Hungarian language: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 520: | Line 520: | ||

=====Hungarian names in foreign languages===== |

=====Hungarian names in foreign languages===== |

||

For clarity, in foreign languages Hungarian names are usually represented in the western name order. Sometimes, however, especially in the neighboring countries of Hungary – where there is a |

For clarity, in foreign languages Hungarian names are usually represented in the western name order. Sometimes, however, especially in the neighboring countries of Hungary – where there is a [[Treaty of Trianon|significant Hungarian population]] – the Hungarian name order is retained as it causes less confusion there. |

||

For an example of foreign use, the birth name of the Hungarian-born physicist, the "father of the [[hydrogen bomb]]" was '''''Teller Ede''''', but he became known internationally as '''''[[Edward Teller]]'''''. Prior to the mid-20th century, given names were usually translated along with the name order; this is no longer as common. For example, the pianist uses ''[[András Schiff]]'' when abroad, not ''Andrew Schiff'' (in Hungarian ''Schiff András''). A second given name, if present, becomes a middle name, but is usually written out in full, and not truncated to an initial. |

For an example of foreign use, the birth name of the Hungarian-born physicist, the "father of the [[hydrogen bomb]]" was '''''Teller Ede''''', but he became known internationally as '''''[[Edward Teller]]'''''. Prior to the mid-20th century, given names were usually translated along with the name order; this is no longer as common. For example, the pianist uses ''[[András Schiff]]'' when abroad, not ''Andrew Schiff'' (in Hungarian ''Schiff András''). A second given name, if present, becomes a middle name, but is usually written out in full, and not truncated to an initial. |

||

Revision as of 17:18, 13 March 2010

| Hungarian | |

|---|---|

| Magyar | |

| Pronunciation | [ˈmɒɟɒr̪] |

| Native to | Hungary and areas of Romania, Serbia, Slovakia, Slovenia, Ukraine, Croatia, Austria, and Israel |

Native speakers | 13 million |

Uralic

| |

| Latin alphabet (Hungarian variant) | |

| Official status | |

Official language in | Hungary, European Union, Slovakia (regional language), Slovenia (regional language), Serbia (regional language), Austria (regional language), Various localities in Romania, Some official rights in Ukraine and Croatia |

| Regulated by | Research Institute for Linguistics of the Hungarian Academy of Sciences |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-1 | hu |

| ISO 639-2 | hun |

| ISO 639-3 | hun |

| Hungarian language |

|---|

|

| Alphabet |

| Grammar |

| History |

|

|

| Other features |

| Hungarian and English |

Hungarian (magyar nyelv ) is a Uralic language, more specifically a Finno-Ugric language related to Finnish, Estonian and a number of other minority languages spoken in the Baltic states and northern European Russia eastward into central Siberia. Finno-Ugric languages are not related to the Indo-european languages that dominate Europe but have acquired loan words from them.

Hungarian is mainly spoken in Hungary and by the Hungarian communities in the seven neighbouring countries. The Hungarian name for the language is magyar (Hungarian pronunciation: [ˈmɒɟɒr̪]), which is also occasionally used as an English noun, such as Mighty Magyars. There are about 14.5 million native speakers, of whom 9.5–10 million live in present-day Hungary. About 2.5 million speakers live outside present-day Hungary, but in areas that were part of the Kingdom of Hungary before the Treaty of Trianon (1920). Of these, the largest group lives in Romania, where there are approximately 1.4 million Hungarians. There are large, majority Hungarian territories also in Slovakia, Serbia and Ukraine, but Hungarian speakers can also be found in Croatia, Austria, and Slovenia, as well as about a million people scattered in other parts of the world, for example the more than a hundred thousand Hungarian speakers in the Hungarian American community in the United States.

History

Classification

Hungarian is a Uralic language, more specifically a Ugric language; the most closely related languages are Mansi and Khanty of western Siberia. Connections between the Ugric and Finnic languages were noticed in the 1670s and established, along with the entire Uralic family in 1717, although the classification of Hungarian continued to be a matter of political controversy into the 18th and even 19th centuries. Today the Uralic family is considered one of the best demonstrated large language families, along with Indo-European and Austronesian[citation needed]. The name of Hungary could be a corruption of Ungrian/Ugrian, and the fact that the Eastern Slavs referred to them as Ǫgry/Ǫgrove (sg. Ǫgrinŭ) seemed to confirm that.[1] As to the source of this ethnonym in the Slavic languages, current literature favors the hypothesis that it comes from the name of the Turkic tribe Onogur (which means "ten arrows" or "ten tribes").[2][3][4]

There are numerous regular sound correspondences between Hungarian and the other Ugric languages. For example, Hungarian /aː/ corresponds to Khanty /o/ in certain positions, and Hungarian /h/ corresponds to Khanty /x/, while Hungarian final /z/ corresponds to Khanty final /t/. For example, Hungarian ház ([haːz]) "house" vs. Khanty xot ([xot]) "house", and Hungarian száz ([saːz]) "hundred" vs. Khanty sot ([sot]) "hundred".

The distance between the Ugric and Finnic languages is greater, but the correspondences are also regular.

Antiquity and the early Middle Ages

As Uralic linguists claim[who?], Hungarian separated from its closest relatives approximately 3000 years ago, so the history of the language begins around 1000 BC. The Hungarians gradually changed their way of living from settled hunters to nomadic cattle-raising, probably as a result of early contacts with Iranian nomads. Their most important animals included sheep and cattle. There are no written resources on the era, thus only a little is known about it. However, research has revealed some extremely early loanwords, such as szó ('word'; from the Turkic languages) and daru ('crane', from the related Permic languages.)

Hungarian historian and archaeologist, Gyula László refutes this theory, however, citing geological data as evidence, stating, "This seemed to be an impeccable conclusion until attention was paid to the actual testimony of tree-pollen analyses, and these showed that the linguists had failed to take into account changes in the vegetation zones over the millennia. After analysis of the plant pollens in the supposed homeland of the Magyars, which were preserved in the soil, it became clear to scientists that the taiga and deciduous forests were only in contact during the second millennium B.C., which is much too late to have an impact on Finno-Ugrian history. So the territory sought by the linguists as the location of the putative ‘ancient homeland’ never existed. At 5,000-6,000B.C., the period at which the Uralic era has been dated, the taiga was still thousands of kilometers away from the Ural mountains and the mixed deciduous forest had only just begun its northward advance."[5] This geological data contradicts earlier claims by linguists about the ancient homeland of the Magyars near the Urals.

The Turkic languages later, especially between the 5th and the 9th centuries, had a great influence on the language. Most words related to agriculture,[6] to state administration or even to family relations have such backgrounds. Interestingly, Hungarian syntax and grammar was not influenced in a similarly dramatic way during this 300 years.

The Hungarians migrated to the Carpathian Basin around 896 and came into contact with Slavic peoples – as well as with the Romance speaking Vlachs, borrowing many words from them (for example tégla – "brick", mák – "poppy", or karácsony – "Christmas"). In exchange, the neighbouring Slavic languages also contain some words of Hungarian origin (such as Croatian čizma (csizma) – "boot", or Serbian ašov (ásó) – "spade"). 1,43% of the Romanian vocabulary is of Hungarian origin.[7]

The first written accounts of Hungarian, mostly personal and place names, are dated back to the 10th century. Hungarians also had their own writing system, the Old Hungarian script, but no significant texts remained from the time due to, as researchers say, Stephen I of Hungary, who gave an order to burn the written sticks.

Since the foundation of the Kingdom of Hungary

The Kingdom of Hungary was founded in 1000, by Stephen I of Hungary (Hungarian: I. (Szent) István király). The country was a western-styled Christian (Roman Catholic) state, and Latin held an important position, as was usual in the Middle Ages. Additionally, the Latin alphabet was adopted to write the Hungarian language.

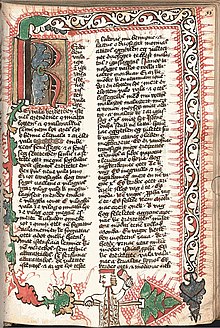

Therefore, Hungarian was also heavily influenced by Latin. The first extant text of the language is the Funeral Sermon and Prayer, written once in the 1190s. More extensive Hungarian literature arose after 1300. The earliest example of Hungarian religious poetry is the Old Hungarian 'Lamentations of Mary', a poem about the afflictions of Mary when she saw the death of her son - from the 14th century. The first Bible translation is the Hussite Bible from the 1430s.

The language lost its diphthongs, and several postpositions transformed into suffixes, such as reá 'onto'– 1055: utu rea 'onto the way'; later: útra). Vowel harmony was also developed. At one time, Hungarian used six verb tenses; today, only two (the future not being counted as one, as it is formed with an auxiliary verb).

The first printed Hungarian book was published in Kraków in 1533, by Benedek Komjáti. The work's title is Az Szent Pál levelei magyar nyelven (In original spelling: Az zenth Paal leueley magyar nyeluen), i.e. The letters of Saint Paul in the Hungarian language. In the 17th century, the language was already very similar to its present-day form, although two of the past tenses were still used. German, Italian and French loans also appeared in the language by these years. Further Turkish words were borrowed during the Ottoman occupation of much of Hungary between 1541 and 1699.

In the 18th century, the language was incapable of clearly expressing scientific concepts, and several writers found the vocabulary a bit scant for literary purposes. Thus, a group of writers, most notably Ferenc Kazinczy, began to compensate for these imperfections. Some words were shortened (győzedelem > győzelem, 'triumph' or 'victory'); a number of dialectal words spread nationally (e. g. cselleng 'dawdle'); extinct words were reintroduced (dísz 'décor'); a wide range of expressions were coined using the various derivative suffixes; and some other, less frequently used methods of expanding the language were utilized. This movement was called the 'language reform' (Hungarian: nyelvújítás), and produced more than ten thousand words, many of which are used actively today. The reforms led[citation needed] to the installment of Hungarian as the official language over Latin in the multiethnic country in 1844.

The 19th and 20th centuries saw further standardization of the language, and differences between the mutually already comprehensible dialects gradually lessened. In 1920, by signing the Treaty of Trianon, Hungary lost 71% of its territories, and along with these, 33% of the ethnic Hungarian population. Today, the language is official in Hungary, and regionally also in Romania, in Slovakia, and in Serbia.

Geographic distribution

Hungarian is spoken in the following countries as a mother tongue:

| Country | Speakers |

|---|---|

| Hungary | 10,177,223 (2001 census) |

| Romania (mainly Transylvania) |

1,443,970 (census 2002) |

| Slovakia | 520,528 (census 2001) |

| Serbia (mainly Vojvodina) |

293,299 (census 2002) |

| Ukraine (mainly Zakarpattia) |

149,400 (census 2001) |

| United States | 117,973 (census 2000) |

| Canada | 75,555 (census 2001) |

| Israel | 70,000 |

| Austria (mainly Burgenland) |

22,000 |

| Croatia | 16,500 |

| Slovenia (mainly Prekmurje) |

9,240 |

| Total | 12-13 million (in Carpathian Basin) |

- Source: National censuses, Ethnologue

About a million more Hungarian speakers live in Argentina, Australia, Belgium, Brazil, the Czech Republic, Finland, France, Germany, the Netherlands, Italy, Switzerland, the United Kingdom, the United States, Venezuela and in other parts of the world.

Official status

Hungarian is the official language of Hungary, and thus an official language of the European Union. Hungarian is also one of the official languages of Vojvodina and an official language of three municipalities in Slovenia: Hodoš, Dobrovnik and Lendava, along with Slovene. Hungarian is officially recognized as a minority or regional language in Austria, Croatia, Romania, Bukovina, Zakarpattia in Ukraine, and Slovakia. In Romania it is an official language at local level in all communes, towns and municipalities with an ethnic Hungarian population of over 20%.

Dialects

The dialects of Hungarian identified by Ethnologue are: Alföld, West Danube, Danube-Tisza, King's Pass Hungarian, Northeast Hungarian, Northwest Hungarian, Székely and West Hungarian. These dialects are, for the most part, mutually intelligible. The Hungarian Csángó dialect, which is not listed by Ethnologue, is spoken mostly in Bacău County, Romania. The Csángó minority group has been largely isolated from other Hungarian people, and they therefore preserved a dialect closely resembling medieval Hungarian.

Phonology

Hungarian has 14 vowel phonemes and 25 consonant phonemes. The vowel phonemes can be grouped as pairs of long and short vowels, e.g. o and ó. Most of these pairs have a similar pronunciation, only varying significantly in their duration. However, the pairs <a>/<á> and <e>/<é> differ both in closedness and length.

| Bilabial | Labio- dental |

Alveolar | Post- alveolar |

Palatal | Velar | Glottal | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nasal | m | n | ɲ | ||||

| Plosive | p b | t d | k ɡ | ||||

| Affricate | t͡s d͡z | t͡ʃ d͡ʒ | c͡ç ɟ͡ʝ | ||||

| Fricative | f v | s z | ʃ ʒ | h | |||

| Trill | r | ||||||

| Approximant | j | ||||||

| Lateral | l |

Consonant length is also distinctive in Hungarian. Most of the consonant phonemes can occur as geminates.

The sound voiced palatal plosive /ɟ/, written <gy>, sounds similar to 'd' in British English 'duty' (in fact, more similar to 'd' in French 'dieu', or to the Macedonian phoneme 'ѓ' as in 'ѓакон'). It occurs in the name of the country, "Magyarország" (Hungary), pronounced /ˈmɒɟɒrorsaːɡ/.

Primary stress is always on the first syllable of a word, as with its cousin Finnish and neighboring languages, Slovak (Standard dialect) and Czech. There is sometimes secondary stress on other syllables, especially in compounds, e.g. viszontlátásra ("goodbye") pronounced /ˈvisontˌlaːtaːʃrɒ/. Elongated vowels in non-initial syllables can also seem to be stressed to the ear of an English speaker, since length and stress correlate in English.

Front-back vowel harmony is an important feature of Hungarian phonology.

Single /r/s are tapped, like the Spanish pero; double /r/s are trilled, like the Spanish perro.

Grammar and syntax

Hungarian is an agglutinative language – it uses a number of different affixes, including suffixes, prefixes and a circumfix to define the meaning or the grammatical function. Instead of prepositions, which are common in English, Hungarian uses only postpositions.

There are two types of article in Hungarian:

- definite: a before words beginning with consonants and az before vowels (in a phonological sense, behaving just like the indefinite article ’a(n)’ in English)

- indefinite: egy, literally ‘one’.

Nouns have as many as eighteen cases. Of these, some are grammatical, e.g. the unmarked nominative (for example, az alma ‘the apple’), and the accusative marked with the suffix –t (az almát). The latter is used when the noun in question is used as the object of a verb. Hungarian does not have a genitive case (the dative case is used instead), and numerous English prepositions are equivalent not to an affix, but to a postposition, as in az alma mellett ‘next to the apple’. Plurals are formed using the suffix –k (az almák ‘the apples’).

Adjectives precede nouns, e. g. a piros alma ‘the red apple’. They have three degrees, including base (piros ‘red’), comparative (pirosabb ‘redder’), and superlative (legpirosabb ‘reddest’). If the noun takes the plural or a case, the adjective, used attributively, does not agree with it: a piros almák ‘the red apples’. However, when the adjective is used in a predicative sense, it must agree with the noun: az almák pirosak ‘the apples are red’. Adjectives also take cases when they are used without nouns: Melyik almát kéred? - A pirosat. 'Which apple would you like? - The red one.'

Verbs developed a complex conjugation system during the centuries. Every Hungarian verb has two conjugations (definite and indefinite), two tenses (past and present-future), and three moods (indicative, conditional and imperative), two numbers (singular or plural), and three persons (first, second and third). Out of these features, the two different conjugations are the most characteristic: the "definite" conjugation is used for a transitive verb with a definite object. The "indefinite" conjugation is used for an intransitive verb or for a transitive verb with an indefinite object. These rules, however, do not apply everywhere. The following examples demonstrate this system:

| John lát. ‘John can see.’ (indefinite: he has the ability of vision) |

John lát egy almát. ‘John sees an apple.’ (indefinite: it does not matter which apple) |

John látja az almát. ‘John sees the apple.’ (definite: John sees the specific apple that was talked about earlier) |

Present tense is unmarked, while past is formed using the suffix –t or sometimes –tt: lát 'sees'; látott 'saw', past. Futurity is often expressed with the present tense, or using the auxiliary verb fog ‘will’. The first most commonly applies when the sentence also defines the time of the future event, for example John pénteken moziba megy – literally ‘John on Friday into cinema goes’, i.e. ‘On Friday, John will go to the cinema.’ In the other case, the verb’s infinitive (formed using –ni) and the ‘fog’ auxiliary verb is used: John moziba fog menni – ‘John will go to the cinema.’ This is sometimes counted as a tense, especially by non-specialist publications.

Indicative mood is used in all tenses; the conditional only in the present and the past, finally the imperative just in the present. Indicative is always unmarked. Verbs also have verbal prefixes. Most of them define movement direction (lemegy – goes down, felmegy – goes up), but some of them give an aspect to the verb, such as the prefix meg-, which defines a finite action.

Hungarian word order is often mentioned as free, the truth is that Hungarian word order is more semantical than syntactical. For example because of marking the object using –t, it is not necessary to place the subject before the verb, and the object after it, as in English. This feature makes Hungarian able to focus on particular sections of the sentence – generally, the word before the verb contains the most important information:

|

John lát egy almát. ‘John sees an apple.’ |

John egy almát lát. (or even Egy almát lát John) ‘John an apple sees.’ |

Politeness

Hungarian has a four-tiered system for expressing levels of politeness.

- Ön (önözés): Use of this form in speech shows respect towards the person addressed, but it is also the common way of speaking in official texts and business communications. Here "you", the second person, is grammatically addressed in the third person.

- Maga (magázás, magázódás): Use of this form serves to show that the speaker wishes to distance himself/herself from the person he/she addresses. A boss could also address a subordinate as "maga". Aside from the different pronoun it is grammatically the same as "önözés".

- Néni/bácsi (tetszikezés): Children are supposed to address adults who are not close friends with using "tetszik" ("you like") as a sort of an auxiliary verb with all other verbs. "Hogy vagy?" ("How are you?") here becomes "Hogy tetszik lenni?" ("How do you like to be?"). The elderly are generally addressed this way, even by adults. When using this way of speaking, one will not use normal greetings, but can only say "(kezét) csókolom" ("I kiss (your hand)"). This way of speaking is perceived as somewhat awkward and often creates impossible grammatical structures, but is still widely in use. Another problem created by this form is that when children grow up into their 20s or 30s, they are not sure of how to address family friends that are their parents' age, but whom they have known since they were young. "Tetszik" would make these people feel too old, but "tegeződés" seems too familiar. The best way to avoid this dilemma is to use the "tegeződés" in grammatical structures, but show the respect in the title: "John bácsi, hogy vagy?".

- Te (tegezés, tegeződés or pertu, per tu from latin): Used generally, i.e. with persons with whom none of the above forms of politeness is required. Interestingly, the highest rank, the king was traditionally addressed "per tu" by all, peasants and noblemen alike, though with Hungary not having any crowned king since 1918, this practice survives only in folk tales and children's stories. Use of "tegezés" in the media and advertisements has become more frequent since the early 1990s. It is informal and is normally used in families, among friends, colleagues, among young people, adults speaking to children; can be compared to addressing somebody by their first name in English. Perhaps prompted by the widespread use of English (a language without T-V distinction) on the Internet, "tegezés" is also becoming the standard way to address people over the Internet, regardless of politeness.

The four-tiered system has somewhat been eroded due to the recent expansion of "tegeződés".

Lexicon

| Hungarian | English |

|---|---|

| Derived terms | |

| ad | gives |

| adás | transmission |

| adó | tax or transmitter or transmitting |

| adóhivatal | tax/revenue office |

| adózik | pays tax |

| adózó | taxpayer |

| adós | debtor |

| adósság | debt |

| adalék | additive (ingredient) |

| adag | dose, portion |

| With verbal prefixes | |

| megad | repays (debt); call (poker) |

| eladó | for sale, salesperson |

| hozzáad | augments, adds to |

| As part of compounds | |

| rádióadó | radio station/radio transmitter |

| adomány / from the Latin dominum=dominyum word integration/ |

donation |

| adoma | anecdote |

Giving an exact estimate for the total word count is difficult, since it is hard to define what to call "a word" in agglutinating languages, due to the existence of affixed words and compound words. To have a meaningful definition of compound words, we have to exclude such compounds whose meaning is the mere sum of its elements. The largest dictionaries from Hungarian to another language contain 120,000 words and phrases[9] (but this may include redundant phrases as well, because of translation issues). The new desk lexicon of the Hungarian language contains 75,000 words[9] and the Comprehensive Dictionary of Hungarian Language (to be published in 18 volumes in the next twenty years) will contain 110,000 words.[10] The default Hungarian lexicon is usually estimated to comprise 60,000 to 100,000 words.[11] (Independently of specific languages, speakers actively use at most 10,000 to 20,000 words,[12] with an average intellectual using 25-30 thousand words.[11]) However, all the Hungarian lexemes collected from technical texts, dialects etc. would all together add up to 1,000,000 words.[13]

Hungarian words are built around so-called word-bushes. (See an example on the right.) Thus, words with similar meaning often arise from the same root.

The basic vocabulary shares a couple of hundred word roots with other Uralic languages like Finnish, Estonian, Mansi and Khanty. Examples of such include the verb él 'live' (Finnish elä[14]), the numbers kettő 'two', három 'three', négy 'four' (cf. Mansi китыг kitig, хурум khurum, нила nila, Finnish kaksi, kolme, neljä[14], Estonian kaks, kolm, neli, ), as well as víz 'water', kéz 'hand', vér 'blood', fej 'head' (cf. Finnish[14] and Estonian vesi, käsi, veri, Finnish pää[14], Estonian pea or 'pää).

Except for a few Latin and Greek loan-words, these differences are unnoticed even by native speakers; the words have been entirely adopted into the Hungarian lexicon. There are an increasing number of English loan-words, especially in technical fields.

Another source [16] differs in that loanwords in Hungarian are held to constitute about 45% of bases in the language. Although the lexical percentage of native words in Hungarian is 55%, their use accounts for 88.4% of all words used (the percentage of loanwords used being just 11.6%). Therefore the history of Hungarian has come, especially since the 19th century, to favor neologisms from original bases, whilst still having developed as many terms from neighboring languages in the lexicon.

Word formation

Words can be compound (as in German) and derived (with suffixes).

Compounds

Compounds have been present in the language since the Proto-Uralic era. Numerous ancient compounds transformed to base words during the centuries. Today, compounds play an important role in vocabulary.

A good example is the word arc:

- orr (nose) + száj (mouth) → orca (face) (colloquial until the end of the 19th century and still in use in some dialects) → arc (face)[17]

Compounds are made up of two base words: the first is the prefix, the latter is the suffix. A compound can be subordinative: the prefix is in logical connection with the suffix. If the prefix is the subject of the suffix, the compound is generally classified as a subjective one. There are objective, determinative, and adjunctive compounds as well. Some examples are given below:

- Subjective:

- menny (heaven) + dörög (thunder) → mennydörög (thundering)

- nap (Sun) + sütötte (baked) → napsütötte (sunlit)

- Objective:

- fa (tree, wood) + vágó (cutter) → favágó (lumberjack, literally "woodcutter")

- Determinative:

- új (new) + já (modification of -vá, -vé a suffix meaning "making it to something") + építés (construction) → újjáépítés (reconstruction, literally "making something to be new by construction")

- Adjunctive:

- sárga (yellow) + réz (copper) → sárgaréz (brass)

According to current orthographic rules, a subordinative compound word has to be written as a single word, without spaces; however, if the length of a compound of three or more words (not counting one-syllable verbal prefixes) is seven or more syllables long (not counting case suffixes), a hyphen must be inserted at the appropriate boundary to ease the determination of word boundaries for the reader.

Other compound words are coordinatives: there is no concrete relation between the prefix and the suffix. Subcategories include word duplications (to emphasise the meaning; olykor-olykor 'really occasionally'), twin words (where a base word and a distorted form of it makes up a compound: gizgaz, where the suffix 'gaz' means 'weed' and the prefix giz is the distorted form; the compound itself means 'inconsiderable weed'), and such compounds which have meanings, but neither their prefixes, nor their suffixes make sense (for example, hercehurca 'long-lasting, frusteredly done deed').

A compound also can be made up by multiple (i.e., more than two) base words: in this case, at least one word element, or even both the prefix and the suffix is a compound. Some examples:

- elme [mind; standalone base] + (gyógy [medical] + intézet [institute]) → elmegyógyintézet (asylum)

- (hadi [militarian] + fogoly [prisoner]) + (munka [work] + tábor [camp]) → hadifogoly-munkatábor (work camp of prisoners of war)

Noteworthy lexical items

Points of the compass

Hungarian words for the points of the compass are directly derived from times of day.

- North = észak (from "éj(szaka)", 'night'), as the Sun never shines from the North

- South = dél ('noon'), as the Sun shines from the South at noon

- East = kelet ('rise'), as the Sun rises in the East

- West = nyugat ('set'), as the Sun sets in the West

Hungary is in the Northern Hemisphere, so its vocabulary corresponds to the Sun's appearances there. – The above can be observed with the Latin word meridies, which means 'noon' and 'South' alike.

Two words for "red"

There are two basic words for "red" in Hungarian: "piros" and "vörös" (variant: "veres"; compare with Estonian 'verev' or Finnish 'punainen'). (They are basic in the sense that one is not a sub-type of the other, as the English "scarlet" is of "red".) The word "vörös" is related to "vér", meaning "blood". When they refer to an actual difference in colour (as on a colour chart), "vörös" usually refers to the deeper hue of red. While many languages have multiple names for this colour, Hungarian is special in recognizing two shades of red as separate and distinct "folk colours."[18]

However, the two words are also used independently of the above in collocations. "Piros" is learned by children first, as it is generally used to describe inanimate, artificial things, or things seen as cheerful or neutral, while "vörös" typically refers to animate or natural things (biological, geological, physical and astronomical objects), as well as serious or emotionally charged subjects.

When the rules outlined above are in contradiction, typical collocations usually prevail. In some cases where a typical collocation doesn't exist, the use of either of the two words may be equally adequate.

Examples:

- Expressions where "red" typically translates to "piros": a red road sign, red traffic lights, the red line of Budapest Metro, red (now called express) bus lines in Budapest, a holiday shown in red in the calendar, ruddy complexion, the red nose of a clown, some red flowers (those of a neutral nature, e.g. tulips), red peppers and paprika, red card suits (hearts and diamonds), red stripes on a flag, etc.

- Expressions where "red" typically translates to "vörös": Red Army, red wine, red carpet (for receiving important guests), red hair or beard, red lion (the mythical animal), the Red Cross, the novel The Red and the Black, the Red Sea, redshift, red giant, red blood cells, red oak, some red flowers (those with passionate connotations, e.g. roses), red fox, names of ferric and other red minerals, red copper, rust, red phosphorus, the colour of blushing with anger or shame, the red nose of an alcoholic (in contrast with that of a clown, see above), the red posterior of a baboon, etc.

Kinship terms

Hungarian has separate words for brothers and sisters depending on relative age:

| younger | elder | unspecified relative age | |

| brother | öcs | báty | fivér or fiútestvér |

| sister | húg | nővér | nővér or lánytestvér |

| unspecified gender |

kistestvér | (nagytestvér) | testvér |

(There used to be a separate word for "elder sister", néne, but it has become obsolete [except to mean "aunt" in some dialects] and has been replaced by the generic word for "sister".)

In addition, there are separate prefixes for up to the seventh ancestors and sixth descendants (although there are ambiguities and dialectical differences affecting the prefixes for the fourth (and above) ancestors): Apa (father) -> Nagyapa (grandfather) -> Dédapa (great-grandfather) -> Dédnagyapa (great-great-grandfather) Ükapa (great-great-great-grandfather) Üknagyapa (great-great-great-great-grandfather) -> Szépapa (great-great-great-great-great-grandfather)

| parent | grandparent | great- grandparent |

great-great- grandparent |

great-great-great- grandparent |

| szülő | nagyszülő | dédszülő | ükszülő | szépszülő (OR ük-ükszülő) |

| child | grandchild | great- grandchild |

great-great- grandchild |

great-great-great- grandchild |

| gyer(m)ek | unoka | dédunoka | ükunoka | szépunoka (OR ük-ükunoka) |

Ősszülő or ószülő, as well as óunoka might be used for the great-great-great- great-grandparent or child, respectively.[citation needed]

On the other hand, Hungarian has no specific lexical items for "son" and "daughter", but the words for "boy" and "girl" are applied with possessive suffixes. Nevertheless, the terms are differentiated with different declension or lexemes:

| boy/girl | (his/her) son/daughter |

lover, partner | |

| male | fiú | fia | fiúja/barátja |

| female | lány | lánya | barátnője |

Fia is only used in this, irregular possessive form; it has no nominative on its own. However, the word fiú can also take the regular suffix, in which case the resulting word (fiúja) will refer to a lover or partner (boyfriend), rather than a male offspring.

The word fiú (boy) is also often noted as an extreme example of the ability of the language to add suffixes to a word, by forming fiaiéi, adding vowel-form suffixes only, where the result is quite a frequently used word:

| fiú | boy |

| fia | his/her son |

| fiai | his/her sons |

| fiáé | his/her son's (singular object) |

| fiáéi | his/her son's (plural object) |

| fiaié | his/her sons' (singular object) |

| fiaiéi | his/her sons' (plural object) |

Extremely long words

- megszentségteleníthetetlenségeskedéseitekért

- Partition to root and suffixes with explanations:

| meg- | verb prefix; in this case, it means "completed" |

| szent | holy (the word root) |

| -ség | like English "-ness", as in "holiness" |

| -t(e)len | variant of "-tlen", noun suffix expressing the lack of something; like English "-less", as in "useless" |

| -ít | constitutes a transitive verb from an adjective |

| -het | expresses possibility; somewhat similar to the English auxiliaries "may" or "can" |

| -(e)tlen | another variant of "-tlen" |

| -ség | (see above) |

| ‑es | constitutes an adjective from a noun; like English "-y" as in "witty" |

| -ked | attached to an adjective (e.g. "strong"), produces the verb "to pretend to be (strong)" |

| -és | constitutes a noun from a verb; there are various ways this is done in English, e.g. "-ance" in "acceptance" |

| -eitek | plural possessive suffix, second person plural (e.g. "apple" -> "your apples", where "your" refers to multiple people) |

| -ért | approximately translates to "because of", or in this case simply "for" |

- Translation: "for your [plural] repeated pretending to be undesecratable"

The above word is often considered to be the longest word in Hungarian, although there are longer words like:

- legeslegmegszentségteleníttethetetlenebbjeitekként

- leg|es|leg|meg|szent|ség|telen|ít|tet|het|etlen|ebb|je|i|tek|ként

- "like those of you that are the very least possible to get desecrated"

These words are not used in practice, but when spoken they are easily understood by natives. They were invented to show, in a somewhat facetious way, the ability of the language to form long words. They are not compound words – they are formed by adding a series of one and two-syllable suffixes (and a few prefixes) to a simple root ("szent", saint). There is virtually no limit for the length of words, but when too many suffixes are added, the meaning of the word becomes less clear, and the word becomes hard to understand, and will work like a riddle even for native speakers.

Writing system

It reads "feheruuaru rea meneh hodu utu rea" (in modern Hungarian "Fehérvárra menő hadi útra", meaning "to the military road going to Fehérvár)

The Hungarian language was originally written in Old Hungarian script, a script reminiscent of runic writing systems. When Stephen I of Hungary established the Kingdom of Hungary in the year 1000, the old system was gradually discarded in favour of the Latin alphabet. Although now not used at all in everyday life, the old script is still known and practiced by some enthusiasts.

Modern Hungarian is written using an expanded Latin alphabet, and has a phonemic orthography, i.e. pronunciation can generally be predicted from the written language. In addition to the standard letters of the Latin alphabet, Hungarian uses several modified Latin characters to represent the additional vowel sounds of the language. These include letters with acute accents (á,é,í,ó,ú) to represent long vowels, and umlauts (ö and ü) and their long counterparts ő and ű to represent front vowels. Sometimes (usually as a result of a technical glitch on a computer) ô or õ is used for ő and û for ű. This is often due to the limitations of the Latin-1 / ISO-8859-1 code page. These letters are not part of the Hungarian language, and are considered misprints. Hungarian can be properly represented with the Latin-2 / ISO-8859-2 code page, but this code page is not always available. (Hungarian is the only language using both ő and ű.) Unicode includes them, and so they can be used on the Internet.

Additionally, the letter pairs <ny>, <ty>, and <gy> represent the palatal consonants /ɲ/, /c/, and /ɟ/ (a little like the "d+y" sounds in British "duke" or American "would you") - a bit like saying "d" with your tongue pointing to your upper palate.

Hungarian uses <s> for /ʃ/ and <sz> for /s/, which is the reverse of Polish usage. The letter <zs> is /ʒ/ and <cs> is /t͡ʃ/. These digraphs are considered single letters in the alphabet. The letter <ly> is also a "single letter digraph", but is pronounced like /j/ (English <y>), and appears mostly in old words. The letters <dz> and <dzs> /d͡ʒ/ are exotic remnants and are hard to find even in longer texts. Some examples still in common use are madzag ("string"), edzeni ("to train (athletically)") and dzsungel ("jungle").

Sometimes additional information is required for partitioning words with digraphs: házszám ("street number") = ház ("house") + szám ("number"), not an unintelligible házs + zám.

Hungarian distinguishes between long and short vowels, with long vowels written with acutes. It also distinguishes between long and short consonants, with long consonants being doubled. For example, lenni ("to be"), hozzászólás ("comment"). The digraphs, when doubled, become trigraphs: <sz>+<sz>=<ssz>, e.g. művésszel ("with an artist"). But when the digraph occurs at the end of a line, all of the letters are written out. For example ("with a bus"):

- ... busz-

- szal...

When the first lexeme of a compound ends in a digraph and the second lexeme starts with the same digraph, both digraphs are written out: lány + nyak = lánynyak ("girl's neck").

Usually a trigraph is a double digraph, but there are a few exceptions: tizennyolc ("eighteen") is a concatenation of tizen + nyolc. There are doubling minimal pairs: tol ("push") vs. toll ("feather" or "pen").

While to English speakers they may seem unusual at first, once the new orthography and pronunciation are learned, written Hungarian is almost completely phonemic.

Order of words

Basic rule is that the order is from general to specific. This is a typical analytical approach and is used generally in Hungarian.

Name order

The Hungarian language uses the so-called eastern name order, in which the family name (general, deriving from the family) comes first and the given name (specific, relates to the person) comes last. A second given name is also often present, which follows the first given name. This is comparable to the Anglo-Saxon custom of middle names.

Hungarian names in foreign languages

For clarity, in foreign languages Hungarian names are usually represented in the western name order. Sometimes, however, especially in the neighboring countries of Hungary – where there is a significant Hungarian population – the Hungarian name order is retained as it causes less confusion there.

For an example of foreign use, the birth name of the Hungarian-born physicist, the "father of the hydrogen bomb" was Teller Ede, but he became known internationally as Edward Teller. Prior to the mid-20th century, given names were usually translated along with the name order; this is no longer as common. For example, the pianist uses András Schiff when abroad, not Andrew Schiff (in Hungarian Schiff András). A second given name, if present, becomes a middle name, but is usually written out in full, and not truncated to an initial.

Foreign names in Hungarian

In modern usage, foreign names retain their order when used in Hungarian. Therefore:

- Amikor Kiss János Los Angelesben volt, látta John Travoltát.

- The Hungarian name Kiss János is in the Hungarian name order (János means John), but the foreign name John Travolta remains in the western name order.

Before the 20th century, not only was it common to reverse the order of foreign personalities, they were also "Hungarianized": Goethe János Farkas (originally Johann Wolfgang Goethe). This usage sounds odd today, when only a few well-known personalities are referred to using their Hungarianized names, including Verne Gyula (Jules Verne), Marx Károly (Karl Marx), Kolumbusz Kristóf (Christopher Columbus, note that it is also translated in English).

Some native speakers disapprove of this usage; the names of certain religious personalities (including popes), however, are always Hungarianized by practically all speakers, such as Luther Márton (Martin Luther), Husz János (Jan Hus), Kálvin János (John Calvin); just like the names of monarchs, for example the king of Spain, Juan Carlos I is referred to as I. János Károly or the queen of the UK, Elizabeth II is referred to as II. Erzsébet.

Date and time

The Hungarian convention on date and time is:

- 2004. január 5. 16:32

The order is big endian (going from generic to specific): 1. year, 2. month, 3. day, 4. hour, 5. minute.

Addresses

Although address formatting is increasingly being influenced by Indo-European conventions, traditional Hungarian style is:

1052 Budapest, Deák tér 1.

So the order is 1. postcode, 2., city (most general) 3., street (more specific) 4., house number (most specific)

Vocabulary examples

Note: The stress is always placed on the first syllable of each word. The remaining syllables all receive an equal, lesser stress. All syllables are pronounced clearly and evenly, even at the end of a sentence, unlike in English.

- Hungarian (person, language): magyar [mɒɟɒr]

- Hello!:

- Formal, when addressing a stranger: "Good day!": Jó napot (kívánok)! [joːnɒpot kivaːnok].

- Informal, when addressing someone you know very well: Szia! [siɒ] (it sounds almost exactly like American colloquialism "See ya!" with a shorter "ee".)

- Good-bye!: Viszontlátásra! (formal) (see above), Viszlát! [vislaːt] (semi-informal), Szia! (informal: same stylistic remark as for "Hello!" )

- Excuse me: Elnézést! [ɛlneːzeːʃt]

- Please:

- Kérem (szépen) [keːrɛm seːpɛn] (This literally means "I'm asking (it/you) nicely", as in German Danke schön, "I thank (you) nicely". See next for a more common form of the polite request.)

- Legyen szíves! [lɛɟɛn sivɛʃ] (literally: "Be (so) kind!")

- I would like ____, please: Szeretnék ____ [sɛrɛtneːk] (this example illustrates the use of the conditional tense, as a common form of a polite request; it literally means "I would like".)

- Sorry!: Bocsánat! [botʃaːnɒt]

- Thank you: Köszönöm [køsønøm]

- that/this: az [ɒz], ez [ɛz]

- How much?: Mennyi? [mɛɲːi]

- How much does it cost?: Mennyibe kerül? [mɛɲːibɛ kɛryl]

- Yes: Igen [iɡɛn]

- No: Nem [nɛm]

- I don't understand: Nem értem [nɛm eːrtɛm]

- I don't know: Nem tudom [nɛm tudom]

- Where's the toilet?:

- Hol van a vécé? [hol vɒn ɒ veːtseː] (vécé/veːtseː is the Hungarian pronouncation of the English abbreviation of "Water Closet")

- Hol van a mosdó? [hol vɒn ɒ moʒdoː] – more polite (and word-for-word) version

- generic toast: Egészségünkre! [ɛɡeːʃːeːɡynkrɛ] (literally: "To our health!")

- juice: gyümölcslé [ɟymøltʃleː]

- water: víz [viːz]

- wine: bor [bor]

- beer: sör [ʃør]

- tea: tea [tɛjɒ]

- milk: tej [tɛj]

- Do you speak English?: Tud(sz) angolul? [tud / tuts ɒnɡolul] Note that the fact of asking is only shown by the proper intonation: continually rising until the penultimate syllable, then falling for the last one.

- I love you: Szeretlek [sɛrɛtlɛk]

- Help!: Segítség! [ʃɛɡiːtʃeːɡ]

- It is needed: kell

- I need to go: Mennem kell

Controversy over origins

Mainstream linguistics holds that Hungarian is part of the Uralic family of languages, related ultimately to languages such as Finnish and Estonian, although it would be particularly close to Khanty and Mansi languages located near the Ural Mountains.

- For many years (from 1869), it was a matter of dispute whether Hungarian was a Finno-Ugric/Uralic language, or was more closely related to the Turkic languages, a controversy known as the "Ugric-Turkish war", or whether indeed both the Uralic and the Turkic families formed part of a superfamily of "Ural-Altaic languages". Hungarians did absorb some Turkic influences during several centuries of co-habitation. For example, it appears that the Hungarians learned animal breeding techniques from the Turkic Chuvash, as a high proportion of words specific to agriculture and livestock are of Chuvash origin. There was also a strong Chuvash influence in burial customs. Furthermore, all Ugric languages, not just Hungarian, have Turkic loanwords related to horse riding. Nonetheless, the science of linguistics shows that the basic wordstock and morphological patterns of the Hungarian language are solidly based on a Uralic heritage.[citation needed]

- A theory also well-known (still in dispute) is that the Hungarian language is a descendant of the Sumerian. Some linguists and historians (like Ida Bobula, Ferenc Badiny Jós, dr Tibor Baráth and others) had been working hard for decades and had published many detailed works[19], and, purportedly, also there are some significant archaeological findings in this matter (like the Tartaria tablets). However mainstream linguists reject the Sumerian theory as pseudoscience.

- Hungarian has often been claimed to be related to Hunnish, since Hungarian legends and histories show close ties between the two peoples; also, the name Hunor is preserved in legends and (along with a few Hunnic-origin names, such as Attila) is still used as a given name in Hungary. Many people share the belief that the Székelys, a Hungarian ethnic group living in Romania, are descended from the Huns. However, the link with Hunnish has no linguistic foundation since most scientists consider the Hunnic language as being part of the Turkic language family.

There have been attempts, dismissed by mainstream linguists, to show that Hungarian is related to other languages including Hebrew, Egyptian, Etruscan, Basque, Persian, Pelasgian, Greek, Chinese, Sanskrit, English, Tibetan, Magar, Quechua, Armenian and at least 42 other Asian, European and even American languages.[20]

Comparison of some Finno-Ugric words

Wiktionary: Swadesh lists for Finno-Ugric languages

| Hungarian | Estonian | Mordvinic (Erzya dialect) | Komi-Permyak | English meaning |

# by the Swadesh-list |

Finnish |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| én (if not written, is indicated by the -*m suffix) |

mina | мон mon | ме me | I, myself, me | 1 | minä |

| te | sina | тон ton | тэ te | you/thou | 2 | sinä |

| mi | meie, me | минь miń | ми mi | we | 4 | me |

| ti | teie, te | тынь tyń | ти ti | you (plural) | 5 | te |

| ez/itt | see | те te | тайö tajö | this/here | 7 | tämä/täällä |

| az/ott | too | што što | сійö sijö | that/there | 8 | tuo/tuolla |

| ki? | kes? | кие? kije? | коді? kodi? | who? | 11 | kuka? |

| mi? | mis? | мезе? meze? | мый? myj? | what? | 12 | mikä? |

| egy | üks | вейке vejke | öтік ötik | one | 22 | yksi |

| kettő | kaks | кавто kavto | кык kyk | two | 23 | kaksi |

| három | kolm | колмо kolmo | куим kuim | three | 24 | kolme |

| négy | neli | ниле nile | нёль ńol | four | 25 | neljä |

| öt | viis | вете vete | вит vit | five | 26 | viisi |

| nej | naine | ни ni | гöтыр götyr | wife | 40 | vaimo |

| anya | ema | (тиринь) ава (tiriń) ava | мам mam | mother | 42 | äiti |

| fa | puu | чувто čuvto | пу pu | tree, wood | 51 | puu |

| vér | veri | верь veŕ | вир vir | blood | 64 | veri |

| haj | juuksed | черь čeŕ | юрси jursi | hair | 71 | hius, hiukset |

| fej | pea | пря pŕa | юр jur | head | 72 | pää |

| fül | kõrv | пиле pile | пель peĺ | ear | 73 | korva |

| szem | silm | сельме seĺme | син sin | eye | 74 | silmä |

| orr | nina | судо sudo | ныр nyr | nose | 75 | nenä |

| száj | suu | курго kurgo | вом vom | mouth | 76 | suu |

| fog | hammas | пей pej | пинь piń | tooth | 77 | hammas |

| láb | jalg | пильге piĺge | кок kok | foot | 80 | jalka |

| kéz | käsi | кедь ked́ | ки ki | hand | 83 | käsi |

| szív/szűny | süda | седей sedej | сьöлöм śölöm | heart | 90 | sydän |

| inni | jooma | симемс simems | юны juny | to drink | 92 | juoda |

| tudni | teadma | содамс sodams | тöдны tödny | to know | 103 | tietää |

| élni | elama | эрямс eŕams | овны ovny | to live | 108 | elää |

| víz | vesi | ведь ved́ | ва va | water | 150 | vesi |

| kő | kivi | кев kev | из iz | stone | 156 | kivi |

| ég/menny | taevas | менель meneĺ | енэж jenezh | sky/heaven | 162 | taivas |

| szél | tuul | варма varma | тöв töv | wind | 163 | tuuli |

| tűz | tuli | тол tol | би bi | fire | 167 | tuli |

| éj | öö | ве ve | вой voj | night | 177 | yö |

See also

- History of the Hungarian language

- Hungarian Cultural Institute

- List of English words of Hungarian origin

- Magyar szótár - A Dictionary of the Hungarian Language (a book review)

Bibliography

Courses

- Colloquial Hungarian - The complete course for beginners. Rounds, Carol H.; Sólyom, Erika (2002). London; New York: Routledge. ISBN 0-415-242584.

- This book gives an introduction to the Hungarian language in 15 chapters. The dialogues are available on cassette or CDs.

- Teach Yourself Hungarian - A complete course for beginners. Pontifex, Zsuzsa (1993). London: Hodder & Stoughton. Chicago: NTC/Contemporary Publishing. ISBN 0-340-56286-2.

- This is a complete course in spoken and written Hungarian. The course consists of 21 chapters with dialogues, culture notes, grammar and exercises. The dialogues are available on cassette.

- Hungarolingua 1 - Magyar nyelvkönyv. Hoffmann, István; et al. (1996). Debreceni Nyári Egyetem. ISBN 963-472-083-8

- Hungarolingua 2 - Magyar nyelvkönyv. Hlavacska, Edit; et al. (2001). Debreceni Nyári Egyetem. ISBN 963-036-698-3

- Hungarolingua 3 - Magyar nyelvkönyv. Hlavacska, Edit; et al. (1999). Debreceni Nyári Egyetem. ISBN 963-472-083-8

- These course books were developed by the University of Debrecen Summer School program for teaching Hungarian to foreigners. The books are written completely in Hungarian. There is an accompanying 'dictionary' for each book with translations of the Hungarian vocabulary in English, German, and French.

- "NTC's Hungarian and English Dictionary" by Magay and Kiss. ISBN 0-8442-4968-8 (You may be able to find a newer edition also. This one is 1996.)

Grammars

- A practical Hungarian grammar (3rd, rev. ed.). Keresztes, László (1999). Debrecen: Debreceni Nyári Egyetem. ISBN 963-472-300-4.

- Practical Hungarian grammar: [a compact guide to the basics of Hungarian grammar]. Törkenczy, Miklós (2002). Budapest: Corvina. ISBN 963-13-5131-9.

- Hungarian verbs and essentials of grammar: a practical guide to the mastery of Hungarian (2nd ed.). Törkenczy, Miklós (1999). Budapest: Corvina; Lincolnwood, [Ill.]: Passport Books. ISBN 963-13-4778-8.

- Hungarian: an essential grammar. Rounds, Carol (2001). London; New York: Routledge. ISBN 0-415-22612-0.

- Hungarian: Descriptive grammar. Kenesei, István, Robert M. Vago, and Anna Fenyvesi (1998). London; New York: Routledge. ISBN 0-415-02139-1.

- Hungarian Language Learning References (including the short reviews of three of the above books)

- Noun Declension Tables - HUNGARIAN. Budapest: Pons. Klett. ISBN 9789639641044

- Verb Conjugation Tables - HUNGARIAN. Budapest: Pons. Klett. ISBN 9789639641037

References

- ^ Lebedynsky, Iaroslav. Les Nomades: Les peuples nomades de la steppe des origines aux invasions mongoles. p. 191

- ^ Sugar, P.F..A History of Hungary. University Press, 1996: p. 9

- ^ Maxwell, A.Magyarization, Language Planning and Whorf: The word Uhor as a Case Study in Linguistic RelativismMultilingua 23: 319, 2004.

- ^ Marcantonio, Angela. The Uralic Language Family: Facts, Myths and Statistics. Blackwell Publishing, 2002: p. 19

- ^ Laszlo Gyula, The Magyars: Their Life and Civilization, (1996) pg. 37

- ^ "Hungary - Early history". Library of Congress (public domain). Retrieved 2008-06-29.

- ^ Marius Sala. Vocabularul reprezentativ al limbilor romanice, Editura Ştiinţifică şi Enciclopedică, Bucureşti, 1988

- ^ Szende (1994:91)

- ^ a b A nyelv és a nyelvek ("Language and languages"), edited by István Kenesei. Akadémiai Kiadó, Budapest, 2004, ISBN 963-05-7959-6, p. 77)

- ^ The first two volumes of the 20-volume series were introduced on 13 November, 2006, at the Hungarian Academy of Sciences (in Hungarian)

- ^ a b "Hungarian is not difficult" (interview with Ádám Nádasdy)

- ^ A nyelv és a nyelvek ("Language and languages"), edited by István Kenesei. Akadémiai Kiadó, Budapest, 2004, ISBN 963-05-7959-6, p. 86)

- ^ A nyelv és a nyelvek ("Language and languages"), edited by István Kenesei. Akadémiai Kiadó, Budapest, 2004, ISBN 963-05-7959-6, pp. 76 and 86)

- ^ a b c d ""Related words" in Finnish and Hungarian". Helsinki University Bulletin. Retrieved 2008-06-15.

- ^ A nyelv és a nyelvek ("Language and languages"), edited by István Kenesei. Akadémiai Kiadó, Budapest, 2004, ISBN 963-05-7959-6, p. 134)

- ^ The Structure and Development of the Finnish Language, The Uralic and Altaic Series: 1960-1993 V.1-150, By Denis Sinor, John R. Krueger, Lauri Hakulinen, Gustav Bayerle, Translated by John R. Krueger, Compiled by Gustav Bayerle, Contributor Denis Sinor, Published by Routledge, 1997 ISBN 0700703802, 9780700703807, 383 pages. p. 307

- ^ "It's written in chapter Testrészek". Nemzetismeret.hu. Retrieved 2010-01-31.

- ^ Berlin, B and Kay, P (1969). "Basic Color Terms." Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press

- ^ "Myths - The Hungarian Identity". Imninalu.net. Retrieved 2010-01-31. http://www.acronet.net/~magyar/english/96-07/baraeast.html

- ^ Zsirai Miklós: Őstörténeti csodabogarak. Budapest, 1943.

External links

- Hungarian - A Strange Cake on the Menu - article by Nádasdy Ádám

- Ethnologue report for Hungarian

- Introduction to Hungarian

- Hungarian Profile

- List of formative suffixes in Hungarian

- The relationship between the Finnish and the Hungarian languages

- Hungarian Language Review at How-to-learn-any-language.com

- "The Hungarian Language: A Short Descriptive Grammar" by Beáta Megyesi (PDF document)

- The old site of the Indiana University Institute of Hungarian Studies (various resources)

- Hungarian Language Learning References on the Hungarian Language Page (short reviews of useful books)

- One of the oldest Hungarian texts - A Halotti Beszéd (The Funeral Oration)

- Live stream of Hungarian news radio station InfoRádió - example of Hungarian speech

- Hungarian Reference (a grammatical guide)

- A short English-Hungarian-Japanese phraselist(renewal) incl.sound file

- free-dictionary-translation - English <-> Hungarian, African, Chinese, Dutch, French, Gealic, German, Greek, Indonesian, Italian, Japanese, Korean, Latin, Portuguese, Polish, Russian, Swedish, Spanish, Czech, Turkish, Vietnamese

- Wikihu (a wiki on Hungarian grammar, in french)

- WikiLang - Hungarian Page (Hungarian grammar / lessons, in English)

Encyclopaedia Humana Hungarica

- Introduction to the History of the Language; The Pre-Hungarian Period; The Early Hungarian Period; The Old Hungarian Period

- The Linguistic Records of the Early Old Hungarian Period; The Linguistic System of the Age

- The Old Hungarian Period; The System of the Language of the Old Hungarian Period

- The Late Old Hungarian Period; The System of the Language

- The First Half of the Middle Hungarian Period; Turkish Loan Words

Dictionaries

- Hungarian Dictionary: from Webster's Dictionary

- Hungarian ↔ English created by the Hungarian Academy of Sciences - Computer and Automation Research Institute MTA SZTAKI (also includes dictionaries for the following languages to and from Hungarian : German, French, Italian, Dutch, and Polish)

- English-Hungarian-Finnish - three language freely editable online dictionary

- Collection of Hungarian Technical Dictionaries

- Hungarian-English False friends (False friend)

- Hungarian slang

- Hungarian bilingual dictionaries

Online translators

- Free English->Hungarian translation service - does not translate texts longer than 500 characters

- Free Dictionary Translation - English - Hungary altogether 136056 entries.

Online language courses

- Online Hungarian Language Courses

- A Hungarian Language Course by Aaron Rubin

- Online course hungarotips.com

- Study Hungarian! (AFS.com)

- Hungarian Phrase Guides

- Magyaróra: New paths to the Hungarian language

- Hungarian Language Lessons - Puzzles, Quizzes, Sound Files

- We learn Hungarian - wiki based learning group

- Articles with specifically marked weasel-worded phrases from September 2009

- Hungarian language

- Agglutinative languages

- Languages of Austria

- Languages of Croatia

- Languages of Hungary

- Languages of Romania

- Languages of Slovakia

- Languages of Slovenia

- Languages of Serbia

- Languages of Vojvodina

- Vowel harmony languages