KGB: Difference between revisions

→Mode of operation: The duties described are that of a CIA Officer, not an Agent. |

m Cleaned up lead. |

||

| Line 39: | Line 39: | ||

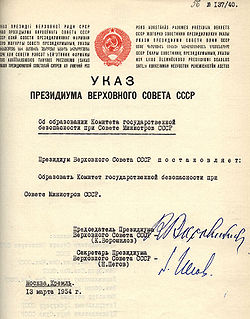

[[File:KGB first law.jpg|thumb|250px|Ukase of presidium of the Supreme Council of the USSR about organization of committee for State Security at the Council of Ministers of the USSR]] |

[[File:KGB first law.jpg|thumb|250px|Ukase of presidium of the Supreme Council of the USSR about organization of committee for State Security at the Council of Ministers of the USSR]] |

||

'''KGB''' is an [[initialism]] for ({{lang-rus|Комитет государственной безопасности (КГБ)|a=ru-KGB.ogg}}, ''Komitet gosudarstvennoy bezopasnosti'' (transliterated as '''Committee for State Security'''), was the main [[security agency]] for the [[Soviet Union]] from 1954 until its collapse in 1991. The KGB was formed in 1954 and attached to the [[Council of Ministers]], the committee was a direct successor of such preceding agencies as [[Cheka]], [[NKGB]], and [[Ministry for State Security (Soviet Union)|MGB]]. It was the chief government agency of "union-republican jurisdiction", acting as [[security agency|internal security]], [[Intelligence agency|intelligence]], and [[secret police]]. Similar agencies were instated in each of the republics of the Soviet Union aside from the [[Russian SFSR]] and consisted of many ministries, state committees and state commissions. |

|||

The KGB also has been considered a [[military service]] and was governed by army laws and regulations, similar to the [[Soviet Army]] or [[MVD]] [[Internal Troops]]. While most of the KGB archives remain classified, two on-line documentary sources are available.<ref name="Y">[http://www.yale.edu/annals/sakharov/sakharov_list.htm Yale.edu], The KGB File of Andrei Sakharov, Joshua Rubenstein and Alexander Gribanov eds., in Russian and English.</ref><ref name="B">[http://psi.ece.jhu.edu/~kaplan/IRUSS/BUK/GBARC/buk.html JHU.edu], archive of documents about [[Communist Party of the Soviet Union]] and KGB, collected by [[Vladimir Bukovsky]].</ref> Its main functions were foreign intelligence, counterintelligence, operative-investigatory activities, guarding the State Border of the USSR, guarding the leadership of the [[Central Committee of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union]] and the Soviet Government, organization and ensuring of government communications as well as fight against nationalism, dissent, and anti-Soviet activities. |

The KGB also has been considered a [[military service]] and was governed by army laws and regulations, similar to the [[Soviet Army]] or [[MVD]] [[Internal Troops]]. While most of the KGB archives remain classified, two on-line documentary sources are available.<ref name="Y">[http://www.yale.edu/annals/sakharov/sakharov_list.htm Yale.edu], The KGB File of Andrei Sakharov, Joshua Rubenstein and Alexander Gribanov eds., in Russian and English.</ref><ref name="B">[http://psi.ece.jhu.edu/~kaplan/IRUSS/BUK/GBARC/buk.html JHU.edu], archive of documents about [[Communist Party of the Soviet Union]] and KGB, collected by [[Vladimir Bukovsky]].</ref> Its main functions were foreign intelligence, counterintelligence, operative-investigatory activities, guarding the State Border of the USSR, guarding the leadership of the [[Central Committee of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union]] and the Soviet Government, organization and ensuring of government communications as well as fight against nationalism, dissent, and anti-Soviet activities. |

||

Revision as of 19:42, 11 August 2013

- For other meanings see KGB (disambiguation).

This article needs additional citations for verification. (May 2012) |

| Komitet gosudarstvennoy bezopasnosti KGB SSSR Комитет государственной безопасности КГБ СССР | |

The KGB Sword-and-Shield emblem. | |

Lubyanka Building in 1991 | |

| Agency overview | |

|---|---|

| Formed | 13 March 1954 |

| Preceding agencies | |

| Dissolved | 6 November 1991 (de facto) 3 December 1991 (de jure) |

| Superseding agency |

|

| Type | State committee of union-republican jurisdiction |

| Jurisdiction | Soviet Union |

| Headquarters | Lubyanskaya ploshchad, 2, Moscow, Russian SFSR |

| Motto | Loyalty to the party - Loyalty to motherland Верность партии - Верность Родине |

| Agency executive |

|

| Parent agency | Central Committee of the Party Council of Ministers of the USSR |

| Child agencies |

|

KGB is an initialism for (Russian: Комитет государственной безопасности (КГБ), Komitet gosudarstvennoy bezopasnosti (transliterated as Committee for State Security), was the main security agency for the Soviet Union from 1954 until its collapse in 1991. The KGB was formed in 1954 and attached to the Council of Ministers, the committee was a direct successor of such preceding agencies as Cheka, NKGB, and MGB. It was the chief government agency of "union-republican jurisdiction", acting as internal security, intelligence, and secret police. Similar agencies were instated in each of the republics of the Soviet Union aside from the Russian SFSR and consisted of many ministries, state committees and state commissions.

The KGB also has been considered a military service and was governed by army laws and regulations, similar to the Soviet Army or MVD Internal Troops. While most of the KGB archives remain classified, two on-line documentary sources are available.[1][2] Its main functions were foreign intelligence, counterintelligence, operative-investigatory activities, guarding the State Border of the USSR, guarding the leadership of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union and the Soviet Government, organization and ensuring of government communications as well as fight against nationalism, dissent, and anti-Soviet activities.

After breaking away from the Republic of Georgia in the early 1990s with Russian help, the self-proclaimed Republic of South Ossetia established its own KGB (keeping this unreformed name).[3]

Mode of operation

A 1983 Time magazine article reported that the KGB was the world's most effective information-gathering organization.[4] It operated legal and illegal espionage residencies in target countries where a legal resident gathered intelligence while based at the Soviet Embassy or Consulate, and, if caught, was protected from prosecution by diplomatic immunity. At best, the compromised spy either returned to the Soviet Union or was declared persona non grata and expelled by the government of the target country. The illegal resident spied, unprotected by diplomatic immunity, and worked independently of Soviet diplomatic and trade missions, (cf. the non-official cover CIA officer). In its early history, the KGB valued illegal spies more than legal spies, because illegal spies infiltrated their targets with greater ease. The KGB residency executed four types of espionage: (i) political, (ii) economic, (iii) military-strategic, and (iv) disinformation, effected with "active measures" (PR Line), counter-intelligence and security (KR Line), and scientific–technological intelligence (X Line); quotidian duties included SIGINT (RP Line) and illegal support (N Line).[5]

The KGB classified its spies as agents (intelligence providers) and controllers (intelligence relayers). The false-identity or legend assumed by a USSR-born illegal spy was elaborate, using the life of either a "live double" (participant to the fabrication) or a "dead double" (whose identity is tailored to the spy). The agent then substantiated his or her legend by living it in a foreign country, before emigrating to the target country, thus the sending of US-bound illegal residents via the Soviet embassy in Ottawa, Canada. Tradecraft included stealing and photographing documents, code-names, contacts, targets, and dead letter boxes, and working as a "friend of the cause" or agents provocateur, who would infiltrate the target group to sow dissension, influence policy, and arrange kidnappings and assassinations.[citation needed]

History

Mindful of ambitious spy chiefs—and after deposing Premier Nikita Khrushchev—Secretary Leonid Brezhnev and the CPSU knew to manage the next over-ambitious KGB Chairman, Aleksandr Shelepin (1958–61), who facilitated Brezhnev's palace coup d'état against Khrushchev in 1964 (despite Shelepin not then being in KGB). With political reassignments, Shelepin protégé Vladimir Semichastny (1961–67) was sacked as KGB Chairman, and Shelepin, himself, was demoted from chairman of the Committee of Party and State Control to Trade Union Council chairman.

In the 1980s, the glasnost liberalisation of Soviet society provoked KGB Chairman Vladimir Kryuchkov (1988–91) to lead the August 1991 Soviet coup d'état attempt to depose President Mikhail Gorbachev. The thwarted coup d'état ended the KGB on 6 November 1991. The KGB's successors are the secret police agency FSB (Federal Security Service of the Russian Federation) and the espionage agency SVR (Foreign Intelligence Service).

KGB in the US

The World War Interregnum

The GRU (military intelligence) recruited the ideological agents Julian Wadleigh and Alger Hiss, who became State Department diplomats in 1936. The NKVD's first US operation was establishing the legal residency of Boris Bazarov and the illegal residency of Iskhak Akhmerov in 1934.[6] Throughout, the Communist Party USA (CPUSA) and its General Secretary Earl Browder, helped NKVD recruit Americans, working in government, business, and industry.

Other important, low-level and high-level ideological agents were the diplomats Laurence Duggan and Michael Whitney Straight in the State Department, the statistician Harry Dexter White in the Treasury Department, the economist Lauchlin Currie (an FDR advisor), and the "Silvermaster Group", headed by statistician Greg Silvermaster, in the Farm Security Administration and the Board of Economic Warfare.[7] Moreover, when Whittaker Chambers, formerly Alger Hiss's courier, approached the Roosevelt Government—to identify the Soviet spies Duggan, White, and others—he was ignored. Hence, during the Second World War (1939–45)—at the Teheran (1943), Yalta (1945), and Potsdam (1945) conferences—Big Three Ally Joseph Stalin of the USSR, was better informed about the war affairs of his US and UK allies than they were about his.[8]

Soviet espionage succeeded most in collecting scientific and technologic intelligence about advances in jet propulsion, radar, and encryption, which impressed Moscow, but stealing atomic secrets was the capstone of NKVD espionage against Anglo–American science and technology. To wit, British Manhattan Project team physicist Klaus Fuchs (GRU 1941) was the main agent of the Rosenberg spy ring.[citation needed] In 1944, the New York City residency infiltrated the top secret Los Alamos National Laboratory in New Mexico, by recruiting Theodore Hall, a nineteen-year-old Harvard physicist.

During the Cold War

The KGB failed to rebuild most of its US illegal resident networks. The aftermath of the Second Red Scare (1947–57), McCarthyism, and the destruction of the CPUSA hampered recruitment. The last major illegal resident, Rudolf Abel ("Willie" Vilyam Fisher), was betrayed by his assistant, Reino Häyhänen, in 1957.

Recruitment then emphasised mercenary agents, an approach especially successful[citation needed][quantify] in scientific and technical espionage—because private industry practiced lax internal security, unlike the US Government. In late 1967, the notable KGB success was the walk-in recruitment of US Navy Chief Warrant Officer John Anthony Walker who individually and via the Walker Spy Ring for eighteen years enabled Soviet Intelligence to decipher some one million US Navy messages, and track the US Navy.[9]

In the late Cold War, the KGB was successful with intelligence coups in the cases of the mercenary walk-in recruits FBI counterspy Robert Hanssen (1979–2001) and CIA Soviet Division officer Aldrich Ames (1985-1994).[10]

KGB in the Soviet Bloc

It was Cold War policy for the KGB of the Soviet Union and the secret services of the satellite states to extensively monitor public and private opinion, internal subversion and possible revolutionary plots in the Soviet Bloc. In supporting those Communist governments, the KGB was instrumental in crushing the Hungarian Revolution of 1956, and the Prague Spring of "Socialism with a Human Face", in 1968 Czechoslovakia.

During the Hungarian revolt, KGB chairman Ivan Serov personally supervised the post-invasion "normalization" of the country. In consequence, KGB monitored the satellite-state populations for occurrences of "harmful attitudes" and "hostile acts;" yet, stopping the Prague Spring, deposing a nationalist Communist government, was its greatest achievement.

The KGB prepared the Red Army's route by infiltrating to Czechoslovakia many illegal residents disguised as Western tourists. They were to gain the trust of and spy upon the most outspoken proponents of Alexander Dubček's new government. They were to plant subversive evidence, justifying the USSR's invasion, that right-wing groups—aided by Western intelligence agencies—were going to depose the Communist government of Czechoslovakia. Finally, the KGB prepared hardline, pro-USSR members of the Communist Party of Czechoslovakia (CPC), such as Alois Indra and Vasil Biľak, to assume power after the Red Army's invasion.[citation needed]

The KGB's Czech success in the 1960s was matched with the failed suppression of the Solidarity labour movement in 1980s Poland. The KGB had forecast political instability consequent to the election of Archbishop of Kraków Karol Wojtyla as the first Polish Pope, John Paul II, whom they had categorised as "subversive" because of his anti-Communist sermons against the one-party PUWP régime. Despite its accurate forecast of crisis, the Polish United Workers' Party (PUWP) hindered the KGB's destroying the nascent Solidarity-backed political movement, fearing explosive civil violence if they imposed the KGB-recommended martial law. Aided by their Polish counterpart, the Służba Bezpieczeństwa (SB), the KGB successfully infiltrated spies to Solidarity and the Catholic Church[citation needed], and in Operation X co-ordinated the declaration of martial law with Gen. Wojciech Jaruzelski and the Polish Communist Party;[citation needed][dubious – discuss] however, the vacillating, conciliatory Polish approach blunted KGB effectiveness—and Solidarity then fatally weakened the Communist Polish government in 1989.

Suppressing internal dissent

During the Cold War, the KGB actively suppressed "ideological subversion"—unorthodox political and religious ideas and the espousing dissidents. In 1967, the suppression increased under new KGB Chairman Yuri Andropov.

After denouncing Stalinism in his secret speech On the Personality Cult and its Consequences (1956), Nikita Khrushchev lessened suppression of "ideological subversion". Resultantly, critical literature re-emerged, notably the novel One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich (1962), by Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn; however, after Khrushchev's deposition in 1964, Leonid Brezhnev reverted the State and KGB to actively harsh suppression—routine house searches to seize documents and the continual monitoring of dissidents. To wit, in 1965, such a search-and-seizure operation yielded Solzhenitsyn (code-name PAUK, "spider") manuscripts of "slanderous fabrications", and the subversion trial of the novelists Andrei Sinyavsky and Yuli Daniel; Sinyavsky (alias "Abram Tertz"), and Daniel (alias "Nikolai Arzhak"), were captured after a Moscow literary-world informant told KGB when to find them at home.

After suppressing the Prague Spring, KGB Chairman Andropov established the Fifth Directorate to monitor dissension and eliminate dissenters. He was especially concerned with Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn and Andrei Sakharov, "Public Enemy Number One".[11] Andropov failed to expel Solzhenitsyn before 1974; but did internally exile Sakharov to Gorky in 1980. KGB failed to prevent Sakharov's collecting his Nobel Peace Prize in 1975, but did prevent Yuri Orlov collecting his Nobel Prize in 1978; Chairman Andropov supervised both operations.

KGB dissident-group infiltration featured agents provocateur pretending "sympathy to the cause", smear campaigns against prominent dissidents, and show trials; once imprisoned, the dissident endured KGB interrogators and sympathetic informant cell-mates. In the event, Mikhail Gorbachev's glasnost policies lessened persecution of dissidents; he was effecting some of the policy changes they had been demanding since the 1970s.[12]

Notable operations

- With the Trust Operation (1921–1926), the OGPU successfully deceived some leaders of the right-wing, counter-revolutionary White Guards back to the USSR for execution.

- NKVD infiltrated and destroyed Trotskyist groups; in 1940, the Spanish agent Ramón Mercader assassinated Leon Trotsky in Mexico City.

- KGB favoured active measures (e.g. disinformation), in discrediting the USSR's enemies.

- For war-time, KGB had ready sabotage operations arms caches in target countries.

In the 1960s, acting upon the information of KGB defector Anatoliy Golitsyn, the CIA counter-intelligence chief James Jesus Angleton believed KGB had moles in two key places—the counter-intelligence section of CIA and the FBI's counter-intelligence department—through whom they would know of, and control, US counter-espionage to protect the moles and hamper the detection and capture of other Communist spies. Moreover, KGB counter-intelligence vetted foreign intelligence sources, so that the moles might "officially" approve an anti-CIA double agent as trustworthy. In retrospect, the captures of the moles Aldrich Ames and Robert Hanssen proved that Angleton, though ignored as over-aggressive, was correct, despite costing him his job at CIA, which he left in 1975.[citation needed]

In the mid-1970s, the KGB tried to secretly buy three banks in northern California to gain access to high-technology secrets. Their efforts were thwarted by the CIA. The banks were Peninsula National Bank in Burlingame, the First National Bank of Fresno, and the Tahoe National Bank in South Lake Tahoe. These banks had made numerous loans to advanced technology companies and had many of their officers and directors as clients. The KGB used the Moscow Narodny Bank Limited to finance the acquisition, and an intermediary, Singaporean businessman Amos Dawe, as the frontman.[13]

August 1991 Coup

On August 18, 1991 the Chairman of the KGB Vladimir Kryuchkov and 7 other Soviet leaders, the State Committee on the State of Emergency, attempted to overthrow the government of the Soviet Union. The purpose of the attempted coup d'état was to preserve the integrity of the Soviet Union and the constitutional order. President Mikhail Gorbachev was arrested and ineffective attempts made to seize power. Within two days, by 20 August 1991, the attempted coup collapsed.

Organization of the KGB

Republican affiliations

The republican affiliation offices almost completely duplicated the structural organization of the main KGB.

- KGB of Belarus / KDB of Belarus (see State Security Committee of the Republic of Belarus)

- KGB of Ukraine / KDB of Ukraine (see Committee for State Security (Ukraine))

- KGB of Moldova / CSS of Moldova

- KGB of Estonia / RJK of Estonia

- KGB of Latvia / VDK of Latvia

- KGB of Lithuania / VSK of Lithuania

- KGB of Georgia

- KGB of Armenia

- KGB of Azerbaijan / DTK of Azerbaijan

- KGB of Kazakhstan

- KGB of Kyrgyzstan

- KGB of Uzbekistan

- KGB of Turkmenistan

- KGB of Tajikistan

- KGB of Russia (created in 1991)

Leadership

The Chairman of the KGB, First Deputy Chairmen (1–2), Deputy Chairmen (4–6). Its policy Collegium comprised a chairman, deputy chairmen, directorate chiefs, and republican KGB chairmen.

The Directorates

- First Chief Directorate (Foreign Operations) – foreign espionage. (now the Foreign Intelligence Service or SVR in Russian)

- Second Chief Directorate – counter-intelligence, internal political control.

- Third Chief Directorate (Armed Forces) – military counter-intelligence and armed forces political surveillance.

- Fourth Directorate (Transportation security)

- Fifth Chief Directorate – censorship and internal security against artistic, political, and religious dissension; renamed "Directorate Z", protecting the Constitutional order, in 1989.

- Sixth Directorate (Economic Counter-intelligence, industrial security)

- Seventh Directorate (Surveillance) – of Soviet nationals and foreigners.

- Eighth Chief Directorate – monitored-managed national, foreign, and overseas communications, cryptologic equipment, and research and development.

- Ninth Directorate (Guards and KGB Protection Service) - The 40,000-man uniformed bodyguard for the CPSU leaders and families, guarded critical government installations (nuclear weapons, etc.), operated the Moscow VIP subway, and secure Government–Party telephony. Pres. Yeltsin transformed it to the Federal Protective Service (FPS).

- Fifteenth Directorate (Security of Government Installations)

- Sixteenth Directorate (SIGINT and communications interception) - operated the national and government telephone and telegraph systems.

- Border Guards Directorate responsible for the USSR's border troops.

- Operations and Technology Directorate – research laboratories for recording devices and Laboratory 12 for poisons and drugs.

Other Units

- KGB Personnel Department

- Secretariat of the KGB

- KGB Technical Support Staff

- KGB Finance Department

- KGB Archives

- KGB Irregulars

- Administration Department of the KGB, and

- The CPSU Committee.

- KGB Spetsnaz (special operations) units such as:

- The Alpha Group

- The Vympel, etc.

- Kremlin Guard Force for the Presidium, et al., then became the FPS.

List of chairmen

| Chairman | Dates |

|---|---|

| Ivan Aleksandrovich Serov | 1954–58 |

| Aleksandr Nikolayevich Shelepin | 1958–61 |

| Vladimir Yefimovich Semichastny | 1961–67 |

| Yuri Vladimirovich Andropov | 1967–1982 (Jan-May) |

| Vitali Vasilyevich Fedorchuk | 1982 (May–Dec) |

| Viktor Mikhailovich Chebrikov | 1982–88 |

| Vladimir Aleksandrovich Kryuchkov | 1988–91 |

| Vadim Viktorovich Bakatin | 1991 (Aug–Nov) |

Insignia

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

Komsomol KGB

See also

- Active measures

- Chronology of Soviet secret police agencies

- CIA

- Eastern Bloc politics

- FBI

- Federal Agency of Government Communications and Information

- Federal Protective Service

- Federal Security Service (KGB successor)

- Foreign Intelligence Service

- History of Soviet espionage

- Index of Soviet Union-related articles

- ISI

- KGB victim memorials

- Ministry of Internal Affairs

- Mitrokhin Archive

- Numbers station

- Presidential Security Service

- RAW

- Sanzo Nosaka

- SMERSH

- Venona

- Department of Homeland Security

- World Peace Council

Notes

- ^ Yale.edu, The KGB File of Andrei Sakharov, Joshua Rubenstein and Alexander Gribanov eds., in Russian and English.

- ^ JHU.edu, archive of documents about Communist Party of the Soviet Union and KGB, collected by Vladimir Bukovsky.

- ^ [1]

- ^ Eyes of the Kremlin

- ^ The Sword and the Shield (1999) p. 38

- ^ The Sword and the Shield (1999) p. 104

- ^ The Sword and the Shield (1999) pp. 104–5

- ^ The Sword and the Shield (1999) p. 111

- ^ The Sword and the Shield (1999) p. 205

- ^ The Sword and the Shield (1999) p. 435

- ^ The Sword and the Shield (1999) p. 325

- ^ The Sword and the Shield (1999) p. 561

- ^ Tolchin, Martin (16 February 1986). "Russians sought U.S. banks to gain high-tech secrets". New York Times.

References

- Christopher Andrew and Vasili Mitrokhin, The Mitrokhin Archive: The KGB in Europe and the West, Gardners Books (2000) ISBN 0-14-028487-7; Basic Books (1999) ISBN 0-465-00310-9; trade (2000) ISBN 0-465-00312-5

- Christopher Andrew and Vasili Mitrokhin, The World Was Going Our Way: The KGB and the Battle for the Third World, Basic Books (2005) ISBN 0-465-00311-7

- John Barron, KGB: The Secret Work of Soviet Secret Agents, Reader's Digest Press (1974) ISBN 0-88349-009-9

- Amy Knight, The KGB: Police and Politics in the Soviet Union, Unwin Hyman (1990) ISBN 0-04-445718-9

- Richard C.S. Trahair and Robert Miller, Encyclopedia of Cold War Espionage, Spies, and Secret Operations, Enigma Books (2009) ISBN 978-1-929631-75-9

Further reading

- Солженицын, А.И. (1990). Архипелаг ГУЛАГ: 1918 - 1956. Опыт художественного исследования. Т. 1 - 3. Москва: Центр "Новый мир". (in Russian)

- Yevgenia Albats and Catherine A. Fitzpatrick, The State Within a State: The KGB and Its Hold on Russia — Past, Present, and Future Farrar Straus Giroux (1994) ISBN 0-374-52738-5.

- John Barron, KGB: The Secret Works of Soviet Secret Agents Bantam Books (1981) ISBN 0-553-23275-4

- Vadim J. Birstein. The Perversion Of Knowledge: The True Story of Soviet Science. Westview Press (2004) ISBN 0-8133-4280-5

- John Dziak Chekisty: A History of the KGB, Lexington Books (1988) ISBN 978-0-669-10258-1

- Sheymov, Victor (1993). Tower of Secrets. Naval Institute Press. p. 420. ISBN 1-55750-764-3.

- Template:Ru icon Бережков, Василий Иванович (2004). Руководители Ленинградского управления КГБ : 1954-1991. Санкт-Петербург: Выбор, 2004. ISBN 5-93518-035-9

- Кротков, Юрий (1973). «КГБ в действии». Published in «Новый журнал» №111, 1973 (in Russian)

- Рябчиков, С.В. (2004). Размышляя вместе с Василем Быковым // Открытый мiръ, № 49, с. 2-3. (in Russian)(ФСБ РФ препятствует установлению мемориальной доски на своем здании, в котором ВЧК - НКВД совершала массовые преступления против человечности. Там была установлена "мясорубка", при помощи которой трупы сбрасывались чекистами в городскую канализацию.)

http://independent.academia.edu/SergeiRjabchikov/Papers/696439/Razmyshlyaya_vmeste_s_Vasilem_Bykovym

- Рябчиков, С.В. (2008). Великий химик Д.И. Рябчиков // Вiсник Мiжнародного дослiдного центру "Людина: мова, культура, пiзнання", т. 18(3), с. 148-153. (in Russian) (об организации КГБ СССР убийства великого русского ученого)

- Рябчиков, С.В. (2011). Заметки по истории Кубани (материалы для хрестоматии) // Вiсник Мiжнародного дослiдного центру "Людина: мова, культура, пiзнання", 2011, т. 30(3), с. 25-45. (in Russian)

External links

- For Cold War KGB activity in the US, see Alexander Vassiliev's Notebooks from the Cold War International History Project (CWIHP)

- Soviet Technospies from the Dean Peter Krogh Foreign Affairs Digital Archives

- KGB Information Center, Federation of American Scientists

- Viktor M. Chebrikov et al., eds. Istoriya sovetskikh organov gosudarstvennoi bezopasnosti ("History of the Soviet Organs of State Security"). (1977), www.fas.harvard.edu

- Template:Ru icon Slaves of KGB. 20th Century. The religion of betrayal, by Yuri Shchekochikhin