see these two terms are referring to the same thing. Initially this position was not widely accepted, but over time it was popularized by figures like Prajñakaramati (ca. 950-1000 C.E.).[92]

For Haribhadra, svābhāvikakāya was "the unconditioned aspect by which a Buddha transcends the conditioned world of delusion" and is thus the true ultimate. Meanwhile, the jñānātmaka-dharmakāya was "the conditioned aspect through which he appears to beings within their world of delusion to work for them", in other words, the Buddha wisdom (buddhajñāna) and undefiled dharmas, which are still impermanent and relative.[93] According to Makransky, Haribhadra's model is an implicit critique of the Yogacara three body theory, which equates Buddha wisdom and emptiness (placing both in the Dharmakaya category), which a Madhyamika like Haribhadra could not accept (since he held even wisdom was conditioned and impermanent).[94] Furthermore, as Makransky writes, for Haribhadra the Yogacara model gave rise to a logical tension because it failed to distinguish separate ontological bases for the transcendence and immanence of Buddhahood. Thus, he sought to divide the Dharmakaya aspect into two: "an unconditioned, transcendent aspect and a conditioned, immanent aspect," and as such, make the Buddha body theory more logically consistent with classic Buddhist reasoning.[95]

Makransky also writes that "although Haribhara's interpretation of AA 8 is brilliant, it is neither philologically nor historically accurate." A more accurate interpretation of the Abhisamayalankara's eighth chapter, according to Makransky, is Arya Vimuktisena's three kaya view, since it matches a straightforward and historical reading of the text as a Yogacara work.[96]

The four body view was widely debated in Indian Buddhism and in Tibetan Buddhism, where different schools and thinkers take different positions on the matter.[91] Later Indian thinkers like Ratnākarāśānti and Abhayakaragupta were very critical of Haribhadra's interpretations.[97] Ratnākarāśānti sharply disagrees with Haribhadra's view that human reasoning can ever accurately represent the nature of Buddhahood. For him, only yogic attainment can truly see the non-conceptual and non-dual nature of Buddhahood. As such, any logical tension perceived by Haribhadra in the three body theory was not a problem to be solved, but simply a limitation of thought. Logic can never reach the ultimate which transcends all dichotomies and reasoning itself.[98] Because of this, Ratnākarāśānti also critiques Haribhadra's very understanding of the Abhisamayalankara's presentation of dharmakaya as a systematic buddhology. Instead of providing coherent and logical model of Buddhahood, Ratnākarāśānti reads this text's exposition of the dharmakaya as pointing to the Buddha's own experience, which is beyond all thought or reason, and yet can only express itself to beings like us through dualistic and seemingly logically fraught means.[99] As such, the logical tension found in the teaching of the dharmakaya as being immanent and transcendent at the same time is a key element of the three body theory which challenges us to attain that non-dual state of non-abiding nirvana. This means that, for Ratnākarāśānti, to attempt to logically analyze and construct a coherent system of the dhamakaya is to miss the point of the teaching, and to replace it with just another mental construction.[99]

In Tibet the debate was picked up by later Tibetan thinkers. For example, the Gelug founder Tsongkhapa followed the four body model of Haribhadra, while the Sakya scholar Gorampa supports the basic three body model of Vimuktisena.[91] In Tibetan Buddhism, one common meaning of the fourth body, the svābhāvikakāya (when understood as a different concept than dharmakāya), is that it is refers to the inseparability and identity of all three kāyas.

A four body theory also appears in some East Asian sources, for example, Ching-Ying Huiyuan argued that the Laṅkāvatāra Sūtra taught four bodies: Suchness-Buddha, Wisdom Buddha, Merit Buddha, and Incarnation Buddha.[20]

Interpretation in Buddhist traditions

[edit]Various Buddhist traditions have different ideas about the Buddha body theory.[100][101]

East Asian Buddhism

[edit]

Chinese Buddhism adopts the basic three bodies concept of Indian Mahayana Buddhism, with the Nirmaṇakāya mostly referring to Shakyamuni, the Sambhogakāya being associated with Buddhas like Amitābha and the Dharmakāya understood in different ways depending on the tradition. For example, the Dharmakāya in the Chinese Esoteric Buddhist and Huayan traditions is often understood through the cosmic body of Mahavairocana, which consists of the whole cosmos and also is the basis for all reality, the ultimate principle (li, 理), equivalent to the One Mind taught in the Awakening of Faith.[102][103]

Furthermore, the Huayan school, while affirming the trikaya doctrine, also teaches a different Buddha body theory as well, the theory of ten Buddha bodies. This theory is drawn from the Avatamsaka sutra and states that Buddhas have the following ten bodies: the All-Beings Body, the Lands Body, the Karma Body, the Śrāvakas Body, the Pratyekabuddha Body, the Bodhisattvas Body, the Tathāgatas Body, the Wisdom Body, the Dharma Body, and the Space Body.[104] According to the patriarch Fazang, the ten bodies encompass all dharmas in the "three realms", i.e. the entire universe.[105][106]

In the Tiantai school meanwhile, the three bodies is understood through the central doctrine of the three truths and their interpenetration. Tiantai patriarch Zhiyi argues that all three bodies are ultimately ontologically equal, none of them are ontologically prior or more fundamental than the others.[107] Thus, in Tiantai, there is no hierarchy among the three bodies, just like there is no hierarchy or duality among the threefold truth. All three bodies are ultimately interpenetrated and non-dual.[107]

In the esoteric Buddhist traditions (like Tendai and Shingon), the three bodies are associated with the three mysteries, sanmitsu (三密) of body, speech and mind of the Dharmakaya Buddha, who is associated with Mahavairocana Buddha. According to the Indian Mantrayana patriarch Śubhākarasiṃha: "the three modes of action are simply the three secrets, and the three secrets are simply the three modes of action. The three [Buddha] bodies are simply the wisdom of tathāgata Mahavairocana."[108]

A unique view of the esoteric schools is that the Dharmakaya preaches the Dharma directly, and that this direct teaching is the esoteric Buddhist teachings. This is explained by the Japanese Shingon founder Kukai in his Difference between exoteric and esoteric (Benkenmitsu nikyoron) which says that mikkyo is taught by the cosmic embodiment (hosshin) Buddha. Traditionally, Indian Mahayana held that since the Dharmakaya is formless, wordless, and thoughtless, it does not teach.

According to Schloegl, in the Record of Linji (which is a Chan compilation of the teachings of Linji), the Three Bodies of the Buddha are not taken as absolute or as something outside oneself. Instead they are seen as "merely names or props" which are ultimately just "mental configurations", the play of mind.[109][a] The Record of Linji further advises that the triple body is just one's own heart-mind:

Do you wish to be not different from the Buddhas and patriarchs? Then just do not look for anything outside. The pure light of your own heart [i.e., 心, mind] at this instant is the Dharmakaya Buddha in your own house. The non-differentiating light of your heart at this instant is the Sambhogakaya Buddha in your own house. The non-discriminating light of your own heart at this instant is the Nirmanakaya Buddha in your own house. This trinity of the Buddha's body is none other than here before your eyes, listening to my expounding the Dharma.[111]

Tibetan Buddhism

[edit]

Three Vajras

[edit]The Three Vajras, namely "body, speech and mind", are a formulation within Vajrayana Buddhism and Bon that hold the full experience of the śūnyatā "emptiness" of Buddha-nature, void of all qualities (Wylie: yon tan) and marks[112] (Wylie: mtshan dpe) and establish a sound experiential key upon the continuum of the path to enlightenment. The Three Vajras correspond to the trikaya and therefore also have correspondences to the Three Roots and other refuge formulas of Tibetan Buddhism. The Three Vajras are viewed in twilight language as a form of the Three Jewels, which imply purity of action, speech and thought.

The Three Vajras are often mentioned in Vajrayana discourse, particularly in relation to samaya, the vows undertaken between a practitioner and their guru during empowerment. The term is also used during Anuttarayoga Tantra practice.

The Three Vajras are often employed in tantric sādhanā at various stages during the visualization of the generation stage, refuge tree, guru yoga and iṣṭadevatā processes. The concept of the Three Vajras serves in the twilight language to convey polysemic meanings,[citation needed] aiding the practitioner to conflate and unify the mindstream of the iṣṭadevatā, the guru and the sādhaka in order for the practitioner to experience their own Buddha-nature.

Speaking for the Nyingma tradition, Tulku Urgyen Rinpoche perceives an identity and relationship between Buddha-nature, dharmadhatu, dharmakāya, rigpa and the Three Vajras:

Dharmadhātu is adorned with Dharmakāya, which is endowed with Dharmadhātu Wisdom. This is a brief but very profound statement, because "Dharmadhātu" also refers to Sugatagarbha or Buddha-Nature. Buddha- Nature is all-encompassing... This Buddha-Nature is present just as the shining sun is present in the sky. It is indivisible from the Three Vajras [i.e. the Buddha's Body, Speech and Mind] of the awakened state, which do not perish or change.[113]

Robert Beer (2003: p. 186) states:

The trinity of body, speech, and mind are known as the three gates, three receptacles or three vajras, and correspond to the western religious concept of righteous thought (mind), word (speech), and deed (body). The three vajras also correspond to the three kayas, with the aspect of body located at the crown (nirmanakaya), the aspect of speech at the throat (sambhogakaya), and the aspect of mind at the heart (dharmakaya)."[114]

The bīja corresponding to the Three Vajras are: a white om (enlightened body), a red ah (enlightened speech) and a blue hum (enlightened mind).[115]

Simmer-Brown (2001: p. 334) asserts that:

When informed by tantric views of embodiment, the physical body is understood as a sacred maṇḍala (Wylie: lus kyi dkyil).[116]

This explicates the semiotic rationale for the nomenclature of the somatic discipline called trul khor.

The triple continua of body-voice-mind are intimately related to the Dzogchen doctrine of "sound, light and rays" (Wylie: sgra 'od zer gsum) as a passage of the rgyud bu chung bcu gnyis kyi don bstan pa ('The Teaching on the Meaning of the Twelve Child Tantras') rendered into English by Rossi (1999: p. 65) states (Tibetan provided for probity):

|

|

Barron et al. (1994, 2002: p. 159), renders from Tibetan into English, a terma "pure vision" (Wylie: dag snang) of Sri Singha by Dudjom Lingpa that describes the Dzogchen state of 'formal meditative equipoise' (Tibetan: nyam-par zhag-pa) which is the indivisible fulfillment of vipaśyanā and śamatha, Sri Singha states:

Just as water, which exists in a naturally free-flowing state, freezes into ice under the influence of a cold wind, so the ground of being exists in a naturally free state, with the entire spectrum of samsara established solely by the influence of perceiving in terms of identity.

Understanding this fundamental nature, you give up the three kinds of physical activity--good, bad, and neutral--and sit like a corpse in a charnal ground, with nothing needing to be done. You likewise give up the three kinds of verbal activity, remaining like a mute, as well as the three kinds of mental activity, resting without contrivance like the autumn sky free of the three polluting conditions.[118]

Buddha-bodies

[edit]Vajrayana sometimes refers to a fourth body called the svābhāvikakāya (Tibetan: ངོ་བོ་ཉིད་ཀྱི་སྐུ, Wylie: ngo bo nyid kyi sku) "essential body",[119][120][121] and to a fifth body, called the mahāsūkhakāya (Wylie: bde ba chen po'i sku, "great bliss body").[122] The svābhāvikakāya is simply the unity or non-separateness of the three kayas.[123] The term is also known in Gelug teachings, where it is one of the assumed two aspects of the dharmakāya: svābhāvikakāya "essence body" and jñānakāya "body of wisdom".[124]

In dzogchen teachings, "dharmakaya" means the buddha-nature's absence of self-nature, that is, its emptiness of a conceptualizable essence, its cognizance or clarity is the sambhogakaya, and the fact that its capacity is 'suffused with self-existing awareness' is the nirmanakaya.[125]

The interpretation in Mahamudra is similar: When the mahamudra practices come to fruition, one sees that the mind and all phenomena are fundamentally empty of any identity; this emptiness is called dharmakāya. One perceives that the essence of mind is empty, but that it also has a potentiality that takes the form of luminosity.[clarification needed] In Mahamudra thought, Sambhogakāya is understood to be this luminosity. Nirmanakāya is understood to be the powerful force with which the potentiality affects living beings.[126]

In the view of Anuyoga, the Mind Stream (Sanskrit: citta santana) is the 'continuity' (Sanskrit: santana; Wylie: rgyud) that links the Trikaya.[127] The Trikāya, as a triune, is symbolised by the Gankyil.

Dakinis

[edit]A ḍākinī (Tibetan: མཁའ་འགྲོ་[མ་], Wylie: mkha' 'gro [ma] khandro[ma]) is a tantric deity described as a female embodiment of enlightened energy. The Sanskrit term is likely related to the term for drumming, while the Tibetan term means "sky goer" and may have originated in the Sanskrit khecara, a term from the Cakrasaṃvara Tantra.[128]

Ḍākinīs can also be classified according to the trikāya theory. The dharmakāya ḍākinī, which is Samantabhadrī, represents the dharmadhatu where all phenomena appear. The sambhogakāya ḍākinī are the yidams used as meditational deities for tantric practice. The nirmanakaya ḍākinīs are human women born with special potentialities; these are realized yogini, the consorts of the gurus, or even all women in general as they may be classified into the families of the Five Tathagatas.[129]

In Daoism

[edit]Chinese Daoist literature borrowed the concept from Buddhist sources and modified it to suit Daoist philosophy.[130] This trend began with the works of the Twofold Mystery school (Chongxuan Dao). The literature of this school, such as the Tao-chiao i-shu (Pivotal Meaning of the Taoist Teaching) by Meng An-p’ai, is heavily influenced by Buddhist terminology.[130]

According to Sharf, the Tao-chiao i-shu presents a Daoist triple body theory (sanshen 三身) based on an ultimate “law-body” (fa-shen, 法身, the same Chinese characters used in Buddhism for Dharmakaya), which is a "fundamental principle on which all is “modeled” (fa); it is also used to refer to the Taoist deity the Heavenly Venerable (t’ien-tsun)."[130] This law body produces two further bodies: the fundamental-body (本身, pen-shen), which produces all the "ten thousand things" (in the universe), and the trace-body (跡身, chi-shen).[130]

Comparison with other divine triune concepts

[edit]The three body theory has been compared to other concepts in other religions which are triune in nature or rely on triple deities. Gadjin Nagao notes that some (like A. K. Coomaraswamy) have compared trikaya to the Christian doctrine of the Trinity, but that a closer comparison is that between a formless (nirguna) Brahman, Ishvara and its avatars in mature Hindu theology.[20] A major difference with these other systems however, is that Buddhism rejects the concept of a Creator Deity or Ishvara (supreme lord) who is the controller of karma and reincarnation.[20]

Regarding the Christian concept of the Trinity, Buddhism rejects the idea that there can only be one divine incarnation (i.e. one incarnation of "the Son"). Indeed, in Buddhism, there are an immeasurable number of manifestations (nirmanakayas) throughout the universe. So this is a major difference between the Trinity and the Trikaya.[20] Buddhism also sees the Dharmakaya as being non-dual with the whole cosmos, while Christian theology generally affirms a creator-creature distinction in which the created world (created ex nihilo) and its creatures are generally seen as ontologically distinct from God (and dependent on God for their being). Furthermore, Mahayana's classic docetism regarding the nirmanakaya would put it in conflict with orthodox Christian views.

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ Lin-ji yu-lu: "The scholars of the Sutras and Treatises take the Three Bodies as absolute. As I see it, this is not so. These Three Bodies are merely names, or props. An old master said: "The (Buddha's) Bodies are set up with reference to meaning; the (Buddha) Fields are distinguished with reference to substance." However, understood clearly, the Dharma Nature Bodies and the Dharma Nature Fields are only mental configurations."[110]

References

[edit]- ^ de la Vallée Poussin, Louis. (1906). "XXXI. Studies in Buddhist Dogma. The Three Bodies of a Buddha (Trikāya)." Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain & Ireland, 38(4), 943–977. doi:10.1017/S0035869X0003522X

- ^ a b c d Snelling 1987, p. 100.

- ^ a b c Makransky 1997, p. 86-88.

- ^ Jülch, Thomas (2021). Zhipan’s Account of the History of Buddhism in China. Brill publications. ISBN 9789004447486.

- ^ a b c Han, Jaehee (2021). "The Gaganagañjaparipṛcchā and the Sky as a Symbol of Mahāyāna Doctrines and Aspirations". Religions. 12 (10): 849. doi:10.3390/rel12100849. hdl:11250/3024345.

- ^ a b Trungpa, C. The Collected Works of Chogyam Trungpa: Volume Four, Dawn of tantra, p. 366

- ^ Williams 2009, p. 174.

- ^ Makransky 1997, p. 5.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j "The Sūtra of the Sublime Golden Light (1) / 84000 Reading Room". 84000 Translating The Words of The Buddha. Retrieved 2024-09-29.

- ^ Makransky 1997, p. 88.

- ^ a b c Makransky 1997, p. 51.

- ^ a b Makransky 1997, p. 92.

- ^ Makransky 1997, p. 93.

- ^ a b c "The Sūtra on the Three Bodies / 84000 Reading Room". 84000 Translating The Words of The Buddha. Retrieved 2024-09-30.

- ^ Robert E. Buswell and Donald S. Lopez (2014). The Princeton Dictionary of Buddhism, pp. 1, 24. Published by Princeton University Press

- ^ "The Bija/Seed Syllable A in Siddham, Tibetan, Lantsa scripts - meaning and use in Buddhism". www.visiblemantra.org. Archived from the original on 2021-12-23. Retrieved 2022-07-12.

- ^ Strand, Clark (2011-05-12). "Green Koans 45: The Perfection of Wisdom in One Letter". Tricycle: The Buddhist Review. Archived from the original on 2020-11-24. Retrieved 2022-07-12.

- ^ a b c Griffin 2018, p. 278.

- ^ Williams 2009, p. 178-179.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o Gadjin, Nagao, and Hirano Umeyo. “On the Theory of Buddha-Body (Buddha-Kāya).” The Eastern Buddhist, vol. 6, no. 1, 1973, pp. 25–53. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/44361355. Accessed 29 Sept. 2024.

- ^ a b c Williams 2009, p. 175.

- ^ a b c d Williams 2009, p. 179.

- ^ Williams 2009, p. 185.

- ^ a b c "A Buddhist Bible: The Lankavatara Sutra: Chapter XII. Tathagatahood Which Is Noble Wisdom". sacred-texts.com. Retrieved 2024-09-30.

- ^ a b c Williams 2009, p. 178.

- ^ Makransky 1997, p. 90.

- ^ a b Makransky 1997, p. 91.

- ^ a b c d Williams 2009, p. 180.

- ^ Makransky 1997, p. 93-94.

- ^ Makransky 1997, p. 89.

- ^ "Mahāparinirvāṇasūtra (Buddha-nature, Tsadra Foundation)". buddhanature.tsadra.org. Retrieved 2023-09-28.

- ^ a b Lodrö Sangpo, G. et al. (trans.) (2017). Vijñapti-mātratā-siddhi: A Commentary (Cheng Weishi Lun) on Vasubandhu's Triṃśikā by Xuanzang, p. 1119-1128. (The Collected Works of Louis de La Vallée Poussin; Vol. 1-2). Motilal Banarsidass Publishing House.

- ^ Lodrö Sangpo, G. et al. (trans.) (2017). Vijñapti-mātratā-siddhi: A Commentary (Cheng Weishi Lun) on Vasubandhu's Triṃśikā by Xuanzang, p. 1128-1131. (The Collected Works of Louis de La Vallée Poussin; Vol. 1-2). Motilal Banarsidass Publishing House.

- ^ Guang Xing (2005), pp. 133-134

- ^ Makransky 1997, p. 105.

- ^ Gadjin, Nagao, and Hirano Umeyo. “On the Theory of Buddha-Body (Buddha-Kāya).” The Eastern Buddhist, vol. 6, no. 1, 1973, pp. 25–53. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/44361355. Accessed 29 Sept. 2024.

- ^ Makransky 1997, p. 106.

- ^ Williams 2009, p. 183-84.

- ^ a b c d Williams 2009, p. 181.

- ^ Mattice, S.A. (2021). Exploring the Heart Sutra. Lexington Books. p. 128. ISBN 978-1-4985-9941-2. Retrieved 2023-08-23.

- ^ Lodrö Sangpo, G. et al. (trans.) (2017). Vijñapti-mātratā-siddhi: A Commentary (Cheng Weishi Lun) on Vasubandhu's Triṃśikā by Xuanzang, pp. 1120-1124. (The Collected Works of Louis de La Vallée Poussin; Vol. 1-2). Motilal Banarsidass Publishing House.

- ^ Lodrö Sangpo, G. et al. (trans.) (2017). Vijñapti-mātratā-siddhi: A Commentary (Cheng Weishi Lun) on Vasubandhu's Triṃśikā by Xuanzang, pp. 1122-1127. (The Collected Works of Louis de La Vallée Poussin; Vol. 1-2). Motilal Banarsidass Publishing House.

- ^ Lodrö Sangpo, G. et al. (trans.) (2017). Vijñapti-mātratā-siddhi: A Commentary (Cheng Weishi Lun) on Vasubandhu's Triṃśikā by Xuanzang, pp. 1129. (The Collected Works of Louis de La Vallée Poussin; Vol. 1-2). Motilal Banarsidass Publishing House.

- ^ a b Lodrö Sangpo, G. et al. (trans.) (2017). Vijñapti-mātratā-siddhi: A Commentary (Cheng Weishi Lun) on Vasubandhu's Triṃśikā by Xuanzang, p. 1121 (The Collected Works of Louis de La Vallée Poussin; Vol. 1-2). Motilal Banarsidass Publishing House.

- ^ Lodrö Sangpo, G. et al. (trans.) (2017). Vijñapti-mātratā-siddhi: A Commentary (Cheng Weishi Lun) on Vasubandhu's Triṃśikā by Xuanzang, p. 1125-1131. (The Collected Works of Louis de La Vallée Poussin; Vol. 1-2). Motilal Banarsidass Publishing House.

- ^ Gadjin, Nagao, and Hirano Umeyo. “On the Theory of Buddha-Body (Buddha-Kāya).” The Eastern Buddhist, vol. 6, no. 1, 1973, pp. 25–53. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/44361355. Accessed 29 Sept. 2024.

- ^ Williams 2009, p. 181-82.

- ^ Makransky 1997, p. 121.

- ^ Williams 2009, p. 173, 181.

- ^ Lodrö Sangpo, G. et al. (trans.) (2017). Vijñapti-mātratā-siddhi: A Commentary (Cheng Weishi Lun) on Vasubandhu's Triṃśikā by Xuanzang, p. 1125 (The Collected Works of Louis de La Vallée Poussin; Vol. 1-2). Motilal Banarsidass Publishing House.

- ^ Lodrö Sangpo, G. et al. (trans.) (2017). Vijñapti-mātratā-siddhi: A Commentary (Cheng Weishi Lun) on Vasubandhu's Triṃśikā by Xuanzang, p. 1131 (The Collected Works of Louis de La Vallée Poussin; Vol. 1-2). Motilal Banarsidass Publishing House.

- ^ Williams 2009, p. 177.

- ^ a b c Williams 2009, p. 176.

- ^ Xing (2005), pp. 69-73

- ^ Makransky 1997, p. 24.

- ^ Makransky 1997, p. 25-26.

- ^ Makransky 1997, p. 25.

- ^ a b Makransky 1997, p. 26.

- ^ Xing (2005), p. 74.

- ^ Xing (2005), p. 73.

- ^ Makransky 1997, p. 31.

- ^ Makransky 1997, p. 33-34.

- ^ Xing (2005), pp. 77-79.

- ^ Makransky 1997, p. 36-37.

- ^ Guang Xing (2005), p. 81.

- ^ a b Williams 2009, p. 177-78.

- ^ Makransky 1997, p. 30.

- ^ a b Guang Xing (2005), p. 85.

- ^ Guang Xing (2005), p. 83.

- ^ Guang Xing (2005), p. 84.

- ^ Guang Xing (2005), p. 88.

- ^ Guang Xing (2005), p. 92.

- ^ Guang Xing (2005), p. 89.

- ^ Guang Xing (2005), p. 136.

- ^ a b Guang Xing (2005), pp. 138-139.

- ^ Guang Xing (2005), p. 141.

- ^ a b Guang Xing (2005), p. 102.

- ^ Guang Xing (2005), pp. 132-33.

- ^ Snelling 1987, p. 126.

- ^ Gadjin, Nagao, and Hirano Umeyo. “On the Theory of Buddha-Body (Buddha-Kāya).” The Eastern Buddhist, vol. 6, no. 1, 1973, pp. 25–53. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/44361355. Accessed 29 Sept. 2024.

- ^ "The Sūtra of the Sublime Golden Light (1) / 84000 Reading Room". 84000 Translating The Words of The Buddha. Retrieved 2024-09-29.

- ^ Makransky 1997, p. 41.

- ^ Makransky 1997, p. 43-44.

- ^ Makransky 1997, p. 62.

- ^ a b c Makransky 1997, p. 51, 60-61.

- ^ Makransky 1997, p. 63.

- ^ Makransky 1997, p. 61-62.

- ^ Makransky 1997, p. 56.

- ^ Makransky 1997, p. 59.

- ^ Makransky 1997, p. 3.

- ^ a b c d Makransky 1997, pp. 15–18, 115

- ^ a b Makransky 1997, p. 6.

- ^ Makransky 1997, p. 10, 39.

- ^ Makransky 1997, p. 10.

- ^ Makransky 1997, p. 13.

- ^ Makransky 1997, p. 40.

- ^ Makransky 1997, p. 14.

- ^ Makransky 1997, p. 14-15.

- ^ a b Makransky 1997, p. 15-16.

- ^ 佛三身觀之研究-以漢譯經論為主要研究對象 [dead link]

- ^ 佛陀的三身觀

- ^ Xing, Guang (2004-11-10). The Concept of the Buddha: Its Evolution from Early Buddhism to the Trikaya Theory. London: Routledge. doi:10.4324/9780203413104. ISBN 978-0-203-41310-4.

- ^ Habito, Ruben L. F. (1986). "The Trikāya Doctrine in Buddhism". Buddhist-Christian Studies. 6: 53–62. doi:10.2307/1390131. ISSN 0882-0945. JSTOR 1390131.

- ^ Lin, Weiyu (2021). Exegesis-philosophy interplay : introduction to Fazang's (643-712) commentary on the Huayan jing (60 juans) [Skt. Avataṃsaka Sūtra; Flower garland sūtra] — the Huayan jing tanxuan ji [record of investigating the mystery of the Huayan jing]. p. 33. Vancouver: University of British Columbia Library.

- ^ Lin, Weiyu (2021). Exegesis-philosophy interplay : introduction to Fazang's (643-712) commentary on the Huayan jing (60 juans) [Skt. Avataṃsaka Sūtra; Flower garland sūtra] — the Huayan jing tanxuan ji [record of investigating the mystery of the Huayan jing]. p. 34. Vancouver: University of British Columbia Library.

- ^ Hamar, Imre. The Manifestation of the Absolute in the Phenomenal World: Nature Origination in Huayan Exegesis.[permanent dead link] In: Bulletin de l'École Française d'Extrême-Orient. Tome 94, 2007. pp. 229-250; doi:10.3406/befeo.2007.6070

- ^ a b Kyohei Mikawa. The Cunning of Buddhahood, An Omnitelic Reconception of Teleology in Tiantai Buddhist Thought, p. 192, 2023, Chicago, Illinois.

- ^ Orzech, Charles D; Sorensen, Henrik Hjort; Payne, Richard Karl (2011). Esoteric Buddhism and the tantras in East Asia, p. 84. Leiden. Boston: Brill. doi:10.1163/ej.9789004184916.i-1200. ISBN 978-90-04-20401-0. OCLC 731667667.

- ^ Schloegl 1976, p. 19.

- ^ Schloegl 1976, p. 21.

- ^ Schloegl 1976, p. 18.

- ^ '32 major marks' (Sanskrit: dvātriṃśanmahāpuruṣalakṣaṇa), and the '80 minor marks' (Sanskrit: aśītyanuvyañjana) of a superior being, refer: Physical characteristics of the Buddha.

- ^ As It Is, Tulku Urgyen Rinpoche, Rangjung Yeshe Books, Hong Kong, 1999, p. 32

- ^ Beer, Robert (2003). The Handbook of Tibetan Buddhist Symbols. Serindia Publications. ISBN 1-932476-03-2 Source: [1] (accessed: December 7, 2007)

- ^ Rinpoche, Pabongka (1997). Liberation in the Palm of Your Hand: A Concise Discourse on the Path to Enlightenment. Wisdom Books. p. 196.

- ^ Simmer-Brown, Judith (2001). Dakini's Warm Breath: the Feminine Principle in Tibetan Buddhism. Boston, USA: Shambhala. ISBN 1-57062-720-7 (alk. paper). p.334

- ^ a b Rossi, Donatella (1999). The philosophical view of the great perfection in the Tibetan Bon religion. Ithaca, NY: Snow Lion Publications. p. 65. ISBN 1-55939-129-4.

- ^ Lingpa, Dudjom; Tulku, Chagdud; Norbu, Padma Drimed; Barron, Richard (Lama Chökyi Nyima, translator); Fairclough, Susanne (translator) (1994, 2002 revised). Buddhahood without meditation: a visionary account known as 'Refining one's perception' (Nang-jang) (English; Tibetan: ran bźin rdzogs pa chen po'i ranźal mnon du byed pa'i gdams pa zab gsan sñin po). Revised Edition. Junction City, CA, USA: Padma Publishing. ISBN 1-881847-33-0, p.159

- ^ remarks on Svabhavikakaya by khandro.net

- ^ In the book Embodiment of Buddhahood Chapter 4 the subject is: Embodiment of Buddhahood in its Own Realization: Yogacara Svabhavikakaya as Projection of Praxis and Gnoseology.

- ^ explanation of meaning

- ^ Tsangnyön Heruka (1995). The life of Marpa the translator : seeing accomplishes all. Boston: Shambhala. p. 229. ISBN 978-1570620874.

- ^ khandro.net citing H.E. Tai Situpa

- ^ Williams 2009.

- ^ Reginald Ray, Secret of the Vajra World. Shambhala 2001, page 315.

- ^ Reginald Ray, Secret of the Vajra World. Shambhala 2001, pages 284-285.

- ^ Welwood, John (2000). The Play of the Mind: Form, Emptiness, and Beyond, accessed January 13, 2007

- ^ Buswell, Robert Jr; Lopez, Donald S. Jr., eds. (2013). Princeton Dictionary of Buddhism. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. ISBN 9780691157863.

- ^ Cf. Capriles, Elías (2003/2007). Buddhism and Dzogchen [2]', and Capriles, Elías (2006/2007). Beyond Being, Beyond Mind, Beyond History, vol. I, Beyond Being[3]

- ^ a b c d Sharf, Robert H. Coming to Terms with Chinese Buddhism: A Reading of the Treasure Store Treatise. p. 69. University of Hawaii Press, Nov 30, 2005

Sources

[edit]- Griffin, David Ray (2018), Reenchantment without Supernaturalism: A Process Philosophy of Religion, Cornell University Press

- Makransky, John J. (1997), Buddhahood Embodied: Sources of Controversy in India and Tibet, State University of New York Press, ISBN 0-7914-3432-X

- Schloegl, Irmgard (1976), The Zen Teaching of Rinzai (PDF), Shambhala Publications, Inc., ISBN 0-87773-087-3

- Snelling, John (1987), The Buddhist handbook. A Complete Guide to Buddhist Teaching and Practice, London: Century Paperbacks

- Xing, Guang (2005). The Concept of the Buddha: Its Evolution from Early Buddhism to the Trikāya Theory. Psychology Press. ISBN 978-0-415-33344-3.

Further reading

[edit]- Radich, Michael (2007). Problems and Opportunities in the Study of the Bodies of the Buddha, New Zealand Journal of Asian Studies 9 (1), 46-69

- Radich, Michael (2010). Embodiments of the Buddha in Sarvâstivāda Doctrine: With Special Reference to the Mahavibhāṣā. Annual Report of the International Research Institute for Advanced Buddhology 13, 121-172

- Snellgrove, David (1987). Indo-Tibetan Buddhism, Vol. 1. Boston, Massachusetts: Shambhala Publications, Inc. ISBN 0-87773-311-2.

- Snellgrove, David (1987). Indo-Tibetan Buddhism, Vol. 2. Boston, Massachusetts: Shambhala Publications, Inc. ISBN 0-87773-379-1.

- Walsh, Maurice (1995). The Long Discourses of the Buddha: A Translation of the Dīgha Nikāya. Boston: Wisdom Publications. ISBN 0-86171-103-3.