Somers Town, London

This article needs additional citations for verification. (March 2008) |

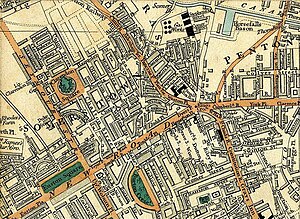

Somers Town is an inner-city district in North West London. It has been strongly influenced by the three mainline north London railway termini: Euston (1838), St Pancras (1868) and King's Cross (1852), together with the Midland Railway Somers Town Goods Depot (1887) next to St Pancras, where the British Library now stands. It was named after Charles Cocks, 1st Baron Somers (1725–1806).[1][2] The area was originally granted by William III to John Somers (1651–1716), Lord Chancellor and Baron Somers of Evesham.[3]

Historically, the name "Somers Town" was used for the larger triangular area between the Pancras, Hampstead, and Euston Roads,[1] but it is now taken to mean the rough rectangle centred on Chalton Street and bounded by Pancras Road, Euston Road, Eversholt Street, Crowndale Road, and the railway approaches to St Pancras station. Somers Town was originally within the medieval Parish of St Pancras, Middlesex, which in 1900 became the Metropolitan Borough of St Pancras. In 1965 the Borough of St Pancras was abolished and its area became part of the London Borough of Camden.[4][5]

History

[edit]

600-1839

[edit]

St Pancras Old Church is believed by many to be one of the oldest Christian sites in England. The churchyard remains consecrated but is managed by Camden Council as a park. It holds many literary associations, from Charles Dickens to Thomas Hardy, as well as memorials to dignitaries, including the remarkable tomb of architect Sir John Soane.

In the mid 1750s the New Road was established to bypass the congestion of London; Somers Town lay immediately north of this east–west toll road. In 1784, the first housing was built at the Polygon amid fields, brick works and market gardens on the northern fringes of London. Mary Wollstonecraft, writer, philosopher and feminist, lived there with her husband William Godwin, and died there in 1797 after giving birth to the future Mary Shelley, author of Frankenstein. The area appears to have appealed to middle-class people fleeing the French Revolution. The site of the Polygon is now occupied by a block of council flats called Oakshott Court, which features a commemorative plaque for Wollstonecraft.

St Mary's Church opened near the Polygon in 1827 and is now the parish church.[6] In 1830 the first on-duty fatality for the newly founded Metropolitan Police occurred when PC Joseph Grantham was kicked to death while trying to break up a street fight in Smiths Place, Somers Town.[7] The Polygon deteriorated socially as the surrounding land was subsequently sold off in smaller lots for cheaper housing, especially after the start of construction in the 1830s of the railway lines into Euston, St Pancras and King's Cross. In this period the area housed a large transient population of labourers and the population density of the area soared.

1840-1899

[edit]When St Luke's Church, near King's Cross, was demolished to make way for the construction of the Midland Railway's St Pancras station and its Midland Grand Hotel, the estimated 12,000 inhabitants of Somers Town at that time were deprived of that place of worship, as the church building was re-erected in Kentish Town, though St Mary's remained and St Matthew's Oakley Square was added in 1856.[8] In 1868 the lace merchant and philanthropist George Moore funded a new church, known as Christ Church and an associated school in Chalton Street with an entrance in Ossulston Street. The school accommodated about 600 children. Christ Church and the adjacent school were destroyed in a World War II bombing raid and no trace remains today, the site being occupied by a children's play area and sports court, with its parish transferred to Old Saint Pancras Church. By the late 19th century most of the houses in the Polygon were in multiple occupation, and overcrowding was severe with whole families sometimes living in one room, as confirmed by the social surveys of Charles Booth and Irene Barclay.

Charles Dickens lived in the Polygon briefly as a child and knew the area well. The Polygon, where he once lived, appears in Chapter 52 of The Pickwick Papers (1836), when Mr Pickwick's solicitor's clerk, arriving at Gray's Inn just before ten o'clock, says he heard the clocks strike half past nine as he walked through Somers Town: "It went the half hour as I came through The Polygon." The building makes its appearance again in Bleak House (1852), when it served as the home of Harold Skimpole.[9] In David Copperfield (1850), Johnson (now Cranleigh) Street was the thoroughfare near the Royal Veterinary College, Camden Town, where the Micawbers lived, when Traddles, David Copperfield's friend and schoolfellow, was their lodger.[10]

In A Tale of Two Cities (1859) Roger Cly, the Old Bailey informant, was buried in Old St Pancras Churchyard. The funeral over, later that night Jerry Cruncher and his companions went "fishing" (body snatching), trying unsuccessfully to 'resurrect' Cly.[11] Robert Blincoe (1792–1860), on whose life story Oliver Twist (1838) may be based, was a child inmate at the St Pancras Workhouse. A central character in Dickens’ Our Mutual Friend (1865) is Nicodemus Boffin, nicknamed 'The Golden Dustman' because of the wealth he inherited from his old employer John Harmon, who had made his fortune as a dust contractor at Somers Town.[12]

An infirmary was added to the St Pancras Workhouse, adjacent to St Pancras Old Church in 1848, later becoming the St Pancras Hospital, the only hospital in the area not to have closed since 1980. Its current site includes buildings previously used by the Workhouse. St Mary's Dispensary (later the Elizabeth Garrett Anderson Hospital) opened at 144 Euston Road in 1866, followed by the National Temperance Hospital at 110-112 Hampstead Road in 1873.

1900-1979

[edit]Improvement of the slum housing conditions, amongst the worst in the capital, was first undertaken by St Pancras Borough Council in 1906 at Goldington Buildings, at the junction of Pancras Road and Royal College Street, and continued on a larger scale by the St Pancras House Improvement Society (subsequently the St Pancras & Humanist Housing Association, the present owner of Goldington Buildings) which was established in 1924. Its founders were Church of England priest Father Basil Jellicoe and Irene Barclay, the first woman in Britain to qualify as a chartered surveyor. The Society's Sidney Street and Drummond Street estates incorporated sculpture panels of Doultonware designed by Gilbert Bayes and ornamental finials for the washing line posts designed by the same artist: these are now mostly destroyed or replaced with replicas.[13]

The Hospital for Tropical Diseases moved onto the St Pancras Hospital site in 1948. Further social housing was built by the London County Council, which began construction of the Ossulston Estate in 1927. There remains a small number of older Grade 2 listed properties, mostly Georgian terraced houses. During the early 1970s the neighborhood comprising Greater London Council-owned housing in Charrington, Penryn, Platt and Medburn Streets was a centre for the squatting movement.[14]

1979-present

[edit]In the 1980s, some council tenants took advantage of the 'right to buy' scheme and bought their homes at a substantial discount. Later they moved away from the area. The consequence was an influx of young semi-professional people, resulting in a changing population. Somers Town experienced ethnic tension between whites and Bengalis in the early 1990s, climaxing in the murder of Richard Everitt in 1994.[15][16] Major construction work along the eastern side of Somers Town was completed in 2008, to allow for the Eurostar trains to arrive at the refurbished St Pancras station. This involved the excavation of part of the St Pancras Old Churchyard, the human remains being re-interred at St Pancras and Islington Cemetery in East Finchley.[17]

Land at Brill Place, previously earmarked for later phases of the British Library development, became available when the library expansion was cancelled and was used as site offices for the High Speed 1 terminal development and partly to allow for excavation of a tunnel for the new Thameslink station. It was then acquired as the site for the Francis Crick Institute (formerly the UK Centre for Medical Research and Innovation), a major medical research institute established by a partnership of Cancer Research UK, Imperial College London, King's College London, the Medical Research Council, University College London (UCL) and the Wellcome Trust.[18][19]

References in film and music

[edit]A number of significant films have been set in Somers Town: the 1955 Ealing comedy The Ladykillers with Alec Guinness and Peter Sellers; Neil Jordan's Mona Lisa of 1986, featuring Bob Hoskins; Mike Leigh's 1988 film High Hopes; Anthony Minghella's 2006 romantic drama Breaking and Entering starring Jude Law and Juliette Binoche; and in 2008 Shane Meadows's Somers Town, which was filmed almost entirely in and around Phoenix Court, a low-rise council property in Purchese Street.[20] The area is mentioned in the Pogues song 'Transmetropolitan', the first song written by the band, who used to live nearby in St Pancras.[21]

Arts and culture

[edit]Somers Town has a flourishing street market, held in Chalton Street, Wednesday to Friday.[22] The START (Somers Town Art) Festival of Cultures is held on the second Saturday in July, on the site of the market. It is the biggest street festival in the Camden borough and attracts about 10,000 people, bringing together the area's diverse cultural communities.[23]

Infrastructure

[edit]Hospitals

[edit]All the area's hospitals have closed since 1980, apart from St Pancras Hospital, whose large red brick building fronting the complex to the north of St Pancras Gardens is still residential, chiefly as a rehabilitation hospital for the elderly. Other buildings house the headquarters of Camden NHS Primary Care Trust. It also accommodates parts of Islington Primary Care Trust, the Huntley Centre (a mental health unit) and St Pancras Coroner's Court.

Education

[edit]There are two secondary schools in the area, the Roman Catholic co-educational Maria Fidelis Convent School FCJ in Phoenix Road, and the state Regent High School in Charrington Street. Regent High School was established in 1877 and has gone through several name changes, more recently as Sir William Collins Secondary School, then as South Camden Community School. Somers Town Community Sports Centre was built on part of the school playground. The building is leased to a charitable trust that is jointly managed by the school and UCL (UCL is based a few hundred metres to the south of Euston Road and is a major employer of local residents). It is used for 17% of available hours by UCLU's sports teams for training and home matches and for recreational sport by UCL students. As part of Building Schools for the Future plans to expand the school, it is probable that the sports centre will be reintegrated back into the school campus.

There are also three primary schools: Edith Neville (state), St Aloysius (state-aided Catholic) and St Mary and St Pancras (state-aided Church of England). The latter has been built beneath Somerset Court, four floors of university student accommodation units. The children's charity Scene & Heard is also based in Somers Town. It offers a unique mentoring project that partners the inner-city children of Somers Town with volunteer theatre professionals, providing each child who participates with quality one-on-one adult attention and an experience of personal success through the process of writing and performing plays.

Transport

[edit]The nearest London Underground stations are Mornington Crescent, Euston and King's Cross St Pancras. National Rail services operate from the nearby London King's Cross, London St Pancras and London Euston stations. St Pancras International is the terminus for Eurostar services and was the London terminus for the Javelin fast train service to London Olympic Park.[24]

Nearby areas

[edit]- Camden Town to the north

- Euston to the west

- King's Cross to the east

- St Pancras to the south-east

- Bloomsbury to the south

Housing estates

[edit]Modern housing estates in Somers Town include:

- Oakshott Court

- Cooper's Lane Estate

- Ossulston Estate

- Godwin Court

- Crowndale Estate

- Sidney Estate

- Ampthill Square Estate

- Aldenham House

- Wolcott House

- Churchway Estate

- Mayford Estate

- Clyde Court

- Goldington Street Estate

- Bridgeway Street

Notable residents

[edit]- Sir James Bacon (1798–1895), judge and privy councilor, born at 10 The Polygon

- Andrés Bello, (1781–1865), Venezuelan poet, lawmaker, philosopher, and educator lived at 39 Clarendon Square, later at 9 Egremont Place[25]

- Natalie Bennett, former Green Party of England and Wales leader[26]

- Maria Caterina Brignole (1737–1813), Dowager Princess of Monaco, Princess of Condé, fled the French Revolution, buried in St Aloysius[27][28]

- Nell Campbell, actress and singer, lived at 50 Charrington Street while appearing in The Rocky Horror Show

- Guy-Toussaint-Julien Carron (1760–1821), French priest who fled the French Revolution and established the chapel of St Aloysius and other institutions in the area, lived at 1 The Polygon[27]

- Joe Cole, England, Chelsea, Liverpool and West Ham United football player

- Louis Joseph de Bourbon (1736–1818), Prince of Condé, counter-revolutionary leader who fled France[27]

- Jean François de La Marche, Bishop of St. Pol de Léon (1729–1806), priest who fled the French Revolution, buried in St Pancras churchyard[27]

- Catherine Despard (d.1815), political activist and wife of executed seditionist Colonel Edward Despard

- Samuel De Wilde (1751–1832), portrait painter and etcher, lived in Clarendon Square[1]

- Charles Dickens (1812–1870), lived at 29 Johnson (now Cranleigh) Street for four years,[29] then moved in November 1828 to 17 The Polygon

- Arthur Richard Dillon (1721–1806), Archbishop of Narbonne, who fled the French Revolution, buried in St Pancras churchyard[27]

- Francis Aidan Gasquet (1846–1929), Cardinal, Librarian of the Vatican, scholar, was born at 26 Euston Place

- Mary Wollstonecraft Godwin (Mary Shelley) (1797–1851), most famous for her novel Frankenstein, was born at 29 The Polygon

- William Godwin (1756–1836), Enlightenment philosopher, lived at 25 Chalton Street (from 1793), at 17 Evesham Buildings (in Chalton St, from 1797) and at 29 The Polygon (1797-1807)[30]

- John Gale Jones (1769–1838), English radical orator, lived at 10 Brill Terrace (now Coopers Lane) and 32 Middlesex Street[31][32]

- Tom Keell and Alfred Marsh published the anarchist newspaper Freedom from 127 Ossulston Street (1894-1927)[33]

- George Lance (1802–1864), painter, lived in Phoenix St[27]

- Ethel Le Neve (1883–1967), the mistress of Dr Crippen, lived at 17 Goldington Buildings[34]

- Dan Leno (1860–1904), leading music hall comedian and musical theatre actor during the late Victorian era, born at 6 Eve Place[35]

- Doris Lessing (1919–2013), novelist, winner of the 2007 Nobel prize for literature, lived at 60 Charringon Street (street renumbered in late 1970s). In Walking in the Shade she writes of buying her first house in Somers Town[36][37]

- Samuel Mitan (1786–1843), engraver, lived and died at 8 The Polygon [38]

- William Nutter (1759–1802), engraver and draughtsman [39]

- Sidney Richard Percy (1821–1886), one of the most prolific and popular landscape painters of the Victorian era, lived at 11 Johnson (now Cranleigh) Street in 1842

- Antonio Puigblanch (1773–1840), author of The Inquisition Unmasked, London, 1816, lived and died at 51 Johnson (now Cranleigh) Street[40]

- Mary Ann Sainsbury (1849–1927), businesswoman, wife of Sainsbury's supermarket chain founder John James Sainsbury. Born at 4 Little Charles Street (now St Joans House, Phoenix St); her family's shop was at 87 Chalton Street from 1863. In 1882 it became part of the Sainsbury chain.[41]

- Edward Scriven (1775–1841), pre-eminent engraver of his generation, lived and died at 46 Clarendon Square[1][42]

- Benjamin Smith (1754–1833), engraver, lived and worked first at 21 Judd Place‚ then at 65 Ossulston Street[43]

- Fred Titmus (1932–2011), cricketer, lived at 13 Bridgeway Street

- James Tibbits Willmore (1800–1863), engraver, lived at 23 The Polygon[44]

- Harriette Wilson (1786–1845), prominent Regency era courtesan, lived in Duke's Row (now Duke's Road)[45]

- John Wolcot (1738–1819), as "Peter Pindar", the most prolific and successful burlesque poet of the late 18th century, lived and died in Latham Place (now part of Churchway) [46]

- Mary Wollstonecraft (1759–1797), writer and philosopher, died at 29 The Polygon

- William Wordsworth (1770–1850), major Romantic poet, Poet Laureate, lived at 15 Chalton Street in 1795[47]

Street name etymologies

[edit]This is a list of the etymology of Somers Town streets.

- Aldenham Road – Richard Platt, 16th century brewer and local landowner, who gave part of the land for the endowment of Aldenham School, Hertfordshire[48]: 65 [49]: 19–20

- Bridgeway Street – by connection with the Barons Ossulston peerage; formerly Bridgewater Street[50][49]: 244

- Charrington Street – as this land was formerly owned by the Worshipful Company of Brewers, and named for the Charrington Brewery[48]: 65 [49]: 81

- Chenies Place – after local landowners the dukes of Bedford, also titled Barons Russell, of Chenies[49]: 83

- Churchway – as this formed part of old pathway to St Pancras Old Church[49]: 86

- Clarendon Grove – by connection with the Barons Ossulston peerage[49]: 244

- Cranleigh Street – by connection with the Barons Ossulston peerage; formerly Johnson Street[50][49]: 244

- Crowndale Road – as this land was formerly owned by Dukes of Bedford, who also owned land in Crowndale, Devon[48]: 87 [49]: 42

- Doric Way – after the doric Euston Arch, built in 1837, demolished in 1961[48]: 99

- Drummond Crescent – part of the Duke of Grafton's FitzRoy Estate, named after Lady Caroline Drummond, great granddaughter of Charles FitzRoy, 2nd Duke of Grafton[51][49]: 133

- Euston Road – developed in 1756 by the 2nd Duke of Grafton on land belonging to the FitzRoy Estate, named after Euston Hall, the Graftons' family home[51][48]: 113 [49]: 126

- Eversholt Street – after the Dukes of Bedford, whose seat was at Woburn Abbey near Eversholt, Bedfordshire[48]: 113

- Goldington Crescent and Goldington Street – formerly part of the Duke of Bedford's Figs Mead Estate (later Bedford New Town), who also owned land in Goldington, Bedfordshire[5][48]: 87 [49]: 145

- Grafton Place – originally part of the Duke of Grafton's FitzRoy Estate[48]: 139 [49]: 147

- Medburn Street – Richard Platt, 16th century brewer and local landowner, who gave part of his land at Medburn Farm, Hertfordshire for the endowment of Aldenham School[48]: 210 [49]: 20

- Midland Road – after the adjacent railway line, built by the Midland Railway Company; part was formerly Skinner Street, on the Skinners' Company's Estate[48]: 212 [49]: 219–220

- Oakley Square – as this land was formerly owned by Dukes of Bedford, who also owned land in Oakley, Bedfordshire[48]: 231 [49]: 237

- Ossulston Street – named in 1807 in memory of the Saxon-era hundred of Ossulston, thought to be named after a stone boundary marker at Tyburn (now Marble Arch) erected by one Oswulf/Oswald[48]: 237 [49]: 243–244

- Pancras Road – after the adjacent St Pancras Old Church, named for the Roman-era Christian martyr Pancras of Rome[48]: 239 [49]: 246

- Phoenix Road – thought to be after a former tavern of this name; formerly Phoenix Street[50][49]: 255

- Platt Street – after Richard Platt, 16th century brewer, who donated this land to the Worshipful Company of Brewers, who built this street in 1848-53[48]: 248–249 [49]: 258

- Polygon Road – after the Polygon, a 17th-century housing development here instigated by Jacob Leroux and Job Hoare[48]: 251 [50][49]: 259

- Purchese Street – after Frederick Purchese, local resident, vestryman, county council member and Mayor of St Pancras[48]: 257 [49]: 266

- Werrington Street – after Werrington, Cornwall, where local landowners the dukes of Bedford held land;[48]: 337 formerly Clarendon Street[50]

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d Walford, Edward (1878). "Somers Town and Euston Square". Old and New London: A Narrative of Its History, Its People, and Its Places. Illustrated with Numerous Engravings from the Most Authentic Sources. Vol. 5. London: Cassell Petter & Galpin. pp. 340–355. Archived from the original on 26 October 2012. Retrieved 26 June 2011.

- ^ Malcolm, J.P. (1813). "Origin and gradual increase of Somers Town". The Gentleman's Magazine. 83 (November, 1813): 427–429.

- ^ Somers Cocks, J.V. (1967). A History of the Cocks Family (PDF). Ashhurst, New Zealand: J. Somers Cocks. ISBN 0-473-06085-X. Archived (PDF) from the original on 24 July 2011. Retrieved 27 June 2011.

- ^ Palmer, Samuel (1870). St. Pancras; being antiquarian, topographical, and biographical memoranda, relating to the extensive metropolitan parish of St. Pancras, Middlesex; with some account of the parish from its foundation. London: Field & Tuer. Retrieved 21 March 2019.

- ^ a b Cherry, Bridget; Pevsner, Nikolaus (2002). London 4: North. New Haven CT: Yale University Press. ISBN 9780300096538. Archived from the original on 7 April 2023. Retrieved 21 March 2019.

- ^ Miller, Frederick (1874). Saint Pancras, Past and Present: Being Historical, Traditional and General Notes of the Parish. London: Abel Heywood & Son. p. 331. Retrieved 26 May 2013.

- ^ Aston, Mark (2005). Foul Deeds & Suspicious Deaths in Hampstead, Holborn & St Pancras. Barnsley, South Yorkshire: Wharncliffe. ISBN 9781783408283. Archived from the original on 7 April 2023. Retrieved 7 March 2019.

- ^ "SAINT MATTHEW, SAINT PANCRAS: OAKLEY SQUARE, CAMDEN". Archived from the original on 7 August 2023. Retrieved 7 August 2023.

- ^ Wright, Thomas (1935). The life of Charles Dickens. London: Herbert Jenkins Limited. p. 50. Retrieved 2 June 2013.

- ^ Wright, Thomas (1935). The life of Charles Dickens. London: Herbert Jenkins Limited. p. 44. Retrieved 2 June 2013.

- ^ Wright, Thomas (1935). The life of Charles Dickens. London: Herbert Jenkins Limited. p. 52. Retrieved 2 June 2013.

- ^ "The Golden Dustmen of Dickens' time". 10 February 2016. Archived from the original on 15 November 2017. Retrieved 15 November 2017.

- ^ Roland Jeffery, Housing Happenings in Somers Town in Housing the Twentieth Century Nation, Twentieth Century Architecture No 9, 2008, ISBN 978-0-9556687-0-8

- ^ "Charlie Gillett – a reminiscence". Home thoughts from abroad. Alien thoughts from home. Jakartass.net. 2 April 2010. Archived from the original on 25 September 2013. Retrieved 26 May 2013.

- ^ Braid, Mary (16 August 1994). "Fear and loathing after 'racial' murder: Gangs of teenagers have vowed to avenge the death of a white schoolboy stabbed by a group of Asians in Somers Town, north London, on Saturday". The Independent. London. Archived from the original on 5 March 2016. Retrieved 7 May 2016.

- ^ McKie, John (1 November 1995). "Gang leader gets life for killing boy". The Independent. London. Archived from the original on 20 September 2018. Retrieved 7 May 2016.

- ^ Phil Emery; Pat Miller (2010). "Archaeological findings at the site of the St Pancras Burial Ground and its vicinity". London Archaeologist (Winter 2010/2011): 296.

- ^ PM backs groundbreaking medical research centre Archived 24 September 2008 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Deal secures £500m medical centre

- ^ French, Philip (23 August 2008). "Film of the week: Somers Town". The Observer. Archived from the original on 9 March 2016. Retrieved 4 October 2012.

- ^ "Pogues - Transmetropolitan lyrics | LyricsFreak". Archived from the original on 27 June 2022. Retrieved 27 June 2022.

- ^ "Markets in Camden". Camden. Camden London Borough Council. Archived from the original on 8 May 2016. Retrieved 7 May 2016.

- ^ Wroe, Simon (8 July 2010). "A summertime celebration of culture and art in Somers Town". Camden New Journal. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 4 October 2012.

- ^ "Five million passengers jump aboard for Paralympics". ITV News. 12 September 2012. Archived from the original on 13 September 2012. Retrieved 4 October 2012.

- ^ Jaksic, Ivan (2006). Andrés Bello: Scholarship and Nation-Building in Nineteenth-Century Latin America. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 75. ISBN 9780521027595. Archived from the original on 20 April 2023. Retrieved 2 February 2020.

- ^ Lamden, Tim (2 April 2015). "Green Party leader Natalie Bennett: 'That car crash interview will keep following me'". Ham&High. Archived from the original on 7 May 2016. Retrieved 7 May 2016.

- ^ a b c d e f Clarke, Linda (1992). "The population of Somers Town". Building Capitalism: Historical Change and the Labour Process in the Production of Built Environment. Oxford: Routledge. pp. 188–190. ISBN 978-0415687881. Retrieved 26 May 2013.

- ^ Martin, P. (May 1813). "The London Gazette". The Military Panorama or Officer's Companion for May 1830. London. p. 196.

- ^ Sinclair, Frederick (1947). "The Immortal of Doughty Street". St Pancras Journal (June 1947): 19. Archived from the original on 22 November 2012. Retrieved 29 June 2011.

- ^ Wheatley, Henry B. (1891). London, Past and Present: Its History, Associations, and Traditions. Vol. 3. London: John Murray. p. 268. Retrieved 26 May 2013.

- ^ House of Commons (21 February 1810). "Breach of Privilege—Mr. John Gale Jones". Parliamentary Debates (Hansard). Retrieved 18 May 2013.

- ^ Parolin, Christina (2010). Radical Spaces: Venues of Popular Politics in London, 1790 - C. 1845. Canberra: ANU E Press. pp. 1–2. ISBN 978-1921862007. Retrieved 28 May 2013.

- ^ Ray, Rob (1 November 2016). "London's anarchist HQ: 127 Ossulston St, 1894-1927". libcom..org. Archived from the original on 17 April 2021. Retrieved 12 May 2021.

- ^ Hibbert, Christopher, ed. (2008). The London Encyclopaedia. London: Macmillan. p. 850. ISBN 9781743282359. Retrieved 18 June 2015.

- ^ Anthony, Barry (2010). The King's Jester: The Life of Dan Leno, Victorian Comic Genius. London: I.B.Tauris & Co. ISBN 9780857731043. Retrieved 7 May 2016.

- ^ Crown, Sarah (11 October 2007). "Doris Lessing wins Nobel prize". The Guardian. London. Archived from the original on 6 January 2019. Retrieved 6 January 2019.

- ^ Rege, Josna (15 January 2012). "Doris Lessing and Me". Tell Me Another. Archived from the original on 6 January 2019. Retrieved 6 January 2019.

- ^ Mitan, Samuel (1894). . Dictionary of National Biography. Vol. 38.

- ^ . Dictionary of National Biography. Vol. 41. 1895.

- ^ Cave, Edward (1840). "Obituary". The Gentleman's Magazine, and Historical Chronicle for the year 1840. Vol. 14 New Series. London: William Pickering, John Bowyer Nichols and Son. p. 553. Archived from the original on 7 April 2023. Retrieved 25 May 2013.

- ^ "Meet the Sainsburys". Sainsbury's Archives. J Sainsbury plc. 2000. Archived from the original on 7 August 2020. Retrieved 2 February 2020.

- ^ Sylvanus Urban (Edward Cave) (October 1841). "Deaths - London and its vicinity". The Gentleman's Magazine. 170: 441.

- ^ Maxted, Ian (2001). "The London book trades 1775-1800: a preliminary checklist of members. Names S". Exeter Working papers in Book History. Exeter, UK: Devon Library Service. Archived from the original on 8 March 2012. Retrieved 20 September 2012.

- ^ Exhibition of the Royal Academy. London: The Academy. 1883. p. 62. Archived from the original on 7 April 2023. Retrieved 2 February 2020.

- ^ Wilson, Harriette (1909). The Memoirs of Harriette Wilson, Written by Herself. London: Eveleigh Nash. p. 89. Archived from the original on 22 April 2018. Retrieved 22 April 2018.

- ^ Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 28 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

- ^ Johnston, Kenneth R. (1998). "Philanthropy or Treason". The Hidden Wordsworth: Poet, Lover, Rebel, Spy. New York: W.W. Norton & Company. pp. 441–442. ISBN 0-393-04623-0. Retrieved 16 November 2018.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q Fairfield, Sheila (1983). The Streets of London – A dictionary of the names and their origins. Papermac.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u Bebbington, Gillian (1972). London street names. Batsford. ISBN 978-0-7134-0140-0.

- ^ a b c d e "British History Online: Somers Town". Archived from the original on 27 October 2017. Retrieved 27 October 2017.

- ^ a b "The Duke of Grafton". The Telegraph. London. 11 April 2011. Archived from the original on 27 February 2021. Retrieved 15 November 2017.