Brazil nut: Difference between revisions

P. S. Sena (talk | contribs) No edit summary |

reorg section & subtitles; copy edit, replace one ref & provide Pubmed refs; this section needs more editing & fact-checking |

||

| Line 148: | Line 148: | ||

Brazil nuts are a common ingredient in [[mixed nuts]] where, because of their large size, they tend to rise to the top, an example of [[granular convection]], which for this reason is often called the "[[Brazil nut effect]]". |

Brazil nuts are a common ingredient in [[mixed nuts]] where, because of their large size, they tend to rise to the top, an example of [[granular convection]], which for this reason is often called the "[[Brazil nut effect]]". |

||

=== |

===Brazil nut oil=== |

||

| ⚫ | |||

Brazil nut oil contains 75% unsaturated fatty acids composed mainly of oleic and linolenic acids, as well as the [[phytosterol]], [[beta-sitosterol]],<ref>{{cite journal|journal=Int J Vitam Nutr Res|year=2013|volume=83|issue=5|pages=263-70|doi=10.1024/0300-9831/a000168|title=Phytosterol content and fatty acid pattern of ten different nut types|authors=Kornsteiner-Krenn M, Wagner KH, Elmadfa I|pmid=25305221}}</ref> and fat-soluble vitamin E.<ref>{{cite journal|journal=Int J Food Sci Nutr|year=2006|volume=57|issue=3-4|pages=219-28|title=Fatty acid profile, tocopherol, squalene and phytosterol content of brazil, pecan, pine, pistachio and cashew nuts|authors=Ryan E, Galvin K, O'Connor TP, Maguire AR, O'Brien NM|pmid=17127473}}</ref> Extra virgin oil can be obtained during the first pressing of the nuts, possibly used as a substitute for [[olive oil]] for its mild and pleasant flavor. |

|||

| ⚫ | As well as its food use, Brazil nut oil is also used as a lubricant in clocks, for making artists' paints, and in the cosmetics industry. Engravings in Brazil nut shells were supposedly used as decorative jewelry by the indigenous tribes in Bolivia, although no examples still exist. Because of its hardness, Brazil nut shell has often been pulverized and used as an abrasive to polish softer materials such as metals and even ceramics (in the same way as [[jeweler's rouge]] is used). A high luster could be acquired by a final application of [[carnauba wax]], only produced in north-eastern Brazil. |

||

Nut oil is also rich in [[magnesium]] and has the highest known concentrations of [[selenium]] of any nut oil.<ref name="moodley">{{cite journal|journal=J Environ Sci Health B|year=2007|volume=42|issue=5|pages=585-91|title=Elemental composition and chemical characteristics of five edible nuts (almond, Brazil, pecan, macadamia and walnut) consumed in Southern Africa|authors=Moodley R, Kindness A, Jonnalagadda SB|pmid=17562467}}</ref> |

|||

==Brazil nut oil== |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | |||

The seed oil is highly nutritious, containing 75% unsaturated fatty acids composed mainly of palmitic, oleic, and linolenic acids, as well as the phytosterol sistosterol, and the fat-soluble vitamins A and E. Extravirgin oil can be obtained during the first pressing of the seeds, which can be used as a substitute for olive oil because of its mild and pleasant flavor. The seeds are also rich in magnesium, thiamine, and have the highest known concentrations of selenium (126 ppm) of any seed in the world, which has antioxidant properties. Some studies indicate that the consumptionof selenium is associated with a reduction in the risk of prostate cancer and recommend the consumption of these seeds as a preventive measure. The proteins in the seeds are very rich in sulfur amino acids, such as cysteine (8%) and methionine (18%); the presence of methionine enhances the adsorption of selenium and other minerals. Due to its anti-free radical, antioxidant, and moisturizing properties, the cosmetic industry uses the seed oil from this tree in anti-aging skin products. It is also considered one of the best conditioners for damaged and dehydrated hair.<ref>Morais, Luiz Roberto Barbosa Química de oleaginosas : valorização da biodiversidade amazônica = Chemistry of vegetable oils : valorization of the amazon biodiversity. — Belém, PA : Ed. do Autor, 2012. — (Oleaginosas).633.850981</ref> |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | |||

{| class="wikitable" |

{| class="wikitable" |

||

|- |

|- |

||

! |

! Characteristic !! Unit !! Presentation |

||

|- |

|- |

||

| |

| Composition || --- || liquid |

||

|- |

|- |

||

| Color || --- || translucent yellow |

| Color || --- || translucent yellow |

||

|- |

|- |

||

| Scent || --- || |

| Scent || --- || mild, typical of nuts |

||

|- |

|- |

||

| [[Acid value]] || |

| [[Acid value]] || mg KOH/g || < 20.0 |

||

|- |

|- |

||

| [[Peroxide value]] || |

| [[Peroxide value]] || meq O<sub>2</sub>/kg || < 10.0 |

||

|- |

|- |

||

| |

| Iodine index || g I<sub>2</sub>/100g || 90-110 |

||

|- |

|- |

||

| |

| Saponification index || mg KOH/g || 180-210 |

||

|- |

|- |

||

| [[Density]] || 25ºC g/ml || 0 |

| [[Density]] || 25ºC g/ml || 0.910-0925 |

||

|- |

|- |

||

| [[Refractive index]] (40ºC) || --- || 1, |

| [[Refractive index]] (40ºC) || --- || 1,460-1,480 |

||

|- |

|- |

||

| [[Melting point]] || °C || 4 |

| [[Melting point]] || °C || 4 |

||

|} |

|} |

||

Composition of fatty acids in Brazil nut oil<ref name=moodley/> |

|||

* [[Palmitic acid]], 16-20% |

|||

{| Class = "wikitable" |

|||

* [[Palmitoleic acid]], 0.5-1.2% |

|||

|- |

|||

* [[Stearic acid]], 9-13% |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

|- |

|||

* [[Linoleic acid]], 33-38% |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

|- |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

| [[Stearic acid]] || || Weight% 9 to 13.0 |

|||

|- |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

|- |

|||

| [[Linoleic acid]] || ||% weight 33.0 to 38.0 |

|||

|- |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

|- |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

|- |

|||

|} |

|||

===Other uses=== |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | As well as its food use, Brazil nut oil is also used as a lubricant in clocks, for making artists' paints, and in the cosmetics industry. Engravings in Brazil nut shells were supposedly used as decorative jewelry by the indigenous tribes in Bolivia, although no examples still exist. Because of its hardness, Brazil nut shell has often been pulverized and used as an abrasive to polish softer materials such as metals and even ceramics (in the same way as [[jeweler's rouge]] is used). A high luster could be acquired by a final application of [[carnauba wax]], only produced in north-eastern Brazil. |

||

===Wood=== |

===Wood=== |

||

Revision as of 15:56, 9 January 2015

| Brazil nut tree | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | |

| (unranked): | |

| (unranked): | |

| (unranked): | |

| Order: | |

| Family: | |

| Genus: | Bertholletia |

| Species: | B. excelsa

|

| Binomial name | |

| Bertholletia excelsa Humb. & Bonpl.

| |

The Brazil nut (Bertholletia excelsa) is a South American tree in the family Lecythidaceae, and also the name of the tree's commercially harvested edible seed.

Order

The Brazil nut family is in the order Ericales, as are other well-known plants such as blueberries, cranberries, sapote, gutta-percha, tea, gooseberries, phlox and persimmons.

Brazil nut tree

The Brazil nut tree is the only species in the monotypic genus Bertholletia. It is native to the Guianas, Venezuela, Brazil, eastern Colombia, eastern Peru, and eastern Bolivia. It occurs as scattered trees in large forests on the banks of the Amazon River, Rio Negro, Tapajós, and the Orinoco. The genus is named after the French chemist Claude Louis Berthollet.

The Brazil nut is a large tree, reaching 50 m (160 ft) tall and with a trunk 1 to 2 m (3.3 to 6.6 ft) in diameter, making it among the largest of trees in the Amazon rainforests. It may live for 500 years or more, and according to some authorities often reaches an age of 1,000 years.[1] The stem is straight and commonly without branches for well over half the tree's height, with a large emergent crown of long branches above the surrounding canopy of other trees.

The bark is grayish and smooth. The leaves are dry-season deciduous, alternate, simple, entire or crenate, oblong, 20–35 cm (7.9–13.8 in) long and 10–15 cm (3.9–5.9 in) broad. The flowers are small, greenish-white, in panicles 5–10 cm (2.0–3.9 in) long; each flower has a two-parted, deciduous calyx, six unequal cream-colored petals, and numerous stamens united into a broad, hood-shaped mass.

Hazards

In Brazil, it is illegal to cut down a Brazil nut tree. As a result, they can be found outside production areas, in the backyards of homes and near roads and streets. The fruit containing nuts is very heavy and rigid, and it poses a serious threat to vehicles and persons passing under the tree. At least one person has died after being hit on the head by a falling fruit.[2] As the Brazil nut is a botanical seed, and unlike botanical nuts, the density of the fruit makes them sink in fresh water, which can cause clogging of waterways in riparian areas.

Reproduction

Brazil nut trees produce fruit almost exclusively in pristine forests, as disturbed forests lack the large-bodied bees of the genera Bombus, Centris, Epicharis, Eulaema, and Xylocopa which are the only ones capable of pollinating the tree's flowers, with different bee genera being the primary pollinators in different areas, and different times of year.[3][4][5] Brazil nuts have been harvested from plantations, but production is low and is currently not economically viable.[6][7][8]

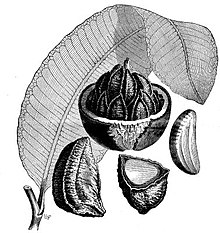

The fruit takes 14 months to mature after pollination of the flowers. The fruit itself is a large capsule 10–15 cm (3.9–5.9 in) in diameter, resembling a coconut endocarp in size and weighing up to 2 kg (4.4 lb). It has a hard, woody shell 8–12 mm (0.31–0.47 in) thick, which contains eight to 24 triangular seeds 4–5 cm (1.6–2.0 in) long (the "Brazil nuts") packed like the segments of an orange.

The capsule contains a small hole at one end, which enables large rodents like the agouti to gnaw it open. They then eat some of the seeds inside while burying others for later use; some of these are able to germinate into new Brazil nut trees. Most of the seeds are "planted" by the agoutis in shady places, and the young saplings may have to wait years, in a state of dormancy, for a tree to fall and sunlight to reach it, when it starts growing again. Capuchin monkeys have been reported to open Brazil nuts using a stone as an anvil.

Nomenclature

Despite their name, the most significant exporter of Brazil nuts is not Brazil but Bolivia, where they are called nuez de Brasil. In Brazil, these nuts are called castanhas-do-pará (literally "chestnuts from Pará"), but Acreans call them castanhas-do-acre instead. Indigenous names include juvia in the Orinoco area.

Though it is commonly called the Brazil nut, in botanical terms it is the seed from the fruit of this tree. To a botanist, a nut is a hard-shelled indehiscent fruit.

In the United States Brazil nuts were once known by the epithet "nigger toes,"[9] though the term fell out of favor as public use of the racial slur became increasingly unacceptable. They can be seen being sold in a market under this name in a scene from the 1922 Stan Laurel film The Pest.

Nut production

Around 20,000 tons of Brazil nuts are harvested each year, of which Bolivia accounts for about 50%, Brazil 40%, and Peru 10% (2000 estimates).[10] In 1980, annual production was around 40,000 tons per year from Brazil alone, and in 1970, Brazil harvested a reported 104,487 tons of nuts.[6]

Effects of harvesting

Brazil nuts for international trade can come from wild collection rather than from plantations. This has been advanced as a model for generating income from a tropical forest without destroying it. The nuts are gathered by migrant workers known as castanheiros.

Analysis of tree ages in areas that are harvested show that moderate and intense gathering takes so many seeds, not enough are left to replace older trees as they die. Sites with light gathering activities had many young trees, while sites with intense gathering practices had hardly any young trees.[11]

Statistical tests were done to determine what environmental factors could be contributing to the lack of younger trees. The most consistent effect was found to be the level of gathering activity at a particular site. A computer model predicting the size of trees where people picked all the nuts matched the tree size data gathered from physical sites that had heavy harvesting.

When harvesting and collecting the ripened cases that fall off the trees, harvesters have to be cautious because they are easily heavy enough to kill a person. Fatal accidents are not uncommon among collectors – they stop work at once if the wind suddenly strengthens, because this can cause a bombardment.[12]

Uses

Nutrition

| Nutritional value per 100 g (3.5 oz) | |

|---|---|

| Energy | 2,743 kJ (656 kcal) |

12.27 g | |

| Starch | 0.25 g |

| Sugars | 2.33 g |

| Dietary fiber | 7.5 g |

66.43 g | |

| Saturated | 15.137 g |

| Monounsaturated | 24.548 g |

| Polyunsaturated | 20.577 g |

14.32 g | |

| Tryptophan | 0.141 g |

| Threonine | 0.362 g |

| Isoleucine | 0.516 g |

| Leucine | 1.155 g |

| Lysine | 0.492 g |

| Methionine | 1.008 g |

| Cystine | 0.367 g |

| Phenylalanine | 0.630 g |

| Tyrosine | 0.420 g |

| Valine | 0.756 g |

| Arginine | 2.148 g |

| Histidine | 0.386 g |

| Alanine | 0.577 g |

| Aspartic acid | 1.346 g |

| Glutamic acid | 3.147 g |

| Glycine | 0.718 g |

| Proline | 0.657 g |

| Serine | 0.683 g |

| Vitamins | Quantity %DV† |

| Thiamine (B1) | 51% 0.617 mg |

| Riboflavin (B2) | 3% 0.035 mg |

| Niacin (B3) | 2% 0.295 mg |

| Vitamin B6 | 6% 0.101 mg |

| Folate (B9) | 6% 22 μg |

| Vitamin C | 1% 0.7 mg |

| Vitamin E | 38% 5.73 mg |

| Minerals | Quantity %DV† |

| Calcium | 12% 160 mg |

| Iron | 14% 2.43 mg |

| Magnesium | 90% 376 mg |

| Manganese | 53% 1.223 mg |

| Phosphorus | 58% 725 mg |

| Potassium | 22% 659 mg |

| Sodium | 0% 3 mg |

| Zinc | 37% 4.06 mg |

| Other constituents | Quantity |

| Water | 3.48 g |

| Selenium | 1917 μg |

| †Percentages estimated using US recommendations for adults,[13] except for potassium, which is estimated based on expert recommendation from the National Academies.[14] | |

Brazil nuts are 14% protein, 12% carbohydrates, and 66% fat by weight, and 85% of their calories come from fat; a 100 g serving provides 656 total calories.[15] The fat components are 23% saturated, 38% monounsaturated, and 32% polyunsaturated.[15][16] Due to their high polyunsaturated fat content, primarily omega-6 fatty acids, shelled Brazil nuts may quickly become rancid.

Nutritionally, Brazil nuts are an excellent source (> 19% of the Daily Value, DV) of dietary fiber (30% DV) and various vitamins and dietary minerals. A 100 g serving (75% of one cup) of Brazil nuts contains rich content of thiamin (54% DV), vitamin E (38% DV), magnesium (106% DV), phosphorus (104% DV), manganese (58% DV) and zinc (43% DV) (right table). Brazil nuts are perhaps the richest dietary source of selenium, with a one ounce (28 g) serving of 6 nuts supplying 774% DV.[15] This is 10 times the adult U.S. Recommended Dietary Allowances, more even than the Tolerable Upper Intake Level, although the amount of selenium within batches of nuts varies greatly.[17] Brazil nut oil is clear and light amber in color, with a pleasant, sweet smell and taste suitable for salad dressing.

The European Union has imposed strict regulations on the import from Brazil of Brazil nuts in their shells, as the shells have been found to contain high levels of aflatoxins, which can lead to liver cancer.[18]

Brazil nuts contain small amounts of radium, a radioactive element, in about 1–7 nCi/g or 40–260 Bq/kg, about 1000 times higher than in several other common foods.[19] According to Oak Ridge Associated Universities, this is not because of elevated levels of radium in the soil, but due to "the very extensive root system of the tree."[20]

Brazil nuts are a common ingredient in mixed nuts where, because of their large size, they tend to rise to the top, an example of granular convection, which for this reason is often called the "Brazil nut effect".

Brazil nut oil

Brazil nut oil contains 75% unsaturated fatty acids composed mainly of oleic and linolenic acids, as well as the phytosterol, beta-sitosterol,[21] and fat-soluble vitamin E.[22] Extra virgin oil can be obtained during the first pressing of the nuts, possibly used as a substitute for olive oil for its mild and pleasant flavor.

Nut oil is also rich in magnesium and has the highest known concentrations of selenium of any nut oil.[23]

Physicochemical composition of Brazil nut oil

| Characteristic | Unit | Presentation |

|---|---|---|

| Composition | --- | liquid |

| Color | --- | translucent yellow |

| Scent | --- | mild, typical of nuts |

| Acid value | mg KOH/g | < 20.0 |

| Peroxide value | meq O2/kg | < 10.0 |

| Iodine index | g I2/100g | 90-110 |

| Saponification index | mg KOH/g | 180-210 |

| Density | 25ºC g/ml | 0.910-0925 |

| Refractive index (40ºC) | --- | 1,460-1,480 |

| Melting point | °C | 4 |

Composition of fatty acids in Brazil nut oil[23]

- Palmitic acid, 16-20%

- Palmitoleic acid, 0.5-1.2%

- Stearic acid, 9-13%

- Oleic acid, 36-45%

- Linoleic acid, 33-38%

- Saturated fats, 25%

- Unsaturated fats, 75%

Other uses

As well as its food use, Brazil nut oil is also used as a lubricant in clocks, for making artists' paints, and in the cosmetics industry. Engravings in Brazil nut shells were supposedly used as decorative jewelry by the indigenous tribes in Bolivia, although no examples still exist. Because of its hardness, Brazil nut shell has often been pulverized and used as an abrasive to polish softer materials such as metals and even ceramics (in the same way as jeweler's rouge is used). A high luster could be acquired by a final application of carnauba wax, only produced in north-eastern Brazil.

Wood

The lumber from Brazil nut trees (not to be confused with Brazilwood) is of excellent quality, but logging the trees is prohibited by law in all three producing countries (Brazil, Bolivia and Peru). Illegal extraction of timber and land clearances present a continuing threat.[24]

See also

References

- ^ Bruno Taitson (January 18, 2007). "Harvesting nuts, improving lives in Brazil". World Wildlife Fund. Archived from the original on May 23, 2008. Retrieved July 17, 2012.

- ^ "Agricultor morre após ser atingido por ouriço de castanha, no Amazonas", Amazonas. Template:Pt icon

- ^ Nelson, B.W.; Absy, M.L.; Barbosa, E.M.; Prance, G.T. (1985). "Observations on flower visitors to Bertholletia excelsa H. B. K. and Couratari tenuicarpa A. C. Sm.(Lecythidaceae)". Acta Amazonica. 15 (1): 225–234. Retrieved April 8, 2008.

- ^ Moritz, A. (1984). "Estudos biológicos da floração e da frutificação da castanha-do-Brasil (Bertholletia excelsa HBK)". 29. Retrieved April 8, 2008.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ http://www.hindawi.com/journals/psyche/2012/978019/

- ^ a b Scott A. Mori. "The Brazil Nut Industry --- Past, Present, and Future". The New York Botanical Garden. Retrieved July 17, 2012.

- ^ Tim Hennessey (March 2, 2001). "The Brazil Nut (Bertholletia excelsa)". Archived from the original on January 11, 2009. Retrieved July 17, 2012.

- ^ Enrique G. Ortiz. "The Brazil Nut Tree: More than just nuts". Archived from the original on July 6, 2007. Retrieved July 17, 2012.

{{cite web}}:|archive-date=/|archive-url=timestamp mismatch; February 16, 2008 suggested (help) - ^ Brazil, Matt (July 14, 2000). "Actually, My Hair Isn't Red". The Wall Street Journal. Dow Jones & Company, Inc. Retrieved July 6, 2009.

Hearing angmo so often took me back to my childhood, when my friends and I used the words Jew and Gyp (the latter short for Gypsy) as verbs, meaning to cheat. At that time, in the 1960s, other racial epithets, these based on physical appearance, were commonly heard: cracker, slant-eye, bongo lips, knit-head. To digress to the ludicrous, Brazil nuts were called "nigger toes."

- ^ Chris Collinson; Duncan Burnett; Victor Agreda (Spring 2000). "Economic Viability of Brazil Nut Trading in Peru" (PDF). Natural Resources Institute, University of Greenwich. Retrieved July 17, 2012.

- ^ Attention: This template ({{cite doi}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by doi:10.1016/j.tree.2004.03.022, please use {{cite journal}} (if it was published in a bona fide academic journal, otherwise {{cite report}} with

|doi=10.1016/j.tree.2004.03.022instead. - ^ http://qi.com/infocloud/brazil-nuts

- ^ United States Food and Drug Administration (2024). "Daily Value on the Nutrition and Supplement Facts Labels". Retrieved March 28, 2024.

- ^ National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine; Health and Medicine Division; Food and Nutrition Board; Committee to Review the Dietary Reference Intakes for Sodium and Potassium (2019). Oria, Maria; Harrison, Meghan; Stallings, Virginia A. (eds.). Dietary Reference Intakes for Sodium and Potassium. The National Academies Collection: Reports funded by National Institutes of Health. Washington, DC: National Academies Press (US). ISBN 978-0-309-48834-1. PMID 30844154.

- ^ a b c "Nutrition facts for Brazil nuts, dried, unblanched, 100 g serving". nutritiondata.com. Conde Nast; US Department of Agriculture National Nutrient Database, version SR-21. 2014. Retrieved December 30, 2014.

- ^ "Nuts, brazilnuts, dried, unblanched" (PDF). United States Department of Agriculture. Retrieved July 17, 2012.

- ^ Chang, Jacqueline C.; Walter H. Gutenmann, Charlotte M. Reid, Donald J. Lisk (1995). "Selenium content of Brazil nuts from two geographic locations in Brazil". Chemosphere. 30 (4): 801–802. doi:10.1016/0045-6535(94)00409-N. PMID 7889353. 0045-6535.

{{cite journal}}: Cite has empty unknown parameters:|quotes=and|month=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "Commission Decision of 4 July 2003 imposing special conditions on the import of Brazil nuts in shell originating in or consigned from Brazil". Official Journal of the European Union. July 5, 2012. Retrieved July 17, 2012.

- ^ "Radioactivity in Nature". Idaho State University. Retrieved December 30, 2014.

- ^ "Brazil Nuts". Oak Ridge Associated Universities. January 20, 2009. Retrieved July 17, 2012.

- ^ "Phytosterol content and fatty acid pattern of ten different nut types". Int J Vitam Nutr Res. 83 (5): 263–70. 2013. doi:10.1024/0300-9831/a000168. PMID 25305221.

{{cite journal}}: Cite uses deprecated parameter|authors=(help) - ^ "Fatty acid profile, tocopherol, squalene and phytosterol content of brazil, pecan, pine, pistachio and cashew nuts". Int J Food Sci Nutr. 57 (3–4): 219–28. 2006. PMID 17127473.

{{cite journal}}: Cite uses deprecated parameter|authors=(help) - ^ a b "Elemental composition and chemical characteristics of five edible nuts (almond, Brazil, pecan, macadamia and walnut) consumed in Southern Africa". J Environ Sci Health B. 42 (5): 585–91. 2007. PMID 17562467.

{{cite journal}}: Cite uses deprecated parameter|authors=(help) - ^ "Greenpeace Activists Trapped by Loggers in Amazon". Greenpeace. October 18, 2007. Retrieved July 17, 2012.

External links

- Template:IUCN2006 Listed as Vulnerable (VU A1acd+2 cd v2.3)

- Peres, C.A.; et al. (2003). "Demographic threats to the sustainability of Brazil nut exploitation". Science. 302 (December 19): 2112–2114. doi:10.1126/science.1091698. PMID 14684819.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help) (Overharvesting of Brazil nuts as threat to regeneration.) - Brazil nuts, nutrition, nuts and nut recipes

- New York Botanical Gardens Brazil Nuts Page

- Brazil nuts' path to preservation, BBC News.

- Intensive harvests 'threaten Brazil nut tree future'

- Brazil nut (Bertholletia excelsa), The Encyclopedia of Earth

- IUCN Red List vulnerable species

- Edible nuts and seeds

- Lecythidaceae

- Trees of Brazil

- Trees of Bolivia

- Trees of Colombia

- Trees of Guyana

- Trees of Peru

- Trees of Venezuela

- Trees of the Amazon

- Tropical agriculture

- Crops originating from the Americas

- Crops originating from Brazil

- Crops originating from Bolivia

- Crops originating from Peru

- Crops originating from Colombia

- Vulnerable plants

- Amazon oil