Zviad Gamsakhurdia: Difference between revisions

m Dating maintenance tags: {{Refnec}} |

მითები ზვიად გამსახურდიას შესახებ is not a reliable source: it's the blog section of the Georgian language edition of RFE: "ძვირფასო მეგობრებო, რადიო თავისუფლების რუბრიკაში „თავისუფალი სივრცე“ შეგიძლიათ საკუთარი ბლოგებისა და პუბლიცისტური სტატიების გამოქვეყნება." "თავისუფალი სივრცე – თქვენი პუბლიკაციებისთვის" |

||

| Line 83: | Line 83: | ||

A three-way power struggle between Georgian, Ossetian and Soviet military forces broke out in the region, which resulted (by March 1991) in the deaths of 51 people and the eviction from their homes of 25,000 more. After his election as chairman of the newly renamed Supreme Council, Gamsakhurdia denounced the Ossetian move as being part of a Russian ploy to undermine Georgia, declaring the Ossetian separatists to be "direct agents of the Kremlin, its tools and terrorists." In February 1991, he sent a letter to [[Mikhail Gorbachev]] demanding the withdrawal of Soviet army units and an additional contingent of interior troops of the USSR from the territory of the former Autonomous District of [[South Ossetia]].{{refnec|date=October 2023}} |

A three-way power struggle between Georgian, Ossetian and Soviet military forces broke out in the region, which resulted (by March 1991) in the deaths of 51 people and the eviction from their homes of 25,000 more. After his election as chairman of the newly renamed Supreme Council, Gamsakhurdia denounced the Ossetian move as being part of a Russian ploy to undermine Georgia, declaring the Ossetian separatists to be "direct agents of the Kremlin, its tools and terrorists." In February 1991, he sent a letter to [[Mikhail Gorbachev]] demanding the withdrawal of Soviet army units and an additional contingent of interior troops of the USSR from the territory of the former Autonomous District of [[South Ossetia]].{{refnec|date=October 2023}} |

||

According to [[George Khutsishvili]], the nationalist "Georgia for the Georgians" hysteria launched by the followers of Gamsakhurdia, part of the [[Round Table—Free Georgia]] coalition, "played a decisive role" in "bringing about Bosnia-like inter-ethnic violence."<ref name=hrw1992/><ref>{{cite journal|url=https://open.bu.edu/handle/2144/3502 |language=en-US|title=Intervention in Transcaucasus|last=Khutsishvili |first=George|publisher=Perspective|volume=4|issue=3|date= February–March 1994|journal=[[Boston University]]}}</ref> His ethnoreligious [[chauvinism]] increased tensions between [[ethnic minorities in Georgia (country)|ethnic minorities in Georgia]].<ref>{{Cite book |last=Zakharov |first=Nikolay |title=Post-Soviet racisms |last2=Law |first2=Ian |date=2017 |publisher=Palgrave Macmillan |isbn=978-1-137-47691-3 |series=Mapping global racisms |location=London|p=118}}</ref> The [[Carnegie Endowment for International Peace]] notes that Gamsakhurdia's [[Anti-Ossetian sentiment|anti-Ossetian]] discourse is one of the main causes of the [[Georgian–Ossetian conflict]].<ref>{{cite web|url=https://carnegieeurope.eu/2021/04/27/struggle-and-sacrifice-narratives-of-georgia-s-modern-history-pub-84391|title=Struggle and Sacrifice: Narratives of Georgia’s Modern History|date=2021-04-27|first=Katie|last=Sartania|website=[[Carnegie Europe]]}}</ref> |

|||

A slogan "Georgia for the Georgians" has been falsely attributed to Zviad Gamsakhurdia. However, it has never been used by him or his allies. It was a slogan of [[Giorgi Chanturia|Gia Chanturia]] and his political party [[National Democratic Party (Georgia)|National Democratic Party]], which was in opposition to Gamsakhurdia's presidency. According to Chanturia, "Georgia for Georgians" was not a slogan directed against ethnic minorities, but a slogan to support Georgia's pro-independence movement. The slogan was also falsely attributed to Gamsakhurdia by then Russian President [[Dmitry Medvedev]].<ref>{{cite web|url=https://www.radiotavisupleba.ge/a/tavisupali-sivrtse-giorgi-arkania-mitebi-zviad-gamvakhurdiaze/28400373.html|title=მითები ზვიად გამსახურდიას შესახებ|date=2021-04-27|website=[[Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty|Radio Liberty]]|language=Georgian|quote="To this day, many people think that the slogan "Georgia for Georgians" belongs to Zviad Gamsakhurdia, however, he has never used such a phrase in any statement or rally. Actually, this call was written in the program document of Giorgi Chanturia's "National Democratic Party". Chanturia then explained that "Georgia for Georgians" was not a slogan against ethnic minorities. The situation changed so much that he and his supporters "congratulated" Gamsakhurdia with this slogan and baptized him as an enemy of other ethnic groups."}}</ref> |

|||

===Human rights violations criticism=== |

===Human rights violations criticism=== |

||

Revision as of 07:43, 6 October 2023

This article includes a list of general references, but it lacks sufficient corresponding inline citations. (May 2011) |

Zviad Gamsakhurdia | |

|---|---|

| ზვიად გამსახურდია | |

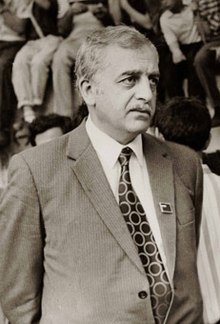

Gamsakhurdia in 1989 | |

| 1st President of Georgia | |

| In office 26 May 1991 – 6 January 1992 | |

| Prime Minister | Murman Omanidze (Acting) Besarion Gugushvili |

| Preceded by | Office established |

| Succeeded by | Eduard Shevardnadze (1995) |

| Chairman of the Supreme Council of Georgia | |

| In office 14 November 1990 – 26 May 1991 | |

| Preceded by | Irakli Abashidze |

| Succeeded by | Himself as the Head of state; Akaki Asatiani as the Chairman of the Parliament of Georgia |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 31 March 1939 Tbilisi, Georgian SSR, Soviet Union |

| Died | 31 December 1993 (aged 54) Dzveli Khibula, Georgia |

| Political party | Round Table—Free Georgia |

| Spouse(s) |

Dali Lolua (divorced)Manana Archvadze-Gamsakhurdia |

| Signature | |

Zviad Konstantines dze Gamsakhurdia[1] (Georgian: ზვიად კონსტანტინეს ძე გამსახურდია; Russian: Звиа́д Константи́нович Гамсаху́рдия, romanized: Zviad Konstantinovich Gamsakhurdiya; 31 March 1939 – 31 December 1993) was a Georgian politician, dissident, scholar, and writer who became the first democratically elected President of Georgia in the post-Soviet era.

A prominent exponent of Georgian nationalism and pan-Caucasianism, Zviad Gamsakhurdia was involved in Soviet dissident movement from his early teens. In 1953, he was one of the founders of Gorgasliani, a nationalist group, which disseminated anti-Soviet proclamations in Tbilisi. His activities attracted attention of Soviet intelligence, and Gamsakhurdia was arrested and sent to imprisonment, although he was soon pardoned and released from jail. Gamsakhurdia co-founded the Georgian Helsinki Group, which sought to bring attention to human rights violations in the Soviet Union. He organized numerous pro-independence protests in Georgia, one of which in 1989 was suppressed by the Soviet Army, with Gamsakhurdia being arrested. Eventually, a number of underground political organizations united around Zviad Gamsakhurdia and formed the Round Table—Free Georgia coalition, which successfully challenged the ruling Communist Party of Georgia in the 1990 elections. Gamsakhurdia was elected as the President of Georgia in 1991, gaining 87% of votes in the election. Despite popular support, Gamsakhurdia found significant opposition from the urban intelligentsia and former Soviet nomenklatura, as well as from his own ranks. In early 1992 Gamsakhurdia was overthrown by warlords Tengiz Kitovani, Jaba Ioseliani and Tengiz Sigua, two of which were formerly allied with Gamsakhurdia. Gamsakhurdia was forced to flee to Chechnya, where he was greeted by Chechen president Dzhokhar Dudayev. His supporters continued to fight the post-coup government of Eduard Shevardnadze. In September 1993, Gamsakhurdia returned to Georgia and tried to regain power. Despite initial success, the rebellion was eventually crushed by government forces with the help of the Russian military. Gamsakhurdia was forced into hiding in Samegrelo, a Zviadist stronghold. He was found dead in early 1994 in controversial circumstances. His death remains uninvestigated to this day.

After the civil war ended, the government continued to suppress Gamsakhurdia's supporters, even with brutal tactics. He was rehabilitated by the President Mikheil Saakashvili and awarded the title and Order of National Hero of Georgia. Government officials as well as people pay tribute to memory of Zviad Gamsakhurdia every year on his birthday.[2] He has been named as a 3rd "Greatest Georgian" by a TV programme "100 Greatest Georgians" launched by First Channel of Georgia.

Gamsakhurdia was a prominent proponent of Georgian nationalism. He campaigned against what he considered as the demographic replacement of ethnic Georgians by Communist authorities, artificial increasing of ethnic minority population in Georgia and discrimination of Georgians. Gamsakhurdia also promoted pan-Caucasian views and unity of the peoples of the Caucasus in the face of Russian imperialism. Gamsakhurdia considered Georgians to be inherently European nation and belonging to the European civilization.

Gamsakhurdia as dissident

Early career

Zviad Gamsakhurdia was born in the Georgian capital Tbilisi in 1939, in a distinguished Georgian family; his father, Academician Konstantine Gamsakhurdia (1893–1975), was one of the most famous Georgian writers of the 20th century. Perhaps influenced by his father, Zviad received training in philology and began a professional career as a translator and literary critic.[citation needed]

In 1955, Zviad Gamsakhurdia established a youth underground group which he called the Gorgasliani (a reference to the ancient line of Georgian kings) which sought to circulate reports of human rights abuses. In 1956, he was arrested during demonstrations in Tbilisi against the Soviet policy of de-stalinization and was arrested again in 1958 for distributing anti-communist literature and proclamations. He was confined for six months to a mental hospital in Tbilisi, where he was diagnosed as suffering from "psychopathy with decompensation", thus perhaps becoming an early victim of what became a widespread policy of using psychiatry for political purposes.[citation needed]

Human rights activism

Gamsakhurdia achieved wider prominence in 1972 during a campaign against the corruption associated with the appointment of a new Catholicos of the Georgian Orthodox Church, of which he was a "fervent" adherent[3]

In 1973 he co-founded the Georgian Action Group for the Defense of Human Rights (four years earlier a Moscow-based group of that name sent an appeal to the UN Human Rights Committee);[4] in 1974 he became the first Georgian member of Amnesty International; and in 1976 he co-founded and became chairman of the Georgian Helsinki Group.[5] He was also active in the underground network of samizdat publishers, contributing to a wide variety of underground political periodicals: among them were Okros Satsmisi ("The Golden Fleece"), Sakartvelos Moambe ("The Georgian Herald"), Sakartvelo ("Georgia"), Matiane ("Annals") and Vestnik Gruzii. He contributed to the Moscow-based underground periodical Chronicle of Current Events (April 1968 – December 1982). Gamsakhurdia was also the first Georgian member of the International Society for Human Rights (ISHR-IGFM).[citation needed]

Perhaps seeking to emulate his father,[citation needed] Zviad Gamsakhurdia also pursued a distinguished academic career. He was a senior research fellow of the Institute of Georgian Literature of the Georgian Academy of Sciences (1973–1977, 1985–1990), associate professor of the Tbilisi State University (1973–1975, 1985–1990) and member of the Union of Georgia's Writers (1966–1977, 1985–1991), PhD in the field of Philology (1973) and Doctor of Sciences (Full Doctor, 1991). He wrote a number of important literary works, monographs and translations of British, French and American literature, including translations of works by T. S. Eliot, William Shakespeare, Charles Baudelaire and Oscar Wilde. He was also an outstanding Rustvelologist (Shota Rustaveli was a great Georgian poet of the 12th century) and researcher of history of the Iberian-Caucasian culture.[citation needed]

Although he was frequently harassed and occasionally arrested for his dissidence, for a long time Gamsakhurdia avoided serious punishment, probably as a result of his family's prestige and political connections. His luck ran out in 1977 when the activities of the Helsinki Groups in the Soviet Union became a serious embarrassment to the Soviet government of Leonid Brezhnev. A nationwide crackdown on human rights activists was instigated across the Soviet Union and members of the Helsinki Groups in Moscow, Lithuania, Ukraine, Armenia and Georgia were arrested.[6]

In Georgia, the government of Eduard Shevardnadze (who was then First Secretary of the Georgian Communist Party) arrested Gamsakhurdia and his fellow dissident Merab Kostava on 7 April 1977.[7]

Trial, 15–19 May 1978

There remains some dispute about Gamsakhurdia's behaviour or strategy during his pre-trial detention and the trial itself. In particular, this concerns a TV broadcast in which, apparently, he recanted his activities as a human rights activist.[citation needed]

A contemporary and uncensored account of these events may be found in the Chronicle of Current Events.[8] The two men were sentenced to three years in the camps plus three years' exile for "anti-Soviet activities". Gamsakhurdia did not appeal but his sentence was commuted to two years' exile in neighbouring Dagestan.[8] Their imprisonment attracted international attention.[9]

Kostava's appeal was rejected and he was sent to a penal colony for three years, followed by three years' exile or internal banishment to Siberia. Kostava's sentence only ended in 1987. At the end of June 1979, Gamsakhurdia was released from jail and pardoned in controversial circumstances. By then, taking pre-trial detention into account, he had served two years of his sentence.[citation needed]

The authorities claimed that he had confessed to the charges and recanted his beliefs; a film clip was shown on Soviet television to substantiate their claim.[10] According to a transcript published by the Soviet news agency TASS, Gamsakhurdia spoke of "how wrong was the road I had taken when I disseminated literature hostile to the Soviet state. Bourgeois propaganda seized upon my mistakes and created a hullabaloo around me, which causes me pangs of remorse. I have realized the essence of the pharisaic campaign launched in the West, camouflaged under the slogan of 'upholding human rights.'"[citation needed]

His supporters, family and Merab Kostava claimed that his recantation was coerced by the KGB, and although he publicly acknowledged that certain aspects of his anti-Soviet endeavors were mistaken, he did not renounce his leadership of the dissident movement in Georgia. Perhaps more importantly, his actions ensured that the dissident leadership could remain active. Kostava and Gamsakhurdia later both independently stated that the latter's recantation had been a tactical move. In an open letter to Shevardnadze, dated 19 April 1992, Gamsakhurdia claimed that "my so-called confession was necessitated ... [because] if there had been no 'confession' and my release from the prison in 1979 had not taken place, then there would not have been a rise of the national movement."[11]

Gamsakhurdia returned to dissident activities soon after his release, continuing to contribute to samizdat periodicals and campaigning for the release of Merab Kostava. In 1981 he became the spokesman of the students and others who protested in Tbilisi about the threats to Georgian identity and the Georgian cultural heritage. He handed a set of "Demands of the Georgian People" to Shevardnadze outside the Congress of the Georgian Writers Union at the end of March 1981, which earned him another spell in jail.[citation needed]

Moves towards independence

When the Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev initiated his policy of glasnost, Gamsakhurdia played a key role in organizing mass pro-independence rallies held in Georgia between 1987 and 1990, in which he was joined by Merab Kostava on the latter's release in 1987. In 1988, Gamsakhurdia became one of the founders of the Society of Saint Ilia the Righteous (SSIR), a combination of a religious society and a political party which became the basis for his own political movement. The following year, the brutal suppression by Soviet forces of a large peaceful demonstration held in Tbilisi on 4–9 April 1989 proved to be a pivotal event in discrediting the continuation of Soviet rule over the country. The progress of democratic reforms was accelerated and led to Georgia's first democratic multiparty elections, held on 28 October 1990. Gamsakhurdia's SSIR party and the Georgian Helsinki Union joined with other opposition groups to head a reformist coalition called "Round Table — Free Georgia" ("Mrgvali Magida — Tavisupali Sakartvelo"). The coalition won a convincing victory, with 64% of the vote, as compared with the Georgian Communist Party's 29.6%. On 14 November 1990, Zviad Gamsakhurdia was elected by an overwhelming majority as chairman of the Supreme Council of the Republic of Georgia.[citation needed]

Georgia held a referendum on restoring its pre-Soviet independence on 31 March 1991 in which 98.9% of those who voted declared in its favour. The Georgian parliament passed a declaration of independence on 9 April 1991, in effect restoring the 1918–1921 Georgian Sovereign state. However, it was not recognized by the Soviet Union and although a number of foreign powers granted early recognition, universal recognition did not come until the following year. Gamsakhurdia was elected president in the election of 26 May with 86.5% per cent of the vote on a turnout of over 83%.[citation needed]

Gamsakhurdia as president

On taking office, Gamsakhurdia was faced with major economic and political difficulties, especially regarding Georgia's relations with the Soviet Union. A key problem was the position of Georgia's many ethnic minorities (making up 30% of the population). Although minority groups had participated actively in Georgia's return to democracy, they were underrepresented in the results of the October 1990 elections with only nine of 245 deputies being non-Georgians. Even before Georgia's independence, the position of national minorities was contentious and led to outbreaks of serious inter-ethnic violence in Abkhazia during 1989.[citation needed]

In 1989, violent unrest broke out in South Ossetian Autonomous Oblast between the Georgian independence-minded population of the region and Ossetians loyal to the Soviet Union. South Ossetia's regional soviet announced that the region would secede from Georgia to form a "Soviet Democratic Republic". In response, the Supreme Soviet of the Georgian SSR annulled the autonomy of South Ossetia in March 1990.[12]

A three-way power struggle between Georgian, Ossetian and Soviet military forces broke out in the region, which resulted (by March 1991) in the deaths of 51 people and the eviction from their homes of 25,000 more. After his election as chairman of the newly renamed Supreme Council, Gamsakhurdia denounced the Ossetian move as being part of a Russian ploy to undermine Georgia, declaring the Ossetian separatists to be "direct agents of the Kremlin, its tools and terrorists." In February 1991, he sent a letter to Mikhail Gorbachev demanding the withdrawal of Soviet army units and an additional contingent of interior troops of the USSR from the territory of the former Autonomous District of South Ossetia.[citation needed]

According to George Khutsishvili, the nationalist "Georgia for the Georgians" hysteria launched by the followers of Gamsakhurdia, part of the Round Table—Free Georgia coalition, "played a decisive role" in "bringing about Bosnia-like inter-ethnic violence."[13][14] His ethnoreligious chauvinism increased tensions between ethnic minorities in Georgia.[15] The Carnegie Endowment for International Peace notes that Gamsakhurdia's anti-Ossetian discourse is one of the main causes of the Georgian–Ossetian conflict.[16]

Human rights violations criticism

On 27 December 1991, the U.S. based NGO Helsinki Watch issued a report on human rights violations made by the government of Gamsakhurdia.[17] The report included information on documented freedom of assembly, freedom of speech, freedom of the press violations in Georgia, on political imprisonment, human rights abuses by the Georgian government and paramilitary in South Ossetia, and other human rights violations. In a report published in April 1992, Human Rights Watch noted that Gamsakhurdia had "quasi-dictatorial powers".[13]

The rise of the opposition

Gamsakhurdia's opponents were highly critical of what they regarded as "unacceptably dictatorial behaviour", which had already been the subject of criticism even before his election as president. Prime Minister Tengiz Sigua and two other senior ministers resigned on August 19 in protest against Gamsakhurdia's policies. The three ministers joined the opposition, accusing him of "being a demagogue and totalitarian" and complaining about the slow pace of economic reform. In an emotional television broadcast, Gamsakhurdia claimed that his enemies were engaging in "sabotage and betrayal" within the country.[citation needed]

Gamsakhurdia's response to the coup against President Gorbachev was a source of further controversy. On 19 August, Gamsakhurdia, the Georgian government, and the Presidium of the Supreme Council issued an appeal to the Georgian population to remain calm, stay at their workplaces, and perform their jobs without yielding to provocations or taking unauthorized actions. The following day, Gamsakhurdia appealed to international leaders to recognize the republics (including Georgia) that had declared themselves independent of the Soviet Union and to recognise all legal authorities, including the Soviet authorities deposed by the coup.[citation needed]

This article may be confusing or unclear to readers. In particular, Did Gamsakhuria support or opposed the coup leaders?. (August 2016) |

He claimed publicly on 21 August that Gorbachev himself had masterminded the coup in an attempt to boost his popularity before the Soviet presidential elections, an allegation rejected as "ridiculous" by US President George H. W. Bush.[citation needed]

In a particularly controversial development, the Russian news agency Interfax reported that Gamsakhurdia had agreed with the Soviet military that the Georgian National Guard would be disarmed, and on 23 August, he issued decrees abolishing the post of commander of the Georgian National Guard and redesignating its members as interior troops subordinate to the Georgian Ministry of Internal Affairs. In reality, the National Guard was already a part of the Ministry of the Interior, and Gamsakhurdia's opponents, who claimed he was seeking to abolish it, were asked to produce documents they claimed they possessed which verified their claims, but did not do so. Gamsakhurdia always maintained he had no intention of disbanding the National Guard.[18] In defiance of the alleged order of Gamskhurdia, the sacked National Guard commander Tengiz Kitovani led most of his troops out of Tbilisi on 24 August. By this time, however, the coup had clearly failed and Gamsakhurdia publicly congratulated Russia's President Boris Yeltsin on his victory over the putschists.[19] Georgia had survived the coup without any violence, but Gamsakhurdia's opponents accused him of not being resolute in opposing it.[citation needed]

Gamsakhurdia reacted angrily, accusing shadowy forces in Moscow of conspiring with his internal enemies against Georgia's independence movement. In a rally in early September, he told his supporters: "The infernal machinery of the Kremlin will not prevent us from becoming free.... Having defeated the traitors, Georgia will achieve its ultimate freedom." He shut down an opposition newspaper, "Molodiozh Gruzii," on the grounds that it had published open calls for a national rebellion. Giorgi Chanturia, whose National Democratic Party was one of the most active opposition groups at that time, was arrested and imprisoned on charges of seeking help from Moscow to overthrow the legal government. It was also reported that Channel 2, a television station, was closed down after employees took part in rallies against the government.[20]

The government's activities aroused controversy at home and strong criticism abroad. A visiting delegation of US Congressmen led by Representative Steny Hoyer reported that there were "severe human rights problems within the present new government, which is not willing to address them or admit them or do anything about them yet." American commentators cited the human rights issue as being one of the main reasons for Georgia's inability to secure widespread international recognition. The country had already been granted recognition by a limited number of countries (including Romania, Turkey, Canada, Finland, Ukraine, Lithuania, Latvia, Estonia and others) but recognition by major countries, including the U.S., Sweden, Switzerland, France, Belgium, Pakistan, India, came only during Christmas of 1991.[citation needed]

The political dispute turned violent on September 2, when an anti-government demonstration in Tbilisi was dispersed by police. The most ominous development was the splintering of the Georgian National Guard into pro- and anti-government factions, with the latter setting up an armed camp outside the capital. Skirmishes between the two sides occurred across Tbilisi during October and November with occasional fatalities resulting from gunfights. Paramilitary groups — one of the largest of which was the anti-Gamsakhurdia "Mkhedrioni" ("Horsemen" or "Knights"), a nationalist militia with several thousand members — set up barricades around the city.[citation needed]

Coup d'état

On 22 December 1991, armed opposition supporters launched a violent coup d'état and attacked a number of official buildings including the Georgian parliament building, where Gamsakhurdia himself was sheltering. Heavy fighting continued in Tbilisi until 6 January 1992, leaving hundreds dead and the centre of the city heavily damaged. On 6 January, Gamsakhurdia and members of his government escaped through opposition lines and made their way to Azerbaijan where they were denied asylum. Armenia finally hosted Gamsakhurdia for a short period and rejected Georgian demands to extradite Gamsakhurdia back to Georgia. In order not to complicate tense relations with Georgia, Armenian authorities allowed Gamsakhurdia to move to the breakaway Russian republic of Chechnya, where he was granted asylum by the rebel government of General Dzhokhar Dudayev.[21]

It was later claimed that Russian forces had been involved in the coup against Gamsakhurdia. On 15 December 1992 the Russian newspaper Moskovskiye Novosti printed a letter claiming that the former Vice-Commander of the Transcaucasian Military District, Colonel General Sufian Bepayev, had sent a "subdivision" to assist the armed opposition. If the intervention had not taken place, it was claimed, "Gamsakhurdia supporters would have been guaranteed victory." It was also claimed that Soviet special forces had helped the opposition to attack the state television tower on 28 December.[citation needed]

A Military Council made up of Gamsakhurdia opponents took over the government on an interim basis. One of its first actions was to formally depose Gamsakhurdia as president. It reconstituted itself as a State Council and, without any formal referendum or election, in March 1992 appointed Gamsakhurdia's old rival Eduard Shevardnadze as chairman, who then ruled as de facto president until the formal restoration of the presidency in November 1995.[citation needed]

Gamsakhurdia in exile

After his overthrow, Gamsakhurdia continued to promote himself as the legitimate president of Georgia. He was still recognized as such by some governments and international organizations, although as a matter of pragmatic politics the insurrectionist Military Council was quickly accepted as the governing authority in the country. Gamsakhurdia himself refused to accept his ouster, not least because he had been elected to the post with an overwhelming majority of the popular vote (in conspicuous contrast to the undemocratically appointed Shevardnadze).[citation needed] In November–December 1992, he was invited to Finland (by the Georgia Friendship Group of the Parliament of Finland) and Austria (by the International Society for Human Rights). In both countries, he held press conferences and meetings with parliamentarians and government officials[22]

Clashes between pro- and anti-Gamsakhurdia forces continued throughout 1992 and 1993 with Gamsakhurdia supporters taking captive government officials and government forces retaliating with reprisal raids. One of the most serious incidents occurred in Tbilisi on 24 June 1992, when armed Gamsakhurdia supporters seized the state television center. They managed to broadcast a radio message declaring that "The legitimate government has been reinstated. The red junta is nearing its end." However, they were driven out within a few hours by the National Guard. They may have intended to prompt a mass uprising against the Shevardnadze government, but this did not materialize.[citation needed]

Shevardnadze's government imposed a harshly repressive regime throughout Georgia to suppress "Zviadism", with security forces and the pro-government Mkhedrioni militia carrying out widespread arrests and harassment of Gamsakhurdia supporters. Although Georgia's poor human rights record was strongly criticized by the international community, Shevardnadze's personal prestige appears to have convinced them to swallow their doubts and grant the country formal recognition. Government troops moved into Abkhazia in September 1992 in an effort to root out Gamsakhurdia's supporters among the Georgian population of the region, but well-publicized human rights abuses succeeded only in worsening already poor ethnic relations. Later, in September 1993, a full-scale war broke out between Georgian forces and Abkhazian separatists. This ended in a decisive defeat for the government, with government forces and 300,000 Georgians being driven out of Abkhazia and an estimated 10,000 people being killed in the fighting.[citation needed]

1993 civil war

Gamsakhurdia soon took up the apparent opportunity to bring down Shevardnadze. He returned to Georgia on 24 September 1993, a couple of days before the ultimate Fall of Sukhumi, establishing a "government in exile" in the western Georgian city of Zugdidi. He announced that he would continue "the peaceful struggle against an illegal military junta" and concentrated on building an anti-Shevardnadze coalition, drawing on the support of the regions of Samegrelo (Mingrelia) and Abkhazia. He also built up a substantial military force that was able to operate relatively freely in the face of the weak security forces of the state. After initially demanding immediate elections, Gamsakhurdia took advantage of the Georgian army's rout to seize large quantities of weapons abandoned by the retreating governmental forces. A civil war engulfed western Georgia in October 1993 as Gamsakhurdia's forces succeeded in capturing several key towns and transport hubs. Government forces fell back in disarray, leaving few obstacles between Gamsakhurdia's forces and Tbilisi. However, Gamsakhurdia's capture of the economically vital Georgian Black Sea port of Poti threatened the interests of Russia, Armenia (totally landlocked and dependent on Georgia's ports) and Azerbaijan. In an apparent and very controversial quid pro quo, all three countries expressed their support for Shevardnadze's government, which in turn agreed to join the Commonwealth of Independent States. While the support from Armenia and Azerbaijan was purely political, Russia quickly mobilized troops to aid the Georgian government. On 20 October around 2,000 Russian troops moved to protect Georgian railroads and provided logistical support and weapons to the poorly armed government forces. The uprising quickly collapsed and Zugdidi fell on 6 November.[citation needed]

Gamsakhurdia's death

On 31 December 1993, Zviad Gamsakhurdia died in circumstances that are still unclear. It is known that he died in the village of Dzveli Khibula in the Samegrelo region of western Georgia and later was re-buried in the village of Jikhashkari (also in the Samegrelo region). According to British press reports, his body was found with a single bullet wound to the head but, in fact, it was found with two bullet wounds to the head. A variety of reasons has been given for his death, which is still controversial and remains unresolved.[citation needed]

Years later Avtandil Ioseliani - counter-intelligence head of interim government - admitted that two special units were hunting Zviad on interim government's orders.[23]

In the first days of December 1993 two members of President's personal guard also disappeared without a trace, after being sent on a scout mission.[24][23] Some remains and ashes, never identified, were found 17 years later.[24]

Assassination

According to former deputy director of Biopreparat Ken Alibek, that laboratory was possibly involved in the design of an undetectable chemical or biological agent to assassinate Gamsakhurdia.[25] BBC News reported that some of Gamsakhurdia's friends believed he committed suicide, "although his widow insists that he was murdered."[26]

Suicide

Gamsakhurdia's widow later told the Interfax news agency that her husband shot himself on 31 December when he and a group of colleagues found the building where he was sheltering surrounded by forces of the pro-Shevardnadze Mkhedrioni militia. The Russian media reported that his bodyguards heard a muffled shot in the next room and found that Gamsakhurdia had killed himself with a shot to the head from a Stechkin pistol. The Chechen authorities published what they claimed was Gamsakhurdia's suicide note: "Being in clear state of mind, I commit this act in token of protest against the ruling regime in Georgia and because I am deprived of the possibility, acting as the president, to normalize the situation, and to restore law and order."[citation needed]

Died in infighting

The Georgian Interior Ministry under Shevardnadze's regime suggested that he had either been deliberately killed by his own supporters, or died following a quarrel with his former chief commander, Loti Kobalia.[citation needed]

Gamsakhurdia's death was announced by the Georgian government on January 5, 1994. Some refused to believe that Gamsakhurdia had died at all but the question was eventually settled when his body was recovered on 15 February 1994. Zviad Gamsakhurdia's remains were re-buried in the Chechen capital Grozny on 17 February 1994.[27] On 3 March 2007, the newly appointed president of Chechnya Ramzan Kadyrov announced that Gamsakhurdia's grave – lost in the debris and chaos of a war-ravaged Grozny – had been found in the center of the city. Gamsakhurdia's remains were identified by Russian experts in Rostov-on-Don, and arrived in Georgia on 28 March 2007, for reburial. He was interred alongside other prominent Georgians at the Mtatsminda Pantheon on 1 April 2007.[28] Thousands of people throughout Georgia had arrived in Mtskheta's medieval cathedral to pay tribute to Gamsakhurdia.[29] "We are implementing the decision which was [taken] in 2004 – to bury President Gamsakhurdia on his native soil. This is a fair and absolutely correct decision," President Mikheil Saakashvili told reporters, the Civil Georgia internet news website reported on 31 March.[citation needed]

Investigation into death

On 14 December 2018, Constantine and Tsotne Gamsakhurdia, the former president's two sons, announced concerns about the expiration of the statute of limitations set at the end of the same year for a potential investigation into the death of their father, as Georgian law set a 25-year limit for serious crime investigations. They then announced the beginning of a hunger strike.[citation needed]

On 21 December, newly inaugurated President Salome Zurabishvili formally endorsed the request to expand the statute of limitations, calling Gamsakhurdia's death a “murder”, a move supported by opposition and ruling party members of Parliament. Less than a week later, Parliament approved a bill to expand the statute of limitations for serious crimes from 25 to 30 years after the crime, following Constantine Gamsakhurdia's hospitalization.[citation needed]

On 26 December, following the setting-up of a new investigative group under the leadership of General Prosecutor Shalva Tadumadze, Tsotne Gamsakhurdia ended his hunger strike, thus promising a new investigation into his father's death.[citation needed]

Personal life

Gamsakhurdia was married twice. He and his first wife, Dali Lolua, had one son, Konstantine Gamsakhurdia.[citation needed]

Gamsakhurdia's second wife, Manana Archvadze-Gamsakhurdia, was the inaugural First Lady of independent Georgia.[30] The couple had two sons, Tsotne and Giorgi.[30]

Gamsakhurdia was a proponent of Georgian messianism: the "spiritual mission of Georgia" to be a moral example to the rest of the world. He believed that he was divinely appointed by God to lead Georgia.[31][32][33]

Legacy

On 26 January 2004, in a ceremony held at the Kashueti Church of Saint George in Tbilisi, the newly elected President Mikheil Saakashvili officially rehabilitated Gamsakhurdia to resolve the lingering political effects of his overthrow in an effort to "put an end to disunity in our society", as Saakashvili put it. He praised Gamsakhurdia's role as a "great statesman and patriot" and promulgated a decree granting permission for Gamsakhurdia's body to be reburied in the Georgian capital, declaring that the "abandon[ment of] the Georgian president's grave in a war zone ... is a shame and disrespectful of one's own self and disrespectful of one's own nation". He also renamed a major road in Tbilisi after Gamsakhurdia and released 32 Gamsakhurdia supporters imprisoned by Shevardnadze's government in 1993–1994, who were regarded by many Georgians and some international human rights organizations as being political prisoners. In 2013, he was posthumously awarded the title and Order of National Hero of Georgia.[34]

Gamsakhurdia's supporters continue to promote his ideas through a number of public societies. In 1996, a public, cultural and educational non-governmental organization called the Zviad Gamsakhurdia Society in the Netherlands was founded in the Dutch city of 's-Hertogenbosch. It now has members in a number of European countries.[citation needed]

Gamsakhurdia is ackhnowledged as a symbol of Georgian nationalism and Georgia's national liberation in 1990s.[35][36] For Gamsakhurdia, the state embodied the Georgian nation, while ethnic minorities were "guests".[37] He also supported Christian nationalism and viewed Georgian Orthodoxy as as the defining element of Georgian identity.[citation needed]

See also

Selected works

- 20th century American Poetry (a monograph). Ganatleba, Tbilisi, 1972 (in Georgian)

- The Man in the Panther's Skin" in English, a monograph, Metsniereba, Tbilisi, 1984, 222 pp. (In Georgian, English summary).

- "Goethe's Weltanschauung from the Anthroposophic point of view.", Tsiskari, Tbilisi, No 5, 1984 (in Georgian), link to Georgian archive version, p.149

- Tropology (Image Language) of "The Man in the Panther's Skin", monograph). Metsniereba, Tbilisi, 1991 (in Georgian)

- Collected articles and Essays. Khelovneba, Tbilisi, 1991 (in Georgian)

- Gamsakhurdia: a Product of the Soviet Union. Janice Bohle, University of Missouri, 1997.

- The Spiritual mission of Georgia (1990)

- The Spiritual Ideals of the Gelati Academy (1989) at the Wayback Machine (archived April 28, 2007)

- "Dilemma for Humanity", Nezavisimaia Gazeta, Moscow, May 21, 1992 (in Russian)

- "Between deserts" (about the creative works of L. N. Tolstoy), Literaturnaia Gazeta, Moscow, No 15, 1993 (in Russian)

- Fables and Tales. Nakaduli, Tbilisi, 1987 (in Georgian)

- The Betrothal of the Moon (Poems). Merani, Tbilisi, 1989 (in Georgian)

References

- ^ Particularly in Soviet-era sources, his patronymic is sometimes given as Konstantinovich in the Russian style.

- ^ "PM pays tribute to memory of Georgia's first President Zviad Gamsakhurdia". Agenda.ge. 31 March 2022.

- ^ Kolstø, Pål. Political Construction Sites: Nation-Building in Russia and the Post-Soviet States, p. 70. Westview Press, Boulder, Colorado, 2000.

- ^ "A Chronicle of Current Events, 30 June 1969, 8.10, "An appeal to the UN Commission on Human Rights"". Chronicle6883.wordpress.com. 28 September 2013. Retrieved 10 February 2021.

- ^ When the body was revived in the late 1980s it was renamed the Georgian Helsinki Union.

- ^ "A Chronicle of Current Events, November 1978, No 50, "Political trials in the summer of 1978"". Chronicle6883.wordpress.com. 7 April 2019. Retrieved 10 February 2021.

- ^ "A Chronicle of Current Events, 25 May 1977, 45.9, "The arrest of Zviad Gamsakhurdia and Merab Kostava"". Chronicle6883.wordpress.com. 7 April 2019. Retrieved 10 February 2021.

- ^ a b "A Chronicle of Current Events, November 1978, 50.2, "The trial of Zviad Gamsakhurdia and Merab Kostava"". Chronicle6883.wordpress.com. 18 February 2016. Retrieved 10 February 2021.

- ^ "U.S. vs. U.S.S.R.: Two on a Seesaw". Time Magazine. 10 July 1978. Archived from the original on 1 December 2008.

- ^ GEORGIA 1992: Elections and Human Rights at British Helsinki Human Rights Group website Archived November 24, 2007, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Zviad Gamsakhurdia, Open Letter to Eduard Shevardnadze". ReoCities Georgian-dedicated website. Archived from the original on 1 December 2008.

- ^ "Hastening The End of the Empire". Time Magazine. 28 January 1991. Archived from the original on 1 December 2008.

- ^ a b Bloodshed in the Caucasus: violations of humanitarian law and Human Rights in the Georgia-South Ossetia conflict (PDF). New York: Helsinki Watch, a division of Human Rights Watch. 1992. ISBN 978-1-56432-058-2.

- ^ Khutsishvili, George (February–March 1994). "Intervention in Transcaucasus". Boston University. 4 (3). Perspective.

- ^ Zakharov, Nikolay; Law, Ian (2017). Post-Soviet racisms. Mapping global racisms. London: Palgrave Macmillan. p. 118. ISBN 978-1-137-47691-3.

- ^ Sartania, Katie (27 April 2021). "Struggle and Sacrifice: Narratives of Georgia's Modern History". Carnegie Europe.

- ^ Human Rights Violations by the Government of Zviad Gamsakhurdia (Helsinki Watch via Human Rights Watch), 27 December 1991

- ^ Zviad Gamsakhurdia (1993). The Nomenklatura Revanche in Georgia. Soviet Analyst.

- ^ Russian Journal "Russki Curier", Paris, September 1991

- ^ Giga Bokeria; Givi Targamadze; Levan Ramishvili. "Nicholas Johnson: Georgia Media 1990s". University of Iowa. Archived from the original on 1 December 2008.

- ^ Tony Barber (13 December 1994). "Order at a price for Russia". The Independent. Archived from the original on 1 December 2008.

- ^ Iberia-Spektri, Tbilisi, December 15–21, 1992.

- ^ a b "ზვიად გამსახურდიას მკვლელობა - დინების საწინააღმდეგოდ". YouTube. 9 June 2013. Archived from the original on 11 December 2021. Retrieved 10 February 2021.

- ^ a b "ზვიად გამსახურდიას დაცვის წევრების ლიკვიდაციის დეტალები". YouTube. 2 April 2018. Archived from the original on 11 December 2021. Retrieved 10 February 2021.

- ^ Ken Alibek and S. Handelman. Biohazard: The Chilling True Story of the Largest Covert Biological Weapons Program in the World – Told from Inside by the Man Who Ran it. 1999. Delta (2000) ISBN 0-385-33496-6

- ^ Reburial for Georgia ex-president. The BBC News. Retrieved on April 1, 2007.

- ^ Zaza Tsuladze & Umalt Dudayev (16 February 2010). "Burial Mystery of Georgian Leader". No. 375. Archived from the original on 1 December 2008.

- ^ "Reburial for Georgia ex-president". BBC News. Archived from the original on 1 December 2008. Retrieved 1 April 2007.

- ^ "Thousands Pay Tribute to the First President". Civil Georgia. 31 March 2007. Archived from the original on 1 December 2008.

- ^ a b "First Ladies of Independent Georgia". Georgian Journal. 29 October 2018. Archived from the original on 3 November 2018. Retrieved 21 April 2020.

- ^ Elizabeth Fuller, “Geopolitics and the Gamsakhurdia Factor,” Paper delivered at AAASS Convention, Phoenix, November 19, 1992, quoted in Suny, Making of Georgian Nation, 326.

- ^ Zviad Gamsakhurdia, The Spiritual Mission of Georgia, trans. Arrian Tchanturia; ed. William Safranek (Tbilisi: Ganatleba Publishers, 1991): 7–33.

- ^ Tonoyan, Artyom (22 September 2010). "Rising Armenian-Georgian tensions and the possibility of a new ethnic conflict in the South Caucasus". Demokratizatsiya. 18 (4): 287–309.

- ^ Kirtzkhalia, N. (27 October 2013). "Georgian president awards National Hero title posthumously to Zviad Gamsakhurdia and Merab Kostava". Trend. Retrieved 14 January 2015.

- ^ "Parliament's Plenary Room to be named after Georgia's first President". Interpressnews. 9 April 2019. Retrieved 14 January 2023.

- ^ "Prime Minister's Statement". Garibashvili.ge. 31 March 2023. Retrieved 31 March 2023.

- ^ Jones, Stephen F. (1993). "Georgian- Armenian Relations in 1918-20 and 1991-94: A Comparison". Armenian Review. 46 (1–4): 57–77.

Links and literature

- President Zviad Gamsakhurdia's Memorial Page at the Wayback Machine (archived October 27, 2009)

- Reports of the International Society for Human Rights (ISHR-IGFM)

- Reports of the British Helsinki Human Rights Group (BHHRG)

- Georgian Media in the 90s: a Step To Liberty

- Country Studies: Georgia — U.S. Library of Congress

- SHAVLEGO at the Wayback Machine (archived October 27, 2009)

- [1] "The Lion in Winter — My Friend Zviad Gamsakhurdia", Todor Todorev, May 2002

- Zviad Gamsakhurdia. "Open Letter to E. Shevardnadze"

- Zviad Gamsakhurdia. "The Nomenklatura Revanche in Georgia" at the Wayback Machine (archived October 27, 2009)

- "The Transcaucasian Republics and the Coup", Elizabeth Fuller, August 1991

Media articles and references

- "Soviets Release Penitent Dissident" — The Washington Post, June 30, 1979

- "New Leaders Show Their Old Habits; Georgia, Some Other Soviet Republics Cling to Authoritarian Ways" — The Washington Post, September 18, 1991

- (in Russian) "Russki Curier", Paris, September 1991.

- (in Finnish) Aila Niinimaa-Keppo. "Shevardnadzen valhe" ("The Lie of Shevardnadze"), Helsinki, 1992.

- (in German) Johann-Michael Ginther, "About the Putch in Georgia" — Zeitgeschehen – Der Pressespiegel (Sammatz, Germany), No 14, 1992.

- "Repression Follows Putsch in Georgia!" — "Human Rights Worldwide", Frankfurt/M., No 2 (Vol. 2), 1992.

- (in Finnish) "Purges, tortures, arson, murders..." — Iltalehti (Finland), April 2, 1992.

- (in Finnish) "Entinen Neuvostoliito". Edited by Antero Leitzinger. Publishing House "Painosampo", Helsinki, 1992, pp. 114–115. ISBN 952-9752-00-8.

- "Attempted Coup Blitzed in Georgia; Two Killed" — Chicago Sun-Times, June 25, 1992.

- "Moskovskie Novosti" ("The Moscow News"), December 15, 1992.

- (in Georgian) "Iberia-Spektri", Tbilisi, December 15–21, 1992.

- J. "Soviet Analyst". Vol. 21, No: 9-10, London, 1993, pp. 15–31.

- Otto von Habsburg.- ABC (Spain). November 24, 1993.

- Robert W. Lee. "Dubious Reforms in Former USSR".- The New American, Vol. 9, No 2, 1993.

- (in English and Georgian) "Gushagi" (Journal of Georgian political émigrés), Paris, No 1/31, 1994. ISSN 0764-7247, OCLC 54453360.

- Mark Almond. "The West Underwrites Russian Imperialism" — The Wall Street Journal, European Edition, February 7, 1994.

- "Schwer verletzte Menschenrechte in Georgien" — Neue Zürcher Zeitung. August 19, 1994.

- "Intrigue Marks Alleged Death Of Georgia's Deposed Leader" — The Wall Street Journal. January 6, 1994

- "Georgians dispute reports of rebel leader's suicide" — The Guardian (UK). January 6, 1994

- "Ousted Georgia Leader a Suicide, His Wife Says" — Los Angeles Times. January 6, 1994

- "Eyewitness: Gamsakhurdia's body tells of bitter end" — The Guardian (UK). February 18, 1994.

- (in German) Konstantin Gamsachurdia: "Swiad Gamsachurdia: Dissident — Präsident — Märtyrer", Perseus-Verlag, Basel, 1995, 150 pp. ISBN 3-907564-19-7.

- Robert W. Lee. "The "Former" Soviet Bloc." — The New American, Vol. 11, No 19, 1995.

- "CAUCASUS and unholy alliance." Edited by Antero Leitzinger. ISBN 952-9752-16-4. Publishing House "Kirja-Leitzinger" (Leitzinger Books), Vantaa (Finland), 1997, 348 pp.

- (in Dutch) "GEORGIE — 1997" (Report of the Netherlands Helsinki Union/NHU), s-Hertogenbosch (The Netherlands), 1997, 64 pp.

- "Insider Report" — The New American, Vol. 13, No 4, 1997.

- Levan Urushadze. "The role of Russia in the Ethnic Conflicts in the Caucasus."- CAUCASUS: War and Peace. Edited by Mehmet Tutuncu, Haarlem (The Netherlands), 1998, 224 pp. ISBN 90-901112-5-5.

- "Insider Report" — The New American, Vol. 15, No 20, 1999.

- "Gushagi", Paris, No 2/32, 1999. OCLC 54453360.

- (in Dutch) Bas van der Plas. "GEORGIE: Traditie en tragedie in de Kaukasus." Publishing House "Papieren Tijger", Nijmegen (The Netherlands), 2000, 114 pp. ISBN 90-6728-114-X.

- (in English) Levan Urushadze. "About the history of Russian policy in the Caucasus."- IACERHRG's Yearbook — 2000, Tbilisi, 2001, pp. 64–73.

External links

Quotations related to Zviad Gamsakhurdia at Wikiquote

Quotations related to Zviad Gamsakhurdia at Wikiquote

- 1939 births

- 1993 deaths

- 20th-century male writers

- 20th-century politicians from Georgia (country)

- Anthroposophists

- Assassinated politicians from Georgia (country)

- Burials at Mtatsminda Pantheon

- Democracy activists from Georgia (country)

- Dissidents from Georgia (country)

- Eastern Orthodox Christians from Georgia (country)

- Nationalists from Georgia (country)

- Georgian independence activists

- Leaders ousted by a coup

- Members of the Georgian Orthodox Church

- Mingrelians

- National Heroes of Georgia

- Politicians from Tbilisi

- Politicians from Georgia (country) who committed suicide

- Presidents of Georgia

- Soviet dissidents

- Soviet literary historians

- Soviet male writers

- Speakers of the Parliament of Georgia

- Suicides by firearm in Georgia (country)

- Unsolved deaths

- 1990s assassinated politicians

- Assassinated presidents in Asia

- Assassinated presidents in Europe

- 20th-century assassinated national presidents

- Anti-communists from Georgia (country)