Mujaddid: Difference between revisions

Pepperbeast (talk | contribs) Undid revision 1133121297 by Jssyedmadar (talk) stop doing this, and discuss on the article talk page. |

Jssyedmadar (talk | contribs) Undid revision 1133188045 by Pepperbeast (talk) This would be ongoing until you respond to the valid objections being brought with references and citations. Note that the entry of Mirza Ghulam Ahmad is retained in the original page, but this claim is not accepted by more than 90% of Muslims. |

||

| Line 34: | Line 34: | ||

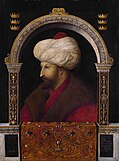

[[File:تخطيط كلمة ابن تيمية.png|thumb|[[Ibn Taymiyyah]] (1263–1328), mujaddid of the 7th century, is known for his theological, political and military activities.]] |

[[File:تخطيط كلمة ابن تيمية.png|thumb|[[Ibn Taymiyyah]] (1263–1328), mujaddid of the 7th century, is known for his theological, political and military activities.]] |

||

While there is no formal mechanism for designating a ''mujaddid'' in [[Sunni Islam]], there is often a popular consensus. The [[Shia]] and [[Ahmadiyya]]<ref name="Ghulam">{{cite book|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=-RfYBgAAQBAJ|title=Religion in Southeast Asia: An Encyclopedia of Faiths and Cultures|date=10 March 2015|publisher=[[ABC-CLIO|ABC-CLIO, LLC]]|isbn=9781610692502}}</ref>{{Page needed|date=September 2018}}<ref name=" |

While there is no formal mechanism for designating a ''mujaddid'' in [[Sunni Islam]], there is often a popular consensus. The [[Shia]] and [[Ahmadiyya]]<ref name="Ghulam">{{cite book|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=-RfYBgAAQBAJ|title=Religion in Southeast Asia: An Encyclopedia of Faiths and Cultures|date=10 March 2015|publisher=[[ABC-CLIO|ABC-CLIO, LLC]]|isbn=9781610692502}}</ref>{{Page needed|date=September 2018}}<ref name="Jesudas M. Athyal 2015 p 1">Jesudas M. Athyal, Religion in Southeast Asia: An Encyclopedia of Faiths and Cultures, (ABC-CLIO, LLC 2015), p 1. {{ISBN|9781610692496}}.</ref> have their own list of mujaddids.<ref name="MICE"/> |

||

===First century (after the prophetic period) (August 3, 718)=== |

===First century (after the prophetic period) (August 3, 718)=== |

||

| Line 107: | Line 107: | ||

===Fourteenth century (November 21, 1979)=== |

===Fourteenth century (November 21, 1979)=== |

||

* [[Ashraf Ali Thanwi]] (1863–1943)<ref>{{Cite journal|last=Mian|first=Ali Altaf|date=2015|title=Surviving Modernity: Ashraf 'Ali Thanvi (1863–1943) and the Making of Muslim Orthodoxy in Colonial India|url=https://dukespace.lib.duke.edu/dspace/handle/10161/9815|journal=Duke University|language=en}}</ref> |

* [[Ashraf Ali Thanwi]] (1863–1943)<ref>{{Cite journal|last=Mian|first=Ali Altaf|date=2015|title=Surviving Modernity: Ashraf 'Ali Thanvi (1863–1943) and the Making of Muslim Orthodoxy in Colonial India|url=https://dukespace.lib.duke.edu/dspace/handle/10161/9815|journal=Duke University|language=en}}</ref> |

||

| ⚫ | *[[Mirza Ghulam Ahmad]] (1835–1908)<ref>Adil Hussain Khan, [https://books.google.com/books?id=C2DxBwAAQBAJ ''From Sufism to Ahmadiyya: A Muslim Minority Movement in South Asia''], Indiana University Press, 6 April 2015, p. 42.</ref><ref>{{cite book | title=Prophecy Continuous: Aspects of Ahmadi Religious Thought and Its Medieval Background | author=Friedmann, Yohanan | year=2003 | publisher=Oxford University Press | page=107 | isbn=965-264-014-X}}</ref>{{refn|Mirza Ghulam Ahmad is the founder of the [[Ahmadiyya]] sect. The [[Sunni Islam|Sunni]]-Shia mainstream and the majority of Muslims reject the Ahmadiyya sect as it believes in non-law bearing prophethood after Muhammad.}}<ref>{{Cite web|url=http://www.oxfordislamicstudies.com/article/opr/t125/e85|title=Ahmadis - Oxford Islamic Studies Online|website=www.oxfordislamicstudies.com|language=en|access-date=2018-09-03|quote=Controversial messianic movement founded by Mirza Ghulam Ahmad in Qadian, Punjab (British-controlled India), in 1889. Founder claimed to be a “nonlegislating” prophet (thus not in opposition to the mainstream belief in the finality of Muhammad's “legislative” prophecy) with a divine mandate for the revival and renewal of Islam.}}</ref> |

||

* [[Said Nursî]] (1878–1960)<ref name="Muslims: Their Religious Beliefs and Practices">{{cite book |last=Rippin|first=Andrew|title=Muslims: Their Religious Beliefs and Practices|year= |publisher= |page=282|isbn= }}</ref> |

* [[Said Nursî]] (1878–1960)<ref name="Muslims: Their Religious Beliefs and Practices">{{cite book |last=Rippin|first=Andrew|title=Muslims: Their Religious Beliefs and Practices|year= |publisher= |page=282|isbn= }}</ref> |

||

* [[Abdul-Rahman al-Sa'di]] (1889-1957)<ref>{{Cite journal|last=Smith|first=Van Mitchell|date=September 1974|title=History of West Africa, Vol. 2|url=http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/03612759.1974.9946605|journal=History: Reviews of New Books|volume=2|issue=10|pages=251|doi=10.1080/03612759.1974.9946605|issn=0361-2759}}</ref> |

* [[Abdul-Rahman al-Sa'di]] (1889-1957)<ref>{{Cite journal|last=Smith|first=Van Mitchell|date=September 1974|title=History of West Africa, Vol. 2|url=http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/03612759.1974.9946605|journal=History: Reviews of New Books|volume=2|issue=10|pages=251|doi=10.1080/03612759.1974.9946605|issn=0361-2759}}</ref> |

||

| Line 113: | Line 112: | ||

* [[Murabit al-Hajj]] (1913 - 2018) <ref name="Sufism in West Africa">{{cite journal|author=Rüdiger Seesemann|title=Sufism in West Africa|journal=Religion Compass |url=https://compass.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/j.1749-8171.2010.00241.x|year=2010|volume=4 |issue=10 |publisher=Blackwell Publishing Ltd|pages= 606–614|doi=10.1111/j.1749-8171.2010.00241.x }}</ref> |

* [[Murabit al-Hajj]] (1913 - 2018) <ref name="Sufism in West Africa">{{cite journal|author=Rüdiger Seesemann|title=Sufism in West Africa|journal=Religion Compass |url=https://compass.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/j.1749-8171.2010.00241.x|year=2010|volume=4 |issue=10 |publisher=Blackwell Publishing Ltd|pages= 606–614|doi=10.1111/j.1749-8171.2010.00241.x }}</ref> |

||

* [[Muhammad 'Alawi al-Maliki]] (1944-2004) <ref>{{Cite news|date=2015-03-02|title=next mujaddid- Syekh Muhammad Alawi al-Maliki, Benteng Sunni Abad ke-21|url=https://republika.co.id/berita/koran/news-update/15/03/02/nkkosb53-next-mujaddid-syekh-muhammad-alawi-almaliki-benteng-sunni-abad-ke21|access-date=2020-06-08|work=[[Republika (Indonesian newspaper)]] |language=id}}</ref><ref>{{Cite web|last=Jalali|title=Correct Understanding of the Mawlid – 1 {{!}} TAQWA.sg {{!}} Tariqatu-l Arusiyyatu-l Qadiriyyah Worldwide Association (Singapore) - Shari'a, Tariqa, Ma'rifa, and Haqiqa|url=http://taqwa.sg/v/articles/correct-understanding-of-the-mawlid-1/|access-date=2020-06-08|language=en-GB}}</ref> |

* [[Muhammad 'Alawi al-Maliki]] (1944-2004) <ref>{{Cite news|date=2015-03-02|title=next mujaddid- Syekh Muhammad Alawi al-Maliki, Benteng Sunni Abad ke-21|url=https://republika.co.id/berita/koran/news-update/15/03/02/nkkosb53-next-mujaddid-syekh-muhammad-alawi-almaliki-benteng-sunni-abad-ke21|access-date=2020-06-08|work=[[Republika (Indonesian newspaper)]] |language=id}}</ref><ref>{{Cite web|last=Jalali|title=Correct Understanding of the Mawlid – 1 {{!}} TAQWA.sg {{!}} Tariqatu-l Arusiyyatu-l Qadiriyyah Worldwide Association (Singapore) - Shari'a, Tariqa, Ma'rifa, and Haqiqa|url=http://taqwa.sg/v/articles/correct-understanding-of-the-mawlid-1/|access-date=2020-06-08|language=en-GB}}</ref> |

||

==Claimants in other traditions== |

|||

| ⚫ | *[[Mirza Ghulam Ahmad]] (1835–1908)<ref>Adil Hussain Khan, [https://books.google.com/books?id=C2DxBwAAQBAJ ''From Sufism to Ahmadiyya: A Muslim Minority Movement in South Asia''], Indiana University Press, 6 April 2015, p. 42.</ref><ref>{{cite book | title=Prophecy Continuous: Aspects of Ahmadi Religious Thought and Its Medieval Background | author=Friedmann, Yohanan | year=2003 | publisher=Oxford University Press | page=107 | isbn=965-264-014-X}}</ref>{{refn|Mirza Ghulam Ahmad is the founder of the [[Ahmadiyya]] sect. The [[Sunni Islam|Sunni]]-Shia mainstream and the majority of Muslims reject the Ahmadiyya sect as it believes in non-law bearing prophethood after Muhammad.}}<ref>{{Cite web|url=http://www.oxfordislamicstudies.com/article/opr/t125/e85|title=Ahmadis - Oxford Islamic Studies Online|website=www.oxfordislamicstudies.com|language=en|access-date=2018-09-03|quote=Controversial messianic movement founded by Mirza Ghulam Ahmad in Qadian, Punjab (British-controlled India), in 1889. Founder claimed to be a “nonlegislating” prophet (thus not in opposition to the mainstream belief in the finality of Muhammad's “legislative” prophecy) with a divine mandate for the revival and renewal of Islam.}}</ref> |

||

===Criticism=== |

|||

Mirza Ghulam Ahmad and his followers Ahmadis have been viewed as infidels<ref>{{Cite web|last=Imam|first=Zainab|date=2016-06-01|title=The day I declared my best friend kafir just so I could get a passport|url=http://www.dawn.com/news/1261622|access-date=2021-08-14|website=DAWN.COM|language=en}}</ref><ref>{{Cite news|last=Sayeed|first=Saad|date=2017-11-16|title=Pakistan's long-persecuted Ahmadi minority fear becoming election scapegoat|language=en|work=Reuters|url=https://www.reuters.com/article/us-pakistan-election-ahmadis-idUSKBN1DG04H|access-date=2021-08-14}}</ref> and heretics<ref>{{Cite web|last=Paracha|first=Nadeem F.|date=2013-11-21|title=The 1974 ouster of the 'heretics': What really happened?|url=http://www.dawn.com/news/1057427|access-date=2021-08-14|website=DAWN.COM|language=en}}</ref> and the movement has faced at times violent opposition.<ref>{{cite news |url=http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/south_asia/8711026.stm |title=Who are the Ahmadi? |date=28 May 2010 |work=[[BBC News]] |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20100530013220/http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/south_asia/8711026.stm |archive-date=30 May 2010 |url-status=live}}</ref><ref>{{cite book |title=When Muslims are not Muslims: The Ahmadiyya community and the discourse on heresy in Indonesia |last=Burhani |first=Ahmad Najib |publisher=[[University of California]] |year=2013 |isbn=9781303424861 |location=Santa Barbara, California |url=https://alexandria.ucsb.edu/lib/ark:/48907/f3707zhx}}</ref><ref>{{cite news |url=https://www.hindustantimes.com/newdelhi/heretical-ahmadiyya-sect-raises-muslim-hackles/article1-752846.aspx |title='Heretical' Ahmadiyya sect raises Muslim hackles |last=Haq |first=Zia |date=2 October 2011 |newspaper=[[Hindustan Times]] |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20150419082837/http://www.hindustantimes.com/newdelhi/heretical-ahmadiyya-sect-raises-muslim-hackles/article1-752846.aspx |url-status=dead |archive-date=19 April 2015 |place=New Delhi}}</ref> In 1973, the [[Organisation of Islamic Cooperation]] officially declared that the Ahmadiyya was not linked to Islam.<ref>{{Citation|last1=Harrigan|first1=Jane|title=Faith-Based Welfare and Jordan's Muslim Brotherhood Movement|date=2009|url=http://dx.doi.org/10.1057/9781137001580_4|work=Economic Liberalisation, Social Capital and Islamic Welfare Provision|pages=56–77|place=London|publisher=Palgrave Macmillan UK|isbn=978-1-349-30033-4|access-date=2021-08-14|last2=El-Said|first2=Hamed|doi=10.1057/9781137001580_4}}</ref> In Pakistan, Ahmadis have been officially declared as non-Muslims by the [[Government of Pakistan]]<ref name="2ndamend">{{cite web|title=Constitution (Second Amendment) Act, 1974|url=http://www.pakistani.org/pakistan/constitution/amendments/2amendment.html|access-date=21 January 2020|website=The Constitution of Pakistan|publisher=pakistani.org}}</ref> and the term [[Qadiani|''Qādiānī'']] is often used pejoratively to refer to them and is also used in Pakistani documents.<ref name="Gualtieri 1989 14">{{cite book |first=Antonio R. |last=Gualtieri |title=Conscience and Coercion: Ahmadis and Orthodoxy in Pakistan |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=iCwHaOabz7YC&pg=PA14 |year=1989 |publisher=Guernica Editions |isbn=978-0-920717-41-7 |page=14}}</ref> |

|||

== References == |

== References == |

||

Revision as of 09:48, 13 January 2023

A mujaddid (Arabic: مجدد), is an Islamic term for one who brings "renewal" (تجديد, tajdid) to the religion.[3][4] According to the popular Muslim tradition, it refers to a person who appears at the turn of every century of the Islamic calendar to revive Islam, cleansing it of extraneous elements and restoring it to its pristine purity. In contemporary times, a mujaddid is looked upon as the greatest Muslim of a century.[5]

The concept is based on a hadith (a saying of Islamic prophet Muhammad),[6] recorded by Abu Dawood, narrated by Abu Hurairah who mentioned that Muhammad said:

Allah will raise for this community at the end of every 100 years the one who will renovate its religion for it.

— Sunan Abu Dawood, Book 37: Kitab al-Malahim [Battles], Hadith Number 4278[7]

Ikhtilaf (disagreements) exist among different hadith viewers. Scholars such as Al-Dhahabi and Ibn Hajar al-Asqalani have interpreted that the term mujaddid can also be understood as plural, thus referring to a group of people.[8][9]

Mujaddids can include prominent scholars, pious rulers and military commanders.[4]

List of claimants and potential mujaddids

While there is no formal mechanism for designating a mujaddid in Sunni Islam, there is often a popular consensus. The Shia and Ahmadiyya[15][page needed][16] have their own list of mujaddids.[4]

First century (after the prophetic period) (August 3, 718)

- Umar ibn Abd al-Aziz (682–720)[17][18]

Second century (August 10, 815)

- Muhammad ibn Idris ash-Shafi`i (767–820)[18][19][1][20]

- Ahmad ibn Hanbal (780-855)[21]

Third century (August 17, 912)

- Muhammad al-Bukhari (810–870)[1]

- Abu al-Hasan al-Ash'ari (874–936)[19][22]

Fourth Century (August 24, 1009)

- Hakim al-Nishaburi (933–1012)[1]

- Abu Bakr Al-Baqillani (950–1013)[18][23]

Fifth century (September 1, 1106)

- Ibn Hazm (994–1064)[24]

- Abu Hamid al-Ghazali (1058–1111)[18][19][20][25][26][27][28]

- Abdul Qadir Jilani (1078-1166) [29][30]

Sixth century (September 9, 1203)

- Salauddin Ayyubi (1137–1193)[12]

- Ibn Qudamah (1147-1223)[31]

- Muhammad bin Bakhtiyar Khalji (1148-1206)[32][33]

- Fakhr al-Din al-Razi (1149–1210)[34]

Seventh century (September 5, 1300)

- Ibn Daqiq al-'Id (1228–1302) [35]

- Ibn Taymiyyah (1263–1328)[24]

- Ibn Qayyim al-Jawziyya (1292–1350)[24]

Eighth century (September 23, 1397)

- Siraj al-Din al-Bulqini (1324–1403) [36]

- Tamerlane (Timur) (1336–1405)[37]

- Ibn Hajar al-Asqalani (1372–1448)[38]

Ninth century (October 1, 1494)

Tenth century (October 19, 1591)

- Selim I (1470–1520)[40]

- Suleiman the Magnificent (1494-1566)[41]

- Ahmad Sirhindi (1564–1624)[22][42]

Eleventh century (October 26, 1688)

- Mulla Sadra Shirazi (1571–1640)[43][44]

- Khayr al-Din al-Ramli (1585–1671)[17]

- Mahiuddin Aurangzeb Alamgir (1618–1707)[45]

- Abdullah ibn Alawi al-Haddad (1634–1720)[46]

Twelfth century (November 4, 1785)

- Shah Waliullah Dehlawi (1703–1762)[45]

- Muhammad ibn Abd al-Wahhab (1703–1792)[47][failed verification]

- Murtaḍá al-Zabīdī (1732–1790)[39]

- Shah Abdul Aziz Delhwi (1745–1823)[48]

- Tipu Sultan (1750–1799)[49]

- Usman Dan Fodio (1754–1817)[50]

- Syed Ahmad Barelvi (1786–1831)[51]

- Fazl-e-Haq Khairabadi (1796–1861)[52]

Thirteenth century (November 14, 1882)

- Syed Ahmad Khan (1817–1898)[53]

- Muhammad Abduh (1849–1905)[20]

- Mahmud Hasan Deobandi (1851–1920)[54][55]

- Ahmad Raza Khan (1856–1925) [56][57]

Fourteenth century (November 21, 1979)

- Ashraf Ali Thanwi (1863–1943)[58]

- Said Nursî (1878–1960)[59]

- Abdul-Rahman al-Sa'di (1889-1957)[60]

- Abul A'la Maududi (1903–1979)[61][page needed]

- Murabit al-Hajj (1913 - 2018) [62]

- Muhammad 'Alawi al-Maliki (1944-2004) [63][64]

Claimants in other traditions

- Mirza Ghulam Ahmad (1835–1908)[65][66][67][68]

Criticism

Mirza Ghulam Ahmad and his followers Ahmadis have been viewed as infidels[69][70] and heretics[71] and the movement has faced at times violent opposition.[72][73][74] In 1973, the Organisation of Islamic Cooperation officially declared that the Ahmadiyya was not linked to Islam.[75] In Pakistan, Ahmadis have been officially declared as non-Muslims by the Government of Pakistan[76] and the term Qādiānī is often used pejoratively to refer to them and is also used in Pakistani documents.[77]

References

- ^ a b c d Waliullah, Shah. Izalatul Khafa'an Khilafatul Khulafa. p. 77, part 7.

- ^ Mohammed M. I. Ghaly, "Writings on Disability in Islam: The 16th Century Polemic on Ibn Fahd's 'al-Nukat al-Ziraf'", The Arab Studies Journal, Vol. 13/14, No. 2/1 (Fall 2005/Spring 2006), p. 26, note 98

- ^ Faruqi, Burhan Ahmad (16 August 2010). The Mujaddid's Conception of Tawhid. p. 7. ISBN 9781446164020. Retrieved 31 December 2014.

- ^ a b c Meri, Josef W., ed. (2006). Medieval Islamic Civilization: An Encyclopedia. Psychology Press. p. 678. ISBN 9780415966900.

- ^ "Mujaddid – Oxford Islamic Studies Online". www.oxfordislamicstudies.com. Retrieved 2018-09-03.

- ^ Neal Robinson (2013), Islam: A Concise Introduction, Routledge, ISBN 978-0878402243, Chapter 7, pp. 85–89

- ^ Sunan Abu Dawood, 37:4278

- ^ Fath al-Baari (13/295)

- ^ Taareekh al-Islam (23/180)

- ^ Jackson, Roy (2010). Mawlana Mawdudi and Political Islam: Authority and the Islamic State. Routledge. ISBN 9781136950360.

- ^ B. N. Pande (1996). Aurangzeb and Tipu Sultan: Evaluation of Their Religious Policies. University of Michigan. ISBN 9788185220383.

- ^ a b c Advocate of Dialogue: Fethullah Gulen by Ali Unal and Alphonse Williams, 10 June 2000; ISBN 978-0970437013

- ^ Akgunduz, Ahmed; Ozturk, Said (2011). Ottoman History - Misperceptions and Truths. IUR Press. p. 14. ISBN 978-90-90-26108-9. Retrieved 28 December 2019.

- ^ a b Hassan Ahmed Ibrahim, "An Overview of al-Sadiq al-Madhi's Islamic Discourse." Taken from The Blackwell Companion to Contemporary Islamic Thought, p. 172. Ed. Ibrahim Abu-Rabi'. Hoboken: Wiley-Blackwell, 2008. ISBN 978-1-4051-7848-8

- ^ Religion in Southeast Asia: An Encyclopedia of Faiths and Cultures. ABC-CLIO, LLC. 10 March 2015. ISBN 9781610692502.

- ^ Jesudas M. Athyal, Religion in Southeast Asia: An Encyclopedia of Faiths and Cultures, (ABC-CLIO, LLC 2015), p 1. ISBN 9781610692496.

- ^ a b c "Mujaddid Ulema". Living Islam.

- ^ a b c d Josef W. Meri, Medieval Islamic Civilization: An Encyclopedia, (Routledge 1 Dec 2005), p 678. ISBN 0415966906.

- ^ a b c Waines, David (2003). An Introduction to Islam. Cambridge University Press. p. 210. ISBN 0521539064.

- ^ a b c Nieuwenhuijze, C.A.O.van (1997). Paradise Lost: Reflections on the Struggle for Authenticity in the Middle East. p. 24. ISBN 90-04-10672-3.

- ^ Mohammed M. I. Ghaly, "Writings on Disability in Islam: The 16th Century Polemic on Ibn Fahd's "al-Nukat al-Ziraf"," The Arab Studies Journal, Vol. 13/14, No. 2/1 (Fall 2005/Spring 2006), p. 26, note 98

- ^ a b Josef W. Meri, Medieval Islamic Civilization: An Encyclopedia, (Routledge 1 Dec 2005), p 678. ISBN 0415966906

- ^ Ihya Ulum Ad Din, Dar Al Minhaj: Volume 1. p. 403.

- ^ a b c The Legal Thought of Jalāl Al-Din Al-Suyūṭī: Authority and Legacy, Page 133 Rebecca Skreslet Hernandez

- ^ "Imam Ghazali: The Sun of the Fifth century Hujjat al-Islam". The Pen. February 1, 2011.

- ^ Jane I. Smith, Islam in America, p 36. ISBN 0231519990

- ^ Dhahabi, Siyar, 4.566

- ^ Willard Gurdon Oxtoby, Oxford University Press, 1996, p 421

- ^ Reese, Scott S. (2001). "The Best of Guides: Sufi Poetry and Alternate Discourses of Reform in Early Twentieth-Century Somalia". Journal of African Cultural Studies. 14 (1 Islamic Religious Poetry in Africa): 49–68. doi:10.1080/136968101750333969. JSTOR 3181395. S2CID 162001423.

- ^ Majmu al-Fatawa, Volume 10, Page 455

- ^ "Ibn Hajar al-Asqalani - SunnahOnline.com". sunnahonline.com. Retrieved 2022-01-12.

- ^ Sufi Movements in Eastern India – Page 194

- ^ The preaching of Islam: a history of the propagation of the Muslim faith By Sir Thomas Walker Arnold, pp. 227–228

- ^ "al-Razi, Fakhr al-Din (1149–1209)". Muslim Philosophy.

- ^ Muhsin J. al-Musawi (15 April 2015). Medieval Islamic Republic of Letters, The: Arabic Knowledge Construction. University of Notre Dame Press, Chapter 6 'Disputation in Rhetoric' citation #28. ISBN 978-0268020446. ISBN 978-0268020446

- ^ Muhsin J. al-Musawi (15 April 2015). Medieval Islamic Republic of Letters, The: Arabic Knowledge Construction. University of Notre Dame Press, Chapter 6 'Disputation in Rhetoric' citation #28. ISBN 978-0268020446. ISBN 978-0268020446

- ^ Hassan Ahmed Ibrahim, "An Overview of al-Sadiq al-Madhi's Islamic Discourse." Taken from The Blackwell Companion to Contemporary Islamic Thought, p. 214. Ed. Ibrahim Abu-Rabi'. Hoboken: Wiley-Blackwell, 2008. ISBN 978-1-4051-7848-8

- ^ "Ibn Hajar Al-Asqalani". Hanafi.co.uk. Archived from the original on 2004-09-02.

- ^ a b Azra, Azyumardi (2004). The Origins of Islamic Reformism in Southeast Asia part of the ASAA Southeast Asia Publications Series. University of Hawaii Press. p. 18. ISBN 9780824828486.

- ^ Akgunduz, Ahmed; Ozturk, Said (2011). Ottoman History – Misperceptions and Truths. IUR Press. p. 14. ISBN 978-90-90-26108-9. Retrieved 28 December 2019.

- ^ Transactions of the Royal Historical Society: Volume 12: Sixth Series By Royal Historical Society

- ^ Glasse, Cyril (1997). The New Encyclopedia of Islam. AltaMira Press. p. 432. ISBN 90-04-10672-3.

- ^ The Concise Encyclopedia of Islam – Page 286

- ^ The Fundamental Principles of Mulla Sadra's Transcendent Philosophy by Reza Akbarian

- ^ a b Kunju, Saifudheen (2012). "Shah Waliullah al-Dehlawi: Thoughts and Contributions": 1. Retrieved 5 April 2015.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ "A Short Biographical Sketch of Mawlana al-Haddad". Iqra Islamic Publications. Archived from the original on 2011-05-27.

- ^ Haykel, Bernard (2013). "Ibn ‛Abd al-Wahhab, Muhammad (1703–92)". In Böwering, Gerhard; Crone, Patricia; Kadi, Wadad; Mirza, Mahan; Stewart, Devin J.; Zaman, Muhammad Qasim (eds.). The Princeton Encyclopedia of Islamic Political Thought. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. pp. 231–232. ISBN 978-0691134840.

- ^ "Gyarwee Sharif". al-mukhtar books. Archived from the original on 2012-04-26.

- ^ Muslims and India's freedom movement, Shan Muhammad, Institute of Objective Studies (New Delhi, India), Institute of Objective Studies and the University of Michigan, 2002; ISBN 9788185220581

- ^ O. Hunwick, John (1995). African And Islamic Revival in Sudanic Africa: A Journal of Historical Sources. p. 6.

- ^ Ahmad, M. (1975). Saiyid Ahmad barevali: His Life and Mission (No. 93). Lucknow: Academy of Islamic Research and Publications. Page 27.

- ^ Anil Sehgal (2001). Ali Sardar Jafri. Bharatiya Jnanpith. pp. 213–. ISBN 978-81-263-0671-8.

- ^ Encyclopedia of Islam and the Muslim World, Thompson Gale (2004)

- ^ "Shaikhul-Hind Mahmood Hasan: symbol of freedom struggle". 12 February 2016. Retrieved 3 May 2021.

- ^ Adrawi Asir. Hazrat Shaykh al-Hind: Hayāt awr kārnāme [Shaykh al-Hind: Life and works] (in Urdu). Shaykhul Hind Academy. pp. 304–305.

- ^ M.Sıddık Gümüş (1 March 2014). Islam's Reformers. Hakikat Kitabevi. ASIN B000BZYZOQ.

- ^ Dr.Muhammad Masood Ahmad (1995). The Reformer Of The Muslim World. Al-Mukhtar Publications.

- ^ Mian, Ali Altaf (2015). "Surviving Modernity: Ashraf 'Ali Thanvi (1863–1943) and the Making of Muslim Orthodoxy in Colonial India". Duke University.

- ^ Rippin, Andrew. Muslims: Their Religious Beliefs and Practices. p. 282.

- ^ Smith, Van Mitchell (September 1974). "History of West Africa, Vol. 2". History: Reviews of New Books. 2 (10): 251. doi:10.1080/03612759.1974.9946605. ISSN 0361-2759.

- ^ Mawdudi and the Making of Islamic Revivalism. Oxford University Press. 4 January 1996. ISBN 9780195357110.

- ^ Rüdiger Seesemann (2010). "Sufism in West Africa". Religion Compass. 4 (10). Blackwell Publishing Ltd: 606–614. doi:10.1111/j.1749-8171.2010.00241.x.

- ^ "next mujaddid- Syekh Muhammad Alawi al-Maliki, Benteng Sunni Abad ke-21". Republika (Indonesian newspaper) (in Indonesian). 2015-03-02. Retrieved 2020-06-08.

- ^ Jalali. "Correct Understanding of the Mawlid – 1 | TAQWA.sg | Tariqatu-l Arusiyyatu-l Qadiriyyah Worldwide Association (Singapore) - Shari'a, Tariqa, Ma'rifa, and Haqiqa". Retrieved 2020-06-08.

- ^ Adil Hussain Khan, From Sufism to Ahmadiyya: A Muslim Minority Movement in South Asia, Indiana University Press, 6 April 2015, p. 42.

- ^ Friedmann, Yohanan (2003). Prophecy Continuous: Aspects of Ahmadi Religious Thought and Its Medieval Background. Oxford University Press. p. 107. ISBN 965-264-014-X.

- ^ Mirza Ghulam Ahmad is the founder of the Ahmadiyya sect. The Sunni-Shia mainstream and the majority of Muslims reject the Ahmadiyya sect as it believes in non-law bearing prophethood after Muhammad.

- ^ "Ahmadis - Oxford Islamic Studies Online". www.oxfordislamicstudies.com. Retrieved 2018-09-03.

Controversial messianic movement founded by Mirza Ghulam Ahmad in Qadian, Punjab (British-controlled India), in 1889. Founder claimed to be a "nonlegislating" prophet (thus not in opposition to the mainstream belief in the finality of Muhammad's "legislative" prophecy) with a divine mandate for the revival and renewal of Islam.

- ^ Imam, Zainab (2016-06-01). "The day I declared my best friend kafir just so I could get a passport". DAWN.COM. Retrieved 2021-08-14.

- ^ Sayeed, Saad (2017-11-16). "Pakistan's long-persecuted Ahmadi minority fear becoming election scapegoat". Reuters. Retrieved 2021-08-14.

- ^ Paracha, Nadeem F. (2013-11-21). "The 1974 ouster of the 'heretics': What really happened?". DAWN.COM. Retrieved 2021-08-14.

- ^ "Who are the Ahmadi?". BBC News. 28 May 2010. Archived from the original on 30 May 2010.

- ^ Burhani, Ahmad Najib (2013). When Muslims are not Muslims: The Ahmadiyya community and the discourse on heresy in Indonesia. Santa Barbara, California: University of California. ISBN 9781303424861.

- ^ Haq, Zia (2 October 2011). "'Heretical' Ahmadiyya sect raises Muslim hackles". Hindustan Times. New Delhi. Archived from the original on 19 April 2015.

- ^ Harrigan, Jane; El-Said, Hamed (2009), "Faith-Based Welfare and Jordan's Muslim Brotherhood Movement", Economic Liberalisation, Social Capital and Islamic Welfare Provision, London: Palgrave Macmillan UK, pp. 56–77, doi:10.1057/9781137001580_4, ISBN 978-1-349-30033-4, retrieved 2021-08-14

- ^ "Constitution (Second Amendment) Act, 1974". The Constitution of Pakistan. pakistani.org. Retrieved 21 January 2020.

- ^ Gualtieri, Antonio R. (1989). Conscience and Coercion: Ahmadis and Orthodoxy in Pakistan. Guernica Editions. p. 14. ISBN 978-0-920717-41-7.

Further reading

- Alvi, Sajida S. "The Mujaddid and Tajdīd Traditions in the Indian Subcontinent: An Historical Overview" ("Hindistan’da Mucaddid ve Tacdîd geleneği: Tarihî bir bakış"). Journal of Turkish Studies 18 (1994): 1–15.

- Friedmann, Yohanan. Shaykh Ahmad Sirhindi: An Outline of His Thought and a Study of His Image in the Eyes of Posterity. Oxford India Paperbacks