Ernest Hemingway: Difference between revisions

→References: add template here |

removing more subjective information |

||

| Line 11: | Line 11: | ||

|deathdate = {{death date and age|1961|7|2|1899|7|21|mf=y}} |

|deathdate = {{death date and age|1961|7|2|1899|7|21|mf=y}} |

||

|deathplace = [[Ketchum, Idaho]], United States |

|deathplace = [[Ketchum, Idaho]], United States |

||

|occupation = |

|occupation = |

||

|genre = |

|||

|genre = [[War novel|War]], [[Romance novel|Romance]] |

|||

|movement = |

|movement = |

||

|spouse = [[Elizabeth Hadley Richardson]] (1921–1927)<br /> [[Pauline Pfeiffer]] (1927–1940)<br /> [[Martha Gellhorn]] (1940–1945)<br /> [[Mary Welsh Hemingway]] (1946–1961) |

|spouse = [[Elizabeth Hadley Richardson]] (1921–1927)<br /> [[Pauline Pfeiffer]] (1927–1940)<br /> [[Martha Gellhorn]] (1940–1945)<br /> [[Mary Welsh Hemingway]] (1946–1961) |

||

|children = [[Jack Hemingway]] (1923–2000)<br /> Patrick Hemingway (1928–)<br /> [[Gregory Hemingway]] (1931–2001) |

|children = [[Jack Hemingway]] (1923–2000)<br /> Patrick Hemingway (1928–)<br /> [[Gregory Hemingway]] (1931–2001) |

||

|influences = |

|||

|influences = [[Knut Hamsun]], [[Mark Twain]], [[Rudyard Kipling]], [[Theodore Roosevelt]], [[Ivan Turgenev]], [[Leo Tolstoy]], [[Sherwood Anderson]], [[Pío Baroja]], [[Fyodor Dostoevsky]], [[Theodore Dreiser]], [[Ring Lardner]], [[Gertrude Stein]], [[Ezra Pound]], [[Stephen Crane]], [[Joseph Conrad]] |

|||

|influenced = |

|||

|influenced = [[Charles Bukowski]], [[Cormac McCarthy]], [[Raymond Carver]], [[Bret Easton Ellis]], [[Richard Ford]], [[Jack Kerouac]], [[Elmore Leonard]], [[Harold Pinter]], [[J. D. Salinger]], [[John Updike]], [[Hunter S. Thompson]], [[Colm Tóibín]], [[Norman Mailer]], [[Mohsin Hamid]], [[Richard Brautigan]], [[K.J. Stevens]], [[Ken Kesey]], [[Italo Calvino]], [[Joyce Carol Oates]] |

|||

| religion = |

| religion = |

||

| awards = {{awd|[[Nobel Prize in Literature]]|1954|[[Pulitzer Prize for Fiction]]|1953}} |

| awards = {{awd|[[Nobel Prize in Literature]]|1954|[[Pulitzer Prize for Fiction]]|1953}} |

||

| signature = Ernest Hemingway Signature.svg |

| signature = Ernest Hemingway Signature.svg |

||

Revision as of 01:02, 17 January 2010

Ernest Hemingway | |

|---|---|

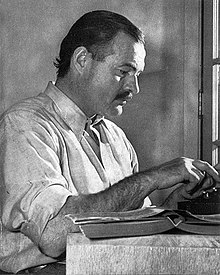

Hemingway in 1939 | |

| Nationality | American |

| Notable awards | Nobel Prize in Literature 1954 Pulitzer Prize for Fiction – 1953 |

| Spouse | Elizabeth Hadley Richardson (1921–1927) Pauline Pfeiffer (1927–1940) Martha Gellhorn (1940–1945) Mary Welsh Hemingway (1946–1961) |

| Children | Jack Hemingway (1923–2000) Patrick Hemingway (1928–) Gregory Hemingway (1931–2001) |

| Signature | |

Ernest Miller Hemingway (July 21, 1899 – July 2, 1961) was an American writer and journalist. During his lifetime he wrote and had published seven novels; six collections of short stories; and two works of non-fiction. Since his death three novels, four collections of short stories, and three non-fiction autobiographical works have been published. Hemingway received the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1954.

Hemingway was born and raised in Oak Park, Illinois. After high school he worked as a reporter but within months he left for the Italian front to be an ambulance driver in World War I. He was seriously injured and returned home within the year. He married his first wife Hadley Richardson in 1922 and moved to Paris, where he worked as a foreign correspondent. During this time Hemingway met, and was influenced by, writers and artists of the 1920s expatriate community known as the "Lost Generation". In 1924 Hemingway wrote his first novel, The Sun Also Rises.

In the late 1920s, Hemingway divorced Hadley, married his second wife Pauline Pfeiffer, and moved to Key West, Florida. In 1937 Hemingway went to Spain as a war correspondent to cover the Spanish Civil War. After the war he divorced Pauline, married his third wife Martha Gellhorn, wrote For Whom the Bell Tolls, and moved to Cuba. Hemingway covered World War II in Europe and he was present at Operation Overlord. Later he was in Paris during the liberation of Paris. After the war, he divorced again, married his fourth wife Mary Welsh Hemingway, and wrote Across the River and Into the Trees. Two years later, The Old Man and the Sea was published in 1952. Nine years later, after moving from Cuba to Idaho, he committed suicide in the summer of 1961.

Hemingway produced most of his work between the mid 1920s and the mid 1950s, though a number of unfinished works were published posthumously. Hemingway's distinctive writing style is characterized by economy and understatement, and had a significant influence on the development of twentieth-century fiction writing. His protagonists are typically stoical men who exhibit an ideal described as "grace under pressure." Many of his works are now considered classics of American literature. During his lifetime, Hemingway's popularity peaked after the publication of The Old Man and the Sea. His impact on American literature has been considerable. For example, J.D. Salinger admired Hemingway's style and methods of writing.

Biography

Early life and World War I

Ernest Miller Hemingway was born on July 21, 1899 in Oak Park, Illinois, a suburb of Chicago.[1] Hemingway was the first son and the second child born to Clarence Edmonds "Doc Ed" Hemingway—a country doctor, and Grace Hall Hemingway. The Hemingways lived in a six-bedroom Victorian house built by Hemingway's maternal grandfather, Ernest Miller Hall, an English immigrant and Civil War veteran who lived with the family. Hemingway was named after his grandfather, although he disliked his name, and "associated it with the naive, even foolish hero of Oscar Wilde's play The Importance of Being Earnest".[2]

Hemingway's mother, who wanted to be an opera singer, earned money with voice and music lessons. She was domineering and narrowly religious, mirroring the strict Protestant ethic of Oak Park. The town, according to Hemingway, had "wide lawns and narrow minds".[1] Her insistence that he learn the cello became a "source of conflict", but he later admitted the music lessons were useful to his writing as in the "contrapunctal structure of For Whom the Bell Tolls ".[3] The family owned a summer home called Windemere on Walloon Lake, near Petoskey, Michigan where they spent the summers.[1][4] Hemingway learned to hunt, fish, and camp in the woods and lakes of Northern Michigan. His early experiences with nature instilled a passion for outdoor adventure, living in remote or isolated areas, hunting and fishing, and became permanent interests.[4]

Hemingway attended Oak Park and River Forest High School from 1913 until 1917. There he was involved with sports: boxing, track, water polo, and football. He showed talent in English classes and was on the debate team.[5] He wrote and edited the "Trapeze" and "Tabula" (the school's newspaper and yearbook), where he imitated the language of sportswriters, and sometimes used the pen name Ring Lardner, Jr., a nod to his literary hero Ring Lardner of the Chicago Tribune who used the byline "Line O'Type".[6][7] After high school, Hemingway was hired as a cub reporter at The Kansas City Star, and like Mark Twain, Stephen Crane, Theodore Dreiser and Sinclair Lewis he worked as a journalist prior to becoming a novelist.[8] Although he worked at the newspaper for only six months—from October 17, 1917 to April 30, 1918—he relied on the Star's style guide as a foundation for his writing: "Use short sentences. Use short first paragraphs. Use vigorous English. Be positive, not negative."[9]

Hemingway volunteered to become an ambulance driver for the Red Cross in Italy early in 1918.[10] He left New York in May, and arrived in Paris as the city was under bombardment from German artillery.[11] By June he was stationed at the Italian Front.[12] On July 8 he was seriously wounded by mortar fire as he ran an errand to the canteen.[12][13] Despite his wounds, Hemingway carried an Italian soldier to safety, for which he was honored with the Italian Silver Medal of Bravery.[12][14] Still only eighteen, Hemingway said of the incident: "When you go to war as a boy you have a great illusion of immortality. Other people get killed; not you....Then when you are badly wounded the first time you lose that illusion and you know it can happen to you."[12] He had shrapnel wounds to both legs, had an operation at a distribution center, spent five days at a field hospital, and was transferred to the Red Cross hospital in Milan for recuperation.[15] He spent six months in the hospital where he met and fell in love with Agnes von Kurowsky, a Red Cross nurse seven years older than he.[16] Agnes and Hemingway planned to marry; however, she became engaged to an Italian officer in March 1919.[17] Biographer Jeffrey Meyers claims Hemingway was devastated by Agnes' rejection, and in future relationships he followed a pattern of abandoning a wife before she abandoned him.[18]

Toronto, Chicago and Paris

Hemingway returned home in early 1919, and spent the following summer in Michigan, fishing and camping with high school friends. The summer became the genesis for his Nick Adams' story "Big Two-Hearted River".[12] He then moved to Toronto and began writing for the Toronto Star Weekly where he worked as a freelancer, staff writer, and foreign correspondent[19] In the fall of 1920, after having spent the summer in Michigan,[19] he moved to Chicago for a short period while still filing stories for the Toronto Star. He also worked as associate editor of the monthly journal Co-operative Commonwealth.[20] Hemingway met Hadley Richardson in Chicago. She was eight years older than he (and one year older than Agnes).[21] They married on September 3, 1921; in November he became foreign correspondent for the Toronto Star and the couple left for Paris.[22]

Sherwood Anderson gave Hemingway letters of introduction to Gertrude Stein and other writers he had recently met in Paris.[23] Stein, who became Hemingway's mentor for a period, and introduced him to the "Parisian Modern Movement" in the Montparnasse Quarter, referred to the expatriate artists as the "Lost Generation".[24] The group included writers and artists such "Ezra Pound, Gertrude Stein, Sylvia Beach, James Joyce, Max Eastman, Lincoln Steffens and Wyndham Lewis [and] the painters Miró and Picasso."[1] Eventually Hemingway withdrew from Stein's influence and their relationship deteriorated to a literary quarrel that spanned decades.[25] Hemingway and Ezra Pound forged a friendship; and Pound mentored the young writer in whom he recognized a natural talent. They met in February 1922, toured Italy together in 1923, and lived on the same street in 1924.[26] Sylvia Beach, who published James Joyce's Ulysses, owned the bookshop Shakespeare and Company that was a popular gathering place for writers, where Hemingway met Joyce in March 1922. The two writers frequently embarked on "alcoholic sprees."[27]

Hemingway covered the Greco-Turkish War for the Toronto Star, where he witnessed the burning of Smyrna.[28] He also wrote travel pieces such as "Tuna Fishing in Spain", "Trout Fishing All Across Europe: Spain Has the Best, Then Germany", and he wrote about bullfighting—"Pamplona in July; World's Series of Bull Fighting a Mad, Whirling Carnival".[28] In December 1922 Hemingway was devastated when Hadley lost a suitcase filled with his manuscripts at the Gare de Lyons as she was travelling from Paris to Geneva to meet him.[29] When Hadley became pregnant in 1923 they returned to Toronto where their son John Hadley Nicanor was born on October 10, 1923.[30] They returned to Paris at the beginning of the new year in 1924, and Hemingway decided to stop writing for the Toronto Star, recreate the lost stories, and begin writing for publication.[31] Also in 1924 Hemingway assisted Ford Madox Ford in editing The Transatlantic Review. Ford published works by Pound, John Dos Passos, and Gertrude Stein, as well as some of Hemingway's early stories such as "Indian Camp".[32] When Hemingway's first collection of short stories, "In Our Time" was published in 1925, the dust jacket included comments from Ford.[33] Six months earlier, Hemingway had met F. Scott Fitzgerald, and they began a friendship of "admiration and hostility."[34]

In the summer of 1925, Hemingway and Hadley went on their annual trip to Pamplona to the Festival of San Fermín accompanied by a group of American and British ex-patriates.[35] The events of the trip inspired Hemingway's first novel, The Sun Also Rises. He finished the first draft in two months. During the next six months he revised the manuscript as his marriage to Hadley began to disintegrate. Scribner's published The Sun Also Rises in October 1926.[36] Hemingway divorced Hadley in January 1927, and in May married Pauline Pfeiffer.[37] Pfeiffer wrote for Vanity Fair and worked for Vogue in Paris.[38][39] Hemingway converted to Catholicism to marry Pauline.[40] Men Without Women, a collection of short stories, containing The Killers, was published in October 1927.[41] By the end of the year Pauline was pregnant, and on the recommendation of Dos Passos, Hemingway and Pauline moved to Key West. After his departure from Paris, Hemingway "never again lived in a big city."[42]

Key West and the Caribbean

Hemingway's second son Patrick was born in Kansas City on June 28, 1928. Pauline's labor was difficult and she had a Caesarean.[43] For a time they lived with Pauline's parents at the Pfeiffer House in Piggott, Arkansas, where Hemingway worked on A Farewell to Arms. After Patrick's birth Hemingway travelled to Wyoming, Massachusetts and New York. That December, Hemingway's father shot himself with his own father's (Hemingway's grandfather's) American Civil War pistol, having suffered ill health, depression and financial difficulties.[43][44][1]

Hemingway continued to travel extensively, returning to France and Spain in the summer of 1929 to gather material for Death in the Afternoon. A Farewell to Arms was published in September of that year.[45] Hemingway spent winters in Key West, and summers in Wyoming where he found "the most beautiful country he had seen in the American West" and where the hunting included deer, elk, and grizzly bear.[46] His third son, Gregory, was born on November 12, 1931.[47] Also In 1931, Pauline's uncle bought the couple a house.[1][48] In a converted den on the second floor of the "carriage house" Hemingway had a space to work.[49] While in Key West he also spent time fishing the waters around the Dry Tortugas with his longtime friend Waldo Peirce, and at Sloppy Joe's.[50]

In 1933, Hemingway and Pauline travelled to Africa for ten weeks. The trip provided material for Green Hills of Africa, and the short stories "The Snows of Kilimanjaro" and "The Short Happy Life of Francis Macomber".[51][52] He visited Mombasa, Nairobi, and Machakos in Kenya, then Tanganyika on safari, where he hunted in the Serengeti, around Lake Manyara and west and southeast of the present-day Tarangire National Park. He contracted amoebic dysentery causing a prolapsed intestine and he was evacuated to Nairobi by plane, an experience reflected in "The Snows of Kilimanjaro". On this trip Hemingway's guide was Philip Hope Percival, who had guided Theodore Roosevelt on his 1909 safari. Hemingway began writing Green Hills of Africa as soon as he returned, which was published in 1935.[53]

Back in Key West, Hemingway bought a boat in 1934, named it the "Pilar", and began sailing the Caribbean.[54] In 1935 he discovered Bimini where he spent considerable time.[51] During this period he also worked on To Have and Have Not, published in 1937 when he was in Spain, and the only novel he wrote during the 1930s.[55]

Spanish Civil War and World War II

In 1937 Hemingway reported on the Spanish Civil War for the North American Newspaper Alliance (NANA).[56] He arrived in France in March, and in Spain ten days later with Dutch filmmaker Joris Ivens.[57] Ivens was filming The Spanish Earth working with John Dos Passos as screen writer. However, Dos Passos wanted to leave because his friend José Robles had been arrested (and was later executed), so he passed the screen-writing work over to Hemingway.[58] At that time Dos Passos changed his opinion of the republicans, causing a rift between himself and Hemingway who spread a rumor that Dos Passos was a coward when he left Spain.[59][60] Journalist Martha Gellhorn, whom Hemingway had met in Key West in 1936, joined him in Spain.[12][61] Hemingway and Gellhorn continued their relationship during the war, until Hemingway divorced Pauline in 1940. Pauline, a devout Catholic, sided with the pro-Catholic nationalists; whereas Hemingway supported the republicans.[1] Hemingway wrote The Fifth Column, his only piece of drama, during the bombardment of Madrid in 1937.[62][63] His involvement with the republicans and the International Brigade may have gone so far as teaching young Spaniards how to use rifles.[64] In 1938, after having returned home to Key West for a few months, Hemingway returned to Spain and was present at the Battle of the Ebro, the last republican stand. With fellow British and American journalists, Hemingway rowed the group across the river, some of the last to leave the battle.[65][66] A later letter to XI International Brigade's commander Hans Kahle gives the impression, as if he had seen the war as an exciting adventure.[67]

Hemingway and Martha Gellhorn moved to Cuba in 1939, and in 1940 bought the "Finca Vigia" which they had been renting.[68] A few months later Hemingway divorced Pauline and married Martha.[69] During that period he wrote For Whom the Bell Tolls, which he began in March 1939, finished in July 1940, and which was published in October 1940.[70] As he wrote For Whom the Bell Tolls he travelled from Cuba to Wyoming to Sun Valley, Idaho.[71] He also changed the location of his homes, as he had after his split with Hadley, moving his primary summer residence to Ketchum, Idaho, just outside of the newly built resort Sun Valley, having already moved his winter residence from Key West to Cuba.[72] In January 1941, Martha was sent to China on assignment for Collier's magazine, and Hemingway accompanied her.[73] Although Hemingway wrote dispatches for PM, he had little affinity for China.[74]

When he returned to Cuba, after the beginning of World War II, Hemingway refitted the Pilar to hunt down German submarines.[12] From June to December 1944, he was in Europe,[75] and was present at the D-Day landing.[76] He then attached himself to "the 22nd Regiment commanded by Col. Charles "Buck" Lanaham as it drove toward Paris", and he also had a small band of village militia in Rambouillet outside of Paris.[77] Of Hemingway's exploits, a war historian remarks: " 'Hemingway got into considerable trouble playing infantry captain to a group of Resistance people that he gathered because a correspondent is not supposed to lead troops, even if he does it well.' "[12] On August 25 he was present at the liberation of Paris, though the assertion that he was first in the city, or that he liberated the Ritz is considered part of the Hemingway legend.[78][79] While in Paris he attended a reunion hosted by Sylvia Beach and also made up his long feud with Gertrude Stein.[80] Hemingway was present at heavy fighting in the Hürtgenwald at the end 1944.[81]

When Hemingway arrived in Europe, he met Time correspondent Mary Welsh in London.[82] During the war his marriage to Martha disintegrated and the last time he saw her was in March 1945 as he was preparing to return to Cuba.[83] In 1947 Hemingway was awarded a Bronze Star for his bravery during World War II. His valor for having been " 'under fire in combat areas in order to obtain an accurate picture of conditions,' " was recognized, with the commendation that " 'Through his talent of expression, Mr. Hemingway enabled readers to obtain a vivid picture of the difficulties and triumphs of the front-line soldier and his organization in combat.' "[12]

Cuba

Hemingway married Mary Welsh in March 1946, and five months later she suffered an ectopic pregnancy.[84] Hemingway and Mary suffered a series of accidents after the war: in 1945 Hemingway had a car accident and injured his knee, and over the next five years Mary suffered a number of broken bones.[84] In 1947 his sons Patrick and Gregory had a car accident and Gregory suffered a serious illness as a consequence.[84] Also the 1940s was a decade when many of Hemingway's friends died. In 1939 Yeats and Ford Madox Ford died; in 1940 Scott Fitzgerald died; in 1941 Sherwood Anderson and James Joyce died; in 1946 Gertrude Stein died; and the following year in 1947, Max Perkins, Hemingway's long time editor and friend, died.[85]

Hemingway began to suffer from ill health: headaches, high blood pressure, weight problems, depression, and eventually diabetes, although he was also working on the manuscript of The Garden of Eden.[86] In 1948 Hemingway and Mary travelled to Europe, and in Italy he visited the site of his World War I accident.[87] Soon thereafter he began work on Across the River and Into the Woods, which he worked on through 1949[87] and published it in 1950.[88] In 1951 he completed the draft of Old Man and the Sea in eight weeks and considered it "the best I can write ever for all of my life."[86] The Old Man and the Sea won the Pulitzer Prize in May 1952, a month before he left for his second trip to Africa.[89] In Africa he was seriously injured in two successive plane crashes: he sprained his right shoulder, arm, and left leg; had a concussion; temporarily lost vision in his left eye and the hearing in his left ear; suffered paralysis of the spine; had a crushed vertebra, ruptured liver, spleen and kidney; and sustained first degree burns on his face, arms, and leg. Some American newspapers published his obituary, believing he had been killed.[90] A month later he was again badly injured in a bushfire accident, which left him with second degree burns on his legs, front torso, lips, left hand and right forearm.[91]

In October 1954, Hemingway received the Nobel Prize in Literature.[92] Politely he mentioned Carl Sandburg and Isak Dinesen, who in his opinion, deserved the prize.[92] The prize money was welcome he told reporters. [92] Because he was in pain as a result of the African accidents, and he had recently returned home to Cuba after an absence of almost a full year, Hemingway chose not to travel to Stockholm to accept the prize in person.[93] Instead he sent a speech to be read in which he defines the writer's life: "Writing, at its best, is a lonely life. Organizations for writers palliate the writer's loneliness but I doubt if they improve his writing. He grows in public stature as he sheds his loneliness and often his work deteriorates. For he does his work alone and if he is a good enough writer he must face eternity, or the lack of it, each day."[94]

During the mid-1950s, Hemingway was often ill and he was bedridden from late 1956 to early 1957.[95] The Finca Vigia became crowded with guests and tourists.[96] He became disaffected with life in Cuba and considered a permanent move to Idaho.[97] In 1959 he bought a home, overlooking the Big Wood River, outside of Ketchum and left Cuba, although he apparently remained on easy terms with the Castro government, going so far as telling the New York Times he was "delighted" with Castro's overthrow of Havana.[97][98] However, the Hemingway account "The Shot" is used by Cabrera Infante and others as evidence of conflict between Hemingway and Fidel Castro dating back to 1948 and the killing of "Manolo" Castro, a friend of Hemingway.[99] In 1960, he left Cuba and Finca Vigía for the last time. The Cuban government claims that after her husband's death, Mary Welsh Hemingway deeded the home to the Cuban government, which made it into a museum devoted to the author.[100] In fact, the house was appropriated after the Bay of Pigs invasion, complete with Hemingway's collection of "four to six thousand books".[101] The Hemingways lost their home, and were forced to leave art and manuscripts in a bank vault in Havana.[101]

Idaho and suicide

In 1957 he began A Moveable Feast, which he worked on in Cuba and Idaho from 1957 to 1960.[102][103] In 1959, his passion for bullfighting was renewed when he spent the summer in Spain for a series of bullfight articles he was to write for Life Magazine.[104] The following winter the manuscript grew to 63,000 words—Life only wanted 10,000 words—and he asked his friend A.E Hotchner for help organizing the manuscript.[105][106] Although Hemingway's mental deterioration was noticeable, he travelled to Spain to gather photographs for the manuscript. Alone in Spain, without Mary, Hemingway's mental state disintegrated rapidly. Life published the first installment in September 1960 to good reviews.[106] Hemingway left Spain, travelled straight to Idaho, and in November he entered the Mayo Clinic in Minnesota.[107] He was registered as George Saviers, the name of his physician from Sun Valley[107][108] He had been receiving treatment for high blood pressure and liver problems, and he may have believed he was going to be treated for hypertension.[109] Also, Hemingway suffered paranoia, believing he was being watched by the FBI. In fact, the FBI had opened a file on him during WWII when he used the Pilar to patrol the waters off Cuba, and J. Edgar Hoover had an agent in Havana watching Hemingway during the 1950s.[110] The FBI knew Hemingway was at the Mayo, as an agent documented in a letter written in January, 1961.[111] Hemingway suffered real problems as well: his eyesight was failing; his health was poor; and his home and possessions had been lost in Cuba (spring, 1961).[112]

In the spring of 1961, three months after his initial treatment at the Mayo with a series of ECT treatment, Hemingway attempted suicide. Mary convinced Saviers to an immediate hospitalization at the Sun Valley hospital, and from there he was returned to the Mayo for more shock treatments.[113] He was released in late June and arrived home in Ketchum on June 30. On the morning of July 2, 1961, he committed suicide by shooting himself with his shotgun.[114] Arriving at 7:40 a.m., Dr. Scott Earle certified the death.[115] Because foul play was ruled out an inquest was not required under Idaho state law.[116][117]

Other members of Hemingway's immediate family also committed suicide, including his father Clarence Hemingway; his sister Ursula; his brother Leicester; and his granddaughter Margaux Hemingway.[118] During his last years, Hemingway's behavior was similar to his father's before he committed suicide.[119] Hemingway's father may had the genetic disease haemochromatosis in which the inability to metabolize iron culminates in mental and physical deterioration.[120] Medical records, available in 1991, in fact confirm that Hemingway's haemochromatosis had been diagnosed early in 1961.[121] Additionally, Hemingway had been a heavy drinker for most of his life.[86]

Hemingway is interred in the town cemetery in Ketchum, Idaho, at the north end of town. A memorial was erected in 1966 at another location, overlooking Trail Creek, north of Ketchum. It is inscribed with a eulogy he wrote for a friend, Gene Van Guilder:

Best of all he loved the fall

The leaves yellow on the cottonwoods

Leaves floating on the trout streams

And above the hills

The high blue windless skies

Now he will be a part of them forever

Ernest Hemingway - Idaho - 1939

Notable works

During his Paris years, in addition to filing stories for the Toronto Star, Hemingway published short stories in various journals; the Parisian edition of the short story collection in our time (1924); the Three Stories and Ten Poems (1924);[122] and the revised and renamed American edition of In Our Time (1925).[123] Hemingway wrote the satire The Torrents of Spring in an effort to break his contract with his publisher Boni and Liveright. According to the contract Boni and Liveright were to publish Hemingway's next three books, one of which was to be a novel, with the proviso that if a newly submitted work were to be rejected the contract would be terminated.[124] Written in ten days, The Torrents of Spring was a satirical treatment of pretentious writers. Hemingway submitted the manuscript early in December 1925, and it was rejected by the end of the month. In January Max Perkins at Scribner's agreed to publish The Torrents of Spring in addition to Hemingway's future work.[125][126]

The Sun Also Rises (1926), was Hemingway's first novel. Written in 1925 and published in 1926, The Sun Also Rises (initially named Fiesta) was an autobiographical novel that epitomized the post-war expatriate generation for future generations.[127] In The Sun Also Rises, Hemingway melds Paris to Spain; vividly depicts the running of the bulls in Pamplona; presents the symmetry of bullfighting as a place to face death; and blends the frenzy of the fiesta with the tranquility of the Spanish landscape. The novel is generally considered Hemingway's best work.[128] The Sun Also Rises was adapted to film in 1957.[129]

Men Without Women (1927) was Hemingway's second collection of short stories. The volume consists of fourteen stories, ten of which had been previously published in magazines. The story subjects include bullfighting, infidelity, divorce and death. "The Killers", "Hills Like White Elephants" and "In Another Country" are considered to be among Hemingway's best work.[130]

Published in 1929, A Farewell to Arms, on the surface, is about the tragic romance between an American soldier Frederic Henry, and Catherine Barkley, a British nurse. The novel is about his World War I experiences and his relationship with Agnes von Kurowsky in Milan. Pauline underwent a ceasarean section as Hemingway was writing about Catherine Barkley's childbirth.[131] Below the surface, the novel is about World War I and individual tragedy within the larger picture of greater tragedy. The novel portrays the cynicism of soldiers, the displacement of populations. Hemingway's stature as an American writer was secured with the publication of A Farewell to Arms.[132] A Farewell to Arms was adapted to film in 1932 and again in 1957.[133][134]

Death in the Afternoon, a book about bullfighting, was published in 1932.[135] Hemingway became an aficionado of the sport after seeing the Pamplona fiesta in the 1920s, fictionalized in The Sun Also Rises.[136] In Death in the Afternoon, Hemingway explores the metaphysics of bullfighting—the ritualized, almost religious practice—that he considered analgous to the writer's search for meaning and the essence of life. In bullfighting, he found the elemental nature of life and death.[136] In his writings on Spain, he was influenced by the Spanish master Pío Baroja. When Hemingway won the Nobel Prize, he traveled to see Baroja, then on his death bed, specifically to tell him he thought Baroja deserved the prize more than he. Baroja agreed and something of the usual Hemingway tiff with another writer ensued despite his original good intentions.[95]

Green Hills of Africa (1935) initially appeared in serialization in Scribner's magazine, and was published in 1935.[137] An autobiographical journal of his 1933 trip to Africa, Hemingway presents the subject of big game hunting in a non-fiction form in Green Hills of Africa.[137]

To Have and Have Not (1937) is Hemingway's only novel set in the United States. Written sporadically between 1935 and 1937, and revised as he travelled back and forth from the Spanish Civil War, To Have and Have Not is a novel about Key West and Cuba. The novel also addresses social commentary of the 1930s, and received mixed critical reception.[138] To Have or Have Not was adapted to film in 1944, starring Humphrey Bogart and Lauren Bacall.[139]

The Fifth Column and the First Forty-Nine Stories was published in 1938, with Hemingway's only play The Fifth Column and 49 short stories. Hemingway's intention was, as he openly stated in his foreword, to write more.[citation needed] Many of the stories of the collection exist in other collections, including In Our Time, Men Without Women, Winner Take Nothing, and The Snows of Kilimanjaro. Some of the collection's important stories include "Old Man at the Bridge", "On The Quai at Smyrna", "Hills Like White Elephants", "One Reader Writes", "The Killers" and "A Clean, Well-Lighted Place". While these stories are rather short, the book also includes some longer stories, among them "The Snows of Kilimanjaro" and "The Short Happy Life of Francis Macomber".[140][141]

Hemingway wrote For Whom the Bell Tolls in Cuba, Key West, and Sun Valley, Idaho in 1939.[71] In Cuba, he lived in the Hotel Ambos-Mundos where he worked on the manuscript.[142][143] The novel was finished in July 1940, and published in October.[70][144] The novel is based on his experiences during the Spanish Civil War, with an American protagonist named Robert Jordan who fights with Spanish soldiers for the republicans.[145] The novel has three types of characters: those who are purely fictional; those based on real people but fictionalized; and those who were actual figures in the war. Set in Andalusia, in the town of Ronda, the action takes place during four days and three nights. For Whom the Bell Tolls became a Book-of-the-month choice, sold half a million copies within months, was nominated for a Pulitzer Prize, and became a literary triumph for Hemingway.[145] In 1944, the novel was adapted to film, starring Gary Cooper and Ingrid Bergman.[146]

Across the River and into the Trees (1950) is set in post-World War II Venice. Initially serialized in Cosmopolitan Magazine, the novel was criticized for being an unsuitable autobiography; and for presenting the protagonist, Cantwell, as a bitter soldier.[147] For the first time Hemingway received bad reviews for a novel, to which he responded in an interview with the New York Times: " 'Sure they can say anything about nothing happening in Across the River, all that happens is the defense of the lower Piave, the breakthrough in Normandy, the taking of Paris...plus a man who loves a girl and dies' ".[148] Generally the novel is considered better than the critical reviews he received upon publication.[149]

Written in 1951, and published in 1952, The Old Man and the Sea is the final work published during Hemingway's lifetime. The book was featured in Life Magazine on September 1, 1952, and five million copies of the magazine were sold in two days.[150] The Old Man and the Sea also became a Book-of-the Month selection, and made Hemingway a celebrity.[151] The novella received the Pulitzer Prize in May, 1952,[89] and was specifically cited when he was awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1954.[152][153] The success of The Old Man and the Sea made Hemingway an international celebrity.[151] The Old Man and the Sea is taught at schools around the world and continues to earn foreign royalties.[154]

Hemingway began The Garden of Eden in 1946 and wrote 800 pages.[155] The novel was published posthumously in a much-abridged form in 1986.[156] Early in 1950 he started work on a "sea trilogy", to consist of three sections: "The Sea When Young" (set in Bimini); "The Sea When Absent" (set in Havana); and "The Sea in Being". The latter was published in 1952 as The Old Man and the Sea.[157] He also wrote an unpublished "Sea-Chase" story which his wife and editor combined with the stories about the islands, renamed Islands in the Stream and published in 1970.[158]

Posthumous works

In 1956 Hemingway found a trunk left in the basement of the Ritz Hotel in Paris. The trunk contained notebooks he filled during the years he lived in Paris. He had the notebooks transcribed, and during the period he worked on A Dangerous Summer he finished the Paris manuscript also. Scribner's published A Moveable Feast in 1964 after Hemingway's death. A rewritten edition of the novel has been published in late 2009, with revisions made by Hemingway's grandson.[103] The restorations are based on a " 'typed manuscript with original notations in Hemingway's hand - the last draft of the book that he ever worked on' " and are apparently closer to the final version intended by Hemingway.[159]

Published in 1970, Islands in the Stream is largely autobiographical. Hemingway began work on the novel in 1946 and kept it in a bank vault during the last years of his life.[160] In a note forwarding Islands in the Stream, Mary Hemingway indicated that she worked with Charles Scribner, Jr. on "preparing this book for publication from Ernest's original manuscript." She also stated that "beyond the routine chores of correcting spelling and punctuation, we made some cuts in the manuscript, I feel that Ernest would surely have made them himself. The book is all Ernest's. We have added nothing to it." [citation needed] The novel is his seventh novel, and he conceived it as a trilogy about the sea, using the working title "The Sea Book".[161]

The Nick Adams Stories was published in 1972.[162] A full compilation of Hemingway's short stories was published as The Complete Short Stories Of Ernest Hemingway, in 1987.[163] As well, in 1969 The Fifth Column and Four Stories of the Spanish Civil War was published.[164] It contains Hemingway's only full length play, The Fifth Column, which was previously published along with the First Forty-Nine Stories in 1938, along with four unpublished works about Hemingway's experiences during the Spanish Civil War.[164]

Though not published until 1985, Hemingway worked on the draft of the The Dangerous Summer during 1959.[165] He finished the manuscript (which grew beyond the original scope) in the spring of 1960 and sent it to Life for serialization.[166] The first installment was published in September, 1960.[166] The initial project was to write about the matadors Ordonez and his brother-in-law Dominguin and their "mano a mano duel between two matadors".[165]

Hemingway began work on The Garden of Eden early in 1946, and had written eight hundred pages by the following summer.[155] For fifteen years he continued to work on the novel which remained uncompleted.[167] When published in 1986, the novel had 30 chapters and 70,000 words. The publisher's "note" admits that cuts were made to the novel, and according to biographers, Hemingway had achieved 48 chapters and 200,000 words. Scribner's removed a as much as two thirds of the extant manuscript and one long subplot.[167]

True at First Light was published in 1999. The book is a presented as a "fictional memoir" and was edited by Hemingway's second son, Patrick Hemingway. Six years later the work was republished a second time as Under Kilimanjaro.[159] The work is based on a partially written manuscript, and is about Hemingway's second trip to Africa. Under Kilimanjaro was edited by Robert W. Lewis and Robert E. Fleming who state: “this book deserves as complete and faithful a publication as possible without editorial distortion, speculation, or textually unsupported attempts at improvement.”[168]

Also published posthumously were several collections of his work as a journalist. These contain his columns and articles for Esquire Magazine, The North American Newspaper Alliance, and the Toronto Star; they include Byline: Ernest Hemingway edited by William White, and Hemingway: The Wild Years edited by Gene Z. Hanrahan. In 2006, a collection of miscellenea such as "statements, prefaces, blurbs", written by Hemingway was edited by Matthew J. Bruccoli.[169]

Hemingway was a prolific correspondent and, in 1981, many of his letters were published by Scribner's in Ernest Hemingway Selected Letters edited by Carlos Baker. Although Hemingway wrote to his executors in 1958 asking that his letters not be published, Mary Hemingway made the decision to publish the letters in 1979.[170] Further letters were published in a book of his correspondence with his editor Max Perkins, The Only Thing that Counts in 1996.[126]

Writing style

The New York Times wrote in 1926 of Hemingway's first novel: "No amount of analysis can convey the quality of The Sun Also Rises. It is a truly gripping story, told in a lean, hard, athletic narrative prose that puts more literary English to shame".[171] The Sun Also Rises is written in the spare, tightly written prose for which Hemingway is famous, a style which has influenced countless crime and pulp fiction novels.[172] It is a style which some critics consider Hemingway's greatest contribution to literature.[173] But the simplicity is deceptive. Hemingway uses polysyndeton to convey both a timeless immediacy and a Biblical grandeur. Hemingway's polysyndetonic sentence—or, in later works, his use of subordinate clauses[174]—uses conjunctions to juxtapose startling visions and images; the critic Jackson Benson has compared them to haikus.[175] Many of Hemingway's acolytes misinterpreted his lead and frowned upon all expression of emotion; Saul Bellow satirized this style as "Do you have emotions? Strangle them."[176] However, Hemingway intent was not to eliminate emotion but to portray it more scientifically. Hemingway thought it would be easy, and pointless, to describe emotions; he sculpted his bright and finely chiseled collages of images in order to grasp "the real thing, the sequence of motion and fact which made the emotion and which would be as valid in a year or in ten years or, with luck and if you stated it purely enough, always".[177] This use of an image as an objective correlative is characteristic of Ezra Pound, T.S. Eliot, James Joyce, and of course Proust[178] compares Hemingway's and Proust's use of memory to find the objective correlative. Hemingway's letters refer to Proust's Remembrance of Things Past several times over the years, and indicate he might have read the massive book at least twice.[179] and is also part of the Japanese poetic canon.[180] Hemingway's writing style, in other words, is not artless but poetic.

Influence and legacy

The influence of Hemingway's writings on American literature was considerable and continues today. James Joyce called "A Clean, Well Lighted Place" "one of the best stories ever written". (The same story also influenced several of Edward Hopper's best known paintings, most notably "Nighthawks."[181] ) Pulp fiction and "hard boiled" crime fiction (which flourished from the 1920s to the 1950s) often owed a strong debt to Hemingway.[citation needed] During World War II, J. D. Salinger met and corresponded with Hemingway, whom he acknowledged as an influence.[182] In one letter to Hemingway, Salinger wrote that their talks "had given him his only hopeful minutes of the entire war," and jokingly "named himself national chairman of the Hemingway Fan Clubs."[183] Hunter S. Thompson often compared himself to Hemingway, and terse Hemingway-esque sentences can be found in his early novel, The Rum Diary.[citation needed] Hemingway's terse prose style--"Nick stood up. He was all right."-- is known to have inspired Charles Bukowski, Chuck Palahniuk, Douglas Coupland and many Generation X writers. Hemingway's style also influenced Jack Kerouac and other Beat Generation writers. Hemingway also provided a role model to fellow author and hunter Robert Ruark, who is frequently referred to as "the poor man's Ernest Hemingway."[citation needed] Popular novelist Elmore Leonard, who has authored scores of western- and crime-genre novels, cites Hemingway as his preeminent influence, and this is evident in his tightly written prose. Though Leonard has never claimed to write serious literature, he has said: "I learned by imitating Hemingway.... until I realized that I didn't share his attitude about life. I didn't take myself or anything as seriously as he did."[citation needed]

Family

- Parents

- Father: Clarence Hemingway. Born September 2, 1871, died December 6, 1928. General practitioner and obstetrician.[184]

- Mother: Grace Hall Hemingway. Born June 15, 1872, died June 28, 1951

- Siblings

- Marcelline Hemingway. Born January 15, 1898, died December 9, 1963

- Ursula Hemingway. Born April 29, 1902, died October 30, 1966

- Madelaine Hemingway. Born November 28, 1904, died January 14, 1995

- Carol Hemingway. Born July 19, 1911, died October 27, 2002

- Leicester Hemingway. Born April 1, 1915, died September 13, 1982

- Own families

- Elizabeth Hadley Richardson. Married September 3, 1921, divorced April 4, 1927, died January 22, 1979.

- Son, John Hadley Nicanor "Jack" Hemingway (aka Bumby). Born October 10, 1923, died December 1, 2000.

- Granddaughter, Joan (Muffet) Hemingway

- Granddaughter, Margaux Hemingway. Born February 16, 1954, died July 2, 1996

- Granddaughter, Mariel Hemingway. Born November 22, 1961

- Great-Granddaughter, Dree Hemingway. Born 1987

- Pauline Pfeiffer. Married May 10, 1927, divorced November 4, 1940, died October 21, 1951.

- Son, Patrick. Born June 28, 1928.

- Granddaughter, Mina Hemingway

- Son, Gregory Hemingway (called 'Gig' by Hemingway; later called himself 'Gloria'). Born November 12, 1931, died October 1, 2001.

- Grandchildren, Patrick, Edward, Sean, Brendan, Vanessa, Maria, Adiel, John Hemingway and Lorian Hemingway

- Martha Gellhorn. Married November 21, 1940, divorced December 21, 1945, died February 15, 1998.

- Mary Welsh. Married March 14, 1946, died November 26, 1986.

Tributes and honors

- Honors

During his lifetime Hemingway was awarded:[citation needed]

- American Academy of Arts and Letters Award of Merit, 1954;

- two medals for bull-fighting.

Tributes

- A minor planet, discovered in 1978 by Soviet astronomer Nikolai Stepanovich Chernykh, was named for him—3656 Hemingway.[185]

- On July 17, 1989, the United States Postal Service issued a 25-cent postage stamp honoring Hemingway.[186]

- Hemingway is the implied subject of the Ray Bradbury story The Kilimanjaro Device. Using the plot device of a time machine, the tale creates a loving tribute that undoes his suicide. The story appears in the Bradbury collection I Sing The Body Electric.

- In 1999, Michael Palin retraced the footsteps of Hemingway, in Michael Palin's Hemingway Adventure, a BBC television documentary, one hundred years after the birth of his favorite writer. The journey took him through many sites including Chicago, Paris, Italy, Africa, Key West, Cuba, and Idaho. Together with photographer Basil Pao, Palin also created a book version of the trip. The text of the book is available for free on Palin's website. Four years earlier, Palin also wrote a book, Hemingway's Chair, about an assistant post-office manager obsessed with Hemingway.

- Since 1987, actor-writer Ed Metzger has portrayed the life of Ernest Hemingway in his one-man stage show, Hemingway: On The Edge, featuring stories and anecdotes from Hemingway's own life and adventures. Metzger quotes Hemingway, "My father told me never kill anything you're not going to eat. At the age of 9, I shot a porcupine. It was the toughest lesson I ever had." More information about the show is available at his website

- Hemingway's World War II experiences in Cuba have been novelized by Dan Simmons as a spy thriller, The Crook Factory.

- Hemingway, played by Jay Underwood, was a recurring character in The Young Indiana Jones Chronicles. In one episode, set in Northern Italy in 1916, Hemingway the ambulance driver gives young Indy (Sean Patrick Flanery) advice about women—only to discover that he and Indy are rivals for the heart of the same woman. (The episode shows Indy unwittingly influencing Hemingway's future writing, by reciting the Elizabethan poem, A Farewell to Arms by George Peele.) In another episode, set in Chicago in 1920, Hemingway the newspaper reporter helps Indy and a young Eliot Ness in their investigation of the murder of gangster James Colosimo.

- The 1993 motion picture Wrestling Ernest Hemingway, about the friendship of two retired men, one Irish, one Cuban, in a seaside town in Florida, starred Robert Duvall, Richard Harris, Shirley MacLaine, Sandra Bullock, and Piper Laurie.

- The 1996 motion picture In Love and War, based on the book Hemingway in Love and War by Henry S. Villard and James Nagel, is the story of the young reporter Ernest Hemingway (played by Chris O'Donnell) as an ambulance driver in Italy during World War I. While bravely risking his life in the line of duty, he is injured and ends up in the hospital, where he falls in love with his nurse, Agnes von Kurowsky (Sandra Bullock).

- In the 1989 James Bond film Licence to Kill, Bond (played by Timothy Dalton) meets with M at the Hemingway House. When asked for his gun after handing in his resignation, Bond exclaims "I guess it's a Farewell To Arms," in reference to the work of the same name.

- Joyce Carol Oates wrote a loosely biographical short story of the last days of Hemingway called Papa at Ketchum, 1961 in her 2008 book Wild Nights.

- Ska/Punk band Streetlight Manifesto references Hemingway in their 2003 song "Here's to LIfe". The song discusses Streetlight Manifesto's lead singer Tomas Kalnoky heroes which include Hemingway. "Hemingway never seemed to mind the banalities of a normal life and I find, it gets harder every time So he aimed the shotgun into the blue Placed his face in between the twoand sighed, "Here's To Life!"

- Every year for the past thirty years the International Imitation Hemingway Competition, also knowing as the "Bad Hemingway," has held a competition for the best worst story written in the style of Ernest Hemingway.[187]

Footnotes

- ^ a b c d e f g ResourceCenter

- ^ Meyers 1985, p. 8

- ^ Meyers 1985, p. 3

- ^ a b Meyers 1985, p. 13

- ^ Meyers 1985, p. 17

- ^ Meyers 1985, p. 19

- ^ ""Lardner Connections"". Retrieved 2007-03-22.

- ^ Meyers 1985, p. 23

- ^ "Star style and rules for writing". The Kansas City Star. KansasCity.com. Retrieved 2009–08–29.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ Meyers 1985, p. 47

- ^ Meyers 1985, p. 27

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Putnam

- ^ Meyers 1985, p. 30

- ^ Meyers 1985, p. 31

- ^ Desnoyers, p. 3

- ^ Meyers 1985, p. 37

- ^ Meyers 1985, p. 40

- ^ Meyers 1985, p. 41

- ^ a b Meyers 1985, pp. 51–53

- ^ Meyers 1985, p. 56

- ^ Meyers 1985, p. 58

- ^ Meyers 1985, pp. 60–62

- ^ Meyers 1985, p. 61

- ^ Mellow 1992, p. 308

- ^ Meyers 1985, pp. 77–81

- ^ Meyers 1985, pp. 73–74

- ^ Meyers 1985, p. 82

- ^ a b Desnoyers, p. 5

- ^ Meyers 1985, pp. 69–70

- ^ Meyers 1985, p. 123

- ^ Desnoyers, p. 4

- ^ Meyers 1985, p. 126

- ^ Meyers 1985, p. 127

- ^ Meyers 1985, pp. 159–160

- ^ Meyers 1985, p. 119

- ^ Meyers 1985, p. 189

- ^ Meyers 1985, p. 172

- ^ Desnoyers, p. 8

- ^ Meyers 1985, p. 174

- ^ Meyers 1985, pp. 184–185

- ^ Meyers 1985, p. 195

- ^ Meyers 1985, p. 204

- ^ a b Meyers 1985, p. 208

- ^ Meyers 1985, p. 2

- ^ Meyers 1985, p. 215

- ^ Meyers 1985, p. 222

- ^ Meyers 1985, p. 224

- ^ Meyers 1985, p. 226

- ^ Meyers 1985, p. 227

- ^ Mellow 1985, p. 402

- ^ a b Desnoyers, p. 9

- ^ Independent

- ^ Meyers 1985, pp. 261–264

- ^ Meyers 1985, p. 280

- ^ Meyers 1985, p. 292

- ^ Mellow 1992, p. 488

- ^ Koch 2005, p. 87

- ^ Meyers 1985, p. 311

- ^ Koch 2005, p. 164

- ^ Meyers 1985, pp. 308–309

- ^ Meyers 1985, p. 298

- ^ Meyers 1985, pp. 316–317

- ^ Koch 2005, p. 134

- ^ Thomas 2001, p. 385

- ^ Meyers 1985, p. 321

- ^ Thomas 2001, p. 833

- ^ Matthew J. Bruccoli (2005). "Hemingway and the Mechanism of Fame". pp. 98-100

- ^ Desnoyers, p. 11

- ^ Desnoyers, p. 10

- ^ a b Meyers 1985, p. 334

- ^ a b Meyers 1985, p. 326

- ^ Meyers 1985, p. 342

- ^ Meyers 1985, p. 356

- ^ Meyers 1985, p. 361

- ^ Meyers 1985, p. 398

- ^ Meyers 1985, p. 400

- ^ Meyers 1985, p. 405

- ^ Meyers 1985, p. 408

- ^ Mellow 1992, p. 535

- ^ Mellow 1992, p. 541

- ^ Meyers 1985, p. 411

- ^ Meyers 1985, p. 394

- ^ Meyers 1985, p. 416

- ^ a b c Meyers 1985, pp. 420–421

- ^ Mellow 1992, pp. 548–550

- ^ a b c Desnoyers, p. 12

- ^ a b Meyers 1985, p. 440

- ^ Meyers 1985, p. 465

- ^ a b Meyers 1985, p. 489

- ^ Meyers 1985, pp. 505–506

- ^ Meyers 1985, p. 507

- ^ a b c Baker 1972, p. 5338

- ^ Meyers 1985, p. 509

- ^ "Ernest Hemingway The Nobel Prize in Literature 1954 Banquet Speech". The Nobel Foundation. Retrieved 2009-12-10.

- ^ a b Meyers 1985, p. 512

- ^ Mellow 1992, p. 594

- ^ a b Mellow 1992, p. 595

- ^ Meyers 1985, pp. 516–519

- ^ Gonzalez Echevarria, Roberto (1980). "The Dictatorship of Rhetoric/the Rhetoric of Dictatorship: Carpentier, Garcia Marquez, and Roa Bastos". Latin American Research Review. 15 (3): 205–228.

For example, the assassination of Manolo Castro is retold by alluding to Hemingway's "The Shot,…"

- ^ "Restauracion Museo Hemingway (Official website) - Finca Vigía" (in Spanish). Consejo Nacional de Patrimonio Cultural- Cuba. 2009. Retrieved 2009-01-06.

- ^ a b Mellow 1992, p. 599

- ^ Meyers 1985, p. 533

- ^ a b Hotchner, A.E. (2009–07–19). "Don't Touch 'A Movable Feast'". The New York Times. Retrieved 2009–09–3.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=and|date=(help); Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ Meyers 1985, p. 520

- ^ Meyers 1985, p. 542

- ^ a b Mellow 1992, pp. 598–600

- ^ a b Mellow 1992, p. 601

- ^ Meyers 1985, p. 546

- ^ Meyers 1985, p. 545

- ^ Mellow 1992, pp. 597–598

- ^ Meyers 1985, p. 543

- ^ Meyers 1985, p. 544

- ^ Meyers 1985, p. 551

- ^ Meyers 1985, p. 560

- ^ Baker, Carlos (1969). Ernest Hemingway: A Life Story. New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons. p. 668. ISBN 0-684-14740-8.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ Meyers 1985, p. 561

- ^ "Hemingway Inquest Is Ruled Out After Authorities Talk to Family". New York Times. 1961–7–4. Retrieved 2009–12–13.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=and|date=(help) - ^ "Leicester Hemingway". Harry Ransom Center University of Texas at Austin. Retrieved 2009-12-12.

- ^ Burwell 1996, p. 234

- ^ Burwell 1996, p. 14

- ^ Burwell 1996, p. 189

- ^ Mellow 1992, p. 252

- ^ Mellow 1992, p. 314

- ^ Mellow 1992, p. 317

- ^ Mellow 1992, p. 321

- ^ a b Matthew J. Bruccoli (1996, November 19). "The Only Thing that Counts". New York Times. Retrieved 2009–12–13.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=and|date=(help) - ^ Mellow 1992, p. 302

- ^ Meyers 1985, p. 192

- ^ "The Sun Also Rises (1957)". film. Internet Movie Database. Retrieved October 8, 2009.

- ^ Meyers 1985, pp. 195–196

- ^ Meyers 1985, pp. 216–217

- ^ Mellow 1992, p. 378

- ^ "A Farewell to Arms (1932)". film. Internet Movie Database. Retrieved October 8, 2009.

- ^ "A Farewell to Arms (1957)". film. Internet Movie Database. Retrieved October 8, 2009.

- ^ Mellow 1992, p. 415

- ^ a b Meyers 1985, pp. 118–119

- ^ a b Meyers 1985, p. 266

- ^ Meyers 1985, pp. 292–296

- ^ "To Have or Have Not". film. Internet Movie Database. Retrieved October 8, 2009.

- ^ Mellow 1992, p. 472

- ^ Mellow 1992, p. 514

- ^ Mellow 1992, p. 516

- ^ One source, however, says he began the book at the Sevilla Biltmore Hotel and finished it at "Finca Vigia"

- ^ Meyers 1985, p. 339

- ^ a b Meyers 1985, pp. 335–338

- ^ "For Whom the Bell Tolls (1944)". film. Internet Movie Database. Retrieved October 8, 2009.

- ^ Mellow 1992, pp. 459–451

- ^ Mellow 1992, p. 561

- ^ Meyers 1985, p. 470

- ^ "A Hemingway timeline Any man's life, told truly, is a novel". The Kansas City Star. KansasCity.com. 06/27/99. Retrieved 2009–08–29.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=and|date=(help) - ^ a b Desnoyers, p. 13

- ^ "Heroes:Life with Papa". Time. 1954. Retrieved 2009–12–12.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ "The Nobel Prize in Literature 1954". Nobelprize.org. Retrieved 2009-10-04.

- ^ Meyers 1985, p. 485

- ^ a b Meyers 1985, p. 436 Cite error: The named reference "Meyers p436" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ McDowell, Edwin (December 17, 1985). "New Hemingway Novel To Be Published in May". New York Times.

- ^ Baker 1972, pp. 381–382

- ^ Baker 1972, p. 384

- ^ a b Churchill, Sarah (24 October 2009). "The Final Cut". The Guardian.

- ^ Meyers 1985, pp. 483–484

- ^ Baker 1972, p. 379

- ^ NYTNickAdams

- ^ Hemingway, Ernest (1987). The Complete Short Stories of Ernest Hemingway: The Finca Vigia Edition. New York: Scribner. ISBN 0-684-843342-3. Retrieved 2010-1-15.

{{cite book}}: Check|isbn=value: length (help); Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ a b Beegel, Susan (1989). Hemingway's Neglected Short Fiction: New Perspectives. University of Alabama Press. p. 11. ISBN 0-8173-0586-6. Retrieved 2009-10-24.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) Cite error: The named reference "Beegel" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page). - ^ a b Kakutani, Michiko (June 1, 1985). "Books of The Times; Hemingway at Sunset". New York Times.

- ^ a b Baker 1972, pp. 342–343

- ^ a b Doctorow, E.L (May 18, 1986). "Braver Than We Thought". The New York Times.

- ^ "An American Literary Treasure". Kent State University Press. Retrieved 2009-10-22.

- ^ Bruccoli, Matthew (ed.). Hemingway and the Mechanism of Fame. Judith S. Baughman.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|month=(help) - ^ Baker, Carlos, ed. (1981). Ernest Hemingway Selected Letters 1917 -1961. New York: Charles Scribner's. p. xxiii. ISBN 0-684-16765-4.

- ^ "Marital Tragedy". The New York Times. The New York Times. October 31, 1926. Retrieved 2010-01-15.

- ^ Donaldson, The Cambridge Companion to Hemingway, p.87

- ^ R. B. Shuman, Great American Writers, p.659

- ^ McCormick, p. 49

- ^ J. Benson, The Short Stories of Ernest Hemingway, p 309

- ^ A.Hoberik, Twilight of the Middle Class, p.87

- ^ Hemingway, Death in the Afternoon, chapter 1

- ^ McCormick, p. 47

- ^ Burwell 1996, p. 187

- ^ R. Starrs, An Artless Art, p. 77

- ^ Wells, Walter, Silent Theater: The Art of Edward Hopper, London/New York: Phaidon, 2007

- ^ Lamb, Robert Paul (Winter 1996). "Hemingway and the creation of twentieth-century dialogue - American author Ernest Hemingway" (reprint). Twentieth Century Literature. Retrieved 2007-07-10.

- ^ Baker, Carlos (1969). Ernest Hemingway: A Life Story. New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons. pp. 420, 646. ISBN 0-02-001690-5.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ Stewart, Matthew (2001). Modernism and Tradition in Ernest Hemingway's "In our Time": A Guide for Students and Readers. Boydell & Brewer. ISBN 1-57113-017-9, 9781571130174.

{{cite book}}: Check|isbn=value: invalid character (help) - ^ Schmadel, Lutz D. (2003). Dictionary of Minor Planet Names (5th ed.). New York: Springer Verlag. p. 307. ISBN 3-540-00238-3.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ Scott catalog # 2418.

- ^ International Imitation Hemingway Competition article

References

- Baker, Carlos (1969). Ernest Hemingway: A Life Story. New York: Scribner’s. ISBN 0-02-001690-5.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - Baker, Carlos (1972). Hemingway: The Writer as Artist (4th ed.). Princeton University Press. ISBN 0-691-01305-5.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|note=ignored (help)CS1 maint: ref duplicates default (link) - Baker, Carlos, ed. (1981). Ernest Hemingway Selected Letters 1917 -1961. New York: Scribner's. ISBN 0-684-16765-4.

- Burwell, Rose Marie. Hemingway: the postwar years and the posthumous novels. New York: Cambridge University Press. p. 189. ISBN 0–521–48199–6. Retrieved 2009–12–11.

{{cite book}}: Check|isbn=value: invalid character (help); Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - Desnoyers, Megan Floyd. "Ernest Hemingway: A Storyteller's Legacy". John F. Kennedy Presidential Library Online Resources. John F. Kennedy Presidential Library and Museum. Retrieved 2009-12-08.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: ref duplicates default (link) - "Ernest Hemingway Biography: Childhood". The Hemingway Resource Center. Retrieved 2009–08–29.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - Hallengren, Anders (28 August 2001). "A Case of Identity: Ernest Hemingway". Nobelprize.org. Retrieved 2009-10-22.

- Koch, Stephen (2005). The Breaking Point: Hemingway, Dos Passos, and the Murder of Jose Robles. New York: Counterpoint. pp. 87–164. ISBN 1-58243-280-5. Retrieved 2009-9-18.

{{cite book}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help)CS1 maint: ref duplicates default (link) - McCormick, John. American Literature 1919–1932. London: Routledge and Keegan Paul. Retrieved 2009–12–13.

{{cite book}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help)CS1 maint: ref duplicates default (link) - Meyers, Jeffrey (1985). Hemingway: A Biography. London: Macmillan. ISBN 0-333-42126-4.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: ref duplicates default (link) - Mellow, James R. (1992). Hemingway: A Life Without Consequences. New York: Houghton Mifflin. ISBN 0-395-37777-3.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: ref duplicates default (link) - Lingeman, Richard (April 25, 1972). "More Posthumous Hemingway". The New York Times. Retrieved 2009-10-22.

- Ondaatje, Christopher (30 October 2001). "Bewitched by Africa's strange beauty". The Independent. independent.co.uk. Retrieved 2009–09–16.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - Putnam, Thomas (2006). "Hemingway on War and Its Aftermath". The National Archives. Retrieved 2008-05-05.

- Thomas, Hugh (2001). The Spanish Civil War. New York: Modern Library. ISBN 0-375-75515-2. Retrieved 2009-9-18.

{{cite book}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help)CS1 maint: ref duplicates default (link)

Further reading

- Baker, Carlos (1962). Ernest Hemingway: Critiques of Four Major Novels. A Scribner research anthology. Scribner. ISBN 0-684-41157-1.

- Brian, Denis (1987). The True Gen: An Intimate Portrait of Hemingway by Those Who Knew Him. Grove Press. ISBN 0-8021-0006-6.

- Bruccoli, Matthew Joseph (1978). Scott and Ernest: The Authority of Failure and the Authority of Success. Bodley Head. ISBN 0-370-30140-4.

- Burgess, Anthony (1978). Ernest Hemingway. Literary lives. London: Thames and Hudson (published 1986). ISBN 0-500-26017-6.

- Cappel, Constance (1966). Hemingway in Michigan. Vermont Crossroads Press (published 1977). ISBN 0-915248-13-1.

- Hemingway, Ernest (1944). Cowley, Malcolm (ed.). Hemingway (The Viking Portable Library). Viking Press. OCLC 505504.

- Lynn, Kenneth Schuyler (1987). Hemingway. Simon and Schuster. ISBN 0-671-49872-X.

- Lynn, Steve (1994). Texts and Contexts: Writing About Literature with Critical Theory. HarperCollins. p. 5–7. ISBN 0-06-500099-4.

- Montes, Jorge García; Ávila, Antonio Alonso (1970). Historia del Partido Comunista en Cuba. Ediciones Universal. p. 362. OCLC 396804.

- Reynolds, Michael S. (1986). The Young Hemingway. Basil Blackwell. ISBN 0-631-14786-1.

- Wagner-Martin, Linda (2000). A Historical Guide to Ernest Hemingway. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-512151-1.

- Stewart, Matthew (2001). Modernism and Tradition in Ernest Hemingway's "In our Time": A Guide for Students and Readers. Boydell & Brewer. ISBN 1-57113-017-9, 9781571130174.

{{cite book}}: Check|isbn=value: invalid character (help) - Young, Philip (1952). Ernest Hemingway. New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston. OCLC 237958.

External links

- Ernest Hemingway.org.uk

- Timeless Hemingway

- The Charles D. Field Collection of Ernest Hemingway(call number M0440; 1.25 linear ft) are housed in the Department of Special Collections and University Archives at Stanford University Libraries

- The Hemingway Society

- New York Times obituary, July 3, 1961

- Michael Palin's Hemingway Adventure Based on a PBS lecture series narrated by Michael Palin.

- CNN: A Hemingway Retrospective

- Ernest Hemingway Home and Museum in Key West, Florida, official website

- The Hemingway-Pfeiffer Museum and Educational Center

- Hemingway’s Reading 1910–1940

- Template:Worldcat id

- Hemingway's work on IBList

- Ernest Hemingway's Collection at The University of Texas at Austin

See also

- 1899 births

- 1961 deaths

- American essayists

- American expatriates in Canada

- American expatriates in Cuba

- American expatriates in France

- American expatriates in Italy

- American expatriates in Spain

- American hunters

- American journalists

- American Nobel laureates

- American memoirists

- American military personnel of World War I

- American novelists

- American people of the Spanish Civil War

- American short story writers

- American socialists

- Anti-fascists

- English Americans

- Ernest Hemingway

- History of Key West, Florida

- Nobel laureates in Literature

- Operation Overlord people

- People from Oak Park, Illinois

- Pulitzer Prize for Fiction winners

- Recipients of the Silver Medal of Military Valor

- Suicides by firearm in Idaho

- War correspondents

- Writers from Chicago, Illinois

- Writers who committed suicide

- Writers who served in the military