Nintendo 64

| |

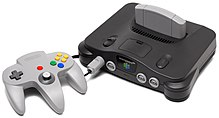

A black Nintendo 64 (right) and light gray Nintendo 64 controller | |

| Also known as |

|

|---|---|

| Developer | Nintendo IRD |

| Manufacturer | Nintendo |

| Type | Home video game console |

| Generation | Fifth |

| Release date | |

| Lifespan | 1996-2002 (6 years) |

| Discontinued |

|

| Units sold |

|

| Media |

|

| CPU | 64-bit NEC VR4300 @ 93.75 MHz |

| Memory | 4 MB Rambus RDRAM (8 MB with Expansion Pak) |

| Storage | 4–64 MB Game Pak |

| Removable storage | 32 KB Controller Pak |

| Graphics | SGI RCP @ 62.5 MHz |

| Sound | 16-bit, 48 or 44.1 kHz stereo |

| Controller input | Nintendo 64 controller |

| Power | Switching power supply, 12 V and 3.3 V DC |

| Online services |

|

| Dimensions | 2.87 in × 10.23 in × 7.48 in (72.9 mm × 259.8 mm × 190.0 mm) |

| Mass | 2.42 lb (1.10 kg) |

| Best-selling game | Super Mario 64, 11.62 million (as of May 21, 2003)[8] |

| Predecessor | Super NES |

| Successor | GameCube |

| Related | Nintendo 64DD |

The Nintendo 64[a] (N64) is a home video game console developed and marketed by Nintendo. It was released in Japan on June 23, 1996, in North America on September 29, 1996, and in Europe and Australia on March 1, 1997 . The successor to the Super Nintendo Entertainment System, it was the last major home console to use cartridges as its primary storage format until the Nintendo Switch in 2017.[9] As a fifth-generation console, the Nintendo 64 primarily competed with the Sony PlayStation and the Sega Saturn.

Development began in 1993 in partnership with Silicon Graphics, using the codename Project Reality, then a test model and arcade platform called Ultra 64. The final design was named after its 64-bit CPU, which aided in the console's 3D capabilities. Its design was mostly complete by mid-1995 and launch was delayed until 1996 for the completion of the launch games Super Mario 64, Pilotwings 64, and Saikyō Habu Shōgi (exclusive to Japan).

The charcoal-gray console was followed by a series of color variants. Some games require the Expansion Pak accessory to increase system RAM from 4 MB to 8 MB, for improved graphics and functionality. The console mainly supports saved game storage either onboard cartridges or on the Controller Pak accessory. The 64DD peripheral drive hosts both exclusive games and expansion content for cartridges, with many further accessories plus the defunct Internet service Randnet, but it was a commercial failure and was released only in Japan.

Time named it Machine of the Year in 1996,[10] and in 2011, IGN named it the ninth-greatest video game console of all time.[11] The Nintendo 64 was discontinued in 2002 following the 2001 launch of its successor, the GameCube. The Nintendo 64 was critically acclaimed and remains one of the most recognized video game consoles.

History[edit]

Background[edit]

"At the heart of the [Project Reality] system will be a version of the MIPS(r) Multimedia Engine, a chip-set consisting of a 64-bit MIPS RISC microprocessor, a graphics co-processor chip and Application Specific Integrated Circuits (ASICs)". "The product, which will be developed specifically for Nintendo, will be unveiled in arcades in 1994, and will be available for home use by late 1995. The target U.S. price for the home system is below $250". "For the first time, leading-edge MIPS RISC microprocessor technology will be used in the video entertainment industry [and already] powers computers ranging from PCs to supercomputers".

—SGI press release, August 23, 1993[12]

Following the video game crash of 1983, Nintendo led the industry with its first home game console, the Famicom, originally released in Japan in 1983 and later released internationally as the Nintendo Entertainment System (NES) beginning in 1985. Though the NES and its successor, the Super Nintendo Entertainment System (SNES), were commercially successful, sales for the SNES decreased as a result of the Japanese recession. Competition from emerging rival Sega's 32-bit Saturn console over Nintendo's 16-bit SNES emphasized Nintendo's need to develop improved SNES hardware or risk losing market dominance to its competitors. The Atari 5200, 7800, Lynx, and Jaguar also competed with Nintendo during this time.

Nintendo sought to enhance the SNES with a proposed CD-ROM peripheral, to be developed in partnership with other companies. Contracts with CD-ROM technology pioneers Philips and Sony failed after some hardware prototypes, and no games from Nintendo or other interested third parties were developed. Philips used the software portion of its license by releasing original Mario and Zelda games on its competing CD-i console, and Sony salvaged its internal progress to develop the PlayStation. Nintendo's third-party developers protested its strict licensing policies.[13]

Development[edit]

Silicon Graphics, Inc. (SGI), a long-time leader in graphics computing, was exploring expansion by adapting its supercomputing technology into the higher volume consumer market, starting with the video game market. SGI reduced its MIPS R4000 family of enterprise CPUs, to consume only 0.5 watts of power instead of 1.5 to 2 watts, with an estimated target price of US$40 instead of US$80–200.[14] The company created a design proposal for a video game chipset, seeking an established partner in that market. Jim Clark, founder of SGI, offered the proposal to Tom Kalinske, who was the CEO of Sega of America. The next candidate would be Nintendo.[15]

Kalinske said that he and Joe Miller of Sega of America were "quite impressed" with SGI's prototype, and invited their hardware team to travel from Japan to meet with SGI. The engineers from Sega Enterprises said that their evaluation of the early prototype had revealed several hardware problems. Those were subsequently resolved, but Sega had already decided against SGI's design.[15] Nintendo disputed this account, arguing that SGI chose Nintendo because Nintendo was the more appealing partner. Sega demanded exclusive rights to the chip, but Nintendo offered a non-exclusive license.[13] Michael Slater, publisher of Microprocessor Report said, "The mere fact of a business relationship there is significant because of Nintendo's phenomenal ability to drive volume. If it works at all, it could bring MIPS to levels of volume [SGI] never dreamed of."[14]

Jim Clark met with the CEO of Nintendo at the time, Hiroshi Yamauchi, in early 1993, initiating Project Reality.[13] On August 23, 1993, the companies announced a global joint development and licensing agreement surrounding Project Reality,[16][12] projecting that the yet unnamed product would be "developed specifically for Nintendo, would be unveiled in arcades in 1994, and would be available for home use by late 1995 ... below $250".[12] This announcement coincided with Nintendo's August 1993 Shoshinkai trade show.[17][12]

SGI had named the core components Reality Immersion Technology, which would be first used in Project Reality: the MIPS R4300i CPU, the MIPS Reality Coprocessor, and the embedded software.[12][16][18] Some chip technology and manufacturing was provided by NEC, Toshiba, and Sharp.[19] SGI had recently acquired MIPS Computer Systems (renamed to MIPS Technologies), and the two worked together to be ultimately responsible for the design of the Reality Immersion Technology chips[12] under engineering director Jim Foran[20][21] and chief hardware architect Tim Van Hook.[22]

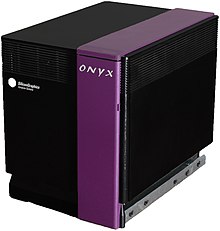

The initial Project Reality game development platform was developed and sold by SGI in the form of its Onyx supercomputer costing US$100,000[23]–US$250,000 (equivalent to $513,920 in 2023)[24][22] and loaded with the namesake US$50,000[25] RealityEngine2 graphics boards and four 150 MHz R4400 CPUs.[23] Its software includes early Project Reality application and emulation APIs based on Performer and OpenGL. This graphics supercomputing platform had served as the source design which SGI had reduced down to become the Reality Immersion Technology for Project Reality.[26][22]

The Project Reality team prototyped a game controller for the development system by modifying a Super NES controller to have a primitive analog joystick and Z trigger. Under maximal secrecy even from the rest of the company, a LucasArts developer said his team would "furtively hide the prototype controller in a cardboard box while we used it. In answer to the inevitable questions about what we were doing, we replied jokingly that it was a new type of controller—a bowl of liquid that absorbed your thoughts through your fingertips. Of course, you had to think in Japanese..."[22]

On June 23, 1994, Nintendo announced the official name of the still unfinished console as "Ultra 64". The first group of elite developers selected by Nintendo was nicknamed the "Dream Team": Silicon Graphics, Inc.; Alias Research, Inc.; Software Creations; Rambus, Inc.; MultiGen, Inc.; Rare, Ltd. and Rare Coin-It Toys & Games, Inc.; WMS Industries, Inc.; Acclaim Entertainment, Inc.; Williams Entertainment, Inc.; Paradigm Simulation, Inc.; Spectrum Holobyte; DMA Design Ltd.; Angel Studios;[27][28]: 20 Ocean; Time Warner Interactive;[29] and Mindscape.[30]

By purchasing and developing upon Project Reality's graphics supercomputing platform, Nintendo and its Dream Team could begin prototyping their games according to SGI's estimated console performance profile, prior to the finalization of the console hardware specifications. When the Ultra 64 hardware was finalized, that supercomputer-based prototyping platform was later supplanted by a much cheaper and fully accurate console simulation board to be hosted within a low-end SGI Indy workstation in July 1995.[12] SGI's early performance estimates based upon its supercomputing platform were ultimately reported to have been fairly accurate to the final Ultra 64 product,[28]: 26 allowing LucasArts developers to port their Star Wars game prototype to console reference hardware in only three days.[22]

The console's design was publicly revealed for the first time in late Q2 1994. Images of the console displayed the Nintendo Ultra 64 logo and a ROM cartridge, but no controller. This prototype console's form factor would be retained by the product when it eventually launched. Having initially indicated the possibility of utilising the increasingly popular CD-ROM if the medium's endemic performance problems were solved,[31][32]: 77 the company now announced a much faster but space-limited cartridge-based system, which prompted open analysis by the gaming press. The system was frequently marketed as the world's first 64-bit gaming system, often stating the console was more powerful than the first Moon landing computers.[33] Atari had already claimed to have made the first 64-bit game console with their Atari Jaguar,[34] but the Jaguar only uses a general 64-bit architecture in conjunction with two 32-bit RISC processors and a 16/32-bit Motorola 68000.[35]

Later in Q2 1994, Nintendo signed a licensing agreement with Midway's parent company which enabled Midway to develop and market arcade games with the Ultra 64 brand, and formed a joint venture company called "Williams/Nintendo" to market Nintendo-exclusive home conversions of these games.[36] The result is two Ultra 64 branded arcade games, Killer Instinct and Cruis'n USA.[37] Not derived from Project Reality's console-based branch of Ultra 64, the arcade branch uses a different MIPS CPU, has no Reality Coprocessor, and uses onboard ROM chips and a hard drive instead of a cartridge.[37][38] Killer Instinct features 3D character artwork pre-rendered into 2D form, and computer-generated movie backgrounds that are streamed off the hard drive[39] and animated as the characters move horizontally.

Previously, the plan had been to release the console with the name "Ultra Famicom" in Japan and "Nintendo Ultra 64" in other markets.[40][41] Rumors circulated attributing the name change to the possibility of legal action by Konami's ownership of the Ultra Games trademark. Nintendo said that trademark issues were not a factor, and the sole reason for any name change was to establish a single worldwide brand and logo for the console.[42] The new global name "Nintendo 64" was proposed by Earthbound series developer Shigesato Itoi.[43][44] The prefix for the model numbering scheme for hardware and software across the Nintendo 64 platform is "NUS-", a reference to the console's original name of "Nintendo Ultra Sixty-four".[45]

Announcement[edit]

The newly renamed Nintendo 64 console was unveiled to the public in playable form on November 24, 1995, at Nintendo's 7th Annual Shoshinkai trade show. Eager for a preview, "hordes of Japanese schoolkids huddled in the cold outside ... the electricity of anticipation clearly rippling through their ranks".[26] Game Zero magazine disseminated photos of the event two days later.[46] Official coverage by Nintendo followed later via the Nintendo Power website and print magazine.

The console was originally slated for release by Christmas of 1995. In May 1995, Nintendo delayed the release to April 21, 1996.[10][26][46] Consumers anticipating a Nintendo release the following year at a lower price than the competition reportedly reduced the sales of competing Sega and Sony consoles during the important Christmas shopping season.[47]: 24 Electronic Gaming Monthly editor Ed Semrad even suggested that Nintendo may have announced the April 21, 1996 release date with this end in mind, knowing in advance that the system would not be ready by that date.[48]

In its explanation of the delay, Nintendo claimed it needed more time for Nintendo 64 software to mature,[13] and for third-party developers to produce games.[10][49] Adrian Sfarti, a former engineer for SGI, attributed the delay to hardware problems; he claimed that the chips underperformed in testing and were being redesigned.[13] In 1996, the Nintendo 64's software development kit was completely redesigned as the Windows-based Partner-N64 system, by Kyoto Microcomputer, Co. Ltd. of Japan.[50][51]

The Nintendo 64's release date was later delayed again, to June 23, 1996. Nintendo said the reason for this delay, and in particular, the cancellation of plans to release the console in all markets worldwide simultaneously, was that the company's marketing studies now indicated that they would not be able to manufacture enough units to meet demand by April 21, 1996, potentially angering retailers in the same way Sega had done with its surprise early launch of the Saturn in North America and Europe.[52]

To counteract the possibility that gamers would grow impatient with the wait for the Nintendo 64 and purchase one of the several competing consoles already on the market, Nintendo ran ads for the system well in advance of its announced release dates, with slogans like "Wait for it..." and "Is it worth the wait? Only if you want the best!"[53]

Release[edit]

Popular Electronics called the launch a "much hyped, long-anticipated moment".[47] Several months before the launch, GamePro reported that many gamers, including a large percentage of their own editorial staff, were already saying they favored the Nintendo 64 over the Saturn and PlayStation.[54]

The console was first released in Japan on June 23, 1996.[3] Though the initial shipment of 300,000 units sold out on the first day, Nintendo successfully avoided a repeat of the Super Famicom launch day pandemonium, in part by using a wider retail network which included convenience stores.[55] The remaining 200,000 units of the first production run shipped on June 26 and 30, with almost all of them reserved ahead of time.[56] In the months between the Japanese and North American launches, the Nintendo 64 saw brisk sales on the American gray market, with import stores charging as much as $699 plus shipping for the system.[57] The Nintendo 64 was first sold in North America on September 26, 1996, though having been advertised for the 29th.[58][59] It was launched with just two games in the United States, Pilotwings 64 and Super Mario 64; Cruis'n USA was pulled from the line-up less than a month before launch because it did not meet Nintendo's quality standards.[60] In 1994, prior to the launch, Nintendo of America chairman Howard Lincoln emphasized the quality of first-party games, saying "... we're convinced that a few great games at launch are more important than great games mixed in with a lot of dogs".[32]: 77 The PAL version of the console was released in Europe on March 1, 1997, except for France where it was released on September 1 of the same year.[4][61] According to Nintendo of America representatives, Nintendo had been planning a simultaneous launch in Japan, North America, and Europe, but market studies indicated that worldwide demand for the system far exceeded the number of units they could have ready by launch, potentially leading to consumer and retailer frustration.[62]

Originally intended to be priced at US$250,[10] the console was ultimately launched at US$199.99 to make it competitive with Sony and Sega offerings, as both the Saturn and PlayStation had been lowered to $199.99 earlier that summer.[63][64] Nintendo priced the console as an impulse purchase, a strategy from the toy industry.[65] The price of the console in the United States was further reduced in August 1998.[66]

Promotion[edit]

The Nintendo 64's North American launch was backed with a $54 million marketing campaign by Leo Burnett Worldwide (meaning over $100 in marketing per North American unit that had been manufactured up to this point).[67] While the competing Saturn and PlayStation both set teenagers and adults as their target audience, the Nintendo 64's target audience was pre-teens.[68]

To boost sales during the slow post-Christmas season, Nintendo and General Mills worked together on a promotional campaign that appeared in early 1999. The advertisement by Saatchi and Saatchi, New York began on January 25 and encouraged children to buy Fruit by the Foot snacks for tips to help them with their Nintendo 64 games. Ninety different tips were available, with three variations of thirty tips each.[69]

Nintendo advertised its Funtastic Series of peripherals with a $10 million print and television campaign from February 28 to April 30, 2000. Leo Burnett Worldwide was in charge again.[70]

Hardware[edit]

Technical specifications[edit]

|

|

|

| VR4300 CPU | 2-chip RDRAM | 64-bit "Reality Coprocessor" |

|

|

|

| NEC VR4300 | Motherboard (bottom) | Motherboard (top) |

The console's main microprocessor is a 64-bit NEC VR4300 CPU with a clock rate of 93.75 MHz and a performance of 125 MIPS.[71] Popular Electronics said it had power similar to the Pentium processors found in desktop computers.[47] Except for its narrower 32-bit system bus, the VR4300 retained the computational abilities of the more powerful 64-bit MIPS R4300i,[71] though software rarely took advantage of 64-bit data precision operations. Nintendo 64 games generally used faster and more compact 32-bit data-operations,[72] as these were sufficient to generate 3D-scene data for the console's RSP (Reality Signal Processor) unit. In addition, 32-bit code executes faster and requires less storage space (which is at a premium on the Nintendo 64's cartridges).

In terms of its random-access memory (RAM), the Nintendo 64 was one of the first consoles to implement a unified memory subsystem, instead of having separate banks of memory for CPU, audio, and video operations.[73] The memory itself consists of 4 megabytes of Rambus RDRAM, expandable to 8 MB with the Expansion Pak. Rambus was quite new at the time and offered Nintendo a way to provide a large amount of bandwidth for a relatively low cost.

Audio may be processed by the Reality Coprocessor or the CPU and is output to a DAC with up to 48.0 kHz sample rate.[74]

The system allows for video output in two formats: composite video[75] and S-Video. The composite and S-Video cables are the same as those used with the preceding Super NES and succeeding GameCube platforms.

The Nintendo 64 supports 16.8 million colors.[76] The system can display resolutions from 320×240 up to 640×480 pixels. Most games that make use of the system's higher resolution mode require use of the Expansion Pak RAM upgrade; though several do not,[77] such as Acclaim's NFL Quarterback Club series and EA Sports's second generation Madden, FIFA, Supercross, and NHL games. The majority of games use the system's low resolution 320×240 mode.[77] Many games support a video display ratio of up to 16:9 using either anamorphic widescreen or letterboxing.

Controller[edit]

The Nintendo 64 controller has an "M" shape with 10 buttons, one analog control stick, and a directional pad.

The Nintendo 64 is one of the first with four controller ports. According to Shigeru Miyamoto, Nintendo opted to have four controller ports for its first console powerful enough to handle a four player split screen without significant slowdown.[78]

Game Paks[edit]

After Nintendo's multiple plans for compact disc-based games for Super NES, the industry expected its next console to, like PlayStation, use that medium. The first Nintendo 64 prototypes in November 1995 surprised observers by again using ROM cartridge.[79] Cartridge size varies[80] from 4 to 64 MB. Many cartridges include the ability to save games internally.

Nintendo's controversial selection of the cartridge medium for the Nintendo 64 has been cited as a key factor in the company losing its dominant position in the gaming market. Some of the cartridge's advantages are difficult for developers to manifest prominently,[81][82][83] requiring innovative solutions which only came late in the console's life cycle.[84][85][86]

Advantages[edit]

Nintendo cited several advantages for making the Nintendo 64 cartridge-based,[87] primarily cartridges' very fast load times in comparison to compact disc-based games. Being able to play a cartridge game almost immediately had helped Nintendo defeat the Commodore 64 and other US home computers in the 1980s.[79] While loading screens appear in many PlayStation games, they are rare in Nintendo 64 games. Although vulnerable to long-term environmental damage,[87] the cartridges are far more resistant to physical damage than compact discs. Nintendo also cited the fact that cartridges are more difficult to pirate than CDs, thus resisting copyright infringement, albeit at the expense of lowered profit margin for Nintendo.[88] While unauthorized N64 interface devices for the PC were later developed, these devices are rare when compared to a regular CD drive used on the PlayStation, which suffered widespread copyright infringement.[89][90]

The big strength was the N64 cartridge. We use the cartridge almost like normal RAM and are streaming all level data, textures, animations, music, sound and even program code while the game is running. With the final size of the levels and the amount of textures, the RAM of the N64 never would have been even remotely enough to fit any individual level. So the cartridge technology really saved the day.

Factor 5, Bringing Indy to N64 at IGN[84]

Disadvantages[edit]

On the downside, cartridges took longer to manufacture than CDs, with each production run (from order to delivery) taking two weeks or more.[91][79] This meant that publishers of Nintendo 64 games had to predict demand for a game ahead of its release. They risked being left with a surplus of expensive cartridges for a failed game, or a weeks-long shortage of product if they underestimated a game's popularity.[91] The cost of producing a Nintendo 64 cartridge was also far higher than for a CD.[74][79] Publishers passed these expenses onto the consumer. Nintendo 64 games cost an average of $10 more when compared to games produced for rival consoles.[92] The higher cost also created the potential for much greater losses to the game's publisher in the case of a flop, making the less risky CD medium tempting for third-party companies.[93] Some third-party companies also complained that they were at an unfair disadvantage against Nintendo first-party developers when publishing games for the Nintendo 64, since Nintendo owned the manufacturing plant where cartridges for their consoles are made and therefore could sell their first party games at a lower price,[67] and prioritize their production over those of other companies.[79]

Perhaps the most important reason for cartridge, observers thought, was what a later writer described as "Nintendo’s congenital need to be different, and to assert its idiosyncratic hegemony by making everyone else dance to its tune while it was at it".[79]

As fifth generation games became more complex in content, sound and graphics, games began to exceed the limits of cartridge storage capacity. Nintendo 64 cartridges had a maximum of 64 MB of data,[81] whereas CDs held 650 MB.[94][82] The Los Angeles Times initially defended the quality control incentives associated with working with limited storage on cartridges, citing Nintendo's position that cartridge game developers tend to "place a premium on substance over flash", and noted that the N64 launch games are free of "poorly acted live-action sequences or half-baked musical overtures" which it says tend to be found on CD-ROM games.[95] However, the cartridge's limitations became apparent with software ported from other consoles, so Nintendo 64 versions of cross-platform games were truncated or redesigned with the storage limits of a cartridge in mind.[96] For instance this meant fewer textures, and/or shorter music tracks, while full motion video was not usually feasible for use in cutscenes unless heavily compressed and of very brief length.[67] Another of its technical drawbacks is a limited-size texture cache, which force textures of limited dimensions and reduced color depth, appearing stretched when covering in-game surfaces.

The era's competing systems from Sony and Sega (the PlayStation and Saturn, respectively) used CD-ROM discs to store their games.[97] As a result, game developers who had traditionally supported Nintendo game consoles were now developing games for the competition.[97] Some third-party developers, such as Square and Enix, whose Final Fantasy VII and Dragon Warrior VII were initially planned for the Nintendo 64,[98] switched to the PlayStation, citing the insufficient storage capacity of the N64 cartridges.[99] Some who remained released fewer games to the Nintendo 64; Konami released fifty PlayStation games, but only twenty nine for the Nintendo 64. New Nintendo 64 game releases were infrequent while new games were coming out rapidly for the PlayStation.[83]

Through the difficulties with third parties, the Nintendo 64 supported popular games such as GoldenEye 007, giving it a long market life. Additionally, Nintendo's strong first-party franchises[100] such as Mario had strong name brand appeal. Second-parties of Nintendo, such as Rare, helped.[83]

Color variants[edit]

The Nintendo 64 comes in several colors. The standard Nintendo 64 is dark gray, nearly black,[101] and the controller is light gray (later releases in the U.S., Canada, and Australia included a bonus second controller in Atomic Purple). Various colorations and special editions were released.

Most Nintendo 64 game cartridges are gray in color, but some games have a colored cartridge.[102] Fourteen games have black cartridges, and other colors (such as yellow, blue, red, gold, and green) were each used for six or fewer games. Several games, such as The Legend of Zelda: Ocarina of Time, were released both in standard gray and in colored, limited edition versions.[103]

Programming characteristics[edit]

The programming characteristics of the Nintendo 64 present unique challenges, with distinct potential advantages. The Economist described effective programming for the Nintendo 64 as being "horrendously complex".[104] As with many other game consoles and other types of embedded systems, the Nintendo 64's architectural optimizations are uniquely acute, due to a combination of oversight on the part of the hardware designers, limitations on 3D technology of the time, and manufacturing capabilities.

As the Nintendo 64 reached the end of its lifecycle, hardware development chief Genyo Takeda repeatedly referred to the programming challenges using the word hansei (反省, 'reflective regret'). Looking back, Takeda said "When we made Nintendo 64, we thought it was logical that if you want to make advanced games, it becomes technically more difficult. We were wrong. We now understand it's the cruising speed that matters, not the momentary flash of peak power."[105]

Regional lock-out[edit]

In contrast to the NES and the Super NES—with unique names and hardware designs in Japan—Nintendo developed the same brand and hardware design for the Nintendo 64 in every region worldwide. The company initially stated that regional lock-out chips would be the chief distinction to localize games.[106] Following the North American launch, it stated that regional lock-out is enforced by unique notches in the back of cartridges instead of chips.[107]

Games[edit]

A total of 388 Nintendo 64 games were officially released, with just 85 exclusively sold in Japan. For comparison, the PlayStation received 7,918 games, the Saturn got over 1,000, the SNES got 1,755 games, and the NES got 716 Western releases plus over 1,000 in Japan. The considerably smaller Nintendo 64 game library has been attributed by some to the controversial decision not to adopt the CD-ROM, and programming difficulties for its complex architecture.[97] This trend is also seen as a result of Hiroshi Yamauchi's strategy, announced during his speech at the Nintendo 64's November 1995 unveiling, that Nintendo would be restricting the number of games produced for the Nintendo 64 so that developers would focus on higher quality instead of quantity.[94] The Los Angeles Times also observed that this was part of Nintendo's "penchant for perfection [...] while other platforms offer quite a bit of junk, Nintendo routinely orders game developers back to the boards to fix less-than-perfect titles".[95]

Although having less third-party support than rival consoles, Nintendo's strong first-party franchises[100] such as Mario enjoyed wide brand appeal. Second-parties of Nintendo, such as Rare, released groundbreaking titles.[83] Consequently, the Nintendo 64 game library included a high number of critically acclaimed and widely sold games.[108] According to TRSTS reports, three of the top five best-selling games in the U.S. for December 1996 were Nintendo 64 games (both of the remaining two were Super NES games).[109] Super Mario 64 is the best-selling console game of the generation, with 11 million units sold[110] beating Gran Turismo for the PlayStation (at 10.85 million[111]) and Final Fantasy VII (at 9.72 million[112]) in sales. The game also received much praise from critics and helped to pioneer three-dimensional control schemes. GoldenEye 007 was important in the evolution of the first-person shooter, and has been named one of the greatest in the genre.[113] The Legend of Zelda: Ocarina of Time set the standard for future 3D action-adventure games[114] and is considered by many to be one of the greatest games ever made.[114][115][116]

Graphics[edit]

The most graphically demanding Nintendo 64 games on larger 32 or 64 MB cartridges are among the most advanced and detailed of 32- and 64-bit platforms. To maximize the hardware, developers created custom microcode. Nintendo 64 games running on custom microcode benefit from much higher polygon counts and more advanced lighting, animation, physics, and AI routines than its competition. Conker's Bad Fur Day is arguably the pinnacle of its generation combining multicolored real-time lighting that illuminates each area to real-time shadowing, and detailed texturing replete with a full in-game facial animation system. The Nintendo 64 is capable of executing many more advanced and complex rendering techniques than its competitors. It is the first home console to feature trilinear filtering,[117] to smooth textures. This contrasts with the Saturn and PlayStation, which use nearest-neighbor interpolation[118] and produce more pixelated textures. Overall however the results of the Nintendo cartridge system were mixed.

The smaller storage size of ROM cartridges can limit the number of available textures. As a result, many games with much smaller 8 or 12 MB cartridges are forced to stretch textures over larger surfaces. Compounded by a limit of 4,096 bytes[119] of on-chip texture memory, the result is often a distorted, out-of-proportion appearance. Many games with larger 32 or 64 MB cartridges avoid this issue entirely, including Resident Evil 2, Sin and Punishment: Successor of the Earth, and Conker's Bad Fur Day,[80] allowing for more detailed graphics with multiple, multi-layered textures across all surfaces.

Emulation[edit]

Several Nintendo 64 games have been released for the Wii and Wii U Virtual Console (VC) services and are playable with the Classic Controller, GameCube controller, Wii U Pro Controller, or Wii U GamePad. Differences include a higher resolution and a more consistent framerate than the Nintendo 64 originals. Some features, such as Rumble Pak functionality, are not available in the Wii versions. Some features are also changed on the Virtual Console releases. For example, the VC version of Pokémon Snap allows players to send photos through the Wii's message service, and Wave Race 64's in-game content was altered due to the expiration of the Kawasaki license. Several games developed by Rare were released on Microsoft's Xbox Live Arcade service, including Banjo-Kazooie, Banjo-Tooie, and Perfect Dark, following Microsoft's acquisition of Rareware in 2002. One exception is Donkey Kong 64, released in April 2015 on the Wii U Virtual Console, as Nintendo retained the rights to the game. Several Nintendo 64 games via Nintendo Switch Online + Expansion Pack as the expanded tier of the Nintendo Switch Online were released on October 25, 2021 in North America and October 26, 2021 in Overseas.[120]

Several unofficial third-party emulators can play Nintendo 64 games on other platforms, such as Windows, Macintosh, and smartphones.

Accessories[edit]

Nintendo 64 accessories include the Rumble Pak and the Transfer Pak.

The controller is shaped like an "M", employing a joystick in the center. Popular Electronics called its shape "evocative of some alien space ship". While noting that the three handles could be confusing, the magazine said, "the separate grips allow different hand positions for various game types".[47]

64DD[edit]

Nintendo released a peripheral platform called 64DD, where "DD" stands for "Disk Drive". Connecting to the expansion slot at the bottom of the system, the 64DD turns the Nintendo 64 console into an Internet appliance, a multimedia workstation, and an expanded gaming platform. This large peripheral allows players to play Nintendo 64 disk-based games, capture images from an external video source, and it allowed players to connect to the now-defunct Japanese Randnet online service. Not long after its limited mail-order release, the peripheral was discontinued. Only nine games were released, including the four Mario Artist games (Paint Studio, Talent Studio, Communication Kit, and Polygon Studio). Many planned games were eventually released in cartridge format or on other game consoles. The 64DD and the accompanying Randnet online service were released only in Japan.

To illustrate the fundamental significance of the 64DD to all game development at Nintendo, lead designer Shigesato Itoi said: "I came up with a lot of ideas because of the 64DD. All things start with the 64DD. There are so many ideas I wouldn't have been allowed to come up with if we didn't have the 64DD". Shigeru Miyamoto concluded: "Almost every new project for the N64 is based on the 64DD. ... we'll make the game on a cartridge first, then add the technology we've cultivated to finish it up as a full-out 64DD game".[121]

iQue Player[edit]

The iQue Player was a handheld TV game Nintendo 64 system that released only in China on November 17, 2003, after China banned video game consoles. The games that were released in the iQue Player's lifetime (from 2003 to 2016) are Super Mario 64, The Legend of Zelda: Ocarina of Time, Mario Kart 64, Wave Race 64, Star Fox 64, Yoshi's Story, Paper Mario, Super Smash Bros., F-Zero X, Dr. Mario 64, Excitebike 64, Sin and Punishment, Custom Robo and Animal Crossing.

Reception[edit]

Critical reception[edit]

The Nintendo 64 received acclaim from critics. Reviewers praised the console's advanced 3D graphics and gameplay, while criticizing the lack of games. On G4techTV's Filter, the Nintendo 64 was voted up to No. 1 by registered users.

In February 1996, Next Generation magazine called the Nintendo Ultra 64 the "best kept secret in videogames" and the "world's most powerful game machine". It called the system's November 24, 1995, unveiling at Shoshinkai "the most anticipated videogaming event of the 1990s, possibly of all time".[122] Previewing the Nintendo 64 shortly prior to its launch, Time magazine praised the realistic movement and gameplay provided by the combination of fast graphics processing, pressure-sensitive controller, and the Super Mario 64 game. The review praised the "fastest, smoothest game action yet attainable via joystick at the service of equally virtuoso motion", where "[f]or once, the movement on the screen feels real".[123]: 61 Asked if consumers should buy a Nintendo 64 at launch, buy it later, or buy a competing system, a panel of six GamePro editors voted almost unanimously to buy at launch; one editor said consumers who already own a PlayStation and are on a limited budget should buy it later, and all others should buy it at launch.[124]

At launch, the Los Angeles Times called the system "quite simply, the fastest, most graceful game machine on the market". Its form factor was described as small, light, and "built for heavy play by kids" unlike the "relatively fragile Sega Saturn". Showing concern for a major console product launch during a sharp, several-year long, decline in the game console market, the review said that the long-delayed Nintendo 64 was "worth the wait" in the company's pursuit of quality. Although the Times expressed concerns about having only two launch games at retail and twelve expected by Christmas, this was suggested to be part of Nintendo's "penchant for perfection", as "while other platforms offer quite a bit of junk, Nintendo routinely orders game developers back to the boards to fix less-than-perfect titles". Describing the quality control incentives associated with cartridge-based development, the Times cited Nintendo's position that cartridge game developers tend to "place a premium on substance over flash", and noted that the launch games lack the "poorly acted live-action sequences or half-baked musical overtures" which it says tend to be found on CD-ROM games. Praising Nintendo's controversial choice of the cartridge medium with its "nonexistent" load times and "continuous, fast-paced action CD-ROMs simply cannot deliver", the review concluded that "the cartridge-based Nintendo 64 delivers blistering speed and tack-sharp graphics that are unheard of on personal computers and make competing 32-bit, disc-based consoles from Sega and Sony seem downright sluggish".[95]

Time named it the 1996 Machine of the Year, saying the machine had "done to video-gaming what the 707 did to air travel". The magazine said the console achieved "the most realistic and compelling three-dimensional experience ever presented by a computer". Time credited the Nintendo 64 with revitalizing the video game market, "rescuing this industry from the dustbin of entertainment history". The magazine suggested that the Nintendo 64 would play a major role in introducing children to digital technology in the final years of the 20th century. The article concluded by saying the console had already provided "the first glimpse of a future where immensely powerful computing will be as common and easy to use as our televisions".[125]: 73 The console also won the 1996 Spotlight Award for Best New Technology.[126]

Popular Electronics complimented the system's hardware, calling its specifications "quite impressive". It found the controller "comfortable to hold, and the controls to be accurate and responsive".[47]

In a 1997 year-end review, a team of five Electronic Gaming Monthly editors gave the Nintendo 64 scores of 8.0, 7.0, 7.5, 7.5, and 9.0. They highly praised the power of the hardware and the quality of the first-party games, especially those developed by Rare's and Nintendo's internal studios, but also commented that the third-party output to date had been mediocre and the first-party output was not enough by itself to provide Nintendo 64 owners with a steady stream of good games or a full breadth of genres.[127] Next Generation's end of 1997 review expressed similar concern about third party support, while also noting signs that the third party output was improving, and speculated that the Nintendo 64's arrival late in its generation could lead to an early obsolescence when Sony and Sega's successor consoles launched. However, they said that for some, Nintendo's reliably high-quality software would outweigh those drawbacks, and gave the system 3 1/2 out of 5 stars.[128]

Developer Factor 5, which created some of the system's most technologically advanced games along with the system's audio development tools for Nintendo, said, "[T]he N64 is really sexy because it combines the performance of an SGI machine with a cartridge. We're big arcade fans, and cartridges are still the best for arcade games or perhaps a really fast CD-ROM. But there's no such thing for consoles yet [as of 1998]".[129]

Sales[edit]

The Nintendo 64 was in heavy demand upon its release. David Cole, industry analyst, said "You have people fighting to get it from stores".[63] Time called the purchasing interest "that rare and glorious middle-class Cabbage Patch-doll frenzy". The magazine said celebrities Matthew Perry, Steven Spielberg, and Chicago Bulls players called Nintendo to ask for special treatment to get their hands on the console.[130] The console had only two launch games, with Super Mario 64 as its killer app.

During the system's first three days on the market, retailers sold 350,000 of 500,000 available console units.[63] During its first four months, the console yielded 500,000 unit sales in North America.[131] Nintendo successfully outsold Sony and Sega early in 1997 in the United States;[132] and by the end of its first full year, 3.6 million units were sold in the United States.[133] BusinessWire reported that the Nintendo 64 was responsible for Nintendo's sales having increased by 156% by 1997.[132] Five different Nintendo 64 games exceeded 1 million in sales during 1997.[134]

After a strong launch year, the decision to use the cartridge format is said to have contributed to the diminished release pace and higher price of games compared to the competition, and thus Nintendo was unable to maintain its lead in the United States. The console would continue to outsell the Sega Saturn throughout the generation, but would trail behind the PlayStation.[135]

Nintendo's efforts to attain dominance in the key 1997 holiday shopping season were also hurt by game delays. Five high-profile Nintendo games slated for release by Christmas 1997 (The Legend of Zelda: Ocarina of Time, Banjo-Kazooie, Conker's Quest, Yoshi's Story, and Major League Baseball Featuring Ken Griffey Jr.) were delayed until 1998, and Diddy Kong Racing was announced at the last minute in an effort to somewhat fill the gaps.[136][137][138] In an effort to take the edge off of the console's software pricing disadvantage, Nintendo worked to lower manufacturing costs for Nintendo 64 cartridges, and leading into the 1997 holiday shopping season announced a new pricing structure which amounted to a roughly 15% price cut on both first-party and third-party games. Response from third-party publishers was positive, with key third-party publisher Capcom saying the move led them to reconsider their decision not to publish games for the console.[139][140]

In Japan, the console was not as successful, failing to outsell the PlayStation and the Sega Saturn. Benimaru Itō, a developer for Mother 3 and friend of Shigeru Miyamoto, speculated in 1997 that the Nintendo 64's lower popularity in Japan was due to the lack of role-playing video games.[141] Nintendo CEO Hiroshi Yamauchi also said the console's lower popularity in Japan was most likely due to lack of role-playing games, and the small number of games being released in general.[140]

Nintendo reported that the system's vintage hardware and software sales had ceased by 2004, three years after the GameCube's launch; as of December 31, 2009, the Nintendo 64 had yielded a lifetime total of 5.54 million system units sold in Japan, 20.63 million in the Americas, and 6.75 million in other regions, for a total of 32.93 million units.[7] The Aleck 64 is a Nintendo 64 design in arcade form, designed by Seta in cooperation with Nintendo, and sold from 1998 to 2003 only in Japan.[142]

Legacy[edit]

The Nintendo 64 is one of the most recognized video game systems in history,[143] Designed in tandem with the controller, Super Mario 64 and The Legend of Zelda: Ocarina of Time are widely considered by critics and the public to be two of the greatest and most influential games of all time. GoldenEye 007 is one of the most influential games for the shooter genre.[144]

See also[edit]

Notes[edit]

References[edit]

- ^ "Nintendo 64 Breaks Loose". IGN. September 26, 1996. Archived from the original on October 18, 2015. Retrieved November 12, 2015.

- ^ Kohler, Chris. "Nintendo 64 Came Out 20 Years Ago—Here's How I Felt About It then". Wired.

- ^ a b "Long-awaited Nintendo 64 machine hits stores". The Signal. Santa Clarita. June 24, 1996.

- ^ a b Younge, Gary (March 1, 1997). "Battle of the giants launched". The Guardian. London.

- ^ Curtis, Maree (March 2, 1997). "Remember the games of the old school yard". The Age. Melbourne.

- ^ "Consolidated Sales Transition by Region" (PDF). First console by Nintendo. January 27, 2021. Archived from the original (PDF) on February 24, 2011. Retrieved February 14, 2010.

- ^ a b "Consolidated Sales Transition by Region" (PDF). Nintendo. January 27, 2010. Archived from the original (PDF) on February 24, 2011. Retrieved November 25, 2015.

- ^ "All Time Top 20 Best Selling Games". May 21, 2003. Archived from the original on February 21, 2006. Retrieved March 27, 2008.

- ^ Frank, Allegra (October 20, 2016). "Nintendo Switch Will Use Cartridges". Polygon. Washington DC: Vox Media. Archived from the original on October 20, 2016. Retrieved October 25, 2017.

- ^ a b c d Fisher, Lawrence M (May 6, 1995). "Nintendo Delays Introduction of Ultra 64 Video-Game Player". The New York Times. Archived from the original on November 7, 2014. Retrieved January 23, 2015.

- ^ Hatfield, Daemon. "Nintendo 64 is Number 9". IGN. Archived from the original on November 18, 2015. Retrieved November 11, 2015.

- ^ a b c d e f g "Nintendo and Silicon Graphics join forces to create world's most advanced video entertainment technology" (Press release). Silicon Graphics, Inc. September 4, 1993. Archived from the original on July 7, 1997. Retrieved December 29, 2014.

- ^ a b c d e Brandt, Richard L. (October 1995). "Nintendo Battles for its Life". Upside. Vol. 7, no. 10.

- ^ a b Fisher, Lawrence M. (August 21, 1993). "COMPANY NEWS; Video Game Link Is Seen For Nintendo". International New York Times. Archived from the original on February 8, 2015. Retrieved February 7, 2015.

- ^ a b "Tom Kalinske Interview". Sega-16. Archived from the original on February 7, 2009. Retrieved December 17, 2009.

- ^ a b Cochrane, Nathan (1993). "PROJECT REALITY PREVIEW by Nintendo/Silicon Graphics". GameBytes. No. 21. taken from Vision, the SGI newsletter. Archived from the original on August 18, 2017. Retrieved October 16, 2017.

- ^ Semrad, Ed (October 1993). "Nintendo Postpones Intro of New System... Again!". Electronic Gaming Monthly. No. 51. Ziff Davis. p. 6.

- ^ "SILICON GRAPHICS UNVEILS 'REALITY IMMERSION TECHNOLOGY' FOR NINTENDO 64 AT U.S. DEBUT" (Press release). Silicon Graphics, Inc. May 15, 1996. Archived from the original on October 16, 2017. Retrieved October 16, 2017.

- ^ "Reality Check". GamePro. No. 56. March 1994. p. 184.

- ^ Johnston, Chris; Riccardi, John (1996). Electronic Gaming Monthly's Player's Guide to Nintendo 64 Video Games. Ziff-Davis Publishing. p. 18.

- ^ Higgins, David (April 22, 1997). "Nintendo's black box hides a brilliant brain". The Australian.

The Nintendo 64's simplicity is a key factor for projected sales of 50 million units over a decade-long product life cycle, according to Mr Jim Foran, SGI's director of engineering for the project

- ^ a b c d e Haigh-Hutchinson, Mark (January 1997). "Classic Postmortem: Star Wars: Shadows Of The Empire". Game Developer. Archived from the original on April 2, 2015. Retrieved February 5, 2015.

- ^ a b "Silicon Graphics: showing off". Edge. No. 7. April 1994. pp. 18–19. Retrieved December 14, 2015.

- ^ Gaming Gossip. Electronic Gaming Monthly. Issue 69. Pg.52. April 1995.

- ^ "Nintendo 64". Next Generation. No. 44. August 1998. p. 40. Retrieved December 14, 2015.

- ^ a b c Willcox, James K. (April 1996). "The Game is 64 Bits". Popular Mechanics. p. 134. Archived from the original on October 22, 2020. Retrieved October 16, 2017.

- ^ "ANGEL STUDIOS JOINS NINTENDO ULTRA 64 DREAM TEAM" (Press release). Redmond, WA. February 15, 1995. Archived from the original on October 24, 2017. Retrieved October 16, 2017 – via Business Wire.

World renowned computer graphics studio makes transition from "The Lawnmower Man" and MTV award-winning music videos to develop game for Nintendo's 64-bit home video game system.

- ^ a b "Nintendo Ultra 64". Computer and Video Games. No. 171. UK. February 1996. Archived from the original on August 7, 2022. Retrieved August 7, 2022.

- ^ Conrad, Jeremy (August 3, 2001). "A Brief History of N64". IGN. Archived from the original on October 16, 2017. Retrieved October 16, 2017.

- ^ "Nintendo Power". Nintendo Power. No. 74. July 1995.

Mindscape officially joined the Dream Team at E3 with the announcement of Monster Dunk for the Nintendo Ultra 64."

- ^ McGowan, Chris (September 4, 1993). "Nintendo, Silicon Graphics Team for Reality Check". Billboard. p. 89. Archived from the original on August 13, 2021. Retrieved October 16, 2017.

[It] could be a cartridge system, a CD system, or both, or something not ever used before

- ^ a b Gillen, Marilyn A. (June 25, 1994). "Billboard (June 25, 1994)". Billboard. Archived from the original on August 13, 2021. Retrieved September 2, 2014.

Right now, cartridges offer faster access time and more speed of movement and characters than CDs. So, we'll introduce our new hardware with cartridges. But eventually, these problems with CDs will be overcome. When that happens, you'll see Nintendo using CD as the software storage medium for our 64-bit system. — Howard Lincoln, chairman of Nintendo of America, 1994

- ^ "Nintendo Ultra 64". Archived from the original on February 4, 2009. Retrieved January 14, 2009.

- ^ "Atari Jaguar". Archived from the original on September 18, 2009. Retrieved January 14, 2009.

- ^ "Atari Jaguar". Archived from the original on January 30, 2009. Retrieved January 14, 2009.

- ^ "Midway Takes Project Reality to the Arcades, Williams Buys Tradewest". GamePro. No. 59. June 1994. p. 182.

- ^ a b "Killer Instinct". Archived from the original on February 4, 2009. Retrieved January 14, 2009.

- ^ "MIDWAY KILLER INSTINCT HARDWARE". System 16. Archived from the original on February 4, 2009. Retrieved December 14, 2015.

- ^ "Killer Instinct Hardware". Archived from the original on February 4, 2009. Retrieved January 14, 2009.

- ^ "Nintendo 64 Homes in on Japan". Next Generation. No. 12. Imagine Media. December 1995. p. 19.

- ^ "Gaming Gossip". Electronic Gaming Monthly. No. 74. Ziff Davis. September 1995. p. 44.

- ^ "Say Goodbye to Ultra". Electronic Gaming Monthly. No. 81. Ziff Davis. April 1996. p. 16.

- ^ Lindsay (November 5, 2011). "The 64DREAM – November 1996". Yomuka!. Archived from the original on November 8, 2011. Retrieved November 7, 2011.

- ^ Liedholm, Marcus (January 1, 1998). "The N64's Long Way to completion". Nintendo Land. Archived from the original on March 4, 2008. Retrieved March 27, 2008.

- ^ "Nintendo 64 Hardware Profile". Archived from the original on October 18, 2005. Retrieved January 11, 2009.

- ^ a b "Coverage of the Nintendo Ultra 64 Debut from Game Zero". Game Zero. Archived from the original on October 11, 2007. Retrieved March 27, 2008.

- ^ a b c d e "(Will You Still Love Me) When I'm 64". Popular Electronics. Vol. 14, no. 3. March 1997.

- ^ Semrad, Ed (April 1996). "N64 Delayed... Again?". Electronic Gaming Monthly. No. 81. Ziff Davis. p. 6.

- ^ "Ultra 64 "Delayed" Until April 1996?". Electronic Gaming Monthly. No. 72. Ziff Davis. July 1995. p. 26.

- ^ "Kyoto Microcomputer Co., Ltd" (PDF). Kyoto Microcomputer Co., Ltd. Archived (PDF) from the original on January 14, 2015. Retrieved January 14, 2015.

- ^ "Metrowerks Announces Partnership with Kyoto Microcomputer Co. Ltd" (Press release). November 4, 1998. Archived from the original on January 15, 2015. Retrieved January 14, 2015.

[Kyoto Microcomputer Co. Ltd.] is the authorized tools vendor for Nintendo 64.

- ^ "So Howard, What's the Excuse this Time?". Next Generation. No. 17. Imagine Media. May 1996. pp. 6–8.

- ^ "The Ad Blitz Kicks Off". Electronic Gaming Monthly. No. 81. Ziff Davis. April 1996. p. 17.

- ^ "Ultra Hype for the Ultra 64". GamePro. No. 89. IDG. February 1996. p. 12.

- ^ "Big in Japan: Nintendo 64 Launches at Last". Next Generation. No. 21. Imagine Media. September 1996. pp. 14–16.

- ^ "N64's Japanese Debut". GamePro. No. 96. IDG. September 1996. p. 32.

- ^ Semrad, Ed (September 1996). "Electronic Gaming Monthly". Electronic Gaming Monthly. No. 86. Ziff Davis. p. 6.

- ^ McCall, Scott (September 28, 1996). "N64's U.S. Launch". Teleparc. Archived from the original on October 12, 2015. Retrieved September 29, 2015.

- ^ Svenson, Christian (December 1996). "Nintendo 64 Frenzy". Next Generation. No. 24. Imagine Media. p. 28.

Nintendo had rather hopefully put a September 29 deadline on the on-sale date. But virtually every retailer in the country was shifting boxes by the 26th. Nintendo, realizing it could not hope to stop the malaise, yielded.

- ^ "Launch Surprises: Nintendo Cuts Price of N64, Drops Cruis'n USA as Launch Title". GamePro. No. 98. IDG. November 1996. p. 26.

- ^ "Il y a 20 ans, la PlayStation sortait en France". www.gamekult.com (in French). September 29, 2015. Archived from the original on May 1, 2021. Retrieved March 5, 2021.

- ^ "Ultra 64 Delayed until September 30". Next Generation. No. 16. Imagine Media. April 1996. pp. 14–15.

- ^ a b c Stone, BradCroal, N'Gai. "Nintendo's Hot Box." Newsweek 128.16 (1996): 12. Military & Government Collection. Web. July 24, 2013.

- ^ Hill, Charles (February 21, 2012). Strategic Management Cases: An Integrated Approach, 10th ed. Cengage Learning. ISBN 978-1285402154. Archived from the original on August 26, 2016. Retrieved December 13, 2013.

- ^ Miller, Cyndee. "Sega Vs. Nintendo: This Fights almost as Rough as their Video Games." Marketing News 28.18 (1994): 1-. ABI/INFORM Global; ProQuest Research Library. Web. May 24, 2012.

- ^ Editors, Business. "New Nintendo 64 Pricing Set at $129.95, $10 Software Coupons to Continue Sales Momentum." Business Wire: 1. August 25, 1998. ProQuest. Web. July 23, 2013.

- ^ a b c "10 Reasons Why Nintendo 64 Will Kick Sony's and Sega's Ass (& 20 Reasons Why it Won't)". Next Generation. No. 20. Imagine Media. August 1996. pp. 36–43.

- ^ "Nintendo 64 Marketing Specs". Next Generation. No. 20. Imagine Media. August 1996. p. 38.

- ^ "Promotions: Mills Gets Foot Up with Nintendo Link-up." BRANDWEEK formerly Adweek Marketing Week. (January 18, 1999 ): 277 words. LexisNexis Academic. Web. Date. Retrieved 2013/07/24.

- ^ Wasserman, Todd. "Nintendo: Pokemon, Peripherals Get $30M." Brandweek 41.7 (2000): 48. Business Source Complete. Web. July 24, 2013.

- ^ a b "Main specifications of VR4300TM-series". NEC. Archived from the original on July 10, 2020. Retrieved May 20, 2006.

- ^ "Nintendo 64 Architecture: A Practical Analysis". Rodrigo Copetti. September 12, 2019. Archived from the original on July 30, 2023. Retrieved August 4, 2023.

- ^ "Total Recall: The Future of Data Storage". Next Generation. No. 23. Imagine Media. November 1996. p. 43.

The current trend now, with both the M2 and N64, is back towards a unified memory system.

- ^ a b "Which Game System is the Best!?". Next Generation. No. 12. Imagine Media. December 1995. pp. 83–85.

- ^ "Nintendo Support: Nintendo 64 AV to TV Hookup". Nintendo. Archived from the original on May 20, 2010. Retrieved February 28, 2010.

- ^ Loguidice, Bill; Barton, Matt (February 24, 2014). Vintage Game Consoles: An Inside Look at Apple, Atari, Commodore, Nintendo, and the Greatest Gaming Platforms of All Time. CRC Press. p. 262. ISBN 9781135006518. Archived from the original on August 13, 2021. Retrieved October 27, 2020.

- ^ a b IGN Staff (December 15, 1998). "Nintendo 64 Expansion Pak". IGN. Archived from the original on September 24, 2015. Retrieved August 7, 2015.

- ^ "Shigeru Miyamoto: The Master of the Game". Next Generation. No. 14. Imagine Media. February 1996. pp. 45–47.

- ^ a b c d e f Maher, Jimmy (December 8, 2023). "Putting the "J" in the RPG, Part 2: PlayStation for the Win The Digital Antiquarian". The Digital Antiquarian. Retrieved December 8, 2023.

- ^ a b "The N64 Hardware". Archived from the original on April 30, 2009. Retrieved January 15, 2009.

- ^ a b "The N64 Hardware". Archived from the original on April 30, 2009. Retrieved January 16, 2009.

- ^ a b "CD Capacity". Archived from the original on March 4, 2016. Retrieved January 16, 2009.

- ^ a b c d "Nintendo 64". Archived from the original on January 29, 2009. Retrieved January 11, 2009.

- ^ a b "Bringing Indy to N64". IGN. November 9, 2000. Archived from the original on September 27, 2013. Retrieved September 24, 2013.

- ^ "Indiana Jones and the Infernal Machine". IGN. December 12, 2000. Archived from the original on September 27, 2013. Retrieved September 24, 2013.

- ^ "Interview: Battling the N64". IGN. November 10, 2000. Archived from the original on September 13, 2007. Retrieved November 13, 2021.

- ^ a b Nintendo Power August 1994 – Pak Watch. Nintendo. 1994. p. 108.

- ^ "Nintendo Ultra 64: The Launch of the Decade?". Maximum: The Video Game Magazine. No. 2. Emap International Limited. November 1995. pp. 107–8.

- ^ Noble, McKinley. "5 Biggest Game Console Battles". PC World. Archived from the original on February 10, 2020. Retrieved November 19, 2019.

- ^ Sun, Leo (February 12, 2014). "3 Ways Nintendo's Fear of Piracy Shaped its Business". The Motley Fool. Archived from the original on September 4, 2019. Retrieved November 19, 2019.

- ^ Ryan, Michael E. "'I Gotta Have This Game Machine!' (Cover Story)." Familypc 7.11 (2000): 112. MasterFILE Premier. Web. July 24, 2013.

- ^ "1996: The Year of the Videogame". Next Generation. No. 13. Imagine Media. January 1996. p. 71.

- ^ a b "Ultra 64: Nintendo's Shot at the Title". Next Generation. No. 14. Imagine Media. February 1996. pp. 36–44.

- ^ a b c Curtiss, Aaron (September 30, 1996). "New Nintendo 64 is a Technical Wonder; Leisure: The Cartridge-Based Game Machine Boasts Blistering Speed and Super-Sharp Graphics". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on January 24, 2015. Retrieved January 21, 2015.

- ^ "What's Wrong with N64 Software?". Next Generation. No. 29. Imagine Media. May 1997. p. 43.

- ^ a b c "Nintendo 64". Archived from the original on November 26, 2013. Retrieved January 15, 2009.

- ^ "Elusions: Final Fantasy 64". Archived from the original on January 14, 2012. Retrieved January 11, 2009.

- ^ "Squaresoft Head for Sony". Maximum: The Video Game Magazine. No. 4. Emap International Limited. March 1996. p. 105.

- ^ a b "Most Popular Nintendo 64 Games". Archived from the original on December 18, 2008. Retrieved January 11, 2009.

- ^ "Nintendo 64 ROMS". Retrieved January 14, 2009.

- ^ "Nintendo 64". GameConsoles.co.uk. Archived from the original on November 6, 2007. Retrieved January 14, 2009.

- ^ "Zelda Ocarina of Time Cartridge Trivia". Archived from the original on March 3, 2016. Retrieved January 14, 2009.

- ^ "Nintendo Wakes Up." The Economist August 3, 1996: 55-. ABI/INFORM Global; ProQuest Research Library. Web. May 24, 2012.

- ^ Croal, N'Gai (September 4, 2000). "It's Hip To Be Square". Newsweek. Vol. 136, no. 10. Masato Kawaguchi and Marc Saltzman in Japan. pp. 53–54. Archived from the original on October 25, 2020. Retrieved August 3, 2020.

- ^ "N64 Top 10 List". Electronic Gaming Monthly. No. 85. Ziff Davis. August 1996. p. 17.

- ^ "Launch Puts N64 on Map". Electronic Gaming Monthly. No. 89. Ziff Davis. December 1996. pp. 20–21.

- ^ "IGN N64: Editors' Choice Games". IGN. Archived from the original on May 9, 2008. Retrieved March 27, 2008.

- ^ "Nintendo Boosts N64 Production". Electronic Gaming Monthly. No. 93. Ziff Davis. April 1997. p. 22.

- ^ "Super Mario Sales Data: Historical Units Sold Numbers for Mario Bros on NES, SNES, N64..." Archived from the original on October 1, 2017. Retrieved November 12, 2015.

- ^ "Gran Turismo Series Shipments Hit 50 Million". PCWorld. May 9, 2008. Archived from the original on May 5, 2019. Retrieved November 12, 2015.

- ^ "Masterpiece: Final Fantasy VII". Ars Technica. May 7, 2010. Archived from the original on May 4, 2012. Retrieved November 12, 2015.

- ^ "GT Countdown Top 10 First-Person Shooters of All Time". GameTrailers. December 4, 2012. Archived from the original on February 12, 2016. Retrieved February 5, 2016.

- ^ a b "Legend of Zelda: Ocarina of Time". Metacritic. Archived from the original on November 21, 2010. Retrieved February 3, 2010. Metacritic here states that Ocarina of Time is "[c]onsidered by many to be the greatest single-player video game ever created in any genre..."

- ^ "Ocarina of Time Hits Virtual Console". 1UP.com. Archived from the original on June 29, 2011. Retrieved February 2, 2010.

- ^ "The Best Video Games in the History of Humanity". Filibustercartoons.com. Archived from the original on September 21, 2010. Retrieved September 12, 2010.

- ^ "Nintendo DS vs. Nintendo 64". Archived from the original on December 28, 2008. Retrieved January 15, 2009.

- ^ "Saturn Game Tutorial". Archived from the original on February 4, 2009. Retrieved January 15, 2009.

- ^ "Nintendo 64". Archived from the original on February 4, 2009. Retrieved January 15, 2009.

- ^ Peters, Jay (September 23, 2021). "Nintendo Switch Online is getting an 'expansion pack' with N64 and Genesis games". The Verge. Archived from the original on September 24, 2021. Retrieved September 23, 2021.

- ^ Miyamoto, Shigeru; Itoi, Shigesato (December 1997). "A friendly discussion between the "Big 2"". The 64DREAM. p. 91. Archived from the original on March 10, 2018. Retrieved January 14, 2015.

- ^ "Ultra 64: Nintendo's shot at the title". Next Generation. No. 14. February 1996. Retrieved February 5, 2015.

- ^ Krantz, Michael; Jackson, David S. (May 20, 1996). "Super Mario's Dazzling Comeback". Time International. Vol. 147, no. 21 (South Pacific ed.). Time, Inc. Archived from the original on January 28, 2015. Retrieved January 23, 2015.

- ^ "To Buy or Not to Buy". GamePro. No. 97. IDG. October 1996. p. 36.

- ^ Krantz, Michael (November 25, 1996). "64 Bits of Magic". Time Magazine. Vol. 148, no. 24. Archived from the original on January 28, 2015. Retrieved January 24, 2015.

- ^ "Spotlight Award Winners". Next Generation. No. 31. Imagine Media. July 1997. p. 21.

- ^ "EGM's Special Report: Which System Is Best?". 1998 Video Game Buyer's Guide. Ziff Davis. March 1998. pp. 42–45.

- ^ "Where to Play? The Dust Settles". Next Generation. No. 36. Imagine Media. December 1997. pp. 55–58.

- ^ Eggebrecht, Julian (February 23, 1998). "Factor 5 Interview (Part I)" (Interview). Interviewed by Peer Schneider. Archived from the original on January 13, 2015. Retrieved January 13, 2015.

- ^ Krantz, Michael. "Mario Plays Hard To Get." Time 148.26 (1996): 60. Military & Government Collection. Web. July 24, 2013.

- ^ "Sega Dreamcast Sales Outstrip Expectations in N. America". Comline Computers. October 6, 1999. Archived from the original on July 14, 2012. Retrieved March 27, 2008.

- ^ a b "1997: So far, the year of Nintendo; company sales up 156 percent; driven by Nintendo 64 success". Atlanta: Business Wire. June 18, 1997. Archived from the original on November 26, 2015. Retrieved November 12, 2015.

- ^ "Nintendo Delivers Early Holiday Cheer With New Software Prices. – Free Online Library". Thefreelibrary.com. Archived from the original on February 24, 2014. Retrieved March 2, 2014.

- ^ "View to a Million". Electronic Gaming Monthly. No. 104. Ziff Davis. March 1998. p. 32.

- ^ Kent, Steven L. (2002). The Ultimate History of Video Games: The Story Behind the Craze that Touched our Lives and Changed the World. New York: Random House International. ISBN 978-0-7615-3643-7. OCLC 59416169. Archived from the original on July 28, 2014. Retrieved October 14, 2015.

- ^ "Nintendo's Holiday Surprise!: Diddy Kong Racing Announced; Griffey and Banjo-Kazooie Delayed". GamePro. No. 110. IDG. November 1997. p. 30.

- ^ "Nintendo Dealt Blow". Next Generation. No. 35. Imagine Media. November 1997. p. 22.

- ^ "N64 Games Delayed Again". Electronic Gaming Monthly. No. 100. Ziff Davis. November 1997. p. 24.

- ^ "Nintendo Gets Reasonable". Next Generation. No. 36. Imagine Media. December 1997. p. 20.

- ^ a b "Nintendo's Space World 1997". Next Generation. No. 38. Imagine Media. February 1998. pp. 22–23.

- ^ Takao Imamura; Shigeru Miyamoto (August 1997). "Pak Watch E3 Report "The Game Masters"". Nintendo Power. Nintendo. pp. 104–105.

- ^ "Seta Aleck64 Hardware". System 16. Archived from the original on February 3, 2016. Retrieved November 25, 2015.

- ^ "Nintendo 64 Week: Day Two". IGN. October 2008. Archived from the original on July 26, 2011. Retrieved November 13, 2021.

- ^ "Filter Face Off: Top 10 Best Game Consoles". g4tv.com. Archived from the original on July 2, 2017. Retrieved May 3, 2013.

External links[edit]

- Billboard Magazine of May 18, 1996, p.58, covering the launch of Nintendo 64, including Yamauchi's explanation of cartridge strategy and negotiations about Netscape's online strategy for Nintendo 64

- "Why Netscape Almost Didn't Exist", on Andreesson's choice to cofound Netscape instead of working on N64, and later proposing N64's first online strategy

- "Nintendo 64". Archived from the original on October 17, 2007.

- Index of all Nintendo 64 promotional videos

- US Patent for the N64

- The Most Complete N64 Game Releaselist by NESWORLD