City of Adelaide (1864)

34°50′30″S 138°30′31″E / 34.841633°S 138.508736°E

City of Adelaide. Hand-coloured lithograph by Thomas Dutton, 1864.

| |

| History | |

|---|---|

| Name |

|

| Owner |

|

| Operator | |

| Port of registry |

|

| Route | London — Plymouth — Adelaide — Port Augusta — London (typical 1864–87) |

| Builder | Pile, Hay & Co |

| Launched | 7 May 1864 |

| Commissioned | 1923 |

| Decommissioned | 1948 |

| Maiden voyage | 6 August 1864 |

| Out of service | 1893–1922; since 1948 |

| Stricken | Removed from register 7 February 1895 |

| Homeport | |

| Identification |

|

| Nickname(s) | The City |

| Status | Awaiting restoration at Port Adelaide, South Australia |

| Badge | |

| General characteristics | |

| Type | |

| Tonnage | 791 NRT[1] |

| Length |

|

| Beam | 33.3 ft (10.15 m)[1] |

| Depth | 18.8 ft (5.73 m)[1] |

| Sail plan |

|

City of Adelaide is a clipper ship, built in Sunderland, England, and launched on 7 May 1864. It was built by Pile, Hay and Co. to transport passengers and goods between Britain and Australia. Between 1864 and 1887 she made 23 annual return voyages from London and Plymouth to Adelaide, South Australia and played an important part in the immigration of Australia. On the return voyages she carried passengers, wool, and copper from Adelaide and Port Augusta to London. From 1869[2] to 1885 she was part of Harrold Brothers' "Adelaide Line" of clippers.

After 1887, the ship carried coal around the British coast, and timber across the Atlantic. In 1893, she became a floating hospital in Southampton, and in 1923 was purchased by the Royal Navy. The ship was commissioned in the Royal Navy as HMS Carrick (to avoid confusion with the newly commissioned HMAS Adelaide), and based in Scotland as a training ship. In 1948, she was decommissioned and donated to the Royal Naval Volunteer Reserve Club, and towed into central Glasgow for use as the club's headquarters and remained on the River Clyde until 1989 when she was damaged by flooding. In order to safeguard the vessel, she was protected as a listed building, but in 1991 she sank at her mooring. Carrick was recovered by the Scottish Maritime Museum the following year, and moved to a private slipway adjacent to the museum's site in Irvine.

Restoration work began, but funding ceased in 1999, and from 2000 the future of the ship was in doubt. After being served with an eviction notice by the owners of the slipway, the Scottish Maritime Museum was forced to seek the deconstruction of the ship on more than one occasion, while rescue proposals were developed by groups based in Sunderland and South Australia. At a conference convened by the Duke of Edinburgh in 2001, the decision was made to revert the ship's name to City of Adelaide. In 2010, the Scottish Government decided that the ship would be moved to Adelaide, to be preserved as a museum ship, and the duke formally renamed her at a ceremony in 2013. In September 2013, the ship was moved by barge from Scotland to the Netherlands to prepare for transport to Australia. In late November 2013, loaded on the deck of a cargo ship, City of Adelaide departed Europe bound for Port Adelaide, where she arrived on 3 February 2014.

Significance

City of Adelaide is the world's oldest surviving clipper ship, of only two that survive – the other is Cutty Sark (built 1869; a tea-clipper and now a museum ship and tourist attraction in Greenwich, Southeast London). With Cutty Sark and HMS Gannet (built 1878; a sloop-of-war in Chatham), City of Adelaide is one of only three surviving ocean-going ships of composite construction to survive.[3] [note 1]

City of Adelaide is one of three surviving sailing ships, and of these the only passenger ship, to have taken emigrants from the British Isles (the other two are Edwin Fox and Star of India).[note 2] City of Adelaide is the only surviving purpose-built passenger sailing ship.[5]

Adding to her significance as an emigrant ship, City of Adelaide is the last survivor of the timber trade between North America and the United Kingdom. As this trade peaked at the same time as conflicts in Europe, a great mass of refugees sought cheap passage on the timber-trade ships, that would otherwise be returning empty, creating an unprecedented influx of new immigrants in North America.

Having been built in the years prior to Lloyd's Register publishing their rules for composite ships, City of Adelaide is an important example in the development of naval architecture.[5][6]

The UK's Advisory Committee on National Historic Ships describes the significance of City of Adelaide in these terms:[3]

She highlights the early fast passenger-carrying and general cargo trade to the Antipodes. Her composite construction illustrates technical development in 19th shipbuilding techniques and scientific progress in metallurgy and her self-reefing top sails demonstrate the beginnings of modern labour saving technologies. Her service on the London to Adelaide route between 1864 and 1888 gives her an unrivalled associate status as one of the ships contributing to the growth of the Australian nation.

In recognition of her significance, until departing the United Kingdom in 2013, City of Adelaide was an A-listed structure in Scotland, part of the National Historic Fleet of the United Kingdom, and listed in the Core Collection of the United Kingdom.[3]

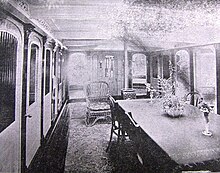

Construction

City of Adelaide was designed to carry both passengers and cargo between England and Australia. Cabins could accommodate first-class and second-class passengers, and the hold could be fitted out for carrying steerage-class emigrants when needed.[citation needed]

City of Adelaide is a composite ship with timber planking on a wrought-iron frame. This method of construction provides the structural strength of an iron ship combined with the insulation of a timber hull. Unlike iron ships, where copper would cause corrosion in contact with the iron, the timber bottoms of composite ships could be sheathed with copper to prevent fouling. The iron frames meant that composite ships could carry large amounts of canvas sail. Composite ships were therefore some of the fastest ships afloat.[7]

Composite ships were built in the relatively short period from c. 1860 to 1880. City of Adelaide was built in 1864 before Lloyd's Register recognised and endorsed composite ships in 1867. Before this, all composite ships were labelled by Lloyds as being "Experimental".[6] Being a developmental technology in 1864 meant that many of the structural features on City of Adelaide are now regarded as being 'over-engineered', particularly when compared to other later composite ships like Cutty Sark (1869). For example, the frame spacing on City of Adelaide is much closer together than seen on other composite ships. This extra strength from 'over-engineering', together with the good fate to have benefited from human habitation and/or husbandry through to the late 1990s, has likely been a major factor why City of Adelaide has survived, even after being grounded on Kirkcaldy Beach in South Australia for a week in 1874 (see below).[citation needed]

Service history

Conception

After having gained much experience on the London to Adelaide run with his ship Irene, Captain David Bruce had City of Adelaide built expressly for the South Australia trade.[8] The order for the ship was given to William Pile, Hay and Company of Sunderland and she was launched on 7 May 1864.[9] Captain Bruce took a quarter-share ownership.[10]

City of Adelaide is frequently referred to as being owned by the British shipping firm Devitt and Moore, but they were only the managing agents in London. Partner Joseph Moore snr. was a syndicate member, holding a quarter-share in the ship.[11]

The remaining two quarter-shares were taken up by South Australian interests – Harrold Brothers[12] who were the agents in Adelaide, and Henry Martin,[13] the working proprietor of the Yudnamutana and Blinman copper mines in the Flinders Ranges.

South Australian trade – 1864–87

The ship spent 23 years making annual runs to and from South Australia, playing an important role in the development of the colony. Researchers have estimated that a quarter of a million South Australians can trace their origins to passengers on City of Adelaide.[14]

At least six diaries kept by passengers describing voyages have survived from the 23 return voyages between London and Adelaide.[15]

City of Adelaide was among the fastest clippers on the London—Adelaide run, sharing the record of 65 days with Yatala, which was later broken only by Torrens.[16]

On 24 August 1874, the ship was stranded on Kirkcaldy Beach near Grange, six miles (9.7 km) south of Semaphore near Adelaide. A board at the time were over 320 people, including one of the diarists, a Scot named James McLauchlan. An outbreak of scarlet fever had occurred during the voyage and seven people died. Two babies were born aboard during the voyage – one was "born dead".[17]

Upon reaching South Australian waters at the end of this voyage, severe gales were encountered resulting in the stranding of City of Adelaide. The storms also caused incidents and losses of other vessels along the South Australian coast. The schooner Mayflower, on her way from Port Broughton to Port Adelaide, lost one of her crew overboard and he drowned: the crewman was on his way to Port Adelaide to meet his wife who was one of the migrants aboard City of Adelaide.[18] Amongst the cargo on this voyage were two Scottish Deerhounds, bred by the Marquis of Lorne, John Campbell, 9th Duke of Argyll, and being imported by Sir Thomas Elder.[19] A day after the stranding the passengers were removed by steam tugs. City of Adelaide was refloated on 4 September after much of the cargo had been discharged and much of the rigging temporarily removed. The ship was virtually undamaged.

By the 1880s, City of Adelaide was also calling at Port Augusta, South Australia on return voyages. At Port Augusta, copper from Henry Martin's Blinman and Yudnamutana copper mines in the Flinders Ranges and wool from outback sheep stations was loaded before racing to the wool sales in London. During this time, in 1881, the ship was rerigged as a barque.

Route of 1874 voyage

This map traces the route of the 1874 voyage from the latitudes and longitudes provided in the diary of James McLauchlan.[17]

Notable passengers

- Sir Frederick Aloysius Weld GCMG – sixth Premier of New Zealand, and later served as Governor of Western Australia, Governor of Tasmania, and Governor of the Straits Settlements.

- Cyril Maude – English stage and film actor.

- Alfred Sandover MBE – donor of the Sandover Medal.

- Matilda Methuen – wife of Peter Waite a South Australian pastoralist, businessman, company director and public benefactor.

- Frances Goyder – wife of George Goyder a surveyor in South Australia who established Goyder's line of rainfall.

- Frederick Bullock – mayor of Adelaide from 1891 to 1892. His diary as a 15-year-old passenger survives.[20]

Coal trade – 1887–88

In 1887, City of Adelaide was sold to Dover coal merchant, Charles Havelock Mowll, for use in the collier trade carrying coal from the Tyne to Dover.

Timber trade – 1888–93

In 1888, City of Adelaide was sold to Belfast-based timber merchants Daniel and Thomas Stewart Dixon, and was used to carry timber in the North Atlantic trade.[citation needed]

By the start of the 18th century, Britain had exhausted its supplies of the great oaks that had built the Royal Navy. The lack of large trees was problematic as they were a necessity for masts for both war and merchant shipping. A thriving timber import business developed between Britain and the Baltic region but was unpopular for economic and strategic reasons.[21] The Napoleonic Wars and a Continental blockade had a large impact on the Baltic trade and so Britain looked to the North American colonies that were still loyal.[citation needed]

The North Atlantic timber trade became a massive business and timber was British North America's most important commodity. In one summer, 1,200 ships were loaded with timber at Quebec City alone.[citation needed]

As timber is a very bulky cargo, it required many ships to carry it from North America to Britain, but there was little demand for carrying goods on the return voyages. However, there was a market for carrying migrants, so many of the timber ships turned to the migrant trade to fill their unused capacity. Since timber exports tended to peak at the same time as conflicts in Europe, a great mass of refugees sought cheap passage across the Atlantic. This created an unprecedented influx of new immigrants in North America.[citation needed]

The timber trade not only brought immigrants to British North America but also played a very important role in keeping them there. While many of those disembarking from the timber-trade ships headed south to the United States, many stayed in British North America. At the peak of the trade in the 1840s, 15,000 Irish loggers were employed in the Gatineau region alone at a time when the population of Montreal was only 10,000.[citation needed]

City of Adelaide was home-ported in Belfast and from there frequented several British North American ports, most frequently Miramichi, New Brunswick.[citation needed]

Of the thousands of sailing ships involved in the timber trade between North America and the United Kingdom, City of Adelaide is the last survivor.[citation needed]

Hospital ship 1893–1922

City of Adelaide ended her sailing career in 1893, when purchased by Southampton Corporation for £1750 to serve as a floating isolation hospital. During one year of operation, 23 cases of scarlet fever were cared for. In 2009, the National Health Service named a new hospital at Millbrook, Southampton, in honour of the ship – the Adelaide Health Centre.[22]

Royal Navy and Royal Naval Volunteer Reserve – 1922–48

In 1923, City of Adelaide was purchased by the Admiralty and towed to Irvine, Scotland, where she was placed on the same slipway that she was to return to in 1992. After conversion to a training ship, she was towed to Greenock and commissioned as a Naval Drill Ship for the newly constituted Clyde Division of the Royal Naval Volunteer Reserve (RNVR).[23] As the new cruiser HMAS Adelaide had been commissioned only the previous year, to avoid confusion of two British Empire ships named Adelaide the clipper was renamed HMS Carrick.[24]

R.N.V.R. Club (Scotland) – 1948–90

After the war the ship was scheduled for breaking up, but through the work of Commodore James Graham, Duke of Montrose, Vice-Admiral Cedric S. Holland and Admiral Sir Charles Morgan, she was presented by the Admiralty to the R.N.V.R. Club (Scotland), an organisation founded by Lieutenant commander J. Alastair Montgomerie in the autumn of 1947.[25] The towing of HMS Carrick upriver from Greenock to Harland and Wolff's shipyard at Scotstoun on 26 April 1948, was known as 'Operation Ararat'. A grant of 5,000 pounds was received from the King George's Fund for Sailors and 500 pounds was donated from the City of Glasgow War Fund.[23]

After fitting out, Carrick was towed further up-river to a berth at Custom House Quay, just above Jamaica Bridge. A plaque on board commemorates the opening ceremony of the club, which was carried out by Admiral of the Fleet Andrew Cunningham, 1st Viscount Cunningham of Hyndhope. The ship stayed there until January 1954 when the Clyde Navigation Trust decided to move her to the opposite side of the river at Carlton Place.[23]

By the mid-1980s the Club realised that it could not afford to maintain its floating clubrooms. It commenced seeking ways of securing the ship's future and passing on ownership, and contacted various bodies with potential interest including the then recently established Scottish Maritime Museum.

Museum ship – 1990 to present

Clyde Ship Trust

In 1989 there proved to be some need for haste, when the ship was flooded when the deck edge was trapped beneath the wharf on a very low tide. The Club in some desperation took the option on its insurance of having the vessel declared a total loss. To facilitate the preservation of the ship, Glasgow District Council applied for Listed Building status. Historic Scotland agreed to take the unusual step of listing a historic vessel as Category A – normally only applied to historic buildings. Listing was viewed as a boost to the preservation project.

By 1990 a new body, the Clyde Ship Trust, had been formed and, in March of that year, had purchased the vessel for £1. Under the control of the new Trust the vessel was dismasted and prepared for removal and in August 1990, was towed downstream to Princes Dock.

Early in 1991, for reasons that have not been clearly identified, the vessel sank at her moorings. The Clyde Ship Trust was placed in a position of embarrassment, for, being already in debt, it was unable to put forward the funds required for a major salvage operation. It became necessary for other organisations to step in to attempt to prevent the total loss of the ship.

Scottish Maritime Museum

In 1992, with the encouragement of Historic Scotland and Scottish Enterprise, who provided the bulk of the £500,000 required to fund the rescue, the ship was salvaged by the Scottish Maritime Museum and moved to Irvine, North Ayrshire, with the expectation to preserve and eventually restore the vessel.[26] The ship was identified as part of the UK National Historic Ships Core Collection.[3]

In September 1993 City of Adelaide was slipped on the same slipway near the Scottish Maritime Museum on which she had been converted in 1923. From then a programme of work was planned and operated on two fronts: preservation and restoration; and to allow public access and good quality interpretation.

Work continued until 1999 when Scotland regained its own parliament, UK funding sources for the Scottish Maritime Museum dried up. The museum was subsequently evicted from the slipway site, placing the museum under great pressure to remove City of Adelaide and the museum began to seek alternative options for the clipper.

Clipper Ship City of Adelaide Ltd. (CSCOAL)

The ownership of the vessel transferred from the Scottish Maritime Museum to Clipper Ship City of Adelaide Ltd. (CSCOAL) on 6 September 2013.[27]

Rescue and transport to Australia

Background

From 1992, City of Adelaide was owned by the Scottish Maritime Museum. After slipping the clipper in 1993, the museum began a programme of work to preserve and restore the historic ship.

In May 1999 Scotland regained its own parliament. A side effect of this was that previous UK funding sources for the Scottish Maritime Museum dried up.[28] This then had a snowball effect on the Scottish Maritime Museum. An application for funding for the Museum's other major project, under the UK Heritage Lottery Fund, was rejected. Due to the eroded revenue position, the local municipality reduced its funding, and other grant-aiding organisations adopted a similar position.

Following the restructuring of local government in Scotland the Scottish Maritime Museum, as an independent charitable trust, appealed to the Scottish Executive for support. The Executive commissioned a report through the Scottish Museums Council that recommended the sale of City of Adelaide. The Museum began to receive government support but it was conditional on no government funds being spent on the vessel. In 1999 all work on City of Adelaide stopped and the shipwrights were moved to other projects.[26]

The Scottish Maritime Museum had agreed a contract with the owner of the slipway on which City of Adelaide was stored, specifying a peppercorn rent of £1 a year. However the contract included a penalty clause requiring payment of £50,000 per year should the owner require the museum to vacate the slipway. SMM were given notice to quit in April 1999, and rental began to accrue.[29] Faced with these potential demands, and unable to find a buyer for the vessel, in May 2000 the trustees of the Scottish Maritime Museum applied to North Ayrshire Council for listed building consent to deconstruct City of Adelaide.[30] The council received over 100 objections, including representations from nine significant maritime heritage organisations around the world. Members of the UK and Scottish Parliaments objected, as well as the Australian Foreign Minister Alexander Downer and Australian ex-Senator and diplomat Robert Hill.[31] The Council refused demolition in February 2001.[30]

Duke of Edinburgh Conference

As a result of an initiative from The Duke of Edinburgh a conference was convened in Glasgow in September 2001 to discuss the future of the vessel. The conference was chaired by Admiral of the Fleet Sir Julian Oswald, and in addition to the Duke of Edinburgh was attended by representatives of the High Commission of Australia in London, Save the City of Adelaide 1864 Group, City of Sunderland Council, Cutty Sark Trust, Department for Culture, Media and Sport, Heritage Lottery Fund, Historic Scotland, North Ayrshire Council, National Historic Ships Committee, Scottish Executive, Scottish Maritime Museum, Government of South Australia, and Sunderland Maritime Heritage. The conference concluded that City of Adelaide is one of the most important historic vessels in the UK, but that resources available in Scotland were insufficient to ensure her survival. The Duke of Edinburgh proposed that The Maritime Trust and the SMM should work in partnership to fund a first phase of work. This phase would see the vessel removed from the slipway, on which the initial work had been completed, and placed on a barge or similar vessel and transhipped to another location. The Maritime Trust would take the lead in raising the funding support for the first phase.

Sunderland Maritime Heritage and the Adelaide-based Save the City of Adelaide 1864 Action Group both presented the conference with proposals for the vessel. The conference agreed that both organisations should now look to securing funding support for their proposals and an active dialogue would be maintained by all concerned. The aim of the Maritime Trust and the Scottish Maritime Museum would be that final transfer to either the Sunderland Maritime Trust or the Save the City of Adelaide 1864 Group would take place as quickly as possible. The final decision of the conference was that as the significance of the vessel lay in her activities under her original name, she should in future be known simply as City of Adelaide.[32]

Edwards proposal

In 2003 businessman Mike Edwards donated funds for preservation and a feasibility study for the ship's restoration as a tourist adventure sailing ship for Travelsphere Limited. In February 2006 the results of the feasibility studies identified that the cost to comply with current maritime passenger safety regulations for seagoing vessels would be more expensive than building a replica. The studies concluded that it would be more cost-effective to turn City of Adelaide into a static exhibit. Edwards decided not to take up his original option of acquiring City of Adelaide but his charitable efforts had provided another three years of reprieve and a protective cover to shield the clipper from the elements.[33]

After three years the Scottish Maritime Museum was back in its original predicament, but the situation was worsened as the volunteer organisations that had previously been campaigning to acquire City of Adelaide had now been on hiatus since 2003. The situation was further exacerbated as over the previous decade and a half, the Irvine River near the slipway had become heavily silted. Environmental regulations were now also more stringent, and the cost of dredging the river near sensitive bird breeding grounds and wetlands was thought to be unaffordable. City of Adelaide was therefore regarded as unrecoverable from the slipway.[34]

In May 2006 the Scottish Maritime Museum applied again to North Ayrshire Council for consent to deconstruct the ship,[35] at an estimated cost of £650,000.[36] After the proposal was gazetted by the council 132 letters of objection were received, including representations from preservation groups in Sunderland and Australia, and from several Australian institutions.

On 18 April 2007 North Ayrshire Council approved the application to deconstruct of the clipper, subject to the approval of Historic Scotland.[37] Just a few weeks later a major fire broke out on Cutty Sark, prompting a rethink on the future of the only other substantially surviving clipper ship.[38]

Rescue proposals

The North Ayrshire Council decision prompted the South Australian organization Save the City of Adelaide 1864 Action Group to reform after being in hiatus since the 2003 Edwards proposal. Upon the subsequent news of the Cutty Sark fire, the Group's Peter Roberts and Peter Christopher highlighted that the fire made it critical to save City of Adelaide.[39]

A group from Sunderland subsequently renewed calls to save the ship. The Sunderland City of Adelaide Recovery Foundation (SCARF) proposed to remove the vessel and store her on private land whilst working on plans to develop a maritime museum around the restored City of Adelaide. The Scottish Maritime Museum stated that SCARF were welcome to take the ship should they have the money to save her.[40]

The Save the City of Adelaide 1864 Action Group became formally constituted as Clipper Ship "City of Adelaide" Ltd (CSCOAL). The CSCOAL plan was to transport City of Adelaide to Port Adelaide in South Australia in time for the state's 175th Jubilee in 2011. In March 2009 CSCOAL launched an e-petition on the 10 Downing Street website, calling on the British Prime Minister to intervene to save City of Adelaide and gift the ship "to the people of South Australia".[36] Federal and state e-petitions were also launched in Australia. The former was later featured in an exhibition of "Living Democracy" at the Museum of Australian Democracy, Canberra.[41] In November 2009 an open letter, signed by 66 eminent Australians, was sent to the British Prime Minister and the First Minister of Scotland, urging them to prevent the demolition of City of Adelaide. Led by the Governor of South Australia, Rear Admiral Kevin Scarce, other notable signatories included the current and four former Lord Mayors of Adelaide; former Australian Prime Minister Bob Hawke, national and state politicians including Senator Simon Birmingham (who was to figure prominently in the clipper's rescue later), Alexander Downer, Robert Hill, and John Bannon; senior Australian Navy officers; academics; business figures and Australian Living Treasures Dr Basil Hetzel, Jack Mundey and Julian Burnside.[42]

Meanwhile, SCARF member and Sunderland councillor Peter Maddison sought to raise awareness through a four-day 'occupation' of the vessel in October.[43]

The Scottish Maritime Museum called for tenders for the demolition or deconstruction of City of Adelaide, which closed on 23 November 2009. Deconstruction of the vessel would involve scientific recording and potential preservation of sections of the ship.[29] CSCOAL submitted a tender, though unlike the other tenders its proposal involved removing the ship as a whole rather than in pieces.[44]

The Scottish Maritime Museum found itself in a Catch-22 position: the punitive charges arising from their failure to vacate the slipway were now sufficient to bankrupt the museum, but they did not have sufficient funds to scientifically deconstruct the vessel.[45] Had the museum gone into administration its nationally significant collection would have been dispersed. The alternative for the Scottish Government was to fund either the deconstruction of City of Adelaide, or her removal from Scotland. A conference was held in December 2009 at which the main stakeholders discussed the possible options for saving the ship.[46]

Review of options

In March 2010, in response to questions in the Scottish Parliament from Irene Oldfather, MSP for Cunninghame South which includes Irvine, the Scottish Minister for Culture and External Affairs Fiona Hyslop said the Scottish Government was working closely with a number of stakeholders to explore realistic options for securing the future of City of Adelaide and that Historic Scotland had commenced an assessment of these options. Hyslop said she had met a delegation from CSCOAL and had subsequently spoken to the South Australian Minister for Transport Patrick Conlon.[47] Historic Scotland's assessment looked at four options: deconstruction; removal elsewhere in Scotland; removal to Sunderland by SCARF; or removal to Australia by CSCOAL.[48] The options appraisal was carried out by DTZ with advice from Sir Neil Cossons, former Director of the National Maritime Museum and a former Chair of English Heritage, with extensive experience in maritime heritage.[49]

In May 2010 Minister Hyslop accepted from Irene Oldfather a copy of a diary kept by James Anderson McLauchlan, a 21-year-old Scot who migrated to South Australia on City of Adelaide in 1874. The diary begins with his departure from Dundee, and his subsequent 80-day voyage to South Australia. The presentation was intended to highlight the importance of City of Adelaide from the human perspective, and the experiences "shared by thousands of other people who made the journey across the globe for a new life".[50] In July 2010 The Duke of Edinburgh gave a rare radio interview reflecting on the 40th anniversary of the rescue of the SS Great Britain, and commented on the hideous trap that City of Adelaide was in.[51]

Hyslop announced on 28 August 2010 that City of Adelaide would not be deconstructed, and that CSCOAL had been identified as the preferred bidder.[48] The DTZ report identified the CSCOAL as the only feasible option which would not involve destruction of the ship. The CSCOAL bid was considered to meet the assessment criteria, despite some funding uncertainties. The rival bid from SCARF was not considered to be technically feasible, with significant risks identified in relation to funding and the expertise available to the SCARF team.[29] Costs associated with transport to Australia were estimated at A$5 million.[52]

Sunderland-based SCARF congratulated the Australian group but stated that their campaign to keep the ship in the United Kingdom would continue.[53]

Project preliminaries

A detailed bathymetric / hydrographic survey of the River Irvine had been previously undertaken to develop the strategies for recovering City of Adelaide from the riverbank. This was necessary as the river had silted up over the twenty years since the clipper was slipped.[54]

In advance of the vessel's removal, the Scottish Maritime Museum commissioned Headland Archaeology to undertake a detailed 3D laser survey of City of Adelaide. This serves as a detailed record of the ship, and enabled the transportation cradle to be designed and built with great precision in South Australia.[54][55] Virtual tours of the inside and outside of the clipper were also created during the laser survey.[56]

An early stage in the preparatory work involved cleaning and treatment of the timbers. This was completed by the Scottish Maritime Museum in December 2010.[57]

Preparation for transport to Australia

In 2011, donor companies from across South Australia completed fabrication of CSCOAL's 100-tonne, A$1.2-million, steel cradle to be placed under the ship to move her. The first cradle components arrived at the Scottish Maritime Museum in January 2012 for assembly on site.[58] The load lifting capacity of the cradle was certified on 23 March 2012 in readiness for assembly under the ship.[54]

In late February 2012 protestors from Sunderland-based SCARF again occupied the ship in an attempt to prevent her removal to Australia.[59]

Unrelated to the SCARF protest, a delay to the project of nearly a year occurred as the Scottish Maritime Museum went through protracted negotiations with the slipway owners for access to their land to enable the removal of the clipper.[54]

Meanwhile, CSCOAL utilised the delay by shipping the clipper's timber rudder to South Australia as the 'pathfinder' to explore and test Customs and Quarantine-related issues with respect to exporting from the UK, and importing into Australia. The rudder arrived in Adelaide in December 2012.[60] The rudder had been built at Fletchers Slip in South Australia after the original was lost in a storm in South Australian waters in 1877.[61] Sunderland-based SCARF threatened legal action towards CSCOAL, and built a wooden replica rudder as a protest.

The access agreement between the Scottish Maritime Museum and the slipway owners was resolved in March 2013.[54] Immediately CSCOAL sent a project manager, Richard Smith, to Scotland to manage the activity that commenced a couple of weeks later of disassembling the cradle, and reassembling it beneath and around the clipper.[62]

The actual transport of City of Adelaide from Scotland to South Australia started in September 2013, when the clipper on her cradle was transferred using self-propelled modular transporters to a barge for transport to Chatham, Kent. On 20 September 2013 City of Adelaide left the Irvine River aboard the barge towed by the tug Dutch Pioneer, and entered open water, commencing her journey south.[63] City of Adelaide arrived at Chatham Docks on 25 September 2013.[64]

Meanwhile, the South Australian media reported that the departure to Australia could not be confirmed. A federal election on 7 September had led to a change in government, and in the meantime the funding to cover the journey to Australia had not been approved. CSCOAL were briefly left "in limbo".[65] CSCOAL arranged for the vessel to be towed upstream to Greenwich, and moored near Cutty Sark, a few days ahead of a ceremony on 18 October at which the Duke of Edinburgh formally renamed Carrick as City of Adelaide.[66]

On the day prior the ceremony, the Australian Parliamentary Secretary for the Environment Simon Birmingham, announced the Australian Government had approved the grant of A$850,000 enabling transport arrangements to be made to move the ship from the UK to Australia.[67] Representatives of SCARF staged a protest on the day of the ceremony, and stated that they were seeking an export ban which would prevent removal of the ship from the UK.[66]

On 24 October City of Adelaide arrived at Dordrecht in the Netherlands, to undergo the necessary treatment to satisfy Australian quarantine requirements.[68] Following fumigation, the clipper was lifted aboard the heavy-lift ship MV Palanpur on 22 November 2013 for transport from the Netherlands bound for South Australia.[69][70]

Final voyage

One hundred and forty-nine years after her first journey to Adelaide, City of Adelaide embarked on her last trip to the South Australian coast following a course reminiscent of the vessel's service in both the North Atlantic timber trade and the South Australian service.[71] The old ship's journey commenced at 13:15 Central European Time on 26 November 2013, departing Rotterdam, Netherlands on the deck of MV Palanpur.[71][72] Effectively representing her old timber trade voyages, City of Adelaide crossed the Atlantic arriving in the United States' port of Norfolk, Virginia on 9 December.[71][73] On 13 December, Palanpur continued southward to rejoin the historic clipper route between the UK and Australia off the coast of Brazil.[71]

On 5 January 2014,[74] the passage briefly departed from the historic route for Palanpur to take on fuel in Cape Town, South Africa, a port frequented by City of Adelaide on northbound voyages and last visited in 1890.[71] Steaming from Cape Town, the voyage strayed from the historic clipper route a final time, calling on Port Hedland, Western Australia (between 23 and 26 January) where Palanpur offloaded six locomotives from Virginia.[71][75] Following the voyage's Western Australia stop, the final leg of City of Adelaide's last passage concluded with arrival at the Outer Harbor of its home port, Port Adelaide, at 6:30 am on 3 February 2014.[71][74][76]

Temporary location in Port Adelaide

After arriving at Berth 18 in the Port River on 3 February, City of Adelaide was craned from Palanpur onto the 800 tonne barge Bradley. This was a lengthy operation due to the need to "skid" the 450 tonne vessel and her 100 tonne cradle across the deck of Palanpur between the ship's cranes before she could be off-loaded.[77][78]

On the evening of 6 February she was then moved upstream to Dock 1 in Port Adelaide's inner harbour, where she will remain for 6–12 months until a final location is selected and prepared. Fletcher's Slip was for many the preferred site,[74] but other sites such as Cruickshanks Corner and the Queens Wharf near Hart's Mill were considered. A celebration for the ship's 150th anniversary was held on 17 May 2014.[79][80] On 28 September 2015 David Brown of the Clyde Cruising Club presented the bible from the SV Carrick to the current owners in Port Adelaide for display in the ship.

In April 2017 the South Australian Government announced that Dock 2 would become the precinct to house all of Port Adelaide's historic ships.,[81] but this site is considered "virtually inaccessible" by the City of Adelaide Preservation Trust, which would instead prefer a regional city such as Port Augusta, or interstate.[82]

On 18 July 2017 Mrs Pamela Whittle (née Bruce, great granddaughter of Captain David Bruce) made a significant donation to the ongoing project to preserve the ship. The Clipper Ship Board has determined that it will be used to recreate the Captain's quarters within the restored saloon.[83]

A replica Coat of Arms commissioned by the Adelaide City Council was unveiled on the stern of the ship by the Lord Mayor of Adelaide, Martin Haese on 15 October 2017.

On 10 January 2018 the ship was moved a short distance within Dock One in order to remove it from an adjacent housing development project,[84] and on 15 March 2018 a children's activity book about the ship was launched.[85]

In November 2018 the wheel fitted to the ship by the Royal Navy in 1923, when it was named HMS Carrick, was unveiled within the City of Adelaide.

On 29 November 2019 City of Adelaide was towed to her permanent home in Dock 2, Port Adelaide.[86]

Permanent home

City of Adelaide is now in Dock 2, but still on the barge Bradley. It is planned to move the ship from the barge onto the adjoining land in 2021. CSCOAL has secured a long term peppercorn lease for the land from the South Australian Government, and plans to develop a seaport village, with City of Adelaide as its centre-piece.[87]

-

City of Adelaide being welcomed by a piper as she enters the inner harbour of Port Adelaide,

6 February 2014 -

City of Adelaide aboard Bradley barge in the inner harbour of Port Adelaide,

6 February 2014 -

City of Adelaide being nudged into her temporary location in Dock 1, Port Adelaide,

6 February 2014 -

A salute by fire-fighting vessel MV Gallantry for City of Adelaide's 150th anniversary, 17 May 2014

-

City of Adelaide's 150th anniversary cake,

17 May 2014 -

Scotch College pipe band and highland dancers at City of Adelaide's 150th anniversary, 17 May 2014

-

David Brown Clyde Cruising Club presenting SV Carrick bible to Creagh OConnor AM Pt Adelaide

-

The Lord Mayor of the City of Adelaide, Martin Haese, signs the Visitor book inside the historic clipper ship City of Adelaide.

-

This location map shows the former location of the City of Adelaide in Dock One, Port Adelaide

-

Schools are now regularly bringing groups of students to visit City of Adelaide

-

Tours are now being conducted inside the ship 3 times daily. Access is via external stairs.

-

Interior preservation works, upper deck, view towards stern. 6 May 2018

-

City of Adelaide being moved to Dock 2, Port Adelaide,

29 November 2019

See also

Notes

- ^ The wreck of the composite clipper Ambassador (1869), a beached skeleton, also rests on a beach in Strait of Magellan, near Estancia San Gregorio, Chile.[4]

- ^ SS Great Britain, a sail-steamship, also carried migrants from the British Isles.

References

- ^ a b c d Lloyd's Register of British and Foreign Shipping. Lloyd's Register. 1871. Retrieved 21 December 2014.

- ^ "Advertising". Evening Journal. Adelaide. 20 September 1869. p. 1 Edition: Late. Retrieved 17 October 2015 – via Trove.

- ^ a b c d "City of Adelaide". National Register of Historic Vessels. National Historic Ships. Archived from the original on 11 January 2011. Retrieved 15 July 2010.

- ^ "Chile – Magellan Strait – wreck of clipper Ambassador near Estancia San Gergorio". Flickr. 1 February 2009. Retrieved 22 May 2012.

- ^ a b "World Significance". City of Adelaide – the Splendid Clipper Ship. CSCOAL. Retrieved 21 November 2013.

- ^ a b Roberts, Peter (2010). "Composite Clippers". The Royal Institution of Naval Architects 1860–2010. Royal Institution of Naval Architects: 84. Retrieved 22 November 2013.

- ^ Lubbock, Basil (1991). The Colonial Clippers. New York: Kessinger Books. pp. 144–45. ISBN 1-4179-6416-2.

Lubbock, B. (1921) The Colonial Clippers 34 MB PDF - ^ "Shipping Intelligence". South Australian Register. Adelaide. 8 November 1864. p. 2. Retrieved 21 May 2011 – via Trove.

- ^ "1864 Conception". City of Adelaide – the Splendid Clipper Ship. CSCOAL. Retrieved 15 July 2010.

- ^ "Capt. David Bruce". City of Adelaide – the Splendid Clipper Ship. CSCOAL. Retrieved 15 July 2010.

- ^ "Devitt and Moore". City of Adelaide – the Splendid Clipper Ship. CSCOAL. Archived from the original on 29 April 2010. Retrieved 15 July 2010.

- ^ "Harrold Brothers". City of Adelaide – the Splendid Clipper Ship. CSCOAL. Retrieved 15 July 2010.

- ^ "Henry Martin". City of Adelaide – the Splendid Clipper Ship. CSCOAL. Retrieved 15 July 2010.

- ^ "1/4 Million Descendants". City of Adelaide – the Splendid Clipper Ship. CSCOAL. Archived from the original on 21 February 2009. Retrieved 15 July 2010.

- ^ "Diary Transcripts". City of Adelaide – the Splendid Clipper Ship. CSCOAL. Retrieved 15 July 2010.

- ^ Lubbock 1991, p. 155.

- ^ a b "Diary of James Anderson McLauchlan". City of Adelaide – the Splendid Clipper Ship. CSCOAL. Retrieved 15 July 2010.

- ^ "Tuesday, September 8, 1874". The Argus. Melbourne. 8 September 1874. p. 5. Retrieved 21 May 2011 – via Trove.

- ^ "VIII.—Agricultural". The South Australian Advertiser. Adelaide. 10 September 1874. p. 5. Retrieved 21 May 2011 – via Trove.

- ^ "Diary of Frederick Bullock". City of Adelaide – the Splendid Clipper Ship. CSCOAL. Archived from the original on 5 May 2013. Retrieved 3 April 2012.

- ^ Tim Ball, "Timber!", Beaver, April 987, Vol. 67#2 pp. 45–56

- ^ "Welcome to the Adelaide Health Centre" (Press release). National Health Service. 30 June 2009. Retrieved 15 July 2010.

- ^ a b c "Account of Maree Moore". City of Adelaide – the Splendid Clipper Ship. CSCOAL. Retrieved 15 July 2010.

- ^ "Renaming Ceremony – Greenwich – 18 October 2013". City of Adelaide – the Splendid Clipper Ship. CSCOAL. Retrieved 21 November 2013.

- ^ "Death of Carrick club's commodore". The Herald (Glasgow). 22 December 1989. Retrieved 13 February 2015.

- ^ a b "City of Adelaide". Scottish Maritime Museum. Archived from the original on 30 July 2010. Retrieved 15 July 2010.

- ^ "City of Adelaide clipper handed to Australian owners". BBC News. 6 September 2013. Retrieved 8 September 2013.

- ^ "1992–2001 Scottish Maritime Museum". City of Adelaide – the Splendid Clipper Ship. CSCOAL. Retrieved 15 July 2010.

- ^ a b c DTZ in association with Sir Neil Cossons (2 September 2010). "Options Appraisal – The City of Adelaide" (PDF). Historic Scotland.

- ^ a b "Demolition of clipper ship "Carrick" – "City of Adelaide"". North Ayrshire Council. Retrieved 15 November 2013.

- ^ "Demolition of clipper ship 'Carrick' – City of Adelaide". North Ayrshire Council. 26 February 2001. Archived from the original on 12 May 2011. Retrieved 15 July 2010.

- ^ "2001 Conference". City of Adelaide – the Splendid Clipper Ship. CSCOAL. Retrieved 15 July 2010.

- ^ "Mike Edwards Proposal". City of Adelaide – the Splendid Clipper Ship. CSCOAL. Retrieved 15 November 2012.

- ^ "Final Departure of World's Oldest Clipper Ship from Scotland – 20 September 2013". City of Adelaide – the Splendid Clipper Ship. CSCOAL. Retrieved 22 November 2013.

- ^ "Deconstruction of the clipper ship 'Carrick – City of Adelaide'". North Ayrshire Council. 10 May 2006. Retrieved 14 November 2013.

- ^ a b c "British PM Petitioned to Save 'City of Adelaide'". City of Adelaide – the Splendid Clipper Ship. CSCOAL. 16 March 2009. Retrieved 15 July 2010.

- ^ "Application to Demolish". City of Adelaide – the Splendid Clipper Ship. CSCOAL. Retrieved 20 November 2012.

- ^ "Call to rethink clipper's future". BBC News. 21 May 2007.

- ^ "Adelaide may rise from the ashes". The Advertiser. Adelaide. 22 May 2007.

- ^ "Fresh bid to save historic ship". BBC News. 20 July 2007.

- ^ "Museum of Australian Democracy". City of Adelaide – the Splendid Clipper Ship. CSCOAL. Retrieved 14 November 2013.

- ^ "Australian Open Letter plea to UK Prime Minister to not destroy City of Adelaide". City of Adelaide – the Splendid Clipper Ship. CSCOAL. Retrieved 15 July 2010.

- ^ "Lack of water ends ship protest". BBC News. 16 October 2009.

- ^ "Campaign to save City of Adelaide". City of Adelaide – the Splendid Clipper Ship. CSCOAL. 19 November 2009.

- ^ Noakes, Gary (1 February 2010). "Disposing of Ship Could Bankrupt Scots Museum". Museums Journal (110/02). Museums Association: 5.

- ^ "HLF Funding not viable for UK Solution". City of Adelaide – the Splendid Clipper Ship. CSCOAL. 16 December 2009.

- ^ "Minister considers options for the SV Carrick" (Press release). Historic Scotland. 5 March 2010. Retrieved 20 November 2013.

- ^ a b "Culture Minister announces plan to save City of Adelaide/Carrick with Australian bidder". Historic Scotland. 28 August 2010.

- ^ "Historic Scotland appoints DTZ to undertake options appraisal for Carrick" (Press release). Historic Scotland. 28 April 2010. Retrieved 15 July 2010.

- ^ "Carrick diary reveals fascinating legacy". Irvine Herald. 21 May 2010.

- ^ "Prince Philip reflects on revival of SS Great Britain". BBC News. 4 July 2010.

- ^ Castello, Renato (30 August 2010). "Famed clipper Adelaide finally coming home from Scotland". The Advertiser.

- ^ "Blow to bid to bring 1864 ship home to Sunderland". BBC News. 29 August 2010.

- ^ a b c d e "Transportation". City of Adelaide – the Splendid Clipper Ship. CSCOAL. Retrieved 14 November 2013.

- ^ "City of Adelaide, Irvine: Laser Scanning". Headland Archaeology. Archived from the original on 5 October 2013. Retrieved 23 May 2012.

- ^ "Virtual Tours". City of Adelaide – the Splendid Clipper Ship. CSCOAL. Retrieved 23 May 2012.

- ^ McGowan, Eric (10 December 2010). "Carrick gets ship-shape for Oz voyage". Irvine Herald. Retrieved 17 December 2010.

- ^ McGowan, Eric (13 January 2012). "Carrick ready for the off". Irvine Herald. Retrieved 14 March 2012.

- ^ "City of Adelaide clipper ship occupied by campaigner". BBC News. 27 February 2012. Retrieved 14 March 2012.

- ^ "Rudder Arrives – 17 December 2012". City of Adelaide – the Splendid Clipper Ship. CSCOAL. 17 December 2012.

- ^ "The Rudder". City of Adelaide – the Splendid Clipper Ship. CSCOAL. 28 February 2008.

- ^ "Work starts in Scotland – 9 April 2013". City of Adelaide – the Splendid Clipper Ship. CSCOAL. 9 April 2013.

- ^ "Historic clipper City of Adelaide 'floats again' for first time since 1991". BBC News. 8 September 2013. Retrieved 8 September 2013.

- ^ City of Adelaide arrives at Chatham – 25 September 2013 CSCOAL press release. Retrieved 3 October 2013.

- ^ "Historic City of Adelaide clipper ship journey home to SA in limbo over heritage assessment". Herald Sun. 30 September 2013.

- ^ a b "Prince Philip renames Sunderland's historic Adelaide clipper ahead of trip Down Under". Sunderland Echo. 19 October 2013. Archived from the original on 22 October 2013. Retrieved 20 November 2013.

- ^ "Federal Government confirms it will provide $850,000 for the City of Adelaide clipper ship's journey to Largs North". Portside Messenger. 17 October 2013. Retrieved 21 November 2013.

- ^ "Dordrecht Arrival". City of Adelaide – the Splendid Clipper Ship. CSCOAL. 24 October 2013.

- ^ "Three, Two, One, Lift-off". City of Adelaide – the Splendid Clipper Ship. CSCOAL. 22 November 2013.

- ^ "Last Voyage Underway". City of Adelaide – the Splendid Clipper Ship. CSCOAL. 26 November 2013.

- ^ a b c d e f g "Final Voyage". City of Adelaide: The Splendid Clipper Ship. Clipper Ship 'City of Adelaide'. Retrieved 14 December 2013.

- ^ "City of Adelaide clipper ship leaves Netherlands on final journey to South Australia". News. AU. 22 November 2013. Retrieved 11 December 2013.

- ^ "19th-century clipper ship in Norfolk". Wavy. 11 December 2013. Archived from the original on 12 December 2013. Retrieved 11 December 2013.

- ^ a b c "City of Adelaide clipper ship finally arrives home in Adelaide", The Advertiser, 3 February 2014, retrieved 3 February 2014.

- ^ "City of Adelaide Preservation Trust calls for more donations as the clipper hits Port Hedland in Western Australia", The Advertiser, 24 January 2014, retrieved 3 February 2014.

- ^ "Fletcher's Slip firming up as likely permanent home for City of Adelaide clipper ship", Portside Messenger, 30 January 2014, retrieved 3 February 2014.

- ^ "New time of arrival for City of Adelaide at temporary home in Dock One at Port Adelaide", The Advertiser, 5 February 2014, retrieved 6 February 2014.

- ^ "City of Adelaide clipper finally finds safe harbour", The Advertiser, 6 February 2014, retrieved 7 February 2014.

- ^ City of Adelaide clipper celebrates 150th anniversary at Port Adelaide Portside Messenger, 17 May 2014. Retrieved 17 May 2014.

- ^ Clipper Ship 'City of Adelaide' Ltd. > 150th Birthday Community Event Archived 8 May 2014 at the Wayback Machine Accessed 13 May 2014.

- ^ One step closer in preserving the unique maritime heritage of the Port Renewal SA, 5 April 2017. Retrieved 4 August 2017.

- ^ City of Adelaide ship deadline approaches, Buffalo replica to be demolished ABC News, 30 January 2019. Retrieved 9 March 2019.

- ^ Great-grandaughter of Clipper ship’s first captain makes five figure donation Portside Messenger, 3 August 2017. Retrieved 4 July 2017.

- ^ The Port’s historic clipper ship is on the move Portside Weekly Messenger, 10 January 2018. Retrieved 7 February 2018.

- ^ New City of Adelaide clipper ship children’s book opens maritime history to new audience Portside Messenger, 15 March 2018. Retrieved 7 May 2018

- ^ "News". Clipper Ship 'City of Adelaide'. Clipper Ship City of Adelaide Ltd. Retrieved 11 December 2019.

- ^ City of Adelaide clipper makes its final voyage after returning from Scotland ABC News, 29 November 2019. Retrieved 17 December 2019.

External links

- City of Adelaide- Sunderland Maritime Heritage

- Clipper Ship City of Adelaide Ltd (CSCOAL)

- City of Adelaide Wiki

- Friends of City of Adelaide Accessed 29 January 2014.

- BBC story of decision to scrap

- Museum of Australian Democracy – Old Parliament House Canberra at the Library of Congress Web Archives (archived 2009-05-15)

- "The Future of the S.V. Carrick", History Scotland magazine at the Wayback Machine (archived 2006-02-08)

- Traditional Boats and Tall Ships magazine article

- World Ship Trust page

- 1864 in England

- 1864 ships

- Ships built on the River Wear

- Clippers

- Full-rigged ships

- Individual sailing vessels

- Maritime incidents in August 1874

- Merchant ships of the United Kingdom

- Tall ships of the United Kingdom

- Museum ships in Australia

- Museums in Adelaide

- Ships of South Australia

- Ships and vessels on the National Archive of Historic Vessels

- Transport museums in South Australia