Petroleum: Difference between revisions

Orangemarlin (talk | contribs) |

|||

| Line 291: | Line 291: | ||

* Petro-cars, this is, only use petroleum and biofuels ([[biodiesel]] and [[biobutanol]]). |

* Petro-cars, this is, only use petroleum and biofuels ([[biodiesel]] and [[biobutanol]]). |

||

* [[Hybrid vehicle]]s and [[plug-in hybrid]]s, that use petroleum and other source, generally, electricity. |

* [[Hybrid vehicle]]s and [[plug-in hybrid]]s, that use petroleum and other source, generally, electricity. |

||

* Petrofree cars, that do not use petroleum, like [[electric car]]s, [[hydrogen vehicle]]s... |

* Petrofree cars, that do not use petroleum, like [[electric car]]s, [[hydrogen vehicle]]s...(although the production of hydrogen usually involves natural gas.)<ref>http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Natural_gas</ref> |

||

==Future of petroleum production== |

==Future of petroleum production== |

||

Revision as of 19:52, 9 July 2008

Petroleum (L. petroleum < Gr. πετρέλαιον lit. "rock oil" was first used in the treatise De re metallica published in 1556 by the German mineralogist Georg Bauer, known as Georgius Agricola.[1]) is a naturally occurring, flammable liquid found in rock formations in the Earth consisting of a complex mixture of hydrocarbons of various molecular weights, plus other organic compounds.

Composition

The proportion of hydrocarbons in the mixture is highly variable and ranges from as much as 97% by weight in the lighter oils to as little as 50% in the heavier oils and bitumens.

The hydrocarbons in crude oil are mostly alkanes, cycloalkanes and various aromatic hydrocarbons while the other organic compounds contain nitrogen, oxygen and sulfur, and trace amounts of metals such as iron, nickel, copper and vanadium. The exact molecular composition varies widely from formation to formation but the proportion of chemical elements vary over fairly narrow limits as follows:[2]

| Carbon | 83-87% |

| Hydrogen | 10-14% |

| Nitrogen | 0.1-2% |

| Oxygen | 0.1-1.5% |

| Sulfur | 0.5-6% |

| Metals | <1000 ppm |

Crude oil varies greatly in appearance depending on its composition. It is usually black or dark brown (although it may be yellowish or even greenish). In the reservoir it is usually found in association with natural gas, which being lighter forms a gas cap over the petroleum, and saline water, which being heavier generally floats underneath it. Crude oil may also be found in semi-solid form mixed with sand, as in the Athabasca oil sands in Canada, where it may be referred to as crude bitumen.

Petroleum is used mostly, by volume, for producing fuel oil and gasoline (petrol), both important "primary energy" sources.[3] 84% by volume of the hydrocarbons present in petroleum is converted into energy-rich fuels (petroleum-based fuels), including gasoline, diesel, jet, heating, and other fuel oils, and liquefied petroleum gas.[4]

Due to its high energy density, easy transportability and relative abundance, it has become the world's most important source of energy since the mid-1950s. Petroleum is also the raw material for many chemical products, including pharmaceuticals, solvents, fertilizers, pesticides, and plastics; the 16% not used for energy production is converted into these other materials.

Petroleum is found in porous rock formations in the upper strata of some areas of the Earth's crust. There is also petroleum in oil sands (tar sands). Known reserves of petroleum are typically estimated at around 190 km3 (1.2 trillion (short scale) barrels) without oil sands,[5] or 595 km3 (3.74 trillion barrels) with oil sands.[6] Consumption is currently around 84 million barrels (13.4×106 m3) per day, or 4.9 km3 per year. Because the energy return over energy invested (EROEI) ratio of oil is constantly falling as petroleum recovery gets more difficult, recoverable oil reserves are significantly less than total oil-in-place. At current consumption levels, and assuming that oil will be consumed only from reservoirs, known recoverable reserves would be gone around 2039, potentially leading to a global energy crisis. However, there are factors which may extend or reduce this estimate, including the rapidly increasing demand for petroleum in China, India, and other developing nations; new discoveries; energy conservation and use of alternative energy sources; and new economically viable exploitation of non-conventional oil sources.

Chemistry

Petroleum is a mixture of a very large number of different hydrocarbons; the most commonly found molecules are alkanes (linear or branched), cycloalkanes, aromatic hydrocarbons, or more complicated chemicals like asphaltenes. Each petroleum variety has a unique mix of molecules, which define its physical and chemical properties, like color and viscosity.

The alkanes, also known as paraffins, are saturated hydrocarbons with straight or branched chains which contain only carbon and hydrogen and have the general formula CnH2n+2 They generally have from 5 to 40 carbon atoms per molecule, although trace amounts of shorter or longer molecules may be present in the mixture.

The alkanes from pentane (C5H12) to octane (C8H18) are refined into gasoline (petrol), the ones from nonane (C9H20) to hexadecane (C16H34) into diesel fuel and kerosene (primary component of many types of jet fuel), and the ones from hexadecane upwards into fuel oil and lubricating oil. At the heavier end of the range, paraffin wax is an alkane with approximately 25 carbon atoms, while asphalt has 35 and up, although these are usually cracked by modern refineries into more valuable products. Any shorter hydrocarbons are considered natural gas or natural gas liquids.

The cycloalkanes, also known as napthenes, are saturated hydrocarbons which have one or more carbon rings to which hydrogen atoms are attached according to the formula CnH2n. Cycloalkanes have similar properties to alkanes but have higher boiling points.

The aromatic hydrocarbons are unsaturated hydrocarbons which have one or more planar six-carbon rings called benzene rings, to which hydrogen atoms are attached with the formula CnHn. They tend to burn with a sooty flame, and many have a sweet aroma. Some are carcinogenic.

These different molecules are separated by fractional distillation at an oil refinery to produce gasoline, jet fuel, kerosene, and other hydrocarbons. For example 2,2,4-trimethylpentane (isooctane), widely used in gasoline, has a chemical formula of C8H18 and it reacts with oxygen exothermically:[7]

The amount of various molecules in an oil sample can be determined in laboratory. The molecules are typically extracted in a solvent, then separated in a gas chromatograph, and finally determined with a suitable detector, such as a flame ionization detector or a mass spectrometer[8].

Incomplete combustion of petroleum or gasoline results in production of toxic byproducts. Too little oxygen results in carbon monoxide. Due to the high temperatures and high pressures involved, exhaust gases from gasoline combustion in car engines usually include nitrogen oxides which are responsible for creation of photochemical smog.

Formation

Geologists view crude oil and natural gas as the product of compression and heating of ancient organic materials (i.e. kerogen) over geological time. Formation of petroleum occurs from hydrocarbon pyrolysis, in a variety of mostly endothermic reactions at high temperature and/or pressure.[9] Today's oil formed from the preserved remains of prehistoric zooplankton and algae, which had settled to a sea or lake bottom in large quantities under anoxic conditions (the remains of prehistoric terrestrial plants, on the other hand, tended to form coal). Over geological time the organic matter mixed with mud, and was buried under heavy layers of sediment resulting in high levels of heat and pressure (known as diagenesis). This caused the organic matter to chemically change, first into a waxy material known as kerogen which is found in various oil shales around the world, and then with more heat into liquid and gaseous hydrocarbons in a process known as catagenesis.

Geologists often refer to the temperature range in which oil forms as an "oil window"[10]—below the minimum temperature oil remains trapped in the form of kerogen, and above the maximum temperature the oil is converted to natural gas through the process of thermal cracking. Although this temperature range is found at different depths below the surface throughout the world, a typical depth for the oil window is 4–6 km. Sometimes, oil which is formed at extreme depths may migrate and become trapped at much shallower depths where it was formed. The Athabasca Oil Sands is one example of this.

Crude oil reservoirs

Three conditions must be present for oil reservoirs to form: a source rock rich in hydrocarbon material buried deep enough for subterranean heat to cook it into oil; a porous and permeable reservoir rock for it to accumulate in; and a cap rock (seal) or other mechanism that prevents it from escaping to the surface. Within these reservoirs, fluids will typically organize themselves like a three-layer cake with a layer of water below the oil layer and a layer of gas above it, although the different layers vary in size between reservoirs.

Because most hydrocarbons are lighter than rock or water, they often migrate upward through adjacent rock layers until either reaching the surface or becoming trapped within porous rocks (known as reservoirs) by impermeable rocks above. However, the process is influenced by underground water flows, causing oil to migrate hundreds of kilometres horizontally or even short distances downward before becoming trapped in a reservoir. When hydrocarbons are concentrated in a trap, an oil field forms, from which the liquid can be extracted by drilling and pumping.

The reactions that produce oil and natural gas are often modeled as first order breakdown reactions, where hydrocarbons are broken down to oil and natural gas by a set of parallel reactions, and oil eventually breaks down to natural gas by another set of reactions. The first set was originally patented in 1694 under British Crown Patent No. 330 covering, "a way to extract and make great quantityes of pitch, tarr, and oyle out of a sort of stone."

The latter set is regularly used in petrochemical plants and oil refineries.

Non-crude reservoirs

Oil-eating bacteria biodegrades oil that has escaped to the surface. Oil sands are reservoirs of partially biodegraded oil still in the process of escaping, but contain so much migrating oil that, although most of it has escaped, vast amounts are still present—more than can be found in conventional oil reservoirs.

On the other hand, oil shales are source rocks that have not been exposed to heat or pressure long enough to convert their trapped kerogen into oil.[11]

Abiogenic origin

A number of geologists in Russia adhere to the abiogenic petroleum origin hypothesis and maintain that hydrocarbons of purely inorganic origin exist within Earth's interior. Astronomer Thomas Gold championed the theory in the Western world by supporting the work done by Nikolai Kudryavtsev in the 1950s.

The origin of petroleum has been reviewed by Kenney, Krayushkin, and Plotnikova who raise a number of objections in support of abiogenic oil.[12]

The abiogenic origin hypothesis is not utilized in exploration.[13]

Classification

The petroleum industry generally classifies crude oil by the geographic location it is produced in (e.g. West Texas, Brent, or Oman), its API gravity (an oil industry measure of density), and by its sulfur content. Crude oil may be considered light if it has low density or heavy if it has high density; and it may be referred to as sweet if it contains relatively little sulfur or sour if it contains substantial amounts of sulfur.

The geographic location is important because it affects transportation costs to the refinery. Light crude oil is more desirable than heavy oil since it produces a higher yield of gasoline, while sweet oil commands a higher price than sour oil because it has fewer environmental problems and requires less refining to meet sulfur standards imposed on fuels in consuming countries. Each crude oil has unique molecular characteristics which are understood by the use of crude oil assay analysis in petroleum laboratories.

Barrels from an area in which the crude oil's molecular characteristics have been determined and the oil has been classified are used as pricing references throughout the world. Some of the common reference crudes are:

- West Texas Intermediate (WTI), a very high-quality, sweet, light oil delivered at Cushing, Oklahoma for North American oil

- Brent Blend, comprising 15 oils from fields in the Brent and Ninian systems in the East Shetland Basin of the North Sea. The oil is landed at Sullom Voe terminal in the Shetlands. Oil production from Europe, Africa and Middle Eastern oil flowing West tends to be priced off the price of this oil, which forms a benchmark

- Dubai-Oman, used as benchmark for Middle East sour crude oil flowing to the Asia-Pacific region

- Tapis (from Malaysia, used as a reference for light Far East oil)

- Minas (from Indonesia, used as a reference for heavy Far East oil)

- The OPEC Reference Basket, a weighted average of oil blends from various OPEC (The Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries) countries

There are declining amounts of these benchmark oils being produced each year, so other oils are more commonly what is actually delivered. While the reference price may be for West Texas Intermediate delivered at Cushing, the actual oil being traded may be a discounted Canadian heavy oil delivered at Hardisty, Alberta, and for a Brent Blend delivered at the Shetlands, it may be a Russian Export Blend delivered at the port of Primorsk.[14]

Petroleum industry

The petroleum industry is involved in the global processes of exploration, extraction, refining, transporting (often with oil tankers and pipelines), and marketing petroleum products. The largest volume products of the industry are fuel oil and gasoline (petrol). Petroleum is also the raw material for many chemical products, including pharmaceuticals, solvents, fertilizers, pesticides, and plastics. The industry is usually divided into three major components: upstream, midstream and downstream. Midstream operations are usually included in the downstream category.

Petroleum is vital to many industries, and is of importance to the maintenance of industrialized civilization itself, and thus is critical concern to many nations. Oil accounts for a large percentage of the world’s energy consumption, ranging from a low of 32% for Europe and Asia, up to a high of 53% for the Middle East. Other geographic regions’ consumption patterns are as follows: South and Central America (44%), Africa (41%), and North America (40%). The world at large consumes 30 billion barrels (4.8 km³) of oil per year, and the top oil consumers largely consist of developed nations. In fact, 24% of the oil consumed in 2004 went to the United States alone.[15] The production, distribution, refining, and retailing of petroleum taken as a whole represent the single largest industry in terms of dollar value on earth.

Petroleum exploration

Extraction

The most common method of obtaining petroleum is extracting it from oil wells found in oil fields. With improved technologies and higher demand for hydrocarbons various methods are applied in petroleum exploration and development to optimize the recovery of oil and gas (Enhanced Oil Recovery, EOR). Primary recovery methods are used to extract oil that is brought to the surface by underground pressure, and can generally recover about 20% of the oil present. The natural pressure can come from several different sources; where it is provided by an underlying water layer it is called a water drive reservoir and where it is from the gas cap above it is called gas drive. After the reservoir pressure has depleted to the point that the oil is no longer brought to the surface, secondary recovery methods draw another 5 to 10% of the oil in the well to the surface. In a water drive oil field, water can be injected into the water layer below the oil, and in a gas drive field it can be injected into the gas cap above to repressurize the reservoir. Finally, when secondary oil recovery methods are no longer viable, tertiary recovery methods reduce the viscosity of the oil in order to bring more to the surface. These may involve the injection of heat, vapor, surfactants, solvents, or miscible gases as in carbon dioxide flooding.

Alternative methods

During the oil price increases since 2003, alternative methods of producing oil gained importance. The most widely known alternatives involve extracting oil from sources such as oil shale or tar sands. These resources exist in large quantities; however, extracting the oil at low cost without excessively harming the environment remains a challenge.

It is also possible to chemically transform methane or coal into the various hydrocarbons found in oil. The best-known such method is the Fischer-Tropsch process. It was a concept pioneered during the 1920s in Germany to extract oil from coal and became central to Nazi Germany's war efforts when imports of petroleum were restricted due to war. It was known as Ersatz (English:"substitute") oil, and accounted for nearly half the total oil used in WWII by Germany. However, the process was used only as a last resort as naturally occurring oil was much cheaper. As crude oil prices increase, the cost of coal to oil conversion becomes comparatively cheaper. The method involves converting high ash coal into synthetic oil in a multi-stage process.[citation needed]

Currently, two companies have commercialised their Fischer-Tropsch technology. Shell Oil in Bintulu, Malaysia, uses natural gas as a feedstock, and produces primarily low-sulfur diesel fuels.[16] Sasol[17] in South Africa uses coal as a feedstock, and produces a variety of synthetic petroleum products.

The process is today used in South Africa to produce most of the country's diesel fuel from coal by the company Sasol. The process was used in South Africa to meet its energy needs during its isolation under Apartheid. This process produces low sulfur diesel fuel but also produces large amounts of greenhouse gases.

An alternative method of converting coal into petroleum is the Karrick process, which was pioneered in the 1930s in the United States. It uses low temperatures in the absence of ambient air, to distill the short-chain hydrocarbons out of coal instead of petroleum.

Oil shale can also be used to produce oil, either through mining and processing, or in more modern methods, with in-situ thermal conversion.

Conventional crude can be extracted from unconventional reservoirs, such as the Bakken Formation. The formation is about two miles (3 km) underground but only a few meters thick, stretching across hundreds of thousands of square miles. It further has very poor extraction characteristics. Recovery at Elm Coulee has involved extensive use of horizontal drilling, solvents, and proppants.

More recently explored is thermal depolymerization (TDP), a process for the reduction of complex organic materials into light crude oil. Using pressure and heat, long chain polymers of hydrogen, oxygen, and carbon decompose into short-chain hydrocarbons. This mimics the natural geological processes thought to be involved in the production of fossil fuels. In theory, thermal depolymerization can convert any organic waste into petroleum substitutes.

History

Petroleum, in some form or other, is not a substance new in the world's history. More than four thousand years ago, according to Herodotus and confirmed by Diodorus Siculus, asphalt was employed in the construction of the walls and towers of Babylon; there were oil pits near Ardericca (near Babylon), and a pitch spring on Zacynthus.[18] Great quantities of it were found on the banks of the river Issus, one of the tributaries of the Euphrates. Ancient Persian tablets indicate the medicinal and lighting uses of petroleum in the upper levels of their society.

Oil was exploited in the Roman province of Dacia, now in Romania, where it was called picula. The earliest known oil wells were drilled in China in 347 CE or earlier. They had depths of up to about 800 feet (240 m) and were drilled using bits attached to bamboo poles.[19] The oil was burned to evaporate brine and produce salt. By the 10th century, extensive bamboo pipelines connected oil wells with salt springs. The ancient records of China and Japan are said to contain many allusions to the use of natural gas for lighting and heating. Petroleum was known as burning water in Japan in the 7th century.[18] In his book Dream Pool Essays written at 1088 AD, the polymathic scientist and statesman Shen Kuo of the Song Dynasty used a 2-character Chinese word Shi2 You2, literally Rock Oil, to name the petroleum, and this word is still being used now in contemporary Chinese.

The Middle East's petroleum industry was established by the 8th century, when the streets of the newly constructed Baghdad were paved with tar, derived from petroleum that became accessible from natural fields in the region. In the 9th century, oil fields were exploited in the area around modern Baku, Azerbaijan, to produce naphtha. These fields were described by the Arab geographer Abu al-Hasan 'Alī al-Mas'ūdī in the 10th century, and by Marco Polo in the 13th century, who described the output of those wells as hundreds of shiploads. Petroleum was distilled by the Persian alchemist Muhammad ibn Zakarīya Rāzi (Rhazes) in the 9th century, producing chemicals such as kerosene in the alembic (al-ambiq),[20] and which was mainly used for kerosene lamps.[21] Arab and Persian chemists also distilled crude oil in order to produce flammable products for military purposes. Through Islamic Spain, distillation became available in Western Europe by the 12th century.[22] It has also been present in Romania since the 13th century, being recorded as păcură.[23]

The earliest mention of American petroleum occurs in Sir Walter Raleigh's account of the Trinidad Pitch Lake in 1595; whilst thirty-seven years later, the account of a visit of a Franciscan, Joseph de la Roche d'Allion, to the oil springs of New York was published in Sagard's Histoire du Canada. A Russian traveller, Peter Kalm, in his work on America published in 1748 showed on a map the oil springs of Pennsylvania.[18]

In 1710 or 1711 (sources vary) the Russian-born Swiss physician and Greek teacher Eyrini d’Eyrinis (also spelled as Eirini d'Eirinis) discovered asphaltum at Val-de-Travers, (Neuchâtel). He established a bitumen mine de la Presta there in 1719 that operated until 1986.[24][25][26][27]

Oil sands were mined from 1745 in Merkwiller-Pechelbronn, Alsace under the direction of Louis Pierre Ancillon de la Sablonnière, by special appointment of Louis XV.[28] The Pechelbronn oil field was active until 1970, and was the birth place of companies like Antar and Schlumberger. The first modern refinery was built there in 1857.[28]

The modern history of petroleum began in 1846 with the discovery of the process of refining kerosene from coal by Nova Scotian Abraham Pineo Gesner. Ignacy Łukasiewicz improved Gesner's method to develop a means of refining kerosene from the more readily available "rock oil" ("petr-oleum") seeps in 1852 and the first rock oil mine was built in Bóbrka, near Krosno in Galicia in the following year. In 1854, Benjamin Silliman, a science professor at Yale University in New Haven, was the first to fractionate petroleum by distillation. These discoveries rapidly spread around the world, and Meerzoeff built the first Russian refinery in the mature oil fields at Baku in 1861. At that time Baku produced about 90% of the world's oil.

The first commercial oil well drilled in Romania in 1857 at Bend, North of Bucharest. The first oil well in North America was in Oil Springs, Ontario, Canada in 1858, dug by James Miller Williams. The US petroleum industry began with Edwin Drake's drilling of a 69-foot (21 m) oil well in 1859, on Oil Creek near Titusville, Pennsylvania, for the Seneca Oil Company (originally yielding 25 barrels per day (4.0 m3/d), by the end of the year output was at the rate of 15 barrels per day (2.4 m3/d)). The industry grew through the 1800s, driven by the demand for kerosene and oil lamps. It became a major national concern in the early part of the 20th century; the introduction of the internal combustion engine provided a demand that has largely sustained the industry to this day. Early "local" finds like those in Pennsylvania and Ontario were quickly outpaced by demand, leading to "oil booms" in Texas, Oklahoma, and California.

Early production of crude petroleum in the United States:[18]

- 1859: 2,000 barrels (~270 t)

- 1869: 4,215,000 barrels (~5.750×105 t)

- 1879: 19,914,146 barrels (~2.717×106 t)

- 1889: 35,163,513 barrels (~4.797×106 t)

- 1899: 57,084,428 barrels (~7.788×106 t)

- 1906: 126,493,936 barrels (~1.726×107 t)

By 1910, significant oil fields had been discovered in Canada (specifically, in the province of Ontario), the Dutch East Indies (1885, in Sumatra), Iran (1908, in Masjed Soleiman), Peru, Venezuela, and Mexico, and were being developed at an industrial level.

Even until the mid-1950s, coal was still the world's foremost fuel, but oil quickly took over. Following the 1973 energy crisis and the 1979 energy crisis, there was significant media coverage of oil supply levels. This brought to light the concern that oil is a limited resource that will eventually run out, at least as an economically viable energy source. At the time, the most common and popular predictions were quite dire. However, a period of increase production and reduced demand caused an oil glut in the 1980s.

Today, about 90% of vehicular fuel needs are met by oil. Petroleum also makes up 40% of total energy consumption in the United States, but is responsible for only 2% of electricity generation. Petroleum's worth as a portable, dense energy source powering the vast majority of vehicles and as the base of many industrial chemicals makes it one of the world's most important commodities. Access to it was a major factor in several military conflicts of the late twentieth and early twenty-first centuries, including World War II[29] and the Persian Gulf Wars (Iran-Iraq War, Operation Desert Storm, and the Iraq War)[30]. The top three oil producing countries are Saudi Arabia, Russia, and the United States.[31] About 80% of the world's readily accessible reserves are located in the Middle East, with 62.5% coming from the Arab 5: Saudi Arabia (12.5%), UAE, Iraq, Qatar and Kuwait. However, with today's oil prices, Venezuela has larger reserves than Saudi Arabia due to crude reserves derived from bitumen.

Uses

The chemical structure of petroleum is composed of hydrocarbon chains of different lengths. Because of this, petroleum may be taken to oil refineries and the hydrocarbon chemicals separated by distillation and treated by other chemical processes, to be used for a variety of purposes. See Petroleum products.

Fuels

- Ethane and other short-chain alkanes which are used as fuel

- Diesel fuel (petrodiesel)

- Fuel oils

- Gasoline

- Jet fuel

- Kerosene

- Liquid petroleum gas (LPG)

- Natural gas

Generally used in transportation, power plants and heating.

Petroleum vehicles are internal combustion engine vehicles.

Other derivatives

Certain types of resultant hydrocarbons may be mixed with other non-hydrocarbons, to create other end products:

- Alkenes (olefins) which can be manufactured into plastics or other compounds

- Lubricants (produces light machine oils, motor oils, and greases, adding viscosity stabilizers as required).

- Wax, used in the packaging of frozen foods, among others.

- Sulfur or Sulfuric acid. These are a useful industrial materials. Sulfuric acid is usually prepared as the acid precursor oleum, a byproduct of sulfur removal from fuels.

- Bulk tar.

- Asphalt

- Petroleum coke, used in speciality carbon products or as solid fuel.

- Paraffin wax

- Aromatic petrochemicals to be used as precursors in other chemical production.

Consumption statistics

-

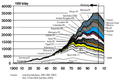

2004 U.S. government predictions for oil production other than in OPEC and the former Soviet Union

-

World energy consumption, 1980-2030. Source: International Energy Outlook 2006.

Environmental effects

The presence of oil has significant social and environmental impacts, from accidents and routine activities such as seismic exploration, drilling, and generation of polluting wastes not produced by other alternative energies.

Extraction

Oil extraction is costly and sometimes environmentally damaging, although Dr. John Hunt of the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution pointed out in a 1981 paper that over 70% of the reserves in the world are associated with visible macroseepages, and many oil fields are found due to natural seeps. Offshore exploration and extraction of oil disturbs the surrounding marine environment.[32] Extraction may involve dredging, which stirs up the seabed, killing the sea plants that marine creatures need to survive. But at the same time, offshore oil platforms also form micro-habitats for marine creatures.

Oil spills

Crude oil and refined fuel spills from tanker ship accidents have damaged natural ecosystems in Alaska, the Galapagos Islands, France and many other places.

The quantity of oil spilled during accidents has ranged from a few hundred tons to several hundred thousand tons (Atlantic Empress, Amoco Cadiz...). Smaller spills have already proven to have a great impact on ecosystems, such as the Exxon Valdez oil spill

Oil spills at sea are generally much more damaging than those on land, since they can spread for hundreds of nautical miles in a thin oil slick which can cover beaches with a thin coating of oil. This can kill sea birds, mammals, shellfish and other organisms it coats. Oil spills on land are more readily containable if a makeshift earth dam can be rapidly bulldozed around the spill site before most of the oil escapes, and land animals can avoid the oil more easily.

Control of oil spills is difficult, requires ad hoc methods, and often a large amount of manpower (picture). The dropping of bombs and incendiary devices from aircraft on the Torrey Canyon wreck got poor results;[33] modern techniques would include pumping the oil from the wreck, like in the Prestige oil spill or the Erika oil spill.[34]

Global warming

Burning oil releases carbon dioxide (CO2) into the atmosphere, which is credited with contributing to global warming. Per joule, oil produces 15% less CO2 than coal, but 30% more than natural gas[citation needed]. However, the unique role of oil as the main source of transportation fuel makes reducing its CO2 emissions a difficult problem. While large power plants can, in theory, eliminate their CO2 emissions by techniques such as carbon sequestering or even use them to increase oil production through enhanced oil recovery techniques, these amelioration strategies do not generally work for individual vehicles

Whales

It has been argued that the advent of petroleum-refined kerosene saved the great cetaceans from extinction by providing a cheap substitute for whale oil, thus eliminating the economic imperative for whaling.[35]

Alternatives to petroleum

Alternatives to petroleum-based vehicle fuels

The term alternative propulsion or "alternative methods of propulsion" includes both:

- alternative fuels used in standard or modified internal combustion engines (i.e. combustion hydrogen or biofuels).

- propulsion systems not based on internal combustion, such as those based on electricity (for example, all-electric or hybrid vehicles), compressed air, or fuel cells (i.e. hydrogen fuel cells).

Nowadays, cars can be classified between the next main groups:

- Petro-cars, this is, only use petroleum and biofuels (biodiesel and biobutanol).

- Hybrid vehicles and plug-in hybrids, that use petroleum and other source, generally, electricity.

- Petrofree cars, that do not use petroleum, like electric cars, hydrogen vehicles...(although the production of hydrogen usually involves natural gas.)[36]

Future of petroleum production

The future of petroleum as a fuel remains somewhat controversial. USA Today news reported in 2004 that there were 40 years of petroleum left in the ground. Some argue that because the total amount of petroleum is finite, the dire predictions of the 1970s have merely been postponed. Others claim that technology will continue to allow for the production of cheap hydrocarbons and that the earth has vast sources of unconventional petroleum reserves in the form of tar sands, bitumen fields and oil shale that will allow for petroleum use to continue in the future, with both the Canadian tar sands and United States shale oil deposits representing potential reserves matching existing liquid petroleum deposits worldwide.[11]

Hubbert peak theory

The Hubbert peak theory (also known as peak oil) posits that future petroleum production (whether for individual oil wells, entire oil fields, whole countries, or worldwide production) will eventually peak and then decline at a similar rate to the rate of increase before the peak as these reserves are exhausted. It also suggests a method to calculate the timing of this peak, based on past production rates, the observed peak of past discovery rates, and proven oil reserves. The peak of oil discoveries was in 1965, and oil production per year has surpassed oil discoveries every year since 1980.[37]

In 1956, M. King Hubbert correctly predicted US oil production would peak around 1971. When this occurred and the US began losing its excess production capacity, OPEC gained the ability to manipulate oil prices, leading to the 1973 and 1979 oil crises. Since then, most other countries have also peaked. China has confirmed that two of its largest producing regions are in decline, and Mexico's national oil company, Pemex, has announced that Cantarell Field, one of the world's largest offshore fields, was expected to peak in 2006, and then decline 14% per annum.

Controversy surrounds predictions of the timing of the global peak, as these predictions are dependent on the past production and discovery data used in the calculation as well as how unconventional reserves are considered. Supergiant fields have been discovered in the past decade, such as Azadegan, Carioca/Sugar Loaf, Tupi, Jupiter, Ferdows/Mounds/Zagheh, Tahe, Jidong Nanpu/Bohai Bay, West Kamchatka, and Kashagan, as well as tremendous reservoir growth from places like the Bakken and massive syncrude operations in Venezuela and Canada.[38] However, while past understanding of total oil reserves changed with newer scientific understanding of petroleum geology, current estimates of total oil reserves have been in general agreement since the 1960s. Further, predictions regarding the timing of the peak are highly dependent on the past production and discovery data used in the calculation.

It is difficult to predict the oil peak in any given region, due to the lack of transparency in accounting of global oil reserves.[39] Based on available production data, proponents have previously predicted the peak for the world to be in years 1989, 1995, or 1995-2000. Some of these predictions date from before the recession of the early 1980s, and the consequent reduction in global consumption, the effect of which was to delay the date of any peak by several years. Just as the 1971 U.S. peak in oil production was only clearly recognized after the fact, a peak in world production will be difficult to discern until production clearly drops off.

Petroleum by country

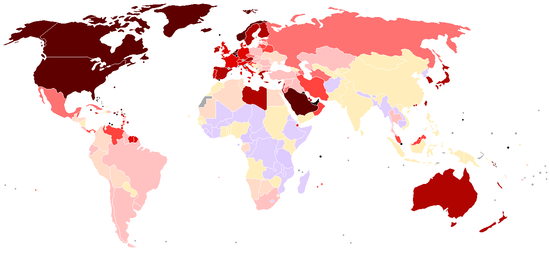

Consumption rates

There are two main ways to measure the oil consumption rates of countries: by population or by gross domestic product (GDP). This metric is important in the global debate over oil consumption/energy consumption/climate change because it takes social and economic considerations into account when scoring countries on their oil consumption/energy consumption/climate change goals. Nations such as China and India with large populations tend to promote the use of population based metrics, while nations with large economies such as the United States would tend to promote the GDP based metric.[citation needed]

|

(Note: The figure for Singapore is skewed because of its small |

Production

In petroleum industry parlance, production refers to the quantity of crude extracted from reserves, not the literal creation of the product.

| # | Producing Nation | 103bbl/d (2006) | 103bbl/d (2007) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Saudi Arabia (OPEC) | 10,665 | 10,234 |

| 2 | Russia 1 | 9,677 | 9,876 |

| 3 | United States 1 | 8,331 | 8,481 |

| 4 | Iran (OPEC) | 4,148 | 4,043 |

| 5 | China | 3,845 | 3,901 |

| 6 | Mexico 1 | 3,707 | 3,501 |

| 7 | Canada 2 | 3,288 | 3,358 |

| 8 | United Arab Emirates (OPEC) | 2,945 | 2,948 |

| 9 | Venezuela (OPEC) 1 | 2,803 | 2,667 |

| 10 | Kuwait (OPEC) | 2,675 | 2,613 |

| 11 | Norway 1 | 2,786 | 2,565 |

| 12 | Nigeria (OPEC) | 2,443 | 2,352 |

| 13 | Brazil | 2,166 | 2,279 |

| 14 | Algeria (OPEC) | 2,122 | 2,173 |

| 15 | Iraq (OPEC) 3 | 2,008 | 2,094 |

| 16 | Libya (OPEC) | 1,809 | 1,845 |

| 17 | Angola (OPEC) | 1,435 | 1,769 |

| 18 | United Kingdom | 1,689 | 1,690 |

| 19 | Kazakhstan | 1,388 | 1,445 |

| 20 | Qatar (OPEC) | 1,141 | 1,136 |

| 21 | Indonesia | 1,102 | 1,044 |

| 22 | India | 854 | 881 |

| 23 | Azerbaijan | 648 | 850 |

| 24 | Argentina | 802 | 791 |

| 25 | Oman | 743 | 714 |

| 26 | Malaysia | 729 | 703 |

| 27 | Egypt | 667 | 664 |

| 28 | Australia | 552 | 595 |

| 29 | Colombia | 544 | 543 |

| 30 | Ecuador (OPEC) | 536 | 512 |

| 31 | Sudan | 380 | 466 |

| 32 | Syria | 449 | 446 |

| 33 | Equatorial Guinea | 386 | 400 |

| 34 | Yemen | 377 | 361 |

| 35 | Vietnam | 362 | 352 |

| 36 | Thailand | 334 | 349 |

| 37 | Denmark | 344 | 314 |

| 38 | Congo | 247 | 250 |

| 39 | Gabon | 237 | 244 |

| 40 | South Africa | 204 | 199 |

Source: U.S. Energy Information Administration

1 peak production of conventional oil already passed in this state

2 Although Canadian conventional oil production is declining, total oil production is increasing as oil sands production grows. If oil sands are included, it has the world's second largest oil reserves after Saudi Arabia.

3 Though still a member, Iraq has not been included in production figures since 1998

Export

In order of net exports in 2006 in thousand bbl/d and thousand m³/d:

| # | Exporting Nation (2006) | (103bbl/d) | (103m3/d) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Saudi Arabia (OPEC) | 8,651 | 1,376 |

| 2 | Russia 1 | 6,565 | 1,044 |

| 3 | Norway 1 | 2,542 | 404 |

| 4 | Iran (OPEC) | 2,519 | 401 |

| 5 | United Arab Emirates (OPEC) | 2,515 | 400 |

| 6 | Venezuela (OPEC) 1 | 2,203 | 350 |

| 7 | Kuwait (OPEC) | 2,150 | 342 |

| 8 | Nigeria (OPEC) | 2,146 | 341 |

| 9 | Algeria (OPEC) 1 | 1,847 | 297 |

| 10 | Mexico 1 | 1,676 | 266 |

| 11 | Libya (OPEC) 1 | 1,525 | 242 |

| 12 | Iraq (OPEC) | 1,438 | 229 |

| 13 | Angola (OPEC) | 1,363 | 217 |

| 14 | Kazakhstan | 1,114 | 177 |

| 15 | Canada 2 | 1,071 | 170 |

Source: US Energy Information Administration

1 peak production already passed in this state

2 Canadian statistics are complicated by the fact it is both an importer and exporter of crude oil, and refines large amounts of oil for the U.S. market. It is the leading source of U.S. imports of oil and products, averaging 2.5 MMbbl/d in August 2007. [2].

Total world production/consumption (as of 2005) is approximately 84 million barrels per day (13,400,000 m3/d).

See also: Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries.

Consumption

In order of amount consumed in 2006 in thousand bbl/d and thousand m³/d:

| # | Consuming Nation 2006 | (103bbl/day) | (103m3/day) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | United States 1 | 20,588 | 3,273 |

| 2 | China | 7,274 | 1,157 |

| 3 | Japan 2 | 5,222 | 830 |

| 4 | Russia 1 | 3,103 | 493 |

| 5 | Germany 2 | 2,630 | 418 |

| 6 | India 2 | 2,534 | 403 |

| 7 | Canada | 2,218 | 353 |

| 8 | Brazil | 2,183 | 347 |

| 9 | South Korea 2 | 2,157 | 343 |

| 10 | Saudi Arabia (OPEC) | 2,068 | 329 |

| 11 | Mexico 1 | 2,030 | 323 |

| 12 | France 2 | 1,972 | 314 |

| 13 | United Kingdom 1 | 1,816 | 289 |

| 14 | Italy 2 | 1,709 | 272 |

| 15 | Iran (OPEC) | 1,627 | 259 |

Source: US Energy Information Administration

1 peak production of oil already passed in this state

2 This country is not a major oil producer

Import

In order of net imports in 2006 in thousand bbl/d and thousand m³/d:

| # | Importing Nation (2006) | (103bbl/day) | (103m3/day) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | United States 1 | 12,220 | 1,943 |

| 2 | Japan | 5,097 | 810 |

| 3 | China 2 | 3,438 | 547 |

| 4 | Germany | 2,483 | 395 |

| 5 | South Korea | 2,150 | 342 |

| 6 | France | 1,893 | 301 |

| 7 | India | 1,687 | 268 |

| 8 | Italy | 1,558 | 248 |

| 9 | Spain | 1,555 | 247 |

| 10 | Taiwan | 942 | 150 |

| 11 | Netherlands | 936 | 149 |

| 12 | Singapore | 787 | 125 |

| 13 | Thailand | 606 | 96 |

| 14 | Turkey | 576 | 92 |

| 15 | Belgium | 546 | 87 |

Source: US Energy Information Administration

1 peak production of oil already passed in this state

2 Major oil producer whose production is still increasing

Non-producing consumers

Countries whose oil production is 10% or less of their consumption.

| # | Consuming Nation | (bbl/day) | (m³/day) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Japan | 5,578,000 | 886,831 |

| 2 | Germany | 2,677,000 | 425,609 |

| 3 | South Korea | 2,061,000 | 327,673 |

| 4 | France | 2,060,000 | 327,514 |

| 5 | Italy | 1,874,000 | 297,942 |

| 6 | Spain | 1,537,000 | 244,363 |

| 7 | Netherlands | 946,700 | 150,513 |

Source : CIA World Factbook

Writers covering the petroleum industry

See also

References

- ^ Bauer Georg, Hoover Herbert (tr.), Hoover Lou(tr.). De re metallica. Vol. xii.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|originallanguage=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|originalyear=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) translated 1912 - ^ Speight, James G. (1999). The Chemistry and Technology of Petroleum. Marcel Dekker. pp. pp. 215-216. ISBN 0824702174.

{{cite book}}:|pages=has extra text (help) - ^ IEA Key World Energy Statistics

- ^ "Crude oil is made into different fuels"

- ^ EIA reserves estimates

- ^ CERA report on total world oil

- ^ Heat of Combustion of Fuels

- ^ Use of ozone depleting substances in laboratories. TemaNord 2003:516. http://www.norden.org/pub/ebook/2003-516.pdf

- ^ Petroleum Study

- ^ Oil Is Mastery

- ^ a b Lambertson, Giles (2008-02-16). "Oil Shale: Ready to Unlock the Rock". Construction Equipment Guide. Retrieved 2008-05-21.

- ^ Kenney et al., Dismissal of the Claims of a Biological Connection for Natural Petroleum, Energia 2001

- ^ Glasby, Geoffrey P. (2006). "Abiogenic origin of hydrocarbons: an historical overview" (PDF). Resource Geology. 56 (1): 83–96. Retrieved 2008-02-17.

- ^ "Light Sweet Crude Oil". About the Exchange. New York Mercantile Exchange (NYMEX). 2006. Retrieved 2008-04-21.

- ^ ""International Energy Annual 2004" (XLS). Energy Information Administration. 2006-07-14.

- ^ Shell Middle Distillate Synthesis Malaysia

- ^ Sasol corporate website

- ^ a b c d This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Petroleum". Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

- ^ ASTM timeline of oil

- ^ Dr. Kasem Ajram (1992). The Miracle of Islam Science (2nd Edition ed.). Knowledge House Publishers. ISBN 0-911119-43-4.

{{cite book}}:|edition=has extra text (help) - ^ Zayn Bilkadi (University of California, Berkeley), "The Oil Weapons", Saudi Aramco World, January-February 1995, pp. 20-7

- ^ Joseph P. Riva Jr. and Gordon I. Atwater. "petroleum". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 2008-06-30.

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ Istoria Romaniei, Vol II, p. 300, 1960

- ^ [1]

- ^ Le bitume et la mine de la Presta (Suisse), Jacques Lapaire, Mineraux et Fossiles No 315

- ^ "Asphaltum" Stoddart's Encyclopaedia Americana (1883) pages 344–345

- ^ Eirinis' paper, entitled "Dissertation sur la mine d'asphalte contenant la manière dont se doivent régler Messieurs les associés pour son exploitation, le profit du Roy, & celui de la Société, & ce qui sera dû à Mr d'Erinis à qui elle apartient 'per Ligium feudum' " is held at the BPU Neuchâtel - Fonds d'étude [Ne V] catalogue

- ^ a b History of Pechelbronn oil

- ^ Hanson Baldwin, 1959, “Oil Strategy in World War II", American Petroleum Institute Quarterly – Centennial Issue, pages 10-11. American Petroleum Institute.

- ^ Robison, R.P. (2006), The Middle East War Process: The Truth Behind America's Middle East Challenge, Authorhouse, retrieved 2008-06-18

- ^ InfoPlease

- ^ Waste discharges during the offshore oil and gas activity by Stanislave Patin, tr. Elena Cascio

- ^ Torrey Canyon bombing by the Navy and RAF

- ^ Pumping of the Erika cargo

- ^ How Capitalism Saved the Whales by James S. Robbins, The Freeman, August, 1992.

- ^ http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Natural_gas

- ^

Campbell CJ (2000-12). "Peak Oil] Presentation at the Technical University of Clausthal".

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ NCPA - Policy Backgrounder 159 - Are We Running Out of Oil?

- ^ New study raises doubts about Saudi oil reserves

External links

- Template:Dmoz

- US Energy Information Administration

- US Department of Energy EIA - World supply and consumption

- American Petroleum Institute - the trade association of the US oil industry.

- Oil survey - OECD International Energy Agency