Ticagrelor

| |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Trade names | Brilinta, Brilique, others |

| Other names | AZD-6140 |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph |

| MedlinePlus | a611050 |

| License data |

|

| Pregnancy category |

|

| Routes of administration | By mouth |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status | |

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Bioavailability | 36% |

| Protein binding | >99.7% |

| Metabolism | Liver (CYP3A4) |

| Elimination half-life | 7 hrs (ticagrelor), 8.5 hrs (active metabolite AR-C124910XX) |

| Excretion | Bile duct |

| Identifiers | |

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| IUPHAR/BPS | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| KEGG | |

| ChEMBL | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.114.746 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

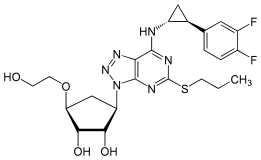

| Formula | C23H28F2N6O4S |

| Molar mass | 522.57 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| |

| |

| | |

Ticagrelor, sold under the brand name Brilinta among others, is a medication used for the prevention of stroke, heart attack and other events in people with acute coronary syndrome, meaning problems with blood supply in the coronary arteries. It acts as a platelet aggregation inhibitor by antagonising the P2Y12 receptor.[7] The drug is produced by AstraZeneca.

The most common side effects include dyspnea (difficulty breathing), bleeding and raised uric acid level in the blood.[6]

It was approved for medical use in the European Union in December 2010,[6][8][9] and in the United States in July 2011.[5][10][11] In 2022, it was the 203rd most commonly prescribed medication in the United States, with more than 2 million prescriptions.[12][13]

Medical uses

[edit]In the US, ticagrelor is indicated to reduce the risk of stroke in people with acute ischemic stroke or high-risk transient ischemic attack.[5]

In the EU, ticagrelor, co-administered with acetylsalicylic acid (aspirin), is indicated for the prevention of atherothrombotic events in adults with acute coronary syndromes or a history of myocardial infarction and a high risk of developing an atherothrombotic event; and for the prevention of atherothrombotic events in adults with a history of myocardial infarction and a high risk of developing an atherothrombotic event.[6]

Contraindications

[edit]Contraindications to ticagrelor are active bleeding, increased risk of bradycardia, concomitant therapy of ticagrelor and strong cytochrome P-450 3A (CYP3A4) inhibitors and moderate or severe hepatic impairment due to the risk of increased exposure to ticagrelor.[14][15]

Adverse effects

[edit]The common adverse effects are increased risk of bleeding (which may be severe)[16] and shortness of breath (dyspnoea).[17] Dyspnoea is usually transient and mild-to-moderate in severity, with a higher risk at < 1 month, 1–6 months and >6 months of follow up compared to clopidogrel.[17][18][19][20] Discontinuation of therapy is rare, although some people do not persist or switch therapies.[17][18][19] People who develop tolerable dyspnoea as a side effect of ticagrelor should be reassured to continue therapy, as it does not impact on the drug's cardiovascular benefit and bleeding risk in acute coronary syndrome (ACS).[17] Furthermore, two small subgroup analyses found no associations between ticagrelor and adverse changes in heart and lung function that may induce dyspnoea in stable coronary artery disease (CAD) and people with ACS without heart failure or significant lung disease.[18][21]

Ventricular pauses ≥3 seconds may occur in people with ACS the first week of treatment, but are likely to be mostly asymptomatic and transient, without causing increased clinical bradycardic adverse events.[22] Caution is recommended when using ticagrelor in people with advanced sinoatrial node disease.[23] Allergic skin reactions such as rash and itching have been observed in less than 1% of people taking ticagrelor.[24]

Interactions

[edit]Inhibitors of the liver enzyme CYP3A4, such as ketoconazole and possibly grapefruit juice, increase blood plasma levels of ticagrelor and consequently can lead to bleeding and other adverse effects. Ticagrelor is a weak CYP3A4 inhibitor and can increase the plasma concentration of CYP3A4 substrates[25] Current evidence suggests that use of ticagrelor with statins can increase the risk of adverse effects like myopathy and rhabdomyolysis. However, this evidence is weak, and more research is needed.[25][26] While it appears that the risk is low for most people, caution should be used when the medications are combined.[25][26] This is especially important in elderly patients, and some evidence suggests that extra caution should be used with renally impaired patients as well.[26][25] CYP3A4 inducers, for example rifampicin and possibly St. John's wort, can reduce the effectiveness of ticagrelor. There is no evidence for interactions via CYP2C9.

The drug also inhibits P-glycoprotein (P-gp), leading to increased plasma levels of digoxin, ciclosporin and other P-gp substrates. Levels of ticagrelor and AR-C124910XX (the active metabolite of ticagrelor formed by O-deethylation[27]) are not significantly influenced by P-gp inhibitors.[24]

It is generally recommended to use low-dose aspirin (75-100 mg per day) with ticagrelor when dual antiplatelet therapy (DAPT) is indicated. It has been observed that the use of 325 mg daily aspirin in DAPT increases the risk of bleeding events, without lowering the rate of a major adverse cardiovascular event (MACE) such as cardiovascular death, heart attack, stroke or unplanned revascularisation (restoration of blood flow).[28]

Pharmacology

[edit]Mechanism of action

[edit]Like the thienopyridines prasugrel, clopidogrel and ticlopidine, ticagrelor blocks adenosine diphosphate (ADP) receptors of subtype P2Y12. In contrast to the other antiplatelet drugs, ticagrelor has a binding site different from ADP, making it an allosteric antagonist, and the blockage is reversible.[29] Moreover, the drug does not need hepatic activation, which might work better for people with genetic variants regarding the enzyme CYP2C19 (although it is not certain whether clopidogrel is significantly influenced by such variants).[30][31][32] Ticagrelor was found to result in a lower risk of stroke at 90 days than clopidogrel, which requires metabolic conversion, among Han Chinese CYP2C19 loss-of-function carriers with minor ischemic stroke or TIA.[33]

Pharmacokinetics

[edit]Ticagrelor is absorbed quickly from the gut, the bioavailability being 36%, and reaches its peak concentration after about 1.5 hours. The main metabolite, AR-C124910XX, is formed quickly via CYP3A4 by de-hydroxyethylation at position 5 of the cyclopentane ring.[27]

Plasma concentrations of ticagrelor are slightly increased (12–23%) in elderly people, women, people of Asian ethnicity, and people with mild hepatic impairment. They are decreased in people that self-identified as 'black' and those with severe renal impairment. These differences are not considered clinically relevant. In Japanese people, concentrations are 40% higher than in Caucasians, or 20% after body weight correction. The drug has not been tested in people with severe hepatic impairment.[24][34]

Consistently with its reversible mode of action, ticagrelor is known to act faster and shorter than clopidogrel.[35] This means it has to be taken twice instead of once a day which is a disadvantage in respect of compliance, but its effects are more quickly reversible which can be useful before surgery or if side effects occur.[24][36]

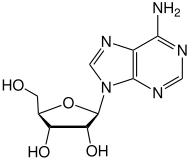

Chemistry

[edit]Ticagrelor is a nucleoside analogue: the cyclopentane ring is similar to the sugar ribose, and the nitrogen rich aromatic ring system resembles the nucleobase purine, giving the molecule an overall similarity to adenosine. The substance has low solubility and low permeability under the Biopharmaceutics Classification System.[8]

|

|

Research

[edit]Comparison with related drugs

[edit]With clopidogrel

[edit]The PLATO trial concluded superiority of ticagrelor compared to clopidogrel in reducing the rate of death from vascular causes, MI, and stroke in people presenting with acute coronary syndromes.[14] A post-hoc subgroup analysis of the PLATO trial suggested a reduction in total mortality with ticagrelor compared to clopidogrel in people with non-ST elevation acute coronary syndrome.[37] However, this finding should only be considered exploratory as it was not a primary endpoint of the PLATO trial.[14] Ticagrelor, as monotherapy, dual antiplatelet therapy (DAPT), and in comparison to clopidogrel, is associated with decreased all-cause mortality. When in comparison to clopidogrel, there is evidence for increased risk of bleeding.[38]

The PLATO trial[39] found that ticagrelor use, in conjunction with low-dose aspirin (where tolerated), had better all-cause mortality rates than the same treatment plan with clopidogrel (4.5% vs. 5.9%) in treating people with acute coronary syndrome. People given ticagrelor were less likely to die from vascular causes, heart attack, or stroke, regardless of whether the treatment plan was invasive.

There is some conjecture in the safety and efficacy of ticagrelor within the Asian population, despite significant thrombotic benefits.[37] A meta-analysis of observational studies in several Asian countries proposed that ticagrelor did not increase the risk of considerable bleeding events in Asian individuals.[40] There is evidence to suggest that East Asian individuals are at a higher risk of bleeding events when using ticagrelor.[41][42][43] The guidelines recommend that people of East Asian origin exercise caution and that treatment continuation after six months be based on net-clinical benefit.[44]

With prasugrel

[edit]In 2019, the ISAR-REACT 5 trial comparing ticagrelor and prasugrel in participants with acute coronary syndrome showed that people with acute coronary disease receiving prasugrel had lower incidence of death, myocardial infarction, or stroke compared to those who received ticagrelor.[45]

A 2019 study showed antibacterial activity against antibiotic-resistant Gram-positive bacteria including methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus and vancomycin-resistant enterococcus.[46] This study used concentrations of ticagrelor for bactericidal activity that far exceeded those achieved by standard post acute coronary syndrome doses.[46] Research indicates that ticagrelor may help reduce the risk of infections, such as pneumonia and sepsis.[47][48]

References

[edit]- ^ "Updates to the Prescribing Medicines in Pregnancy database". Therapeutic Goods Administration (TGA). 12 May 2022. Retrieved 13 May 2022.

- ^ "FDA-sourced list of all drugs with black box warnings (Use Download Full Results and View Query links.)". nctr-crs.fda.gov. FDA. Retrieved 22 October 2023.

- ^ "Ticalor; Blooms The Chemist Ticagrelor; Apo-Ticagrelor; Ticagrelor Arx (Accelagen Pty Ltd)". Therapeutic Goods Administration (TGA). 11 November 2022. Retrieved 9 April 2023.

- ^ "Product monograph brand safety updates". Health Canada. February 2024. Retrieved 24 March 2024.

- ^ a b c "Brilinta- ticagrelor tablet". DailyMed. 10 August 2021. Retrieved 19 May 2022.

- ^ a b c d "Brilique EPAR". European Medicines Agency. 17 September 2018. Retrieved 18 May 2022. Text was copied from this source which is copyright European Medicines Agency. Reproduction is authorized provided the source is acknowledged.

- ^ Jacobson KA, Boeynaems JM (July 2010). "P2Y nucleotide receptors: promise of therapeutic applications". Drug Discovery Today. 15 (13–14): 570–578. doi:10.1016/j.drudis.2010.05.011. PMC 2920619. PMID 20594935.

- ^ a b "Assessment Report for Brilique" (PDF). European Medicines Agency. January 2011. Archived from the original (PDF) on 17 May 2018. Retrieved 3 February 2011.

- ^ "European Public Assessment Report Possia". Archived from the original on 12 June 2018. Retrieved 24 January 2011.

- ^ "FDA approves blood-thinning drug Brilinta to treat acute coronary syndromes" (Press release). U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). 20 July 2011. Archived from the original on 12 January 2017.

- ^ "Drug Approval Package: Brilinta (ticagrelor) NDA #022433". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). 22 August 2011. Retrieved 22 May 2021.

- ^ "The Top 300 of 2022". ClinCalc. Archived from the original on 30 August 2024. Retrieved 30 August 2024.

- ^ "Ticagrelor Drug Usage Statistics, United States, 2013 - 2022". ClinCalc. Retrieved 30 August 2024.

- ^ a b c Wallentin L, Becker RC, Budaj A, Cannon CP, Emanuelsson H, Held C, et al. (September 2009). "Ticagrelor versus clopidogrel in patients with acute coronary syndromes". The New England Journal of Medicine. 361 (11): 1045–1057. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa0904327. hdl:2437/95141. PMID 19717846.

- ^ Davis EM, Knezevich JT, Teply RM (April 2013). "Advances in antiplatelet technologies to improve cardiovascular disease morbidity and mortality: a review of ticagrelor". Clinical Pharmacology. 5: 67–83. doi:10.2147/cpaa.s41859. PMC 3640601. PMID 23650452.

- ^ Becker RC, Bassand JP, Budaj A, Wojdyla DM, James SK, Cornel JH, et al. (December 2011). "Bleeding complications with the P2Y12 receptor antagonists clopidogrel and ticagrelor in the PLATelet inhibition and patient Outcomes (PLATO) trial". European Heart Journal. 32 (23): 2933–2944. doi:10.1093/eurheartj/ehr422. PMID 22090660.

- ^ a b c d Storey RF, Becker RC, Harrington RA, Husted S, James SK, Cools F, et al. (December 2011). "Characterization of dyspnoea in PLATO study patients treated with ticagrelor or clopidogrel and its association with clinical outcomes". European Heart Journal. 32 (23): 2945–2953. doi:10.1093/eurheartj/ehr231. PMID 21804104.

- ^ a b c Storey RF, Bliden KP, Patil SB, Karunakaran A, Ecob R, Butler K, et al. (July 2010). "Incidence of dyspnea and assessment of cardiac and pulmonary function in patients with stable coronary artery disease receiving ticagrelor, clopidogrel, or placebo in the ONSET/OFFSET study". Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 56 (3): 185–193. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2010.01.062. PMID 20620737.

- ^ a b Alexopoulos D, Xanthopoulou I, Perperis A, Goudevenos J, Hamilos M, Sitafidis G, et al. (November 2017). "Dyspnea in patients treated with P2Y12 receptor antagonists: insights from the GReek AntiPlatElet (GRAPE) registry". Platelets. 28 (7): 691–697. doi:10.1080/09537104.2016.1265919. PMID 28150522. S2CID 35647876.

- ^ Zhang N, Xu W, Li O, Zhang B (March 2020). "The risk of dyspnea in patients treated with third-generation P2Y12 inhibitors compared with clopidogrel: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials". BMC Cardiovascular Disorders. 20 (1): 140. doi:10.1186/s12872-020-01419-y. PMC 7079377. PMID 32183711.

- ^ Storey RF, Becker RC, Harrington RA, Husted S, James SK, Cools F, et al. (December 2011). "Pulmonary function in patients with acute coronary syndrome treated with ticagrelor or clopidogrel (from the Platelet Inhibition and Patient Outcomes [PLATO] pulmonary function substudy)". The American Journal of Cardiology. 108 (11): 1542–1546. doi:10.1016/j.amjcard.2011.07.015. PMID 21890085.

- ^ Scirica BM, Cannon CP, Emanuelsson H, Michelson EL, Harrington RA, Husted S, et al. (May 2011). "The incidence of bradyarrhythmias and clinical bradyarrhythmic events in patients with acute coronary syndromes treated with ticagrelor or clopidogrel in the PLATO (Platelet Inhibition and Patient Outcomes) trial: results of the continuous electrocardiographic assessment substudy". Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 57 (19): 1908–1916. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2010.11.056. PMID 21545948.

- ^ 6 [dead link]

- ^ a b c d Haberfeld, H, ed. (2010). Austria-Codex (in German) (2010/2011 ed.). Vienna: Österreichischer Apothekerverlag.

- ^ a b c d Danielak D, Karaźniewicz-Łada M, Główka F (July 2018). "Assessment of the Risk of Rhabdomyolysis and Myopathy During Concomitant Treatment with Ticagrelor and Statins". Drugs. 78 (11): 1105–1112. doi:10.1007/s40265-018-0947-x. PMC 6061431. PMID 30003466.

- ^ a b c Teng R, Mitchell PD, Butler KA (March 2013). "Pharmacokinetic interaction studies of co-administration of ticagrelor and atorvastatin or simvastatin in healthy volunteers". European Journal of Clinical Pharmacology. 69 (3): 477–487. doi:10.1007/s00228-012-1369-4. PMID 22922682. S2CID 17914035.

- ^ a b Teng R, Oliver S, Hayes MA, Butler K (September 2010). "Absorption, distribution, metabolism, and excretion of ticagrelor in healthy subjects". Drug Metabolism and Disposition. 38 (9): 1514–1521. doi:10.1124/dmd.110.032250. PMID 20551239. S2CID 22084793.

- ^ Xian Y, Wang TY, McCoy LA, Effron MB, Henry TD, Bach RG, et al. (July 2015). "Association of Discharge Aspirin Dose With Outcomes After Acute Myocardial Infarction: Insights From the Treatment with ADP Receptor Inhibitors: Longitudinal Assessment of Treatment Patterns and Events after Acute Coronary Syndrome (TRANSLATE-ACS) Study". Circulation. 132 (3): 174–181. doi:10.1161/circulationaha.114.014992. PMID 25995313.

- ^ Birkeland K, Parra D, Rosenstein R (2010). "Antiplatelet therapy in acute coronary syndromes: focus on ticagrelor". Journal of Blood Medicine. 1: 197–219. doi:10.2147/JBM.S9650. PMC 3262315. PMID 22282698.

- ^ Spreitzer H (4 February 2008). "Neue Wirkstoffe - AZD6140". Österreichische Apothekerzeitung (in German) (3/2008): 135.

- ^ Owen RT, Serradell N, Bolos J (2007). "AZD6140". Drugs of the Future. 32 (10): 845–853. doi:10.1358/dof.2007.032.10.1133832.

- ^ [unreliable medical source?] Tantry US, Bliden KP, Wei C, Storey RF, Armstrong M, Butler K, et al. (December 2010). "First analysis of the relation between CYP2C19 genotype and pharmacodynamics in patients treated with ticagrelor versus clopidogrel: the ONSET/OFFSET and RESPOND genotype studies". Circulation: Cardiovascular Genetics. 3 (6): 556–566. doi:10.1161/CIRCGENETICS.110.958561. PMID 21079055.

- ^ Wang Y, Meng X, Wang A, Xie X, Pan Y, Johnston SC, et al. (December 2021). "Ticagrelor versus Clopidogrel in CYP2C19 Loss-of-Function Carriers with Stroke or TIA". The New England Journal of Medicine. 385 (27): 2520–2530. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa2111749. PMID 34708996. S2CID 240072625.

- ^ "Brilique: EPAR – Product Information" (PDF). European Medicines Agency. 16 October 2019.

- ^ Miller R (24 February 2010). "Is there too much excitement for ticagrelor?". TheHeart.org.

- ^ Spreitzer H (17 January 2011). "Neue Wirkstoffe - Elinogrel". Österreichische Apothekerzeitung (in German) (2/2011): 10.

- ^ a b Lindholm D, Varenhorst C, Cannon CP, Harrington RA, Himmelmann A, Maya J, et al. (August 2014). "Ticagrelor vs. clopidogrel in people with non-ST-elevation acute coronary syndrome with or without revascularization: results from the PLATO trial". European Heart Journal. 35 (31): 2083–2093. doi:10.1093/eurheartj/ehu160. PMC 4132637. PMID 24727884.

- ^ Hong SJ, Ahn CM, Kim JS, Kim BK, Ko YG, Choi D, et al. (January 2022). "Effect of ticagrelor monotherapy on mortality after percutaneous coronary intervention: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized trials including 26 143 patients". European Heart Journal - Cardiovascular Pharmacotherapy. 8 (1): 48–55. doi:10.1093/ehjcvp/pvaa119. PMID 33035298.

- ^ [unreliable medical source?] Cannon CP, Harrington RA, James S, Ardissino D, Becker RC, Emanuelsson H, et al. (January 2010). "Comparison of ticagrelor with clopidogrel in patients with a planned invasive strategy for acute coronary syndromes (PLATO): a randomised double-blind study". Lancet. 375 (9711): 283–293. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(09)62191-7. PMID 20079528. S2CID 22469812.

- ^ Galimzhanov AM, Azizov BS (2019). "Ticagrelor for Asian patients with acute coronary syndrome in real-world practice: A systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies". Indian Heart Journal. 71 (1): 15–24. doi:10.1016/j.ihj.2019.01.003. PMC 6477146. PMID 31000178.

- ^ Misumida N, Aoi S, Kim SM, Ziada KM, Abdel-Latif A (September 2018). "Ticagrelor versus clopidogrel in East Asian patients with acute coronary syndrome: Systematic review and meta-analysis". Cardiovascular Revascularization Medicine. 19 (6): 689–694. doi:10.1016/j.carrev.2018.01.009. PMID 29452843. S2CID 3377054.

- ^ Ma Y, Zhong PY, Shang YS, Bai N, Niu Y, Wang ZL (May 2022). "Comparison of Ticagrelor With Clopidogrel in East Asian Patients With Acute Coronary Syndrome: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Clinical Trials". Journal of Cardiovascular Pharmacology. 79 (5): 632–640. doi:10.1097/fjc.0000000000001225. PMID 35091511. S2CID 246388246.

- ^ Wu B, Lin H, Tobe RG, Zhang L, He B (March 2018). "Ticagrelor versus clopidogrel in East-Asian patients with acute coronary syndromes: a meta-analysis of randomized trials". Journal of Comparative Effectiveness Research. 7 (3): 281–291. doi:10.2217/cer-2017-0074. PMID 29094604.

- ^ Tan JW, Chew DP, Abdul Kader MA, Ako J, Bahl VK, Chan M, et al. (February 2021). "2020 Asian Pacific Society of Cardiology Consensus Recommendations on the Use of P2Y12 Receptor Antagonists in the Asia-Pacific Region". European Cardiology. 16: e02. doi:10.15420/ecr.2020.40. PMC 7941380. PMID 33708263.

- ^ Schüpke S, Neumann FJ, Menichelli M, Mayer K, Bernlochner I, Wöhrle J, et al. (October 2019). "Ticagrelor or Prasugrel in Patients with Acute Coronary Syndromes". The New England Journal of Medicine. 381 (16): 1524–1534. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1908973. PMID 31475799. S2CID 201712809.

- ^ a b Lancellotti P, Musumeci L, Jacques N, Servais L, Goffin E, Pirotte B, et al. (June 2019). "Antibacterial Activity of Ticagrelor in Conventional Antiplatelet Dosages Against Antibiotic-Resistant Gram-Positive Bacteria". JAMA Cardiology. 4 (6): 596–599. doi:10.1001/jamacardio.2019.1189. PMC 6506905. PMID 31066863.

- ^ Lupu L, Shepshelovich D, Banai S, Hershkoviz R, Isakov O (September 2020). "Effect of Ticagrelor on Reducing the Risk of Gram-Positive Infections in Patients With Acute Coronary Syndrome". The American Journal of Cardiology. 130: 56–63. doi:10.1016/j.amjcard.2020.06.016. PMID 32680674. S2CID 220631373.

- ^ Butt JH, Fosbøl EL, Gerds TA, Iversen K, Bundgaard H, Bruun NE, et al. (January 2022). "Ticagrelor and the risk of Staphylococcus aureus bacteraemia and other infections". European Heart Journal - Cardiovascular Pharmacotherapy. 8 (1): 13–19. doi:10.1093/ehjcvp/pvaa099. PMID 32750138.