Yogi Berra

| Yogi Berra | |

|---|---|

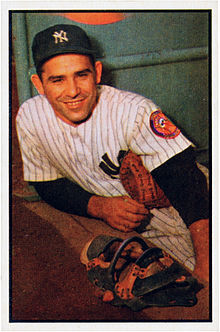

Berra with the New York Yankees in 1953 | |

| Catcher / Manager | |

| Born: May 12, 1925 St. Louis, Missouri | |

| Died: September 22, 2015 (aged 90) West Caldwell, New Jersey | |

Batted: Left Threw: Right | |

| MLB debut | |

| September 22, 1946, for the New York Yankees | |

| Last MLB appearance | |

| May 9, 1965, for the New York Mets | |

| MLB statistics | |

| Batting average | .285 |

| Home runs | 358 |

| Runs batted in | 1,430 |

| Managerial record | 484–444 |

| Winning % | .522 |

| Stats at Baseball Reference | |

| Managerial record at Baseball Reference | |

| Teams | |

| As player

As manager As coach | |

| Career highlights and awards | |

| |

| Member of the National | |

| Induction | 1972 |

| Vote | 85.61% (second ballot) |

Yogi Berra | |

|---|---|

| Allegiance | |

| Service | |

| Years of service | 1943–1945 |

| Rank | Seaman Second Class |

| Unit | Landing Craft Support gunner [1] |

| Battles / wars | World War II: D-Day |

| Awards | |

Lawrence Peter "Yogi" Berra (May 12, 1925 – September 22, 2015) was an American professional baseball catcher, who later took on the roles of manager and coach. He played 19 seasons in Major League Baseball (MLB) (1946–63, 1965), all but the last for the New York Yankees. He was an 18-time All-Star and won 10 World Series championships as a player—more than any other player in MLB history.[2] Berra had a career batting average of .285, while hitting 358 home runs and 1,430 runs batted in. He is one of only five players to win the American League Most Valuable Player Award three times. He is widely regarded as one of the greatest catchers in baseball history,[3] and was elected to the Baseball Hall of Fame in 1972.

Berra was a native of St. Louis and signed with the Yankees in 1943 before serving in the U.S. Navy in World War II. He made his major-league debut at age 21 in 1946 and was a mainstay in the Yankees' lineup during the team's championship years beginning in 1949 and continuing through 1962. Despite his short stature (he was 5' 7" tall), Berra was a power hitter and strong defensive catcher. He caught Don Larsen's perfect game in Game 5 of the 1956 World Series.

Berra played 18 seasons with the Yankees. He spent the next season as their manager, then joined the New York Mets in 1965 as coach (and briefly a player again). Berra remained with the Mets for the next decade, serving the last four years as their manager. He returned to the Yankees in 1976, coaching them for eight seasons and managing for two, before coaching the Houston Astros. He was one of seven managers to lead both American and National League teams to the World Series. Berra appeared as a player, coach or manager in every one of the 13 World Series that New York baseball teams competed in from 1947 through 1981.[2] In all, he appeared in 22 World Series, 13 on the winning side.

The Yankees retired his uniform number 8 in 1972; Bill Dickey also wore number 8, and both catchers had that number retired by the Yankees. The club honored him with a plaque in Monument Park in 1988. Berra was named to the MLB All-Century Team in a vote by fans in 1999. For the remainder of his life, he was closely involved with the Yogi Berra Museum and Learning Center, which he opened on the campus of Montclair State University in 1998.

Berra quit school after the eighth grade.[4] He was known for his malapropisms as well as pithy and paradoxical statements, such as "It ain't over 'til it's over", while speaking to reporters. He once simultaneously denied and confirmed his reputation by stating, "I really didn't say everything I said."[3][5]

Early life

Yogi Berra was born Lorenzo Pietro Berra in a primarily Italian neighborhood of St. Louis called The Hill. His parents were Italian immigrants Pietro and Paolina (née Longoni) Berra.[6] Pietro was originally from Malvaglio near Milan in northern Italy; he arrived at Ellis Island on October 18, 1909 at the age of 23.[7] In a 2005 interview for the Baseball Hall of Fame, Berra said, "My father came over first. He came from the old country. And he didn't know what baseball was. He was ready to go to work. And then I had three other brothers and a sister. My brother and my mother came over later on. My two oldest brothers, they were born there—Mike and Tony. John and I and my sister Josie were born in St. Louis."[8]

Berra's parents originally gave him the nickname "Lawdie", which was derived from his mother's difficulty pronouncing "Lawrence" or "Larry" correctly. He grew up on Elizabeth Avenue, across the street from boyhood friend and later competitor Joe Garagiola. That block was also home to Jack Buck early in his Cardinals broadcasting career, and it was later renamed "Hall of Fame Place".[9] Berra was a Roman Catholic,[10] and he attended South Side Catholic, now called St. Mary's High School, in south St. Louis with Garagiola. Berra has been inducted into the St. Louis Walk of Fame.[11]

He began playing baseball in local American Legion leagues, where he learned the basics of catching while playing both outfield and infield positions. He also played for a Cranston, Rhode Island team under an assumed name.[12] While playing in American Legion baseball, he received the nickname "Yogi" from his friend Jack Maguire, who, after seeing a newsreel about India,[13] said that he resembled a Hindu yogi whenever he sat around with arms and legs crossed waiting to bat or while looking sad after a losing game.[14]

Professional baseball career

Minor leagues

In 1942, the St. Louis Cardinals overlooked Berra in favor of his boyhood best friend, Joe Garagiola. On the surface, the Cardinals seemed to think that Garagiola was the superior prospect, but team president Branch Rickey actually had an ulterior motive: Knowing he was soon to leave St. Louis to take over the operation of the Brooklyn Dodgers and more impressed with Berra than he let on, Rickey apparently planned to hold Berra off until he could sign him for the Dodgers.[15] However, the Yankees signed Berra for the same $500 bonus ($9,324 in current dollar terms) the Cardinals offered Garagiola before Rickey could sign Berra to the Dodgers.

World War II and subsequent return to Minor League

During World War II, Berra served in the U.S. Navy as a gunner's mate on the attack transport USS Bayfield during the D-Day invasion of France.[16] A Second Class Seaman, Berra was one of a six-man crew on a Navy rocket boat, firing machine guns and launching rockets at the German defenses on Omaha Beach. He was fired upon, but was not hit, and later received several commendations for his bravery. During an interview on the 65th Anniversary of D-Day, Berra confirmed that he was sent to Utah Beach during the D-Day invasion as well.[17][18]

Following his military service, Berra played minor-league baseball with the Newark Bears, surprising the team's manager with his talent despite his short stature.[19] He was mentored by Hall of Famer Bill Dickey, whose uniform number Berra took. He later said, "I owe everything I did in baseball to Bill Dickey."[20]

Major leagues

Berra was called up to the Yankees and played his first game on September 22, 1946; he played 7 games that season and 83 games in 1947. He played in more than a hundred games in each of the following fourteen years. Berra appeared in fourteen World Series, including 10 World Series championships, both of which are records.

In part because Berra's playing career coincided with the Yankees' most consistent period of World Series participation, he established Series records for the most games (75), at bats (259), hits (71), doubles (10), singles (49), games caught (63), and catcher putouts (457). In Game 3 of the 1947 World Series, Berra hit the first pinch-hit home run in World Series history,[21] off Brooklyn Dodgers pitcher Ralph Branca (who later gave up Bobby Thomson's famous Shot Heard 'Round the World in 1951).[22][23]

Berra was an All-Star for 15 seasons,[3] and was selected to 18 All-Star Games (MLB held two All-Star Games in 1959 through 1962[24]).[25] He won the American League (AL) MVP award in 1951, 1954, and 1955; Berra never finished lower than fourth in the MVP voting from 1950 to 1957.[21] He received MVP votes in fifteen consecutive seasons, tied with Barry Bonds and second only to Hank Aaron's nineteen straight seasons with MVP support.[26] From 1949 to 1955, on a team filled with stars such as Mickey Mantle and Joe DiMaggio, it was Berra who led the Yankees in RBI for seven consecutive seasons.[27]

One of the most notable games of Berra's playing career came when he caught Don Larsen's perfect game in the 1956 World Series, the first of only two no-hitters ever thrown in MLB postseason play.[28] The picture of Berra leaping into Larsen's arms following Dale Mitchell's called third strike to end the game is one of the sport's most memorable images.[29]

Playing style

Berra was excellent at hitting pitches outside of the strike zone, covering all areas of the strike zone (as well as beyond) with great extension. In addition to this wide plate coverage, he also had great bat control. He was able both to swing the bat like a golf club to hit low pitches for deep home runs and to chop at high pitches for line drives. Whether changing speeds or location, pitcher Early Wynn soon discovered that "Berra moves right with you."[30] Five times, Berra had more home runs than strikeouts in a season, striking out just twelve times in 597 at-bats in 1950. The combination of bat control and plate coverage made Berra a feared "clutch hitter", proclaimed by rival manager Paul Richards "the toughest man in the league in the last three innings". Contrasting him with teammate Mickey Mantle, Wynn declared Berra "the real toughest clutch hitter", grouping him with Cleveland slugger Al Rosen as "the two best clutch hitters in the game".[30]

As a catcher Berra was outstanding: quick, mobile, and a great handler of pitchers, Berra led all American League catchers eight times in games caught and in chances accepted, six times in double plays (a major-league record), eight times in putouts, three times in assists, and once in fielding percentage. Berra left the game with the AL records for catcher putouts (8,723) and chances accepted (9,520). He was also one of only four catchers ever to field 1.000 in a season, playing 88 errorless games in 1958. He was the first catcher to leave one finger outside his glove, a style that most other catchers eventually emulated.[31]

At age 37 in June 1962, Berra showed his superb physical endurance by catching an entire 22-inning, seven-hour game against the Detroit Tigers.[32] Casey Stengel, Berra's manager during most of his playing career with the Yankees and with the Mets in 1965, once said, "I never play a game without my man".[33] According to the Win Shares formula developed by sabermetrician Bill James, Berra is the greatest catcher of all time and the 52nd-greatest non-pitching player in major-league history. Berra caught a record 173 shutouts during his career, ranking him first in this category all-time among major league catchers.[34]

Later in his career, Berra became a good defensive outfielder in Yankee Stadium's notoriously difficult left field.[35]

Yankee manager and harmonica incident

Berra retired as an active player after the 1963 World Series, and was immediately named to succeed Ralph Houk as manager of the Yankees. An unforgettable incident occurred on board the team bus in August 1964. Following a loss, infielder Phil Linz was playing his harmonica, and Berra ordered him to stop. Seated on the other end of the bus, Linz could not hear what Berra had said, and Mickey Mantle impishly informed Linz, "He said to play it louder." When Linz did so, an angry Berra slapped the harmonica out of his hands.[36] All was apparently forgotten when the Yankees rode a September surge to return to the World Series, but the team lost to the St. Louis Cardinals in seven games, after which Berra was fired. Houk, who was general manager at the time, later said the decision to fire Berra was made in late August and that the incident with Linz had nothing to do with it. Although he didn't elaborate, Houk said that he and the rest of the Yankee brain trust did not feel Berra was ready to manage.[37] Players, however, said the incident actually solidified his managerial authority and helped him lead them to the Series.[38]

Coach of New York Mets and Houston Astros

Berra was immediately signed by the crosstown Mets as a coach. He also put in four cameo appearances as a catcher early in the season. His last at-bat came on May 9, 1965, just three days shy of his 40th birthday. Berra stayed with the Mets as a coach under Stengel, Wes Westrum, and Gil Hodges for the next seven seasons, including their 1969 World Series Championship season. He then became the team's manager in 1972, following Hodges' unexpected death in spring training.[39]

The following season looked like a disappointment at first. Injuries plagued the Mets throughout the season. Midway through the 1973 season, the Mets were stuck in last place but in a very tight divisional race. In July, when a reporter asked Yogi if the season was over, he replied, "It ain't over till it's over."[40]

As the Mets' key players came back to the lineup, a late surge allowed them to win the NL East despite an 82–79 record, making it the only time from 1970 through 1980 that the NL East was not won by either their rival Philadelphia Phillies or the Pittsburgh Pirates.[41][42] When the Mets faced the 99-win Cincinnati Reds in the 1973 National League Championship Series, a memorable fight erupted between Bud Harrelson and Pete Rose in the top of the fifth inning of Game Three. After the incident and the ensuing bench-clearing brawl had subsided, fans began throwing objects at Rose when he returned to his position in left field in the bottom half of the inning. Sparky Anderson pulled Rose and his Reds off the field until order was restored. When National League president Chub Feeney threatened the Mets with a forfeit, Berra walked out to left field with Willie Mays, Tom Seaver, Rusty Staub, and Cleon Jones in order to plead with the fans to desist.[43] Yogi's Mets went on to defeat the highly favored Big Red Machine in five games to capture the NL pennant. It was Berra's second as a manager, one in each league. The Mets fell to the Oakland Athletics in the 1973 World Series, but they went the distance in a close-fought seven-game series.[44]

Berra's tenure as Mets manager ended with his firing on August 5, 1975. He had a record of 298 wins and 302 losses, which included the 1973 postseason. In 1976, he rejoined the Yankees as a coach. The team won its first of three consecutive AL titles, as well as the 1977 World Series and 1978 World Series, and (as had been the case throughout his playing days) Berra's reputation as a lucky charm was reinforced. Casey Stengel once said of his catcher, "He'd fall in a sewer and come up with a gold watch."[45] Berra was named Yankee manager before the 1984 season. Berra agreed to stay in the job for 1985 after receiving assurances that he would not be terminated, but the impatient Steinbrenner reneged, firing Berra anyway after the 16th game of the season. Moreover, instead of firing him personally, Steinbrenner dispatched Clyde King to deliver the news for him.[46] The incident caused a rift between Berra and Steinbrenner that was not mended for almost 15 years.[47]

Berra joined the Houston Astros as bench coach in 1985,[48] where he again made it to the NLCS in 1986. The Astros lost the series in six games to the Mets.[49] Berra remained a coach in Houston for three more years, retiring after the 1989 season.[50] He finished his managerial career with a regular-season record of 484–444 and a playoff record of 9–10.[51]

After George Steinbrenner ventured to Berra's home in New Jersey to apologize in person for having mishandled Berra's firing as Yankee manager, Berra ended his 14-year estrangement from the Yankee organization in 1999 and worked in spring-training camp with catcher Jorge Posada.[52]

| Team | From | To | Regular season | Post–season | Ref. | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| W | L | Win % | W | L | Win % | ||||

| New York Yankees | 1964 | 1964 | 99 | 63 | .611 | 3 | 4 | .429 | [51] |

| New York Mets | 1972 | 1975 | 292 | 296 | .497 | 6 | 6 | .500 | [51] |

| New York Yankees | 1984 | 1985 | 93 | 85 | .522 | — | [51] | ||

| Total | 484 | 444 | .522 | 9 | 10 | .474 | — | ||

Honors

In 1972, Berra was elected to the Baseball Hall of Fame.[53]

The No. 8 was retired in 1972 by the Yankees, jointly honoring Berra and Bill Dickey, his predecessor as the Yankees' star catcher.[54]

On August 22, 1988, Berra and Dickey were honored with plaques to be hung in Monument Park at Yankee Stadium. Berra's plaque calls him "A legendary Yankee" and cites his most frequent quote, "It ain't over till it's over". However, the honor was not enough to shake Berra's conviction that Steinbrenner had broken their personal agreement; Berra did not set foot in the stadium for another decade, until Steinbrenner publicly apologized to Berra.[55]

In 1996, Berra received an honorary doctorate from Montclair State University,[53] which also named its own campus stadium Yogi Berra Stadium, opened in 1998, in his honor. The stadium is also used by the New Jersey Jackals, an independent professional baseball team.[56]

In 1998, Berra appeared at No. 40 on The Sporting News list of the 100 Greatest Baseball Players,[57] and fan balloting elected him to the Major League Baseball All-Century Team.[53] At the 2008 All-Star Game at Yankee Stadium, Berra had the honor of being the last of the 49 Hall of Famers in attendance to be announced. The hometown favorite received the loudest standing ovation of the group.[58]

On July 18, 1999, Berra was honored with "Yogi Berra Day" at Yankee Stadium. Don Larsen threw the ceremonial first pitch to Berra to honor the perfect game of the 1956 World Series. The celebration marked the return of Berra to the stadium, after the end of his 14-year feud with Yankees owner George Steinbrenner. The feud had started in 1985 when Steinbrenner, having promised Berra the job of Yankees' manager for the entire season, fired him after just sixteen games. Berra then vowed never to return to Yankee Stadium as long as Steinbrenner owned the team. On that day, Yankees pitcher David Cone threw a perfect game against the Montreal Expos,[59] only the 16th time it had ever been done in Major League history.[60]

In 2008, Berra was inducted into the New Jersey Hall of Fame.[61]

Yogi Berra Museum, Learning Center, and Yogi Berra Stadium

In 1998, the Yogi Berra Museum and Learning Center[62] and Yogi Berra Stadium (home of the New Jersey Jackals and Montclair State University baseball teams) opened on the campus of Montclair State University in Upper Montclair, New Jersey. The museum is the home of various artifacts, including the mitt with which Yogi caught the only perfect game in World Series history, several autographed and "game-used" items, and nine of Yogi's championship rings.[53]

Berra was involved with the project and frequently visited the museum for signings, discussions, and other events. It was his intention to teach children important values such as sportsmanship and dedication on and off the baseball diamond.[63]

On October 8, 2014, a break-in and theft occurred at the museum, and several of Berra's World Series rings and other memorabilia were stolen.[64]

Presidential Medal of Freedom

On November 24, 2015, Berra was awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom posthumously by President Barack Obama in a ceremony at the White House attended by members of Berra's family, who accepted the award on his behalf.[65][66] At the ceremony, the President said: "Today we celebrate some extraordinary people. Innovators, artists and leaders who contribute to America's strength as a nation." Celebrating Berra's military service and remarkable baseball career, Obama used one of Berra's famous 'Yogiisms', saying, "One thing we know for sure: If you can't imitate him, don't copy him."[66]

Other activities

Berra and former teammate Phil Rizzuto were partners in a bowling alley venture in Clifton, New Jersey, originally called Rizzuto-Berra Lanes. The two eventually sold their stakes in the alley to new owners, who changed its name to Astro Bowl before selling the property to a developer, who closed the bowling alley in 1999 and converted it into retail space.[67][68]

Berra was also involved in causes related to his Italian American heritage. He was a longtime supporter of the National Italian American Foundation (NIAF) and helped fund raise for the Foundation.[69] He was inducted into the Italian American Hall of Fame in 2004.[70]

Berra was a recipient of the Boy Scouts of America's highest adult award, the Silver Buffalo Award.[71]

Based on his style of speaking, Yogi was named "Wisest Fool of the Past 50 Years" by The Economist magazine in January 2005.[72]

In the 2007 television miniseries The Bronx is Burning, Berra was portrayed by actor Joe Grifasi. In the HBO sports docudrama 61*, Berra was portrayed by actor Paul Borghese, and Hank Steinberg's script included more than one of Berra's famous "Yogi-isms". In 2009, Berra appeared in the documentary film A Time for Champions, recounting his childhood memories of soccer in his native St. Louis.[73]

Yogi and his wife Carmen were played by real-life newly married actors Peter Scolari and Tracey Shayne in the 2013 Broadway play Bronx Bombers.[74]

Personal life

Berra married Carmen Short on January 26, 1949. They had three sons and were longtime residents of Montclair, New Jersey, until Carmen's declining health caused them to move into a nearby assisted living facility. Berra's sons also played professional sports: Dale Berra played shortstop for the Pittsburgh Pirates, New York Yankees (managed by Yogi in 1984–85), and Houston Astros; Tim Berra played pro football for the Baltimore Colts in 1974; and Larry Berra played for three minor league teams in the New York Mets organization. Carmen Berra died on March 6, 2014, of complications from a stroke, at age 85; the couple had recently celebrated their 65th anniversary.[75] Following Carmen's death, the house in Montclair was listed for sale at $888,000, a reference to Yogi's uniform number.[76]

Death

Berra died at age 90 of natural causes in his sleep in West Caldwell, New Jersey, on September 22, 2015 – 69 years to the day after his MLB debut.[77][78]

The Yankees added a number "8" patch to their uniforms in honor of Berra,[79] and the Empire State Building was lit with vertical blue and white Yankee "pinstripes" on September 23.[80] New York City lowered all flags in the city to half-staff for a day in tribute.[81] A moment of silence was held before the September 23 games of the Yankees, Dodgers, Astros, Mets, Nationals, Tigers, Pirates, and his hometown St. Louis Cardinals, as well as the ALPB's Long Island Ducks.[80] The Yogi Berra Museum held a tribute on October 4.[82]

Berra's funeral services were held on September 29, and were broadcast by the YES Network. He was interred at the Gate of Heaven Cemetery in East Hanover, New Jersey.

Legacy

"Yogi-isms"

Berra was also well known for his impromptu pithy comments, malapropisms, and seemingly unintentional witticisms, known as "Yogi-isms". His "Yogi-isms" very often took the form of either an apparent tautology or a contradiction, but often with an underlying and powerful message that offered not just humor, but wisdom. Allen Barra has described them as "distilled bits of wisdom which, like good country songs and old John Wayne movies, get to the truth in a hurry."[83]

Examples

- "90 percent of baseball is mental; the other half is physical."[5]

- On why he no longer went to Rigazzi's, a St. Louis restaurant: "Nobody goes there anymore. It's too crowded."[5]

- "It ain't over till it's over." In July 1973, Berra's Mets trailed the Chicago Cubs by 9½ games in the National League East. The Mets rallied to clinch the division title in their second-to-last game of the regular season, and eventually reach the World Series.[5]

- When giving directions to Joe Garagiola to his New Jersey home, which was accessible by two routes: "When you come to a fork in the road, take it."[5]

- At Yogi Berra Day at Sportsman Park in St. Louis: "Thank you for making this day necessary."[5]

- "It's déjà vu all over again." Berra explained that this quote originated when he witnessed Mickey Mantle and Roger Maris repeatedly hitting back-to-back home runs in the Yankees' seasons in the early 1960s.[5]

- "You can observe a lot by watching."[5]

- "Always go to other people's funerals; otherwise they won't go to yours."[5]

- "I really didn't say everything I said."[84]

- "A nickel ain't worth a dime anymore"[85]

- "If you can't imitate him, don't copy him."[86]

In popular culture

The name of the cartoon character Yogi Bear was similar enough to Berra's name that he sued Hanna-Barbera for defamation, but Hanna-Barbera claimed that the similarity of the names was just a coincidence.[87]

Books

- Yogi: The Autobiography of a Professional Baseball Player, Yogi Berra and Ed Fitzgerald (1961) LOC: 61-6504

- Behind the Plate, Lawrence Yogi Berra and Til Ferdenzi (1962) ISBN 978-1-258-11403-9

- Yogi: It Ain't Over (1989) ISBN 0-07-096947-7

- The Yogi Book: I Really Didn't Say Everything I Said (1998) ISBN 0-7611-1090-9

- When You Come to a Fork in the Road, Take It! Inspiration and Wisdom from One of Baseball's Greatest Heroes (2001) ISBN 0-7868-6775-2

- What Time Is It? You Mean Now?: Advice for Life from the Zennest Master of Them All (2002) ISBN 0-7432-3768-4

- Ten Rings: My Championship Seasons (2003) ISBN 0-06-051381-0

- Let's Go, Yankees! (2006) ISBN 1-932888-81-0

- You Can Observe a Lot by Watching (2009) ISBN 978-0-470-45404-6

See also

- List of Major League Baseball career hits leaders

- List of Major League Baseball career home run leaders

- List of Major League Baseball career putouts as a catcher leaders

- List of Major League Baseball career runs scored leaders

- List of Major League Baseball career runs batted in leaders

- List of Presidential Medal of Freedom recipients

- Yogi Bear

References

- ^ Bloom, Barry M. (September 23, 2015). "Yogi was military hero before a baseball star". Major League Baseball. Retrieved June 30, 2018.

- ^ a b Sports Illustrated, July 4, 2011, p. 66.

- ^ a b c "Yogi Berra". National Baseball Hall of Fame. Retrieved April 29, 2015

- ^ "About Yogi Berra: Biography". Yogi Berra Museum & Learning Center. Archived from the original on November 13, 2011. Retrieved April 29, 2015.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Berra, Yogi (1998). The Yogi Book. New York: Workman Publishing. p. 9. ISBN 0-7611-1090-9.

- ^ DeVito, Carlo (2014). Yogi: The Life & Times of an American Original. Chicago: Triumph Books. pp. 1–5. ISBN 9781572439450.

- ^ Williams, Dave (April 1, 2013). Bridging Two Dynasties: The 1947 New York Yankees. Society for American Baseball Research. University of Nebraska Press. Chapter 44: Yogi Berra. p. 170. Archived at Google Books. Retrieved April 29, 2015.

- ^ "Yogi Berra Interview". Academy of Achievement. American Academy of Achievement. June 1, 2005. Archived from the original on March 8, 2014. Retrieved August 15, 2012.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Waldstein, David (October 21, 2011). "An Incubator of Baseball Talent". The New York Times. p. B14. Retrieved August 10, 2013.

- ^ Blount, Roy, Jr. (April 2, 1984). "Yogi". Sports Illustrated. Archived from the original on August 11, 2011. Retrieved November 1, 2011.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ St. Louis Walk of Fame. "St. Louis Walk of Fame Inductees". stlouiswalkoffame.org. Retrieved April 25, 2013.

- ^ Iannuccilli, Ed (August 28, 2012). "More About Yogi". Italian American Writer. Archived from the original on March 8, 2014. Retrieved August 15, 2013.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ http://baseballhall.org/hof/berra-yogi

- ^ Raab, Scott (January 1, 2002). "Yogi Berra: catcher, 76, Montclair, New Jersey. (What I've Learned)". Esquire. Retrieved February 24, 2013. (subscription required)

- ^ "Lawrence Peter "Yogi" Berra". qotd.org. Retrieved April 29, 2015.

- ^ Dorman, Larry (January 19, 2010). "Berra Calls 'em as He Sees 'em". The New York Times. p. B14. Retrieved June 5, 2011.

- ^ "Military Service". yogiberramuseum.org. Archived from the original on September 25, 2015.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ 65 Year Anniversary of D-Day – Yogi Berra Feature. YouTube. June 8, 2009.

- ^ Peter, Josh (May 12, 2015). "Yogi Berra at 90: Quips and quotes from a Yankees icon". USA Today. Retrieved September 22, 2015.

- ^ "Bill Dickey". National Baseball Hall of Fame. Retrieved September 22, 2015.

- ^ a b "Statistics". Yogi Berra Museum. Retrieved September 23, 2015.

- ^ Madden, Bill (September 23, 2015). "Yogi Berra dead at 90: Yankees legend, Baseball Hall of Famer was lovable character, American hero". New York Daily News. Retrieved September 23, 2015.

- ^ Goldstein, Richard (August 17, 2010). "Bobby Thomson Dies at 86; Hit Epic Home Run". The New York Times. Retrieved September 23, 2015.

- ^ Donnelly, Patrick (2012)."Midsummer Classics: Celebrating MLB's All-Star Game". "there were two games a year from 1959 to 1962" ..."all players who were named to the AL or NL roster were credited one appearance per season." SportsData. Retrieved April 12, 2015

- ^ "Yogi Berra". Baseball-Reference.com. Retrieved April 29, 2015

- ^ "Yogi Berra Baseball Stats". Baseball Almanac. Retrieved September 23, 2015.

- ^ Collecting Sports Legends (2008) by Joe Orlando, pp. 84

- ^ "Roy Halladay throws second no-hitter in postseason history". ESPN. October 7, 2010

- ^ Klopsis, Nick (October 8, 2012). "56 years later, Don Larsen and Yogi Berra reminisce about perfect game". Newsday. Retrieved September 22, 2015.

- ^ a b Kahn, Roger. (2003). "The Gathering Storm". October Men: Reggie Jackson, George Steinbrenner, Billy Martin, and the Yankees' Miraculous Finish in 1978. Orlando, Florida: Harcourt. p. 174. ISBN 0-15-100628-8. Retrieved September 18, 2015.

- ^ Acocella, Nick (October 18, 2006). "Berra was great, which was as close to good as possible". ESPN. Retrieved November 29, 2010.

- ^ "Sunday, June 24, 1962, New York Yankees". Baseball-Reference.com. Retrieved August 15, 2013.

- ^ Burns, Ken. "Inning 7 – The Capital of Baseball", Baseball, 1994.

- ^ "The Encyclopedia of Catchers – Trivia December 2010 – Career Shutouts Caught". The Encyclopedia of Baseball Catchers. Retrieved December 29, 2015.

- ^ Gallagher, Mark (2003). The Yankee Encyclopedia. p. 31.

- ^ Bouton, Jim (1970). Ball Four. New York: Wiley. ISBN 9780020306658.

- ^ Reichler, Joe (February 28, 1965). "Notes: His biggest mistake was Yogi, Houk says". The Tuscaloosa News. Associated Press. Retrieved July 14, 2014.

- ^ DeVito, Carlo (2014). Yogi: The Life & Times of an American Original. Triumph Books. p. 244. ISBN 9781600789663. Retrieved August 8, 2015.

- ^ Berra, Lindsay (July 12, 2013). "Remembering 'Grampa' Yogi's Mets career". MLB.com. Retrieved September 22, 2015.

- ^ "How people started saying 'It ain't over till it's over'". BBC.com. September 23, 2015. Retrieved February 15, 2017.

- ^ Von Benko, George (July 7, 2005). "Notes: Phils–Pirates rivalry fading". Philadelphia Phillies. Major League Baseball. Archived from the original on July 14, 2011. Retrieved January 3, 2011.

From 1974 to 1980, the Phillies and Pirates won all seven National League East titles (Phillies four, Pirates three).

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Pirates perform rare three-peat feat 4–2". USA Today. September 28, 1992. p. 5C.

The Pirates...won three (NL East titles) in a row from 1970 to 1972.

- ^ "Our World Fall 1973 Part 1". YouTube. August 19, 2009. Retrieved August 15, 2013.

- ^ Wright, Brian (September 12, 2013). "The 1973 Mets: A year to believe". Amazin' Avenue. Retrieved September 22, 2015.

- ^ "Yogi Berra Quotes". Baseball-Almanac.com. Retrieved August 15, 2013.

- ^ Merron, Jeff (June 16, 2003). "The List: Steinbrenner's worst". ESPN.com. Retrieved August 15, 2013.

- ^ Bondy, Filip (January 6, 1999). "Yogi and Boss End Feud Hug and Make Up at Berra's N.J. Museum". New York Daily News. Retrieved September 24, 2015.

- ^ "Hall of Famer Yogi Berra joins Houston Astros staff". Kentucky New Era. November 19, 1985.

- ^ "Revisit the '86 NLCS". ESPN.com. Retrieved September 22, 2015.

- ^ "Names in the News". Los Angeles Times. September 26, 1989. Retrieved September 22, 2015.

- ^ a b c d "Yogi Berra". Baseball Reference. Sports Reference. Retrieved September 23, 2015.

- ^ Araton, Harvey (February 21, 2013). "Posada Is Set to Help, as Berra Helped Him". The New York Times (New York ed.). p. B21.

- ^ a b c d "About Yogi". Yogi Berra Museum. Retrieved September 22, 2015.

- ^ "Retired Uniform Numbers". Baseball Almanac. Retrieved September 22, 2015.

- ^ Friend, Harold (September 22, 2010). "George Steinbrenner Realized He Had To Apologize to Yogi Berra". Bleacher Report. Retrieved September 22, 2015.

- ^ "About Floyd Hall Enterprises". New Jersey Jackals. Retrieved September 22, 2015.

- ^ "Baseball's 100 Greatest Players". Baseball Almanac. Archived from the original on July 12, 2007. Retrieved September 22, 2015.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ 2008 MLB All Star Game: Hall of Famers walk onto the field. YouTube. July 23, 2008.

- ^ Ackert, Kristie (July 18, 2009). "Yankees celebrate 10th anniversary of David Cone's perfect game". New York Daily News. Retrieved September 18, 2009.

- ^ Bondy, Filip (July 19, 1999). "For Berra Family, Day Is Also PerfecT". New York Daily News. Retrieved September 24, 2015.

- ^ O'Connor, Julie (May 4, 2008). "Gala planned for New Jersey Hall of Fame inductees". The Star-Ledger. Newark, New Jersey: New Jersey On-Line LLC. Retrieved December 2, 2011.

- ^ "Yogi Berra Museum". Yogi Berra Museum. Retrieved November 29, 2010.

- ^ Posnanski, Joe (July 4, 2011). "Yogi Berra Will Be A Living Legend Even After He's Gone". Sports Illustrated. Vol. 115, no. 1. pp. 64–68. Archived from the original on June 30, 2011.

- ^ Foss, Mike (October 9, 2014). "World Series rings stolen from Yogi Berra Museum". USA Today. Retrieved October 19, 2014.

- ^ Boeck, Scott (November 16, 2015). "Yogi Berra, Willie Mays are recipients of the Presidential Medal of Freedom". USA Today. Retrieved November 16, 2015.

- ^ a b Phil Helsel – "Obama honoring Spielberg, Streisand and more with medal of freedom," NBC News, November 24, 2015. Retrieved 2015-11-25

- ^ Galant, Debra (December 10, 2000). "Bowling, Once a First Date, Now Takes Back Seat". The New York Times. Retrieved September 23, 2015.

- ^ Mielach, David (April 4, 2012). "Yogi Berra on Baseball and Business". Business News Daily. Retrieved September 23, 2015.

- ^ "The National Italian American Foundation (NIAF) Mourns the Passing of Carmen Berra". National Italian American Foundation. Retrieved September 23, 2015.

- ^ "Ernest Borgnine, Yogi Berra & Paul Tagliabue To be Inducted into Italian American Hall of Fame *Lawrence Babbio & Louis Lamoriello To be Honored at NY Gala*". National Italian American Foundation. April 13, 2004. Retrieved September 23, 2015.

- ^ Scouting (September 2003), pp. 38

- ^ "Wisest Fools". The Economist. London. January 27, 2005.

- ^ A Time for Champions (2009). KETC/Cappy Productions

- ^ Kepler, Adam W. (October 21, 2013). "A Broadway Run for 'Bronx Bombers'". The New York Times. Retrieved February 6, 2014.

- ^ Vinton, Nathaniel; Madden, Bill (March 7, 2014). "Yogi Berra's wife of 65 years, Carmen, dead at 85 following complications from recent stroke". New York Daily News. Retrieved March 7, 2014.

- ^ Goldman, Jeff (April 30, 2014). "PHOTOS: Yogi Berra's Montclair home is for sale". NJ.com. Retrieved September 23, 2015.

- ^ Burke, Don. "Yankees legend Yogi Berra dead at 90", New York Post, September 23, 2015. (accessed September 23, 2015)

- ^ Rudansky, Andrew; = Jamieson, Alastair (September 23, 2015). "Yogi Berra, Yankees Icon and MLB Hall of Famer, Dies at 90 – NBC News". NBCNews.com. Retrieved September 23, 2015.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: extra punctuation (link) - ^ Perry, Dayn (September 23, 2015). "Yankees to honor Yogi Berra with No. 8 patch on jersey sleeve". CBS Sports. Retrieved September 23, 2015.

- ^ a b Stephen, Eric (September 23, 2015). "Empire State Building to honor Yogi Berra with Yankee pinstripes". SB Nation. Retrieved September 23, 2015.

- ^ "Flags Flying At Half-Staff In NYC In Honor Of Yankees Great Yogi Berra". CBS New York. September 23, 2015. Retrieved September 24, 2015.

- ^ Mazzola, Jessica (September 28, 2015). "How to watch Yogi Berra's funeral on Tuesday". NJ.com. Retrieved September 28, 2015.

- ^ Stahl, Jeremy (September 23, 2015). "Yogi Berra Wasn't Trying to Be Witty". Slate. Retrieved September 23, 2015.

- ^ "I really didn't say everything I said". Fox News.

- ^ Subramanian, Pras (September 23, 2015). "'A nickel ain't worth a dime anymore' - Yogi's financial wisdom". Yahoo! Finance. Yahoo!. Retrieved July 4, 2017.

- ^ Mather, Victor; Rogers, Katie (September 23, 2015). "Behind the Yogi-isms: Those Said and Unsaid". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved September 26, 2017.

- ^ Laura Lee (2000), The Name's Familiar II, Pelican Publishing, p. 93, ISBN 9781455609178

Further reading

- Barra, Allen (2009). Yogi Berra: Eternal Yankee. New York: W. W. Norton & Company. ISBN 0-393-06233-3. OCLC 227016802.

External links

- Career statistics from MLB, or ESPN, or Baseball Reference, or Fangraphs, or Baseball Reference (Minors)

- Yogi Berra managerial career statistics at Baseball-Reference.com

- Yogi Berra at the Baseball Hall of Fame

- Yogi Berra Museum site

- Yogi Berra Quotes, A comprehensive list of "Yogi-isms"

- Yogi Berra at Find a Grave

- 1925 births

- 2015 deaths

- Baseball coaches from Missouri

- American sportspeople of Italian descent

- American League All-Stars

- American League Most Valuable Player Award winners

- American military personnel of World War II

- Baseball players from Missouri

- Burials at Gate of Heaven Cemetery (East Hanover, New Jersey)

- Houston Astros coaches

- Major League Baseball bench coaches

- Major League Baseball catchers

- Major League Baseball first base coaches

- Major League Baseball hitting coaches

- Major League Baseball players with retired numbers

- National Baseball Hall of Fame inductees

- New York Mets coaches

- New York Mets managers

- New York Mets players

- New York Yankees coaches

- New York Yankees managers

- New York Yankees players

- Operation Overlord people

- Presidential Medal of Freedom recipients

- Sportspeople from Essex County, New Jersey

- Sportspeople from St. Louis

- United States Navy sailors

- Writers from Missouri